Abstract

Tungsten has been chosen as the main candidate for plasma facing components (PFCs) due to its superior properties under extreme operating conditions in future nuclear fusion reactors such as ITER. One of the serious issues for PFCs is the high heat load during transient events such as ELMs and disruption in the reactor. Recrystallization and grain size growth in PFC materials caused by transients are undesirable changes in the material, since the isotropic microstructure developed after recrystallization exhibits a higher ductile-to-brittle transition temperature which increases with the grain size, a lower thermal shock fatigue resistance, a lower mechanical strength and an increased surface roughening. The current work was focused on careful determination of the threshold parameters for surface recrystallization, grain growth rate and thermal shock fatigue resistance under ELM-like transient heat events. Transient heat loads were simulated using long pulse laser beams for two different grades of ultrafine-grained tungsten. It was observed that cold rolled tungsten demonstrated better power handling capabilities and higher thermal stress fatigue resistance compared to severely deformed tungsten. Higher recrystallization threshold, slower grain growth and lower degree of surface roughening were observed in the cold rolled tungsten.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tungsten was selected as the main candidate for plasma facing components (PFCs) in the magnetic confinement nuclear fusion reactors of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), due to its high thermal conductivity1, low tritium retention2,3, low sputtering yield4,5, low erosion rate5,6 and high neutron load capacity7, which all together can result in longer component lifetime8. Tungsten was also proposed as a promising structural material candidate for the Demonstration Power Plant (DEMO) reactor for the high temperature wall operation regime using helium cooled design3.

Significant research efforts were focused on detailed investigations of issues and concerns resulting from plasma-tungsten interactions and the limitations to use tungsten in future fusion reactors. The list of issues includes erosion by energetic ions and neutral atoms from the plasma6, helium bubble formation9, blistering, swelling10, crack formation, tritium retention2 and etc.8. One of the serious issues for PFCs is the heat load accompanied by transient events such as edge-localized-modes (ELMs) and disruptions in the reactor. These transient events lead to a significant temperature rise above the normal operating temperature of the reactor and cause high thermal stresses in PFCs. High temperature gradient and high thermal stresses developed during transients can lead to material recrystallization and grain growth, formation of a melt layer, material erosion and crack formation. Therefore, can limit the power handling capacity of PFCs, decrease their lifetime and lead to plasma contamination that affects subsequent operations. In order to study the effect of ELMs on PFCs, plasma guns4,11,12, quasi-steady-state plasma accelerators13,14, electron beams15,16,17 and long pulse lasers18,19 have been used to simulate transient reactor conditions.

The mechanisms leading to material erosion, crack formation and surface melting under ELMs-like transient heat events in different tungsten grades were investigated in detail by several groups19,20,21,22. However, limited information is available about recrystallization and grain growth processes under ELMs-like transient heat events. Recrystallization and grain size growth in PFC materials can be a critical issue, since the isotropic microstructure developed after recrystallization exhibits a higher ductile-to-brittle transition temperature (DBTT) which increases with the grain size23, a lower thermal shock fatigue resistance, a lower mechanical strength and an increased surface roughening21,22. The goal of this work was to examine the performance of two types of ultrafine-grained tungsten materials to high ELMs-like transient heat events. The use of ultrafine-grained materials as a PFC was of the proposed solutions to mitigate radiation damage due to higher grain boundary area24. Recent research25,26 has investigated such effect. Moreover, ultrafine-grained tungsten was shown to have improved ductility and enhanced mechanical properties27. Such materials, however, have to be examined under high heat loads and temperature stresses relevant to reactor conditions.

In this work, we determine the threshold parameters for surface recrystallization, grain growth rate and thermal shock fatigue resistance under ELM-like transient heat events simulated using long pulse laser beams for two different types of ultrafine-grained tungsten (severely deformed tungsten and cold rolled tungsten). In order to determine the threshold parameters, surface modification and grain size evolution after recrystallization with increasing heat flux parameter, we conducted the power scan experiment with surface power density ranging from 0.49 GW/m2 to 1.5 GW/m2. Surface modification, grain size evolution and thermal shock fatigue resistance under repetitive transient heat events were investigated in the pulse number experiment with the number of laser pulses increasing from 1 up to 1000 at the fixed power density.

Results

In order to investigate the material response to thermal loading using laser pulses, two different schemes of experiments were performed, viz. power scan and pulse number scan. In the power scan experiment the power density at the target surface is varied from 0.49 GW/m2 to 1.5 GW/m2 and the target is exposed to 100 pulses. Heat loads were expressed using heat load parameter F = P√tP, which is directly proportional to the surface power load multiplied by square root of pulse duration. The corresponding changes in the heat flux are from 15.4 to 46.2 MJ/m2s1/2. In the pulse number scan experiment, the heat flux parameter was fixed at 35.7 MJ/m2s1/2, with the number of pulses varied from 1–1000.

Starting microstructures

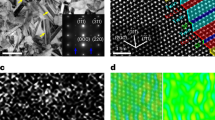

The microstructure of the severely deformed tungsten by chip formation is summarized in Fig. 1. The TEM image, shown in Fig. 1(a) clearly shows the highly refined structure in this sample; grains as small as 50 nm can also be seen. The inset to Fig. 1(a) shows the diffraction pattern from the area in the image; the arc shaped patterns are indicative of the preferred crystallographic (texture) in the sample. The cross-sectional SEM images in Fig. 1(b) demonstrates that the grains in the severely deformed tungsten before laser-induced recrystallization were elongated and at an angle of around 45 degrees from the sample surface. The EBSD analysis of the sample surface is shown in Fig. 1(c). The microstructure is primarily comprised of low-angle (<15°) grain boundaries, as evident from the boundary misorientation plot. The pole figures also showed two partial texture fibers: <111> fiber and <110> fiber. These texture components arise as a result of simple shear deformation in machining.

Figure 2 summarizes the cold rolled sample microstructure. Elongated, pancaked microstructure can be seen in Figs. 2(a) and (b). The level of microstructure refinement in this sample is smaller than that seen in the severely deformed sample (Fig. 1). The microstructure in this case can be seen to consist of elongated grains, ~500 nm in width, which are further comprised of dislocation substructures within. The expected deformation strain imposed in these samples is lower compared to severely deformed samples. The diffraction pattern (shown in inset to Fig. 2(a)) shows the single-crystal like, spotted pattern, indicative of low misorientation angles between the grains and a strong texture. Grains in the cold rolled sample before laser irradiation were elongated and parallel to the sample surface (Fig. 2 (b)). As evident from the EBSD analysis (Fig. 2(c)), the microstructure indeed consisted of a large fraction (~0.4) of low-angle boundaries, similar to that observed in the severely deformed sample. The pole figures showed that the predominant texture component is the {001}<110> fiber. This fiber is commonly referred to as the α-fiber and results due to the plane-strain compression deformation during the rolling process.

Recrystallization

From the SEM and EBSD observations of the laser spots on the samples surface, the recrystallization heat flux threshold was found to be 15.4 MJ/m2s1/2 for the severely deformed tungsten samples and 24.7 MJ/m2s1/2 for the cold rolled tungsten ones. Figure 3 shows the recrystallized microstructures of the severely deformed and cold rolled samples at these heat fluxes. As seen from the EBSD images, the microstructure transforms into equiaxed type, accompanied with increase in the fraction of high-angle grain boundaries. Numerical analysis based on the 1-D diffusion model described elsewhere was used to estimate the laser induced heating at the sample surface at different fluxes28. The calculated temperature for recrystallization was found to be around 1000°C for the severely deformed tungsten and around 1550°C for the cold rolled tungsten. The lower recrystallization threshold heat flux parameter for the severely deformed tungsten is most likely due to the higher rate of recovery caused by higher dislocation density and stored energy. Meyers and co-workers29 have shown that the dynamic recovery/recrystallization during high rate deformation occurs via dislocation rearrangement into cells. Further accumulation of dislocations at the cell boundary increases the misorientation angle, finally resulting in a recrystallized structure with high angle grain boundaries. It is likely a similar mechanism is responsible for the microstructural transformations observed here considering the thermal and pressure gradients due to the Gaussian nature of the laser shots and the corresponding generated stresses30. Beyond the threshold heat flux, the recrystallized grain size was found to increase with the power load, as well as the number of pulses.

Grain growth during power scan experiment

Figure 4 shows the grain size evolution with increasing power density. It was observed for both types of tungsten samples that the grain size decreases radially from the recrystallized center outward, following the thermal gradient. The difference in grain sizes becomes more noticeable at higher heat fluxes. The corresponding grain sizes in the center and the edge of the irradiation spot are shown in the figure. The dashed lines show the average grain size trend. As seen in the figure, the average grain size of the severely deformed tungsten sample is larger than that of the cold rolled sample. Moreover, the grain size for the severely deformed tungsten sample seems to level off at higher power fluxes when surface melting occurs, whereas the grain size of the cold rolled sample continues to rise steadily without any sign of melting. Surface melting and crack formation was observed in severely deformed tungsten at heat fluxes above F = 36.3 MJ/m2s1/2. Formation of the fairly large, roughly equiaxed, cellular grains during solidification indicates rapid cooling of the material typical for e-beam or laser welding31. The grain sizes of the re-solidified material in the center of the laser spot at the heat flux parameters above surface melting threshold for the severely deformed tungsten seems to depend less on the power load than the grain sizes in the recrystallized material. The size of the grains developed in the re-solidified tungsten is determined by the surface temperature, the cooling rate, nucleation rate and grain growth rate, base pressure and material purity32,33. Surface melting and micro-scale cracks formation observed in the severely deformed tungsten at high heat flux parameters can significantly affect the power distribution over the exposed area and likely affect the average grain size in these samples. For example, the grains outside the molten pool and the cracks remain small even under increasing heat flux because of increased energy absorption in the molten pool/cracked regions. The grain size trend of the severely deformed tungsten was similar to that of van Eden34 (shown in the figure). However, the average grain sizes reported by them were slightly higher. This likely due to the differences in the starting microstructure.

Overall, a much faster grain size growth is observed in the severely deformed tungsten samples for heat fluxes ranging between F = 15.4 MJ/m2s1/2 (recrystallization threshold) and F = 36.3 MJ/m2s1/2 (melting threshold). This highlights the trade-off between the strength and propensity for recrystallization/grain growth.

Grain size evolution under repeating heat load events

In order to investigate the thermal shock resistance of the samples against repetitive transient heat load events, the number of pulses was varied at a constant heat flux parameter F = 35.7 MJ/m2s1/2, slightly below the melting threshold for the severely deformed tungsten; thus, recrystallization would solely be responsible for the grain growth in both tungsten grades. It is estimated that PFC should sustain 106–107 transients during its lifetime in ITER20. Moreover, some studies had shown that higher ELMs frequency could lead to a lower concentration of tungsten impurities in plasma5,35. Laser pulses at the frequency of 1 Hz were utilized in the current work.

The grain size evolution with the number of laser pulses for both types of tungsten samples is shown in Figure 5. Recrystallization after the first laser pulse was observed for both types of tungsten samples, indicating the extremely short (~millisecond) timescales of the thermally activated transformation processes34. As evident from the figure, the average grain size increases with the number of pulses, accompanied by increasing grain size gradient from the center of the recrystallized region to its edge. The grain size of the severely deformed tungsten is greater than that of the cold rolled sample up to 250 pulses and then seems to level off at increased number of pulses. In contrast, cold rolled tungsten exhibited a continuous grain size growth (albeit with decreasing rate) with the number of laser pulses (up to 1000 pulses). These grain growth characteristics are similar to those observed under increasing heat fluxes. It should be noted that major crack formation was observed in the severely deformed tungsten after 250 pulses and surface melting occurred after 750 pulses. After 250 pulses, cold rolled sample showed surface roughening, but no signs of major crack formation. No surface melting was observed in cold rolled samples even after 1000 laser pulses.

In summary, the propensity for grain growth with increasing power load or repeated pulse events is evidently more in the severely deformed samples compared to the cold rolled samples. Moreover, the cold rolled tungsten samples exhibited a low degree of surface roughening and no surface melting or crack formation, indicating its overall higher thermal shock fatigue resistance.

Surface roughening

Under large power loads or large number of pulse events, significant surface roughening of the recrystallized material has been observed in both the severely deformed and cold rolled samples. This is attributed to the repeated plastic deformation of the sample surface13,22,36. Figures 6 and 7 show this phenomenon in the severely deformed and cold rolled tungsten, respectively. At 100 pulses exposure, appreciable changes in the surfaces morphology were first observed at F = 31.3 MJ/m2s1/2. For the severely deformed tungsten samples, surface melting and cracking occurred when the heat flux parameter exceeded 36.3 MJ/m2s1/2 with a smooth, fully recrystallized surface inside the molten (and solidified) pool and some roughness outside the pool (Fig. 6(b)). The surface roughness outside the molten area increased with increasing power density (Fig. 6(c)). The roughness of the area affected by the laser beam the for cold rolled tungsten samples increased constantly with the power density without producing surface melting or major cracks (Figure 7).

The effect of increasing the number of pulses at a fixed heat flux F = 35.7 MJ/m2s1/2, on surface morphology is shown in Figs. 8 and 9 for severely deformed and cold rolled tungsten, respectively. Surface morphology was altered to a higher degree with increasing number of pulses compared to increased power load. As evident from the figures, considerably faster surface roughening with the number of laser pulses was observed for the severely deformed tungsten compared to the cold rolled tungsten. Moreover, micro-scale cracks and surface melting occurred in the severely deformed tungsten samples at larger number of laser pulses. This observation again suggests the better power handling properties and thermal shock resistance of cold rolled samples compared to severely deformed samples.

Microstructural properties after recrystallization

Microstructural properties of tungsten, such as crystallographic orientation and grain boundary type, affect the mechanical behavior, surface properties and radiation resistance of the material37,38,39. From EBSD micrographs we observed that the misorientation angle distribution drastically changed after recrystallization for both the severely deformed tungsten and the cold rolled tungsten samples. The fraction of low angle grains in pristine samples was around 40–50% for both tungsten grades (Fig. 1(c) and Fig. 2 (c)). A random distribution of the crystallographic orientations was observed in the pristine the severely deformed sample (Fig. 2 (c)). Cold rolled tungsten had grains preferably oriented in the <001> direction (Fig. 1(c)). In the case of severely deformed tungsten, the crystallographic orientation of grains remained random after recrystallization as the power load increased in the power scan experiments and for any number of laser pulses in the pulse number experiment (Figs. 10 and 11). At the same time, for cold rolled tungsten, the <001> direction became preferential again after the nucleation phase for higher power loads and number of pulses (Figs. 12 and 13). We attribute the preferential recrystallization texture developed in cold rolled tungsten to the selected growth of grains preferably oriented with respect to the matrix. Such grains grow faster, absorb other grains40 and have a tendency to restore the initial texture of the matrix. The fraction of grains oriented in the <001> direction increased with grain growth in both power scan and pulse number scan experiments.

EBSD micrographs (IPF maps) and (001) pole figures of severely deformed tungsten samples from the center of the affected region after 100 shots at (a) F = 15.4 MJ/m2s1/2 (scan step size 0.05 μm), (b) 31.3 MJ/m2s1/2 (scan step size 1 μm) and (c) 46.2 MJ/m2s1/2 (scan step size 2.5 μm). Note different scale bars in the images.

EBSD micrographs (IPF maps) and (001) pole figures of severely deformed tungsten sample from the center of the affected region at F = 35.7 MJ/m2s1/2 after (a) 1 shot (scan step size 0.65 μm), (b) 100 shots (scan step size 1 μm) and (c) 250 shots (scan step size 1 μm). Note different scale bars in the images.

EBSD micrographs (IPF maps) and (001) pole figures of cold rolled tungsten sample from the center of the affected region after 100 shots at (a) F = 15.4 MJ/m2s1/2 (scan step size 0.05 μm), (b) 31.3 MJ/m2s1/2 (scan step size 0.33 μm) and (c) 46.2 MJ/m2s1/2 (scan step size 2.8 μm). Note different scale bars in the images.

Discussion

The recrystallization threshold for both tungsten grades was determined in the power scan experiment. Possible reasons for the lower threshold heat flux parameter for severely deformed tungsten are the differences in mechanical properties, defect density, stored energy (strain) and impurities concentration. For both types of samples, the Vickers hardness measurement was performed. The Vickers harnesses of the severely deformed sample and the rolled sample were around 555 Kg/mm2 (5443 MPa) and 525 Kg/mm2 (5149 MPa) respectively, indicating higher hardness and therefore, yield strength (approximating the Vickers hardness to be three times the yield strength)41 for the former. As reported before42, the effective strain in the severely deformed tungsten chips was around 2.1 measured by particle image velocimetry (PIV), thus, these chips have higher stored energy and can undergo recrystallization at lower temperatures than the rolled samples. Recently, El-Atwani et al.26, has reported that the recrystallization of these chips when irradiated with high flux He+ at 1200°C. Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDX) performed on both types of samples after ion beam (Gallium ions) cleaning (not shown here), indicated similar impurity levels (~99.5% pure), eliminating the impurity level factor for the recrystallization threshold difference.

Grain growth was observed above the recrystallization threshold for both tungsten grades with an increase in the power load and the number of laser shots. Higher grain growth rate vs. power density was observed in severely deformed tungsten samples in the power scan experiment for the heat flux parameter ranging from 15.4 MJ/m2s1/2 to 36.3 MJ/m2s1/2 below melting threshold for the samples. In the pulse number scan experiment, larger grains were observed in the severely deformed tungsten samples up to 500 shots from which the cold rolled tungsten started to have larger grains. This is attributed to crack formation in the severely deformed tungsten samples after 250 shots before which the maximum grain size is observed (Fig. 5). Large cracks could alter the power distribution (absorbing energy during crack propagation) and affect grain size distribution. However, from the evolution of sample surface morphology in both experiments, we concluded that cold rolled tungsten demonstrated considerably better power handling capabilities and thermal shock fatigue resistance.

The superior characteristics of cold rolled tungsten were reattributed to the difference in macro- and micro- properties of the two tungsten grades, such as preferential crystallographic orientation restored in cold rolled tungsten after recrystallization and preferential special orientation of the grains parallel to the specimen surface in the pristine sample. The effect of special orientation of grains on the material behavior under transient heat events is well-studied21,36,43. Moreover, it is known that strong texture inhibit grain growth44,45. Assuming grain boundary migration is limited to grain boundary diffusion, grains of similar orientation (low-angle boundaries) would migrate slower than grains of large misorientation (large-angle grain boundaries). Figures 12 and 13 show strong texture of the recrystallized rolled samples explaining the slower grain growth than the severely deformed tungsten samples (Figs. 10 and 11).

Recrystallization texture could be explained by two theories: oriented growth and oriented nucleation46. In oriented nucleation theory explained by Burgers47, grains of certain orientation dictates texture which forms due to large number of crystals nucleated in preferred orientation. In growth oriented theory explained by Beck and Hu48, the nucleated crystals could be random but the texture is dictated by large crystals formed due to selective growth rates. Figure 12 (a) shows the initial recrystallization process of the cold rolled sample. No large number of preferred oriented crystals is observed which could indicate that the preferred texture formed on the cold rolled samples follows oriented growth theory.

Moreover, preferential crystallographic orientation of the cold rolled tungsten grade after recrystallization was expected to affect the properties of the material. It is commonly known that materials with preferential crystallographic orientation or single crystals exhibit anisotropy in their mechanical, thermal and other properties23. Subhash et al.49 reported that <001> single crystal tungsten exhibits higher ductility and flow stress compared to <011> single crystal and fine-grained polycrystalline samples. Makhankov et al.37 compared different polycrystalline tungsten grades and single crystal tungsten (<110> and <111> directions) under fusion relevant power loads simulated with a pulsed electron beam. The strong dependence of the material resistance to high heat fluxes on the orientation of the tungsten grains was reported. According to the authors, no intense surface crack formation or severe surface damage was observed in the single crystal tungsten after disruption simulations and thermal fatigue loading. These superior properties of single crystal tungsten were credited to its higher ductility and absence of grain boundaries37. The effect of preferential crystallographic orientation on power handling capability and thermal shock fatigue resistance under repetitive transient heat events of the cold rolled tungsten sample due to anisotropy of material properties requires further investigation.

Methods

Materials

Two starting ultrafine-grained microstructures of pure tungsten were considered for the study, because of their high-strength characteristics. Since the microstructures were comprised of highly elongated grains, the smallest distance between the grain boundaries was taken as the grain size. Herein, the samples having grain sizes in the 100–500 nm are defined ultrafine-grained (UFG) and those below 100 nm as nanocrystalline. Nanocrystalline samples were processed using severe plastic deformation (SPD) involved in chip formation in machining. The UFG severely deformed tungsten samples were processed using orthogonal machining process which is detailed elsewhere42,50. The UFG samples, processed using cold rolling, were provided by Alfa Aesar. Samples were mechanically polished to a final roughness of <1 μm for the laser experiments.

Experimental setup

A long pulse neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (NdYAG) laser (GSI Lumonics) operating at 1064 nm and at 1 Hz repetition rate with a pulse width of 1 ± 0.1 ms was used to simulate the transient heat load events on the samples. All the experiments were performed at the base pressure ~ 10−5 Torr in a high vacuum chamber. To provide the same experimental conditions for each shot during the power load scan experiments, as well as during the pulse number scan experiments, all or most of the shots were done on the same target mounted on an XY translational stage. All the experimental runs were carried out at room temperature. The laser beam was allowed to pass through a window of the chamber and focused perpendicularly on the sample surface using a focusing lens (f = 40 cm) with a spot diameter of ~1 mm.

Materials characterization

For analyzing the surface modification, microstructure and grain size high resolution scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed using a Hitachi S4800 FESEM. Cross-sectional imaging was performed using an FEI Nova 200 NanoLab Dual Beam Focused ion beam/scanning electron microscope (FIB/SEM). The average grain size was determined using the intercept length method, covering at least 500 grains. Local crystallographic texture and grain boundary misorientation was acquired using electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) on FEI XL-40 scanning electron microscope. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) characterization of the samples was performed using FEI-Tecnai 80/200 LaB6 TEM. The TEM samples were prepared using the twin-jet electropolishing technique with a 0.5% NaOH – water solution at RT.

Change history

12 March 2015

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

References

Davis, J., Barabash, V., Makhankov, A., Plochl, L. & Slattery, K. Assessment of tungsten for use in the ITER plasma facing components. J. Nucl. Mater. 258, 308–312 (1998).

Causey, R., Wilson, K., Venhaus, T. & Wampler, W. Tritium retention in tungsten exposed to intense fluxes of 100 eV tritons. J. Nucl. Mater. 266, 467–471 (1999).

Philipps, V. Tungsten as material for plasma-facing components in fusion devices. J. Nucl. Mater. 415, S2–S9 (2011).

Federici, G. et al. Effects of ELMS and disruptions on ITER divertor armour materials. J. Nucl. Mater. 337, 684–690 (2005).

Neu, R. et al. Tungsten: an option for divertor and main chamber plasma facing components in future fusion devices. Nucl. Fusion 45, 209–218 (2005).

Bolt, H. et al. Materials for the plasma-facing components of fusion reactors. J. Nucl. Mater. 329, 66–73 (2004).

Fukuda, M., Hasegawa, A., Tanno, T., Nogami, S. & Kurishita, H. Property change of advanced tungsten alloys due to neutron irradiation. J. Nucl. Mater. 442, S273–S276 (2013).

Rieth, M. & Dudarev, S. L. Recent progress in research on tungsten materials for nuclear fusion applications in Europe. J. Nucl. Mater. 432, 482–500 (2013).

Sharafat, S., Takahashi, A., Nagasawa, K. & Ghoniem, N. A description of stress driven bubble growth of helium implanted tungsten. J. Nucl. Mater. 389, 203–212 (2009).

Iwakiri, H., Yasunaga, K., Morishita, K. & Yoshida, N. Microstructure evolution in tungsten during low-energy helium ion irradiation. J. Nucl. Mater. 283, 1134–1138 (2000).

Klimov, N. et al. Experimental study of PFCs erosion and eroded material deposition under ITER-like transient loads at the plasma gun facility QSPA-T. J. Nucl. Mater. 415, S59–S64 (2011).

Zhitlukhin, A. et al. Effects of ELMS on ITER divertor armour materials. J. Nucl. Mater. 363, 301–307 (2007).

Garkusha, I. et al. Tungsten erosion under plasma heat loads typical for ITER type I ELMS and disruptions. J. Nucl. Mater. 337, 707–711 (2005).

Pestchanyi, S. & Linke, J. Simulation of cracks in tungsten under ITER specific transient heat loads. Fusion Eng. and Design 82, 1657–1663 (2007).

Pintsuk, G., Kuhnlein, W., Linke, J. & Rodig, M. Investigation of tungsten and beryllium behaviour under short transient events. Fusion Eng. and Design 82, 1720–1729 (2007).

Linke, J. et al. High heat flux simulation experiments with improved electron beam diagnostics. J. Nucl. Mater. 283, 1152–1156 (2000).

Hirai, T., Pintsuk, G., Linke, J. & Batilliot, M. Cracking failure study of ITER-reference tungsten grade under single pulse thermal shock loads at elevated temperatures. J. Nucl. Mater. 390–91, 751–754 (2009).

Yu, J. et al. ITER-relevant transient heat loads on tungsten exposed to plasma and beryllium. Phys. Scr. T159, 014036 (2014).

Kajita, S. et al. Sub-ms laser pulse irradiation on tungsten target damaged by exposure to helium plasma. Nucl. Fusion 47, 1358–1366 (2007).

Arzhannikov, A. et al. Surface modification and droplet formation of tungsten under hot plasma irradiation at the GOL-3. J. Nucl. Mater. 438, S677–S680 (2013).

Pintsuk, G. & Loewenhoff, T. Impact of microstructure on the plasma performance of industrial and high-end tungsten grades. J. Nucl. Mater. 438, S945–S948 (2013).

Wirtz, M., Cempura, G., Linke, J., Pintsuk, G. & Uytdenhouwen, I. Thermal shock response of deformed and recrystallised tungsten. Fusion Eng. and Design 88, 1768–1772 (2013).

Tietz, T. E. & Wilson, J. W. Behavior and Properties of Refractory Metals (Stanford, Stanford University Press, 1965).

Federici, G. et al. Plasma-material interactions in current tokamaks and their implications for next step fusion reactors. Nucl. Fusion 41, 1967 (2001).

El-Atwani, O. et al. In-situ TEM observation of the response of ultrafine- and nanocrystalline-grained tungsten to extreme irradiation environments. Sci. Rep. 4, 1–7 (2014).

El-Atwani, O. et al. Ultrafine tungsten as a plasma-facing component in fusion devices: effect of high flux, high fluence low energy helium irradiation. Nucl. Fusion 54, 083013 (2014).

Wei, Q. et al. Mechanical behavior and dynamic failure of high-strength ultrafine grained tungsten under uniaxial compression. Acta Mater. 54, 77–87 (2006).

Hirai, T. & Pintsuk, G. Thermo-mechanical calculations on operation temperature limits of tungsten as plasma facing material. Fusion Eng. and Design 82, 389–393 (2007).

Meyers, M. A., Nesterenko, V. F., LaSalvia, J. C. & Xue, Q. Shear localization in dynamic deformation of materials: microstructural evolution and self-organization. Mater. Sci. and Eng. a-Structural Mater. Properties Microstructure and Processing 317, 204–225 (2001).

Farid, N., Harilal, S., El-Atwani, O., Ding, H. & Hassanein, A. Experimental simulation of materials degradation of plasma-facing components using lasers. Nucl. Fusion 54, 12002–12008 (2014).

Colvin, J. D., Reed, B. W., Jankowski, A. F. & Kumar, M. Microstructure morphology of shock-induced melt and rapid resolidification in bismuth. J. Appl. Phys. 101, 084906 (2007).

Schaefer, R. J. & Mehrabian, R. Processing/Microstructure Relationships in Surface Melting. MRS 13, 733 (1982).

Savage, S. J. & Froes, F. H. Production of rapidly solidified metals and alloys. JOM 36, 20–33 (1984).

Eden, G. G. Transient heat load studies on tungsten using a pulsed millisecond laser in a high flux plasma enviroment. Master thesis, Utrecht University, (2013).

Dux, R. Chapter 11: Impurity transport in ASDEX upgrade. Fusion Sci. and Tech. 44, 708–715 (2003).

Zhang, X. X. & Yan, Q. Z. The thermal crack characteristics of rolled tungsten in different orientations. J. Nucl. Mater. 444, 428–434 (2014).

Makhankov, A., Barabash, V., Mazul, I. & Youchison, D. Performance of the different tungsten grades under fusion relevant power loads. J. Nucl. Mater. 290, 1117–1122 (2001).

Zhou, Z. J. et al. Transient high heat load tests on pure ultra-fine grained tungsten fabricated by resistance sintering under ultra-high pressure. Fusion Eng. and Design 85, 115–121 (2010).

El-Atwani, O. Ion Beam Irradiation on Hard Materials Surfaces: Nanopatterning of Galium Antimonade and Silicon substrates and Irradiation Damage of Ultrafine and Multimodal Tungsten. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Purdue University, (2013).

Dillamore, I. L. & Roberts, W. T. Preferred orientation in wrought and annealed metals. Metall. Rev. 10, 271–380 (1965).

Tabor, D. The hardness of metals (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1951).

Efe, M., El-Atwani, O., Guo, Y. & Klenosky, D. Microstructure refinement of tungsten by surface deformation for irradiation damage resistance. Scr. Mater. 70, 31–34 (2014).

Pintsuk, G. et al. Thermal shock response of fine- and ultra-fine-grained tungsten-based materials. Phys. Scr. T145, 014060 (2011).

Beck, P. A., Holzworth, M. L. & Sperry, P. R. Effect of a dispersed phase on grain growth in Al-Mn alloys. Trans. Am. Inst. Min. Metall. Eng. 180, 163–192 (1949).

Dunn, C. G. & Walter, J. L. Secondary recrystallization. Recrystallization, grain growth and textures, American Society for Metals, Metals Park, OH, 461–521 (1965).

Deards, N. Recrystallization nucleation and microtexture development in aluminium-iron rolled alloys. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, University of Cambridge, (1992).

Burgers, W. G. Handbuch der Metallphysik (Akad. Verl., 1941).

Beck, P. A. & Hu, H. The origin of recrystalization textures. Recrystallization, grain growth and textures, American Society for Metals, Metals Park, OH, 393–433 (1966).

Subhash, G., Lee, Y. & Ravichndran, G. Plastic deformation of CVD textured tungsten. 1. Constitutive response. Acta Metall. Et Mater. 42, 319–330 (1994).

El-Atwani, O., Efe, M., Heim, B. & Allain, J. Surface damage in ultrafine and multimodal grained tungsten materials induced by low energy helium irradiation. J. Nucl. Mater. 434, 170–177 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), PIRE project and the U.S. DOE, Office of Fusion Energy Sciences (OFES)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The experimental set-up was designed by A.S., O.E., S.H. and A.H. The samples were prepared by A.S. and O.E. The experiments were conducted by A.S.. Characterization of the samples was performed by A.S., O.E. and D.S. Data analysis was made by A.S. with consult from O.E. and S.H. All authors discussed the results. Manuscript was written by A.S. and O.E. with improvements from all authors.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Suslova, A., El-Atwani, O., Sagapuram, D. et al. Recrystallization and grain growth induced by ELMs-like transient heat loads in deformed tungsten samples. Sci Rep 4, 6845 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06845

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06845

This article is cited by

-

Physics and Technology Research for Liquid-Metal Divertor Development, Focused on a Tin-Capillary Porous System Solution, at the OLMAT High Heat-Flux Facility

Journal of Fusion Energy (2023)

-

Novel concept suppressing plasma heat pulses in a tokamak by fast divertor sweeping

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Assessment of hardening due to non-coherent precipitates in tungsten-rhenium alloys at the atomic scale

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Melt layer erosion during ELM-like heat loading on molybdenum as an alternative plasma-facing material

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Extraordinary high ductility/strength of the interface designed bulk W-ZrC alloy plate at relatively low temperature

Scientific Reports (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.