Abstract

Negative-index metamaterials (NIMs) exhibiting both negative refraction as well as phase reversal, particularly in the visible range, have drawn considerable attention in the past decade due to their potential applications in cloaking, sensing and sub-diffraction-limit imaging. NIM are often realized by arraying sub-wavelength nanostructures (meta-atoms) exhibiting spectrally overlapped magnetic and electric resonances. Most designs so far use scaling down of the resonant elements and employ materials with the right optical constants to obtain NIM in the visible range. However, large losses due to absorption in most metals and semiconductors as well as reduced coupling with light due to scaling pose a challenge to achieving low-loss NIM. Here, we employ plasmon hybridization in semiconductor-metal-semiconductor core-multishell (CMS) nanowires as a unique approach to design low loss, isotropic and polarization dependant NIM in the visible range. Based on numerical simulations, we demonstrate an effective refractive index of −1 and a figure of merit (FOM) of 17 at 650 nm for a representative Si-Ag-Si CMS nanowire NIM and a refractive index of −1, FOM of 25 at 590 nm for a GaP-Ag-GaP CMS nanowire NIM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the past decade many breakthroughs have been made towards realizing isotropic, bulk negative-index metamaterial (NIM) in various spectral regimes1,2. Specifically, in the visible range, negative refraction has been demonstrated using metallic nanowires embedded in a dielectric matrix3,4, fishnet structures5,6,7, metal-dielectric stacks/sandwiches8,9,10, planar waveguides11 and metal-insulator-metal coaxial waveguides12,13. Despite the tremendous progress in the design and fabrication of NIM, developing high performance NIM without active loss compensation in the optical domain remains a challenge. This is due to large losses arising from both the NIM designs as well as the materials. The best experimental value for the figure of merit  reported so far are 3.34 in the visible and 3.5 in near-infrared range obtained from fishnet NIM7,14.

reported so far are 3.34 in the visible and 3.5 in near-infrared range obtained from fishnet NIM7,14.

More recently, theoretical designs have been reported for low loss plasmonic NIM utilizing the geometry dependant Mie excitations in Ag-GaP hybrid rods15, Ag-Si core-shell (CS) nanospheres16 and nanowires17. Specifically, in the CS structures the core diameter and the shell thickness are chosen so that the magnetic dipole resonance arising from the dielectric shell and the electric dipole resonance (localized surface plasmon resonance - LSPR) in the metal core spectrally overlap. Around this double resonance, both the electric and magnetic dipole moments in the nanosphere/wire are strongly negative. These sub-wavelength CS structures demonstrating such double resonance feature satisfy the requirements of a NIM meta-atom, therefore CS structures can be engineered into a NIM with simultaneously negative permittivity and permeability. Since the natural magnetic resonance occurring in the dielectric shell is coupled to the LSPR within the same CS nanostructure, the losses due to the NIM design in CS structures are significantly suppressed, resulting in higher FOM. While NIM based on CS nanospheres are polarization independent16,18, nanowire (NW) structures are polarization dependent due to their high aspect ratio. This anisotropy enables stronger light coupling and leads to stronger resonance, hence the NIM based on nanowires exhibit substantially higher FOM17. The Ag-Si CS nanowire based NIM has been predicted to demonstrate a FOM of approximately 85 for a refractive index of −1 in the wavelength range between 1.2 and 1.5 μm, which is the highest FOM predicted in that range. Since surface plasmon resonance (electric resonance) wavelength for the CS structures depends on the diameter of the core, scaling down the core is a possible strategy to tune the double resonance of the Ag-Si CS nanowires into the visible domain. However, scaling down the core reduces the coupling with light, resulting in a strong reduction in the resonance strength and consequently the FOM. Alternatively, it has been suggested to add a thin intermediate dielectric layer with a low permittivity between the core and the shell, together with scaling down the diameters, in order to move the NIM behavior towards visible wavelengths17,18.

In this work, we present a new group of NIM meta-atoms for the visible range based on semiconductor-metal-semiconductor core-multishell (CMS) nanowires. In the CMS structures, under transverse electric (TE – magnetic field along the axis of the nanowire) polarization, the plasmon hybridization in the metal shell is used to tune the double resonance into the visible domain. We choose Si, the most technically important semiconductor and Ag, the metal with the lowest losses in the visible range, to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach. Compared to the previous NIM studies based on core-shell meta-atoms, the uniqueness of the proposed approach is two-fold. First, distinguished from scaling down the meta-atom diameter or introducing low-permittivity intermediate layer as suggested in previous studies16,17,18, we utilize plasmon hybridization to tune the electric resonance. Consequently, the CMS structures avoid the reduction in the resonance strength accompanied by scaling down the size and also circumvent the need for a low-permittivity intermediate layer. Second, we specifically study CMS nanowire meta-atoms with double resonance in the visible range. In comparison, the CS nanowire based NIM studies done by Paniagua-Domínguez and co-workers17 focused on double resonance in the NIR region (1.2–1.5 μm).

Results

Plasmon Hybridization in CMS nanowires

Plasmon hybridization was first extensively studied in Au nanoshells19,20,21. For a single metal shell, the cavity plasmon and the surface plasmon hybridize to form symmetric and anti-symmetric plasmons of which frequencies are significantly different. Similar hybridization has been studied in metal nanotubes22,23 and coupled metal nanowires24. Plasmon hybridization in the nanowires structures can be succinctly described in a manner similar to molecular orbital hybridization, as shown in Figure 1a Inset18,19,20. Here, the Si (red) nanowire in Ag (grey) exhibits a cavity plasmon (ωc) and the Ag nanowire in Si exhibits a surface plasmon resonance (ωNW). The Si-Ag CS nanowire embedded in Si, a superposition of two systems discussed above, would result in a hybridized case. Here, the cavity and surface plasmons hybridize to give a symmetric (ω−) plasmon with a lower energy and an anti-symmetric (ω+) plasmon with a higher energy, compared to the constituent plasmons. This large difference in the resulted plasmon resonance wavelengths ensures tunability over a large range that would otherwise require significant reduction or increase in the size of the nanostructure.

Plasmon hybridization.

(a) Extinction efficiency as a function of wavelength for a Si (80 nm dia.) nanowire (NW) embedded in Ag medium (black curve), Ag (120 nm) nanowire in Si medium (red curve) and Si(80 nm dia.)-Ag (20 nm) CS nanowire in Si medium (green curve). Inset: schematic of plasmon hybridization. Ag and Si are represented in grey and red color respectively. (b–e) |E| contour plots corresponding to the (b) cavity plasmon in (580 nm), (c) surface plasmon (650 nm), (d) anti-symmetric (440 nm) and (e) symmetric (1200 nm) hybridized plasmons.

To obtain a more detailed picture of plasmon hybridization in nanowire structures, we calculate the optical response of three systems illustrated in Figure 1a Inset, i.e. the Si nanowires in Ag (black), the Ag nanowires in Si (red) and the Si-Ag CS nanowire embedded in Si (green), under TE polarized light incident normal to the nanowire axis using Mie formalism25 (see Methods and Supplementary Information). For Si and Ag, the absorbing medium considered here, the fields calculated using Mie formalism are accurate as they explicitly account for the optical constants of the medium and the extinction (scattering) efficiency depends on the volume of the medium considered. In order to calculate the extinction efficiencies for nanowires, the medium is often assumed as a cylindrical shell with a radius larger than the nanowire. To the first order, the extinction efficiency exponentially decays with increasing radius of the medium26,27,28,29. In our work, calculation of extinction efficiencies is based on the far-field approximation and therefore they do not represent the true extinction of the nanowire alone. However they provide an insight on the approximate wavelengths of plasmon resonance. The electric and magnetic near-field contours also shown in our work indeed will accurately capture the plasmon resonances.

Among all possible geometric combinations, we chose the diameter of the Si nanowires (i.e. nanowire core) to be 80 nm, the diameter of the Ag nanowires to be 120 nm and the thickness of the Ag shell in the CS structure to be 20 nm, because the CMS structures based on identical dimensions have been found to meet double resonance conditions as will be shown subsequently. Figure 1a plots the extinction efficiencies of the three structures calculated. The peaks at 580 nm (black curve) and 650 nm (red curve) correspond to the cavity and surface plasmon resonance. The extinction efficiency of the Si-Ag CS structure in Si medium shows two peaks at 440 nm and 1200 nm (green curve), which occur at substantially lower and higher wavelengths as compared to the cavity and surface plasmon resonance, respectively. This is consistent with the expectation that the hybridized anti-symmetrical plasmon occurs at a higher energy while the symmetrical plasmons occurs at a lower energy, as presented in the schematic.

To further confirm the plasmon hybridization, we also study the electric field distribution around the cavity/nanowires. The near-field contours at the wavelengths corresponding to the extinction efficiency peaks are plotted in Figure 1b–e. The electric field contours for the Si nanowire in Ag (Fig. 1b) and the Ag nanowire in Si (Fig. 1c) clearly show dipolar and quadrapolar behavior respectively, confirming the presence of LSPR in both structures. Further, for the Si/Ag CS structure in Si medium, the electric field contours show the anti-symmetrical and symmetrical features of the coupled plasmons. At 440 nm the dipoles inside and outside the Ag shell are opposite in direction (Fig. 1d), while at 1200 nm the dipoles are aligned in the same direction (Fig. 1e). The corresponding magnetic near-field contours are plotted in Supplementary Figure S1.

Tunable visible range double resonance in CMS nanowires

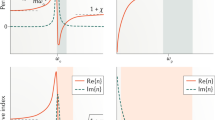

Based on the plasmon hybridization picture presented above, we designed a Si-Ag-Si CMS structure (Fig. 2a Inset), in which the thickness of the Si outer shell is optimized so that the magnetic resonance in the Si outer shell overlaps with the anti-symmetric plasmon wavelength in the Ag inner shell. We found that for a representative CMS nanowire with an 80 nm diameter Si core and a 20 nm thick Ag inner shell, a 30 nm thick Si outer shell results in a double resonance in the visible domain. For this specific CMS structure under TE illumination, we calculated and plotted the total scattering efficiency as well as the scattering contribution of the magnetic and electric dipolar Mie coefficients as functions of wavelength in Figure 2a. The grey shaded area highlights the region of the double resonance occurring between 620 to 730 nm, which later will be demonstrated as the working range of the NIM composed of these CMS structures. Additionally, the real and imaginary parts of the electric and magnetic polarizabilities normalized with the cross-sectional area of the CMS nanowire are plotted in Figure 2b and c (see Methods). In the shaded wavelength range, strongly negative electric and magnetic polarizabilities (i.e. dipole moments) are clearly observed. The magnetic field distribution in the Si outer shell and the circulation in the electric field provide further confirmation of the double resonance. The magnetic and electric near-field contours at 660 nm are plotted in Figure 2d. These results collectively show that CMS structures demonstrate strong double resonances and therefore are promising meta-atom systems for NIM in the visible domain. In addition, the feature dimensions of the CMS structure, including the Si core diameter, the Ag shell thickness and the Si outer shell thickness, offers great tunability of the double resonance wavelengths. For example, when increasing the Si outer shell thickness, the anti-symmetric plasmon frequency blue shifts while the symmetric plasmon does the opposite.

Double resonance in CMS nanowires.

(a) Total scattering efficiency and contributions of the first (magnetic) and second (electric) Mie coefficients of a Si (80 nm dia.)-Ag (20 nm)-Si (30 nm) CMS nanowire under TE illumination. Inset: schematic representation of the CMS nanowire structure. (b) and (c) are the corresponding normalized electric and magnetic polarizabilities respectively. The shaded grey region represents the spectral region of double resonance. (d) Magnetic and Electric near-field contours at 660 nm TE incidence.

To gain a deeper insight into the tunability of CMS structures, we varied the core diameters and shell thicknesses, while identifying the electric and magnetic resonance wavelengths and searching for their spectral overlap. Specifically, we first computed the product of the scattering contributions from the first two Mie coefficients as functions of wavelength, i.e. Qmagnetic(λ,rj)*Qelectric(λ,rj). Here rj is the core radius, shell and outer shell thickness for j = 1, 2 and 3 respectively. This product indeed characterizes the overlapping between the electric field resonance and the magnetic field resonance. We define the maximum of this product as the correlation function (Corr(rj); see Methods for details) and identify the corresponding wavelength (λcorr(rj)) at which the maximum of this product occurs. The correlation (Corr(rj)) and the corresponding wavelengths (λcorr(rj)) were obtained for multiple outer shell thicknesses and plotted in Figure 3a. The peaks in the correlation vs. shell thickness graph represent double resonance. Analysis were performed for three groups of structures in which the Si core diameters are chosen to be 160 nm, 80 nm and 40 nm respectively and Ag shell thicknesses are all fixed at 20 nm. In Figure 3a the correlation function shows peaks at 65, 30 and 25 nm outer shell thicknesses and corresponding double resonance wavelengths are 1080, 660 and 570 nm respectively. These results indicated that by varying only the outer shell thickness in a Si-Ag-Si CMS we can tune the double resonances in a broad range covering the visible spectrum. The correlation analysis for Ag-Si CS nanowires was also performed and shown in Figure 3b. For 200, 80 and 40 nm Ag core diameters, a Si shell thicknesses of 110, 55 and 55 nm resulted in a double resonance at 1540, 860 and 750 nm respectively. All double resonance features found for three CS structure are 750 nm or above (dash line in Figure 3a and b bottom panels) while the CMS nanowires clearly exhibit a substantial blue shift in the double resonance, with two of double resonances shifted to the visible range. We note that the CS structures considered in Figure 3b are identical to CS meta-atoms studied by Paniagua-Domínguez and co-workers17, which are made of a 160 nm diameter Ag core and a 90 nm thick Si shell showing a double resonance at 1300 nm. These CS meta-atoms indeed cannot be tuned into the visible range with scaling alone. An additional low-permittivity layer between the Ag and Si would be necessary for CS structures to achieve a strong double resonance at the same wavelength as the CMS nanowire counterparts17,18. Notably, among all CMS structures, the heights of correlation peaks obtained for 160 and 80 nm core diameters are comparable, indicating that the electric and magnetic dipole strength does not significantly change in this range of core diameters. While considering the core diameter below 80 nm, we observed a decrease in the correlation peak height and electric dipole moment (Shown in Supplementary Figure S2), indicating weaker resonance and poorer coupling with light for thinner cores. A similar trend is also observed in the CS nanowires with core diameters smaller than 80 nm. These results suggested a limitation for tuning the working range of NIM based on the CS and CMS structures considered by scaling down alone.

NIM Tunability.

Correlation and the corresponding wavelengths as functions of the outer shell thicknesses of (a) CMS and (b) CS NWs. In CMS NWs, the Si core diameters are 160 nm (Black), 80 nm (Red) and 40 nm (Green) respectively and Ag shell thicknesses are all fixed at 20 nm. In CS NWs, the Ag shell thickness are 200 nm (Black), 80 nm (Red) and 40 nm (Green), respectively.

Effective refractive index and FOM of CMS nanowire arrays

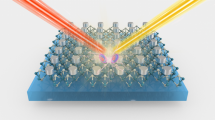

We have so far shown that the CMS nanowires can be considered as individual meta-atoms with strong resonance in the visible range. We now present full numerical simulations to demonstrate that a slab consisting of CMS nanowire array behaves as low loss and isotropic NIM. Based on the above analysis, we choose a core diameter of 80 nm in order to have sufficiently strong double resonance. As for the Ag intermediate shell, choosing the right thickness is critical since it should provide visible range plasmon resonance without resulting in loss of resonance strength. Thinner shells lead to weaker double resonance in the visible range while thicker layers exhibit stronger resonance albeit in the NIR range (Supplementary Figure S3). Therefore, keeping these constraints in mind, we choose a 20 nm Ag shell thickness for our representative CMS nanowire to ensure strong visible range double resonance. For these core and shell sizes, a 30 nm Si outer shell is needed to obtain double resonance at 660 nm as shown in Figure 2a.

Considering a slab made of Si (80 nm dia.)-Ag (20 nm)-Si (30 nm) CMS nanowires, we performed full numerical simulations using COMSOL Multiphysics (see Methods) and extracted the effective refractive index. The CMS nanowires were arranged in a hexagonal lattice in the NIM slab extending infinitely along the slab width. A schematic of the slab is shown in Figure 4a inset. The pitch, defined as the spacing between a nanowires axis to the axis of its neighbor nanowires, was chosen to be 200 nm. Assuming a plane-wave TE polarized incidence at 20° to the normal as depicted in Figure 4a inset, the complex transmission and reflection coefficients, S-parameters, can be obtained from simulation for various slab thicknesses (2–60 nanowire layers). The imaginary part of the refractive index was extracted from the S-parameters, while the real part was obtained by graphically measuring the refracted wave-vector when assuming an error of ±2° and applying Snell's law (see Methods). The results are plotted in Figure 4a. A slab with a thickness of 25 nanowire layers was used for measuring the refracted wave-vector as well as the transmission through the slab. The region of double resonance was found to be 620 to 730 nm and it defines the transmission window of the slab which corresponds to the NIM working range. Beyond this range, the slab exhibits large absorption, consistent with that observed in Ag-Si CS nanowire NIM slabs17. Further, the dynamically extended contour plot of the electric field (Supplementary Video 1) shows the light wave undergoes both negative refraction and phase reversal within the NIM slab. This confirms that the NIM slab consisting of CMS nanowires exhibits simultaneously negative permittivity and permeability. Figure 4b plots the FOM for the Si-Ag-Si CMS nanowire NIM slab. Specifically at 660.3 nm, the effective refractive index is estimated to be −1.1738(±0.0410) + 0.0686i, resulting in a FOM of approximately 17. The refractive index of −1 observed around 650–660 nm opens up possible applications towards visible light super-lenses. The maximum FOM is found to be about 26 at 700 nm, which is among the highest FOM predicted for passive NIM in the visible range.

Effective refractive index.

(a) The real part (green curve) and imaginary part (blue curve) of the effective refractive index of a slab based on Si (80 nm dia.)-Ag (20 nm)-Si (30 nm) nanowires for a 20° TE plane-wave illumination. The error bars in the real part of the refractive index (green curve) are estimated based on the ±2° error assumed while measuring the refracted angle. Inset: schematic of the slab based on CMS nanowires arranged in a hexagonal lattice. (b) The corresponding FOM. (c) Transmission through the NIM slab for two different pitch lengths as a function of the angle of incidence.

Understanding the effect of illumination angles on the effective index will help us confirm whether NIM slab is isotropic, which is a key requirement for super-lensing applications. To this end, the transmission through the slab as a function of the angle of incidence is a good indicator of isotropy of the NIM. As shown in Figure 4c, the transmission at 651.72 nm is fairly constant between incidence angles of 0° and 30°and again between 40° and 70°, which indicates that the NIM is isotropic for these ranges. There is a substantial drop in transmission between 30° and 40° which can be attributed to the increased absorption caused by Fabry-Perot like resonances in the nanowire array17.

Notably, increasing the fill factor of the meta-atoms in the NIM has been shown to substantially improve the FOM16,17,18. For instance, high FOM in Ag-Si CS nanowire NIM was obtained for hexagonal close packing arrangement with 10 nm separation between adjacent nanowire surfaces resulting in a fill factor of about 0.85617. To achieve a high FOM, in principle the nanowires should be arranged as close to each other as possible without touching each other to ensure that the double resonance remains unperturbed. In our simulations, we consider arrays with fill factors which are easily accessible through either top-down etching, bottom-up vapor-liquid-solid (VLS) growth or a combination of both. Considering a pitch of 200 nm for the Si (80 nm dia.)-Ag (20 nm)-Si(30 nm) CMS wires evaluated in the simulations, the distance between nanowire surfaces is 20 nm and the fill factor is about 0.7346. Hence, with the development of highly precise fabrication techniques to achieve higher fill factors, we expect the FOM to be further improved.

This approach of using CMS geometry can be extended to other materials to tune the working range of the NIM and to improve FOM. For example, GaP has nearly negligible losses in the visible range and a dielectric constant slightly smaller than Si. Hence we expect GaP-Ag-GaP nanowire NIM to result in an improved performance in the visible domain over Si-Ag-Si nanowire NIM. Due to the lower permittivity, the double resonance in a GaP (80 nm dia.)- Ag (20 nm)- GaP (30 nm) CMS nanowire is blue shifted when compared to Si-Ag-Si nanowire of same dimensions (Supplementary Figure S5). The working range of a NIM consisting of these GaP-Ag-GaP CMS nanowires is between 540 and 640 nm. The effective refractive index and FOM over this range show trends similar to Si-Ag-Si nanowire NIM and the results are plotted in Supplementary Figure S6. As expected from the lower losses in GaP, the FOM for GaP based NIM is substantially higher than Si based NIM. Specifically at 590.1 nm, the effective refractive index is −1.0307(±0.036) + 0.0401i and the corresponding FOM is about 25. Further, the maximum FOM of 36 is achieved, which is substantially higher than the Si counterpart.

Discussion

In this work, we have shown that semiconductor-metal-semiconductor CMS nanowires can be designed to exhibit double resonance in the visible range under TE illumination. Such structures offer good visible range tunability where the plasmon hybridization in the metal shell is utilized to shift the double resonance. This circumvents the need for large scaling down of the nanowire diameters which is often required in the metal-semiconductor CS for achieving the double resonance towards the visible range. Further, the CMS nanowires exhibit strongly negative electric and magnetic dipole moments and hence can be used as meta-atoms for engineering low-loss, isotropic, polarization dependant NIM slabs. Using full numerical simulations we have demonstrated that NIM slabs consisting of Si-Ag-Si nanowire arrays have a negative refractive index between 620 and 730 nm with a FOM of ~17 at 660.3 nm. For a NIM slab made of GaP-Ag-GaP nanowire arrays of comparable size, the working range is between 540 and 640 nm with a FOM of ~25. This value is among the highest estimated for passive NIM in the visible range. Simulations established in our work provide a general guideline for design and optimize CMS structures as well as predicting the experimentally achievable FOM. Further, since the CMS architecture offers high tunability of the plasmon resonance while ensuring good coupling with light, we expect such structures to also open up potentials in sensing and efficient light harvesting applications.

Methods

Analytical solutions

Mie formalism25 was used to solve Maxwell's equations analytically to obtain scattering, extinction and absorption efficiencies as well as electric and magnetic near-field contours (See Supplementary Information Section 1 for a detailed derivation). Optical constants of all materials were interpolated from Sopra data for coating films30 to ensure that our calculations provide a good prediction of the experimentally realizable results.

The magnetic (and electric) polarizability have been obtained from the magnetic moment of the nanowire. The magnetic and electric polarizability have been obtained from the magnetic moment of the nanowire. Under TE illumination of the form e−iωt, propagating along  , the polarization P of the nanowire in given as:

, the polarization P of the nanowire in given as:

The polarization current is:

The magnetic moment is given as:

The nanowires are assumed to be infinitely long (i.e. the length is much greater than the diameter) and hence a magnetic moment per unit length is defined as

Now the magnetic polarizability can be obtained from the magnetic moment and the magnitude of the incident field H0. We further normalize it with the area of cross section as follows,

The total electric dipole moment is obtained by integrating the polarization over the nanowire cross-section. Since the incident electric field is along  , the dipole moment per unit length is given as

, the dipole moment per unit length is given as

The electric polarizability per unit length normalized with the area of cross-section is obtained from the dipole moment and the incident field ε0E0 as follows,

The polarizabilities have been normalized in this manner in order to easily elucidate the phase change around double resonance leading to strongly negative polarizabilities. The exact magnitude of the polarizabilities can be easily retrieved from the above expressions.

Correlation

We define an arbitrary correlation function as follows:

Here rj is the core radius, shell and outer shell thickness for j = 1, 2 and 3 respectively. The corresponding correlation wavelength (λcorr(rj)) is the wavelength at which the maximum of Qmagnetic(λ,rj)*Qelectric(λ,rj) occurs. Now the peak in the correlation versus shell thickness graph indicates double resonance and the corresponding wavelength is the wavelength of double resonance. We have rigorously tested and confirmed that the correlation peaks indeed correspond to double resonance in CMS nanowires by comparing with the electric and magnetic dipolar scattering efficiency (as shown in Figure 2a).

NIM slab refraction and Parameter Retrieval

COMSOL Multiphysics 4.3a was used to perform full numerical 2D simulations of the NIM slab consisting of CMS nanowires arranged in a hexagonal lattice, where the wires are assumed to be infinitely long. The slab of nanowires extends infinitely along the width and Floquent periodic boundary conditions have been used to achieve this. Port boundary conditions have been used to obtain the complex transmission and reflection coefficients (S-parameters) of the slab. The effective refractive index of CMS nanowire NIM slab has been extracted from these complex transmission and reflection coefficients using standard retrieval procedures for many slab thicknesses (2–60 layers thick) to ensure convergence31. The imaginary part of the effective refractive index calculated in this manner converges quickly with increasing number of nanowire layers, i.e. slab thickness, hence giving reliable results. The real part of the effective index on the other hand oscillates even for a slab that is 60 layers thick. Beyond this point, the transmission through the slab becomes nearly zero making it impossible to extract the correct branch of the real part unambiguously (Supplementary Figure S4). Therefore, we present the real part of the effective index obtained graphically by measuring the angle of the refracted wave-vector and applying Snell's law. Similar to Paniagua-Domínguez and co-workers17, we assume a consistent error of ±2° in the measurements. In all COMSOL simulations, the optical constants of all materials were interpolated from Sopra data30.

References

Shalaev, V. M. Optical negative-index metamaterials. Nature Photon. 1, 41–48 (2007).

Soukoulis, C. M. & Wegener, M. Past achievements and future challenges in the development of three-dimensional photonic metamaterials. Nature Photon. 5, 523–530 (2011).

Liu, Y., Bartal, G. & Zhang, X. All-angle negative refraction and imaging in a bulk medium made of metallic nanowires in the visible region. Opt. Express 16, 15439–15448 (2008).

Yao, J. et al. Optical negative refraction in bulk metamaterials of nanowires. Science 321, 930 (2008).

Dolling, G., Wegener, M., Soukoulis, C. M. & Linden, S. Negative-index metamaterial at 780 nm wavelength. Opt. Lett. 32, 53–55 (2007).

Xiao, S., Chettiar, U. K., Kildishev, A. V., Drachev, V. P. & Shalaev, V. M. Yellow-light negative-index metamaterials. Opt. Lett. 34, 3478–3480 (2009).

García-Meca, C. et al. Low-Loss Multilayered Metamaterial Exhibiting a Negative Index of Refraction at Visible Wavelengths. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 067402 (2011).

Scalora, M. et al. Negative refraction and sub-wavelength focusing in the visible range using transparent metallo-dielectric stacks. Opt. Express 15, 508 (2007).

Jen, Y.-J. et al. Silver/silicon dioxide/silver sandwich films in the blue-to-red spectral regime with negative-real refractive index. App. Phys. Lett. 99, 181117 (2011).

Xu, T., Agrawal, A., Abashin, M., Chau, K. J. & Lezec, H. J. All-angle negative refraction and active flat lensing of ultraviolet light. Nature 497, 470–474 (2013).

Lezec, H. J., Dionne, J. A. & Atwater, H. A. Negative refraction at visible frequencies. Science 316, 430–432 (2007).

Burgos, S. P., de Waele, R., Polman, A. & Atwater, H. A. A single-layer wide-angle negative-index metamaterial at visible frequencies. Nature Mat. 9, 407–412 (2010).

de Waele, R., Burgos, S. P., Atwater, H. A. & Polman, A. Negative refractive index in coaxial plasmon waveguides. Opt. Express 18, 12770–12778 (2010).

Valentine, J. et al. Three-dimensional optical metamaterial with a negative refractive index. Nature 455, 376–379 (2008).

Kang, L. & Lippens, D. Mie resonance based left-handed metamaterial in the visible frequency range. Phys. Rev. B 83, 195125 (2011).

Paniagua-Domínguez, R., López-Tejeira, F., Marqués, R. & Sánchez-Gil, J. A. Metallo-dielectric core–shell nanospheres as building blocks for optical three-dimensional isotropic negative-index metamaterials. New J. Phys. 13, 123017 (2011).

Paniagua-Domínguez, R., Abujetas, D. R. & Sánchez-Gil, J. A. Ultra low-loss, isotropic optical negative-index metamaterial based on hybrid metal-semiconductor nanowires. Sci. Rep. 3, 1507 (2013).

Wu, D., Jiang, S., Cheng, Y. & Liu, X. Three-layered metallodielectric nanoshells: plausible meta-atoms for metamaterials with isotropic negative refractive index at visible wavelengths. Opt. Express 21, 1076–1086 (2013).

Westcott, S., Jackson, J., Radloff, C. & Halas, N. Relative contributions to the plasmon line shape of metal nanoshells. Phys. Rev. B 66, 155431 (2002).

Prodan, E., Radloff, C., Halas, N. J. & Nordlander, P. A hybridization model for the plasmon response of complex nanostructures. Science 302, 419–422 (2003).

Prodan, E. & Nordlander, P. Plasmon hybridization in spherical nanoparticles. J. Chem. Phys. 120, 5444–5454 (2004).

Moradi, A. Plasmon hybridization in tubular metallic nanostructures. Physica B 405, 2466–2469 (2010).

Turner, M. D., Hossain, M. M. & Gu, M. The effects of retardation on plasmon hybridization within metallic nanostructures. New J. Phys. 12, 083062 (2010).

Aubry, A., Lei, D. Y., Maier, S. A. & Pendry, J. B. Plasmonic hybridization between nanowires and a metallic surface: a transformation optics approach. ACS Nano 5, 3293–3308 (2011).

Kerker, M. & Matijevic, E. Scattering of Electromagnetic Waves from Concentric Infinite Cylinders. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 51, 506–508 (1961).

Bohren, C. F. & Gilra, D. P. Extinction by a spherical particle in an absorbing medium. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 72, 215–221 (1979).

Lee, S.-C. Light scattering by a coated infinite cylinder in an absorbing medium. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 28, 1067–1075 (2011).

Quinten, M. & Rostalski, J. Lorenz-Mie Theory for Spheres Immersed in an absorbing host medium. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 13, 89–96 (1996).

Sun, W., Loeb, N. G. & Lin, B. Light scattering by an infinite circular cylinder immersed in an absorbing medium. Appl. Opt. 44, 2338–2342 (2005).

Ni, X., Liu, Z. & Kildishev, A. V. PhotonicsDB: Optical Constants. https://nanohub.org/resources/PhotonicsDB (10.4231/D3FT8DJ4J). (2010).

Chen, X., Grzegorczyk, T., Wu, B.-I., Pacheco, J. & Kong, J. Robust method to retrieve the constitutive effective parameters of metamaterials. Phys. Rev. E 70, 016608 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. V. Shalaev and Dr. A. Kildishev for their valuable discussion on CS nanowire scattering calculations. We also thank Dr. G. Cheng for his guidance with COMSOL simulations. S.R. thanks the support from NSF ECCS 1118934.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Y. and S.R. conceived the idea and C.Y. provided guidance throughout the project. S.R. did the Mie scattering analysis for CMS nanowires and COMSOL simulations of the NIM slab. Both, C.Y. and S.R. contributed for the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary info

Supplementary Information

Supplementary video

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The images in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the image credit; if the image is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the image. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ramadurgam, S., Yang, C. Semiconductor-Metal-Semiconductor Core-Multishell Nanowires as Negative-Index Metamaterial in Visible Domain. Sci Rep 4, 4931 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04931

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04931

This article is cited by

-

Plasmon response of a metal-semiconductor multilayer 4π-spiral as a negative-index metamaterial

Journal of Nanoparticle Research (2014)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.