Abstract

Quantum dynamics of light waves traveling through a time-varying turbulent plasma is investigated via the SU(1,1) Lie algebraic approach. Plasma oscillations that accompany time-dependence of electromagnetic parameters of the plasma are considered. In particular, we assume that the conductivity of plasma involves a sinusoidally varying term in addition to a constant one. Regarding the time behavior of electromagnetic parameters in media, the light fields are modeled as a modified CK (Caldirola-Kanai) oscillator that is more complex than the standard CK oscillator. Diverse quantum properties of the system are analyzed under the consideration of time-dependent characteristics of electromagnetic parameters. Quantum energy of the light waves is derived and compared with the counterpart classical energy. Gaussian wave packet of the field whose probability density oscillates with time like that of classical states is constructed through a choice of suitable initial condition and its quantum behavior is investigated in detail. Our development presented here provides a useful way for analyzing time behavior of quantized light in complex plasma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The problem of quantum light waves propagating through complex plasma has attracted considerable attention for several decades thanks to its rich applications in various physical systems. Some interesting applications include the diagnosis and analysis of plasma1,2 and frequency transformer producing terahertz radiation (T-ray)3,4,5. The research for the propagation of light waves in general time-varying media began in the late 1960s by Auld et al.6 and some other research groups7,8. Afterwards, wave phenomena in such media were actively investigated in the literature, especially focusing on the light waves traveling through time-varying plasma9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Collective modes of self-sustained oscillations of turbulent dusty plasmas around their equilibrium positions were observed in some situations and their physical properties have been studied2,17,18,19,20,21,22. The mechanism for realizing frequency up-conversion of light waves via their interaction with a suddenly created plasma slab was also reported23,24,25.

If we know analytical solutions of a quantum light wave, we can easily estimate quantum properties of the system and are able to predict its subsequent behaviors. However, most of the researches in this field have been performed numerically on the basis of the well known finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method4,9,26 or some other methods, due to the difficulty of mathematical procedure for analytical description of waves in complicated plasma. Inspired by this situation, we investigate how to derive analytical solutions of the Schrödinger equation for light waves in a time-varying plasma medium. Further, quantum properties of the system will be studied in detail by taking advantage of their exact quantum wave functions. For this purpose, we consider light waves propagating through a self-oscillating turbulent plasma. Plasma, which is a quasineutral gas, is composed of charged particles and neutral particles. Due to chargedness of their elements, plasma allow currents and, on account of electrical force within a pair of plus and minus ions in plasma, there is a tendency for the plasma to become neutral as a whole. If we consider that the electrical force acts like a restoring force, this property is, in essence, the origin of plasma oscillation. Indeed, in macroscopic point of view, the plasma oscillation takes place by a restoring force when neutral plasma is slightly deviated from an equilibrium position.

When plasma oscillate, the resulting electromagnetic parameters in media, such as conductivity, permeability and permittivity, may vary according to their specifically given oscillations. In this situation, the system is described by a time-dependent Hamiltonian, i.e., it belongs to a time-dependent harmonic oscillator. We will show that a periodical variation of the conductivity enables us to describe the light waves in media with a modified Caldirola-Kanai (CK) oscillator. Our scheme for modifying the standard CK oscillator as a model for describing time-varying plasma in this situation is replacing the constant damping factor of the standard CK oscillator27,28 with a factor that involves a sinusoidally varying term in addition to a constant one. If we consider that conductivity acts as a damping factor for light wave propagation, this corresponds to the exact response of wave motion when sinusoidally varying conductivity is involved as a specific character of the plasma. Recent increasing interest in plasma oscillation is not only due to its great assortment of collective modes for which it sustains, but also due to its value in probing the density of ionized particles on the basis of the sole dependence of oscillation frequency on charge density of plasma22. For other types of modified CK oscillator models, refer to Refs. 29,30,31.

The time-dependent harmonic oscillator model is very useful when investigating a system which has one or more time-dependent parameters and has attracted great interest from the early days of modern physics32,33,34,35,36,37. Quantum features of the modified CK oscillator model for light waves in plasma that have time-varying electromagnetic parameters will be described using an SU(1,1) Lie algebraic approach. Lots of novel quantum phenomena such as phase coherence, quantum correlation and quadrature squeezing can be explained through the use of the SU(1,1) Lie algebra, since it provides a useful formulae for describing the majority of quantum states29,37,38.

Results

Dynamics of light waves in time-varying plasma

Consider a light wave propagating in time-varying plasma which has no net charge density. Suppose that the magnetic permeability and the electric conductivity vary as time goes by, whereas the electric permittivity is constant for simplicity. Then, the speed of a light wave in the medium varies with time and is expressed as  , where

, where  is the electric permittivity and μ(t) is the time-dependent magnetic permeability, whereas the wave number k is constant. The basic relations between fields in such time-varying plasma are given by

is the electric permittivity and μ(t) is the time-dependent magnetic permeability, whereas the wave number k is constant. The basic relations between fields in such time-varying plasma are given by  and B = μ(t)H. Meanwhile, the relation between current density and electric field is J = σ(t)E, where σ(t) is the time-dependent electric conductivity.

and B = μ(t)H. Meanwhile, the relation between current density and electric field is J = σ(t)E, where σ(t) is the time-dependent electric conductivity.

Let us take the Coulomb gauge for the sake of simplicity. Then, the scalar potential vanishes in (net) charge free space and, hence, we only need to consider the expansion of the vector potential in order to develop electromagnetic theory of the system. By representing the vector potential in the form

it is able to separate the position and the time functions. The solutions of the system are entirely determined by Maxwell's equations. The position function is determined by the geometry of boundaries of plasma while the time function follows the equation36

where ω(t) = kc(t). For σ(t) = σ(0) and μ(t) = μ(0), our model reduces to that described by the familiar standard CK oscillator. As is well known, the standard CK oscillator is an elementary system for describing a damped harmonic oscillator characterized by a constant damping factor. The modification of the system from the standard CK oscillator in our model is mainly determined by the time behavior of σ(t).

Each particle in the plasma is arranged in such a way that the net force exerted to a particle from all other particles becomes zero, leading to a homogeneous neutral state of charge. If an electron moves from such equilibrium position, a positive charge is generated in the equilibrium position and there arises electric forces between this new positive charge and surrounding electrons. This leads the electron to oscillate. Since the interaction between electrons is very large, each electron oscillates with a characteristic frequency determined depending on properties of the plasma. Under such plasma oscillations3, we assume that there is a sinusoidally varying term in the conductivity of media, as well as a constant one, such that

where a and b are arbitrary positive constants and ϖ is a constant frequency of conductivity oscillation. In this model, σ is always positive for the case that a > b, whereas it is both positive and negative, in turn, whenever a < b. The properties of plasma with the negative value of σ have been studied in Refs. 3 and 39. However, in most cases, b is very small compared to a. Another example of conductivity oscillation is the Shubnikov-de Haas effect40,41,42. This oscillation is a macroscopically observed intrinsic quantum nature of matter which appears when the material is subjected to very intense magnetic fields with the upkeep of low temperature.

The quantum Hamiltonian that corresponds to the classical equation of motion, Eq. (2), can be represented as

where  . The time function Λ(t) is given by

. The time function Λ(t) is given by

where  is a constant. From Eq. (4), we see that the Hamiltonian of the system is time-dependent. Note that the time dependency of Λ(t) does not disappear even when b = 0. Therefore, the standard CK oscillator is also a family of time-dependent harmonic oscillator.

is a constant. From Eq. (4), we see that the Hamiltonian of the system is time-dependent. Note that the time dependency of Λ(t) does not disappear even when b = 0. Therefore, the standard CK oscillator is also a family of time-dependent harmonic oscillator.

Formulation of wave function from SU(1,1) Lie algebra

A useful way for investigating complex dynamical systems is to introduce SU(1,1) Lie Algebraic operators associated with a given system. A broad range of oscillator-like problems in physics is well described in terms of SU(1,1) Lie algebra29,37,38,43,44. Accordingly, many authors have used this algebraic method to unfold both classical and quantum theories of optical systems. The phase properties of a quantized light which exhibits nonclassical properties have been theoretically investigated by Gerry by means of SU(1,1) Lie algebras38. This algebra can also be successfully used for the purposes of studying coherence and squeezing properties of photons, analyzing quantum mechanical interferometers and beam splitters, investigating dissipative processes in quantum optical systems and so on44.

According to the SU(1,1) Lie algebraic theory29,37,38, we introduce SU(1,1) generators that are suitable for our system such that

where Ω is a real positive constant and ρ(t) is a time-function that satisfies the differential equation of the form

Equation (9) is a modified form of the Milne equation45. Although we focus on analytical investigation of light waves, the Milne equation is also useful for studying numerical analysis of mechanical systems46. If  where ω0 is a constant, Eqs. (6)–(8) recover to those of the simple harmonic oscillator. The commutation relations between generators are

where ω0 is a constant, Eqs. (6)–(8) recover to those of the simple harmonic oscillator. The commutation relations between generators are  ,

,  and

and  . At this stage, it can be easily checked that the direct differentiation of Eq. (6) results in zero:

. At this stage, it can be easily checked that the direct differentiation of Eq. (6) results in zero:

This means that  is a time-constant.

is a time-constant.

Now we define the raising and the lowering operators to be

These also yield the usual commutation relations which are  and

and  . Considering that the eigenvalue of the Casimir operator,

. Considering that the eigenvalue of the Casimir operator,  , is given by k(k − 1) = −3/16, we can confirm that the Bargmann index is k = 1/4 or k = 3/4. The basis of the unitary space is a set of an even boson number for k = 1/4 and an odd boson number for k = 3/4.

, is given by k(k − 1) = −3/16, we can confirm that the Bargmann index is k = 1/4 or k = 3/4. The basis of the unitary space is a set of an even boson number for k = 1/4 and an odd boson number for k = 3/4.

If we use the properties of SU(1,1) operators, it is possible to derive the wave functions of the light wave propagating through the plasma medium. From the procedure represented in the latter section, Methods, we can confirm that the wave functions in the Fock state are given by

where  are the eigenstates of

are the eigenstates of  :

:

and θn(t) are time-dependent phases of the form

These wave functions are very useful when investigating quantum characteristics of the system and agree well with those obtained from other methods irrelevant to Lie algebraic scheme47. For instance, the quantum fluctuation of canonical variables and the expectation value of quantum energy can be identified using the wave functions. Notice that the exact knowledge of ρ(t) that can be obtained from Eq. (9) is crucial for analyzing the time behavior of the wave functions.

Analysis of quantum behaviors

Our research in this work can be applied to diverse particular cases by choosing the time-dependent angular frequency ω(t) given in Eq. (2). Let us consider one of the solvable cases in which ω(t) is given by

where ω0 is a positive constant and

Let us first see the classical features of this system. The classical energy of the light wave can be expressed as

where  . The classical solution of Eq. (2) in this case is given by

. The classical solution of Eq. (2) in this case is given by

where q0 and φ are arbitrary constants while, from Hamilton's equation, the canonical momentum becomes  . If we insert these quantities, q(t) and p(t), in Eq. (17), we have

. If we insert these quantities, q(t) and p(t), in Eq. (17), we have

The envelope of this energy decays with time due to the exponential factor e−Λ(t).

Now we turn our attention to quantum features of the system. From previous sections, we have seen that the quantum solutions are expressed in terms of the classical solution ρ(t). Hence, to investigate the quantum systems completely for particular cases, it is necessary to solve Eq. (9). In this case, we can easily verify that the solution of Eq. (9) is represented in the form

Using this, Eq (12) can be rewritten as

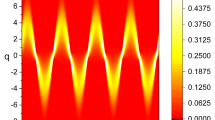

The probability densities which are the square of this equation,  , are illustrated in Fig. 1, where we have chosen n = 5 as an example. Six peaks, that each corresponds to a highly concentrated local probability density, are found in this figure along the q-axis at any given time. This proves to be the same result as in the case of the well known simple harmonic oscillator. In general there are n + 1 regions of locally high probability density for nth quantum state. As you can see, the probability density converges to the origin where q = 0 as a whole. This means that the amplitude of the wave packet dissipates with time due to the existence of conductivity.

, are illustrated in Fig. 1, where we have chosen n = 5 as an example. Six peaks, that each corresponds to a highly concentrated local probability density, are found in this figure along the q-axis at any given time. This proves to be the same result as in the case of the well known simple harmonic oscillator. In general there are n + 1 regions of locally high probability density for nth quantum state. As you can see, the probability density converges to the origin where q = 0 as a whole. This means that the amplitude of the wave packet dissipates with time due to the existence of conductivity.

Fock state wave packet, |〈q|ψn(t)〉|2, where the wave function is given by Eq. (21).

The values we used are given by  ,

,  , a = 0.03, b = 0.01, ϖ = 0.1, δ0 = 0, ω0 = 5 and n = 5.

, a = 0.03, b = 0.01, ϖ = 0.1, δ0 = 0, ω0 = 5 and n = 5.

We can investigate various quantum properties of the system using the wave functions given in Eq. (21). As an example, we consider the expectation value of quantized energy of the system. The energy operator of the system is easily obtained by replacing q and p in Eq. (17) with operators  and

and  :

:

The expectation value of this operator can be obtained with the use of Eq. (21), such that

where

These quantum energies dissipate over time according to the decrease of wave amplitude caused by the nonzero conductivity in plasma. The comparison of the quantum energy and the classical energy represented in Eq. (19) is given in Fig. 2. The time behavior of the quantum energy is very similar to that of the classical energy in most cases [see Fig. 2(a)], but sometimes they are somewhat different from each other [see Fig. 2(b) and 2(c)]. One of the reasons for this discrepancy of quantum energy with the classical one is the existence of the zero-point energy in quantum energy as a pure quantum effect.

Comparison of quantum energy Eq. (23) (dashed red line) with the classical energy Eq. (19) (solid blue line).

The values of (ω0, ϖ, b, q0) are (5, 1, 0.1, 0.775) for (a), (0.5, 10, 0.01, 2.45) for (b) and (0.5, 10, 0.05, 2.45) for (c). All other values are common and given by  ,

,  , n = 1, a = 0.3, δ0 = 0 and φ = 0.

, n = 1, a = 0.3, δ0 = 0 and φ = 0.

If we take the time average of Eq. (19) only for the oscillation relevant to the frequency represented in terms of ω0, we have

Thus, we can confirm that the time behavior of the quantum energy Eq. (23) is very similar to this time-averaged classical energy.

The general wave function is the collection of all possible wave functions with order n in the Fock space:

where cn are amplitudes of nth Fock state wave function, which yield ∑n|cn|2 = 1. As a further illustration, let us consider an initial wave function of the form

where β1 and β2 are arbitrary constants which are complex. Without loss of generality, we can put  where ϑ1 is an arbitrary constant. β2 can also be represented in the same way. If we denote that βj = Re(βj) + iIm(βj) (j = 1, 2) where Re(βj) and Im(βj) are real and imaginary parts of βj, from the normalization condition of this wave function, we have the following relation that should be imposed here

where ϑ1 is an arbitrary constant. β2 can also be represented in the same way. If we denote that βj = Re(βj) + iIm(βj) (j = 1, 2) where Re(βj) and Im(βj) are real and imaginary parts of βj, from the normalization condition of this wave function, we have the following relation that should be imposed here

The amplitude of the nth order wave function is easily computed from

Using Eqs. (21) and (27), cn becomes

By inserting the above equation and Eq. (21) into Eq. (26), we have

This is the central result of our research. For t = 0, this equation recovers to Eq. (27) as expected. If we consider that no approximation is used up to now, the time behavior of the wave function, Eq. (31), is exact. Many authors rely on numerical methods4,9,26,48,49,50 in order to analyze complicated phenomena of light propagation in time-varying plasma. However, we no longer need numerical simulation in case it is possible to know exact analytical solutions. The analytical solution given in Eq. (31) is very convenient when estimating the time behavior of the light waves thanks to its flexible applicability in any situation. Moreover, its derivation requires no iteration procedure which is necessary when we find a new solution at different times or with other choices of parameters using numerical simulation.

Now, one can easily verify that the probability density can be represented as a simple form which is a Gaussian wave packet:

where

In the derivation of Eq. (32), we used the relation given in Eq. (28). Because we see from Eq. (33) that the width ν(t) of the Gaussian wave packet is proportional to e−Λ(t)/2 and it is known from Eq. (5) that Λ(t) increases with time, the leading behavior of the width of the packet is that it becomes exponentially narrower with time while the height  increases. This implies the appearance of dissipative characteristics of the Gaussian wave packet in response to the presence of conductivity σ(t). If we consider that the value in the parenthesis of Eq. (34) can be rewritten as

increases. This implies the appearance of dissipative characteristics of the Gaussian wave packet in response to the presence of conductivity σ(t). If we consider that the value in the parenthesis of Eq. (34) can be rewritten as  , the center of the Gaussian wave packet oscillates sinusoidally with time like a classical state. We can also confirm these facts from Fig. 3. Figure 3(a) exhibits a high-frequency oscillation of the wave packet with relative high ω0, whereas Fig. 3(b) a low-frequency oscillation. Except for such dynamical oscillations of the packet, the time-varying behavior of the amplitude of packets given in Fig. 3 is largely similar to that of the Fock state represented in Fig. 1.

, the center of the Gaussian wave packet oscillates sinusoidally with time like a classical state. We can also confirm these facts from Fig. 3. Figure 3(a) exhibits a high-frequency oscillation of the wave packet with relative high ω0, whereas Fig. 3(b) a low-frequency oscillation. Except for such dynamical oscillations of the packet, the time-varying behavior of the amplitude of packets given in Fig. 3 is largely similar to that of the Fock state represented in Fig. 1.

Oscillation of Gaussian wave packet given in Eq. (32).

The values of ( , a, b, ϖ, ω0, |β1|, ϑ1) are (0.13, 0.03, 0.01, 10, 10, 0.3, 2) for (a) and (1, 0.1, 0.03, 5, 1, 1, 1) for (b). All other values are common and given by

, a, b, ϖ, ω0, |β1|, ϑ1) are (0.13, 0.03, 0.01, 10, 10, 0.3, 2) for (a) and (1, 0.1, 0.03, 5, 1, 1, 1) for (b). All other values are common and given by  and δ0 = 0.

and δ0 = 0.

The probability that represents the contribution of nth Fock state wave to the total wave packet is given by

Using this and Eq. (23), the mean value of energy for the Gaussian wave is evaluated to be

where  is the mean value of quantum numbers contributed to the packet, that is given by

is the mean value of quantum numbers contributed to the packet, that is given by  . In addition, the dispersion of energy is obtained from

. In addition, the dispersion of energy is obtained from

A straightforward calculation gives

This also decreases with time and is proportional to  .

.

We have shown up until now that the quantum wave packets in time-varying plasma converge to the origin, where q = 0, with time. Along this convergence, the quantum energy also dissipates. In the case that σ(t) → 0, the overall dissipation discussed in this section vanishes. We confirmed that the Gaussian wave packet, Eq. (32), oscillates like that of the classical states. The analysis of quantum light waves given here may provide a useful method for treating quantum behavior of light waves in complex plasma.

Discussion

The modified CK oscillator model is considered in order to investigate the analytic properties of light waves in time-varying plasma whose electromagnetic parameters such as magnetic permeability and electric conductivity vary with time. The main factor that characterizes our model is the time behavior of the conductivity given in Eq. (3). One of prospect applications of the modified CK oscillator is the quantization problem of radiation fields in time-varying media like dynamical plasma. The conductivity of a plasma medium is responsible for the damping of a light wave propagating through it. Hence, if the conductivity vanishes and other electromagnetic parameters are constant, the radiation field does not dissipate with time and it merely corresponds to that of the case described by the simple harmonic oscillator.

Through different choices of time-dependent parameters, our research can be applied to analyzing quantum behaviors of light waves in plasma under various situations of plasma process. When b → 0 and μ(t) → μ0 (constant), our model recovers to that of the standard CK oscillator, whereas, in the case that a → 0, it becomes a somewhat different model of a modified CK oscillator given in Ref. 51.

To study the quantum problem of light waves in time-varying plasma, the SU(1,1) Lie algebraic formulation of quantum theory is used. The SU(1,1) generators  ,

,  and

and  are introduced as shown in Eqs. (6)–(8). The raising and the lowering operators associated with this algebra are also constructed and we took advantage of them in order to derive the exact wave functions of the system in the Fock state. Quantum solutions and further results for light waves are described in terms of the classical solution ρ(t) of a modified Milne equation45 given in Eq. (9). We can say that the obtainability of quantum solutions is determined by the solvability of Eq. (9). In fact, the solution of the Milne equation can be represented in terms of two linearly independent solutions of classical light wave, i.e., the solutions of Eq. (2)46. For this reason, we are able to obtain ρ(t) provided that two linear independent solutions of Eq. (2) are known or derivable. This implies that the complete quantum solutions can be obtained according to our theory based on the SU(1,1) Lie algebraic approach, so long as the solutions of corresponding classical light waves are solved. Hence, we can analyze the overall quantum characteristics of light waves on the basis of such solutions. Indeed, this point is a great advantage when implementing our novel method in the light wave research. Notice that our description of quantum light waves requires no approximation or perturbation technique whatsoever.

are introduced as shown in Eqs. (6)–(8). The raising and the lowering operators associated with this algebra are also constructed and we took advantage of them in order to derive the exact wave functions of the system in the Fock state. Quantum solutions and further results for light waves are described in terms of the classical solution ρ(t) of a modified Milne equation45 given in Eq. (9). We can say that the obtainability of quantum solutions is determined by the solvability of Eq. (9). In fact, the solution of the Milne equation can be represented in terms of two linearly independent solutions of classical light wave, i.e., the solutions of Eq. (2)46. For this reason, we are able to obtain ρ(t) provided that two linear independent solutions of Eq. (2) are known or derivable. This implies that the complete quantum solutions can be obtained according to our theory based on the SU(1,1) Lie algebraic approach, so long as the solutions of corresponding classical light waves are solved. Hence, we can analyze the overall quantum characteristics of light waves on the basis of such solutions. Indeed, this point is a great advantage when implementing our novel method in the light wave research. Notice that our description of quantum light waves requires no approximation or perturbation technique whatsoever.

As a particular case, we considered the light wave that has the natural frequency of Eq. (15). The wave functions in the Fock state are given by Eq. (21) and the corresponding probability densities are illustrated in Fig. 1. As time goes by, the wave packet converges to the origin where q = 0. It is shown that the time behavior of the quantum energy of light waves agrees well with that of the classical energy in most cases under the specific choice of the value of parameters, as shown in Fig. 2(a). However, in some cases, the quantum energy somewhat deviates from the classical one [see Figs. 2(b) and 2(c)]. One of the reasons for this discrepancy is the existence of the zero-point energy in quantum cases. By choosing the initial wave packet as Eq. (27), we obtained the Gaussian wave packet that oscillates like a classical wave. The width of the Gaussian wave packet given in Fig. 3 was gradually narrowed as time went by due to the existence of conductivity in the media. This implies that the light waves dissipate with time. Indeed, conductivity acts like a damping factor for the traveling fields.

The current mainstream of the research for the properties of light propagation in complex time-varying media is to use numerical methods such as the FDTD method4,9,26, the TMM (transfer matrix method)48, the BPM (beam propagation methods)26,49 and the FEM (finite element method)50. However, in principle, numerical simulation is a second alternative chosen when we are unable to find analytical solutions. Due to the intrinsic limitation inherent in numerical methods, a solution obtained from a numerical simulation at a certain time t is inadequate to be used for further analysis at a later time. For this reason, analytical solutions for the time evolution of light waves, such as Eq. (31), are very important for identifying their overall time behavior in complicated time-varying media. Apparently, even if the time variation of the system is somewhat complex, we can flexibly use this analytical solution without necessity of paying attention to the change of the parameters in plasma.

As a final remark, our research can be applied to various fields in science and technology. Among them, the real-time state of plasma in a tokamak where nuclear fusion takes place can be analyzed and diagnosed by monitoring the radiation fields propagating through it, leading to keep the optimal condition for nuclear fusion4. The physical conditions of plasma in a tokamak, such as temperature, pressure and ionization, are closely related to the state of radiation fields in it, which we have studied here. The exact real-time check for the status of plasma in a tokamak is crucial for efficient and rigorous control of the whole procedure during the generation of fusion energy. Another useful application is biomedical THz imaging10 which is a very promising research field in biomedical science and engineering. The radiation fields within the frequency range of 0.1–10 THz are known as T-rays. The T-rays occupy a large part of the frequency band, involving both microwave and infrared and relatively do not developed further when compared to other rays. Our theory developed here can be used to provide a theoretical background for frequency transformers which are necessary for producing T-rays. T-rays are obtained by transforming frequencies of beams that initially have other range of frequencies, because there is no known natural source of T-rays with sufficient efficiency yet.

Methods

Here we represent how to derive wave functions of quantum light wave via the SU(1,1) Lie algebraic approach. If we denote the nth eigenfunction of  as |ϕn〉, it can be easily verified that

as |ϕn〉, it can be easily verified that

These properties are necessary when we derive quantum states of the system. From the condition that

we derive the ground state eigenfunction of K0 to be

On the same ground, the first excited eigenfunction, 〈q|ϕ1〉, is also obtained by solving  . Further, the even order excited eigenfunctions 〈q|ϕn= 2m〉 (

. Further, the even order excited eigenfunctions 〈q|ϕn= 2m〉 ( ) can be evaluated by operating

) can be evaluated by operating  m times in 〈q|ϕ0〉 [Eq. (42)] and the odd order excited eigenfunctions 〈q|ϕn= 2m+1〉 can also be obtained by the same operation in 〈q|ϕ1〉. Eventually, by merging the corresponding two results37, we have the normalized full eigenfunctions, 〈q|ϕn〉, which are represented in Eq. (13).

m times in 〈q|ϕ0〉 [Eq. (42)] and the odd order excited eigenfunctions 〈q|ϕn= 2m+1〉 can also be obtained by the same operation in 〈q|ϕ1〉. Eventually, by merging the corresponding two results37, we have the normalized full eigenfunctions, 〈q|ϕn〉, which are represented in Eq. (13).

Now, by solving the eigenvalue equation,  , we get the eigenvalues of

, we get the eigenvalues of  as

as  . If we recall from Eq. (10) that

. If we recall from Eq. (10) that  is a time-constant, this result which exhibits that λn is not a function of t is natural.

is a time-constant, this result which exhibits that λn is not a function of t is natural.

According to the Lewis-Riesenfeld theory for a quantization of the time-dependent harmonic oscillator32, the wave functions are represented in terms of the eigenfunctions 〈q|ϕn〉 as shown in Eq. (12). However, the phases θn(t) of the wave functions are undetermined yet. By inserting the equation  , where 〈q|ϕn〉 are given by Eq. (13), together with Eq. (4) into the Schrödinger equation, we can derive the exact phases32,37,47. Thus, through this procedure, the full wave functions of the system in the Fock state are derived as given in Eq. (12) with Eqs. (13) and (14).

, where 〈q|ϕn〉 are given by Eq. (13), together with Eq. (4) into the Schrödinger equation, we can derive the exact phases32,37,47. Thus, through this procedure, the full wave functions of the system in the Fock state are derived as given in Eq. (12) with Eqs. (13) and (14).

References

Heald, M. A. & Wharton, C. B. Plasma Diagnostics with Microwaves (New York, Wiley, 1965).

Vyacheslavov, L. N. et al. Diagnostics of strong Langmuir turbulence. Plasma Phys. Rep. 24, 183–190 (1998).

Ryzhii, V., Ryzhii, M., Shur, M. S. & Mitin, V. Negative terahertz dynamic conductivity in electrically induced lateral p-i-n junction in graphene. Physica E 42, 719–721 (2010).

Kalluri, D. K. Electromagnetics of Time Varying Complex Media 2nd ed. (Boca Raton, CRC Press, 2010).

Knap, W. et al. Terahertz emission by plasma waves in 60 nm gate high electron mobility transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 2331–2333 (2004).

Auld, B. A., Collins, J. H. & Zapp, H. R. Signal processing in a nonperiodically time-varying magnetoelastic medium. Proc. IEEE 56, 258–272 (1968).

Felsen, L. & Whitman, G. Wave propagation in time-varying media. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propagat. AP-18, 242–253 (1970).

Fante, R. L. Transmission of electromagnetic waves into time-varying media. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propagat. AP-19, 417–424 (1971).

Lee, J. H. & Kalluri, D. K. Three-dimensional FDTD simulation of electromagnetic wave transformation in a dynamic inhomogeneous magnetized plasma. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propagat. 47, 1146–1151 (1999).

Budko, N. V. Electromagnetic radiation in a time-varying background medium. Phys. Rev. A 80, 053817 (2009).

Monroe, R. L. Electromagnetic radiation in a time-varying plasma. J. Appl. Phys. 41, 560–562 (1970).

Yang, L.-X., Shen, D.-H. & Shi, W.-D. Analyses of electromagnetic scattering characteristics for 3D time-varying plasma medium. Acta Phys. Sin. 62, 104101 (2013).

He, G. et al. Channel characterization and finite-state Markov channel modeling for time-varying plasma sheath surrounding hypersonic vehicles. Prog. Electromag. Res. 145, 299–308 (2014).

Liu, S., Liu, S. & Yuan, N. FDTD simulation of bistatic scattering by conductive cylinder covered with inhomogeneous time-varying plasma. Plasma Sci. Technol. 8, 190–194 (2006).

Liu, S., Mo, J. & Yuan, N. FDTD simulation of electromagnetic reflection of conductive plane covered with inhomogeneous time-varying plasma. Int. J. Infrared Milli. Waves 23, 1179–1191 (2002).

Lee, J. H., Kalluri, D. K. & Nigg, G. C. FDTD simulation of electromagnetic wave transformation in a dynamic magnetized plasma. Int. J. Infrared Milli. Waves 21, 1223–1253 (2000).

Cho, S. N. Mechanism behind self-sustained oscillations in direct current glow discharges and dusty plasmas. Phys. Plasmas 20, 043708 (2013).

Zubtsov, V. M., Sinkevich, O. A. & Chuklova, V. T. Origination of a self-oscillating mode (magnetic striations) in a nonequilibrium magnetized plasma. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 19, 296–302 (1978).

Fleishman, G. D. & Toptygin, I. N. Diffusive radiation in one-dimensional Langmuir turbulence. Phys. Rev. E 76, 017401 (2007).

Vyacheslavov, L. N. et al. Strong Langmuir turbulence with and without collapse: Experimental study. Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 44 (12 B SPEC), B279–B291 (2002).

Ossipenko, M. V. & Tsaun, S. V. Description of turbulent convection in a plasma with the help of interacting Lorentz oscillators. Plasma Phys. Rep. 26, 465–476 (2000).

Kulin, S., Killian, T. C., Bergeson, S. D. & Rolston, S. L. Plasma oscillations and expansion of an ultracold neutral plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 318–321 (2000).

Savage, R. L., Jr, Joshi, C. J. & Mori, W. B. Frequency up-conversion of electromagnetic radiation upon transmission into an ionization front. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 946–949 (1992).

Wilks, S. C., Dawson, J. M. & Mori, W. B. Frequency up-conversion of electromagnetic radiation with use of an overdense plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 337–340 (1988).

Kuo, S. P. Frequency up-conversion of microwave pulse in a rapidly growing plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 1000–1003 (1990).

Vukovic, A., Bekker, E. V., Sewell, P. & Benson, T. M. Efficient time domain modeling of rib waveguide RF modulators. J. Lightwave Technol. 24, 5044–5053 (2006).

Caldirola, P. Porze non conservative nella meccanica quantistica. Nuovo Cimento 18, 393–400 (1941).

Kanai, E. On the quantization of dissipative systems. Prog. Theor. Phys. 3, 440–442 (1948).

Ozeren, S. F. The effect of nonextensivity on the time evolution of the SU(1,1) coherent states driven by a damped harmonic oscillator. Physica A 337, 81–88 (2004).

Abdalla, M. S. & Colegrave, R. K. Harmonic oscillator with strongly pulsating mass under the action of a driving force. Phys. Rev. A 32, 1958–1964 (1985).

Ikot, A. N., Akpabio, L. E. & Antia, A. D. Path integral of time-dependent modified Caldirola-Kanai oscillator. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 37, 217–224 (2012).

Lewis, H. R., Jr & Riesenfeld, W. B. An exact quantum theory of the time-dependent harmonic oscillator and of a charged particle in a time-dependent electromagnetic field. J. Math. Phys. 10, 1458–1473 (1969).

Yeon, K. H., Kim, D. H., Um, C. I., George, T. F. & Pandey, L. N. Relations of canonical and unitary transformations for a general time-dependent quadratic Hamiltonian system. Phys. Rev. A 55, 4023–4029 (1997).

Choi, J. R. & Gweon, B. H. Operator method for a nonconservative harmonic oscillator with and without singular perturbation. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 16, 4733–4742 (2002).

Choi, J. R. & Choi, S. S. Investigation of the coherent wave packet for a time-dependent damped harmonic oscillator. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 17, 495–508 (2005).

Choi, J. R. & Yeon, K. H. Quantum properties of light in linear media with time-dependent parameters by Lewis-Riesenfeld invariant operator method. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 19, 2213–2224 (2005).

Choi, J. R. & Nahm, I. H. SU(1,1) Lie algebra applied to the general time-dependent quadratic Hamiltonian system. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 46, 1–15 (2007).

Gerry, C. C. Phase operators for SU(1,1): Application to the squeezed vacuum. Phys. Rev. A 38, 1734–1738 (1988).

Ryzhii, V., Ryzhii, M., Mitin, V., Satou, A. & Otsuji, T. Effect of heating and cooling of photogenerated electron-hole plasma in optically pumped graphene on population inversion. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 50, 094001 (2011).

Wosnitza, J. et al. Shubnikov-de Haas effect in the superconducting state of an organic superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 62, R11973–R11976 (2000).

Linke, H. et al. Application of microwave detection of the Shubnikov-de Haas effect in two-dimensional systems. J. Appi. Phys. 73, 7533–7542 (1993).

Balicas, L. et al. Shubnikov-de Haas effect in the metallic state of Na0.3CoO2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 126401 (2006).

Inomata, A., Kuratsuji, H. & Gerry, C. C. Path Integrals and Coherent States of SU(2) and SU(1,1) (Singapore, World Scientific, 1992).

Ban, M. SU(1,1) Lie algebraic approach to linear dissipative processes in quantum optics. J. Math. Phys. 33, 3213–3228 (1992).

Milne, W. E. The numerical determination of characteristic numbers. Phys. Rev. 35, 863–867 (1930).

Korsch, H. J. & Laurent, H. Milne's differential equation and numerical solutions of the Schrödinger equation I. Bound-state energies for single- and double-minimum potentials. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Phys. 14, 4213–4230 (1981).

Choi, J. R. Nonclassical properties of superpositions of coherent and squeezed states for electromagnetic fields in time-varying media. Quantum Optics and Laser Experiments Lyagushyn, S. (ed.), 25–48, (Rijeka, Intech, 2012).

Carretero, L., Perez-Molina, M., Acebal, P., Blaya, S. & Fimia, A. Matrix method for the study of wave propagation in one-dimensional general media. Opt. Express 14, 11385–11391 (2006).

Fesenko, V. I., Sukhoivanov, I. A., Shulga, S. N. & Andrade Lucio, J. A. Propagation of electromagnetic waves in anisotropic photonic structures. Advances in Photonic Crystals Passaro, V. M. N. (ed.), 79–105 (Rijeka: Intech; 2013).

Ninan, M., Zhengyi, J. & Dongbin, W. Analysis of multi-layer sandwich structures by finite element method. Adv. Sci. Lett. 4, 3243–3248 (2011).

Ikot, A. N., Akpabio, L. E., Akpan, I. O., Umo, M. I. & Ituen, E. E. Quantum damped mechanical oscillator. Int. J. Opt. 2010, 275910 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program of the year 2014 through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (Grant No.: NRF-2013R1A1A2062907).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.R.C. wrote the paper and approved it.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, J. A novel method for analyzing complicated quantum behaviors of light waves in oscillating turbulent plasma. Sci Rep 4, 6880 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06880

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06880

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.