Abstract

SmCo5 based magnets with smaller size and larger maximum energy product have been long desired in various fields such as renewable energy technology, electronic industry and aerospace science. However, conventional relatively rough synthetic strategies will lead to either diminished magnetic properties or irregular morphology, which hindered their wide applications. In this article, we present a facile chemical approach to prepare 200 nm single domain SmCo5@Co core/shell magnets with coercivity of 20.7 kOe and saturation magnetization of 82 emu/g. We found that the incorporation of GO sheets is responsible for the generation of the unique structure. The single domain SmCo5 core contributes to the large coercivity of the magnets and the exchange-coupled Co shell enhances the magnetization. This method can be further utilized in the synthesis other Sm-Co based exchange-coupled magnets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

SmCo5 permanent magnets, with extraordinary magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy about 108 erg/cc as well as high curie temperature over 700°C, have been laying an irreplaceable role in aerospace, motors, electronics and automotive industries. Especially in recent years, the booming development of modern electronics and industries put forward stringent requirement for SmCo5 magnets that they should simultaneously hold smaller size and larger maximum energy product (BH)max1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Fortunately, a size-dependent behavior of ferromagnetism makes it possible. As is well known, the coercivity of a single crystalline permanent magnet increases with the reduction of grain size from multi-domain range to critical single domain size and then decreases for smaller grain6,8,9. Therefore, single domain SmCo5 magnets are believed to have a good chance possessing superior ferromagnetic performance than commercial bulk SmCo5 magnets10,11,12,13,14,15. Zhang and co-workers synthesized 7 nm single domain Sm-Co NPs with controlled size and composition via reductive annealing of CaO-coated Sm-Co oxide NPs14. However, those NPs were so minute that they not only held diminished ferromagnetic properties (coercivity = 7.2 kOe) but also endured easily oxidation. On the other hand, Hadjipanayis and co-workers prepared single domain SmCo5 particles with average size from 176 nm to 376 nm by mechanochemical method16. Though the particles have wide size distribution, the coercivity of the magnets can reached up to 23.7 kOe with increase of the average size to 300 nm, which is comparable to commercial SmCo5 magnets.

Another route to produce minimized magnets with enlarged (BH)max lies in the exchange coupling of magnetically hard and soft phases in magnets. It is accepted that rare earth based exchange-coupled magnets might be next generation of permanent magnets which hold larger maximum energy product with less use of rare-earth elements17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. Liu and co-workers synthesized nanostructured Sm-Co/Fe bulk magnets by warm compaction method and found that the (BH)max of products increased from 10 to 17 MG·Oe with the contents of Fe increase from 0 to 25%18. In addition, they fabricated sintered Sm-Co/Fe magnets with (BH)max of 18 MG·Oe27,28 and further manifested that the formation of intermediate layer by interphase diffusion of Co and Fe is the origin of enhanced energy product21,24,28,29,30,31,32. Similarly, Skomski and co-workers also implied the importance of interphase layers to the single-phase like behavior of the SmCo5 based magnetic composite33.

Despite the significant progress in the two strategies mentioned above, it is still an arduous task to prepare desired SmCo5 magnets due to the obstacles in controlled synthesis of highly ferromagnetic single domain SmCo5 magnets as well as hardship in introducing both effectively exchange-coupled soft phases and uniform interphase layers.

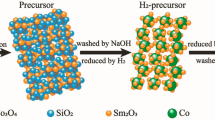

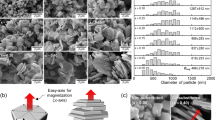

Herein, we report a bottom-up method to chemically synthesize exchange-coupled single domain SmCo5@Co core/shell magnets with an amorphous interphase layer by reductive annealing of Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O@graphene oxide particles. The as-synthesized SmCo5@Co magnets have an average size of 200 nm and exhibit enhanced coercivity of 20.7 kOe and saturation magnetization of 82 emu/g. In our strategy, graphene oxide (GO) sheets played a vitally important role in the fabrication of the mesoscopic high performance magnets. During the preparation of precursor, the wrapping of GO sheets restrained the growth of Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O crystals so that the size of resulted Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O@GO particles would meet the requirement for production of 200 nm SmCo5@Co magnets. Afterwards, during the high temperature reduction reaction, GO sheets helped to sustain the SmCo5 particles as single crystals, which is a fundamental requirement for the formation of single domain magnets. Besides, by controlling the interphase diffusion during the annealing process, GO sheets also facilitated the generation of Co shell and interphase layer which increased saturation magnetization and promoted exchange coupling effect in the magnets, respectively.

Results

Morphology and structure of Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O@GO precursor

Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O crystals were prepared by a slow crystallization procedure and exhibited slight yellow color (Figure S1a). The structure analysis revealed that the crystals have orthorhombic structure with a space group of Cmcm (Figure S2)34,35. In the structure, the Sm3+ (green) and Co3+ (blue) were stacked along y-axis alternately and were connected with each other through a -(CN)- bridging, which made the uniform dispersion of Sm and Co in Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O crystals. However, the crystal would grow to a large size of several millimeters without restraint, which is not favorable for the subsequent synthesis of minimized SmCo5@Co magnets. GO sheets will properly solve this issue. With the incorporation of GO, Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O would nucleate and grow on GO sheets and GO sheets would in turn wrap on the surface of the crystals and inhibit the growth of crystals to larger size. TEM images showed that Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O@GO particles have pencil like shape with average diameter of 2 μm and length of 8 μm (Figure 1a). A TEM image of particle fringe (indicated by the red square in Figure 1a) was presented in Figure 1b. In the image, the interphase between crystal and GO sheets was suggested by the dot line and the Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O crystal was well enfolded by GO sheets. As the result of coherently well wrapping of GO sheets, the as-prepared Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O@GO exhibited a monochromatic brown color (Figure S1b–d).

Morphology and structure of single domain SmCo5@Co magnets

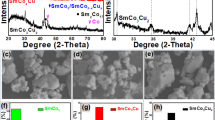

SmCo5@Co magnets were prepared by a reductive annealing process of Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O@GO as precursor. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was used to characterize the chemical structure of the product (Figure 2a). The XRD pattern matched well with standard SmCo5 either in the position or in the intensity of the peaks (JCPDS No. 27-1122), indicating the formation of SmCo5 phase. A small peak at 44° corresponded to the standard pattern of cubic Co (JCPDS No. 15-0806) indicates the co-existence of cubic Co along with a dominant SmCo5 phase. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was then utilized to look into the morphology of the products. According to the TEM images, instead of generating bulk magnets or agglomerated particles with random size and morphology, the products were consisted of 200 nm isolated particles (Figure 2b, c). High resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images further manifested the detailed configuration of the as-synthesized particles. Figure 2d is the edge structure of a typical particle as shown in Figure 2c. From the HRTEM image, it can be seen that the exterior part of the particle had several nanocrystalline domains and the lattice spacing values of 0.180 nm and 0.201 nm are close to the inter-plane distance of 0.177 nm and 0.205 nm in the [111] planes and [200] planes in cubic Co (JCPDS No. 15-0806), respectively. This observation implies the external part of the particle is composed of polycrystalline Co phase. Then, closed to the exterior Co shell, a coherent amorphous layer with thickness of 2 nm was observed as marked by the dot lines in Figure 2d. Based on previous study, such intermediate layer was formed by interphase diffusion between soft and hard phase during high temperature process and would enhance the exchange-coupled effect as well as sustain the integrality of hard phase by blocking excessive diffusion21,24,28,29,30,31,32. In the interior part, as shown in Figure 2d, the lattice fringes were all along the same direction, which demonstrates the single crystalline nature of the inside part. The lattice spacing value of 0.210 nm fitted well to the interplane distance of 0.212 nm in [111] planes in hexagonal SmCo5. HRTEM image of an arbitrary interior part also exhibited concordant parallel fringes with a lattice spacing value of 0.210 nm, which suggests the core of the particle as single crystalline SmCo5 (Figure 2e). In addition, selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern of the particle with hexagonal symmetric diffraction spot further proves the generation of single crystalline SmCo5. Considering the single crystalline nature as well as a diameter smaller than critical size of single domain of SmCo5 (~0.7 μm), the interior part is determined as single domain SmCo5. Magnetic force microscopy (MFM) images also demonstrate the single domain structure in SmCo5@Co particles (Figure S3a, b). According to the image, magnetic moments were all along the same direction and no domain wall structure could be found. Consequently, the as-synthesized magnets (200 nm) possess a multi-grain Co shell and single domain SmCo5 core with an amorphous intermediate layer. Note that the interaction with the lattice of Sm-Co matrix might be responsible for the formation of metastable cubic Co36,37,38,39.

(a) XRD pattern of as-synthesized SmCo5@Co magnets. The black lines are the standard diffraction pattern of SmCo5 (JCPDS No. 27-1122) and the green lines are the standard diffraction pattern of Co (JCPDS No. 15-0806).(b) TEM image of as-synthesized SmCo5@Co magnets. (c) TEM image of an isolated SmCo5@Co particle. (d) HRTEM image of the exterior part of SmCo5@Co particle. (e) HRTEM image of an arbitrary interior part of the particle. (f) SAED pattern of the SmCo5@Co particle shown in c).

To further investigate the structure of products described above, element analysis by a scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) along with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) line scan was performed (Figure 3). From the STEM image (Figure 3a), the particles had average size of 200 nm, which are in good agreement with the TEM observation. The EDS line scan was applied on the edge of the particle as indicated by the red dot line in the inset of Figure 3a. Note that the inset is an amplified image of the blue box in Figure 3a and the scale bar represents 5 nm. The profile of the line scan was displayed in Figure S4 and four points (denoted by b, c, d and e in Figure 3a) were picked to present the distribution of chemical composition in detail. The corresponding EDS patterns of the selected four points were shown in Figure 3b–e, respectively. In the EDS patterns, only Co was detected in external points (Figure 3b–c) while both Sm and Co were observed in the relatively internal point (Figure 3e), which confirm the formation of SmCo5@Co core/shell magnets. In addition, EDS scan of an area of the sample suggests that the Co content in the SmCo5@Co magnets is 4%. Thus, the overall schematic illustration for the fabrication of SmCo5@Co magnets was displayed in Figure 4.

Magnetic properties of single domain SmCo5@Co magnets

Physical property measurement system (PPMS) was used to characterize the room temperature magnetic properties of SmCo5@Co particles (Figure 5). The magnets exhibited a saturated magnetization of 82 emu/g with a remnant magnetization of 62 emu/g (the inset of Figure 4), which defines Mr/Ms ratio of the as-synthesized magnets as 0.75, verifying the effective exchange-coupling between hard and soft phases. Moreover, the magnets have a room temperature coercivity of 20.7 kOe, which is so far one of the largest room temperature coercivity obtained from chemical synthesized SmCo5 based magnets with such size to the best of our knowledge11,40. The enhanced coercivity is originated from the 200 nm single domain SmCo5 core and the large saturation magnetization is attributed to the exchange-coupled effect between SmCo5 and Co. In addition to that, according to the B-H hysteresis loop, the magnets held a superior (BH)max of 10 MG·Oe, which is comparable to bulk SmCo5 magnets prepared from sintered or warm compaction methods (Figure S6)2.

Discussion

The incorporation of GO sheets has great impact on the generation of SmCo5@Co magnets. To demonstrate the importance of GO sheet, Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O crystals without GO wrapping were directly utilized as the precursor and underwent the same procedure as the synthesis of SmCo5@Co particles. The XRD pattern of the product fitted well with the standard SmCo5 pattern (JCPDS No. 27-1122) (Figure 6a), suggesting the formation of SmCo5 phase. Additionally, an unknown peak appeared at 43° might be conducted by defects or lattice mismatch from Sm evaporation. TEM image of the product implies that the as-prepared particles were severely aggregated and had irregular shapes as well as random sizes ranging from 100 nm to 600 nm (Figure S5a). HRTEM images indicate the microstructures of the particles. As shown in Figure 6b, there was neither a core/shell structure nor an amorphous layer existed in the exterior part. Instead, assembly of SmCo5 nanocrystals was found as marked by the dot circles in Figure 6. The lattice spacing value of 0.241 nm and 0.221 nm corresponded to [110] and [200] planes of SmCo5, respectively (JCPDS No. 27-1122). HRTEM image of the interior part showed a similar structure as the outer part. As can be seen in Figure 6c, the inner part was also consisted by nanosized grains and the lattice spacing value of 0.210 nm and 0.247 nm fitted well with inter-plane spacing of [111] and [110] planes of SmCo5, respectively (JCPDS No. 27-1122). SAED of an isolated as-synthesized particle shown in Figure S5b further supports the result from HRTEM images (Figure 6d). A ring pattern in the SAED indicates the constitution of random-orientated nanocrystalline SmCo5 grains within the structure41. Furthermore, MFM image, which showed an array of alternative domains in the magnet, also proves the product as multi-domain SmCo5 magnets (Figure S3b, c). Consequently, the as-synthesized SmCo5 particles present deteriorative (BH)max of 3 MG·Oe with coercivity of 13.7 kOe and saturation magnetization of 58 emu/g (Figure 6e and S6).

(a) XRD pattern of as-synthesized SmCo5 particles. The black lines are the standard diffraction pattern of SmCo5 (JCPDS No. 27-1122). (b) HRTEM image of the edge of SmCo5 particle. (c) HRTEM image of an arbitrary interior part of the particle. (d) SAED pattern of a single SmCo5 particle shown in Figure S5b. (e) Room temperature hysteresis loop of multi-domain SmCo5 particles.

Thus, during the high temperature annealing process, GO sheets have at least three indispensable contributions to the generation of highly ferromagnetic single domain SmCo5@Co magnets. Firstly, GO sheets will restrain the growth of particles and confine the size of magnets to 200 nm. In a meantime, they also impede inter-particle fusion, which facilitates the production of isolated particles. Secondly, wrapping of GO sheets will help to sustain magnetic hard phase as single crystalline during collapse of -(CN)- bridge and formation of SmCo5 under high temperature treatment. Finally, GO sheet seems to obstruct interphase diffusion of Co so that Co shell along with an amorphous intermediate layer are deposited and formed on the surface of SmCo5 hard phase.

The Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O@GO can be also employed to synthesize a series of SmCo5 based magnets. By increasing Co/Sm ratio from 3.5 to 3.7 in the starting material, as can be seen in Figure S7b, the intensity for the reflection of Co phase was increased while a small peak for the [303] plane of Sm2Co17 appeared, which is the peak with maximum intensity in the standard pattern of Sm2Co17 (JCPDS No. 19-0359). Moreover, after increasing Co/Sm ratio to 4 in the starting material, the reflection peaks of Sm2Co17 phase arose in the XRD pattern of the product as indicated by the solid triangles in Figure S7c and an amount of 9% Sm2Co17 was converted with referring to the EDS result. We used EDS line scan along with HRTEM to look into the detailed structure of the SmCo5@9% Sm2Co17 magnets. Figure S8a is the scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) image of the magnets, while Figure S8b and S8c are the corresponding profiles of the scan line 1 and 2 in Figure S8a, respectively. According to the profiles, the exterior part of resulted magnets had larger Co/Sm ratio while interior part had a comparatively smaller Co/Sm ratio, which implies the formation of SmCo5@Sm2Co17 core/shell structure. The HRTEM image as shown in Figure S8d also proves the generation of core/shell structure, the exterior part of the particle had several nanocrystalline domains and the lattice spacing values of 0.207 nm and 0.204 nm were close to the inter-plane distance of 0.208 nm and 0.204 nm in the [303] planes and [214] planes in Sm2Co17, respectively. Meanwhile, in the interior part, the lattice fringe were all along the same direction and the lattice spacing value of 0.251 nm fitted well to the inter-plane distance of 0.250 nm in [110] planes in SmCo5 (JCPDS No. 27-1122). Therefore, similar with that in SmCo5@Co magnets, the magnets have a single crystalline SmCo5 core and multi grain Sm2Co17 shell. This suggests that, with further addition of Co source, the formation of SmCo5@Co magnets with larger content of Co phase is not preferred in our experiment, but Sm2Co17 phases readily generate on the exterior part of the magnets.

When we further increased the Co/Sm ratio to 4.3, 5 and 5.5 in the starting material, as shown in Figure S9, 17%, 40% and 51% Sm2Co17 were observed in the generated magnets, respectively. We took SmCo5@40% Sm2Co17 as an example to manifest detailed structures of magnets with larger content of Sm2Co17. Figure S10a is the scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) image of the magnet, while the EDS profiles in Figure S10b and S10c correspond to the scan line 1 and 2 in Figure S10a. Based on the profiles, similar with SmCo5@9% Sm2Co17 magnets, the exterior part of the produced magnet had larger Co/Sm ratio while interior part held a smaller Co/Sm ratio, which suggests the presence of SmCo5@Sm2Co17 core/shell structure. HRTEM analysis was performed on the edge of the magnet (Figure S10c). According to the HRTEM image, in the exterior part, the magnet had an apparently thicker shell than that of SmCo5@9% Sm2Co17 magnets and the lattice spacing values of 0.189 nm and 0.209 nm are close to the inter-plane distance of 0.187 nm and 0.210 nm in the [223] planes and [220] planes in Sm2Co17 (JCPDS No. 19-0359), respectively. In the interior part, the lattice fringe pattern exhibited single crystalline nature and the lattice spacing value of 0.212 nm fitted well to the inter-plane distance of 0.212 nm in [111] planes in SmCo5 (JCPDS No. 27-1122). Thus, with increase of Sm2Co17 content in the product, the as-synthesized SmCo5@40% Sm2Co17 magnets have thicker Sm2Co17 shell while the interior part still hold single crystalline SmCo5 core.

Demagnetization curves of as-prepared magnets with different composition were shown in Figure 7. The curves show that all the magnets exhibited single-phase demagnetization behavior. Moreover, with the increase of Sm2Co17 amount in the magnets, the coercivity of magnets decreases from 20.7 kOe to 7.1 kOe while the saturation magnetization increased from 82 to 114 emu/g. Table 1 summarized magnetic properties of as-synthesized SmCo5 magnets with various compositions.

Interestingly, Sm2Co17@Co magnets can be also prepared by tuning the Co/Sm molar ratio to 7 in the starting materials. According to the XRD results, the peaks of resulted magnets matched well with the standard patterns of Sm2Co17 (JCPDS No.19-0359) and Co (JCPDS No. 15-0806) (Figure s11a), indicating the co-existence of Sm2Co17 and Co. HRTEM image of the edge of a random particle was shown in Figure S11b. Similar with what was founded in SmCo5@Co, the HRTEM image also manifests that the outer layer was composed of multi-domain outer shell and inner part is formed by single crystalline core. In addition, the lattice spacing value of 0.205 nm in the inner part matched well with inter-plane distance of 0.205 nm in the [200] planes of Co (JCPDS No. 15-0806) while the lattice spacing value of 0.210 nm in the outer part was consistent with inter-plane distance of 0.209 in the [220] planes in Sm2Co17 (JCPDS No. 19-0359). Therefore, Sm2Co17@Co magnets were also synthesized from Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O@GO precursor. Moreover, based on PPMS characterization, the as-synthesized Sm2Co17@Co magnets exhibited favorable room temperature coercivity of 5.7 kOe and saturation magnetization of 124 emu/g (Figure S11c).

In summary, we developed a facile route to synthesize core/shell structured single domain SmCo5@Co magnets with size of 200 nm via a reductive annealing of Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O@GO precursor. The as-synthesized SmCo5@Co particles exhibited enhanced (BH)max with large coercivity and saturation magnetization. We found that the GO sheets played a vitally important role in the generation of single domain SmCo5 phase as well as the core-shell structure. In addition, this strategy can be extended to the synthesis of the SmCo5 based magnets with different contents Sm2Co17 as well as Sm2Co17@Co magnets upon the increase of Co contents in the starting materials. This work provides a facile and promising approach to the preparation of miniaturized rare-earth magnets with highly ferromagnetic performance and other intermetallic magnets.

Methods

In a typical procedure of synthesizing SmCo5@Co magnets, Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O@GO particles were used as precursor and cobalt acetylacetonate (Co(acac)2) fine powder was added to tune the Co/Sm molar ratio. Moreover, Ca and KCl were applied as reducing agent and high temperature solvent, respectively.

Synthesis of Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O crystals

0.7 g (2 mmol) K3[Co(CN)6] (95%) and 0.89 g (2 mmol) Sm(NO3)3·6H2O (99.95%) were each dissolved in 5 ml DI water. 0.4 ml 6.5% (volume ratio) HNO3 was added to K3[Co(CN)6] solution. The K3[Co(CN)6]/HNO3 solution was added dropwise into Sm(NO3)3 solution. Then, the mixture was kept without disturbing for 7 days until the generation of yellow crystals. Finally, the crystals were washed with DI water for 3 times and dried.

Synthesis of Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O@GO particles

GO was prepared from graphite powder by a modified Hummers method. 80 mg of the GO was exfoliated in 80 ml DI water by sonication for 1 h to generate GO sheets. The GO sheet were collected and dispersed again in 5 ml DI water. Then, 0.89 g (2 mmol) Sm(NO3)3·6H2O (99.95%) was added into the GO solution and the mixture were shaked for 1 h. 0.7 g (2 mmol) K3[Co(CN)6] (95%) was dissolved in 5 ml DI water and 0.4 ml 6.5% (volume ratio) HNO3 was added to K3[Co(CN)6] solution. Following that, the K3[Co(CN)6]/HNO3 solution was added dropwise into as-prepared Sm(NO3)3/GO mixture. The system was kept without disturbing for 7 days until the generation of coherently brown resultant. Finally, the resultant was washed with DI water for 3 times and dried.

Synthesis of single domain SmCo5@Co and Sm2Co17@Co magnets

300 mg Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O@GO was mixed with 441 mg Co(acac)2 fine powder (99.5%), 800 mg Ca powder and 500 mg KCl (Co/Sm ratio = 3.5) under Ar atmosphere. The mixture was transferred in a stainless boat with cap. The stainless boat was then moved to a corundum tube. After that, the tube was degassed under 120°C for 1 h to remove air and moisture. Subsequently, the tube was flushed with Ar and heated to 960°C at a rate of 20°C min−1. The reaction was held at 960°C for 30 min before cooled down to room temperature. The resultant was washed with degassed DI water and 0.5% acetic acid to dissolve CaO, KCl and extra Ca. Finally, the powder was dried under vacuum for further characterization. SmCo5@9% Sm2Co17, SmCo5@17% Sm2Co17, SmCo5@40% Sm2Co17, SmCo5@51% Sm2Co17 and Sm2Co17@Co magnets were prepared by the same method with a Co/Sm ratio of 4, 4.3, 5, 5.5 and 7 in the starting materials.

Synthesis of multi-domain SmCo5 magnets

300 mg Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O was mixed with 353 mg Co(acac)2 fine powder (99.5%), 800 mg Ca powder and 500 mg KCl (Co/Sm ratio = 3) under Ar atmosphere. The mixture was transferred in a stainless boat with cap. The stainless boat was then moved to a corundum tube. After that, the tube was degassed under 120°C for 1 h to remove air and moisture. Subsequently, the tube was flushed with Ar and heated to 960°C at a rate of 20°C min−1. The reaction was held at 960°C for 30 min before cooled down to room temperature. The resultant was washed with degassed DI water and 0.5% acetic acid to dissolve CaO, KCl and extra Ca. Finally, the powder was dried under vacuum for further characterization.

Characterization

X-ray Crystallography measurement of Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O were made on a Rigaku RAXIS-IV image plate area detector with graphite monochromated Mo Kα radiation. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was taken on an FEI Tecnai T20 microscope. High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) and EDS line scan were carried out on an FEI Tecnai F30 microscope. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were obtained using a Rigaku DMAX-2400 X-ray diffractometer equipped with Cu Kα radiation. The accelerating voltage and current were 40 kV and 100 mA, respectively. The magnetic properties were measured on a Quantum Design PPMS 9 Tesla system. MFM images were taken on a VEECO Nanonscope IIIa microscopy.

References

Yang, C. & Hou, Y. L. Advance in the chemical synthesis and magnetic properties of nanostructured rare-earth-based permanent magnets. Rare Metals 32, 105–112 (2013).

Poudyal, N. & Liu, J. P. Advances in nanostructured permanent magnets research. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 46, 043001 (2013).

Willard, M. A., Daniil, M. & Kniping, K. E. Nanocrystalline soft magnetic materials at high temperatures: A perspective. Scripta Mater. 67, 554–559 (2012).

Balamurugan, B., Sellmyer, D. J., Hadjipanayis, G. C. & Skomski, R. Prospects for nanoparticle-based permanent magnets. Scripta Mater. 67, 542–547 (2012).

Chaubey, G. S., Poudyal, N., Liu, Y. Z., Rong, C. B. & Liu, J. P. Synthesis of Sm-Co and Sm-Co/Fe nanocrystals by reductive annealing of nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 509, 2132–2136 (2011).

Majetich, S. A. & Jin, Y. Magnetization directions of individual nanoparticles. Science 284, 470–473 (1999).

Gutfleisch, O. et al. Magnetic Materials and Devices for the 21st Century: Stronger, Lighter and More Energy Efficient. Adv. Mater. 23, 821–842 (2011).

Giri, A., Chowdary, K. & Majetich, S. A. Hard magnetic nanoparticles and nanocomposites. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. P 577, 197–207 (1999).

Bachmann, K., Bischofb, A. & Hofer, F. Magnetic Domain Patterns in Small Single Crystal SmCo5 Particles. J. Mater. Sci. 6, 169–& (1971).

Hou, Y. L. et al. A facile synthesis of SmCo5 magnets from Core/Shell Co/Sm2O3 nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 19, 3349–3352 (2007).

Chen, C. H. et al. The effect of particle size on coercivity and crystallinity of SmCo5 . Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 012504 (2011).

Liu, J. P. Ferromagnetic nanoparticles: Synthesis, processing and characterization. JOM 62, 56–61 (2010).

Poudyal, N., Rong, C. B. & Liu, J. P. Effects of particle size and composition on coercivity of Sm-Co nanoparticles prepared by surfactant-assisted ball milling. J. Appl. Phys. 107, 09A703 (2010).

Zhang, H. W. et al. Chemical synthesis of hard magnetic SmCo nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 16873–16876 (2011).

Wang, Y. P., Li, Y., Rong, C. B. & Liu, J. P. Sm-Co hard magnetic nanoparticles prepared by surfactant-assisted ball milling. Nanotechnology 18, 465701 (2007).

Zheng, L. Y. et al. Core/shell SmCo5/Sm2O3 magnetic composite nanoparticles. J. Nanopart. Res. 14, 1129 (2012).

Liu, W. et al. Exchange couplings in magnetic films. Chinese Phys. B 22, 027104 (2013).

Rong, C. B. et al. High temperature magnetic properties of SmCo5/alpha-Fe(Co) bulk nanocomposite magnets. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 152401 (2012).

Hu, D. W. et al. Structure and magnetic properties of bulk anisotropic SmCo5/alpha-Fe nanocomposite permanent magnets prepared via a bottom up approach. J. Alloys Compd. 538, 173–176 (2012).

Hou, Y., Sun, S., Rong, C. & Liu, J. P. SmCo5/Fe nanocomposites synthesized from reductive annealing of oxide nanoparticles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 153117 (2007).

Choi, Y. et al. Controlled interface profile in Sm-Co/Fe exchange-spring magnets. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 072509 (2007).

Choi, Y. et al. Role of diffused Co atoms in improving effective exchange coupling in Sm-Co/Fe spring magnets. Phys. Rev. B 75, 104432 (2007).

Zhang, J., Takahashi, Y. K., Gopalan, R. & Hono, K. Sm(Co,Cu)5/Fe exchange spring multilayer films with high energy product. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 122509 (2005).

Yu, M. H. et al. Interphase exchange coupling in Fe/Sm-Co bilayers with gradient Fe thickness. J. Appl. Phys. 98, 063908 (2005).

Fullerton, E. E. et al. Structure and magnetic properties of exchange-spring Sm-Co/Co superlattices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 72, 380–382 (1998).

Kneller, E. F. & Hawig, R. The Exchange-Spring Magnet - a New Material Principle for Permanent-Magnets. Ieee Trans. Magn. 27, 3588–3600 (1991).

Rong, C. B. et al. Bulk SmCo5/alpha-Fe nanocomposite permanent magnets fabricated by mould-free Joule-heating compaction. J. Appl. Phys. 109, 07A735 (2011).

Xiong, X. Y. et al. Atom probe study on the bulk nanocomposite SmCo/Fe permanent magnet produced by ball-milling and warm compaction. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 323, 2855–2858 (2011).

Liu, Y. Z. et al. Microstructure analysis of a SmCo/Fe exchange spring bilayer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 192502 (2008).

Wu, D. X., Zhang, Q. M., Liu, J. P. & Sabirianov, R. F. Dependence of exchange coupling on interfacial conditions in SmCo5/Co system: A first-principles study. J. Nanosci. Nanotechno. 8, 3036–3039 (2008).

Zhang, Y., Kramer, M. J., Rong, C. B. & Liu, J. P. Microstructure and intergranular diffusion in exchange-coupled Sm-Co/Fe nanocomposites. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, (2010).

Rong, C. B., Zhang, Y., Kramer, M. J. & Liu, J. P. Correlation between microstructure and first-order magnetization reversal in the SmCo5/alpha-Fe nanocomposite magnets. Phys. Lett. A 375, 1329–1332 (2011).

Zhou, J. et al. Rapidly annealed exchange-coupled Sm-Co/Co multilayers. J. Appl. Phys. 97, 10K304 (2005).

Gramlich, V., Petter, W. & Hulliger, F. The Space Group of the Structure of ErFe(CN)6·4H2O and Its Analogs LnT(CN)6·4H2O (Ln = Sm…Lu, T = Fe, Cr, Co). Acta Crystallogr. C 46, 724–726 (1990).

Wickleder, M. S. Inorganic lanthanide compounds with complex anions. Chem. Rev. 102, 2011–2087 (2002).

Liu, B. L. et al. High temperature selective growth of single-walled carbon nanotubes with a narrow chirality distribution from a CoPt bimetallic catalyst. Chem. Commun. 48, 2409–2411 (2012).

Chen, S. K., Tsai, J. L. & Chin, T. S. Nanocomposite Sm2Co17/Co permanent magnets by mechanical alloying. J. Appl. Phys. 79, 5964–5966 (1996).

Ciotonea, C. et al. Nanosized transition metals in controlled environments of phyllosilicate-mesoporous silica composites as highly thermostable and active catalysts. Chem. Commun. 49, 7665–7667 (2013).

Seo, K. et al. Diffusion-Driven Crystal Structure Transformation: Synthesis of Heusler Alloy Fe3Si Nanowires. Nano Lett. 10, 3643–3647 (2010).

Ge, J. P., Hu, Y. X., Biasini, M., Beyermann, W. P. & Yin, Y. D. Superparamagnetic magnetite colloidal nanocrystal clusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 46, 4342–4345 (2007).

Liu, Y. G. et al. Development of crystal texture in Nd-lean amorphous Dd9Fe85B6 under hot deformation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 172502 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Basic Research Program of China (2010CB934601), the NSFC (51125001, 51172005, 90922033, 11274371), the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing (2122022) and the Doctoral Program (20120001110078).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H. and S.G. proposed the conceptual idea and participated in the analysis of results, discussing and writing the manuscript and provided financial support through grant application. Y.C. performed the synthesis and XRD experiments of samples. L.J. provided the synthetic method and X-ray Crystallography results. C.G. and S.W. characterized and analyzed the magnetic properties of samples. D.S. provided the MFM and AFM images of samples.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Info for publication

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, C., Jia, L., Wang, S. et al. Single Domain SmCo5@Co Exchange-coupled Magnets Prepared from Core/shell Sm[Co(CN)6]·4H2O@GO Particles: A Novel Chemical Approach. Sci Rep 3, 3542 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03542

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03542

This article is cited by

-

High coercivity SmCo5 synthesized with assistance of colloidal SiO2

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Morphology evolution of SmCox permanent magnetic nanoparticles

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2021)

-

Low remanence temperature coefficient Sm1−xErx(Co, Fe, Cu, Zr)z magnets operating up to 400 °C

Rare Metals (2020)

-

Chemical synthesis and coercivity enhancement of Nd2Fe14B nanostructures mediated by non-magnetic layer

Nano Research (2020)

-

Chemical synthesis of SmCo5/Co magnetic nanocomposites

Rare Metals (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.