Abstract

An important aspect of chemical reactions involves understanding the intermediate steps from reactants to products. The iterative use of mass spectrometry and X-Ray crystallography is demonstrated to be a powerful combination in this respect. We have applied them in identifying molecular clusters in solution followed by their solid-state structural characterizations. We used a key ligand, 2-[(2-hydroxy-3-methoxy-benzylidene)-amino]-ethanesulfonate (L), which serves as chelating/bridging units to stabilize the precursor [Li4Ni6(OH)2(L)6(CH3CN)6](ClO4)2·4CH3CN. The results of subsequent reactions witness a cascade of processes involving fragmentation, inner bridging ligand substitution (OH− to OCH3−), changing modes of binding (chelate to monodentate) of the key ligand, ion-trapping and exchange (Li+, Na+ and Ca2+) and their site preferences, coordinating and non-coordinating solvents (CH3CN to CH3OH, H2O and EtOH) replacement. The flexibility of the Ni3OL3 species in solution permits the formation of six derivatives. The complimentary techniques open a broader prospect for cluster design and applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Among the primary goals in chemistry is to understand the way reactions progress and how different bonding interactions control the products1,2,3. Recently several transformations following initial formation of a precursor solid, for example ligands or metals exchange within crystals in solution without altering the structure and crystallinity have been recognized4,5. The stability and flexibility of Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) make them versatile systems for such study6,7. For example, two typical transformations in MOFs are single-crystal to single-crystal (SC-SC)8,9,10 and Post Synthetic Modification (PSM) to incorporate specific reactivity and functionality11,12. Apart from MOFs, an appealing chemistry is to focus on second stage reactions of metal coordination clusters in solution without destroying the molecular structures to create new derivatives (Supplementary Table S1)13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. In fact, metal coordination clusters responsive to different stimuli in solution generating novel crystalline derivatives is an effective strategy for cluster design and applications.

However, when such reactions involve big molecules such as supramolecular cages21,22 and high nuclearity coordination clusters23,24,25, it is often difficult to follow the changes due to the complicated dynamics involving bond breaking and reforming in solution. Techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy can provide information that allows one to follow certain events and propose a mechanism26. When it comes to proposing a process involving the transformations of metal coordination clusters via their multi-components rearrangements in solution, it has been difficult to do so using such technique27,28. Electrospray Ionisation Mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) is an alternative technique to study such transformation17,18,29,30,31,32. In particular, ESI-MS is very useful when the metals are paramagnetic, rendering NMR difficult33,34. In this work, we describe the chemistry of a flexible cluster in solution using ESI-MS and single-crystal X-ray diffraction(SCXRD) iteratively to follow the reactions towards ion-trapping and the rearrangements of the ligands, the incorporated solvents and the central inorganic core. The “key” ligand, 2-[(2-hydroxy-3-methoxy-benzylidene)-amino]-ethanesulfonate35, serves as chelating/bridging units to stabilize Ni2+ and Li+ ions into a novel cluster precursor [Li4Ni6(OH)2(L)6(CH3CN)6](ClO4)2·4CH3CN (1, Fig. 1) for subsequent reactions with incorporation of Na+ or Ca2+ and other bridging ligand and solvents. Furthermore, magnetization measurement was used to monitor the effect of these changes leading to a change from ferromagnetic to antiferromagnetic exchange interaction depending on the bridging OH− or OCH3−.

The six components of 1 that are observed to be either exchangeable or sustained rearrangements.

(For the four coordination modes of the ligand see Supplementary Fig. S1).

Results and Discussion

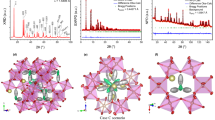

Following solvothermal reaction of Ni2+ with the ligand Li2L in CH3CN green crystals of the heterometallic compound [Li4Ni6(OH)2(L)6(CH3CN)6]·(ClO4)2·4CH3CN (1) was isolated. It is found to be a dimerized form of a bimetallic cubane (Fig. 2)36. The central part of each cube [LiNi3] is a trimer of edge-sharing octahedral nickel with a μ3-OH− bridge that is chelated by the N(imine)-O(hydroxy) of three ligands on its periphery. The O(hydroxy)-O(methoxy) form a distorted trigonal prism cage where the lithium resides while one O(sulfonate) is involved in coordination to a nickel atom and then two cubanes are bridged by a Li(μ2-O)2Li unit through oxygen atoms of the sulfonate. Although the bimetallic cube [LiNi3] appears similar to the K+ and Na+ analogues, with the alkali metal in a slightly distorted triangular prism by the oxygen atoms of the phenoxo and methoxy, there are some major differences in the orientation of the ligands due to the bonding of the sulfonate in 1 as well as to the geometric parameters associated with the difference in ionic radii of the alkali metals. The three L2− with two unusual hexadentate modes (LA: μ5:η1:η3:η1:η1:η2:η1; LB: μ4:η1:η3:η1:η1:η1, Supplementary Fig. S1) are arranged around the [Ni3(μ3-OH)] core in a propeller-like form to generate a pseudo-C3-symmetry.

The first question that arises concerns “which one of the two locations of the lithium atom (inner or outer-cubic Li+) in 1 will be thermodynamically more stable?” Thus, we performed a comparative synthesis using the same concentrations of starting reagents from CH3CN at ambient condition. [LiNi3(OH)(L)3(CH3CN)3]·CH3CN (2) was the only product. It consists of a cubane structure with the Li+ in the trigonal prism site on the one side of the metal-organic [Ni3(μ3-OH)] waist and the hydroxide pointing in the opposite direction (Fig. 2). 2 is isostructural to the reported bimetallic cubane with [Ni3O] trimer and Na+ or K+36.The ambient temperature and pressure synthesis indicates the lithium may have a preference for the trigonal prism site in the cuboidal [LiNi3].

The ESI-MS spectra of 1 and 2 in methanol indicate that the [LiNi3(OH/OCH3)(L)3] units is more stable in solution than its dimerized [Li4Ni6] form (see later). We therefore isolated the tetranuclear cluster by recrystallizing crystals of 1 from methanol at room temperature. The new compound has a different morphology and the SCXRD reveals a different structure with the formula [LiNi3(OCH3)(L)3(CH3OH)4]·2CH3OH·H2O (3, Fig. 2). Firstly, the structure is not cubane and the lithium atom adopts a tetrahedral geometry with three sulfonate oxygen atoms and a terminal methanol. Secondly, μ3-OCH3− inner bridge has replaced μ3-OH− but it is located on the opposite side of the trimer. Thirdly, the terminal coordinated CH3CN is replaced by CH3OH. The deformation of the metal-core introduces severe strain on the three μ3-phenolato oxygen atoms of the L2− in 1 and forces them from bridging mode to simple monodentate in 3, while the ethylene-sulfonate groups have changed from terminal chelating to μ2-bridging two Ni atoms. The three L2− adopt the LD: μ3:η1:η1:η2:η1 mode. These changes cause drastic rearrangement of the ligands around the fairly rigid Ni3O core while retaining the same coordination bonds. The structure of 3 is very different to that of 2, where the alkali metal ions are in the pseudo triangular prism cage. From this observation one may infer that the Li+ is more stable in a tetrahedral than the trigonal prism, contrary to what we inferred above. However, an explanation of this difference in site preference may come from the consideration of which site is more easily solvated. The results indicate it is the Li(O2)Li dimeric unit. As the bridge between the two Li+ is broken through solvation with methanol, the Li+ adopts a tetrahedral coordination and the three sulfonate groups become equivalent. Consequently, the methoxy groups are forced apart so that the other Li+ is freed from the trigonal prism site while the ligands are rearranged by tilting and rocking around the [Ni3] moiety. Furthermore, the methanolate being on the opposite side of the hydroxide obstructs the Li+ of cuboidal [LiNi3] from settling in that position.

It was clear from the aforementioned transformation of 1 to 3 that the structural rearrangements occurred mainly in the cuboidal [LiNi3] unit. Like in 1, 2 also possesses the [LiNi3] unit, thus similar structure rearrangements should be possible. To prove this hypothesis, we dissolved 2 in CH3OH and obtained [LiNi3(OH)(L)3(H2O)3]·CH3OH·3H2O (4). Contrary to what was expected, SCXRD data of 4 reveal the structure is similar to 2. Only H2O has replaced the coordinated CH3CN while CH3OH and H2O are the solvent molecules. Although this conformation is retained for 2 in methanol, it is different to the rearrangements taking place for 1. We can tentatively suggest that Li+ coordinated by the three sulfonate groups like a joint serves as an indispensable part in the dynamics of the rearrangement process of 1.

Subsequently we explored the effect of solvent on the precursor cluster32. After the ESI-MS spectra of 1 dissolved in EtOH confirming the presence of the heterometallic [LiNi3(L)3]+ species, ethanol was employed in place of methanol for recrystallizing 1. The SCXRD reveals the crystal is [LiNi3(OH)(L)3(H2O)3]·EtOH·3H2O (5) and its structure is different from that of 3. It is the half of 1 without the central Li(O)2Li moiety, further supporting the Li(O2)Li site is more easily solvated. It is therefore the Li+ equivalent of 2 and 4. The OH− is in the same position as in 1 and the Li+ is in the trigonal prism site. L2− adopts the LC: μ4:η1:η3:η1:η1:η1 coordination mode.

In the ESI-MS of only one crystal of 3 dissolved in methanol (see later), we noticed that ion exchange (Li+ to Na+) could happen within the [Ni3(OCH3)(L)3]− unit even in presence of trace amount of Na+. We therefore dissolve crystals of 1 and NaCl in methanol for recrystallization and obtained needle shaped crystals of [NaNi3(OCH3)(L)3(CH3OH)4]·2(CH3OH)·(H2O) (6) after a few days. The SCXRD reveals a structure similar to that of 3 with μ3-OCH3− and Na+ in a tetrahedral coordination of the three sulfonate oxygen atoms and one methanol (Fig. 3).

By changing monovalent alkali to divalent alkaline earth metal ions, structural variants are expected. Using CaCl2 instead of NaCl [CaNi6(OCH3)2(L)6(CH3OH)2(H2O)4]·2(CH3OH)·6(H2O) (7) was obtained (Fig. 3). SCXRD reveals the Ca2+ sits in an octahedral site built by the ethylene-sulfonate groups of two [Ni3(OCH3)L3]− units to give a neutral molecule. The rearrangement of the ligands around the [Ni3(OCH3)L3]− forces the methoxy groups apart to be able to accommodate any potential guest cation. Thus, the ionic radius of 1.00 Å for Ca2+, being similar to that of Na+, seems to be the driving force, although the soft sulfonate tendency towards the hard cation may enhance this preference in site. The one notable difference in the structure is two of the axial CH3OH are replaced by H2O, presumably from the wet CaCl2. The L2− ligands adopt the LD: μ3:η1:η1:η2:η1 mode.

In order to understand the parameters that may affect the structural transformations, we have performed a comprehensive crystallographic survey of compounds of this family. The uniqueness of these molecules is the presence of the central NiII3O core, which is a fragment of the Brucite Mg(OH)2 structure. It consists of three edge-sharing octahedra with one common μ3-O. The Ni···Ni distances lie between 3.098–3.222 Å and the Ni-O-Ni angles from 95.48 to 104.37°. The μ3-O bridge is either OH− or OCH3−, but can equally be OEt− as indicated by the ESI-MS data (see later). When recrystallization of 1 from methanol is performed the OH− is replaced by OCH3−. If one starts from 2, which has the Li+ of cuboidal [LiNi3] unit in the trigonal prism cage, then no replacement takes place. This evidences that the Li(O2)Li bridge in 1 is easier to solvate than the Li+ in the trigonal prism site. The exchange of OH− by OCH3− is therefore accompanied with a flip of the octahedra and drastically rearranges the ligands. The ligands chelate in a propeller fashion, thus introducing chirality to each molecule but the presence of both Δ and Λ enantiomers in the crystals make them achiral.

The Ni3O core with a μ3-O bridge, the organic ligand, the trapped ion and the coordinated solvents represent the four principal components forming the molecule (Fig. 4). There are few common features, i.e. the organic ligand chelates the Ni3O moiety through the N(imine)-O(hydroxy) and one O(sulfonate) in terminal or bridging mode, while leaving the other two O(sulfonate) and O(methoxy) free for further bonding interactions. The major difference for the seven compounds is that the μ3-OH− exclusively points upward towards the sulfonate and μ3-OCH3− downward towards the methoxy. Thus, for those with μ3-OH− the Li+ prefers the trigonal prism site formed by the O (hydroxy) and O (methoxy) below the mineral waist (e.g. as for 1, 2, 4 and 5) while for those with μ3-OCH3− the Li+ (3), Na+ (6) or Ca2+ (7) are held by the O(sulfonate) in tetrahedral (Li+ and Na+) or octahedral (Ca2+) coordination. A flip of the Ni3O unit, equivalent to an inversion to the inorganic moiety, is observed when OCH3− replaces OH−. It happens without change in the polarity of the ligands, that is the sulfonate is still pointing upward and the methoxy downward. To retain the octahedral Ni coordination accompanying the flip (OH− to OCH3−), the O(sulfonate) changes from monodentate to μ2-bridging and concertedly the O(hydroxy) from μ3-bridging two Ni2+ and one Li+ to monodentate to one Ni2+. The rearrangement that followed reveals both pivoting and rocking of the ligands about the Ni3O core.

Two of the major structural changes exemplified by the reactions of 1 to 3 or 5.

The visual surface highlights the multiple bonding rearrangements defined by the six parameters of Supplementary Table S2.

The polydentate Schiff-base ligand has an interesting laboratory of binding sites where all the coordinating atoms are placed on one side of the molecule segregating the clusters on formation33,34,36. The N(imine)-O(hydroxy) and a O(hydroxy)-O(methoxy) can only chelate while the sulfonate has chelating, bridging as well as terminal coordination functionalities. The sulfonate has two modes of coordination depending on the μ3-O bridge; for μ3-OH− it adopts monodentate coordination and for μ3-OCH3− it bridges two Ni2+. The O(sulfonate) can be as close as 3.18 Å (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S2), for the μ3-OCH3− bridged compounds, to provide three bonds to stabilize Li+ (3), Na+ (6) and Ca2+ (7). These M′-O(sulfonate) distances are 1.94 (Li+, 3), 2.21 (Na+, 6) and 2.33 Å (Ca2+, 7). For the μ3-OH− bridge compounds, the O···O(sulfonate) distances are far apart (>5 Å) to be involved in coordination. However, for 1 it is ca. 3.13 Å and is bonded to the Li(μ2-O2)Li bridging unit.

The methoxy groups are important in contributing to the formation of a pseudo trigonal prism cage in the form of a three-fingered claw to accommodate the Li+ and Na+ but not the Ca2+. In all the compounds with μ3-OH− bridges the alkali metals are located in this pseudo trigonal prism cage. The average Li-O(hydroxo) is 2.04 Å while the Li-O(CH3) ranges from 2.18 to 2.29 Å. As the ionic radii increases from Li+ (0.76 Å) to Na+ (1.02 Å), the M′-O (hydroxo) bond distance get longer accordingly, but the M′-O (CH3) increases less. With an ionic radius of 1.00 Å for Ca2+ it should in principle be accommodated in this cage but this is not the case.

The alkali and alkaline earth metals can be trapped at two sites, the trigonal prism of the O(hydroxy)-O(methoxy) and the three O(sulfonate), available for coordination. Although both are energetically favorable, the sulfonate may be the softer. However, the deciding condition for one or the other is the μ3-O bridge. When OCH3− is present the trigonal prism site is occupied and only the sulfonate is available. Thus three bonds are contributed by each single-cluster to the tetrahedral Li+ (3) and Na+ (6), while an octahedral site is found for the Ca2+ (7) by two clusters.

The coordinated solvents serve primarily to complete the octahedral coordination sphere of the nickel atoms but are sites potential for further chemistry. They appear to be labile and at ease to exchange between CH3CN, CH3OH and H2O but not ethanol. The weak interactions between neighboring molecules in the seven structures are shown in Supplementary Fig. S2.

The ESI-MS performed on a methanol solution of selected few crystals of 1 shows the highest intensity peaks were those belonging to [LiNi3(L)3]+ at 954.04 (calc.: 953.92), [Ni3(OH)(L)3]− at 963.99 (963.91) and [Ni3(OCH3)(L)3]− at 978.01 (977.93) where the OH− has been replaced by OCH3−, suggesting that the [LiNi3(OH/OCH3)(L)3] molecular units is more stable in solution than its dimerized form [Li4Ni6(OH/OCH3)2(L)6] observed in the solid (Figure 5(a), (b) and its corresponding calculated fit Supplementary Fig. S3(a), (b)) in agreement with the structure reported for 2. The latter three species were the principal peaks in the spectrum of 2 in methanol (Supplementary Fig. S4). The [LiNi3L3] fragment was also found to be the dominant species in the MS of crystals of 1 dissolved in water indicating the high stability even in the very polar aqueous medium (Supplementary Fig. S5). The data also indicate the exchange of the terminal CH3CN for CH3OH and H2O and the μ3-OH− being replaced by μ3-OCH3−. These changes were confirmed by the crystallography of 3.

The ESI-MS study of multi-components rearrangements of 1.

The ESI-MS spectra and analyses of 1 in methanol (top: (a) positive-ion mode, (b) negative-ion mode), of 3 in methanol (middle: (c) positive-ion mode, (d) negative-ion mode) and of 1 and NaCl in methanol (bottom): (e): positive-ion mode; (f): negative-ion mode).

After observing the difference of solubility for 1 in methanol and ethanol, the solution state of 1 in ethanol was studied (Supplementary Fig. S6, S7). The ESI-MS spectra from few crystals of 1 dissolved in EtOH reveal the dominant positive ion peak to be [LiNi3(L)3]+ at 953.95 (953.92) confirming the presence of the heterometallic cluster. The negative mode dominant peaks correspond to the species [Ni3(OH)(L)3(CH3CN)2]− at m/z 1045.89 (1045.96) and its inner bridge replaced [Ni3(OCH2CH3)(L)3]− at 991.97 (991.94) with almost equal intensity, which suggest that CH2CH3O− may effectively replace OH− as CH3O− during the ESI-MS process32. These observations increased our desire to understand whether the recrystallization result of 1 from ethanol will be rearrangement accompanied by inner bridge replace (OH− by CH2CH3O−) or not. The crystal structure of shows that 5 is a neutral half of 1, [LiNi3(L)3(OH)] cluster and the OH− is not exchanged.

The ESI-MS of only one crystal of 3 dissolved in 1 mL of methanol shows new sets of peaks which can only be assigned to fragments containing Na+, such as [Ni3(L)3 + Na+]+ at m/z 969.91 (969.90) (Fig. 5(c), (d) and Supplementary Fig. S3(c), (d)). This unexpected observation turned out to be a contamination to the instrument from the sodium formate used for calibration. However, the relatively high intensity of [Ni3(L)3 + Na+]+ suggests a preference for Na+ by [Ni3(μ3-OCH3)L3] in 3. This result promises that ion-selectivity for Na+ in methanol may be achieved. Indeed it was verified using MS by adding NaCl to methanol solution of 1 (Fig. 5(e), (f) and Supplementary Fig. S3(e), (f)). The spectra showed that the most dominated peaks were the cation exchanged species [NaNi3(L)3]+ at 969.93 (969.90) and its original [LiNi3(L)3]+ at 953.95 (953.92) in positive ion mode; [Ni3(OH)(L)3(H2O)]− at m/z 981.86 (981.92) and its inner bridge switching species [Ni3(OCH3)(L)3]− at 977.92 (977.93) in negative-ion mode. These species indicate [Ni3(OCH3)(L)3]− is acting as an ionophore host with the affinity toward sodium ion. Thus crystal structure of 6, obtained by crystallizing 1 in the presence of NaCl, confirms the exchange of Li+ for Na+.

The present results bridge the gap between solid-state and solution studies and highlight the importance of iterative ESI-MS and X-ray analyses to study reactions in a systematic way (Supplementary Table S3)37. Previous works have so far done very well with the identification of the clusters under study to demonstrate their stability and integrity30. In a few cases, exchange of ions has been shown to take place17. The present study adds another two steps in this progress: firstly, in the field of ESI-MS used for evaluation of host-alkali ions binding selectivity, hosts are dominated by organic38,39. To our knowledge coordination clusters with similar properties remain extremely rare. Secondly, ESI-MS can monitor reactions in-solution while X-ray diffraction identifies and confirm the content of the products found in solution.

The collective effect of the structural changes in the solid-state on the magnetic properties has been monitored by susceptibility measurements as a function of field and temperature (Supplementary Fig. S8–S10, Supplementary Table S4, S5). Clear distinction is found where the exchange interaction changes from being ferromagnetic for compounds with OH− bridge (1 and 5) to antiferromagnetic for those with OCH3− bridges (3, 6 and 7).

Conclusion

In summary, the precursor Ni6Li4 heterometallic cluster has numerous degrees of freedom and undergoes several reactions due to conformational flexibility in abstracting cations of different ionic radii from solutions using its top or bottom claw or both, as evidenced by iterative mass spectrometry in solution and single crystal X-ray crystallography in the solid. This flexibility is chemically driven by the exchange of OH− to OCH3− within the metal moiety and by the electrostatic and geometrical constraints of the organic arms and legs, the cooperative influence of different cations and the supramolecular interactions with solvents or other molecules in the solid. The present study shows that judicious choice of “key” polydentate ligand be used for design of d-s clusters under different stimuli. Furthermore, the ESI-MS and SCXRD complementary approaches can now be extended to investigate the bottom-up processes governing the formation and modification of other cluster systems.

Methods

Materials

All reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used as received. The lithium salt of the ligand 2-[(2-hydroxy-3-methoxy-benzylidene)-amino]-ethane-sulfonic acid (Li2L) was synthesized in an analogous manner to that described previously36.

Measurements

Elemental analyses (C, H, N) were determined with an Elementar vario EL III Analyzer. The FT-IR spectra were recorded from KBr pellets in the range 4000–400 cm−1 on a Bruker Tensor 27 spectrometer. The thermal properties were measured using a gravimetric analyzer (Labsys evo TG-DSC/DTA) under a constant flow of dry nitrogen gas at a rate of 5°C/min. Phase purity was checked by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) at room temperature using a Bruker AXS D8 Advance diffractometer with Cu-Kα radiation. DC Magnetization measurements were performed on polycrystalline samples using a Quantum Design MPMS-XL7 SQUID. Data were corrected for the diamagnetic contribution calculated from Pascal's constants and the sample container.

Synthesis

1 and 2. 1 mmol Li2L was added to 15 mL CH3CN solution of 1 mmol Ni(ClO4)2·6H2O followed by adding 0.5 mL triethylamine. The mixture was stirred and placed in a 25-mL Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 140°C for 72 h. Green block crystals of 1 were collected by filtration. If the mixture was placed in a covered beaker at ambient conditions for 2 days, green block crystals of 2 were isolated by filtration. 3, 4 and 5. The large and well-formed crystals of 1 (0.25 mmol) and 2 (0.25 mmol) were independently dissolved in 10 mL methanol and stirred at room temperature for 10 minutes followed by filtration. The filtrate was allowed to slowly concentrate by evaporation in a small capped-tube at room temperature. Two or seven days later, green needle crystals of 3 (originated from 1) and green block crystals of 4 (originated from 2) were isolated by filtration respectively. If methanol is instead replaced by ethanol in the preparation of 3, green block crystals of 5 were obtained. 6 and 7. Re-crystallizations of 1 (0.25 mmol) and NaCl (0.5 mmol) from methanol results in 6 and of (0.25 mmol) and CaCl2·2H2O (0.5 mmol) gives crystals of 7. Full experimental and X-ray single-crystal diffraction details, synthesis and characterization for all compounds are included in the Supplementary Experimental procedures.

References

Pauling, L. The nature of the chemical bond-1992. J. Chem. Educ. 69, 519–521 (1992).

Zhang, J. P., Zhang, Y. B., Lin, J. B. & Chen, X. M. Metal Azolate frameworks: from crystal engineering to functional materials. Chem. Rev. 112, 1001–1033 (2012).

Yamada, T., Otsubo, K., Makiura, R. & Kitagawa, H. Designer coordination polymers: dimensional crossover architectures and proton conduction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 6655–6669 (2013).

Kawano, M. & Fujita, M. Direct observation of crystalline-state guest exchange in coordination networks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 251, 2592–2605 (2007).

Yin, Z. & Zeng, M. H. Recent advance in porous coordination polymers from the viewpoint of crystalline-state transformation. Sci. China Chem. 54, 1371–1394 (2011).

Horike, S., Shimomura, S. & Kitagawa, S. Soft porous crystals. Nature Chem. 1, 695–704 (2009).

Jacobs, T., Clowes, R., Cooper, A. I. & Hardie, M. J. A chiral, self-catenating and porous metal–organic framework and its post-synthetic metal uptake. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 5192–5195 (2012).

Kolea, G. K. & Vittal, J. J. Solid-state reactivity and structural transformations involving coordination polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 1755–1775 (2013).

Zeng, M. H. et al. Rigid pillars and double walls in a porous metal-organic framework: single-crystal to single-crystal, controlled uptake and release of iodine and electrical conductivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 2561–2563 (2010).

Yin, Z., Wang, Q. X. & Zeng, M. H. Iodine release and recovery, influence of polyiodide anions on electrical conductivity and nonlinear optical activity in an interdigitated and interpenetrated bipillared-bilayer metal−organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 4857–4863 (2012).

Cohen, S. M. Postsynthetic methods for the functionalization of metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 112, 970–1000 (2012).

Sun, F. et al. Tandem postsynthetic modification of a metal–organic framework by thermal elimination and subsequent bromination: effects on absorption properties and photoluminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 4538–4543 (2013).

Meyer, F. & Pritzkow, H. μ4-Peroxo versus bis (μ2-hydroxo) cores in structurally analogous tetracopper(II) complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39, 2112–2115 (2000).

Izzet, G. et al. Supramolecular assemblies with calix[6]arenes and copper ions: from dinuclear to trinuclear linear arrangements of hydroxo–Cu(II) complexes. Inorg. Chem. 45, 1069–1077 (2006).

Fout, A. R. et al. A Co2N2 diamond-core resting state of cobalt(I): a three-coordinate coi synthon invoking an unusual pincer-type rearrangement. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 3291–3295 (2006).

Yang, Y., Pei, X.-L. & Wang, Q.-M. Postclustering dynamic covalent modification for chirality control and chiral sensing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16184–16191 (2013).

Newton, G. N. et al. Trading templates: supramolecular transformations between {CoII13} and {CoII12} nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 790–791 (2008).

Zhou, X. P., Wu, Y. & Li, D. Polyhedral metal-imidazolate cages: control of self-assembly and cage to cage transformation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16062–16065 (2013).

Kilbas, B., Mirtschin, S., Scopellitia, R. & Severin, K. A solvent-responsive coordination cage. Chem. Sci. 3, 701–704 (2012).

Liu, T. F., Chen, Y. P., Yakovenko, A. A. & Zhou, H. C. Interconversion between discrete and a chain of nanocages: self-assembly via a solvent-driven, dimension-augmentation strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17358–17361 (2012).

Pluth, M. D. & Raymond, K. N. Reversible guest exchange mechanisms in supramolecular host-guest assemblies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 36, 161–171 (2007).

Smulders, M. M. J., Riddell, I. A., Browne, C. & Nitschke, J. R. Building on architectural principles for three-dimensional metallosupramolecular construction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 1728–1754 (2013).

Kong, X. J. et al. Keeping the ball rolling: fullerene-like molecular clusters. Acc. Chem. Res. 43, 201–209 (2010).

Zeng, M. H. et al. A single-molecule-magnetic, cubane-based, triangular Co12 supercluster. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 1832–1835 (2007).

Zhou, Y. L. et al. Exploring the effect of metal ions and counteranions on the structure and magnetic properties of five dodecanuclear CoII and NiII clusters. Chem. Eur. J. 17, 14084–14093 (2011).

Martin, F. NMR in Inorganic and Coordination Chemistry (Cambridge International Science Publishing Ltd., Cambridge, 2013).

Venkataramani, S. et al. Magnetic bistability of molecules in homogeneous solution at room temperature. Science 331, 445–448 (2011).

Stephenson, A. et al. Structures and dynamic behavior of large polyhedral coordination cages: an unusual cage-to-cage interconversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 858–870 (2011).

Sun, Q. F., Sato, S. & Fujita, M. An M18L24 stellated cuboctahedron through post-stellation of an M12L24 core. Nature Chem. 4, 330–333 (2012).

Miras, H. N., Wilson, E. F. & Cronin, L. Unravelling the complexities of inorganic and supramolecular self-assembly in solution with electrospray and cryospray mass spectrometry. Chem. Commun. 11, 1297–1311 (2009).

Hu, Y. Q. et al. Tracking the formation of a polynuclear Co16 complex and its elimination and substitution reactions by mass spectroscopy and crystallography. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 7901–7908 (2013).

Zhang, K. et al. Microwave and traditional solvothermal syntheses, crystal structures, mass spectrometry and magnetic properties of CoII4O4 cubes. Dalton Trans. 42, 5439–5446 (2013).

Zhou, Y.-L. et al. Traditional and microwave-assisted solvothermal synthesis and surface modification of Co7 brucite disk clusters and their magnetic properties. Chem. Mater. 22, 4295–4303 (2010).

Wei, L.-Q. et al. Microwave versus traditional solvothermal synthesis of Ni7II discs: effect of ligand on exchange reaction in solution studied by electrospray ionization-mass spectroscopy and magnetic properties. Inorg. Chem. 50, 7274–7283 (2011).

Dalgarno, S. J., Atwood, J. L. & Raston, C. L. Sulfonatocalixarenes: molecular capsule and ‘Russian doll’ arrays to structures mimicking viral geometry. Chem. Commun. 4567–4574 (2006).

Zhang, S.-H. et al. Heterometallic clusters arising from cubic Ni3M′O4 (M′ = K and Na) entity: Solvothermal synthesis with/without the assistance of microwave. J. Solid State Chem. 182, 2991–2996 (2009).

Riddell, I. A. et al. Anion-induced reconstitution of a self-assembling system to express a chloride-binding Co10L15 pentagonal prism. Nature Chem. 4, 751–756 (2012).

Schalley, C. A. Molecular recognition and supramolecular chemistry in the gas phase. Mass Spectrometry Reviews. 20, 253–309 (2001).

Di Marco, V. B. & Bombi, G. G. Electrospray mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) in the study of metal–ligand solution equilibria. Mass Spectrometry Reviews. 25, 347–379 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NSFC (No. 91022015, 91122032, 21371037), Guangxi Province Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scientists (2012GXNSFFA060001), the Project of Talents Highland of Colleges and Universities in Guangxi Province and the CNRS-France.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.-H.Z. devised the initial concept for the work. M.-H.Z. and K.Z. designed the experiments. K.Z. and L.-Q.W. performed the experiments and analysed the data. M.-H.Z., M.K. and K.Z. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, K., Kurmoo, M., Wei, LQ. et al. Iterative Mass Spectrometry and X-Ray Crystallography to Study Ion-Trapping and Rearrangements by a Flexible Cluster. Sci Rep 3, 3516 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03516

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03516

This article is cited by

-

Crystallography and Mass-Spectrometry of Heptanuclear Disk Mn(II) Cluster

Journal of Cluster Science (2022)

-

Topological insights in polynuclear Ni/Na coordination clusters derived from a schiff base ligand

Structural Chemistry (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.