Abstract

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) remains a serious cardiovascular disorder across the world. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) codifies a potent immunomodulator and pro-inflammatory cytokine that mediates diverse pathological processes. A promoter 308G>A polymorphism in TNF-α has been implicated in RHD risk. However, the results remain controversial. Therefore, to evaluate more precise estimations of the relationship, a meta-analysis was performed. A total of 7 studies including 735 RHD cases and 926 controls were involved in this meta-analysis. Overall, our results revealed that there was a significant association with RHD risk in three genetic models (homozygous model: OR = 3.06, 95%CI = 1.22–10.60, P = 0.020; dominant model, OR = 2.03, 95%CI = 1.01–4.07, P = 0.048; and recessive model, OR = 4.26, 95%CI = 2.41–7.55, P < 0.001). Further ethnic population analysis found a significantly increased risk of RHD among Asians and Europeans. Interestingly, similar results were found among hospital-based studies. Begg's funnel plot and Egger's test did not reveal any publication bias. Taken together, this meta-analysis demonstrates that the TNF-α 308G>A polymorphism is associated with RHD susceptibility and it contributes to the increased risk of RHD. However, additional well-designed studies with larger samples are warranted to confirm these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is an inflammatory disease of the heart tissue, which seriously affects the quality of life of patients and causes a large economic burden on the national healthcare system1,2. After recovery from the acute stage of carditis, patients developed RHD3. This makes RHD the major acquired heart disease in many developing countries. As a complex disease, the precise molecular mechanism of RHD is still unknown. However, it was widely accepted that the occurrence of RHD relied on the interaction of gene and environment4,5.

Although the pathophysiology has not been fully understood, several lines of evidence suggest that inflammatory response is an essential part of the pathogenesis of RHD6,7. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) is a cytokine that mediates diverse pathological processes, such as shock during infection and inflammation during autoimmunity8,9. Blood mononuclear cell from RHD patients produced more TNF-α than healthy controls10. A common 308G>A polymorphism (rs1800629) in the promoter region of TNF-α has been identified to elicit a regulatory effect on the TNF-α gene. The A allele is associated with increased levels of TNF in plasma compared with the G allele11. Moreover, the 308G>A polymorphism has been shown to contribute to the susceptibility of several autoimmune diseases12,13,14.

Although many studies on the relationship between TNF-α gene 308G>A polymorphism and RHD have been performed so far, the results were still inconsistent15,16,17,18,19,20,21. These disparate findings may be partly due to limited sample size, false positive finding and publication bias. In addition, a previous meta-analysis on this issue also generated conflicting results, which had insufficient power in the meta-analysis22. In the present study, a meta-analysis on all published studies was performed to estimate the overall TNF-α gene 308G>A promoter polymorphism with RHD susceptibility.

Results

Characteristics of Studies

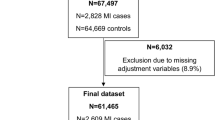

As shown in Figure 1, we identified 89 related articles, of which 7 studies were potentially appropriate. According to the inclusion criteria, a total of 735 cases and 926 controls were available for this analysis. Study characteristics are described in Table 1. Two main genotyping approaches were used, including polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) and PCR-sequence-specific primers (PCR-SSP). Population-based and hospital-based controls were involved in different studies. We also assessed deviation from HWE in controls and the results demonstrated that most genotype distributions among controls were well goodness of fit except for one study18. Of these case-control studies, five reported on Europeans, while two reports were on Asians.

Quantitative synthesis

The A allele frequency of the TNF-α 308G>A polymorphism in Asians and Europeans were 0.055 and 0.156, respectively. The pooled analysis showed that the TNF-α 308G>A polymorphism was significantly associated with RHD risk (homozygous model: OR = 3.06, 95%CI = 1.22–10.60; dominant model, OR = 2.03, 95%CI = 1.01–4.07, Figure 2; and recessive model, OR = 4.26, 95%CI = 2.41–7.55). In the ethnicity-stratified analysis, the significant risk was observed to be associated with recessive model among Asians and Europeans (OR = 7.11, 95%CI = 1.26–40.07 for Asians and OR = 3.92, 95%CI = 2.13–7.21 for Europeans). Moreover, in the stratification of source of controls, significant main effects were found in the hospital-based studies (homozygous model: OR = 6.34, 95%CI = 2.91–31.84; heterozygous model, OR = 1.79, 95%CI = 1.37–2.34; dominant model, OR = 2.29, 95%CI = 1.66–3.16; and recessive model, OR = 4.49, 95%CI = 2.29–10.44) (Table 2).

Test of Heterogeneity, publication bias and sensitivity analysis

There was moderate heterogeneity among all the genetic models except the recessive model (P = 0.626 and I2 = 0.0% in the recessive model). We used funnel plot and Egger's test to access the publication bias of literatures. As shown in Figure 3, the shape of the funnel plots did not show asymmetrical in the dominant model, suggesting absence of publication bias. Moreover, we did not find significant publication bias in the Egger's test (t = 0.07, P = 0.945 in the dominant model). Sensitivity analysis was carried out by removing each study. The pooled ORs were not materially altered (data not shown), implying that the results were robust.

Discussion

TNF-α is produced by macrophages, monocytes, neutrophils, T-cells and NK-cells after stimulation. In turn, TNF-α can stimulate cytokine secretion, increase the expression of adhesion molecules as well as activate neutrophils23,24. TNF-α has been shown to be relevant for the physiopathology of various inflammatory conditions like rheumatic fever, rheumatoid arthritis and RHD25. Furthermore, the TNF-α 308G>A promoter polymorphism has been reported to be associated with high TNF production and this has been associated with increased susceptibility for many inflation diseases26,27. Therefore, it is biologically plausible that the TNF-α 308G>A polymorphism is associated with RHD risk. Compared with the literature by Shen et al.22, we also performed a stratification of ethnic and source of controls in our study, which could explain the difference results among Asians and Europeans. As a result, in the stratified analysis, we found that the main association was pronounced among Asians and Europeans, suggesting that there was no different genetic background contributing to the risk of RHD. However, there was no reported study on African populations. Therefore, additional studies are needed to elucidate the possible ethnic differences in the effect of TNF-α 308G>A polymorphism on RHD risk. Importantly, when stratifying by source of controls, a significantly elevated risk was observed among hospital-based studies but not among population-based studies. This may be due to that the hospital-based case-control studies have some selection biases because such controls might not be a representative of the general population28. Thus, the selection bias and matching criteria should be considered in the design of case-control study.

Some limitations of this meta-analysis should be addressed. First, the ORs extracted from each eligible study were based on unadjusted estimates, because not all studies reported adjusted ORs. Second, the number of each ethnic subgroup was relatively small, which limited the statistical power to detect the association between the TNF-α 308G>A polymorphism and RHD risk among Asians and Europeans. Third, there was significant between-study heterogeneity from studies of the TNF-α 308G>A polymorphism and the genotype distribution also showed deviation from HWE in one study18.

In summary, this meta-analysis of seven case-control studies indicated that the TNF-α 308G>A polymorphism was associated with a significantly increased risk of RHD. These results provided the important role of the TNF-α polymorphisms in the RHD susceptibility and our findings need to be validated by future well-designed large studies.

Methods

Search stagey

A comprehensive literature search was performed using the PubMed database for relevant articles published. The following terms were used in this search: ‘TNF-α or tumor necrosis factor-alpha’ and ‘rheumatic heart disease or RHD’ and ‘polymorphism or polymorphisms’. Additional studies on this topic were identified by contacting the corresponding authors or a hand search of references of related articles. Studies included in the current meta-analysis should meet the following requests: (a) only the case-control studies were considered; (b) evaluated the TNF-α gene 308G>A promoter polymorphism and RHD risk; and (c) had usable reported data on the genotypes among cases and controls.

Data extraction

Information was carefully extracted from all eligible studies independently by two investigators according to the inclusion criteria listed above and the result was reviewed by a third investigator. The following information was extracted from each study: the first author, publication year, country, ethnicity, number of cases and controls, source of controls, genotyping methods and evidence of Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). Different ethnicity descents were categorized as European and Asian. Quality of studies was assessed according to the predefined criteria based on previous observational studies29,30 (Table 3).

Statistical Analysis

Odds ratios (ORs) were used as a measure of the association between the TNF-α 308G>A polymorphism and RHD risk. We evaluated the risk of the AA or GA genotype on RHD compared with the GG genotypes and then calculated the ORs of GA/AA versus GG and AA versus GG/GA, using dominant and recessive genetic models of the A allele, respectively. Pooled estimates of the OR were obtained by calculating a weighted average of OR from eligible study. The between-study heterogeneity I2 was assessed with the Q-test31. Heterogeneity was considered significant if the P < 0.05 among studies. The pooled OR was calculated using the fixed-effects model. Otherwise, the random-effects model was used. The HWE was assessed by Fisher's exact test with significance set at P < 0.05 level. The potential publication bias was constructed by a funnel plot. The funnel plot symmetry was evaluated by using Egger's linear regression test on the natural logarithm scale of the OR and significance was set at P < 0.05 level. All analyses were performed using the Stata software (version 10.0 StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

References

Seckeler, M. D. & Hoke, T. R. The worldwide epidemiology of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Clin Epidemiol 3, 67–84 (2011).

McDonald, M. I. et al. The dynamic nature of group A streptococcal epidemiology in tropical communities with high rates of rheumatic heart disease. Epidemiol Infect 136, 529–39 (2008).

Folger, G. M., Jr, Hajar, R., Robida, A. & Hajar, H. A. Occurrence of valvar heart disease in acute rheumatic fever without evident carditis: colour-flow Doppler identification. Br Heart J 67, 434–8 (1992).

Wang, D. et al. Stroke and rheumatic heart disease: a systematic review of observational studies. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 115, 1575–82 (2013).

Garcia Palmieri, M. R. Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Puerto Rico. A review. Bol Asoc Med P R 60, 330–42 (1968).

Guilherme, L. & Kalil, J. Rheumatic Heart Disease: Molecules Involved in Valve Tissue Inflammation Leading to the Autoimmune Process and Anti- Vaccine. Front Immunol 4, 352 (2013).

Habeeb, N. M. & Al Hadidi, I. S. Ongoing inflammation in children with rheumatic heart disease. Cardiol Young 21, 334–9 (2011).

Apostolaki, M., Armaka, M., Victoratos, P. & Kollias, G. Cellular mechanisms of TNF function in models of inflammation and autoimmunity. Curr Dir Autoimmun 11, 1–26 (2010).

Noti, M., Corazza, N., Mueller, C., Berger, B. & Brunner, T. TNF suppresses acute intestinal inflammation by inducing local glucocorticoid synthesis. J Exp Med 207, 1057–66 (2010).

Miller, L. C. et al. Cytokines and immunoglobulin in rheumatic heart disease: production by blood and tonsillar mononuclear cells. J Rheumatol 16, 1436–42 (1989).

Wilson, A. G., di Giovine, F. S., Blakemore, A. I. & Duff, G. W. Single base polymorphism in the human tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF alpha) gene detectable by NcoI restriction of PCR product. Hum Mol Genet 1, 353 (1992).

Boechat, A. L. et al. The influence of a TNF gene polymorphism on the severity of rheumatoid arthritis in the Brazilian Amazon. Cytokine 61, 406–12 (2013).

Al-Rayes, H. et al. TNF-alpha and TNF-beta Gene Polymorphism in Saudi Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord 4, 55–63 (2011).

O'Rielly, D. D., Roslin, N. M., Beyene, J., Pope, A. & Rahman, P. TNF-alpha-308 G/A polymorphism and responsiveness to TNF-alpha blockade therapy in moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacogenomics J 9, 161–7 (2009).

Hernandez-Pacheco, G. et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha promoter polymorphisms in Mexican patients with rheumatic heart disease. J Autoimmun 21, 59–63 (2003).

Sallakci, N. et al. TNF-alpha G-308A polymorphism is associated with rheumatic fever and correlates with increased TNF-alpha production. J Autoimmun 25, 150–4 (2005).

Chou, H. T. & Tsai, F. J. Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha Gene G-308A and G-238A Polymorphisms are not associated with Rheumatic Heart Disease in Taiwan. Mid-Taiwan Journal of Medicine 11, 150–154 (2005).

Settin, A., Abdel-Hady, H., El-Baz, R. & Saber, I. Gene polymorphisms of TNF-alpha(-308), IL-10(-1082), IL-6(-174) and IL-1Ra(VNTR) related to susceptibility and severity of rheumatic heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol 28, 363–71 (2007).

Ramasawmy, R. et al. Association of polymorphisms within the promoter region of the tumor necrosis factor-alpha with clinical outcomes of rheumatic fever. Mol Immunol 44, 1873–8 (2007).

Mohamed, A. A., Rashed, L. A., Shaker, S. M. & Ammar, R. I. Association of tumor necrosis factor-alpha polymorphisms with susceptibility and clinical outcomes of rheumatic heart disease. Saudi Med J 31, 644–9 (2010).

Rehman, S. et al. A study on the association of TNF-alpha(-308), IL-6(-174), IL-10(-1082) and IL-1Ra(VNTR) gene polymorphisms with rheumatic heart disease in Pakistani patients. Cytokine 61, 527–31 (2013).

Shen, Y. C. et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha polymorphisms and rheumatic heart disease risk: a meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 168, 2878–80 (2013).

Marcotorchino, J. et al. Lycopene attenuates LPS-induced TNF-alpha secretion in macrophages and inflammatory markers in adipocytes exposed to macrophage-conditioned media. Mol Nutr Food Res 56, 725–32 (2012).

Sargi, S. C. et al. Production of TNF-alpha, nitric oxide and hydrogen peroxide by macrophages from mice with paracoccidioidomycosis that were fed a linseed oil-enriched diet. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 107, 303–9 (2012).

Fonseca, J. E. et al. Contribution for new genetic markers of rheumatoid arthritis activity and severity: sequencing of the tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene promoter. Arthritis Res Ther 9, R37 (2007).

Arkwright, P. D. et al. Atopic dermatitis is associated with a low-producer transforming growth factor beta(1) cytokine genotype. J Allergy Clin Immunol 108, 281–4 (2001).

Wilson, A. G., Symons, J. A., McDowell, T. L., McDevitt, H. O. & Duff, G. W. Effects of a polymorphism in the human tumor necrosis factor alpha promoter on transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94, 3195–9 (1997).

Rafailidis, P. I., Bliziotis, I. A. & Falagas, M. E. Case-control studies reporting on risk factors for emergence of antimicrobial resistance: bias associated with the selection of the control group. Microb Drug Resist 16, 303–8 (2010).

Thakkinstian, A., D'Este, C., Eisman, J., Nguyen, T. & Attia, J. Meta-analysis of molecular association studies: vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and BMD as a case study. J Bone Miner Res 19, 419–28 (2004).

Thakkinstian, A. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between {beta}2-adrenoceptor polymorphisms and asthma: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol 162, 201–11 (2005).

Handoll, H. H. Systematic reviews on rehabilitation interventions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 87, 875 (2006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: J.W., Z.R. Performed the experiments: J.W., Z.H., Z.R. Analyzed the data: J.W., Z.H. Contributed reagents/material/analysis tools: J.W., Z.H., Z.R. Wrote the main manuscript text: J.W., Z.H. and Z.R. Reference collection and data management: J.W., Z.R. Statistical analyses and paper writing: Z.R., J.W. Study design: J.W. J.W., Z.H. Prepared figures 1–3: Z.R. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The images in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the image credit; if the image is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the image. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, Rl., Zhang, H. & Jiang, Wl. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha 308G>A polymorphism and risk of rheumatic heart disease: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep 4, 4731 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04731

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04731

This article is cited by

-

Lack of association between the CDH1 polymorphism and gastric cancer susceptibility: a meta-analysis

Scientific Reports (2015)

-

Rheumatic Fever: What is New?

Current Pediatrics Reports (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.