Abstract

Morphology control of carbon-based nanomaterials (nanocarbons) is critical to practical applications because their physical and chemical properties are highly shape-dependent. The discovery of novel shaped nanocarbons stimulates new development in carbon science and technology. Based on direct reaction of CO2 with Mg metal, we achieved controlled synthesis of several different types of nanocarbons including mesoporous graphene, carbon nanotubes and hollow carbon nanoboxes. The last one, to our knowledge, has not been previously reported to this date. The method described here allows effective control of the shape and dimensions of nanocarbons through manipulation of reaction temperature. The formation mechanism of nanocarbons is proposed. As a proof of concept, the synthesized nanocarbons are used for electrodes in symmetrical supercapacitors, which exhibit high capacitance and good cycling stability. The reported protocols are instructive to production of nanocarbons with controlled shape and dimensions which are much desirable for many practical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carbon-based nanomaterials, such as fullerene, carbon fibers, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, nanodiamonds and hollow carbon nanostructures, known as nanocarbons, are important in many areas of modern science and technology including electronic nanodevices, energy storage, flat panel displays, drug delivery, biosensors, conductive coatings and environment remediation, etc1,2,3,4,5,6. The properties of nanocarbons are governed by a set of parameters including their size, morphology and structure. For example, when used in supercapacitors, CNTs play a key role to power advantage thanks to their low electronic and ionic charge-transfer resistances. The advantage of graphene is mainly due to high surface area and superior electrical conductivity; while carbide-derived carbon materials with uniform subnanometer pores led to a new insight in charge-storage mechanism of double-layer capacitance owing to desolvation effect in a confined system7,8,9,10,11. Hence, controlled synthesis of nanocarbons is the key to manipulating and tailoring their characteristics and broadens their applications. In general, the growth process of nanocarbons can be boiled down to the generation of carbon sources, the dominant aggregation state during carbonization, the conditions of processing and the key structural or textural features of the resulting products12. As a matter of fact, the production of nanocarbons largely depends on many factors like carbon precursors, substrate, catalyst, temperature, condensation and carbonization process, etc. Because of substantial differences in the production procedures, the flexibility and scope of change are highly sensitive to different methods and parameters. Thus, it still remains a challenge to assemble nanocarbons exhibiting controllable patterns at desired locations by a general method.

Although in recent years a considerable amount of interest has been dedicated to synthesis of nanocarbons, especially graphene and CNTs, all these preparation methods showed their disadvantages in one way or another. High cost is the biggest obstacle associated with chemical vapor deposition (CVD) process, which is by far the dominant method for high-volume production of CNTs and graphene. The price of bulk purified multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWNTs) is several times higher than the commercially available carbon fibers13. The production cost of graphene is high because its formation is related to interface growth mechanism and depends on the underlying substrates, such as Cu foil or Ni single crystal, that must be subsequently removed. Furthermore, the shape, size, purity and crystallographic orientation of nanocarbons need to be controlled for specific applications. Because of these difficulties, it is unlikely that graphene will become commercially available in the next decade13. The science and application of carbon nanotubes, ranging from surface chemistry to large-scale manufacturing are not yet fully understood14. On the other hand, we witnessed a great deal of success in preparing hollow carbon nanostructures by several methods including self-templating synthesis and template-free synthesis. However, most of these methods have disadvantages, such as multiple-step process and low throughput15. More importantly, high-quality hollow non-spherical carbon nanostructures are difficult to produce due to the extra difficulties involved including less controllable coating around high-curvature surfaces, the deficiency of dispersed anisotropic templates available and poor preservation of the shape with high residual stresses16. The pore structure of the end product has a tendency to maintain the spherical structure of initial template for meeting the need of the lowest surface Gibbs free energy17.

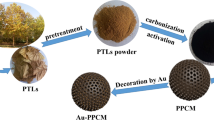

Here, we report synthesis of nanocarbons with controlled shape by direct reaction of CO2 with Mg metal. Our approach is based on different interfacial phase reaction mechanisms, including gas-solid (CO2 gas and Mg solid), gas-liquid (CO2 gas and Mg liquid) and liquid-gas-gas (Mg liquid, Mg gas and CO2 gas) interfaces. Combustion of Mg powders in CO2 atmosphere as rocket engine fuel for Mars missions had been explored18. Catalytic hydrogenation or chemical reduction of CO2 at supercritical state to organic molecules and carbon-based composites were also investigated and some significant progress had been made19,20. However, enclosed and high-pressure containers were required for ensuring supercritical state and the resulted materials with high impurity which consist of various morphologies. Alternatively, oxygen-deficient M ferrites (M = Ni, Mn, Zn, etc.) with a spinel structure had been intensively investigated for decomposition of CO2 into CO21. Conversion of CO2 into solid nanostructured carbon materials has also been reported22,23. To our knowledge, chemical reduction of CO2 into nanocarbons with controlled and substantial morphologies is not adequately investigated. Recently, we reported fabrication of ordered mesoporous nanographene using burn-quench method based on conversion of CO2 gas24. Our work demonstrated that the present method allows precise control and reproducible synthesis of nanocarbons with specific shape and dimensions through changing the reaction temperature to achieve controlled electrochemical capacitance. Sizable quantity, 0.3 g of mesoporous graphene (MPG), 0.8 g of carbon tubular nanostructures (CTN) and 1.0 g of hollow carbon nanoboxes (HCB), was yielded from 10 g of Mg powders. In addition, after dissolving Mg and MgO, the resulting Mg ions can be converted into Mg metal again and re-cycled for use in further synthesis of carbon nanostructures. We anticipate that direct chemical reduction of CO2 reported here can potentially lead to a scalable methodology for fabrication of large-area nanocarbons for many real world applications.

Results

Experimental verification in shape-controlled synthesis of nanocarbons

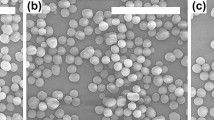

The dependence of morphology and microstructure of nanocarbons on reaction temperature is illustrated in Fig. 1. All the samples were obtained after 30 min reaction at aimed temperature and the reaction time was kept constant at 30 min unless otherwise stated. After 600°C reaction, block-shaped nanocarbons are formed (Fig. 1a). The block-shaped nanocarbons are composed of platelet-like carbon films (Fig. 1b). When the reaction temperature increases to 800°C, substrate-free fiber-shaped carbon nanostructures are obtained (Fig. 1c). The enlarged scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image shows that they are hollow fiber-like nanocarbons (Fig. 1d). With further increase in temperature up to 1000°C, cube-shaped structure of HCB is observed (Fig. 1e and 1f). Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) confirmed the nanocarbons are predominant form of carbon atoms accompanied by some oxygen and magnesium elements. The atomic percentages of carbon atoms are 97.8%, 99.0% and 90.1% for MPG, CTN and HCB, respectively (supplementary Figs. S1–S6 and Table S1). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis also indicates that main fit line represents graphite carbon (C-C), demonstrated by the strong peak at around 284.8 eV for nanocarbons in the C1s XPS spectra (supplementary Fig. S7)25. It is fascinating that several types of nanocarbon morphologies can be tailored by a simple control of reaction temperature without changing any other parameters like the volume ratio of gas, the mass of Mg powder, the reaction time and heating and cooling rates, etc.

Morphology and microstructure of nanocarbons.

(a) FESEM image of block-shaped MPG powders, (b) enlarged image of (a) shows the MPG consists of flake-like thin carbon films, (c) low magnification image of randomly oriented carbon tubular nanostructures, (d) high magnification image reveals hollow core and rough shell structure of CTN, (e) typical image of uniformity in particle size of carbon nanoboxes, (f) high magnification image illustrates cubic shape of HCB.

Detailed microstructure investigations using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were carried out on the nanocarbons. Typical TEM and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images of MPG are shown in Figs. 2a and 2b, respectively. Fig. 2a reveals that MPG exhibits sheet-like structure, but consists of randomly scrolled and crumpled sheets closely associated with each other. The latter arises from the wrinkles of graphene, which provide graphene-based materials with good mechanical properties and prevent further aggregation26,27. As can be seen in Fig. 2b, the presence of mesopores approximately 5–10 nm in size is evident in few-layers MPG. Also, we observed some single layer graphene with a thickness of 0.7 ± 0.6 nm by atomic force microscopy (AFM) (supplementary Fig. S8)28,29,30. Figs. 2c and 2d show a bunch of CTN and a single carbon tubular nanostructure, respectively. The size of shell structure is ≈25–30 nm and the internal diameter is ≈60 nm. However, unlike previous reported CNT with high crystallinity31,32,33, the present CTN are composed of many amorphous carbon nanosheets (supplementary Fig. S9).

TEM images of nanocarbons synthesized at different temperatures.

(a) sheet-like morphology of MPG in which scrolls and corrugations present, (b) high-resolution image of 5–10 nm diameter mesopore in the MPG, (c, d) low- and medium- magnification images of carbon tubular nanostructures, (e) low magnification image of HCB shows uniform particle size, hollow core microstructure and cubic shape, (f) medium-magnification image of HCB shows that the shell thickness and the side length of HCB are approximately as large as 80–100 and 230 ± 30 nm, respectively.

Novel hollow carbon nanoboxes (see Figs. 2e and 2f) are obtained when the reaction temperature further increases to 1000°C. Importantly, the carbon source was supplied by in-situ chemical reduction of CO2 and carbon atoms rearranged onto self-generated MgO template. The fabrication method described here can be used for large-scale manufacturing. The shell thickness of HCB is ca. 80–100 nm and the length of internal void is about 230 ± 30 nm. Note that the shell thickness could reach up to 100 nm, that is substantially higher than most reported hollow micro-/nanostructures, of which the value typically ranged from 5 to 20 nm, as well as those spherical counterparts and non-spherical shapes produced by templating synthesis or template-free synthesis34,35. Meanwhile, catalytic graphitization of carbons by metal oxides (MgO, Al2O3, SiO2, etc) can only produce a few graphene layers regardless of the reaction conditions, because the sheets meet each other during growth and then have to crease for overlapping an opposing graphene layer. The growth process becomes more difficult when the graphene layers become thicker. Eventually, only few-layers can be formed36. Moreover, the synthesis of hollow carbon with well-defined non-spherical shapes remained a significant challenge due to extra difficulties in forming a uniform coating around surface with large variation in curvature and poor preservation of the shape with high residual stresses17. It is reasonable that the growth of HCB in the present work probably can be attributed to a different mechanism, which will be discussed later.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the nanocarbons are shown in Fig. 3a. All three samples exhibit a relatively strong diffraction peak at 2θ = 24–26°, which is associated with the (002) diffraction line from hexagonal graphite (JCPDF No: #65-6212). Apparently, the intensity of (002) diffraction peak becomes stronger and shifts to higher 2θ angles from 23.88 to 26.51° with increasing reaction temperature. The corresponding d-spacings measured for MPG, CTN and HCB are 3.723, 3.419 and 3.359 Å, respectively. This finding suggests that the nanocarbons prepared at higher temperature have a tendency to form graphite structure whose interlayer spacing is 3.354 Å. The broad nature of the reflection indicates poor ordering of MPG sheets along the c-direction implying that the sample is not severely stack37. In addition, the XRD spectra show the CTN and HCB materials consist of amorphous carbon, which is probably due to the presence of not well crystalline grains of CTN and HCB. Further HRTEM characterization confirms that the walls of CTN and HCB are composed of short-range ordered carbon (supplementary Fig. S9 and Fig. S10). Note that sharp increment of diffraction intensity in the low-angle scatter results from high density of pores in the sample. The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) specific surface areas are 762, 1006 and 918 m2/g, respectively and the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) sorption cumulative volume of pores are 0.96, 1.06, 0.97 cm3/g for MPG, CTN and HCB. It demonstrates that the nanocarbons are mesopore rich, of which the BJH pore area between 1.7–300 nm is 486, 953 and 901 m2/g for MPG, CTN and HCB. The results of pore-size distribution calculated using a density functional theory (DFT) model, assuming a slit pore geometry of nanocarbons, indicate that the nanocarbons present well-defined micro- and mesopores (supplementary Fig. S11 and Table S2).

Raman spectra measured for MPG, CTN and HCB are illustrated in Figs. 3b–3d. Graphite-like carbon materials usually exhibit a Raman band at around 1580 cm−1 which is assigned to G-band and a peak at 1350 cm−1 assigned to D-band38. The G-band indicates original graphite features, whereas the D band is known to depend on disorder features of graphitic structures as well as the presence of small crystalline grains. We observed the positions of G-band peaks for MPG, CTN and HCB at 1588 ~ 1598 cm−1, corresponding to threefold-coordinated bonds in nanocarbons39,40. When compared to that of graphite, a frequency shift (~8–18 cm−1) toward higher wavenumber was found in nanocarbons because of their nano-scale crystallite sizes. The position of the D-band shifts to lower wavenumbers as it goes from MPG at 1353 cm−1 through CTN at 1347 cm−1 to HCB at 1343 cm−1. This decrease is associated with an increase in the amount of “organized” carbon in the samples, which is in agreement with above-discussed XRD results. The intensity of the D-band is inversely proportional to the effective crystallite size La in the direction of the graphite plane:

where ID and IG are the integrated intensities of the D and G bands, respectively41 and C(λL) is a wavelength dependent pre-factor and its value is 4.36 according to Matthews' work42. The average values of ID/IG are determined to be 1.36, 1.74 and 1.58 using the multi-peak fit (four Voigt functions for D, D′, D″ and G bands and the detailed fitting results are shown in the supplementary information, Figs. S12–14). The corresponding values of La calculated from equation (1) are 3.2 ± 0.4, 2.5 ± 0.1 and 2.8 ± 0.4 nm for MPG, CTN and HCB, respectively.

Electrochemical performance of supercapacitor with nanocarbon-based electrodes

These nanocarbons can potentially be used for energy generation and storage in supercapacitors, rechargeable batteries and hydrogen storage. Specifically, we assembled these nanocarbons as electrodes in supercapacitors with 6 M KOH aqueous electrolyte and measured their electrochemical properties. Data are shown in Fig. 4. We observed cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves that are nearly rectangular in shape, indicating good charge propagation within the electrodes, as shown in Fig. 4a. Apparently, the current density (J) of MPG is the largest, resulting in highest capacitance among these three kinds of nanocarbons. Fig. 4b illustrates the CV curves for MPG with the scan rate (ν) from 20 to 500 mV/s. (Data for CTN and HCB are shown in supplementary Fig. S15.) The nanocarbons-based supercapacitors showed ideal rectangular shape at high ν of 200 mV/s and the double-layer capacitance is maintained when ν is further increased to 500 mV/s, indicating excellent rate-capability in 6 M KOH. The internal resistances for these three materials used as supercapacitor electrodes are all lower than 1 Ω, as shown in Fig. 4c. Average specific capacitances (SC) calculated from the second to fifth charge-discharge (CD) processes are displayed in Fig. 4d. SC values of 150 F/g for MPG, 87 ± 3 F/g for CTN and 75 ± 2 F/g for HCB have been measured at J = 0.2 A/g. When J increased to 10 A/g, the SC decreased to 110 F/g for MPG, ≈70 F/g for CTN and ≈60 F/g for HCB, respectively. Fig. 4e gives typical CD curves at 0.2 A/g for nanocarbons-based symmetrical supercapacitors. The change in SC with respect to voltage remains linear at the high voltage. Although the presence of tiny amount of oxygen functionalized groups may contribute to pseudocapacitance, nearly rectangular shape of CV curves and the linear increase of current with increasing voltage indicate that the capacitance is primarily electrochemical double-layer capacitance in nature43,44. The pseudocapacitance based on faradaic reaction can reach 10–100 times higher than double layer capacitance but suffers a severe disadvantage of low cyclic lifetime45,46,47. Since the nanocarbon electrodes present electrochemical double layer capacitance, the SC shows no apparent deterioration after 10000 CD process at 5 A/g, as illustrated in Fig. 4f. The SC retentions for MPG, CTN and HCB are 95%, 97% and 98%, respectively. The inset of Fig. 4f is electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) data of nanocarbons supercapacitors that shows internal resistance of 0.4–0.7 Ω, slightly lower than that of supercapacitors before cyclic life-test.

Electrochemical performance of nanocarbons assembled as symmetrical supercapacitors in 6 M KOH.

(a) CV curves at 20 mV/s between 0–0.9 V, (b) CV curves of MPG at ν of 20, 60, 100, 200, 300 and 500 mV/s, (c) EIS curves. Inset shows the internal resistances of nanocabons are 0.5–1 Ω, (d) average SC of nanocarbons at galvanostatic CD current densities varied from 0.2 to 10 A/g, (e) typical galvanostatic CD curves of nanocarbons at a current density of 0.2 A/g, (f) SC retention versus cycle number for the symmetrical supercapacitor at a galvanostatic CD current density of 5 A/g and the inset is Nyquist plots of electrodes after cycling, the internal resistances of nanocabons decrease to 0.4–0.7 Ω.

For exploration of broad applications of supercapacitors, high energy density must be pursued. We used ionic liquid (IL) as electrolyte whose potential window is 3–4 times higher than that of aqueous electrolyte. Fig. 5a shows CV curves for nanocarbons-based symmetrical supercapacitors with 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate (EMIMBF4) as electrolyte. From the discharge portion of CD curves, average SC presented in Figs. 5b and 5c is 145 ± 3 F/g at 0.5 A/g for MPG (about 100 and 90 F/g for CTN and HCB, respectively). The values are 120, 75 and 60 F/g for MPG, CTN and HCB, respectively, when J increased to 2 A/g. The calculated energy density based on the active materials of supercapacitors for MPG reaches up to 80 Wh/kg at room temperature, which is comparable to curved graphene, activated graphene and high-purified single-wall carbon nanotube, where the reported values are 85, 70 and 94 Wh/kg, respectively48,49,50. Also, it is worth noting that the electrodes have high carbon loading of 4–5 mg/cm2, suggesting that with electrodes based on nanocarbons and produced on an industrial scale, energy storage devices with high electrochemical performances can be obtained. However, because of low electrical conductivity of IL electrolyte, the rate capability of nanocarbon electrodes is unsatisfactory (see Fig. 5b), as demonstrated by Nyquist plots shown in Fig. 5d. The internal resistances of 12 and 15 Ω were measured for MPG and CTN, respectively; while a value of >35 Ω was measured for HCB. Although all three kinds of nanocarbons illustrate similar equivalent series resistance (ESR) of 1–2 Ω, the diffuse resistance of HCB is several times higher than that of MPG and CTN; this is likely due to the fact that large ions of IL electrolyte are more difficult to penetrate into particulates of HCB. Thus, improving the conductivity, eliminating the impurities and adjusting pore structure will further enhance the electrochemical performances of the present nanocarbons. In addition, the electrochemical performances in tetraethylammonium tetrafluoroborate (TEABF4) in acetonitrile (AN) are aslo discussed. Detail data can be found in Fig. S16 of the supplementary informantion. Briefly, the SC are 90–65, 75–60 and 68–48 F/g for MPG, CTN and HCB, respectively, when J at CD process vary from 1 to 10 A/g. The SC maintains 92, 96 and 98% for MPG, CTN and HCB after 5 000 CD cycles at J of 10 A/g.

Electrochemical performance of nanocarbons assembled as symmetrical supercapacitors in EMIMBF4.

(a) CV curves at 40 mV/s between 0–4 V, (b) average SC of nanocarbons at various galvanostatic CD current densities, (c) typical galvanostatic CD curves of nanocarbons at a current density of 1 A/g, (d) Nyquist plots.

Discussion

We expect that the growth of nanocarbons by the present method may be divided into three different mechanisms, where each mechanism contains three major processes, as illustrated in Fig. 6. The initial stage is probably the same for all nanocarbons, at which carbon dioxide absorbs on the surface of metallic Mg and accepts electrons from Mg. Consequently, concurrent deoxygenation of carbon dioxide and growth of carbon skeleton occurred. However, the rearrangement of carbon bonds is different. Mg metal is solid at 600°C and transforms to liquid phase at 800 and 1000°C (the melting point and boiling points of Mg metal are 648.9 and 1090°C). When processed at 600°C, nucleation initiates from epitaxial growth on MgO and partially reacted Mg metal for MPG, as shown in Step A. While at 800°C, metal liquid drop assisted the nucleation process of CTN as shown in Step D. The reaction interface will become Mg liquid, partial Mg vapor and CO2 gas when the reaction temperature further increases to 1000°C, resulting in deposition process of MgO and carbon shown in Step G. Thus, it is conceivable that surface tension and surface energy are considerably altered at different conversion temperatures and thus lead to different interface reaction mechanisms.

Based on different nucleation process, the growth processes are controlled by planar epitaxial growth, metal liquid drop assisted growth and self-generation templating encapsulation growth, respectively, leading to planar, axial and point orientation for MPG, CTN and HCB. Carbon dioxide derived carbon precursors serve as soot that is made up of finite layers of carbon with the borders of the layers composed of carbon with “dangling bonds”, which are in the least thermodynamically stable form51. Graphene is two-dimensional sheet of carbon atoms with the honeycomb structure and hence possesses lower free energy than that of carbon precursors. The carbon atoms can easily be absorbed and get rearranged on the top surface of MgO to form graphene layer for minimization of free energy, in a way which is similar to CVD process (see Step B)52,53. Previous investigations on CTN and graphene catalytic growth on metal surface shed light on the importance of balancing the relationship between the decomposition of carbon-containing sources and the precipitation of the carbon54,55. It was concluded that the graphene or CNTs formation could not keep up with the carbon atom supply at the catalytic surface; this induced carbon island growth or encapsulation of the catalytic particles by a layer of carbon56. Although the overall synthetic process of MPG is conceptually very simple, a delicate interplay has been identified in the MPG precursor. When high CO2 gas flow of 300 sccm without Ar loading gas was used as working gas, the product was carbon block instead of MPG, which probably can be ascribed to the rapid condensation of carbon precusors (the morphology of carbon block was characterized by SEM, supplementary Fig. S17).

The CTN growth is likely surface tension or capillary-driven (see Step E). Like water movement in the capillary tube, the initial metal liquid droplets give rise to CTN formation. Moreover, the shape of CTN is dependent on the initial metal liquid droplets, which leads to a thicker shell of CTN than that produced by other growth mechanisms, such as, top carbon diffusion through catalytic particles, top carbon diffusion on catalytic particles, bottom carbon diffusion through catalytic particles and “catalyst free” synthesis route like nanochannels template-shaped pyrolytic carbon deposition57,58,59. An explanation for the CTN growth orientations based on chemical reduction of CO2 can be deduced on the basis of a work by Lou et al60. They observed conical CNTs growth under the reaction between supercritical CO2 and lithium liquid, where a continuous liquid lithium nanodroplets served as a root-growth method for the formation of CNTs along the axis of the nanotube from the root to the top.

On the other hand, the growth of HCB is linked to coating process, that is driven by different mass density of MgO and nanocarbons (3.58 g/cm3 for MgO and commonly lower than 2 g/cm3 for nanocarbons), coinciding with forming encapsulated structure. Previous studies demonstrated that the encapsulation of the catalysts by a layer of carbon would occur during the synthesis of CNT or carbon fibers when the decomposition rate of carbon-containing gases on the catalytic surface was faster than the precipitation rate of carbon in the form of CNT or carbon fibers61,62. Considering the cubic lattice of MgO, it is likely that the cubic MgO particle worked as a self-generated template that shaped the structure of HCB during growth (see Step H). To test this speculation, we took into account different reaction time varied from 5 to 360 min that would affect the coating process. The TEM images of the samples and the growth process of HCB were illustrated in the supplementary information (supplementary Fig. S18 and Schematic S1). It was interesting that the HCB displayed some near-spherical and pentagonal microstructures when the reaction time was as short as 5 min. As expected, the shell became thicker with prolonging reaction time from 30 to 120 min. The microstructure of HCB collapsed as the reaction time further increased to 360 min. The occurrence of near-spheroidal and pentagonal microstructure was related to the hexagonal lattice structure of Mg metal. The Mg metal would completely transformed into MgO at longer reaction time, consequently, the perfect hollow nanoboxes structure was formed and further carbon deposition led to thicker shell of HCB. The evolution of HCB structure and its change of shell structure supported the encapsulation process. We implied that the collapse of HCB could be ascribed to the activation by CO2 and the volume expansion of carbon growth. In short, the self-generated template MgO played a significant role in forming HCB structure.

The removal of MgO and remaining Mg results in purified MPG, CTN and HCB (see Step C, F, I). The possible formation mechanisms discussed here are based on the nucleation and growth process, however, the exact growth mechanism for converting CO2 into nanocarbons will be further understood when in-situ observation technique is successfully implemented.

In summary, starting from the same sources of Mg powder and CO2 gas, diverse carbon products, such as MPG, CTN and HCB, can be obtained at atmospheric pressure by manipulation of reaction temperature. The formation mechanisms of nanocarbons were discussed by analysis of their morphology and preferred orientations in combination with different phase interface reaction and self-generated template-guided growth mechanism. The yielded nanocarbons were used as electrodes for fabrication of symmetrical supercapacitors, which exhibited high capacitance, good cycling stability and high energy density value of 80 Wh/kg. Here, a remaining challenge would be to eliminate the defects of nanocarbons in terms of their ease of removal by the post process and to control the growth of nanocarbons with crystalline grains. We believe that the present approach will not be limited to the materials discussed here. With other precursors, this method can be extended to materials such as highly active metals to reduce oxygenic carbon sources or dehydrogenation process.

Methods

Synthesis of nanocarbons

The nanocarbons including MPG, CTN and HCB were synthesized by direct chemical reaction of Mg with CO2 gas. Before the reaction, a high-purity open ends Al2O3 tube (Φ 30 × 150 mm) filled with about 10 g Mg powders was put into a horizontal tube furnace (Φ 60 × 1200 mm, SGSL-1600X, Hefei Kejing Materials Technology CO., LTD, China) filled with argon gas. The furnace was heated to the desired temperatures (typically 600–1000°C) under a 100 sccm flowing Ar gas. For melting Mg metals, the temperature was maintained for 2 h at 800 and 1000°C. Then CO2 and Ar gas mixture of 4:1-1:4 volume ratios was flowing at 170–300 sccm. For comparison, single CO2 without loading Ar buffer gas was also discussed. Once expected reaction time was reached, CO2 gas flowing was turned off and Ar gas flowing was adjusted to 100 sccm again to ensure that the samples were cooled down to room temperature naturally under inert atmosphere. After the reaction, the products were soaked in 6 M HCl solution with 200 mL for 24 h, followed by washing and filtrating with deionized water to remove impurities. The carbon mass was then dried and subsequently examined for the structural, chemical and morphological characterization.

Characterization

Field-emission SEM was carried out on Zeiss Sigma scanning electron microscopes. EDS was carried out on a EDAX TEAM EDS. Samples for TEM analysis were prepared by drying a drop of nanocarbons dispersed in alcohol on ultrathin amorphous carbon-coated copper grids. TEM and HRTEM characterization was performed with a JEOL JSM-2100 operating at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. AFM images of MPG spin coated on a freshly cleaved mica surface were taken with a Nanoscope MultiMode SPM in tapping mode. Room-temperature Raman spectra were obtained with a RM2000 microscopic confocal Raman spectrometer employing a 514 nm laser beam. XRD of nanocarbons was performed with a MAC M18XHF diffractometer with Cu radiation between 5 and 70° with a scan rate of 8°/min. XPS analysis was measured with a PHI Quantear SXM (ULVAC-PHINC). Surface area measurements of dried nanocarbons were carried out with Micromeritics TriStar II 3020 surface area and pore size analyzer using nitrogen gas adsorption-desorption isotherm at −196°C. BET surface area was calculated from the adsorbed amount of N2 at the relative pressure of P/P0 below 0.3 and pore size distribution pore-size distribution calculated by using a slit DFT model.

Electrochemical measurements

90 wt% of the nanocarbons and 10 wt% Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) binder were mixed in isopropyl alcohol and blended for 30 min before using. The obtained slurry was then rolled and coated onto stainless steel meshes and then dried in vacuum at 120°C for 24 h to remove the solvent to form the working electrode. After drying, the electrodes were pressed under manual compression testing machine at 40 MPa. Symmetrical supercapacitors were fabricated by sandwiching a polypropylene separator between two eletrodes with thickness of 40–70 μm for each. The load mass ranged from 4–5 mg/cm2 for a single electrode. 6 M KOH aqueous solution, TEABF4 in 1 M AN and ionic liquid (EMIMBF4) were used as the electrolytes. 2032 type coin cells with organic and ionic liquid electrolytes were assembled in a dry glovebox (Labstar, Mbraun, Germany) in Ar with less than 1 ppm oxygen and H2O.

CV curves and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were carried out using AutoLab PGSTAT302N equipment. CV curves were scanned at voltage ramp rates from 20 to 500 mV/s. EIS was obtained in the frequency range from 100 kHz to 10 mHz with a ±10-mV voltage amplitude at open circuit voltage. Galvanostatic CD process and cycle-life test of supercapacitors was measured on an Arbin MSTAT4 multi-channel galvanostat/potentiostat instrument. Average SC of single electrode was calculated from the second to fifth galvanostatic CD processes using the following equation:

Where I, Δt, U and M are the applied current, the discharge time, the voltage window and the total mass of both electrodes, respectively.

The effective power density (P) and energy density (E) were calculated by using the following equations:

All of the values including the current densities were normalized with respect to the combined weight of both electrodes.

References

Futaba, D. N. et al. Shape-engineerable and highly densely packed single-walled carbon nanotubes and their application as super-capacitor electrodes. Nat. Mater. 5, 987–994 (2006).

Wang, D. W., Li, F., Liu, M., Lu, G. Q. & Cheng, H. M. 3D aperiodic hierarchical porous graphitic carbon material for high-rate electrochemical capacitive energy storage. Angew. Chem. 120, 379–382 (2008).

Sharma, P. et al. Enhancing electrochemical detection on graphene oxide-CNT nanostructured electrodes using magneto-nanobioprobes. Sci. Rep. 2, 1–7 (2012).

Kimura, H., Futaba, D. N., Yumura, M. & Hata, K. Mutual exclusivity in the synthesis of high crystallinity and high yield single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 9219–9224 (2012).

Mochalin Vadym, N., Shenderova, O., Ho, D. & Gogotsi, Y. The properties and applications of nanodiamonds. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 11–23 (2011).

Sun, J. et al. Carbon nanorings and their enhanced lithium storage properties. Adv. Mater. 25, 1125–1130 (2013).

Zhang, L. L. & Zhao, X. Carbon-based materials as supercapacitor electrodes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 2520–2531 (2009).

Zhang, L. et al. Porous 3D graphene-based bulk materials with exceptional high surface area and excellent conductivity for supercapacitors. Sci. Rep. 3, 1408; 10.1038/srep01408 (2013).

Chmiola, J. et al. Anomalous increase in carbon capacitance at pore sizes less than 1 nanometer. Science 313, 1760–1763 (2006).

Chmiola, J., Largeot, C., Taberna, P. L., Simon, P. & Gogotsi, Y. Desolvation of ions in subnanometer pores and its effect on capacitance and double-layer theory. Angew. Chem. 120, 3440–3443 (2008).

Largeot, C. et al. Relation between the ion size and pore size for an electric double-layer capacitor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 2730–2731 (2008).

Inagaki, M. & Radovic, L. R. Nanocarbons. Carbon 40, 2263–2284 (2002).

De Volder, M. F., Tawfick, S. H., Baughman, R. H. & Hart, A. J. Carbon nanotubes: present and future commercial applications. Science 339, 535–539 (2013).

Zhang, Q., Wang, W., Goebl, J. & Yin, Y. Self-templated synthesis of hollow nanostructures. Nano Today 4, 494–507 (2009).

Terrones, M. Science and technology of the twenty-first century: synthesis, properties and applications of carbon nanotubes. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 33, 419–501 (2003).

Wang, Z. & Lou, X. W. D. TiO2 Nanocages: Fast Synthesis, Interior Functionalization and Improved Lithium Storage Properties. Adv. Mater. 24, 4124–4129 (2012).

Lou, X. W. D., Archer, L. A. & Yang, Z. Hollow micro-/nanostructures: synthesis and applications. Adv. Mater. 20, 3987–4019 (2008).

Shafirovich, E. Y. & Goldshleger, U. Combustion of magnesium particles in CO2/CO mixtures. Combust. Sci. Technol. 84, 33–43 (1992).

Kumar, B. et al. Photochemical and photoelectrochemical reduction of CO2 . Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 63, 541–569 (2012).

Jessop, P. G., Ikariya, T. & Noyori, R. Homogeneous catalytic hydrogenation of supercritical carbon dioxide. Nature 368, 231–233 (1994).

Tabata, M. et al. CO2 decomposition with oxygen-deficient Mn (II) ferrite. J. Mater. Sci. 28, 971–974 (1993).

Zhang, C.-L., Li, S., Wang, L.-J., Wu, T.-H. & Peng, S.-Y. Studies on the decomposing carbon dioxide into carbon with oxygen-deficient magnetite: II. The effects of properties of magnetite on activity of decomposition CO2 and mechanism of the reaction. Mater. Chem. Phys. 62, 52–61 (2000).

Wang, J.-F., Wang, K.-X., Wang, J.-Q., Li, L. & Chen, J.-S. Decomposition of CO2 to carbon and oxygen under mild conditions over a zinc-modified zeolite. Chem. Commun. 48, 2325–2327 (2012).

Zhang, H. et al. Large-scale production of nanographene sheets with a controlled mesoporous architecture as high-performance electrochemical electrode materials. ChemSusChem, 6, 1084–1090 (2013).

Gao, W., Alemany, L. B., Ci, L. & Ajayan, P. M. New insights into the structure and reduction of graphite oxide. Nat. Chem. 1, 403–408 (2009).

Meyer, J. C. et al. The structure of suspended graphene sheets. Nature 446, 60–63 (2007).

Geringer, V. et al. Intrinsic and extrinsic corrugation of monolayer graphene deposited on SiO2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 076102 (2009).

Lui, C. H., Liu, L., Mak, K. F., Flynn, G. W. & Heinz, T. F. Ultraflat graphene. Nature 462, 339–341 (2009).

Reina, A. et al. Large area, few-layer graphene films on arbitrary substrates by chemical vapor deposition. Nano Lett. 9, 30–35 (2008).

Fan, Z.-J. et al. Facile synthesis of graphene nanosheets via Fe reduction of exfoliated graphite oxide. ACS nano 5, 191–198 (2010).

Hofmann, S., Ducati, C., Robertson, J. & Kleinsorge, B. Low-temperature growth of carbon nanotubes by plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 135–137 (2003).

Hofmann, S. et al. In situ observations of catalyst dynamics during surface-bound carbon nanotube nucleation. Nano Lett. 7, 602–608 (2007).

Chen, T. et al. Intertwined aligned carbon nanotube fiber based dye-sensitized solar cells. Nano Lett. 12, 2568–2572 (2012).

Hu, J., Chen, M., Fang, X. & Wu, L. Fabrication and application of inorganic hollow spheres. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 5472–5491 (2011).

Deshmukh, A. A., Mhlanga, S. D. & Coville, N. J. Carbon spheres. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. R 70, 1–28 (2010).

Rümmeli, M. et al. On the graphitization nature of oxides for the formation of carbon nanostructures. Chem. Mater. 19, 4105–4107 (2007).

Yadav, P. et al. A 3D hexaporous carbon assembled from single-layer graphene as high performance supercapacitor. ChemSusChem 5, 2159–2164 (2012).

Ferrari, A. et al. Raman spectrum of graphene and graphene layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 187401 (2006).

Dillon, R., Woollam, J. A. & Katkanant, V. Use of Raman scattering to investigate disorder and crystallite formation in as-deposited and annealed carbon films. Phys. Rev. B 29, 3482 (1984).

Robertson, J. Amorphous carbon. Adv. Phys. 35, 317–374 (1986).

Knight, D. S. & White, W. B. Characterization of diamond films by Raman spectroscopy. J. Mater. Res. 4, 385–393 (1989).

Matthews, M., Pimenta, M., Dresselhaus, G., Dresselhaus, M. & Endo, M. Origin of dispersive effects of the Raman D band in carbon materials. Phys. Rev. B 59, R6585–6588 (1999).

Stoller, M. D., Park, S., Zhu, Y., An, J. & Ruoff, R. S. Graphene-based ultracapacitors. Nano Lett. 8, 3498–3502 (2008).

Yuan, W. et al. The edge-and basal-plane-specific electrochemistry of a single-layer graphene sheet. Sci. Rep. 3, 2248; 10.1038/srep02248 (2013).

Conway, B., Birss, V. & Wojtowicz, J. The role and utilization of pseudocapacitance for energy storage by supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 66, 1–14 (1997).

Simon, P. & Gogotsi, Y. Materials for electrochemical capacitors. Nat. Mater. 7, 845–854 (2008).

Zhang, H. et al. One-step electrophoretic deposition of reduced graphene oxide and Ni(OH)2 composite films for controlled syntheses supercapacitor electrodes. J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 1616–1627 (2013).

Liu, C., Yu, Z., Neff, D., Zhamu, A. & Jang, B. Z. Graphene-based supercapacitor with an ultrahigh energy density. Nano Lett. 10, 4863–4868 (2010).

Zhu, Y. et al. Carbon-based supercapacitors produced by activation of graphene. Science 332, 1537–1541 (2011).

Hiraoka, T. et al. Compact and light supercapacitor electrodes from a surface-only solid by opened carbon nanotubes with 2 200 m2 g−1 surface area. Adv. Funct. Mater. 20, 422–428 (2010).

Smalley, R. Self-assembly of the fullerenes. Accounts Chem. Res. 25, 98–105 (1992).

Yuan, Q. et al. Magic carbon clusters in the chemical vapor deposition growth of graphene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 2970–2975 (2011).

Zhang, W., Wu, P., Li, Z. & Yang, J. First-principles thermodynamics of graphene growth on Cu surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 17782–17787 (2011).

Delhaes, P. Chemical vapor deposition and infiltration processes of carbon materials. Carbon 40, 641–657 (2002).

Loginova, E., Bartelt, N., Feibelman, P. & McCarty, K. Factors influencing graphene growth on metal surfaces. New J. Phys. 11, 063046 (2009).

Toebes, M. L., Bitter, J. H., Van Dillen, A. J. & de Jong, K. P. Impact of the structure and reactivity of nickel particles on the catalytic growth of carbon nanofibers. Catal. Today 76, 33–42 (2002).

Gamaly, E. G. & Ebbesen, T. W. Mechanism of carbon nanotube formation in the arc discharge. Phy. Rev. B 52, 2083–2089 (1995).

Kusunoki, M., Suzuki, T., Hirayama, T., Shibata, N. & Kaneko, K. A formation mechanism of carbon nanotube films on SiC (0001). Appl. Phys. Lett. 77, 531–533 (2000).

Xu, W., Kyotani, T., Pradhan, B. K., Nakajima, T. & Tomita, A. Synthesis of aligned carbon nanotubes with double coaxial structure of nitrogen-doped and undoped multiwalls. Adv. Mater. 15, 1087–1090 (2003).

Lou, Z., Chen, C. & Chen, Q. Growth of conical carbon nanotubes by chemical reduction of MgCO3 . J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 10557–10560 (2005).

Nikolaev, P. et al. Gas-phase catalytic growth of single-walled carbon nanotubes from carbon monoxide. Chem. Phys. Lett. 313, 91–97 (1999).

Bower, C., Zhou, O., Zhu, W., Werder, D. & Jin, S. Nucleation and growth of carbon nanotubes by microwave plasma chemical vapor deposition. Appl. Phy. Lett. 77, 2767–2769 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge suggestions and discussions with Dr. B. Ma at ANL. This work was supported by the “Knowledge Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences” under project no. KJCX2-YW-W26, the “Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission” under project no. Z111100056011007 and the “National Natural Science Foundation of China” under project nos. 21001103 and 51025726.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.T.Z. and Y.W.M. proposed and designed the project, H.T.Z. and X.Z. performed the experiments, H.T.Z. and X.Z.S. performed characterizations, H.T.Z. and Y.W.M. analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. All the authors participated in discussions of the research.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

supporting information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Zhang, X., Sun, X. et al. Shape-controlled synthesis of nanocarbons through direct conversion of carbon dioxide. Sci Rep 3, 3534 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03534

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03534

This article is cited by

-

Sustainable synthesis of multifunctional nanomaterials from rice wastes: a comprehensive review

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Carbon quantum dot induced hemolysis and anti-angiogenesis in proliferating cancers with Vitis vinifera as the source material

Vegetos (2022)

-

The Role of Temperature on Physical–Chemical Properties of Green Synthesized Porous Carbon Nanoparticles

Waste and Biomass Valorization (2020)

-

3D Hierarchical Porous Graphene-Based Energy Materials: Synthesis, Functionalization, and Application in Energy Storage and Conversion

Electrochemical Energy Reviews (2019)

-

Modelling of X-ray patterns using Fourier transforms: application to nanomaterials

Indian Journal of Physics (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.