Abstract

Transition metal-based lithium orthosilicates (Li2MSiO4, M = Fe, Ni, Co, Mn) are gaining a wide interest as cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. These materials present a very complex polymorphism that could affect their physical properties. In this work, we synthesized the Li2FeSiO4 and Li2MnSiO4 compounds by a sol-gel method at different temperatures. The samples were investigated by XRPD, TEM, 7Li MAS NMR and magnetization measurements, in order to characterize the relationships between crystal structure and magnetic properties. High-quality 7Li MAS NMR spectra were used to determine the silicate structure, which can otherwise be hard to study due to possible mixtures of different polymorphs. The magnetization study revealed that the Néel temperature does not depend on the polymorph structure for both iron and manganese lithium orthosilicates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polyanion framework compounds based on PO4 or SiO4 structural units are now under intense study for the application as cathode materials in lithium-ion batteries. All of these materials are characterized by low costs and toxicity, are environmentally friendly and highly safe1. Along with the well-known phospho-olivine, lithium orthosilicates appear especially promising because they can afford more than one electron reversible exchange per transition metal atom, so increasing the overall cathode capacity. In fact, Li2MnSiO4 can reach the capacity of 333 mAhg−1, while Li2FeSiO4 could deliver 166 mAhg−1 for the extraction of one Li ion2. However, the low electronic conductivity of silicates has to be overcome in order to reach the theoretical capacity and different approaches have been tried to improve their electrochemical performances, e.g. by mixing Fe and Mn3,4,5,6, by doping with Cr7, V8, Mg9, Zn, Cu and Ni10, by adding a proper carbon-coating11 or by preparing composites with carbon nanotubes12.

Another critical feature of the orthosilicates is their rich polymorphism with numerous, different crystal structures that could be stabilized depending on the synthesis conditions13. Usually, the monoclinic P21/n and the orthorhombic Pmn21 or Pmnb space groups are reported for both the Li2MnSiO4 and Li2FeSiO4 compounds. The differences among these structures are mainly due to different arrangements of the cation tetrahedra and local-order probes such as solid-state Magic Angle Spinning Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (MAS NMR) are very useful to identify the obtained polymorphs and also mixtures of them14. This rich polymorphism, with the associated small transition energies, is one of the factors affecting the long-term cyclability of these materials. We recently showed by density-functional theory (DFT) calculations that, under delithiated conditions, Li2MnSiO4 can transform from the Pmn21 or Pmnb polymorphs to the electrochemically weakest P21/n one and this mechanism may gradually lead to electrochemical and structural collapse15.

The dependence of Li2FeSiO4 electrochemistry on structure was also recently investigated16,17, while information regarding polymorphism and magnetic properties is still lacking. Some works report about the antiferromagnetic (AFM) magnetic ordering temperature of Li2MSiO4 (M = Co, Mn, Fe) and the magnetic measurements were mainly used to probe the presence of ferro or ferri-magnetic impurities in the samples1,18,19. In this work we report the results of the magnetic and spectroscopic study of Li2MSiO4 (M = Fe, Mn), prepared via sol-gel synthesis at different temperatures to obtain different polymorphs. The magnetic properties are investigated by SQUID magnetometry and their relationships with the polymorph structure are discussed. The combined use of X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD) and 7Li MAS NMR allowed us to individuate the phases in the samples. TEM microscopy coupled with Selected Area Electron Diffraction (SAED) was also used as a helpful tool for the assignment of the correct structure to the synthesized materials.

Results

XRPD and Rietveld results

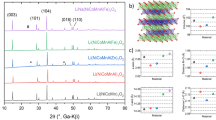

Figures 1a and b show, for comparison, the XRPD patterns of the Li2FeSiO4 and Li2MnSiO4 samples, respectively. The Li2FeSiO4 samples present low amount of different impurities, which can be identified as Fe3O4 (JCPDS card No. 19-0629), Li3Fe5O8 (JCPDS card No. 74-1754) and FeO (JCPDS card No. 89-0687). Besides, other differences in the patterns can suggest the presence of different silicate polymorphs. For the Li2MnSiO4 samples the main impurities are Li2SiO3 (JCPDS card No. 29-0828) and MnO (JCPDS card No.75-1090) and again some pattern differences can be ascribed to the formation of different polymorphs. The Fe samples show a higher degree of purity than the Mn ones (see also Table 1), suggesting that under these synthesis conditions iron silicates can be obtained more easily than the Mn ones.

The Rietveld refinements were performed on the basis of the structural models present in the literature, that take into account the existence of different polymorphs6,20. The results of the Rietveld refinements are reported in Table 1 together with the discrepancy factors. Rwp and S are satisfactory and suggest a good quality of the structural refinement. Different synthesis conditions allowed the stabilization of different polymorphs, as evidenced both for the Li2FeSiO4 and Li2MnSiO4 compounds. In fact, for the Fe compound synthesized at low temperature the monoclinic P21/n s.g. was obtained (see Rietveld refinement in Figure 1c), while at 900°C the Pmnb space group provided a good description of the structure of the sample. The s.g. assignment depends on some typical reflections, i.e. the peak at about 20°/2θ, distinctive of the Pmnb s.g. and the peak at 31.8°/2θ that otherwise pertains to the P21/n s.g. In addition, the P21/n structure presents three peaks in the range 20–23.5°/2θ, while only two peaks are found in the same region for the orthorhombic form.

For the Mn compounds, a co-presence of polymorphs was found for the Mn-900, including Pmnb and P21/n phases. In case of Mn-650, the Pmn21 structure was found as a single phase.

NMR results

The NMR spectroscopy of these materials is traditionally challenging since the paramagnetic transition-metal ions induce very large shifts and shift anisotropies, resulting in spectra that are very broad and difficult to excite using standard NMR methods. However, the combined use of ultra-fast MAS (60 kHz) and sophisticated pulse sequences enabled us to obtain extremely high-quality broadband 7Li spectra with a short experiment time of about 16 minutes per spectrum. Figure 2 reports the full 7Li MAS NMR spectra of the Mn-650 and Fe-650 samples (parts a and b, respectively). Both spectra are characterized by broad spinning-sideband manifolds which are due to the hyperfine interactions between the unpaired electrons of the transition metal ion and the observed nucleus21. The unpaired electrons of the tetrahedrally-coordinated high-spin Mn2+ ion are present in the configuration eg2t2g3, giving an isotropic g-tensor whose value is equal to the free-electron g-value ge. In this case, the isotropic contribution to the paramagnetic shift is due to the Fermi-contact interaction (and is referred to as the Fermi-contact shift) and the spinning sidebands arise from the spin-dipolar interaction between the unpaired electrons and the nucleus. The interactions giving rise to the paramagnetic 7Li shift for Li2FeSiO4 are more complicated, as the high-spin Fe2+ electron configuration of eg3t2g3 gives an anisotropic g-tensor due to spin-orbit coupling. In addition to the Fermi-contact interaction, the isotropic shift now has a contribution from the pseudo-contact shift, which is due to the coupling of the g-anisotropy to the spin-dipolar term in the hyperfine coupling tensor. For a detailed description of the Hamiltonian terms describing these spectra see refs22,23.

In addition, the g-anisotropy can be used to rationalize the difference in the linewidths of the sidebands in each spectrum. The increased broadening in the spectrum of Fe-650 relative to Mn-650 is entirely inhomogeneous and arises from the anisotropic bulk magnetic susceptibility (ABMS) due to the g-anisotropy in the former material14,24,25. It should be noted that the differences in linewidth cannot be explained by the differences in the homogeneous contributions, such as spin-spin relaxation. We measured the 7Li homogeneous decay time constants T2′ for both samples, which were found to be 497 μs and 720 μs for Mn-650 and Fe-650, respectively. The corresponding homogeneous linewidth 442 Hz for Fe-650 is therefore found to be lower than the value of 640 Hz for Mn-650. The linewidth in the spectrum of Fe-650 is therefore dominated by the inhomogeneous contribution.

Figure 3 shows an expansion of the spectral region containing the isotropic peaks, which were identified using the recently-published adiabatic magic-angle turning (aMAT) experiment26, together with their best-fits whose results are reported in Table 2. In order to check the sensitivity of our approach, we performed different best-fits by including, beside the isotropic peaks, also up to three couples of spinning sidebands, but the overall agreement did not change significantly and the ratios among the different components change of about 10–15%.

The spectrum of Mn-650 is characterized by the presence of three peaks at 2.5 ppm, −98.1 ppm and −120.2 ppm (Figure 3a). The downfield peak is attributed to the Li2SiO3 diamagnetic impurity and accounts for 9.8% of the total observed lithium, in reasonable agreement with the 15.6% obtained by the Rietveld analysis (see Table 1). The peaks upfield are attributed to the Pmnb (−98.1 ppm) and Pmn21 (−120.2 ppm) polymorphs, respectively, in agreement with the literature assignments13,27. The Pmnb accounts for about 10% of the overall active phase. We stress here that further Rietveld refinements performed by using both Pmnb and Pmn21 polymorphs gave us only a marginal improvement of the fit for the Mn-650 sample with respect to that reported in Table 1 (see Discussion). On the other hand, the reflections of Pmnb and Pmn21 polymorphs are very similar. The spectrum of Fe-650 (Figure 3b) is characterized by two peaks at −8.7 ppm and −52.0 ppm, which can be attributed at the two Li sites of the P21/n polymorph, in good agreement with the assignment of Sirisopanaporn et al.20. By considering the spinning sidebands and therefore the different shift anisotropies, the best-fitted ratio between the two sites is 56:44. No evidence of diamagnetic impurities or other Li-containing active phases is observed, in agreement with the Rietveld refinement.

SEM and TEM

SEM analysis showed that for the samples synthesized by sol-gel at 650°C the morphology was constituted by aggregates of small rounded particles, whereas at 900°C the samples appeared to be constituted by large agglomerates of fused particles. SEM micrographs of the as-prepared samples are shown in Figure S1 (ESI).

In order to verify the polymorph assignments obtained by XRPD and NMR, TEM analysis was also performed. However, the measurements to investigate the crystalline structure were performed only on the Fe-900 specimen (Figure 4a), because the samples synthesized at 650°C showed crystallite aggregation (see Figure S2). From the morphological point of view, the sample comprises rounded particles with diameters ranging from approximately 0.2 to 0.5 μm. In general, the particles were too thick to give enough contrast for High Resolution Electron Microscopy. In order to obtain information about the crystallographic structure, therefore, we performed Selected Area Electron Diffraction (SAED) on single grains after orienting them along some low order Zone Axis (ZA). A representative SAED is reported in Figure 4b. To check which space group was responsible for the diffraction patterns many image simulations were performed using the JEMS software28. All the ZAs were calculated for both the space groups P21/n and Pmnb. The best result, obtained for the Pmnb space group with the crystal oriented along [011], is reported in Figure 4c, where the simulated electron diffraction pattern is superimposed to the experimental one.

(a) TEM micrograph and (b) SAED of the specimen Fe-900; (c) The same experimental pattern (SAED), as reported in Figure b, together with simulated Electron Diffraction pattern; the Miller indexes are also indicated.

The drawing makes use of the kinematical theory of electron diffraction. The intensity of the spots is just proportional to their structure factor (bright red spots correspond to higher structure factors while black spots correspond to lowest structure factors). The Double diffraction spots are also indicated in yellow.

Magnetic characterization

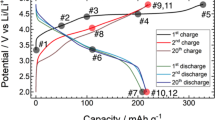

Figure 5a shows the temperature dependence of the magnetization (M/H vs. T curves) for the Fe-900 and Fe-650 samples in zero field cooling (ZFC) and field cooling (FC) regimes, obtained by applying a 10000 Oe magnetic field. Both the samples undergo the paramagnetic to antiferromagnetic transition, with Néel temperature TN ≅ 20 K, typically observed for the lithium iron silicate1,18. Deviations from the usual Curie-Weiss behaviour emerge from Figure 5a: a markedly higher M value pertains to the Fe-650 sample, with respect to the Fe-900 one, in the whole investigated temperature range, while a clear-cut separation between ZFC and FC curves is observed, for temperatures lower than about 50 K, only for the Fe-900 sample. The field dependence of the magnetization, investigated at different temperatures, allowed us to verify the origin of these peculiar features. Figure 5b shows the M vs. H curves for Fe-900 and the fit of the linear part of each curve; experimental curves at room temperature, together with their linear fit, for Fe-900 and Fe-650 are instead compared in the inset.

(a) ZFC and FC temperature dependence of molar magnetization at 10000 Oe for Fe-900 (black line) and Fe-650 (red line) samples. (b) M vs H curves for Fe-900 at different temperatures. The linear fit of the high field region is also shown. Inset: comparison between room temperature M vs H curves of Fe-900 (black symbols) and Fe-650 (red symbols) samples, reported with their linear fits (black lines). (c) ZFC and FC M vs T curves at 10000 Oe for Mn-900 (black) and Mn-650 (red) samples. Inset: FC curves in the low temperature region.

The non-linear M(H) behaviour evident for Fe-900 at 5 K for low magnetic fields suggests the presence of a ferromagnetic-like extrinsic contribution, with a value of magnetization at null field, MS(H = 0), obtained by extrapolating the linear behaviour at high fields and corresponding to the residual magnetization of such ferromagnetic-like ordered phase, of about 45 emu/mol. This value decreases with increasing the temperature, becoming negligible at r.t. A linear behaviour is indeed generally observed for T ≥ 50 K and H ≥ 500 Oe. The non-null MS(H = 0) contribution plausibly arises from the impurity phase disclosed by XRPD data, i.e. Li3Fe5O8, for which a ferro- or ferri-magnetic behaviour can be reasonably supposed. This assumption is well supported by quantum-mechanical calculations29, which, taking into account magnetic interactions, foresee an arrangement of Fe atoms, in the structure of Li3Fe5O8, compatible with both ferromagnetic and ferrimagnetic orderings, being the ferrimagnetic arrangement energetically favoured. Incidentally, we remark that the MS(H = 0) value here obtained at 5 K corresponds to about 1 Bohr magneton per unit formula, indeed supporting a ferrimagnetic ordering for this phase. The small amount of Li3Fe5O8 in the sample can also be responsible of the separation between ZFC and FC M vs. T curves (see Figure 5a).

A M(H) non-linear behaviour at low magnetic fields is instead always detected for the Fe-650 sample, with a MS(H = 0) value ranging between 135 and 140 emu/mol, in the whole T range. This value corresponds to the additive contribution to the M vs. T curve pertaining to the Fe-650 sample, shown in Figure 5a. We can undoubtedly attribute this additive contribution to the ferrimagnetic Fe3O4 phase, detected by XRPD in this sample in very small amount, whose TC value is much higher than r.t.30. Taking into account the MS value of this phase (92 emu/g at r.t.31), the amount of Fe3O4 in Fe-650, as revealed by the saturation magnetization values, results to be in very good agreement with the XRPD data (Table 1). No sign of the antiferromagnetic (AF) transition of the small amount of FeO phase (TN ≈ 186–198 K30), disclosed by XRPD, is instead detectable in the M vs. T curve of Fe-650.

In order to avoid the contribution of saturated magnetic phases, Curie-Weiss constants for our lithium iron silicates have been inferred considering the 1/χmol(T) values obtained from the slopes of the linear part of the M vs. H curves at different temperatures (χ(T) = dM(T)/dH, T = 300, 200, 100, 50, 5 K) in the T range corresponding to the linear paramagnetic region.

For Fe-650 the obtained Curie constant leads to an effective magnetic moment, μeff, for the iron silicate very near to 5 μB, thus consistent with a spin only contribution of Fe2+ in the high spin configuration. Besides, a Weiss constant, θ, of about −35 K has been obtained. We remark that these values and the related TN value, are in very good agreement with those reported in the literature for this compound1. A higher μeff value has instead been obtained for Fe-900 (μeff ≅ 5.15), which could imply, for example, the contribution, in addition to the one of divalent iron ions, from Fe ions with higher oxidation state. Nevertheless, this should not be the case because a TN value of 20 K in this compound is related to magnetic interactions between Fe2+ spins only, while the coexistence of Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions should give rise to AF ordering with a TN value higher than 20 K32. On this basis, an extrinsic contribution can be instead invoked to explain the higher estimated μeff value for Fe-900, as, for example, the one due to the small amount in the sample of the ferrimagnetic Li3Fe5O8 phase not fully saturated in the whole temperature range considered to estimate Curie and Weiss constants. Moreover, it must be taken into account that even a small amount of ferromagnetic-like impurity phase can enhance the |θ| value of the sample. Indeed, for Fe-900 a higher |θ| value (θ = −60 K) has been estimated with respect to Fe-650, against the unchanged TN value of the iron silicate phase.

In view of the small amount of well-characterized impurity phases in the samples, magnetization data attest the good quality and stoichiometry of the lithium iron silicate phases.

The magnetic characterization of Li2MnSiO4 samples is affected by the presence, together with the silicate, of a great amount of spurious phases, both Li-/Si- based compounds, diamagnetic and manganese oxide, characterized by a paramagnetic-to-antiferromagnetic transition with a TN value (112–115 K30) falling inside the investigated temperature range. Figure 5c reports the ZFC and FC temperature dependence of the molar magnetization at 10000 Oe for the two investigated samples. Both of them clearly display the typical Li2MnSiO4 paramagnetic to antiferromagnetic transition with Néel temperature TN ≅ 12 K1,33. A small, but not negligible difference between the TN values is evident in the enlargement of the FC curves, reported in the inset of Figure 5c. In particular, a lower value (≅11 K) is detected for the sample synthesized at the lower temperature. No sign of the AF transition related to the manganese oxide is detectable in the M vs. T curves at the foreseen TN value even for Mn-650, for which a remarkable MnO amount is indeed disclosed by XRPD.

The Curie-Weiss constants have been extracted from 1/χmol(T) values in the high temperature paramagnetic region. The contribution of the MnO impurity phase to the overall paramagnetic behaviour of the samples has been taken into account to try to estimate the μeff values for the main lithium manganese silicate phase. For Li2MnSiO4 in Mn-900, μeff is found to be near to 6 μB, consistently with a spin only contribution of Mn2+ in high spin configuration. A θ value of about −35 K has been obtained for this sample. These values are in fair agreement with those reported in literature for the manganese lithium silicate1,33.

For the Mn-650 sample a higher |θ| value has been obtained with respect to Mn-900, consistently with the presence of a much higher MnO amount, for which the antiferromagnetic interactions are stronger with respect to the silicate phase. Besides, a μeff value appreciably lower than 6 μB has been inferred in this case and, although this estimate can be strongly affected by the low purity of the sample, it seems however to suggest the presence, together with divalent manganese ions, of an appreciable amount of Mn ions with higher oxidation states in the Li2MnSiO4 phase.

Discussion

The combined use of XRPD and 7Li MAS NMR allowed us to recognize the stable polymorphs for the lithium iron/manganese silicates synthesized at the different temperatures. The main difference between the two series of samples concerns the possibility of obtaining a single phase for Li2FeSiO4 independently of the synthesis temperature, while Li2MnSiO4 was obtained as a single polymorph only at 650°C. Besides, in the case of Li2MnSiO4 we observe the stabilization of the Pmnb polymorph at 900°C in agreement with the findings of Gummow et al.34, who recently discussed the formation of the Pmnb structure for the Li2MnSiO4 material synthesized at 900°C, with a different connectivity of LiO4 and MnO4 tetrahedra with respect to the Li2FeSiO4 Pmnb polymorph.

We remark that 7Li MAS NMR was chiefly used to check that the polymorphs found by XRD Rietveld analysis were correct, in particular for the samples which where found to be single phase. A very good agreement was found for the Fe-650 sample, while some discrepancies were observed in the case of Mn-650. At first, the Rietveld refinement was carried out by considering only the Pmn21 structure but, on the basis of the NMR results, the Pmnb one was also considered afterwards. In fact, a slight improvement of the fitting was obtained (Rwp 11.6 vs. 12.9) and the amount of the Pmnb phase was 15%, in reasonable agreement with the about 10% value obtained by NMR. At the light of these results, we believe that XRPD cannot easily discriminate between so similar phases, such as the Pmn21 and Pmnb polymorphs and that the parallel use of a powerful local probe such as 6,7Li MAS NMR is mandatory.

Once the crystal structures of the samples have been precisely determined, the relationship between the polymorphic form and the physical properties was investigated. In particular, we focused our attention on the magnetic properties. We recall that the antiferromagnetic ordering in Li2MSiO4 comes from the long-range M-O-Li-O-M interactions1. Our data, in addition to what reported in the literature1, do support the hypothesis that the structural differences between the different polymorphs is too small to affect the interaction paths to such an extent that the TN value may change. Indeed, as already discussed, the same TN value was detected for the lithium iron silicate phase in Fe-650 and Fe-900, which are characterized by the monoclinic P21/n and the orthorhombic Pmnb polymorphs, respectively. Moreover, the same TN value was also detected for the orthorhombic Pmn21 lithium iron silicate1,19. Then, a clear correlation cannot be found between polymorphism and magnetic features of Li2FeSiO4. Rather, the TN value of the lithium iron silicates can be influenced by the coexistence between Fe ions with different oxidation states32. Also the results shown above for the Li-Mn silicates are in agreement with these hypotheses: the small TN shift from 12 K (i.e. from the value commonly reported in literature for stoichiometric Li-Mn silicates1,33) is indeed observed for the sample for which the coexistence of Mn2+ ions with manganese ions with different oxidation states has been disclosed.

In conclusion, Li2FeSiO4 and Li2MnSiO4 compounds were synthesized by a sol-gel route and the polymorphic form and impurity phases were investigated by using XRPD, 7Li MAS NMR and magnetization measurements. The magnetic analysis was applied to obtain information not only on the general presence of ferro- or ferrimagnetic impurities, but also to verify their nature and quantify them. Besides, the study of the silicate magnetic features allowed us to rule out the dependence of the TN on the polymorphism.

A new procedure of 7Li NMR spectra collection was applied, based on the combined use of very fast MAS rotation and sophisticated pulse sequences. The clear advantage of using 7Li with respect to the less abundant 6Li and obtaining similar quality or even better spectra, is the possibility to manage very much shorter acquisition times which open the door to in situ experiments. Our high-quality spectra allowed us to put into evidence the presence of mixture of polymorphs in the case of the lithium manganese silicate, hardly identifiable by XRPD, thus confirming that solid state NMR is a powerful tool to investigate such subtle differences in lithium orthosilicates.

Methods

Synthesis

The Li2MSiO4 (M = Fe, Mn) samples were prepared by sol-gel synthesis. FeC2O4·2H2O (Aldrich 99.99+%) or Mn(CH3COO)2·4H2O (Aldrich 99+%), LiCOOCH3·2H2O (Fluka >99%) and TEOS (Sigma-Aldrich 98%) in stoichiometric ratios were dissolved in ethanol and the solution was stirred at 50°C until the solvent evaporation. The precursor was dried in a muffle at 80°C overnight and then treated in argon atmosphere at 650°C or 900°C for 8 h6. The sol-gel samples prepared at 650 and 900°C are named Fe-650, Fe-900, Mn-650 and Mn-900.

Characterization techniques

In-house X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD) measurements were performed using a Bruker D5005 diffractometer with the CuKα radiation, graphite monochromator and scintillation detector. The patterns were collected with a step size of 0.02° and counting time of 10 s per step in the angular range 15–100°/2θ.

Rietveld structural and profile refinement was carried out by means of TOPAS V3.0 program35. During the refinement, lattice parameters, isotropic thermal factors, atomic positions were allowed to vary. The weight percentage of the impurity phases was also determined.

SEM measurements were performed with a Zeiss EVO®-MA10-HR microscope on Au-sputtered samples.

TEM measurements were performed on a JEOL-JEM3010 microscope operating at 300 kV and having a point-to-point resolution of 1.7Å. The specimens were sonicated in isopropyl alcohol, a drop was deposited on a holey carbon copper grid and let to evaporate at room temperature and then the grid was transferred into the microscope.

The 7Li MAS NMR data were acquired with a Bruker Avance III spectrometer at a field of 11.7 T, operating at a Larmor frequency of 194 MHz, equipped with an HX 1.3 mm probe. The spectra were recorded under 60 kHz MAS using a double-adiabatic spin-echo sequence employing a pair of tanh/tan short high-powered adiabatic pulses (SHAPs)36, each of duration 50 μs and radiofrequency field amplitude 455 kHz. For each spectrum 16384 scans were acquired with a recycle delay of 50 ms, giving a total experiment time of 16 minutes. The chemical shift scale was referenced relative to the 7Li resonance in LiF. The time constants T2′ describing the homogeneous decay of the transverse magnetization were determined using the same pulse sequence. The best-fits were performed with the Sola routine of Topspin® (Bruker), by including the isotropic peaks and four spinning sidebands in order to obtain an estimate of the chemical shift anisotropy.

The magnetic field dependence of magnetization, M(H), was investigated by means of a Quantum Design Squid magnetometer, at different temperatures with magnetic field ranging between 0 and 50 000 Oe. M vs. T curves have been also collected in the range 2–300 K applying a 10 000 Oe magnetic field, chosen in the field region where a linear M(H) dependence was observed for all the samples.

References

Gong, Z. et al. Recent advances in the research of polyanion-type cathode materials for Li-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 3223–3242 (2011).

Nyten, A. et al. Electrochemical performance of Li2FeSiO4 as a new Li-battery cathode material. Electrochem. Commun. 7, 156–160 (2005).

Guo, H. et al. Optimum synthesis of Li2Fe1−xMnxSiO4/C cathode for lithium ion batteries. Electrochimica Acta 5, 8036–8042 (2010).

Dominko, R. et al. On the Origin of the Electrochemical Capacity of Li2Fe0.8Mn0.2SiO4 . J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, A1309–A1316 (2010).

Kokalj, A. et al. Beyond One-Electron Reaction in Li Cathode Materials: Designing Li2MnxFe1−xSiO4 . Chem Mater. 19, 3633–3640 (2007).

Bini, M. et al. Insight into cation disorder of Li2Fe0.5Mn0.5SiO4 . J. Solid State Chem. 200, 70–75 (2013).

Zhang, S. et al. Effects of Cr doping on the electrochemical properties of Li2FeSiO4 cathode material for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochimica Acta 55, 8482–8489 (2010).

Li, Y. et al. Achieving High Capacity by Vanadium Substitution into Li2FeSiO4 . J. Electrochem. Soc. 159, A69–A74 (2012).

Zhang, S. et al. Doping effects of magnesium on the electrochemical performance of Li2FeSiO4 for lithium ion batteries. J. Electroanalytical Chemistry 644, 150–154 (2010).

Deng, C. et al. Synthesis and characterization of Li2Fe0.97M0.03SiO4 (M = Zn2+, Cu2+, Ni2+) cathode materials for lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 19, 386–392 (2011).

Moskon, J. et al. Morphology and electrical properties of conductive carbon coatings for cathode materials. J. Power Sources 174, 683–688 (2007).

Huang, X. et al. Synthesis and electrochemical performance of Li2FeSiO4/carbon/carbon nano-tubes for lithium ion battery. Electrochimica Acta 55, 7362–7366 (2010).

Islam, M. S. et al. Silicate cathodes for lithium batteries: alternatives to phosphates? J. Mater. Chem. 21, 9811–9818 (2011).

Mali, G. et al. Understanding (6)Li MAS NMR spectra of Li(2)MSiO(4) materials (M = Mn, Fe, Zn). Solid State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance 42, 33–41 (2012).

Kalantarian, M. M. et al. Theoretical investigation of Li2MnSiO4 as a cathode material for Li-ion batteries: a DFT study. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 2847–2855 (2013).

Eames, C. et al. Insights into Changes in Voltage and Structure of Li2FeSiO4 Polymorphs for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Chem. Mater. 24, 2155–2161 (2012).

Sirisopanaporn, C. et al. Dependence of Li2FeSiO4 Electrochemistry on Structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 1263–1265 (2011).

Zaghib, K. et al. Structural, magnetic and electrochemical properties of lithium iron orthosilicate. J. Power Sources 160, 1381–1386 (2006).

Gong, Z. L. et al. Nanostructured Li2FeSiO4 Electrode Material Synthesized through Hydrothermal-Assisted Sol-Gel Process Batteries and Energy Storage. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 11, A60–A63 (2008).

Sirisopanaporn, C. et al. Polymorphism in Li2(Fe,Mn)SiO4: A combined diffraction and NMR study. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 17823–17831 (2011).

Mustarelli, P. et al. Transferred hyperfine interaction and structure in LiMn2O4 and Li2MnO3 coexisting phases: a XRD and 7Li NMR-MAS study. Phys. Rev. B 55, 12018–12024 (1997).

Capsoni, D. et al. Cations distribution and valence states in Mn-substituted Li4Ti5O12 structure. Mater. Chem. 20, 4298–4291 (2008).

Pennanen, T. O. et al. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Chemical Shift in an Arbitrary Electronic Spin State. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 133002 (2008).

Alla, M. et al. Resolution limits in magic-angle rotation NMR spectra of polycrystalline solids. Chem. Phys. Lett. 87, 30–33 (1982).

Kubo, A. et al. The Effect of Bulk Magnetic Susceptibility on Solid State NMR Spectra of Paramagnetic Compounds. J. Magn. Reson. 133, 330–340 (1998).

Clement, R. J. et al. Spin-Transfer Pathways in Paramagnetic Lithium Transition-Metal Phosphates from Combined Broadband Isotropic Solid-State MAS NMR Spectroscopy and DFT Calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17178–17185 (2012).

Mali, G. et al. 6Li MAS NMR spectroscopy and first-principles calculations as a combined tool for the investigation of Li2MnSiO4 polymorphs. Chem. Commun. 46, 3306–3308 (2010).

Stadelmann, P. JEMS software, CIME-EPFL, CH-1015 Lausanne.

Catti, M. et al. First-principles modelling of lithium iron oxides as battery cathode materials. J. Power Sources 196, 3955–3961 (2011).

Craik, D. J. Magnetic Oxides Part 1, John Wiley & Sons, London, 29–32 (1975).

Azzoni, C. B. et al. New insights into the magnetic properties of the Ca2Fe2O5 ferrite. Solid State Sci. 9, 515–520 (2007).

Lee, I. K. et al. Mössbauer analysis of silicate Li2FeSiO4 and delithiated Li2−xFeSiO4 (x = 0.66) compounds. J. Appl. Phys. 113, 17E306 (2013).

Belharouak, I. et al. Structural and Electrochemical Characterization of Li2MnSiO4 Cathode Material. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 20733–20737 (2009).

Gummow, R. J. et al. Crystal chemistry of the Pmnb polymorph of Li2MnSiO4 . J. Solid State Chem. 188, 32–37 (2012).

Bruker AXS. TOPAS V3.0: General profile and structural analysis software for powder diffraction data. User Manual Bruker AXS, Karlsruhe, Germany, 2005.

Kervern, G. et al. Fast adiabatic pulses for solid-state NMR of paramagnetic systems. Chem Phys Lett. 435, 157–162 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This work is performed in the frame of Cariplo Project 2011-0325 “New electrolyte and electrode materials for thin-film lithium microbatteries”. A.J.P. and G.P. acknowledge financial support from the LABEX iMUST framework (ANR-10-LABX-0064) of the Université de Lyon, within the program “Investissements d'Avenir” (ANR-11-IDEX-0007) which is operated by the French National Research Agency (ANR). C.F. acknowledges a fellowship from the French Ministry for the Foreign Affairs (dossier n. 781569G).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C.M. performed the magnetic measurements with related data analysis and wrote the magnetic section. C.F., A.J.P., G.P. and P.M. collected and analysed the NMR spectra. P.C. performed TEM analysis. M.B., S.F., D.C. performed XRPD analysis. S.F. performed the synthesis. M.B. and S.F. wrote the manuscript and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supporting information contains SEM and TEM images

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Bini, M., Ferrari, S., Ferrara, C. et al. Polymorphism and magnetic properties of Li2MSiO4 (M = Fe, Mn) cathode materials. Sci Rep 3, 3452 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03452

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03452

This article is cited by

-

Emerging Atomic Layer Deposition for the Development of High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries

Electrochemical Energy Reviews (2023)

-

New materials for Li-ion batteries: synthesis and spectroscopic characterization of Li2(FeMnCo)SiO4 cathode materials

Scientific Reports (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.