Abstract

The ordering and relative energy splitting between bright and dark excitons are critical to the optical properties of single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs), as they eventually determine the radiative and non-radiative recombination processes of generated carriers. In this work, we report systematic high-field magneto-optical study on the relative ordering between bright and dark excitons in SWNTs. We identified the relative energy position of the dark exciton unambiguously by brightening it in ultra-high magnetic field. The bright-dark excitonic ordering was found to depend not only on the tube structure, but also on the type of transitions. For the 1st sub-band transition, the bright exciton appears to be higher in energy than its dark counterpart for any chiral species and is robust against environmental effect. While for the 2nd sub-band, their relative ordering was found to be chirality-sensitive: the bright exciton can be either higher or lower than the dark one, depending on the specific nanotube structures. These findings provide new clues for engineering the optical and electronic properties of SWNTs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

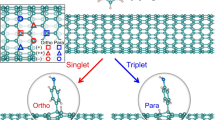

Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) are attracting lots of attention in recent years due to their potential applications in a variety of fields1,2,3,4. Because of valley degeneracy and electron spins, SWNTs have very complicated excitonic structures that comprise a total of 16 excitonic states, among which only one state is optically bright and all others are dark5,6,7. The ordering and relative energy splitting between these excitonic states, especially the ordering between bright and dark excitons, are critical to the optical properties of SWNTs, as they essentially determine the relaxation processes and thus the fate of optically or electrically generated carriers. The energy positions of the dark states were generally believed to be lower than that of the bright one, based on the fact that the photoluminescence quantum yield of SWNTs is extremely low (10−4–10−3)1,8,9,10,11,12. However, recent theoretical studies show that this is not always the case. Calculations by Ando et. al. reveal that the ordering between SWNT excitonic states depends sensitively on the ratio of the intra- and inter-valley short-range Coulomb interactions5. As one of the most important issues for the optical properties of SWNTs, it is fundamentally interesting as well as practically important, to clarify the relative ordering between bright and dark excitonic states.

In this work, we report high-field magneto-optical study on the relative ordering between bright and dark excitons in SWNTs for both 1st (E11) and 2nd (E22) sub-band transitions. Considering the fact that electronic properties of SWNTs usually show family patterns, we selected the (6,4) SWNTs as a representative for the Type I species ((2n + m) mod 3 = 1) and (6,5) for the Type II species ((2n + m) mod 3 = 2) in our study. They were isolated from a HiPco mixture using the gel chromatography method and essentially contain only one specific chirality13,14. For the alignment of the nanotubes, we used a simple but efficient film-stretching technique with a home-made automatic stretching machine15. From the anisotropic absorption measurements, the average angle θ between SWNT axis and the stretched direction of the SWNTs/PVA film was estimated to be ~30° and ~29° for the (6,4) and (6,5) species, respectively. All the processes for the (6,4) and (6,5) species were done completely in the same way, to exclude any possible environmental effect on the ordering between bright and dark excitons. The experimental method we used to identify the relative energy position of the dark exciton is to brighten it using ultra-high magnetic fields. The pulsed high magnetic field up to 190 T was generated by the single-turn coil technique16. All measurements were performed at room temperature under the Voigt geometry.

Results

The full absorption spectra of the purified (6,4) and (6,5) SWNTs dispersed in sodium dodecyl sulfate solutions were shown in Fig. 1. A series of well-defined absorption peaks can be identified from the spectra for both samples. Comparing with theoretical calculations and existing literatures, we were able to assign almost all the peaks to the (6,4) and (6,5) species, implying high quality of the samples. For the (6,5) sample, absorption from other species is negligible. As a contrast, for the (6,4) sample, the (6,5) SWNTs exist as a minor species.

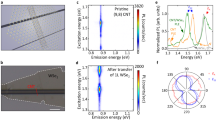

Fig. 2(a) shows the typical high-field magneto-absorption spectra for the E11 transition of the stretch-aligned (6,4) SWNTs. A single peak, corresponding to the E11 bright exciton of the (6,4) SWNTs, can be clearly observed at zero field. As an external magnetic field was applied, obvious peak splitting appears and finally results in two independent peaks with comparable intensities for magnetic fields higher than 110 T. However, when examined carefully, it could be clearly identified that the splitting is due to the emergence of a new peak on the long wavelength (i.e., low energy) side of the bright exciton peak, as shown by the dashed guidelines.

Typical absorption spectra of the (6,4) SWNTs in high magnetic fields.

(a) E11 transition; (b) E22 transition. D: stretched direction of the SWNTs/PVA film. Green dashed lines in (b): Voigt fittings for the spectrum at 172 T. The dashed arrows are guidelines showing the relative energy positions of the bright and dark excitons. The spectra of E22 have been smoothed using the “Adjacent Averaging” procedure to make the spectral evolutions more clearly visible.

Typical high-field magneto-absorption spectra for the E22 transition of the (6,4) SWNTs, where absorption from the minor (6,5) species has been subtracted (FIG. S5, S7, Supporting Information), are shown in Fig. 2(b). While a single peak corresponding to the E22 bright exciton is observed at zero field, obvious peak broadening can be found when an external magnetic field was applied. For magnetic field higher than 160 T, the absorption spectra can be clearly identified to be composed of two peaks, showing the splitting of the absorption spectra in high magnetic field. This peak splitting can be more clearly demonstrated by the Voigt fitting of the spectra, as shown by the green dashed lines in Fig. 2(b). Following the evolution of the absorption spectra in high magnetic fields, it can be clearly identified that the splitting is also due to the emergence of a new peak on the long wavelength side of the bright exciton peak, the same as its E11 counterpart.

Discussion

The evolutions of the aborption spectra in high magnetic fields can be well understood from the unique Aharonov-Bohm (AB) effect of SWNTs5,6,17,18,19,20. Upon the application of an external magnetic field along the tube axis, the magnetic flux threading the tubes mixes the wave functions of the bright and dark excitons with zero angular momentum and redistributes the oscillator spectral weight between the two excitons, leading to the brightening of the dark excitonic state. Therefore, it is clear that the emergence of a new peak in the magneto-absorption spectra, as shown in Fig. 2(a) and (b), is due to the brightening of the dark exciton in high magnetic fields. The location of the new peak, which is on the low energy side of the bright exciton peak, is a direct demonstration that the dark exciton lies below the bright exciton for both E11 and E22 transitions of the (6,4) SWNTs.

However, what is interesting is that, the (6,5) SWNTs which were prepared completely in the same way, were found to exhibit drastically different characteristics in high magnetic fields. Our high-field magneto-absorption measurements up to 190 T, as analyzed in detail in Ref. 21, reveal that the relative ordering between bright and dark excitons is inverse for the 1st and 2nd sub-band transitions for the (6,5) SWNTs: while the dark exciton lies ~8.5 meV below the bright exciton in the 1st sub-band transition, the dark exciton in the 2nd sub-band transition was found to be ~9.0 meV higher in energy than the bright excitonic state21. Compared with the results of the (6,4) SWNTs, one could find that the dark exciton can be either higher or lower than the bright one in the E22 transitions. This means, surprisingly, that the relative ordering between bright and dark excitons is chirality-sensitive in the E22 transitions.

Besides the peak splitting in high magnetic fields, the relative ordering between bright and dark excitons can be further confirmed from the magnetic field dependent oscillator strength of the respective excitonic states. The field-dependent oscillator strength of the bright and dark excitons, which were extracted from the Voigt fitting of the magneto-absorption spectra, are shown in Fig. 3(a) and (b) for E11 and E22 transitions, respectively. Results for the (6,4) and (6,5) SWNTs are shown in the same figure for an explicit comparison. While the magnetic field dependent oscillator strength of the E11 transitions (Fig. 3(a)) show rather similar behaviors for both (6,4) and (6,5) SWNTs, significant differences can be found in the case of the E22 transitions for the two species. As shown in Fig. 3(b), for E22 of the (6,5) SWNTs (symbol: “triangle”), the gap between the intensities of the bright and dark excitonic components becomes smallest at ~125 T and then becomes larger and larger again in higher fields. However, for E22 of the (6,4) SWNTs (symbol: “circle”), intensities of the bright and dark excitons tend to converge in sufficiently high magnetic fields, in strong contrast to the case of the (6,5) SWNTs. The converging point is estimated to be at ~205 T, as shown by the thin dashed line in Fig. 3(b).

Intensity evolutions and theoretical predictions.

(a–b) Intensities of the bright and dark excitons as a function of magnetic field for (6,4) (circle) and (6,5) (triangle) SWNTs, respectively. (a) E11 transition; (b) E22 transition. (c–d) Schematic diagram for the intensity evolutions of bright and dark excitons in magnetic fields in two cases: (c) dark exciton is lower in energy than the bright exciton; (d) dark exciton is higher in energy than the bright exciton. Dashed lines in (a)–(b) are fitting curves.

The significant differences in the magnetic field dependent oscillator strength for the E22 transitions of the (6,4) and (6,5) SWNTs stem from their differences in the relative ordering between bright and dark excitons. According to the mechanism of the AB effect for SWNTs, the dark exciton gains oscillator strength gradually at the expense of the bright exciton, upon the application of an external magnetic field5. In the case that the dark exciton lies below the bright exciton, the dark state is shifted to lower energy while the bright state moves in the higher-energy direction. Thus, the dark exciton, which is brightened by the external magnetic field, will eventually have larger oscillator strength than the bright exciton, since its energy decreases with magnetic field. In the other case when the dark exciton is higher in energy than the bright one, the dark state would move towards higher energy while the bright state goes in the lower-energy direction. The oscillator strength of the dark exciton increases gradually at the beginning, due to the magnetic field brightening. However, for magnetic field higher than some critical value, the oscillator strength of the dark exciton decreases again, since its energy position becomes higher and higher in magnetic fields. A schematic diagram for these two cases, similar to that in Ref. 21, was shown in Fig. 3(c) and (d), for the readers' convenience. Compared with the experimental data shown in Fig. 3(b), it can be seen clearly, that the intensity evolutions of the E22 transitions for the (6,4) and (6,5) SWNTs mimic those shown in Fig. 3(c) and Fig. 3(d), respectively. This confirms again, that the dark exciton lies below the bright exciton in the E22 transition for the (6,4) SWNTs, while for the (6,5) SWNTs the dark exciton is higher in energy than the bright one in the E22 transition. Moreover, it is obvious from Fig. 3(a) that the intensities of the bright and dark excitons in the E11 transitions tend to converge in high magnetic fields for both (6,4) and (6,5) SWNTs, following that shown in Fig. 3(c). This justifies again, that the dark exciton is lower than the bright exciton in the E11 transition for both (6,4) and (6,5) species.

In addition to the ordering between bright and dark excitons, we may further deduce the parameters for the AB effect of SWNTs from the Voigt fitting of the magneto-absorption spectra. The peak shifts of the bright and dark excitons are shown in Fig. 4(a) and (b) for E11 and E22 transitions, respectively, for both (6,4) and (6,5) SWNTs. Evolutions of the bright and dark excitonic components in magnetic fields were further fitted using the empirical formulae12,22:

where Eg = (Eb + Ed)/2 denotes the central energy of the bright and dark excitons in the absence of magnetic field, Δbd represents the zero-field splitting and ΔAB = μ B cosθ is the so-called AB splitting. The parameters Δbd and μ were determined so as to fit the field-dependent data of both peak energy and peak intensity well. The best-fit curves are shown by the dashed lines in Fig. 3(a–b) and Fig. 4(a–b). For E11 transition, fitting using the above formulae gives Δbd ≈ 9.1 meV and μ ≈ 0.55 meV/T for the (6,4) SWNTs and Δbd ≈ 8.5 meV, μ ≈ 0.57 meV/T for the (6,5) SWNTs21. For E22 transition, the fitting parameters are: Δbd ≈ 10.9 meV and μ ≈ 0.54 meV/T for (6,4) and Δbd ≈ −9.0 meV and μ ≈ 0.65 meV/T for (6,5) SWNTs. The chirality dependence of the bright-dark excitonic splitting Δbd and the AB splitting coefficient μ have been a subject of wide interest in the past few years. Relevant studies show that the zero-field splitting Δbd decreases with tube diameter while the coefficient μ increases9,23,24,25. Compared with our experimental data for the (6,4) and (6,5) SWNTs, it is promising to find that Δbd does decrease while μ increases with the tube diameter for both E11 and E22 transitions, in qualitative agreement with existing results.

Energies of the bright (open symbol) and dark (filled symbol) excitons as a function of magnetic field for the (6,4) (circle) and (6,5) (triangle) SWNTs, respectively.

(a) E11 transition; (b) E22 transition. The energies are plotted with respect to Eg which denotes the central energy of the bright and dark excitons at zero field. Dashed lines are fitting curves.

While the relative ordering between bright and dark excitons has been confirmed to be chirality sensitive for the E22 transition, now we turn our attention to the case of the E11 transition. Although the dark exciton was found to be lower in energy than the bright one in the E11 transition for both (6,4) and (6,5) SWNTs, we cannot give a definite conclusion yet based only on these two species. However, our earlier high-field magneto-optical study on the PFO-ACCVD SWNTs showed, that the dark exciton also lies below the bright exciton in the E11 transition for the (7,5) and (7,6) SWNTs26. Besides, unlike the E22 transition which is only detectable by absorption measurements, the E11 transition can be experimentally accessed much more easily by a number of techniques, such as PL, PLE and absorption measurement. Moreover, due to the relatively small linewidth, the minimum magnetic field required for a clear AB splitting in the E11 transition can be much lower than that for the E22 transition. The relative energy positions of the bright and dark excitons in the E11 transition have been revealed for a wide variety of SWNT species in recent years, due to their experimental feasibility9,12,19,26,27. Some representative results are summarized in Table I. Interestingly, it is found that the dark exciton is lower than the bright one in the E11 transition for all these species. Further, it is worth pointing out that although the E11 transition has been studied for various chiralities for many years, no exception for the relative ordering between bright and dark excitons has ever been found. These data, together with our results, leads us to the conclusive suggestion, that the dark exciton is lower in energy than the bright exciton in the E11 transition for any chiral SWNTs. Moreover, although SWNTs ever studied were embedded or dissolved using various substances (e.g., PVA, gelatin, D2O and PFO)9,12,19,26,27, the relative ordering between bright and dark excitons in the E11 transition turned out to be the same. This strongly implies that the relative ordering between bright and dark excitons is robust against environmental effect for the E11 transition.

Now we have clarified that the 1st and 2nd sub-band transitions exhibit completely different characteristics for the relative ordering between bright and dark excitons. This phenomenon can be roughly rationalized from Ando's calculation5. In Ando's theory, the excitonic ordering depends on two intrinsic parameters w1 and w2, which represent the short-range intra- and inter-valley Coulomb interactions, respectively. The bright exciton can be either higher or lower than its dark counterpart, i.e., Δbd = Ebright − Edark can be either positive or negative. In this case, as long as the excitonic splitting |Δbd| is different for the 1st and 2nd sub-band transitions, which is generally true for SWNTs, the sign of Δbd could be opposite for E11 and E22 transitions when w1 and w2 take appropriate value (e.g., w1/w2 ~ 0.25 in Ref. 5). Recently, this issue was discussed theoretically in more detail by Oshima et. al.28 In their work, the bright-dark excitonic ordering is determined by the short-range cut-off of the Coulomb interaction. They predict that the dark exciton could be higher in energy than the bright one in the E22 transition, in general agreement with our results. Furthermore, family patterns were also predicted in their calculation: the negative splitting Δbd = Ebright − Edark is more likely to happen in Type I than in Type II nanotubes. However, this contradicts with our results. Our data shows that negative splitting happens for the (6,5) SWNTs, implying that it is Type II instead of Type I species that could have a negative excitonic splitting. This suggests that the model employed by Oshima et. al. is still oversimplified and more comprehensive calculations are needed to give a better interpretation for this phenomenon.

In summary, we performed high-field magneto-optical study on the relative ordering between bright and dark excitons in SWNTs for both 1st and 2nd sub-band transitions. The relative energy position of the dark exciton was identified by means of magnetic field brightening via the AB effect of SWNTs. For the 1st sub-band transition, the dark exciton was found to be lower than the bright one for any chiral SWNTs and is robust against environmental effect. For the 2nd sub-band, however, the bright-dark excitonic ordering was clarified to be chirality-sensitive: the dark exciton can be either higher or lower than the bright one, depending on the specific nanotube structures. As a promising material for nano-electronics, optical properties of SWNTs are governed by their excitonic structures. The unique chirality-sensitive bright-dark excitonic ordering discovered in this work tells us, that it is possible to control the optical properties of SWNTs by manipulating the ordering of their excitonic states. The family pattern behaviors, on the other hand, could serve as a guide to select nanotubes with desired excitonic structures. Thus, the findings in this work open up new possibilities for engineering the optical properties of SWNTs and will facilitate their commercial applications in the future.

Methods

Generation of ultra-high magnetic field

The ultra-high magnetic field up to 190 T was generated using the single-turn coil technique at the Institute for Solid State Physics, University of Tokyo. The single-turn coil system consists of a single-turn copper coil, an air gap switch and a fast capacitor bank (Energy: 200 kJ; Maximum charging voltage: 50 kV). The high current (mega-ampere scale) injected to the copper coil generates ultra-high magnetic field in the axis direction of the coil. The copper coil is destroyed each time by the large Maxwell stress. However, the sample and the optical setup survive because the coil explodes outward. Typical duration time of the pulsed magnetic field is ~7 μs. The highest magnetic field generated in this work is ~190 T using a copper coil with 10 mm inner diameter.

Magneto-absorption measurement

For the magneto-absorption measurements, we used a Xe arc flash lamp as the light source. Both incident and transmitted light was guided by optical fibers. For E11 measurements, we used an InGaAs diode array (XEVA-640, Xenics) as the detector. The E11 absorption spectra were taken only on the top of the pulsed magnetic field, with an exposed time chosen to be 1 μs to keep the field variation within 4% during the detector gate opening time. While for the E22 measurements, a streak camera (C4187-25S, Hamamatsu Photonics) was used and thus the magneto-absorption spectrum could be monitored continuously for the whole duration time of the pulsed magnetic field. All optical measurements were taken at room temperature under the Voigt geometry.

Alignment of the SWNT

(1) For the alignment of the SWNTs, we used a simple but efficient film-stretching technique. The SWNT dispersion was first mixed with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) solution and dried under ambient condition. Then the SWNTs/PVA film was stretched to ~5 times its original length by a home-made automated stretching machine. (2) Due to their one-dimensionality, optical responses of SWNTs are highly anisotropic. Excitation by light polarized perpendicular to the tube axis is strongly suppressed because of large depolarization effect. Based on this property, we could deduce the nematic order parameter S for the stretched SWNTs/PVA film. Definition of S is S = (3 <cos2θ> − 1)/2, with θ being the average angle between SWNT axis and the stretched direction of the SWNTs/PVA film. Value of the average angle θ can be extracted by correlating S to the optical anisotropy whose definition is A = (α∥ − α⊥)/(α∥ + 2α⊥), where α∥ and α⊥ are absorption intensities for light polarized parallel and perpendicular to SWNT axis, respectively. In this way, the average angle θ was estimated to be ~30° and ~29° for the (6,4) and (6,5) SWNTs, respectively.

Spectral correction for the E22 transition of the (6,4) sample

In the (6,4) sample, the (6,5) SWNTs exist as a minor species. In the E11 transition, absorption peaks from these two species is far away enough from each other and thus the (6,4) sample can still be regarded as a single chirality sample. In the E22 transition, the minor (6,5) species have an absorption peak lying on the short wavelength tail of the main (6,4) peak, with an intensity of ~15% compared to the (6,4) peak. To get rid of disturbance from the minor (6,5) species, we first measured the high-field magneto-absorption spectra of the (6,5) sample that has extremely high purity. Knowing the exact behavior of the (6,5) SWNTs in high magnetic fields, we could get the pure high-field absorption spectra for the E22 transition of the (6,4) SWNTs simply by subtracting contribution from the minor (6,5) species (FIG. S5–S8, Supporting Information).

Assignment of peaks to bright and dark excitons

Because of the AB effect, the dark exciton gains oscillator strength gradually with the increase of magnetic field. Thus, in the absorption spectrum, a new peak will emerge and its intensity grows with the magnetic field. This new peak should be assigned to the initially dark exciton and the other peak to the bright exciton.

References

O'Connell, M. J. et al. Band gap fluorescence from individual single-walled carbon nanotubes. Science 297, 593 (2002).

Bachilo, S. M. et al. Structure-assigned optical spectra of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Science 298, 2361 (2002).

Wang, F., Dukovic, G., Brus, L. E. & Heinz, T. F. The optical resonances in carbon nanotubes arise from excitons. Science 308, 838 (2005).

Ghosh, S., Bachilo, S. M. & Simonette, R. A. Oxygen doping modifies near-infrared band gaps in fluorescent single-walled carbon nanotubes. Science 330, 1656 (2010).

Ando, T. Effects of valley mixing and exchange on excitons in carbon nanotubes with Aharonov–Bohm flux. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 75, 024707 (2006).

Ando, T. Excitons in carbon nanotubes revisited: dependence on diameter, Aharonov–Bohm flux and strain. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 73, 3351 (2004).

Ando, T. Excitons in carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 66, 1066 (1997).

Wang, F., Dukovic, G., Brus, L. E. & Heinz, T. F. Time-resolved fluorescence of carbon nanotubes and its implication for radiative lifetimes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 177401 (2004).

Mortimer, I. B. & Nicholas, R. J. Role of bright and dark excitons in the temperature-dependent photoluminescence of carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 027404 (2007).

Kilina, S., Ramirez, J. & Tretiak, S. Brightening of the lowest exciton in carbon nanotubes via chemical functionalization. Nano Lett. 12, 2306 (2012).

Harutyunyan, H. et al. Defect-induced photoluminescence from dark excitonic states in individual single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 9, 2010 (2009).

Shaver, J. et al. Magnetic brightening of carbon nanotube photoluminescence through symmetry breaking. Nano Lett. 7, 1851 (2007).

Liu, H., Tanaka, T., Urabe, Y. & Kataura, H. High-Efficiency single-chirality separation of carbon nanotubes using temperature-controlled gel chromatography. Nano Lett. 13, 1996 (2013).

Liu, H., Nishide, D., Tanaka, T. & Kataura, H. Large-scale single-chirality separation of single-wall carbon nanotubes by simple gel chromatography. Nat. Commun. 2, 309 (2011).

Zhou, W. et al. Survey of exciton-phonon sidebands by magneto-optical spectroscopy using highly specified (6,5) single-walled carbon nanotubes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 021117 (2013).

Miura, N., Osada, T. & Takeyama, S. Research in super-high pulsed magnetic fields at the megagauss laboratory of the University of Tokyo. J. Low Temp. Phys. 133, 139 (2003).

Zaric, S. et al. Optical signatures of the Aharonov-Bohm phase in single-walled carbon nanotubes. Science 304, 1129 (2004).

Zaric, S. et al. Excitons in carbon nanotubes with broken time-reversal symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 016406 (2006).

Mortimer, I. B. et al. Magneto-optical studies of single-wall carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 76, 085404 (2007).

Lu, J. P. Novel magnetic properties of carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 1123 (1995).

Zhou, W. et al. Band-edge exciton states in a single-walled carbon nanotube revealed by magneto-optical spectroscopy in ultrahigh magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. B 87, 241406(R) (2013).

Matsunaga, R., Matsuda, K. & Kanemitsu, Y. Evidence for dark excitons in a single carbon nanotube due to the Aharonov-Bohm effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 147404 (2008).

Srivastava, A., Htoon, H., Klimov, V. I. & Kono, J. Direct observation of dark excitons in individual carbon nanotubes: inhomogeneity in the exchange splitting. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 087402 (2008).

Spataru, C. D., Ismail-Beigi, S., Capaz, R. B. & Louie, S. G. Theory and ab initio calculation of radiative lifetime of excitons in semiconducting carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 247402 (2005).

Perebeinos, V., Tersoff, J. & Avouris, P. Radiative lifetime of excitons in carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 5, 2495 (2005).

Takeyama, S., Suzuki, H., Yokoi, H., Murakami, Y. & Maruyama, S. Aharonov-Bohm exciton splitting in the optical absorption of chiral-specific single-walled carbon nanotubes in magnetic fields up to 78 T. Phys. Rev. B 83, 235405 (2011).

Nish, A., Nicholas, R. J., Faugeras, C., Bao, Z. & Potemski, M. High-field magnetooptical behavior of polymer-embedded single-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 78, 245413 (2008).

Oshima, T., Matsuno, K. & Suzuura, H. Energy splitting between bright and dark excitons in carbon nanotubes. Physica E 42, 779 (2010).

Acknowledgements

W. H. ZHOU thanks for the financial support of the post-doctoral research fellowship at the Institute for Solid State Physics, University of Tokyo. H. Kataura acknowledges support by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 25220602. H. Liu acknowledges supports by the “100 talents project” of CAS and the recruitment program of global youth experts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Z. performed all the experiments and analyzed the data. S.T. conceived and supervised the experiments. H.L. and H.K. performed sample purifications. D.N. provided support in the experiments. W.Z. wrote the paper. S.T. reviewed and corrected the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supporting Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, W., Nakamura, D., Liu, H. et al. Relative Ordering between Bright and Dark Excitons in Single-walled Carbon Nanotubes. Sci Rep 4, 6999 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06999

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06999

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.