Abstract

Microbial biofilms, prevalent in nature and inherently resistant to both antimicrobial agents and host defenses, can cause serious problems in the chemical, medical and pharmaceutical industries. Herein we demonstrated that conjugation of an aminoglycoside antibiotic (streptomycin) to chitosan could efficiently damage established biofilms and inhibit biofilm formation. This method was suitable to eradiate biofilms formed by Gram-positive organisms and it appeared that antibiotic contents, molecular size and positive charges of the conjugate were the key to retain this anti-biofilm activity. Mechanistic insight demonstrated chitosan conjugation rendered streptomycin more accessible into biofilms, thereby available to interact with biofilm bacteria. Thus, this work represent an innovative strategy that antibiotic covalently linked to carbohydrate carriers can overcome antibiotic resistance of microbial biofilms and might provide a comprehensive solution to combat biofilms in industrial and medical settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microorganisms on living or inert surfaces usually form organized multi-cell aggregates in a self-produced hydrated extracellular matrix, namely microbial biofilms. The failure in the prevention and eradiation of microbial biofilms might create a number of serious problems such as industrial fluid processing operations (bio-deterioration)1, food safety (contamination)2 and public health issues (infectious diseases)3.

Biofilm formation makes microbes more resistant to stresses, acids, antibiotics and immune clearance when compared to planktonic cells4,5. A list of factors have been attributed to this resistance including restricted penetration of antimicrobials into biofilms, decreased growth rate and expression of possible resistance genes6,7. Bypassing antibiotic treatments, new efforts for biofilm growth inhibition, biofilm damage, or biofilm eradication are being sought. These include bacteriophage8, enzymes9, metal nanoparticles10, plant extracts11 and chitosan derivatives12,13, all of which have been shown to influence biofilm structures with different efficiencies via various mechanisms.

Chitosan, the N-deacetylated derivative of chitin, is a polycationic macromolecules composed of randomly distributed β-(1-4)-linked D-glucosamine and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine. As a biomaterial, chitosan has a track record for its inherent antimicrobial properties against a broad spectrum of organisms14,15. Also, chitosan exhibits anti-biofilm activities and the ability of chitosan to damage biofilms formed by microbes has been documented12,13. Among several mechanisms involved16,17,18, chitosan has been shown to penetrate biofilms due to the ability of cationic chitosan to disrupt negatively charged cell membranes as microbes settle on the surface17,18.

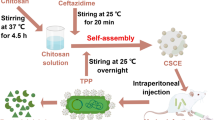

The present study was to describe an innovative strategy to combat forming or preformed microbial biofilms by using chitosan as a covalent carrier for an aminoglycoside antibiotic, streptomycin. The conjugateswere synthesized after the reduction of Schiff base formed by chitosan and streptomycin, an aminoglycoside antibiotic19. The anti-biofilm efficacy of conjugates was evaluated towards Gram-positive or -negative organisms. Structural requisite and mechanistic insights for their anti-biofilm capacity were addressed.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of chitosan-streptomycin (C − S) conjugates

The conjugation between streptomycin and chitosan was achieved by reduction of the resulting Schiff base formed by free animo groups in chitosan and aldehyde groups in streptomycin (Figure 1A), as described20. The coupling between streptomycin and chitosan was evidenced by 1H NMR analysis and streptomycin contents in C − S conjugates were further determined through quantification of guanidyl groups21. The 1H NMR of one representative C − S conjugate which contains 32% (w/w) streptomycin and was derived from chitosan (Mw = ~13 kDa) was presented (Figure S1). The disappearance of weak signals at 9.66 ppm (aldehyde proton) and appearance of strong signals at 1.22 ppm (methyl protons) in the extensively dialyzed polymer confirmed the linkage between streptomycin and chitosan successful.

C − S conjugate disrupted preformed L. monocytogenes biofilms with a high efficiency.

The synthesis of C − S was achieved by the reductive amination between streptomycin and chitosan (A). Biofilms were exposed to 0.25 mg/mL C − S conjugate (23% streptomycin, ~13 kDa chitosan), equivalent chitosan (C) or streptomycin (S) alone and the respective mixture (C + S) for hours indicated. Biofilms incubated in TSB containing phosphate-buffered saline were used as control. Biofilm mass (B) and viable cells (C) were quantified and biofilm architectures after 24 h treatment were examined by scanning electron microscopy (D) and fluorescence microscopy (E). These experiments were performed three times with similar results each time. Error bars represent SD.

C − S conjugates broke down preformed listeria monocytogenes biofilms

Listeria monocytogenes (L. monocytogenes) is the causal organism of the serious foodborne illness listeriosis and may grow as biofilms on food and food-processing equipments that protect them against environmental stress22. Streptomycin alone had a mild effect on biomass of L. monocytogenes biofilms after 6, 12, or 24 h treatment (Figure 1B). A combination of streptomycin and chitosan didn't not improve streptomycin-induced reduction of biofilm mass dramatically (Figure 1B), although it promoted killing of L. monocytogenes L. monocytogenes after a prolonged exposure (12 or 24 h) (Figure 1C). However, the C − S conjugate reduced both biofilm mass and viable cell countsafter 6, 12, or 24 h treatment. The biofilm mass after treatment with the C − S conjugate was below that at the starting point, indicating that the C − S conjugate was able to disperse the existing biofilms.

Concentration-dependent analysis further confirms that the C − S conjugate at various concentrations (0.125, 0.25, 0.5 mg/mL) was more efficient in disruption of L. monocytogenes biofilms than the respective mixture did after 24 h treatment (Figure S2). Visualization of L. monocytogenes biofilms with scanning electron microscopy (Figure 1D) and fluorescence microscopy (Figure 1E) showed a wide spectrum of morphological differences in biofilm architectures. Notably, very few scattered cell aggregates were observed in the biofilms after 24 h exposure to the C − S conjugate and there were less viable cells in the aggregates (Figures 1D and 1E).

The anti-biofilm efficacy of C − S conjugates was restricted to Gram-positive organisms

To see whether the C − S conjugate was able to smash up bacterial biofilms built by other organisms, initially two other Listeria species, Listeria innocua (Figure 2A) and Listeria welshimeri (Figure 2B) were tested. Quantification of biofilm biomass and cell viability demonstrated that the conjugate had a more pronounced effect than streptomycin or chitosan alone and the mixture did. These results rendered us to ask whether the conjugate was also effective in breaking down biofilms formed by other Gram-positive species such as Enterococcus faecalis23 and Staphylococcus aureus24, both of which can cause life-threatening infections in humans, especially in the nosocomial (hospital) environment. As expected, the C − S conjugate had stronger anti-biofilm and bactericidal activities towards Enterococcus faecalis (Figures 2C) and Staphylococcus aureus (Figures 2D) than the mixture did. Also, images from scanning electron microscopy (Figure 2E) and fluorescence microscopy (Figure 2F) evidenced that the architecture of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms exposed to the C − S conjugate displayed very few scattered cell aggregates, in which there were much less viable cells than that of the mixture.

C − S conjugate was also effective against preformed biofilms built by other Gram-positive organisms.

Biofilms formed by Listeria innocua (A), Listeria welshimeri (B), Enterococcus faecalis (C) or Staphylococcus aureus (D) were exposed to 0.25 mg/mL C − S conjugate (23% streptomycin, ~13 kDa chitosan), equivalent chitosan (C) or streptomycin (S) alone and the respective mixture (C + S) for 24 h. Biofilms incubated in TSB containing phosphate-buffered saline were used as control. Biofilm mass and viable cells were quantified. Staphylococcus aureus biofilm architectures after 24 h treatment were further examined by scanning electron microscopy (E) and fluorescence microscopy (F). These experiments were performed twice with similar results each time. Error bars represent SD.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative opportunistic human pathogen, which is generally employed as a model organism for investigation of biofilms25. Streptomycin alone resulted in a decrease of biofilm biomass and viable cell counts (Figure S3A). Streptomycin in concert with chitosan didn't further reduce biofilm mass, but killed more Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Differently, biofilm mass and cell viability of Pseudomonas aeruginosa remained unchanged after 24 h exposure to the C − S conjugate (Figure S3A). The similar findings (Figure S3B) were also observed in case of Salmonella typhimurium, another Gram-negative bacterium which is a rod-shaped foodborne pathogen26. Overall, these results clearly indicated that the C − S conjugate had a potential to disrupt existing biofilms formed by Gram-positive, but not Gram-negative organisms.

Structural requisites for anti-biofilm capacity of C − S conjugates

To clarify the role of streptomycin contents in anti-biofilm capacity of C − S conjugates, various amounts of streptomycin [0.3%, 15%, 23%, 32% (w/w)] were coupled to chitosan with a molecular mass of ~13 kDa. It appeared that the C − S conjugate containing 0.3% (w/w) streptomycin was not sufficient for induction of higher anti-biofilm and bactericidal activities than the mixture did (Figure 3A). An increase in streptomycin contents significantly enhanced the anti-biofilm and bactericidal capacity of C − S conjugates. Particularly, the C − S conjugate containing 23% streptomycin displayed an optimal activity for biofilm disruption and cell killing towards L. monocytogenes.

Structure-activity relationships in anti-biofilm capacities of C − S conjugate.

(A–C) L. monocytogenes biofilms were exposed to the following conjugates (C − S) and the respective mixtures (C + S) at 0.25 mg/mL for 24 h. Biofilms incubated in TSB containing phosphate-buffered saline were used as control. Biofilm mass and viable cells were quantified. (A) ~13 k chitosan derived C − S conjugates containing 0.3%, 15%, 23% and 32% (w/w) streptomycin; (B) C − S conjugates which contain similar levels of streptomycin and were derived from chitosan with different molecular mass: ~3 k (streptomycin: 30%), ~13 k (streptomycin: 28%) and ~180 k Da (streptomycin: 30%); (C) C − S conjugates which contain similar levels of streptomycin and were derived from chitosan (~13 k Da) with different N-deacetylation degrees: 50% DD (streptomycin: 25%), 75% DD (streptomycin: 23%) and 88% DD (streptomycin: 26%); (D) L. monocytogenes biofilms were exposed to 0.25 mg/mL of L-S conjugate containing 42% streptomycin, equivalent epoly-L-lysine (L, 2 ~ 3 kDa) or streptomycin (S) alone and the respective mixture (L + S) for 24 h. These experiments were performed three times with similar results each time. Error bars represent SD.

It is generally accepted that the anti-biofilm activity of chitosan was largely dependent on microbial species12,27, concentrations28, molecular weights29 and N-deacetylation degrees17. To further optimize the anti-biofilm capacity of C − S conjugates, similar levels of streptomycin were conjugated to chitosans varied in molecular mass: ~3 k, ~13 k or ~180 k Da. All three C − S conjugates demonstrated higher anti-biofilm and bactericidal activities towards L. monocytogenes than the respective mixtures did (Figure 3B). In particular, the C − S conjugate derived from ~13 k chitosan exhibited a greatest capacity in both disruption of L. monocytogenes biofilms and killing of live cells.

We further conjugated streptomycin to chitosans with different N-deacetylation degrees (DD: 50%, 75%, 88%) to verify impact of positive charges on the anti-biofilm capacity. All three C − S conjugates carrying similar amounts of streptomycin [23–26% (w/w)] could cause a reduction of biofilm mass and viable cell counts, compared with that of the vehicle control (Figure 3C). Along with the increase of N-deacetylation degrees in C − S conjugates, both anti-biofilm and bactericidal capacities enhanced. This raised the question whether conjugates derived from other antibacterial polycationic biopolymers such as poly-L-lysine30, instead of chitosan, also worked in a similar fashion. Results showed that the conjugate of poly-L-lysine and streptomycin indeed had stronger anti-biofilm and bactericidal activities than the respective mixture did (Figure 3D). Taken together, these findings suggested that polycationic properties enabled biopolymer-antibiotic conjugates to remain high anti-biofilm and bactericidal capacities.

Mechanistic insights into the anti-biofilm capability of C − S conjugates

Several factors accounted for the extraordinary resistance of biofilm bacteria to antibiotics31. One factor that is generally conceded to play a role in antibiotic resistance is the inability of the antibiotic to penetrate into biofilms, thereby reducing antibiotic available to interact with biofilm bacteria. Given chitosan has been shown to penetrate and damage biofilms12,13,17,18,32, we attempted to see whether chitosan conjugation facilitated streptomycin entry into biofilms.

Using a polyclonal antibody to streptomycin produced in rabbit and a second Dylight 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG, streptomycin residing in established biofilms was visualized. L. monocytogenes or P. aeruginosa biofilms exposed to streptomycin alone exhibited a weak green fluorescence (Figure 4). In contrast, the intense green fluorescence was observed in biofilms built by two organisms after treated with the mixture. L. monocytogenes biofilms exposed to the C − S conjugate elicited more brilliant green fluorescence than the mixture did. Differently, no green fluorescence was detected in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms exposed to the C − S conjugate. These findings implied that chitosan conjugation facilitated streptomycin access into biofilms built by certain organisms such as L. monocytogenes.

C − S conjugate facilitated antibiotic access to certain biofilm bacteria.

L. monocytogenes (A) or Pseudomonas aeruginosa (B) biofilms were exposed to 0.25 mg/mL C − S conjugate (23% streptomycin, ~13 kDa chitosan), equivalent chitosan (C) or streptomycin (S) alone and the respective mixture (C + S) for 1 h. Biofilms incubated in TSB containing phosphate-buffered saline were used as control. Streptomycin residing in biofilms is examined by Immunofluorescence. Immunoreactivity was quantified by using Image Pro Plus. These experiments were performed twice with similar results each time. Magnifications: ×1000. Error bars represent SD.

C − S conjugates prevent bacterial biofilm formation

L. monocytogenes biofilm formation was examined in the presence of individual agents, the mixture or C − S conjugate for 6, 12 or 24 h. An exposure to streptomycin or chitosan alone for 6 h prevented planktonic cells from biofilm formation (Figure 5A), but didn't affect the cell viability as compared with the vehicle control (Figure 5B). A prolonged (12 or 24 h) treatment with individual agents resulted in a decrease of both biofilm mass and cell viability. The combination of streptomycin and chitosan suppressed both biofilm formation and cell viability in a more remarkable manner whereas the C − S conjugate facilitated this suppression (Figures 5A and 5B).

C − S conjugate inhibited bacterial biofilm formation.

The following bacteria were seeded in 96-well plates in the presence of 0.25 mg/mL C − S conjugate (23% streptomycin, ~13 kDa chitosan), equivalent chitosan (C) or streptomycin (S) alone and the respective mixture (C + S) for hours indicated. Biofilms incubated in TSB containing phosphate-buffered saline were used as control. (A and B) L. monocytogenes (6, 12, 24 h); (D) Listeria innocua (24 h); (E) Listeria welshimeri (24 h); (F) Staphyloccocus aureus (24 h). Biofilm mass and viable cells were quantified and L. monocytogenes biofilm architectures after 24 h treatment were further examined by scanning electron microscopy (C). These experiments were performed 3 times with similar results each time. Error bars represent SD.

Again, the C − S conjugate exhibited a stronger inhibitory activity towards biofilm formation by two other listeria species, L. innocua (Figure 5D) and L. welshimeri (Figure 5E) than individual agents and the mixture did. The similar findings were also observed in case of Staphylococcus aureus by quantification of biofilm biomass and cell viability (Figure 5F). The biofilm architectures by microscopic examination further indicated that there were few viable cells in scattering patterns after 24 h exposure to the C − S conjugate (Figure 5C).

Discussion

Biofilms are considered as an universal survival lifestyle for microbes to protect themselves from antimicrobial attack3. Susceptibility tests with in vitro biofilm models have demonstrated biofilm bacteria survive after treatment with antibiotics at hundreds or even a thousand times of the minimum inhibitory concentration of planktonic cells33. The aim of this study was to test whether chitosan conjugation improved the effectiveness of an antibiotic, streptomycin against bacterial biofilms.

Our data showed that the C − S conjugate was more effective in eradiation of established biofilms and killings of biofilm bacteria than streptomycin alone or their mixture did (Figures 1–2). This was the case for biofilms built by all Gram-positive organisms tested, but not Gram-negative organisms such as P. aeruginosa and S. typhimurium. These observations raised the question whether the C − S conjugate had a priority in killings of Gram-positive organisms, when compared with the mixture of streptomycin and chitosan. In fact, the bactericidal activity of the C − S conjugate wasn't dissimilar to that of the mixture towards Gram-positive or –negative bacteria, according to the minimum inhibitory concentration of planktonic cells (Table S1).

Immunofluorescence analysis of streptomycin levels residing in established biofilms suggested that chitosan conjugation made more streptomycin access into biofilms built by L. monocytogenes, but not P. aeruginosa (Figure 4). This observation was in agreement with the earlier data that the C − S conjugate was effective to remove biofilms built by Gram-positive (Figure 1–2), but not Gram-negative organisms (Figure S3). This data implied that the specificity of the C − S conjugate against biofilms built by Gram-negative organisms was related to their inherent biofilm architectures.

In summary, our data highlighted that the polycationic property enabled chitosan as an efficient Trojan horse to deliver streptomycin into biofilms built by Gram-positive organisms. This made bacterial biofilms more susceptible to streptomycin at a lowest effective dose. Given chitosan has received considerable attention as a biomaterial, due to its good biocompatibility and low toxicity (especially for chitosan with a DD higher than 35%)34, this novel strategy might open up a new avenue to overcome the inherent resistance of biofilms to antibiotics such as streptomycin and come into wide use for combating biofilms in industrial and medical area.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

L. monocytogenes (CMCC 54004), Staphyloccocus aureus (ATCC 29213), Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PAO1) and Salmonella typhimurium (SL1344) were generous gifts from received from Prof. Xia (Colloge of Food Science and Engineering, Northwest A&F University). Listeria welshimeri (GIM1.232) and Listeria innocua (GIM1.365) were purchased from Microbial Culture Collection Center of Guangdong Institute of Microbiology (GIMCC). The strains were cultured in Tryptone Soya broth (TSB) at 37°C and the grown culture was used for inoculation into the wells of plastic microtiter plate (Corning, NY) for subsequent quantification of biofilm production.

Synthesis of biopolymer-streptomycin conjugates

A solution of streptomycin sulfate and NaCNBH3 was added into chitosan or poly-L-lysine aqueous solutions20. The reaction mixture was stirred for 15 h in the dark and then dialyzed 2 days and finally lyophilized. Streptomycin contents in conjugates were determined through quantification of guanidyl groups21 and streptomycin sulfate was used as a standard. For 1H NMR spectral analysis, samples were dissolved in D2O (10 mg/mL) and the spectra were carried out on a Bruker AV500 MHz (Bruker, Switzerland).

Biofilm formation

One hundred microlitres, approximately 107 cfu of each bacterial solution were added to individual wells of a sterile flat-bottomed 96-well polystyrene microtitre plates (Corning, NY). The microtitre plates were covered and incubated at 37°C for 24 h to allow cell attachment and biofilm formation. Then, the supernatant containing non-adhered cells was removed and washed three times using 100 μL 0.9% (w/v) NaCl. Existing biofilms were incubated at 37°C in TSB supplemented with compounds for different periods as indicated and each treatment includes 6 wells and biofilms incubated in TSB containing PBS was used as control. Biofilm mass were evaluated by crystal violet assay35. To count biofilm bacteria,0.1% Triton X-100 was added into each well and sonicated for 5 min and serial dilutions from each well are plated for enumeration. All assays were performed 3 times with similar results.

Biofilm inhibition assay

Instead of pre-incubation for 24 h at 37°C, one hundred microlitres of L. monocytogenes in TSB (approximately 107 cfu) were seeded into individual wells of microtiter plates in the presence of compounds for different periods as indicated. Biofilm mass and bacterial counts were evaluated as describe above.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

A modified SEM method was used to analyze the biofilm morphology36. Test samples were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4°C for 24 h. Cells were rinsed with 0.1 M PBS three times for 10 min at each interval. The cultures were then dehydrated in a gradient alcohol concentration (50%, 70%, 80%, 90% and 100%) for 10 min at each concentration. The specimen was left in 100% alcohol to prevent it from drying and mounted onto an aluminum stub with carbon tape, sputter- coated with gold a before examination.

Fluorescence microscopy

Bacteria were grown on glass coverslips submerged with 1 ml of TSB in 24-well plates at 37°C for 24 h to allow biofilm formation. Then, the supernatant containing non-adhered cells was removed and washed. Existing biofilms were incubated at 37°C in TSB supplemented with compounds for 24 h as indicated. Biofilms were fixed using a 5% paraformaldehyde solution for 30 min at room temperature. After washed with 2 ml PBS, 5-(4, 6-dichlorotriazinyl) aminofluorescein (5-DTAF) was added and incubated with shaking for 2 h at room temperature. The slides were washed 3 times in PBS and inverted onto a cover glass. Biofilms were imaged through the following excitation and emission wavelengths: 488 nm excitation and 505 to 530 nm emission detection range for 5-DTAF.

Immunofluorescence

As above, biofilms on glass coverslips were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. After treatment with 0.25% Triton X-100 and blocking with 1% BSA in PBS, coverslips were incubated with a polyclonal antibody for streptomycin (rabbit anti-streptomyicn ployclone. Abcam) at 4°C overnight and then incubated with a second Dylight 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc). Immunoreactivity was quantified by using Image Pro Plus (version 5.0, Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD).

MIC assay

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of compounds against planktonic bacteria was performed using microdilution assay. C − S conjugate (23% streptomycin, ~13 kDa chitosan), equivalent chitosan (C) or streptomycin (S) alone and the respective mixture (C + S) were dissolved in TSB broth at an initial concentration of 1024 μg/mL and then serially diluted. The bacteria with a final concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/mL in TSB broth per well were inoculated at 37°C for 24 h.

Statistical analysis

All graphical evaluations were made using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate significant differences.

References

Mittelman, M. W. Structure and functional characteristics of bacterial biofilms in fluid processing operations. J Dairy Sci 81, 2760–2764 (1998).

Van Houdt, R. & Michiels, C. W. Biofilm formation and the food industry, a focus on the bacterial outer surface. J Appl Microbiol 109, 1117–1131 (2010).

Flemming, H. C. & Wingender, J. The biofilm matrix. Nat Rev Microbiol 8, 623–633 (2010).

Costerton, J. W., Stewart, P. S. & Greenberg, E. P. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284, 1318–1322 (1999).

Hall-Stoodley, L. & Stoodley, P. Biofilm formation and dispersal and the transmission of human pathogens. Trends Microbiol 13, 7–10 (2005).

Taraszkiewicz, A., Fila, G., Grinholc, M. & Nakonieczna, J. Innovative Strategies to Overcome Biofilm Resistance. BioMed Research International 2013, (2012).

Lewis, K. Riddle of biofilm resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45, 999–1007 (2001).

Lu, T. K. & Collins, J. J. Dispersing biofilms with engineered enzymatic bacteriophage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 11197–11202 (2007).

Molobela, I. P., Cloete, T. E. & Beukes, M. Protease and amylase enzymes for biofilm removal and degradation of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens bacteria. PhD. Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa (2010).

Allaker, R. The use of nanoparticles to control oral biofilm formation. J Dent Res 89, 1175–1186 (2010).

Adonizio, A., Kong, K.-F. & Mathee, K. Inhibition of quorum sensing-controlled virulence factor production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by South Florida plant extracts. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52, 198–203 (2008).

Orgaz, B., Lobete, M. M., Puga, C. H. & Jose, C. S. Effectiveness of Chitosan against Mature Biofilms Formed by Food Related Bacteria. Int J Mol Sci 12, 817–828 (2011).

Martinez, L. R. et al. The use of chitosan to damage Cryptococcus neoformans biofilms. Biomaterials 31, 669–679 (2010).

Lim, S.-H. & Hudson, S. M. Review of chitosan and its derivatives as antimicrobial agents and their uses as textile chemicals. J Macromol Sci, Part C: Polymer Reviews 43, 223–269 (2003).

Huang, M., Khor, E. & Lim, L.-Y. Uptake and cytotoxicity of chitosan molecules and nanoparticles: effects of molecular weight and degree of deacetylation. Pharm Research 21, 344–353 (2004).

Cobrado, L. et al. Cerium, chitosan and hamamelitannin as novel biofilm inhibitors? J Antimicrob Chemother 67, 1159–1162 (2012).

Rabea, E. I., Badawy, M. E., Stevens, C. V., Smagghe, G. & Steurbaut, W. Chitosan as antimicrobial agent: applications and mode of action. Biomacromolecules 4, 1457–1465 (2003).

Carlson, R. P., Taffs, R., Davison, W. M. & Stewart, P. S. Anti-biofilm properties of chitosan-coated surfaces. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 19, 1035–1046 (2008).

Sharma, D., Cukras, A. R., Rogers, E. J., Southworth, D. R. & Green, R. Mutational analysis of S12 protein and implications for the accuracy of decoding by the ribosome. J Mol Biol 374, 1065–1076 (2007).

Yalpani, M. & Hall, L. D. Some chemical and analytical aspects of polysaccharide modifications. III. Formation of branched-chain, soluble chitosan derivatives. Macromolecules 17, 272–281 (1984).

Pretorius, D., Van Staden, J. & Botha, A. An automated colorimetric method for the determination of cyanoguanidine in water. Water SA WASADV 17, 273–280 (1991).

Møretrø, T. & Langsrud, S. Listeria monocytogenes: biofilm formation and persistence in food-processing environments. Biofilms 1, 107–121 (2004).

Kuch, A. et al. Insight into antimicrobial susceptibility and population structure of contemporary human Enterococcus faecalis isolates from Europe. J Antimicrob Chemother 67, 551–558 (2012).

Fitzgerald, S. F. et al. A 12-year review of Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections in haemodialysis patients: more work to be done. J Hosp Infect 79, 218–221 (2011).

Ma, L. et al. Assembly and development of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix. PLoS Pathog 5, e1000354 (2009).

Stewart, M. K., Cummings, L. A., Johnson, M. L., Berezow, A. B. & Cookson, B. T. Regulation of phenotypic heterogeneity permits Salmonella evasion of the host caspase-1 inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 20742–20747 (2011).

Costa, E. M., Silva, S., Tavaria, F. K. & Pintado, M. M. Study of the effects of chitosan upon Streptococcus mutans adherence and biofilm formation. Anaerobe 20, 27–31 (2013).

Pasquantonio, G. et al. Antibacterial activity and anti-biofilm effect of chitosan against strains of Streptococcus mutans isolated in dental plaque. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 21, 993–997 (2008).

Chavez de Paz, L. E., Resin, A., Howard, K. A., Sutherland, D. S. & Wejse, P. L. Antimicrobial effect of chitosan nanoparticles on streptococcus mutans biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol 77, 3892–3895 (2011).

Shima, S., Matsuoka, H., Iwamoto, T. & Sakai, H. Antimicrobial action of epsilon-poly-L-lysine. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 37, 1449–1455 (1984).

Davies, D. Understanding biofilm resistance to antibacterial agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2, 114–122 (2003).

Martinez, L. R. et al. Demonstration of antibiofilm and antifungal efficacy of chitosan against candidal biofilms, using an in vivo central venous catheter model. J Infect Dis 201, 1436–1440 (2010).

Ceri, H. et al. The Calgary Biofilm Device: new technology for rapid determination of antibiotic susceptibilities of bacterial biofilms. J Clin Microbiol 37, 1771–1776 (1999).

Hirano, S., Seino, H., Akiyama, Y. & Nonaka, I. Chitosan: a biocompatible material for oral and intravenous administrations. in Progress in biomedical polymers 283–290 (Springer, 1990).

Djordjevic, D., Wiedmann, M. & McLandsborough, L. A. Microtiter Plate Assay for Assessment of Listeria monocytogenes Biofilm Formation. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 68, 2950–2958 (2002).

Kim, J. E., Choi, N. H. & Kang, S. C. Anti-listerial properties of garlic shoot juice at growth and morphology of Listeria monocytogenes. Food Control 18, 1198–1203 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by special talent recruitment fund of Northwest A&F University and in part by the “Interdisciplinary Cooperation Team” Program for Science and Technology Innovation of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.Z., H.M. and J.D. designed research and contributed new reagents/analytic tools; A.Z. and H.M. performed research; W.Z. and G.C. performed statistical analysis; A.Z. and J.D. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary figure legends

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, A., Mu, H., Zhang, W. et al. Chitosan Coupling Makes Microbial Biofilms Susceptible to Antibiotics. Sci Rep 3, 3364 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03364

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03364

This article is cited by

-

Effective Release of Ciprofloxacin and Rifampicin Antibiotics from Alginate-Chitosan Complex and Its Application Against Clinical Strains of Staphylococcus aureus

BioNanoScience (2023)

-

Chitosan Schiff bases/AgNPs: synthesis, characterization, antibiofilm and preliminary anti-schistosomal activity studies

Polymer Bulletin (2022)

-

State-of-the-art polymeric nanoparticles as promising therapeutic tools against human bacterial infections

Journal of Nanobiotechnology (2020)

-

Alternative strategies for the application of aminoglycoside antibiotics against the biofilm-forming human pathogenic bacteria

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2020)

-

Exploring the Therapeutic Efficacy of Zingerone Nanoparticles in Treating Biofilm-Associated Pyelonephritis Caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the Murine Model

Inflammation (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.