Abstract

High-performance ultra-thin oxide layers are required for various next-generation electronic and optical devices. In particular, ultra-thin resistive switching (RS) oxide layers are expected to become fundamental building blocks of three-dimensional high-density non-volatile memory devices. Until now, special deposition techniques have been introduced for realization of high-quality ultra-thin oxide layers. Here, we report that ultra-thin oxide layers with reliable RS behavior can be self-assembled by field-induced oxygen migration (FIOM) at the interface of an oxide-conductor/oxide-insulator or oxide-conductor/metal. The formation via FIOM of an ultra-thin oxide layer with a thickness of approximately 2–5 nm and 2.5% excess oxygen content is demonstrated using cross-sectional transmission electron microscopy and secondary ion mass spectroscopy depth profile. The observed RS behavior, such as the polarity dependent forming process, can be attributed to the formation of an ultra-thin oxide layer. In general, as oxygen ions are mobile in many oxide-conductors, FIOM can be used for the formation of ultra-thin oxide layers with desired properties at the interfaces or surfaces of oxide-conductors in high-performance oxide-based devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Owing to its large effect on structural and electromagnetic properties, migration of cations and oxygen ions in oxide materials has been extensively investigated. In particular, the concentration and distribution of oxygen ions play an important role in determining the performance of electrical and optical devices1,2,3,4,5. Recently, in order to develop high-performance electronic devices based on emerging oxide materials, such as thin film transistors, oxide diodes, photovoltaic devices, memristors, resistive random access memories (ReRAMs), ferroelectric random access memories (FeRAMs)5,6,7,8,9,10, many researchers have focused their efforts on precisely controlling the concentration and distribution of oxygen ions through various deposition methods, including electric field modulation, post-annealing process, or buffered layer structure11,12,13,14,15,16,17.

Among several electronic devices, ReRAMs using resistive switching (RS) behavior induced by an external electric stress show excellent advantages. For instance, they have simple and highly scalable two terminal structures, high resistive switching speed, low power consumption and material diversity that includes oxides, polymers and chalcogenides12,13,14,18,19,20. In RS oxide materials, innovative performance and scaling-down require that RS phenomena are confined to nanostructures (such as nanoparticles, nanowires and ultra-thin films)21,22,23,24,25,26. These phenomena are closely related to changes in concentration or distribution of oxygen ions under an external electric field. Specifically, unipolar RS is caused by a change in stoichiometry between transition metal and oxygen ions9,12,13,27, while bipolar RS is induced by oxygen migration into the active interfacial layer3,5,22,23,24. As a result, the ability to manipulate oxygen ions using an external electric field to fabricate self-assembled oxide nanostructures with RS behavior is very interesting and sought after, although major results are yet to be achieved.

In this paper, we report on the fabrication of self-assembled ultra-thin oxide layers by the field-induced oxygen migration (FIOM) technique at oxide-conductor/oxide-insulator or oxide-conductor/metal junctions. Al-doped (4 wt %) ZnO (AZO) is a well-known transparent conductive oxide (TCO). Combining Al with ZnO leads to high conductivity, enhancing oxygen migration under external electric field and Joule heating, which reduce the activation energy for the migration of oxygen atoms28,29,30. Therefore, it is expected that an external electric field can easily induce migration of oxygen ions in AZO depending on the bias polarity. In AZO/NiO/Pt structures, an ultra-thin oxygen-rich (O-rich) AZO layer is formed at the AZO/NiO interface under negative bias polarity. Here, we report for the first time, to the best of our knowledge, the formation of a self-assembled ultra-thin O-rich AZO layer, as shown by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and secondary ion mass spectroscopy (SIMS) depth profile. This layer shows reliable unipolar RS behavior. Moreover, to confirm the suitability of the FIOM technique, we demonstrate that ultra-thin RS oxide layers are self-assembled by external electric field at TCO/Pt interfaces where Pt and TCO, such as AZO and Cu-doped ZnO (CZO), are non-RS and conducting materials.

Results and Discussion

To create self-assembled ultra-thin oxide layers, we fabricated AZO/NiO/Pt structures with insulating NiO as a buffer layer. The electric potential difference, which can drive oxygen migration, can be controlled in the AZO layer by varying the thickness of the NiO buffer layer (schematic illustration in the inset of Fig. 1a). NiO films were deposited on Pt/Ti/SiO2/Si substrates using a DC sputtering technique. Subsequently, AZO electrodes with a thickness of 200 nm and an area of 50 × 50 μm2 were deposited on the NiO/Pt structure using the RF sputtering method and conventional lift-off process (see methods section).

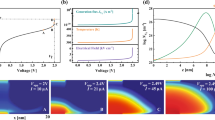

Resistive switching characteristics of AZO/NiO/Pt capacitor structures under negative applied voltage.

(a–c) Current-voltage (I–V) curves of AZO/NiO/Pt structures, in which the NiO buffer layer has a thickness of 12 nm (a), 20 nm (b) and 30 nm (c). Black and red squares reveal the forming characteristics and resistive switching behavior after forming, respectively. Red, green and blue arrows indicate the positions of the 1st-, 2nd- and 3rd-step forming, respectively. The inset of (a) shows a schematic illustration of AZO/NiO/Pt structures with contacts for electrical measurements. (d) Resistance values of AZO/NiO/Pt structures at initial, high resistance and low resistance states, measured at −0.6 V, as functions of the NiO buffer layer thickness. The inset shows the amplitudes of the 1st-, 2nd- and 3rd-step forming voltages of AZO/NiO/Pt structures with different NiO buffer layer thicknesses.

As indicated by the current-voltage (I–V) curves of Figs. 1a–1c, a unipolar RS switching behavior is observed under negative applied voltage in AZO/NiO/Pt structures having NiO layers of thickness equal to 12 nm, 20 nm and 30 nm. Each as-grown structure stays in a high resistance state (HRS). When the applied voltage exceeds the forming voltage (Vforming), the current increases abruptly and the AZO/NiO/Pt structure reaches a low resistance state (LRS). Interestingly, during the forming process, the resistance undergoes a gradual 3-step change (1st-, 2nd- and 3rd-steps are indicated by red, green and blue arrows, respectively). Following the 3-steps forming process, reversible RS behavior occurs at Vreset (LRS → HRS) and Vset (HRS → LRS). Resistances of HRS and LRS during the RS behavior show little dependence on the NiO film thickness (Fig. 1d), although the resistance of the initial state increases with increasing NiO film thickness. In addition, the 2nd-step forming voltage remains constant for all the three AZO/NiO/Pt structures having different NiO film thickness (Inset of Fig. 1d), while the amplitude of the 1st- and 3rd-step forming voltage increases with the NiO film thickness. On the other hand, AZO/NiO/Pt structures under positive applied voltage exhibit typical 1-step forming processes as Pt/NiO/Pt capacitor structures (Supplementary Fig. S1)13,26,27.

Based on the above experimental observations, the 3-stepsforming process (Fig. 2a) can be seen as comprising the following stages: formation of a self-assembly ultra-thin O-rich AZO layer at the AZO/NiO interface and conducting filaments (CFs) in the NiO layer (1st-step); formation of CFs in the self-assembly ultra-thin O-rich AZO layer (2nd-step); irreversible breakdown in the NiO layer (3rd-step). This model for 3-steps forming process in an AZO/NiO/Pt structure is illustrated in Figs. 2b–2f. Under low negative applied bias, O2− ions in the AZO film migrate near the AZO/NiO interface, creating an ultra-thin O-rich AZO layer (Figs. 2b and 2c)28,29,30. At the same time, CFs grow in the NiO film and eventually connect the Pt bottom electrode with the O-rich AZO at the 1st-step forming voltage, which depends on the NiO film thickness (Fig. 2d). The concurrent formation of an ultra-thin O-rich AZO layer at the AZO/NiO interface and CFs in the NiO layer is plausible as the resistance values of the AZO and NiO layers are similar and approximately equal to 10 kΩ. The 1st-step forming process, just like a conventional forming process in a RS material, induces in the NiO layer soft CFs that can be readily broken by applying electrical stress31,32,33. Following the 1st-step, the current flow is limited by the insulating O-rich AZO until CFs are formed in the O-rich AZO at the 2nd-step forming voltage, which is not dependent on the NiO film thickness (Fig. 2e). Finally, further increase of applied bias leads to an irreversible breakdown31,32,33 of the NiO layer at the 3rd-step forming voltage, which depends on the NiO film thickness (Fig. 2f). The 3rd-step forming process, similarly to a hard breakdown, produces in the NiO layer hard CFs that cannot be broken by electrical stress, as their connections are too strong31,32,33. After the 3-stepsforming process, reversible RS behavior seems to occur at the self-assembled ultra-thin O-rich AZO layer whose thickness and characteristics are not affected by the NiO film thickness. In contrast, under positive applied bias, a reversible RS behavior appears in the NiO film after a typical 1-step forming process. Here, O2− ions in the AZO film migrate to the surface of AZO before evolving to oxygen gas and escaping into the atmosphere without formation of an ultra-thin O-rich AZO layer14.

Physical model for the observed 3-steps forming process.

(a) Typical 3-steps forming process observed in AZO/NiO/Pt structures under negative applied voltage. (b–f) Illustration of a physical model for the 3-stepsforming process: formation of a self-assembly ultra-thin O-rich AZO layer at the AZO/NiO interface and conducting filaments (CFs) in the NiO layer (1st-step forming, b–d); formation of CFs in the self-assembly ultra-thin O-rich AZO layer (2nd-step forming, e); irreversible breakdown in the NiO layer (3rd-step forming, f).

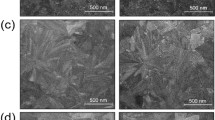

As shown in Figs. 3a and 3b, we confirmed the existence of an amorphous ultra-thin O-rich AZO layer at the AZO/NiO interface via cross-sectional TEM and SIMS depth profile measurements. Three different AZO/NiO/Pt structures were prepared: after forming with negative bias (N-Forming); after forming with positive bias (P-Forming); before forming (pristine). The cross-sectional TEM image of the N-Forming structure clearly shows an amorphous ultra-thin interfacial layer with a thickness of approximately 2–5 nm (left panel in Fig. 3a). Conversely, P-Forming and pristine structures have clean AZO/NiO interfaces without interfacial layers. SIMS depth profile data near the AZO/NiO interface of the N-Forming structure reveal an oxygen content 2.5% higher than that of P-Forming and pristine structures (Fig. 3b). It is worth noting that the thickness of the O-rich area in the expanded SIMS data (Fig. 3c) of the N-Forming structure is estimated to be ca. 3 nm, which is very close to the value obtained via cross-sectional TEM. As a result, we have demonstrated that a self-assembled ultra-thin O-rich layer is indeed formed by FIOM technique.

Experimental evidence of the formation of an ultra-thin O-rich layer by field-induced oxygen migration (FIOM) at the AZO/NiO interface.

(a) Cross-sectional TEM images obtained for three different AZO/NiO/Pt structures: after forming with negative bias (N-Forming, left panel); after forming with positive bias (P-Forming, middle panel); before forming (pristine, right panel). (b and c) SIMS depth-profile data (b) and the expanded one (c) measured for the three different AZO/NiO/Pt structures.

FIOM is a simple method to fabricate ultra-thin oxide layers used as active parts in oxide-based memory devices or as gate insulators in field effect transistor (FET) structures. To prove the general application of FIOM and rule out the effects of the NiO buffer layer, we fabricated AZO/Pt and CZO/Pt structures using the sputtering method and conventional lift-off process (Fig. 4a). As shown in Figs. 4b and 4c, bistable unipolar RS behavior is observed in all the structures after negative forming, while it is not found after applying positive bias. Seemingly, the 1-step forming process under negative bias is likely to occur at an O-rich layer formed at the TCO/Pt interface by FIOM, since TCO and Pt layers are not RS materials. To confirm the formation of the ultra-thin O-rich layer at the CZO/Pt interface, we performed the same cross-sectional TEM measurements carried out for the AZO/NiO/Pt structure. The cross-sectional TEM image of the N-Forming CZO/Pt structure clearly shows the existence of an amorphous ultra-thin interfacial layer with thickness of approximately 3–5 nm, while pristine CZO/Pt structures and post-positive bias samples reveal clean interfaces (Fig. 4d).

Resistive switching characteristics of ultra-thin O-rich layers formed by FIOM in AZO/Pt and CZO/Pt structures.

(a) Schematic illustration of AZO/Pt and CZO/Pt structures with contacts for electrical measurements. (b and c) I–V curves of AZO/Pt (b) and CZO/Pt (c) structures. RS behavior (red squares) is observed after 1-step forming (black squares) only under negative applied voltage. (d) Cross-sectional TEM images of three different CZO/Pt structures: after forming with negative bias (N-forming, left panel); after positive bias (middle panel); pristine (right panel).

Finally, we artificially controlled the concentration of doping metal in a TCO by changing the sputtering condition. As the doping metal concentration increased, the initial resistance of the TCO/Pt structure decreased. Interestingly, TCO/Pt structures with a low initial resistance value showed RS behavior only under negative applied voltage (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2). It seems that a low initial resistance of TCO is a necessary condition for the formation of an ultra-thin O-rich layer by FIOM. It is expected that oxygen ion migration is enhanced in a TCO with low initial resistance, as this induces strong Joule heating leading to a reduction in the activation energy for the migration of oxygen ions28,29,30.

Conclusion

In summary, we propose a new simple method to form an ultra-thin oxide layer using FIOM. The FIOM technique, when applied to an AZO/NiO/Pt structure, can be used to create an O-rich AZO layer with a thickness of ca. 3–5 nm at the AZO/NiO interface. Such an ultra-thin layer exhibits RS behavior, indicating that the FIOM technique is a valuable tool for ReRAM devices whose RS behavior occurs in a very confined region. In fact, RS behavior restricted to a nanosized region is necessary to develop high-density ReRAM devices with reliable RS characteristics. Moreover, the FIOM technique also induces the formation of ultra-thin O-rich layers with RS behavior at the interfaces of AZO/Pt and CZO/Pt structures without the NiO buffer layer. We expect that the FIOM technique will be widely adopted to fabricate ultra-thin oxide layers as active parts in high-density oxide-based memory devices or as gate insulators in FET structures.

Methods

Materials

NiO thin films with thickness of 12 nm, 20 nm and 30 nm were deposited on Pt/Ti/SiO2/Si substrates through the direct-current (DC) sputtering method using a Ni metal target in an argon atmosphere with a 13% oxygen ratio at room temperature. AZO electrodes with 200 nm thickness were fabricated on NiO/Pt or Pt substrates through radio-frequency (RF) sputtering using an AZO ceramic target (doped with 4 wt % Al) in an argon atmosphere at room temperature. CZO electrodes were fabricated on Pt substrates through the co-sputtering method using a Cu metal target and a ZnO ceramic target in an argon atmosphere at room temperature. The Cu doping ratio was controlled by DC sputtering power for Cu (10 W, 20 W and 30 W). ZnO was deposited using RF sputtering with a power of 150 W. TCO electrodes with an area of 50 × 50 μm2 were patterned using the conventional photolithography and lift-off process.

Characterization

The electrical properties of all the ReRAM devices were investigated using current-voltage (I-V) sweep mode at room temperature with a semiconductor parameter analyzer (4156B, Agilent Inc). The chemical composition depth profiles of AZO/NiO/Pt and CZO/Pt structures were acquired using SIMS (CAMECA IMS 7f magnetic sector SIMS) equipped with a sputtering gun that removes a surface layer of 1 nm. TEM cross-sectional images were obtained using a 300 kV field-emission TEM (Tecnai G2 F30 super-twin).

References

Flint, O. & Varley, H. O. Type of ion migration on a metal/metal oxide system. Nature 179, 4551 (1957).

Evans, J. S. O., Hu, Z., Jorgensen, J. D., Argyriou, D. N., Short, S. & Sleight, A. W. Compressibility, phase transitions and oxygen migration in zirconium tungstate, ZrW2O8 . Science 275, 61 (1997).

Valov, I. et al. Nanovatteries in redox-based resistive switches require extension of memristor theory. Nature Comm. 4, 1771 (2013).

Kalabukhov, A., Gunnarsson, R., Börjesson, J., Olsson, E., Claeson, T. & Winkler, D. Effect of oxygen vacancies in the SrTiO3 substrate on the electrical properties of the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interface. Phys. Rev. B 75, 121404 (2007).

Strukov, D. B., Snider, G. S., Stewart, D. R. & Williams, R. S. The missing memristor found. Nature 453, 80 (2008).

Nomura, K., Ohta, H., Takagi, A., Kamiya, T., Hirano, M. & Hosono, H. Room-temperature fabrication of transparent flexible thin-film transistors using amorphous oxide semiconductors. Nature 432, 488 (2004).

Tsukazaki, A. et al. Repeated temperature modulation epitaxy for p-type doping and light-emitting diode based on ZnO. Nature Mater. 4, 42 (2005).

Gratzel, M. Photoelectrochemical cells. Nature 414, 338 (2001).

Kwon, D. -H. et al. Atomic structure of conducting nanofilaments in TiO2 resistive switching memory. Nature nanotech. 5, 148 (2010).

Park, B. H., Kang, B. S., Bu, S. D., Noh, T. W., Lee, J. & Jo, W. Lanthanum-substituted bismuth titanate for use in non-volatile memories. Nature 401, 682 (1999).

Carcia, P. F., Mclean, R. S., Reilly, M. H. & Nunes Jr, G. Transparent ZnO thin-film transistor fabricated by rf magnetron sputtering. Appl. Phys. Lett. 82, 1117 (2003).

Bae, J. et al. Coexistence of bi-stable memory and mono-stable threshold resistance switching phenomena in amorphous NbOx films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 062902 (2012).

Hwang, I. et al. Resistive switching transition induced by a voltage pulse in a Pt/NiO/Pt structure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 052106 (2010).

Szot, K., Speier, W., Bihlmayer, G. & Waser, R. Switching the electrical resistance of individual dislocation in single-crystalline SrTiO3 . Nature Mater. 5, 312 (2006).

Banger, K. K. et al. Low-temperature, high-performance solution-processed metal oxide thin-film trasistor formed by a ‘sol-gel on chip’ process. Nature Mater. 10, 45 (2011).

Cava, R. J., Batlogg, B., Chen, C. H., Rietman, E. A., Zahurak, S. M. & Werder, D. Single-phase 60-K bulk superconductor in annealed Ba2YCu307-δ (0.3 < δ < 0.4) with correlated oxygen vacancies in the Cu-O chains. Phys. Rev. B 36, 5719 (1987).

Bae, Y. C. et al. Oxygen ion drift-induced complementary resistive switching in homo TiOx/TiOy/TiOx and hetero TiOx/TiON/TiOx triple multilayer frameworks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 709-716 (2012).

Lee, M. -J. et al. A plasma-treated chalcogenide switch device for stackable scalable 3D nanoscale memory. Nature Comm. 4, 2629 (2013).

Song, S. et al. Three-dimensional integration of organic resistive memory devices. Adv Mater. 22, 5048–5052 (2010).

Moreno, C., Munuera, C., Valencia, S., Kronast, F., Obradors, X. & Ocal, C. Reversible resistive switching and multilevel recording in La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 thin films for low cost nonvolatile memories. Nano Lett. 10, 3828–3835 (2010).

Hong, S. et al. Large resistive switching in ferroelectctic BiFeO3 Nano-island based switchable diodes. Adv Mater. 25, 2339–2343 (2013).

Nagashima, K. et al. Intrinsic mechanisms of memristive switching. Nano Lett. 11, 2114–2118 (2011).

Jeong, H. Y. et al. Graphene oxide thin films for flexible nonvolatile memory applications. Nano Lett. 10, 4381–4386 (2010).

Lee, M. -J. et al. A fast, high-endurance and scalable non-volatile memory device made from asymmetric Ta2O5-x/TaO2-x bilayer structures. Nature Mater. 10, 625 (2011).

Yanagida, T. et al. Scaling effect on unipolar and bipolar resistive switching of metal oxides. Sci. Rep. 3, 1657 (2013).

Lee, M. -J. et al. Two series oxide resistors applicable to high speed and high density nonvolatile memory. Adv. Mater. 19, 3919–3923 (2007).

Seo, S. et al. Reproducible resistance switching in polycrystalline NiO films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 5655 (2004).

He, L. et al. Memory and threshold resistance switching in Ni/NiO core-shell nanowires. Nano Lett. 11, 4601–4606 (2011).

Strukov, D. B. & Williams, R. S. Exponential ionic drift: fast switching and low volatility of thin-film memristors. Appl. Phys. A 94, 515–519 (2009).

Yang, J. J. et al. The mechanism of electroforming of metal oxide memristive switches. Nanotechnol. 20, 215201 (2009).

Park, G. -. S. et al. Observation of electric-field induced Ni filament channels in polycrystalline NiOx film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 222103 (2007).

Jung, R. et al. Decrease in switching voltage fluctuation of Pt/NiOx/Pt structure by process control. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 022112 (2007).

Kim, D. C. et al. Electrical observations of filamentary conductions for the resistive memory switching in NiO films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 202102 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (No. 2013R1A3A2042120, 2011-0030229 and 2008-0061893 (QMMRC)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L., I.H. and B.H.P. planned the projects and designed the experiments; S.L. and I.H. performed film growth, transport measurements, data analysis and transmission electron microscopy measurements; S.O., Y.N., K.L. and C.Y. assisted in the film growth experiment; S.H. and Y.K. assisted in transport measurements; S.L., I.H., W.K. and B.H.P. performed secondary ion mass spectroscopy measurements and data analysis; S.L., I.H. and B.H.P. interpreted the results; all authors participated in discussion and writing the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, S., Hwang, I., Oh, S. et al. Ultra-thin resistive switching oxide layers self-assembled by field-induced oxygen migration (FIOM) technique. Sci Rep 4, 6871 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06871

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06871

This article is cited by

-

Effect of oxygen vacancy concentration on the resistive random access memory characteristics of NiOx (x = 1, 0.97, 0.94) thin films

Journal of Materials Science (2024)

-

Valence Change Bipolar Resistive Switching Accompanied With Magnetization Switching in CoFe2O4 Thin Film

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Point contact resistive switching memory based on self-formed interface of Al/ITO

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Three-Dimensional Image of Cleavage Bodies in Nuclei Is Configured Using Gas Cluster Ion Beam with Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry

Scientific Reports (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.