Abstract

When a single molecule is detected in a wide-field microscope, the image approximates the point spread function of the system. However, as the distribution of molecules becomes denser and their images begin to overlap, existing solutions to determine the number of molecules present and their precise three-dimensional locations can tolerate little to no overlap. We propose a localization scheme that can identify several overlapping molecule images while maintaining high localization precision. A solution to this problem involving matched optical and digital techniques, as here proposed, can substantially increase the allowable labeling density and accelerate the data collection time of single-molecule localization microscopy by more than one order of magnitude.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In single-molecule localization microscopy1,2,3, sparse sets of emitters are localized by identifying well separated single-molecule images and fitting them to high precision, thereby achieving resolution better than the diffraction limit. Similar problems appear in many biological and biophysical experiments where two or more molecules need to be resolved or their distance estimated4,5,6. Localization precision can be much better than the diffraction limit, depending on the number of photons detected from the emitter and noise conditions7. Lately, photoswitching, photoactivation and other mechanisms were proposed and developed to overcome the problem of overlapping molecule images in a time sequential form1,2,3,8. The trade-off for super-resolution in these methods is a slower acquisition rate—typically, tens of thousands of frames are collected and processed to generate a single super-resolution image. To ameliorate this problem, researchers have proposed fitting schemes that allow for a few emitters generating overlapping images9,10,11,12,13. Unfortunately, all methods reported so far are limited to two-dimensional imaging9,10,11,12 or provide a modest increase in emitter density13. A related technique based on statistical fluctuation of emitters, SOFI14, provides moderately super-resolved images15. However, SOFI does not provide the locations of individual molecules or convey three-dimensional (3D) information without scanning.

Three-dimensional information is required for complete understanding of many biological structures and phenomena. However, 3D localization microscopy suffers from poor temporal resolution. The ability to obtain 3D localization information from dense molecule arrays could enable faster data acquisition and addresses a fundamental problem in 3D imaging. In this report, we propose and investigate methods to increase the allowable labeling density, namely finding the number and 3D locations of clustered emitters from a single image. The experimental demonstration of the technique in biological samples opens up new opportunities to acquire quantitative information about single molecules and other emitters that remain unresolved in three dimensions with conventional methods. We use microtubules to demonstrate the method's ability to measure the full 3D shape of intracellular structures. In particular, we measure the radius of an antibody labeled microtubule while detecting only about 600 photons per emitter. The methods also enable faster acquisition times for 3D single-molecule localization microscopy, which is critical for live-cell super-resolution imaging. Furthermore, the technique is applicable in other areas such as tracking of multiple particles or 3D surface characterization.

Results

Theory

In what follows we emphasize the distinction between the image generated by an emitter, such as a single-molecule and the point spread function (PSF). While the former depends on the emission pattern of the emitter, noise, sample induced aberrations and the detector array, the latter is only a function of the optical imaging system.

The key observation behind the methods proposed here is the fact that raw images in single-molecule localization microscopy are a combination of sparse (possibly overlapping) molecule images and noise from different sources. This raw image can be efficiently represented with a dictionary consisting of the images of transversely and longitudinally shifted point emitters. A dictionary is a set of vectors that spans the space of possible images. In addition, the 3D PSF can be engineered to facilitate the resolution of dense emitters.

Dictionaries provide alternate representations to the pixel-based image; i.e. a set of coefficients describing the degree to which each dictionary element is present in the image. Interestingly, a scene that appears dense to our eyes (contains numerous overlapping images) may be sparse in a properly chosen dictionary. Sparse means the image can be expressed by a number of coefficients K that is significantly smaller than the number of pixels used in the scene N (K ≪ N). We note that the most efficient representation of a scene with overlapping single-molecule images contains a single coefficient for each emitter in the scene. Since each coefficient in the solution corresponds to an emitter, they are intrinsically resolved and the coefficients are easily converted to locations and photon counts.

The method for resolving and localizing 3D clusters of single molecules involves a combination of optical and digital techniques: (a) Imaging the sample with a proper 3D PSF imaging system; (b) Creating a model of the system via experimental measurements, theoretical calculations, or a combination of both; (c) Establishing a dictionary composed of the image of a point source for different locations in a dense 3D grid; (d) Solving the estimation problem of determining the coefficients of the dictionary elements that best represent the data. Once the non-zero coefficients are known, the number of molecules and their locations and brightnesses can be determined.

Several techniques can encode depth information onto a two-dimensional image by utilizing an engineered PSF16,17,18. Without losing generality, we chose the double-helix (DH) PSF because of its inherent precision and depth of field advantages18. Accordingly, a single emitter in the focal plane generates an image with two horizontally displaced lobes. The transverse location of the emitter is related to the center of the two lobes and the axial location is encoded in the orientation of the lobes19. For illustration, a few dictionary elements for a DH-PSF system are shown in Fig. 1. Each dictionary element contains the 2D cross-section of the PSF corresponding to a different discrete emitter location in the full 3D space. Note that the methods demonstrated here can be applied to any 3D PSF and are not limited to the DH-PSF. However, the particular PSF structure can become a significant factor in the overall performance. The Supplementary Information presents a demonstration of these methods with an astigmatic PSF and a comparison with the DH-PSF.

The most important design parameter for a dictionary is the step size between adjacent elements. Small step sizes are desirable so that the localization precision is not limited by step size. Conversely, smaller steps require more elements, hence a more computationally intensive reconstruction. Typical imaging system designs and desired localization precision necessitate sub-pixel steps. Furthermore, the dictionary extends along the axial direction. These two factors mean we require dictionaries that are overcomplete, i.e. there are more elements D in the dictionary than there are pixels per image (D > N).

To solve the coefficient estimation problem, we investigate two methods that are representative of large classes of solvers. The first method is Matching Pursuit (MP). In MP, an iteration consists of projecting the image onto the dictionary, finding and storing the largest coefficient and subtracting that element from the image20. Iterations continue until a stopping criterion is met. The second method uses Convex Optimization (CO)21. The reconstruction problem is formulated as a convex problem in which the variable to be optimized is the sparsity of the coefficient vector (quantified as the L1 norm). Convex optimization attempts to arrive at a solution for the significant coefficients in parallel. See the methods section for a thorough description of the estimation techniques.

Monte Carlo Simulations

To demonstrate the performance of the two methods, we present the results of Monte Carlo simulations. Increasing numbers of emitters are placed randomly within a volume and reconstructions with MP and CO are compared. When making comparisons, we quantify the accuracy of the number of returned emitters and also their locations. To match our experimental system, the effective pixel size in sample space is 160 nm, which is due to the use of a 100× objective with a Numerical Aperture (NA) of 1.45 and a camera with 16 µm pixel size. The emission wavelength is 670 nm. To reflect typical experimental conditions, each emitter is assumed to produce between 1900 and 2000 detected photons. Noise is simulated by adding a constant background of 20 photons per pixel and Poissonian shot noise is also included. For eight different emitter densities, we simulate three frames of sample volumes that map to an image 47 × 47 pixels on a side. We process these frames using CO and MP and quantify the results in terms of the number of emitters that are correctly localized and the accuracy to which they are localized in each dimension. A graphical summary is shown in Fig. 2.

Performance of different super-resolution methods as a function of the molecule density evaluated via Monte Carlo simulations.

For each density, three simulated frames with a size of 55 µm2 were generated. Then, the results from Matching Pursuit (MP) and Convex Optimization (CO) are quantified and compared to 3D-DAOSTORM (3DDS) (data from13). (a) shows the number of correctly localized emitters. This plot shows that CO can recover the highest molecule density. The localization error is shown in (b–d) for transverse (x,y) and axial(z) localization, respectively. These plots demonstrate it is possible to maintain good localization precision, even at very high densities. For MP, the dictionary had 10 nm transverse step sizes and 15 nm axial steps. The dictionary for CO had 80 nm and 120 nm steps in the transverse and axial dimensions, respectively.

For MP, the dictionary step size is 10 nm in the transverse dimensions and 15 nm in depth, yielding 1.27 million dictionary elements. Even with such a large dictionary, one MP solution on an 11 × 11 window can be completed in tenths of a second on a desktop computer. If the reconstruction returns the correct elements, there will still be localization errors due to the quantization of the solution space. For this dictionary, the standard deviation of the quantization error will be 2.9 nm in each transverse dimension and 4.3 nm axially. The quantization error bounds indicate the error if the correct dictionary element is chosen every time. In the simulations, MP does not perform to the limit of the dictionary. The source of the non-ideal performance of MP is likely due to the so-called “greedy” nature of the algorithm; namely, with each iteration, the largest possible portion of the image is subtracted. This drawback is easily offset by using a finer dictionary. The density of correctly localized emitters (herein named the “recovered density”) can be as high as 1 emitter/µm2, which is twice the maximum recalled density of 3D-DAOSTORM with an astigmatic PSF13. More importantly, this recovered molecule density is more than seven times higher than existing 3D methods, including DH-PSF, astigmatic and bi-plane techniques.

Due to current computational limitations, the dictionary for CO cannot be as large because it is a much more computationally intensive algorithm. Thus, we select a coarser dictionary with transverse steps of 80 nm and axial steps of 120 nm (2904 elements). The effect of quantization error for this dictionary is 23 nm in the transverse dimensions and 35 nm axially. The simulations in Fig. 2 indicate CO performs very close to the limit of the dictionary. Even with such a significantly smaller dictionary, CO still requires an order of magnitude more computation time than MP with a finer dictionary (see the Supplementary Information for more details regarding the calculation time of the algorithms). However, CO performs better than MP in terms of recoverable density. The enhancement enables the reconstruction of frames with an emitter density of more than 1.5 emitters/µm2, which is a three-fold improvement in recoverable density over 3D-DAOSTORM13 and more than an order of magnitude improvement over established 3D localization schemes (DH-PSF, astigmatic and bi-plane).

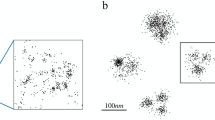

The simulated images in Fig. 3 exemplify the degree to which molecule density is increased to accelerate 3D localization microscopy. Previous localization methods required completely isolated single molecule images, with even nearby emitters causing errors. By enabling the localization algorithm to reconstruct an image with a ten-fold increase in the number of emitters per frame, single molecule microscopy can be accelerated proportionally.

Examples of sparse reconstructions for different density levels.

In both simulated images, we randomly placed emitters in the simulation space and we applied our localization method. The resulting locations are marked as x's. In (a), the recovered density is 0.12 emitters/µm2, which is approximately the limit of existing localization schemes for the DH-PSF. The recovered density in (b) is an order of magnitude higher. This increased recoverable density means 3D super-resolution imaging experiments can now be performed in 1/10th the time. In these images, system parameters were matched to experimental conditions, as discussed later in the article.

The Monte Carlo simulations show that while MP is fast, the results are suboptimal. Conversely, the reconstruction obtained with CO is slower, but the returned locations achieve the limit imposed by the fineness of the dictionary. To attain a method that is fast, accurate and precise we developed a hybrid algorithm that takes advantage of the strengths of both methods. First, MP provides a rough estimate of the number of emitters and their locations. Since the precise location is not needed at this stage, we use a coarse dictionary. Next, CO provides a finer estimation with a refined dictionary. Interestingly, because coarse estimates of the locations are already available from the MP method, we can limit the dictionary to only include elements located close to those estimates. Therefore, we implement a dictionary with the desired fineness while the problem is still computationally tractable. This hybrid algorithm reduces the size of the fine dictionary by nearly two orders of magnitude, enabling CO to be performed in a reasonable time. We refer to this technique as “MP+CO.” At very high densities, MP recalls far fewer sources than CO. In such cases, we have used a CO+CO method, which consists of two or more steps of CO with progressively finer dictionaries. If one were to use MP+CO for very high densities, the initial round of MP might eliminate dictionary elements that are required for the solution. In such cases, the increased computational cost of an additional round of coarse CO is justified.

Experiment

Two examples of experimental scenes (raw data) of dense molecule clusters are shown in Fig. 4. These images are acquired using a SPINDLE system22 incorporating a DH-PSF and stochastic optical reconstruction using photoswitchable dyes2. In the scene in Fig. 4 (a), there are two bright lobes, with a third dim lobe nearby. There are likely two emitters; one bright emitter and a dim emitter nearby with one lobe coinciding with a lobe of the bright emitter. The hybrid method is able to identify the individual emitters despite the overlap of the lobes. The scene in Fig. 4 (d) is even more complex. MP+CO is able to resolve and localize three emitters in this scene. Such a scene would be rejected from typical localization algorithms and none of the emitters would contribute to the final image.

Experimental demonstration of 3D super-resolution and super-localization from overlapping single-molecule images.

(a) and (d) Two examples of raw data of overlapping molecule images using a DH-PSF system. (b) and (e) show the estimated locations of the molecules using the MP and hybrid methods. The regions used for the refined dictionary are marked with blue cubic boxes. The images in (c) and (f) show the reconstructed image using MP+CO. In all images, scale bars are 1 µm.

An example application in a large-scale super-resolution image is shown in part (b) of Fig. 5. For comparison, a standard fluorescence image is shown in part (a) of the same figure. The sample is composed of PtK1 cells (Rat Kangaroo Epithelial cells) in which tubulin is labeled with Alexa-647 and Alexa-488 dyes. The reconstruction image was compiled from more than 30,000 frames and the image clearly demonstrates 3D super-resolution capabilities. In the standard fluorescence image of this scene, many of the individual microtubules either cannot be resolved or are out of focus due to the limited depth of focus of the standard PSF of high-NA objectives.

Large-scale experimental implementation.

A standard fluorescence image is shown in (a). The 3D super-resolution image (b) of labeled tubulin in PtK1 cells demonstrates that the method can be applied to localization-based super-resolution imaging with a wide field of view. The small box on the right side of (b) indicates the region that is used for subsequent detailed analysis. Scale bar: 1 µm.

The super-resolution image in Fig. 5 (b) was generated by assigning a Gaussian spot to each localized emitter. The width of the Gaussian is inversely related to the square root of the number of photons received by the emitter (a higher photon count means the Cramer-Rao bound is lower, i.e. the localization precision is better). The color of the spot is determined by the depth of the emitter.

Although simulations already indicate these sparsity-based methods can allow high label densities without sacrificing the ability to achieve super-resolution, we also evaluated the performance on experimental data. Fig. 6 (a) shows a small region of the super-resolution image from Fig. 5. As opposed to the prior image, here the localizations are visualized in a scatter plot, although depth is indicated with color as before. The set of 131 locations was fit to a straight line in 3D space (see the Supplementary Information for an analysis of the 3D sampling of this structure). These points were then converted to a 2D space which defines the transverse and axial distance from the fit line to each point. Here, “axial” is referring to the optical axis of the microscope. This view is shown in Fig. 6 (b). Equivalently, one can think of this as a view of the 3D cloud of points from a position along the microtubule. The ellipse shows the standard deviation of the points along each axis. The dimensions of this ellipse are 82 nm axially (z) and 32 nm in the transverse dimension (x,y). These points are then converted to cylindrical coordinates and plotted in Fig. 6 (c), revealing a lack of molecules for low radial distances. The ellipse from (b) is also converted to cylindrical coordinates and shown in (c). Next, we calculate a histogram of the radial distance from the fit line, which is shown in (d). From this histogram, we observe that the object we are reconstructing is not simply a line, but in fact a cylinder. The method is not only able to generate large images with enhanced resolution as in Fig. 5, but is in fact producing quantitative measurements of 3D properties of the microtubules. Since the precision differs significantly in the axial dimension, we classify the location of the points as either “axial” or “transverse”, as indicated by the color and shape of the points in (b) and (c). The anisotropy in localization precision is responsible for more points being classified as “axial” rather than “transverse,” i.e. even with a uniform distribution of labels, the distribution of localizations will be skewed along the axial direction. The simulations presented in the Supplementary Information exhibit the same behavior (see Fig. S1). We calculate the separate histograms of the radial distance for the two classifications of points and plot them in (e) and (f). From these histograms, we measure the median radial distance to be 49 nm and 75 nm in the transverse and axial dimensions, respectively.

Measurement of the 3D cylindrical structure of an antibody labeled microtubule.

A small region of the data containing a straight segment of a microtubule is shown in (a). In the context of the large image in Fig. 5, this region is indicated with a small white box on the right side of the image. These points are fit to a line in 3D space and the distance from each point to the fit line is shown in (b); this can also be thought of as a view of the microtubule from the perspective of the microtubule axis. The same plot is converted to cylindrical coordinates and displayed in (c). Plots (d)–(f) all show histograms of the radial distance of the points to the fit line; (d) shows all points and (e) and (f) show the points classified as transverse and axial points, respectively. From these histograms, it is apparent that we are observing emitters that are attached to a cylindrical object. Simulations presented in the Supplementary Information verify that the distributions observed here are consistent with a mirotubule having a 35 nm radius.

Prior reports have shown that antibody labeled microtubules have a radius of about 30 nm23. We performed an analysis taking into consideration the anisotropic precision of 3D localization leading to an estimate of the radius at 35 nm. Our analysis based on the results of Fig. 6 was obtained with a median of 614 detected photons per molecule. The experimental photon count is lower than the values used in simulations, resulting in lower localization precision24. On the other hand, lower precision enables the use of a coarser dictionary. The predicted experimental localization precisions for that intensity level are 30 nm and 66 nm in the transverse and axial dimensions, respectively22. Such anisotropy causes the circular cross-section of the microtubule to appear elliptical, as mentioned previously. Subsequently, we estimate the radius of the antibody labeled microtubule based on the known localization precision of 131 emitters fitted to the observed elliptical cylinder, leading to a precision surpassing that of an individual localization. The estimation result for the radius, including the antibody labeling structure, is 35 nm±12 nm. The error is given as one standard deviation. A slightly larger radius could be attributed to a minor bending of the microtubule or simply to the low photon count of our measurements. It should be noted that a cylindrical shape of microtubules has been previously observed25, albeit in 2D and with emitters that yield more than 100 times more photons than in our experiment.

Discussion

The origin of the super-resolution capability is interesting to ponder, given that the raw images are limited by diffraction and deconvolution techniques provide only limited success26. First, an engineered 3D PSF is essential to retrieve 3D information, as is a 3D dictionary. Second, the fundamental assumption of sparsity, i.e. only up to a handful of emitters are located within the PSF area, provides the required prior knowledge to achieve effective resolution and localization. Hence, super-resolution and super-localization are ultimately enabled by the combination of 3D optical techniques and prior knowledge. Furthermore, these two concepts can be linked in that the increased structure of the DH-PSF contributes to the solution of the localization problem. While the task of correctly pairing lobes of overlapping DH-PSFs might be thought of as an inherent disadvantage of the PSF, the lobes have a particular shape and separation that can help discern the underlying emitter locations.

An important difference between the methods in this paper and other sparse reconstruction schemes27 is that our goal is not to generate a reconstruction of each image. Although a reconstruction image is obtained, the desired information is actually in the indices of the large coefficients in the sparse reconstruction. Each dictionary element has a physical meaning: the presence of a large coefficient in the solution means there is an emitter at the corresponding location.

In conclusion, the method presented here has the capability to resolve dense clusters of molecules (or other emitters) from a single image in three dimensions while maintaining the high 3D localization precision. Therefore, higher labeling density and significant decreases in data collection time for 3D super-resolution microscopy experiments are now possible. Because the technique enables superresolution imaging with far fewer image frames, hence reducing the data required to reconstruct a nanoscale resolution image, the method can be classified as a compressive imaging technique.

Methods

In this section, we provide algorithmic details on our methods. Specifically, the following section details the design choices necessary for generating a dictionary and how to use such a dictionary to estimate the locations of molecules using Matching Pursuit (MP) or Convex Optimization (CO). A description of the experimental methods can be found in the Supplementary Information. Furthermore, the sample preparation is described in Ref. 22.

Dictionary Generation

For the dictionaries used in the methods discussed in this paper, there are a few important guidelines to follow. The topics relevant to dictionary generation that are discussed in this section are: transverse step size, axial step size, amplitude scaling of dictionary elements and the use of Look-Up Tables (LUTs) in localization.

All methods discussed in this paper utilize a dictionary that consists of the 2D cross-sections of the 3D PSF corresponding to lateral and axial shifted locations of the point source. If the system is shift-invariant, for a given depth, all 2D PSFs are equal except for a transverse shift. The dictionaries are generated by first selecting a 3D window size and making a list of discrete 3D locations to fill this volume. A model is then used to generate the corresponding image for each point source location in the dictionary. The model may be either an ideal PSF, or it may be the result of calibration data. The step size of the locations in the dictionary determines the localization precision, so the natural tendency is to make the step size very fine. A wise choice would be to relate the step size to the limit of localization precision achievable in a given system, as calculated by the Cramer-Rao Lower Bound (CRLB)28. The effective pixel size (physical pixel size divided by magnification) in single-molecule detection systems is typically designed to sample the PSF at approximately Nyquist sampling, which results in effective pixel sizes on the order of 160 nm in our experiments. The CRLB, on the other hand, can be significantly lower (typically 10 to 20 nm). As a result, the dictionary requires sub-pixel shifts. Additionally, since the extent of the PSF is significantly larger than the step size, there is a high degree of similarity between adjacent dictionary elements. Hence, by definition, the dictionary is coherent29. Thus, finding the solution for the representation of a scene using such a dictionary is a more difficult problem than if we were to use an orthonormal basis.

Furthermore, the requirement for 3D information necessitates many dictionary elements at the same transverse location. The DH-PSF enables an extended depth of field (DOF) as compared to a standard aperture by approximately a factor of two. In our experiments using a 1.45 NA objective, the DOF with a DH-PSF is approximately 2 µm. However, since the CRLB is larger in the axial dimension than in the transverse dimensions, the axial step size can be also slightly larger than the transverse step size.

Because the dictionary contains discrete locations, the results will have a quantization error. Even if the localization algorithm returns the correct dictionary element for every emitter in a scene, there will still be a distribution of errors spanning a range between −d/2 to +d/2, where d is the step size. The standard deviation of a uniform distribution with a range of d is  . We choose to use standard deviation to characterize the error because it can be directly compared to the square root of the CRLB. For consistency, we also use standard deviation to quantify the magnitude of the error in simulations.

. We choose to use standard deviation to characterize the error because it can be directly compared to the square root of the CRLB. For consistency, we also use standard deviation to quantify the magnitude of the error in simulations.

The important output of our sparsity-based algorithms is not the reconstructed image, but the indices of the significant coefficients that make up the reconstruction. A high coefficient for a particular dictionary element means there is a bright emitter at that location. Each dictionary carries with it a LUT to convert the index of a dictionary element to a physical location in (x, y, z) coordinates. The LUT is a Dx3 matrix, where D is the number of dictionary elements. There are three columns because the solution space is 3D. Each row contains the (x, y, z) values describing the location of an emitter that would generate the PSF in the corresponding index of the dictionary. The LUT is easily generated alongside the dictionary and provides a simple way to obtain a physical interpretation of the coefficients in the solution.

Each element of the dictionary is normalized such that its L2 norm is unity. As a result, the product of the coefficient and the dictionary element matches the intensity of that component in the image. The corresponding number of photons is calculated by multiplying the coefficient with the L1 norm of that particular basis element. The photon count calculation is correct only after the data has been converted from camera counts to photons. A matrix containing the L1 norms for each dictionary element is calculated beforehand and stored with the dictionary for fast conversion from coefficient values to photon counts. When implementing MP, it is necessary to calculate photon counts frequently, since one of the stopping criteria for the iterative method requires knowledge of the number of photons (stopping criteria are discussed in the following section).

Estimation

If the dictionary were an orthonormal basis set, the coefficients for representing the image could be found very easily: they would be the inner product of the image and each individual dictionary element. However, the use of small sub-pixel shifts means adjacent dictionary elements have a high degree of similarity; they are not orthogonal. Therefore, the coefficients must be found in a different manner. The two methods we propose to solve the estimation problem are Matching Pursuit (MP) and Convex Optimization (CO). These two approaches are described in this section.

Conceptually, MP is similar to finding coefficients for an orthonormal dictionary. In one iteration of MP, the image is projected onto the dictionary, just as if the dictionary were orthonormal. However, instead of keeping all the resulting coefficients, only the largest coefficient is stored as part of the solution. Next, that element is subtracted from the image20. Iterations continue until a stopping criterion is met, as described below.

Our implementation of the Matching Pursuit (MP) algorithm uses three different stopping criteria. The first stopping criterion limits the number of iterations (i.e. the maximum number of emitters the algorithm will return for a given scene). Simulations indicate the reliability of the algorithms decreases as the emitter density increases. Therefore we do not record results that are likely to be erroneous. Not only is a limit placed on the maximum number of iterations, but the order in which results are subtracted from the scene is also recorded. With this information, we can observe the performance of the iterative algorithm as the density increases in an experimental setting.

Another stopping criterion is the minimum estimated number of photons from an emitter. Even when all the emitters in a scene have been accounted for and subtracted, the remainder will still have positive values due to noise (particularly background noise). This could lead to spurious emitters in the reconstruction. To avoid this, MP ends iterations if the photon count of the strongest remaining component is below a threshold. The threshold can be determined beforehand based on the emitters used in the experiment, or decided after the experiment based on the data set. In the latter case, a preliminary threshold must be set to a very low value. Once MP is complete, the threshold is raised and the weakest emitters are excluded from the results.

The final criterion involves placing a limit on the value of pixels in the remainder image. As above, when all actual emitters in a scene are accounted for and subtracted, there will still be a remainder due to noise. Once the maximum pixel value in the remainder image drops below the expected value of background in the data set, the subsequent localizations are most likely the result of noise. Therefore, the iterations are stopped when the maximum of the remainder image drops below a threshold. Typical background levels can be predicted accurately from examining statistics of the whole data set. Furthermore, the threshold is usually set slightly below the background level (by perhaps 75%) to avoid false negatives. This criterion was found to terminate iterations more frequently than the photon counts criterion, while significantly speeding up the computation time. The reason for the speed increase is because this criterion is evaluated before the remainder image is projected onto the dictionary, whereas the minimum photon number criterion is evaluated after a projection. The speed increase is simply due to a reduced number of computed projections.

Implementations of MP (or other iterative algorithms) in other fields employ a stopping criterion that compares the reconstructed image to the raw data20. Iterations stop when the error between the two has reached an acceptable level. Such a stopping criterion is less applicable here because the goal is not to produce an accurate reconstruction of each frame. Rather, the goal is to estimate the locations of emitters. A limit on the error between the reconstruction and the original data would be meaningless in the case of a scene that contains no emitters. In fact, such a stopping criterion would often be at odds with the previous two criteria and therefore it cannot be seamlessly combined with the other stopping criteria.

Estimation using CO, on the other hand, attempts to arrive at a solution for the significant coefficients in parallel. Although the estimation method is quite different, the use of the algorithm is similar—the inputs are a window of data and a dictionary and the output is a list of coefficients that describe the data. The reconstruction problem is formulated as a convex problem in which the variable to be optimized is the sparsity of the coefficient vector (quantified as the L1 norm). This can be phrased mathematically as:

where x is the set of coefficients, A is the dictionary and ε is an error bound related to the total intensity in the image9. In this formalism, the image b has been folded into a column vector. In our implementation, we use CVX, a MATLAB package for solving convex problems21.

References

Betzig, E. et al. Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. Science 313, 1642–5 (2006).

Rust, M. J., Bates, M. & Zhuang, X. Sub-diffraction-limit imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM). Nat. Methods 3, 793–795 (2006).

Hess, S. T., Girirajan, T. P. K. & Mason, M. D. Ultra-high resolution imaging by fluorescence photoactivation localization microscopy. Biophys. J. 91, 4258–72 (2006).

Weiss, S. Measuring conformational dynamics of biomolecules by single molecule fluorescence spectroscopy. Nat. Struct. Bio. 7, 724–9 (2000).

Yildiz, A., Tomishige, M., Vale, R. D. & Selvin, P. R. Kinesin walks hand-over-hand. Science 303, 676–8 (2004).

DeLuca, J. G. et al. Kinetochore microtubule dynamics and attachment stability are regulated by Hec1. Cell 127, 969–82 (2006).

Heisenberg, W. The Physical Principles of the Quantum Theory (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1930).

Fölling, J. et al. Fluorescence nanoscopy by ground-state depletion and single-molecule return. Nat. Methods 5, 943–945 (2008).

Zhu, L., Zhang, W., Elnatan, D. & Huang, B. Faster STORM using compressed sensing. Nat. Methods 9, 721–3 (2012).

Cox, S. et al. Bayesian localization microscopy reveals nanoscale podosome dynamics. Nat. Methods 9, 195–200 (2012).

Huang, F., Schwartz, S. L., Byars, J. M. & Lidke, K. A. Simultaneous multiple-emitter fitting for single molecule super-resolution imaging. Biomed. Opt. Express 2, 1377–93 (2011).

Barsic, A. & Piestun, R. Super-resolution of dense nanoscale emitters beyond the diffraction limit using spatial and temporal information. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 231103 (2013).

Babcock, H., Sigal, Y. M. & Zhuang, X. A high-density 3D localization algorithm for stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy. Optical Nanoscopy 1, 6 (2012).

Dertinger, T., Colyer, R., Iyer, G., Weiss, S. & Enderlein, J. Fast, background-free, 3D super-resolution optical fluctuation imaging (SOFI). PNAS 106, 22287–92 (2009).

Geissbuehler, S., Dellagiacoma, C. & Lasser, T. Comparison between SOFI and STORM. Biomed. Opt. Express 2, 408–20 (2011).

Kao, H. P. & Verkman, A. S. Tracking of single fluorescent particles in three dimensions: use of cylindrical optics to encode particle position. Biophys. J. 67, 1291–300 (1994).

Ram, S., Chao, J., Prabhat, P., Ward, E. S. & Ober, R. J. A novel approach to determining the three-dimensional location of microscopic objects with applications to 3D particle tracking. Proc. SPIE 6443, 64430D–64430D–7 (2007).

Pavani, S. R. P. & Piestun, R. High-efficiency rotating point spread functions. Opt. Express 16, 3484–9 (2008).

Quirin, S., Pavani, S. R. P. & Piestun, R. Optimal 3D single-molecule localization for superresolution microscopy with aberrations and engineered point spread functions. PNAS 109, 675–9 (2012).

Bergeaud, F. & Mallat, S. Matching pursuit of images. In: Proc. of Intl. Conf. on Image Processing, vol. 1, 53–56 (1995).

Boyd, S. & Vandenberghe, L. Convex Optimization (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Grover, G., DeLuca, K., Quirin, S., DeLuca, J. & Piestun, R. Super-resolution photon-efficient imaging by nanometric double-helix point spread function localization of emitters (SPINDLE). Opt. Express 20, 26681–95 (2012).

Bates, M., Huang, B., Dempsey, G. T. & Zhuang, X. Multicolor super-resolution imaging with photo-switchable fluorescent probes. Science 317, 1749–53 (2007).

Thompson, R. E., Larson, D. R. & Webb, W. W. Precise nanometer localization analysis for individual fluorescent probes. Biophys. J. 82, 2775–83 (2002).

Vaughan, J., Jia, S. & Zhuang, X. Ultrabright photoactivatable fluorophores created by reductive caging. Nat. Methods 9, 1181–1184 (2012).

McNally, J. G., Karpova, T., Cooper, J. & Conchello, J. A. Three-dimensional imaging by deconvolution microscopy. Methods 19, 373–85 (1999).

Candes, E., Romberg, J. & Tao, T. Stable signal recovery from incomplete and inaccurate measurements. Communications on pure and applied mathematics 59, 1207–1223 (2006).

Grover, G., Pavani, S. R. P. & Piestun, R. Performance limits on three-dimensional particle localization in photon-limited microscopy. Optics letters 35, 3306–8 (2010).

Candes, E. J., Eldar, Y. C., Needell, D. & Randall, P. Compressed Sensing with Coherent and Redundant Dictionaries. arXiv.org arXiv:1005.2613v3 [math.NA], 1–21 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation awards DBI-1063407 and DGE-0801680, an Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship program in Computational Optical Sensing and Imaging. We thankfully acknowledge Jennifer and Keith DeLuca for providing the samples, Eyal Niv for helpful discussions and Sean Quirin for fabricating the phase mask used in the experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B. and R.P. conceived the methods. G.G. performed the experiments. A.B. carried out the simulations and data processing. A.B. and R.P. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

R.P. has a financial interest in Double Helix LLC, which, however, did not support this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Barsic, A., Grover, G. & Piestun, R. Three-dimensional super-resolution and localization of dense clusters of single molecules. Sci Rep 4, 5388 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05388

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05388

This article is cited by

-

Birefringent Fourier filtering for single molecule coordinate and height super-resolution imaging with dithering and orientation

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Recent advances in point spread function engineering and related computational microscopy approaches: from one viewpoint

Biophysical Reviews (2020)

-

A Perspective on Data Processing in Super-resolution Fluorescence Microscopy Imaging

Journal of Analysis and Testing (2018)

-

Extracting quantitative information from single-molecule super-resolution imaging data with LAMA – LocAlization Microscopy Analyzer

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Generalized recovery algorithm for 3D super-resolution microscopy using rotating point spread functions

Scientific Reports (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.