Abstract

Graphene oxide is being used in energy, optical, electronic and sensor devices due to its unique properties. However, unlike its counterpart – graphene – the thermal transport properties of graphene oxide remain unknown. In this work, we use large-scale molecular dynamics simulations with reactive potentials to systematically study the role of oxygen adatoms on the thermal transport in graphene oxide. For pristine graphene, highly ballistic thermal transport is observed. As the oxygen coverage increases, the thermal conductivity is significantly reduced. An oxygen coverage of 5% can reduce the graphene thermal conductivity by ~90% and a coverage of 20% lower it to ~8.8 W/mK. This value is even lower than the calculated amorphous limit (~11.6 W/mK for graphene), which is usually regarded as the minimal possible thermal conductivity of a solid. Analyses show that the large reduction in thermal conductivity is due to the significantly enhanced phonon scattering induced by the oxygen defects which introduce dramatic structural deformations. These results provide important insight to the thermal transport physics in graphene oxide and offer valuable information for the design of graphene oxide-based materials and devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Graphene, a two-dimensional monoatomic carbon sheet1, has attracted tremendous interest due to its unique properties and potential for a wide variety of applications. The reported high thermal conductivity of suspended single layer graphene (1500 to 5800 W/mK)2,3,4,5 is very inspiring, as it provides potential solutions to many technological barriers, such as the increasingly severe heat dissipation problem in microelectronics. Even for supported graphene, Seol et al.6 have reported that the thermal conductivity at room temperature is ~600 W/mK, despite the phonon scattering due to the substrate. For graphene, the ultrahigh thermal conductivity is a combined effect of the large phonon group velocity and long phonon mean free path (MFP). The large group velocity is a result of the strong carbon-carbon bonds and the light carbon atoms. The large phonon MFP is due to the special two-dimensional phonon band structure, which makes satisfying the phonon scattering rules difficult7. This can even make the thermal conductivity divergent7 – a phenomena also observed in other low dimensional systems8,9. Due to the long intrinsic MFPs of some phonons, especially those long wavelength modes, thermal transport can be largely ballistic in pristine graphene depending on its size10. Phonons with intrinsic MFPs longer than the sample characteristic length will travel ballistically while those with intrinsic MFPs smaller than the characteristic length will transfer diffusively. Bae et al.11 observed ballistic to diffusive crossover of heat conductance in graphene ribbons with different sizes.

However, there are many factors that can influence the thermal conductivity of graphene. Real graphene samples usually have grains with sizes ranging from ~O(10) μm to ~O(100) μm12 and the grain boundaries can scatter phonons. However, phonons with MFPs smaller than 10 μm already contribute to a thermal conductivity of over ~3000 W/mK according to calculations7. When supported on substrates, the substrate-graphene interaction strongly scatters the out-of-plane (ZA) flexural modes and thus reduces the thermal conductivity6. Isotopes in graphene also scatter phonons and it has been reported that thermal conductivity of graphene sheets composed of a 50:50 mixture of 12C and 13C is more than 2 times lower than that of the isotopically pure 12C graphene at 320 K13. Such scattering effects also strongly depend on the density and the clustering of isotopes14. Depending on the separation of defects, the phonon scattering process can be phase correlated15 and phonons can even be localized16. Chemical groups, such as hydrogen17,18,19, can also impact thermal conductivity through defect scattering. The thermal conductivity of hydrogenated graphene (referred to as GH in this work) has been studied using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations17,19 and it has been calculated that the thermal conductivity of GH deceases by ~70% when the coverage of hydrogen reaches 30%. Functionalized graphene using patterned C2H12 groups have also been found to have thermal conductivity much lower than pristine graphene due to interface scattering and clamping effects18.

However, lowering the thermal conductivity of graphene is actually of great interest to various applications. For example, the energy conversion efficiency of thermoelectric devices increases as thermal conductivity decreases20. It has been reported that the Seebeck coefficient of a single layer graphene is very high (100 μV/K)6,21,22,23,24,25. As a result, reducing thermal conductivity is important to achieving a high figure of merit, ZT. Similarly, tunable thermal conductivity in nanostructures is another attractive field with a number of great potential applications. It has been experimentally shown that the tuning of oxygen coverage on graphene is reversible26,27, suggesting that not only can oxygen groups be used to decrease the thermal conductivity of graphene, but also that it is possible that the thermal conductivity of oxidized graphene can be actively manipulated.

Despite the extensive studies on thermal conduction in pristine graphene, the thermal transport of this very important derivative of graphene, graphene oxide (GO), has not been studied. Methods have been discovered to produce large-scale graphene from graphene oxide28. However, neither chemical28 nor thermal reduction of oxygen29 can remove oxygen groups from GO completely30. These oxygen groups covalently bind to the graphene surface, making it contain a mixture of sp2 and sp3 hybridized carbon atoms31. Such a feature leads to the special electrical and optical properties of GO26,31,32,33, enabling a wide range of applications in the fields of energy34,35,36,37,38,39,40, electronics41,42,43, optics31,32,44, biosensors45 and photothermal cancer treatment46. The performance and lifetime of many of the above mentioned applications strongly depend on the thermal transport properties of GO, which influence the operating temperatures. As a result, a thorough understanding of how the oxygen groups affect the thermal transport in GO is imperative to applications involving both reduced graphene and GO.

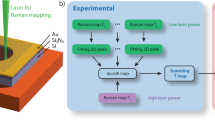

In this work, we use large scale atomistic simulations to systematically investigate the roles of oxygen functional groups (with the focus on epoxy (-O-) group) on thermal transport in the in-plane direction of graphene. We use non-equilibrium molecular dynamics (NEMD) to calculate the thermal conductivity. The interatomic potential used is the reactive empirical bond order (REBO) potential parameterized for C-H-O systems (REBO-CHO)47, which is an expansion of the original REBO potential48,49. The large-scale atomic/molecular massively parallel simulator (LAMMPS)50 is used for all the simulations. More simulation details are discussed in the Method Section and the Supporting Information, Sections 1 and 2.

Results and Discussion

REBO-CHO potential for graphene oxide

To ensure that the REBO-CHO potential can capture the important characteristics of GO, we first validate it by comparing the calculated bond length, binding energy and phonon dispersion relation to those from first-principles density functional theory (DFT) calculations. We study one epoxy group absorbed at the bridge site of a carbon-carbon bond – the most stable site of epoxy group adsorption51 (see Fig. 1a). We minimize the system energy using the REBO-CHO potential and DFT, respectively, to obtain the optimized structures of GO (see Fig. 1a). The calculated binding energy of the epoxy group on graphene using the REBO-CHO potential is within ~11% of the DFT result and the bond length is within 5% (see the table in Fig. 1a).

(a) The optimized structure of GO calculated by DFT and the REBO-CHO potential. The cyan balls represent carbon atoms and the red ball represents an oxygen atom. The table shows the calculated binding energy and bond length of the C-O bond using DFT and REBO-CHO. (b) The phonon dispersion relation of pristine graphene calculated by lattice dynamics using DFT and REBO-CHO. (c) A representative NEMD setup for thermal conductivity calculation. (d) The thermal conductivity of pristine graphene as a function of simulation domain length. Graphene thermal conductivity diverges as ~L0.31 at lengths smaller than 300 nm and diverges as ~L0.10 at lengths larger than 300 nm.

Phonon properties are important to the validity of our study on thermal transport. We use lattice dynamics to calculate the phonon dispersion relation of pristine graphene using the REBO-CHO potential and compare it to DFT results (see Fig. 1b; calculation details are included in the Supporting Information, Section 3). We can see that the acoustic phonons from these two calculations agree well with each other. Although the optical phonons are different, we believe that the REBO-CHO potential can simulate the thermal transport reasonably well in the current study given the correct phonon group velocities of the acoustic phonons which are the dominant heat carriers7,52. The difference in the structures of optical phonons might influence the phase space of the phonon-phonon scattering and thus the intrinsic thermal conductivity of pristine graphene. However, in this study, where defect scattering is expected to dominate the phonon scattering processes, the correctness of acoustic phonons should yield realistic thermal conductivity values. It is worth noting that there are reparameterized potentials for graphene to match the phonon dispersion. However, the interplay between structural properties and thermal transport is important in GO. As a result, the REBO-CHO potential which can capture the structural, binding and phonon properties simultaneously is chosen.

Ballistic thermal transport in graphene

We then use NEMD and the REBO-CHO potential to calculate the thermal conductivity of pristine graphene. For the pristine graphene with a length of L = 20.88 nm in the x-direction (see Fig. 1c), the calculated thermal conductivity is 269.3 W/mK at 300 K, which is in good agreement with previous MD simulations using the REBO potential53. The definition of temperature we employ is the traditional equipartition-based relation. It is worth noting that MD is classical which does not include quantum effects. Relations between total energies expressed as quantum specific heat (based on Bose-Einstein distribution) and classical specific heat (based on Boltzmann distribution) are often employed for correcting quantum effects9,54. If we only consider the specific heat effect, all the thermal conductivity values in this work will be scaled by a same scaling factor, dTmd/dTq, where Tmd is the temperature in the MD simulation and Tq is the quantum counterpart, which will not influence the conclusions in our study. However, the phonon distribution also affects the phonon scattering rates55,56. To make data comparable to experimental results and results from quantum lattice dynamics calculations, both heat capacity and scattering should be corrected in MD simulations. In this work, we do not attempt to correct the quantum effects since the latter is not currently clear.

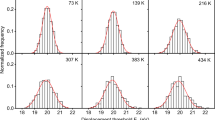

In NEMD simulations, the thermostats imposed at the ends of the sample will scatter phonons artificially and thus limit the phonon MFPs below the sample length. Phonons in graphene have a wide range of MFPs depending on their polarizations and wavelengths. If the intrinsic MFP of a phonon is much larger than the sample length, it can transmit ballistically. As the simulation domain length increases, some long wavelength phonons travel longer distances before scattered at the ends, resulting in an increase in the thermal conductivity57,58,59. We studied the thermal conductivity as a function of the sample length up to L = 3.5 μm. There is an obvious increase in the thermal conductivity as the sample length increases (see Fig. 1d). Even with the sample length increased to 3.5 μm, thermal conductivity is still not converged, suggesting that some portion of the phonons can still travel ballistically in such large samples. This is consistent with the fact that thermal transport in 2D materials is divergent2,3,7.

We further characterized the divergence by fitting the thermal conductivity as a function of length (L) using a power law, κ ∝ Lβ, where β is the divergence power. It is obvious that there are two distinct regions with different β divided by the length of ~300 nm. For graphene with lengths smaller than ~300 nm, the divergence power is 0.31 ± 0.02, which agrees reasonably with the result (0.27 ± 0.02) from a theoretical study on 2D nonlinear lattices, despite the fact that the nonlinear model did not include out-of-plane modes60. As the length of graphene become larger, the divergence power reduces to 0.10 ± 0.02. It is worth noting that the dividing length of ~300 nm agrees well with our extracted effective phonon MFP of ~211 nm using a gray model (see Supporting Information, Section 4). However, since the magnitude of phonon MFPs spans a wide range, not all phonons become diffusive at the same length scale. In short graphene samples, majority of the phonons can have MFPs longer than the sample length and thus divergence power is large. As the sample length becomes longer, more and more phonons become diffusive and the divergence slows down.

If we assume that the thermal conductivity will eventually converge, we can extrapolate to infinite length using the available data59 and we found a thermal conductivity of 925.9 W/mK (see Supporting Information, Section 4, for details). This value falls within the range of other computational results (300–2000 W/mK) from Zhang et al.61 and Khadem et al.62 who used equilibrium MD and the Green-Kubo formula to calculate the thermal conductivity of graphene. Our value is lower than experimental results. This is likely due to the fact that REBO-CHO does not reproduce the optical phonons correctly, which would change the phase space for phonon-phonon scattering and thus change the phonon relaxation time. However, as mentioned earlier, in this study, the oxygen defect scattering is expected to dominate the phonon scattering instead of the phonon-phonon scattering and thus good reproduction of acoustic phonon velocities will yield realistic thermal conductivity values.

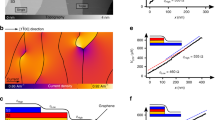

Thermal transport in graphene oxide

We then calculate the thermal conductivity of GO with different oxygen coverages. GO samples with different oxygen coverages are generated by randomly placing oxygen atoms at the bridge sites of pristine graphene. The coverage is defined as the ratio of the oxygen to the carbon atoms. The energy of the GO sample is then minimized using the steepest descent algorithm before it is simulated at 300 K with a constant pressure and constant temperature ensemble (NPT) with the Nose-Hoover method applied for thermostating and barostating. This optimized sample is then used in NEMD to calculate the thermal conductivity (see Method Section and Section 1 in the Supporting Information for more details). With the oxygen atoms attached to the graphene basal plane, the thermal conductivity decreases dramatically with oxygen coverage as shown by the filled red squares in Fig. 2, where the sample length is L = 20 nm and the thermal conductivities are normalized against that of the pristine graphene (κ/κ0). At a coverage of 0.5%, the thermal conductivity is about 53% of that of the pristine graphene, while at a coverage of 20%, the thermal conductivity drops to only about 3% of that of the pristine case.

The relationship between thermal conductivity and the coverage of (a) oxygen adatoms (red line with solid red square); (b) hydrogen adatoms (blue line with solid blue circle); (c) mass defects mimicking oxygen atom weight (red line with open red square); (d) mass defects mimicking hydrogen atom weight (blue line with open blue circle).

Insets show the representative structures from the simulations. Cyan balls represent carbon atoms, red balls represent oxygen atoms and artificial oxygen atoms and blue balls represent hydrogen atoms and artificial hydrogen atoms. The sample length is L = 20 nm for all cases.

According to the solution of the phonon Boltzmann transport equation under the single mode relaxation time approximation63, the thermal conductivity along a particular direction x (κx) can be expressed as:

where v is the phonon group velocity, c is the volumetric heat capacity per mode and l is phonon MFP and the subscript “x” refers to projection along x. k and λ refer to the wavevector and polarization, respectively. For molecular dynamics simulations, the phonon system is in the classical limit and thus the heat capacity per mode is a constant, kB/V, where V is the volume of the primitive cell. Thus the reduction in thermal conductivity is either due to reduction in MFP, reduction in group velocity, or some combination of the two.

In the case of GO, the presence of the oxygen adatoms can influence graphene through either a mass effect (added mass) or a bond deformation effect. Both of these can lead to a change in the local vibrational characteristics and thus an acoustic mismatch that scatters phonons and reduces the phonon MFP. As a comparative study, we calculate the thermal conductivity of “artificial” GO by lumping the masses of the oxygen adatoms to their bound carbon atoms. The masses of the selected carbon atoms are increased by half of the oxygen mass since each oxygen group attaches to two carbon atoms. For such mass-loaded graphene samples, the planar structure is preserved as shown in inset (c) of Fig. 2 and there is a large decrease in the thermal conductivity as the coverage of mass defects increases (open red squares in Fig. 2). We note, however, that the decrease is not as significant as that in the real GO case, which suggests that the deformation of the local bonding environment (see inset (a) in Fig. 2) is important.

The difference between effects of an adatom and a simple mass mismatch is more obvious in hydrogenated graphene (GH). We calculate the thermal conductivity of GH as a function of the hydrogen coverage (filled blue circle in Fig. 2) and compare it to the “artificial” GH with hydrogen mass added to the bound carbon atoms (open blue square in Fig. 2). The mass defects result in much smaller change in the thermal conductivity of the mass-loaded graphene compared to the real GH where the hydrogen adatoms can significantly deform the graphene structures (see insets (b) and (d) in Fig. 2). Comparing the two fictitious samples, it is clear that the larger mass mismatch in the GO can cause a larger reduction in the thermal conductivity – a phenomenon that agrees with the Rayleigh defect scattering picture64. Although the mass mismatch effect in GH is much weaker, we found that the bond deformation in GH is as significant as that in GO (see Section 5 in the Supporting Information for details). As a result, the thermal conductivity reduction in GH and GO are comparable in amplitude.

It is known that the oxidation of graphene leads to the conversion of carbon bonds from sp2 to sp3 bonding30,31,51. Such a change in the local bonding environment alters the dynamics of the carbon atoms as well as the planar structure of the pristine graphene. However, such an effect is not limited to the carbon atoms bound directly to the oxygen groups. We characterized the vibrational dynamics of the carbon atoms near the oxygen groups by calculating the vibrational power spectra (VPS) (see Method Section). The calculation is performed on a GO with one epoxy group to keep the analysis simple (see Fig. 3e). Figure 3a–d show the VPS of the carbon atoms in pristine graphene and those in GO with different distances from the oxygen group. Each VPS is obtained by averaging over all the equivalent carbon atoms.

(a), (b), (c) and (d) show the VPS of carbon atoms in GO with different distances from the oxygen atom and the VPS of the carbon atoms in pristine graphene.The cyan balls represent carbon atoms and the red ball represents an oxygen atom. The table shows the calculated binding energy and bond length of the C-O bond using DFT and REBO-CHO. (b) The phonon dispersion relation of pristine graphene calculated by lattice dynamics using DFT and REBO-CHO. (c) A representative NEMD setup for thermal conductivity calculation. (d) The thermal conductivity of pristine graphene as a function of simulation domain length. Graphene thermal conductivity diverges as ~L0.31 at lengths smaller than 300 nm and diverges as ~L0.10 at lengths larger than 300 nm.The green line in (a) represents the VPS of the carbon atoms that are directly bound to the oxygen atom (green balls in (e)); the blue line in (b) represents the VPS of the carbon atoms that are the second nearest neighbors to the oxygen atom (blue ball in (e)); the purple line in (c) represents the VPS of the carbon atoms that are the third nearest neighbors to the oxygen atom (purple ball in (e)); the red line in (d) represents the VPS of the carbon atoms that are the fourth nearest neighbors to the oxygen atom (red ball in (e)). The black lines in all spectra represent the VPS of the carbon atoms in pristine graphene. (e) The local structure of GO with one epoxy group. The black ball represents the oxygen atom and the green, blue, purple, red and cyan ball represent carbon atoms with different distances from the oxygen atom. The table shows the calculated bond lengths and binding energies of the carbon-carbon bonds in GO, which are normalized against those values in pristine graphene. Bond 1 refers to the bonds between the green and blue balls; bond 2 refers to the bonds between blue and purple balls; bond 3 refers to the bonds between purple and red balls and bond 4 refers to the bonds between red and cyan balls.

We can clearly see that the vibration characteristics of the carbon atoms are altered due to the presence of the oxygen atom (see Fig. 3a–d) and this effect extends to the third nearest neighbors of the oxygen defect (purple balls in Fig. 3e). For the fourth nearest neighbors, the VPS closely resembles that of pristine graphene. The change in VPS leads to a local acoustic mismatch that scatters phonons. It is known that the defect-induced phonon scattering is a strong function of the size of the defects14,65. In GO, the oxygen groups influence the carbon atoms up to the third nearest neighbors, which effectively makes the defects much larger than the adatoms themselves, enhancing the phonon scattering effect.

We characterized the atomic level origins of the VPS change by calculating the bond strength and length of the carbon-carbon bonds around the oxygen atoms, normalized to the data from pristine graphene (see the table in Fig 3e; calculation details can be found in Section 5 of the Supporting Information). We find that the bond energy is reduced and the bond length is elongated for the carbon-carbon bonds immediately next to the oxygen atoms (bond 1 in Fig. 3e). For the bonds next to bond 1 (bond 2 in Fig. 3e), the bond energy is increased and the bond length is reduced. For bond 3 and bond 4 in Fig. 3e, the bond energies and bond lengths converge to those in the pristine graphene, confirming the VPS results which suggest that the influence of the oxygen adatom extends to the third nearest neighboring carbon atoms (purple balls in Fig. 3e). Similar observations are made for GH (see Supporting Information, Section 6). While these observations are based on an isolated oxygen defect, it is worth further noting that at high coverages, the oxygen groups can be close to one another and the deformed regions can overlap, which essentially makes the deformation even larger as shown in inset (a) in Fig. 2. This is expected to further enhance phonon-defect scattering, reducing the phonon MFP and subsequently the thermal conductivity.

It is also noted that the random adsorption of oxygen (hydrogen) atoms on both sides of the graphene plane (see insets (a) and (b) in Fig. 2) can break the reflection symmetry about the graphene plane. According to ref. 7, this will induce more phonon-phonon scattering involving flexural modes and thus decrease the thermal conductivity of GO (GH). We believe that the breaking of the reflection symmetry about the graphene plane in GO (GH) can also contribute to the sharp reduction of the thermal conductivity.

While these analyses show that oxygen defects induce additional phonon scatterings which consequently reduce the phonon MFPs, we also analyze their effects on phonon group velocity which is another factor that could influence the thermal conductivity. To characterize the group velocity of GO with different oxygen coverages, we perform a two-dimensional Fourier transform of the atomic velocities to obtain the phonon spectral energy density and visualize the phonon dispersion relation (see calculation details in the Method Section). Figure 4 shows the phonon dispersion relations of GO with oxygen coverages of 0.5%, 1% and 2.5% (Fig. 4b–c) together with that of pristine graphene (Fig. 4a). We can see that the slopes of acoustic branches of GO (highlighted in red), which are proportional to the group velocities of those modes, are almost identical to those in pristine graphene, suggesting that the absorption of oxygen adatoms does not significantly change the group velocities of acoustic phonons. To verify this statement quantitatively, we extract the average group velocities of the ZA flexural modes – the dominant modes for thermal transport – and found the values to be 4916.2 m/s, 4875.9 m/s, 4863.8 m/s and 4774.4 m/s for pristine graphene and GO with oxygen coverages of 0.5%, 1% and 2.5%, respectively. The changes are less than 3%, which cannot be responsible for the large thermal conductivity reduction observed. The same observation is made for GH (see Supporting Information, Section 7). The line-widths of the spectral energy density peaks, which can be inferred by sharpness of the curves in Fig. 4, are related to phonon lifetimes66. In the contours shown in Fig. 4, the visualized dispersion curves become less sharp as the oxygen coverage increases, meaning that the phonons lifetimes become shorter. As the coverage increases beyond 2.5%, the spectral energy density peaks are so broadened that no clear dispersion curves can be identified and these results are not shown. These observations confirm that it is the phonon-defect scattering, instead of the change in phonon group velocity, that dominates the thermal conductivity reduction in GO.

Quantifying phonon-defect scattering

The above results of GO are obtained from samples with length L = 20 nm. As the sample length becomes longer, longer wavelength phonons can be accommodated. These long wavelength phonons can have different behaviors in defect scattering compared to shorter wavelength phonons. Figure 5a shows the thermal conductivities of GOs with different oxygen coverages as a function of the sample length. Compared to pristine graphene (filled black squares in Fig. 5a), the length effects of the GO thermal conductivity become much less significant when the coverage increases, meaning that the ballistic portion of thermal transport is supressed by defect scattering. For GO with oxygen coverages of 0.5%, 1% and 1.25%, the thermal conductivity increases modestly from L ≈ 20 nm to 80 nm, showing that there are some ballistic phonon transport features below 80 nm. However, the increase in thermal conductivity is much less for L > 80 nm, meaning that the transport has already reached diffusive limit and that defects, instead of the boundaries, dominate phonon scattering in samples with lengths larger than 80 nm. For oxygen coverages of 2.5%, 5% and 15%, the thermal conductivity stays almost constant as the GO length increases from 20 nm to 320 nm, suggesting that with these high oxygen coverages, thermal transport is already fully diffusive in samples with lengths of 20 nm.

(a) The thermal conductivities of GO with different oxygen coverages as functions of sample length.(b) The estimated phonon free path due to defect scattering and average distances between oxygen defects at different oxygen coverages. (c) The thermal conductivities of GO with different lengths as functions of oxygen coverage. The red dashed line indicates the predicted minimal thermal conductivity of pristine graphene at the amorphous limit.

From Fig. 5a, we can see that the thermal conductivities of GO samples are already well converged when their lengths reach 320 nm. The phonon MFP can be approximated using the Matthiessen's rule by combining the effects from different scattering mechanisms:

where l is the effective phonon MFP, lph is the free path due to intrinsic phonon-phonon scattering and ld is the free path due to defect scattering. Combining Eq.s (1) and (2), we can extract ld as a function of the oxygen coverage from the converged thermal conductivities shown in Fig. 5a using the gray model (details shown in the Supporting Information, Section 8). As can be seen in Fig. 5b, ld decreases dramatically from 58.3 nm to 3.6 nm as the oxygen coverage inceases from 0.5% to 20%. As a comparison, we calculated the average distance between oxygen defects (D) as a function of the coverage (η) as:

where A is the area of GO and ncarbon is the total number of carbon atoms (Fig. 5b). We observe that ld values at all coverages are larger than D. This is because phonon-defect scatterings are different for phonons with different wavelengths. It is known that long wavelength phonons – the major contributors to the thermal conductivity in graphene7 – tend to be less suspectible to local defects scattering. As a result, the ld extracted from the gray model is larger than the inter-defect distance. However, as the defect density increases, ld approaches to D, suggesting greater defect scatterings of the whole spectrum of phonons. This is likely related to the more significant structure deformation at higher defect coverages.

Figure 5c shows the same data in Fig. 5a from a different perspective by plotting the thermal conductivity as a function of oxygen coverage for samples with different lengths. We can see that for oxygen coverages below 2.5%, longer GO samples have a higher thermal conductivity, suggesting that some portion of the phonons can still transport ballistically in the length range studied. However, as the oxygen coverage increases, the increasing in thermal conductivity becomes less significant, because the increased defect scattering makes the ballistic portion smaller. As coverage passes 2.5%, strong defect scattering makes phonon transport fully diffusive as suggested by the collapse of the data for different lengths. At a coverage of 5%, the thermal conductivity is clearly sample length-independent and the thermal conductivity is around 28.8 W/mK. At a coverage of 20%, this value is reduced to 8.8 W/mK.

It is usually thought that the lower bound of the thermal conductivity in a solid is the “amorphous limit” which is based on Einstein's model on the random walk of thermal energy67,68,69. This limit is usually thought describing the thermal transport in solid materials with completely disordered atomic morphology. In this amorphous limit, heat carriers are localized and the thermal energy of each atom is transferred to the neighboring sites during one half a period of atomic oscillation. However, with strong phonon scattering due to interfaces, this limit can be broken in layered materials70. For graphene, we calculate this minimal thermal conductivity and find a value of 11.6 W/mK (see Supporting Information, Section 9). Surprisingly, the thermal conductivity of GO with a oxygen coverage of 20%, 8.8 W/mK, beats this amorphous limit. We believe that such an extremely low thermal conductivity is a result of the overlapping of the deformed regions at high oxygen coverages, which makes the scattering processes correlated and thus enhances the overall scattering effects. The correlated scattering is believed to be the reason of the low thermal conductivity found in nanowires which cannot be explained by uncorrelated scattering16.

As mentioned earlier, since the oxygen defect scattering dominates the phonon scattering instead of the phonon-phonon scattering, the good reproduction of acoustic phonon group velocities of the REBO-CHO potential will yield realistic thermal conductivity values. Compared to the measured high thermal conductivity of pristine graphene (1500 to 5800 W/mK)2,3,4,5, oxygen defects with a 20% coverage can reduce the thermal conductivity by 99.4–99.9%. Such a decrease could result in 170–660 times increase in thermoelectric ZT assuming no changes in electrical properties. Of course, adatoms will likely change the electron transport, but the reported high Seebeck coefficient of pristine graphene6,21,22,23,24,25 and the significantly reduced thermal conductivity of graphene through oxidation presented in this work will definitely stimulate further research on the thermoelectric properties.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have found that the thermal conductivity of GO is very tightly related to the coverage of oxygen groups. At a coverage of 0.5%, the thermal conductivity of GO is decreased by ~50% compared to that of pristine graphene. As the coverage increases, the thermal conductivity further decreases and the achieved minimum thermal conductivity of GO is 8.8 W/mK – lower than the predicted minimal thermal conductivity (11.6 W/mK) at the amorphous limit. The results suggest that we can manipulate the thermal transport in graphene through oxidation to reach the two extremes: ballistic limit and amorphous limit. Our spectral analyses indicate that the reduction of thermal conductivity is due to strong defect scattering instead of changes in the phonon group velocities. Atomic level analyses show that the oxygen adatoms alter the local bonding environment of carbon atoms and thus lead to acoustic mismatch, which scatters phonons. The bond deformation makes the effective defect size much larger than the adatom itself and at high coverages, the deformed regions can overlap, which further enlarges the defect size. Also, the breaking of reflection symmetry about graphene plane can be another reason for the reduction of thermal conductivity. The results from this study provide important insight into the thermal transport in GO – an important material for a wide range of applications. The predicted thermal conductivity provides valuable guidance to the design of GO-based composite material and devices, especially the thermal management of GO-based energy, electronic and photonic devices. By actively manipulating oxidation of graphene, the thermal conductivity can be effectively tuned. Considering that the thermal conductivity in nature only spans five orders of magnitude, the tunability displayed by GO is enormous. The significantly reduced thermal conductivity of GO can potentially lead to highly efficient thermoelectric applications.

Methods

Molecular dynamics simulation

We use NEMD to systematically calculate the thermal conductivity of pristine graphene, GO and GH. LAMMPS50 is used for all the simulations. We use the reactive bond order (REBO) potential parameterized for C-H-O systems47, which is an expansion of the original REBO48,49 potential. The REBO-CHO potential has been proven to reproduce the structural properties and binding energies of C-H-O molecules. We have also validated our implementation of the REBO-CHO potential in LAMMPS by successfully reproducing the bond length of some common molecules containing C, H, O atoms (see Table S1 in Supporting Information, Section 3).

We generate the GO and GH samples by randomly placing oxygen and hydrogen atoms on both sides of pristine graphene. The total molecular energies of the GO and GH samples are then minimized using the steepest descent algorithm before it is simulated at 300 K with a constant pressure and constant temperature (NPT) ensemble, which uses Nose-Hoover method71,72 for thermostating/barostatting. During the course of simulation, there can be some hydrogen atoms detaching from the GH samples. These atoms are removed periodically until a steady state coverage is reached. After the optimized structure is obtained, we freeze the atoms at the ends of the structure and run the simulation in a constant volume and constant temperature ensemble (NVT) for 50 ps or 25 ps (the former time is used for pristine graphene and the latter time is used for GO and GH) on the rest of the atoms. We then create a temperature gradient across the simulation supercell by setting the temperatures of the two ends (excluding the fixing atoms) at different values using Langevin thermostats73 and isolated boundary conditions are used in the x-direction. Except the fixed ends, the rest of the atoms are simulated in a constant volume and constant energy ensemble (NVE). Due to the temperature difference, heat flows from the heat source to the heat sink across the sample. Energies added into the heat source and subtracted from the sink are recorded. When steady state is reached, the temperature gradient (dT/dx) is obtained by fitting the linear portion of the temperature profile and heat flux (J) is calculated using J = (dQ/dt)/S, where dQ/dt is the average of the energy input and output rates in the thermostated regions and S is the cross-sectional area. At last, the thermal conductivity (κ) is calculated by Fourier's law, κ = −J/(dT/dx). For the NEMD simulations, a time step of 0.5 fs is used for pristine graphene and 0.25 fs is used for GO and GH calculations. More details of the simulations can be found in the Supporting Information, Section 1.

Vibrational power spectrum

The VPS is calculated by taking the Fourier transform of the autocorrelation of the atomic velocity:

where ω is the frequency, t is the correlation time and  is the velocity autocorrelation function.

is the velocity autocorrelation function.

Spectral energy density

The phonon spectral energy density is computed by taking a two-dimensional Fourier transform of the atomic velocity:

where vα(n, t) is the atomic velocity, ω the frequency, k is the wavevector, n is the index of carbon atoms sorted by the x-coordinate, N is the number of carbon atoms and m is the mass of a carbon atom.

References

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004).

Balandin, A. A. et al. Superior thermal conductivity of single-layer graphene. Nano Lett. 8, 902–907 (2008).

Cai, W. et al. Thermal transport in suspended and supported monolayer graphene grown by chemical vapor deposition. Nano Lett. 10, 1645–1651 (2010).

Chen, S. et al. Raman measurements of thermal transport in suspended monolayer graphene of variable sizes in vacuum and gaseous environments. ACS Nano 5, 321–328 (2011).

Lee, J., Yoon, D., Kim, H., Lee, S. W. & Cheong, H. Thermal conductivity of suspended pristine graphene measured by Raman spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 83, 081419(R) (2011).

Seol, J. H. et al. Two-dimensional phonon transport in supported graphene. Science 328, 213–216 (2010).

Lindsay, L., Broido, D. A. & Mingo, N. Flexural phonons and thermal transport in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 82, 115427 (2010).

Maruyama, S. A molecular dynamics simulation of heat conduction in finite length SWNTs. Physica B 323, 193–195 (2002).

Yang, N., Zhang, G. & Li, B. Violation of Fourier's law and anomalous heat diffusion in silicon nanowires. Nano Today 5, 85–90 (2010).

Muñoz, E., Lu, J. & Yakobson, B. I. Ballistic thermal conductance of graphene ribbons. Nano Lett. 10, 1652–1656 (2010).

Bae, M. H. et al. Ballistic to diffusive crossover of heat flow in graphene ribbons. Nat. Commun. 4, 1734 (2013).

Tahy, K. et al. High field transport properties of 2D and nanoribbon graphene FETs. Device Research Conference, 2009. DRC 2009, 207–208.

Chen, S. et al. Thermal conductivity of isotopically modified graphene. Nat. Mater. 11, 203–207 (2012).

Mingo, N., Esfarjani, K., Broido, D. A. & Stewart, D. A. Cluster scattering effects on phonon conduction in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 81, 045408 (2010).

Prasher, R. Thermal transport due to phonons in random nano-particulate media in the multiple and dependent (correlated) elastic scattering regime. J. Heat Transfer 128, 627–637 (2006).

Murphy, P. G. & Moore, J. E. Coherent phonon scattering effects on thermal transport in thin semiconductor nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 76, 155313 (2007).

Chien, S. K., Yang, Y. T. & Chen, C. K. Influence of hydrogen functionalization on thermal conductivity of graphene: Nonequilibrium molecular dynamics simulations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 033107 (2011).

Kim, J. Y., Lee, J. H. & Grossman, J. C. Thermal transport in functionalized graphene. ACS Nano 6, 9050–9057 (2012).

Pei, Q. X., Sha, Z. D. & Zhang, Y. W. A theoretical analysis of the thermal conductivity of hydrogenated graphene. Carbon 49, 4752–4759 (2011).

Luo, T. & Chen, G. Nanoscale heat transfer - from computation to experiment. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 3389–3412 (2013).

Bao, W. S., Liu, S. Y. & Lei, X. L. Thermoelectric power in graphene. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 22, 315502 (2010).

Dragoman, D. & Dragoman, M. Giant thermoelectric effect in graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 203116 (2007).

Hwang, E. H., Rossi, E. & Das Sarma, S. Theory of thermopower in two-dimensional graphene. Phys. Rev. B 80, 235415 (2009).

Zuev, Y. M., Chang, W. & Kim, P. Thermoelectric and magnetothermoelectric transport measurements of graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 096807 (2009).

Wei, P., Bao, W., Pu, Y., Lau, C. N. & Shi, J. Anomalous thermoelectric transport of Dirac particles in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 166808 (2009).

Ekiz, O. Ö., Ürel, M., Güner, H., Mizrak, A. K. & Dâna, A. Reversible electrical reduction and oxidation of graphene oxide. ACS Nano 5, 2475–2482 (2011).

Hossain, M. Z. et al. Chemically homogeneous and thermally reversible oxidation of epitaxial graphene. Nat. Chem. 4, 305–309 (2012).

Park, S. & Ruoff, R. S. Chemical methods for the production of graphenes. Nat. Nanotech. 4, 217–224 (2009).

Acik, M. et al. Unusual infrared-absorption mechanism in thermally reduced graphene oxide. Nat. Mater. 9, 840–845 (2010).

Bagri, A. et al. Structural evolution during the reduction of chemically derived graphene oxide. Nat. Chem. 2, 581–587 (2010).

Loh, K. P., Bao, Q., Eda, G. & Chhowalla, M. Graphene oxide as a chemically tunable platform for optical applications. Nat. Chem. 2, 1015–1024 (2010).

Gómez-Navarro, C. et al. Electronic transport properties of individual chemically reduced graphene oxide sheets. Nano Lett. 7, 3499–3503 (2007).

Zhang, Y. et al. Direct imprinting of microcircuits on graphene oxides film by femtosecond laser reduction. Nano Today 5, 15–20 (2010).

Stoller, M. D., Park, S., Zhu, Y., An, J. & Ruoff, R. S. Graphene-based ultracapacitors. Nano Lett. 8, 3498–3502 (2008).

Gao, W. et al. Direct laser writing of micro-supercapacitors on hydrated graphite oxide films. Nat. Nanotech. 6, 496–500 (2011).

Yoo, E. et al. Large reversible Li storage of graphene nanosheet families for use in rechargeable Lithium ion batteries. Nano Lett. 8, 2277–2282 (2008).

Liu, Z. et al. Organic photovoltaic devices based on a novel acceptor material: graphene. Adv. Mater. 20, 3924–3930 (2008).

Li, S. S., Tu, K. H., Lin, C. C., Chen, C. W. & Chhowalla, M. Solution-processable graphene oxide as an efficient hole transport layer in polymer solar cells. ACS Nano 4, 3169–3174 (2010).

Zhao, Y., Tang, G. S., Yu, Z. Z. & Qi, J. S. The effect of graphite oxide on the thermoelectric properties of polyaniline. Carbon 50, 3064–3073 (2012).

Xiao, N. et al. Enhanced thermopower of graphene films with oxygen plasma treatment. ACS Nano 5, 2749–2755 (2011).

Eda, G., Fanchini, G. & Chhowalla, M. Large-area ultrathin films of reduced graphene oxide as a transparent and flexible electronic material. Nat. Nanotech. 3, 270–274 (2008).

Eda, G. & Chhowalla, M. Chemically derived graphene oxide: towards large-area thin-film electronics and optoelectronics. Adv. Mater. 22, 2392–2415 (2010).

Wei, Z. et al. Nanoscale tunable reduction of graphene oxide for graphene electronics. Science 328, 1373–1376 (2010).

Eda, G. et al. Blue photoluminescence from chemically derived graphene oxide. Adv. Mater. 22, 505–509 (2010).

Balapanuru, J. et al. A graphene oxide–organic dye ionic complex with DNA-sensing and optical-limiting properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 6549–6553 (2010).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Ultrasmall reduced graphene oxide with high near-infrared absorbance for photothermal therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 6825–6831 (2011).

Ni, B., Lee, K. H. & Sinnott, S. B. A reactive empirical bond order (REBO) potential for hydrocarbon–oxygen interactions. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 16, 7261–7275 (2004).

Brenner, D. W. Empirical potential for hydrocarbons for use in simulating the chemical vapor deposition of diamond films. Phys. Rev. B 42, 9458–9471 (1990).

Brenner, D. W. et al. A second-generation reactive empirical bond order (REBO) potential energy expression for hydrocarbons. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 14, 783–802 (2002).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Yan, J. A. & Chou, M. Y. Oxidation functional groups on graphene: Structural and electronic properties. Phys. Rev. B 82, 125403 (2010).

Nika, D. L. & Balandin, A. A. Two-dimensional phonon transport in graphene. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 24, 233203 (2012).

Ong, Z. Y. & Pop, E. Effect of substrate modes on thermal transport in supported graphene. Phys. Rev. B 84, 075471 (2011).

Lukes, J. R. & Zhong, H. Thermal conductivity of individual single-wall carbon nanotubes. J. Heat Transfer 129, 705–716 (2007).

Broido, D. A., Malorny, M., Birner, G., Mingo, N. & Stewart, D. A. Intrinsic lattice thermal conductivity of semiconductors from first principles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 231922 (2007).

Esfarjani, K. & Chen, G. Heat transport in silicon from first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B 84, 085204 (2011).

Minnich, A. J. et al. Thermal conductivity spectroscopy technique to measure phonon mean free paths. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 095901 (2011).

Wei, Y. et al. The nature of strength enhancement and weakening by pentagon-heptagon defects in graphene. Nat. Mater. 11, 759–763 (2012).

Schelling, P. K., Phillpot, S. R. & Keblinski, P. Comparison of atomic-level simulation methods for computing thermal conductivity. Phys. Rev. B 65, 144306 (2002).

Wang, L., Hu, B. & Li, B. Logarithmic divergent thermal conductivity in two-dimensional nonlinear lattices. Phys. Rev. E 86, 040101 (2012).

Zhang, H., Lee, G., Fonseca, A. F., Borders, T. L. & Cho, K. Isotope effect on the thermal conductivity of graphene. J. Nanomater. 2010, 537657 (2010).

Khadem, M. H. & Wemhoff, A. P. Comparison of Green–Kubo and NEMD heat flux formulations for thermal conductivity prediction using the Tersoff potential. Comp. Mat. Sci. 69, 428–434 (2013).

Chen, G. Nanoscale energy transfer and conversion (Oxford University Press: 2005 January).

Holland, M. G. Analysis of lattice thermal conductivity. Phys. Rev. 132, 2461–2471 (1963).

Slack, G. A. & Hussain, M. A. The maximum possible conversion efficiency of silicon-germanium thermoelectric generators. J. Appl. Phys. 70, 2694–2718 (1991).

Thomas, J. A., Turney, J. E., Iutzi, R. M., Amon, C. H. & McGaughey, A. J. H. Predicting phonon dispersion relations and lifetimes from the spectral energy density. Phys. Rev. B 81, 081411(R) (2010).

Einstein, A. Elementare Betrachtungen uber die thermische Molekularbewe- gung in festen Korpern. Ann. Phys. 35, 679 (1911).

Cahill, D. G. & Pohl, R. O. Lattice vibrations and heat transport in crystals and glasses. Ann. Rev. Phys. Chem. 39, 93–121 (1988).

Cahill, D. G., Watson, S. K. & Pohl, R. O. Lower limit to the thermal conductivity of disordered crystals. Phys. Rev. B 46, 6131–6140 (1992).

Chiritescu, C. et al. Ultralow thermal conductivity in disordered, layered WSe2 crystals. Science 315, 351–353 (2007).

Nose, S. A unified formulation of the constant temperature molecular dynamics methods. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 511–519 (1984).

Hoover, W. G. Canonical dynamics: Equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys. Rev. A 31, 1695–1697 (1985).

Schneider, T. & Stoll, E. Molecular-dynamics study of a three-dimensional one-component model for distortive phase transitions. Phys. Rev. B 17, 1302–1322 (1978).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Notre Dame Center for Research Computing and NSF through XSEDE resources provided by SDSC Trestles and TACC Lonestar under grant number TG-CTS100078. This work is partially funded by the Semiconductor Research Corporation (contract number: 2013-MA-2383) and the startup fund from the University of Notre Dame.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.L. designed simulation and supervised the study and D.G. co-supervised the study. X.M. carried out the simulation. X.M., X.W. and T.Z. analyzed the data. X.M. and T.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors have reviewed, discussed and approved the results and conclusions of this article.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareALike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Mu, X., Wu, X., Zhang, T. et al. Thermal Transport in Graphene Oxide – From Ballistic Extreme to Amorphous Limit. Sci Rep 4, 3909 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03909

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03909

This article is cited by

-

Graphene oxide for photonics, electronics and optoelectronics

Nature Reviews Chemistry (2023)

-

Synthesis and Characteristics of Graphene–Graphene Oxide Material Obtained by an Underwater Impulse Direct Current Discharge

Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing (2023)

-

Molecular modelling of graphene nanoribbons on the effect of porosity and oxidation on the mechanical and thermal properties

Journal of Materials Science (2023)

-

Small molecule additives in multilayer polymer-clay thin films for improved heat shielding of steel

npj Materials Degradation (2022)

-

Formation and characterisation of porous anodized aluminum oxide, synthesized electrochemically in the presence of graphene oxide

Applied Nanoscience (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.