Abstract

We have successfully designed the geometry of the microwave cavity and the thin metal electrode, achieving resonance of the microwave cavity with the metal-insulator-semiconductor (MIS) device structure. This very simple MIS device operates in the cavity, where charge carriers are injected quantitatively by an applied bias at the insulator-semiconductor interface. The local motion of the charge carriers was clearly probed through the applied external microwave field, also giving the quantitative responses to the injected charge carrier density and charge/discharge characteristics. By means of the present measurement system named field-induced time-resolved microwave conductivity (FI-TRMC), the pentacene thin film in the MIS device allowed the evaluation of the hole and electron mobility at the insulator-semiconductor interface of 6.3 and 0.34 cm2 V−1 s−1, respectively. This is the first report on the direct, intrinsic, non-contact measurement of charge carrier mobility at interfaces that has been fully experimentally verified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interfaces play an important role in organic electronics from both a structural and functional point of view. For example, material/substrate and material/air interfaces are known to cause molecules to adopt different orientations from those inside the bulk material1,2,3,4. Interfaces between p- and n-type semiconductors have a strong influence on the photovoltaic response5,6,7. In most electronic devices, charge carriers are injected or extracted through metal/semiconductor interfaces during device operation. In particular, organic field-effect transistors (OFETs)8,9,10, one of the most practical device applications of organic semiconductors, rely highly on interfacial phenomena because even charge-carrier transport takes place at insulator/semiconductor interfaces rather than in the bulk. In fact, the hole and electron mobility in OFETs was found to be extremely sensitive to the microscopic morphology of the films at the interfaces11,12. Although improvement of OFET performance is awaited, tools for analyzing interfacial carrier transport are still undeveloped. Limited examples include the quantification of electronic energy levels of molecules at material surfaces or interfaces by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) or ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) measurements. Another unique approach was reported by Marumoto and co-workers, who used field-induced electron spin resonance (FI-ESR) to evaluate the spin density distribution of charge carriers at pentacene–SiO2 interfaces13,14. Other studies focused on charge-carrier motion at interfaces and used organic insulators such as poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS), poly(methylmethacrylate) (PMMA) and self-assembled monolayers (SAM) to control the interfacial morphology15,16,17. Building on this background, we report a novel technique named field-induced time-resolved microwave conductivity (FI-TRMC) for evaluating charge carrier mobility at the interface between insulators and semiconductors without grain boundary effects (Fig. 1). This newly-developed measurement system involves charge carrier generation at insulator-semiconductor interfaces by applying a gate bias and evaluation of carrier mobilities through microwave probing, which potentially clarifies the effect of insulators on the intrinsic mobility of charge carriers in OFETs.

Microwave-based techniques have been recently developed as noncontact evaluation methods to evaluate intrinsic charge carrier mobilities. In a pioneering work, Warman and co-workers reported the pulse radiolysis time-resolved microwave conductivity (PR-TRMC) technique, where radiation-induced charge carriers are made to resonate using a microwave field. Using this method, we evaluated nm-scale motion of charge carriers, obtaining the sum of the local-scale mobility Σμ ( = μhole + μelectron)18,19. After that, several researchers including us developed the flash photolysis time-resolved microwave conductivity (FP-TRMC) technique, where charge carriers are generated by photoinduced charge-separation processes20,21,22,23,24. Use of photoexcitation process allowed us to cover larger variety of materials and to determine their carrier mobility using quite a small amount of samples. However, because of the radiation or photoexcitation induced ionization mechanisms involved, both holes and electrons are generated together, which makes it difficult to differentiate the contributions from the individual hole and electron mobilities. For that reason, the FI-TRMC system is noteworthy, since the system clarifies the contribution of hole or electron conduction at the interfaces by applying a positive or negative bias selectively.

Results

Experimental setup

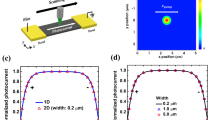

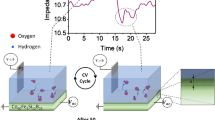

For the first demonstration of FI-TRMC, we prepared a metal-insulator-semiconductor (MIS) device adopting a Au/SiO2/PMMA/pentacene/Au configuration (Fig. 2). We used pentacene as a representative organic semiconductor with high hole mobility25,26, while PMMA was selected as an insulator. Two gold electrodes working as a gate enable control of the density and polarity of the accumulated charge carriers at the interfaces by applying a gate bias voltage, which leads to the direct quantification of the charge carrier numbers. Equation (1) shows the relationship between the change in charge carrier number (ΔN) and the change in the applied gate bias voltage (ΔV).

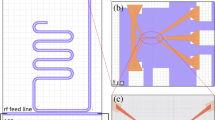

where C and e show the capacitance and the elementary charge of an electron, respectively. The value of N was determined by a Wayne Kerr Precision Component Analyzer 6430B capacitive sensor. Through atomic force microscopy (AFM), the vapor-deposited pentacene film in the MIS device (Fig. 2d) was characterized as having a typical polycrystalline morphology (Supplementary Fig. S1). In addition, an FET-type device with a configuration analogous to the MIS device (Fig. S2) exhibited typical FET characteristics (Fig. S3). These observations indicated that the MIS device is appropriately designed for FI-TRMC measurements. Fig. 3 shows a schematic illustration of a microwave circuit for FI-TRMC using X-band microwave radiation (~9 GHz). In FI-TRMC measurements, the microwave frequency and power are adjusted by a Rohde Schwarz SMF 100 A Signal Generator at ~ 9.0 GHz and 0.9–1.0 mW, respectively. The motion of charge carriers accumulated at the interfaces is modulated by the low electric field associated with the microwaves. Holes or electrons are directly injected by application of a microsecond-pulse bias voltage from a Wave Factory Multifunction Generator WF 1973, promoting field-induced charge-carrier generation at the pentacene–PMMA interface. The FI-TRMC signals picked up by a diode (rise time < 1 ns) were monitored by a Tektronix TDS5054 Digital Phosphor Oscilloscope. All the experiments were carried out under ambient atmosphere at room temperature.

Principle of FI-TRMC method

When the MIS device is set in the microwave cavity (Fig. S4.) and a gate bias is applied, charge carriers are generated at the semiconductor/insulator interface. These carriers resonate as they absorb the incident microwaves which results in a change in the power of the reflected microwaves ΔPr. The relation between the change in the conductivity Δσ (S cm−1) and the relative change in the reflected microwave power ΔPr/Pr is shown in equation (2)27. Equation (3) describes the relation between the change in the value of the electrical conductivity Δσ caused by the applied gate bias and the change in the number of charge carriers ΔN that have accumulated in the MIS device due to the gate bias voltage.

Here, K and μ denote an experimental parameter and the charge carrier mobility, respectively. In order to express the change in the reflected microwave power ΔPr (W) in terms of ΔNμ (cm2 V s), it is necessary to determine the quantitative relation between ΔNμ and ΔPr.

Correlation equation

Prior to the measurement of the pentacene/PMMA MIS device, we investigated the relation between ΔNμ and ΔPr by loading standard samples into the microwave cavity. Gold (σ = 4.52 × 105 S cm−1), manganese (σ = 6.94 × 103 S cm−1) and p-doped silicon (σ = 10 S cm−1) were selected as the standard samples28. They were vapor deposited as thin films onto quartz substrates with their thicknesses controlled, so that the total deposited mass was known. The mass of these samples was then converted into the value of ΔNμ using

where m (g) and d (g/cm3) denote the mass and density of the standard samples, respectively. The value of ΔNμ can be regarded as the change in the pseudo electrical conductivity. By measuring the value of ΔPr for each standard sample, we obtained the relation between ΔNμ and ΔPr shown in Fig. 4. Two straight lines with different slopes were used to fit the data in the lower ΔNμ (1015–1017) and higher ΔNμ regions (over 1018). For lower ΔNμ, the value of ΔPr becomes small (i.e.: the change in the Q value is small), since ΔPr is proportional to the electrical conductivity change (Δσ)29,30. Thus, ΔPr is proportional to the pseudo electrical conductivity ΔNμ and the data in the low ΔNμ region (for Mn and p-doped Si) can be successfully fitted using the equation:

On the other hand, equation (5) does not provide a good fit to the data in the high ΔNμ region (for Au). When samples with high electrical conductivity such as Au are used, the microwave amplitude decreases significantly at the surface of the thin film due to skin-depth effects. In such cases where the interaction of microwaves with a material is confined to the near-surface region, it is necessary to use the skin-depth approximation31:

where Δω represents the difference in the resonance frequency between a cavity with and without a sample present and ω0, C, G, Zs and μ0 are the resonance angular frequency, the metallic shift associated with a perfect conductor, a resonator constant, the surface impedance and the permeability, respectively. The Q value, representing the microwave power loss in the cavity, can be divided into Qu, Qc and Qs components associated with microwave interaction with the inner walls of the cavity, the coupling between the cavity and the waveguide and the sample, respectively29. The Qu and Qc components are constant during the measurement of microwave power loss, so these can be included in Q1. The relation between Q1, Qs and Q can be expressed as:

The relation between Qs, ω0 and the resonance frequency of the empty cavity f0 ( = ω0/2π) is expressed by31:

Microwaves passing through the sample give rise to a decrease in the electric field and a phase shift, as indicated by equation (9) and this causes a change in the Q value and resonant frequency. The intensity of the microwaves reflected from the cavity is expressed by equation (10):

The value of ΔPr/Pr is defined by the complex conjugation of the reflectance:

In the case of Δω/ω0 ~ 0, equation (11) can be approximated by a linear function of (1/Qs).

Then, substituting equations (6), (7) and (9) into equation (12) results in:

Remarkably, ΔPr is proportional to (σ1)1/2. Therefore, the data for Au can be fitted using the following equation:

The values of N and μ for common organic semiconductors are smaller than those for Au, Mn and Si. In fact, the value of N in MIS devices is known to be around 1012–1013 through calculation of their capacitance. Since the charge-carrier mobility for organic semiconductors is lower than 10 cm2 V−1 s−1, the value of ΔNμ is 1014 at most, which allows us to conclude that the linear approximation shown in equation (5) sufficiently describes the relation between ΔPr and ΔNμ.

FI-TRMC demonstration

When a gate bias of –40 V was applied, the pentacene/PMMA MIS device displayed a time-dependent microwave power change (ΔPr) with saturated behavior (Fig. 5a), where the bias voltage was applied between 9 to 39 ms. At the same time, the charging-discharging current appeared to respond to the applied gate bias (Fig. 5a). The differential of ΔPr was in good agreement with the current signal, which indicates that the ΔPr response is associated clearly with charges accumulated in the MIS device. The ΔPr response resembles the voltage response characteristics of a capacitor in a typical resistor–capacitor (RC) circuit and in the decay region (39–50 ms) gives the linear plots shown in Fig. S5. Fig. 5b. shows the dependence of ΔPr on the applied gate bias. When the applied gate bias voltage was decreased from 0 V to –60 V, ΔPr increased proportionally, probably because the number of accumulated holes became large in relation to the absolute value of the gate bias. In sharp contrast, the response of ΔPr to the positive gate bias was poor from 0 V to 60 V (Fig. 5c), suggesting a lower conductivity for electrons in the MIS device. After measuring ΔPr at each gate bias and capacitance and using equations (5) and (1), we can draw the ΔN–ΔNμ plots, as shown in Fig. 6. The slope ( = δNμ/δN) corresponds to the value of the charge carrier mobility, providing the approximate values μhole = 6.3 cm2 V−1 s−1 and μelectron = 0.34 cm2 V−1 s−1 for the pentacene MIS device.

Discussion

There are many reports on FET hole mobilities of over 1 cm2 V−1 s−1 in single pentacene crystals32,33, where the value is considered to be the boundary between hopping and band conduction mechanisms for charge carrier transport34,35,36. Considering the nanometer-scale spatial motion of charge carriers in the FI-TRMC measurement, the range of motion of holes is assumed to be within a single domain. Therefore, the high hole mobility of 6.3 cm2 V−1 s−1 suggests that the transport mechanism for holes involves band conduction within a domain. It should also be noted that precise evaluation of hole mobility in pentacene by the FP-TRMC method has been limited so far, due to the lack of photo-induced charge carriers37. In that sense, the present work provides the first evaluation of intrinsic hole mobility in pentacene materials. Meanwhile, there have been no reports on the electron transport properties of pentacene thin films detected directly in air. The reason for electron transport occurring in air, as observed in the present work, is most likely due to the local motion of electrons. This in turn means electrons can avoid traps such as oxygen molecules, impurities and crystal grain boundaries in a pentacene thin solid film, also suggesting that such traps dramatically inhibit the long translational motion of electrons.

Overall, we successfully developed the FI-TRMC measurement system for evaluating charge carrier mobility including the effect of the interfaces and minimizing the effect of grain boundaries. Considering nanometer-scale charge carrier motion and a hole mobility as high as 6.3 cm2 V−1 s−1, we clarified that hole transport occurs via a band conduction mechanism within individual pentacene domains. The value of hole mobility measured by FI-TRMC is as high as the FET hole mobility in a single pentacene crystal32,33, which potentially allows us to determine the charge carrier mobility in single crystalline states even using polycrystalline materials. Considering the above achievements, we believe that FI-TRMC, the newly-developed measurement system demonstrated here, serves as not only an potential evaluation system for FET mobilities in thin-film materials, but also a powerful tool for investigating the effect of insulating materials on the charge carrier mobility.

Methods

Device fabrication

Pentacene and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) were purchased from Aldrich. The quartz substrate (4.9 mm × 50 mm) was treated by UV–O3 prior to use. For fabrication of the gate electrode, Ti (3 nm) and Au (30 nm) were deposited on the substrate through a shadow mask in a vacuum deposition system. The interaction between the probing microwave and ultra-thin metal electrodes is expressed by the skin depth (δ) equation:

where ω, μ0 and σm are the frequency of interacting microwave, magnetic permeability and conductivity in the metal electrode, respectively. The use of 10 GHz microwave and Au electrodes results in its value of δ as ~ 790 nm, suggesting the thin enough thickness of the metal electrodes (5 and 30 nm) to unveil the organic semiconductor layer from the metal electrode shielding. The area of the gate electrode was 3 mm × 6 mm. The substrate was then set in a vacuum deposition system equipped with a RF-sputtering gun under dry Ar gas at room temperature. The SiO2 gate insulator was deposited by RF-sputtering at 100 W onto the Au gate electrode through a shadow mask under an Ar gas flow at 1.1 Pa. The thickness was approximately 880 nm. A PMMA dielectric layer was spin-coated onto the substrate at 250 nm with 3 wt% PMMA in a toluene solution and annealed at 100°C under N2 gas. A pentacene organic semiconductor layer was deposited onto the substrate to 50 nm in thickness by vacuum deposition under 4–6 × 10−5 Pa. The rate of deposition was 0.3–0.5 Å per second. After the deposition of the pentacene, a 30 nm thick Au layer was deposited through a shadow mask to fabricate the source electrode.

References

Ma, H., Yip, H.-L., Huang, F. & Jen, A. K.-Y. Interface Engineering for Organic Electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 20, 1371–1388 (2010).

Chen, W., Qi, D.-C., Huang, H., Gao, X. & Wee, A. T. S. Organic–Organic Heterojunction Interfaces: Effect of Molecular Orientation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21, 410–424 (2010).

Peisert, H., Biswas, I., Knupfer, M. & Chassé, T. Orientation and electronic properties of phthalocyanines on polycrystalline substrates. Phys. Status Solidi B 246, 1529–1545 (2009).

Grelet, E. & Bock, H. Control of the orientation of thin open supported columnar liquid crystal films by the kinetics of growth. Europhys. Lett. 73, 712–718 (2006).

Baranovskii, S. D., Wiemer, M., Nenashev, A. V., Jansson, F. & Gebhard, F. Calculating the Efficiency of Exciton Dissociation at the Interface between a Conjugated Polymer and an Electron Acceptor. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 1214–1221 (2012).

Potscavage, W. J., Sharma, A. & Kippelen, B. Critical Interfaces in Organic Solar Cells and Their Influence on the Open-Circuit Voltage. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 1758–1767 (2009).

Armstrong, N. R. et al. Organic/Organic' Heterojunctions: Organic Light Emitting Diodes and Organic Photovoltaic Devices. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 30, 717–731 (2009).

Mei, J., Diao, Y., Appleton, A. L., Fang, L. & Bao, Z. Integrated Materials Design of Organic Semiconductors for Field- Effect Transistors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 6724–6746 (2013).

Klauk, H. Organic thin-film transistors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 2643–2666 (2010).

Benson, N., Melzer, C., Schmechel, R. & von Seggern, H. Electronic states at the dielectric/semiconductor interface in organic field effect transistors. Phys. Status Solidi A 205, 475–487 (2008).

Virkar, A. A., Mannsfeld, S., Bao, Z. & Stingelin, N. Organic Semiconductor Growth and Morphology Considerations for Organic Thin-Film Transistors. Adv. Mater. 22, 3857–3875 (2010).

Di, C.-A., Liu, Y., Yu, G. & Zhu, D. Interface Engineering: An Effective Approach toward High-Performance Organic Field-Effect Transistors. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 1573–1583 (2009).

Tanaka, H. et al. Electron spin resonance observation of charge carrier concentration in organic field-effect transistors during device operation. Phys. Rev. B 87, 045309 (2013).

Marumoto, K., Kuroda, S., Takenobu, T. & Iwasa, Y. Spatial Extent of Wave Functions of Gate-Induced Hole Carriers in Pentacene Field-Effect Devices as Investigated by Electron Spin Resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 256603 (2006).

Reese, C., Chung, W.-J., Ling, M.-M., Roberts, M. & Bao, Z. High-performance microscale single-crystal transistors by lithography on an elastomer dielectric. App. Phys. Lett. 89, 202108 (2006).

Takeya, J. et al. Very high-mobility organic single-crystal transistors with in-crystal conduction channels. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 102120 (2007).

Pernstich, K. P. et al. Threshold voltage shift in organic field effect transistors by dipole monolayers on the gate insulator. J. Appl. Phys. 96, 6431 (2004).

Warman, J. M. & de Haas, M. P. in Recent Trends in Radiation Chemistry (Eds. Wishart, J. F. & Rao, B. S. M.) World Scientific Publishing, Singapore, 2010, pp. 161.

Hoofman, R. J. O. M., de Haas, M. P., Siebbeles, L. D. A. & Warman, J. M. Highly mobile electrons and holes on isolated chains of the semiconducting polymer poly(phenylene vinylene). Nature 392, 54–56 (1998).

Piris, J. et al. Aligned thin films of discotic hexabenzocoronenes: Anisotropy in the optical and charge transport properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 14, 1053–1061 (2004).

Dicker, G., de Haas, M. P., Siebbeles, L. D. A. & Warman, J. M. Electrodeless time-resolved microwave conductivity study of charge-carrier photogeneration in regioregular poly(3-hexylthiophene) thin films. Phys. Rev. B 70, 045203 (2004).

Saeki, A., Koizumi, Y., Aida, T. & Seki, S. Comprehensive Approach to Intrinsic Charge Carrier Mobility in Conjugated Organic Molecules, Macromolecules and Supramolecular Architectures. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 1193–1202 (2012).

Saeki, A., Seki, S., Sunagawa, T., Ushida, K. & Tagawa, S. Charge-carrier dynamics in polythiophene films studied by in-situ measurement of flash-photolysis time-resolved microwave conductivity (FP-TRMC) and transient optical spectroscopy (TOS). Philos. Mag. 86, 1261–1276 (2006).

Acharya, A., Seki, S., Saeki, A., Koizumi, Y. & Tagawa, S. Study of transport properties in fullerene-doped polysilane films using flash photolysis time-resolved microwave technique. Chem. Phys. Lett. 404, 356–360 (2005).

Butko, V. Y., Chi, X., Lang, D. V. & Ramirez, A. P. Field-effect transistor on pentacene single crystal. Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 4773–4775 (2003).

Anthony, J. E. The Larger Acenes: Versatile Organic Semiconductors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 452–483 (2008).

Infelta, P. P., de Hass, M. P. & Warman, J. M. The study of the transient conductivity of pulse irradiated dielectric liquids on a nanosecond timescale using microwaves. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 10, 353–365 (1997).

Electrical Resistivity of Pure Materials. In: HANDBOOK of CHEMISTRY and PHYSICS, 81st, Lied, David, R. CRC, 2000–2001. Section 12.

Slater, J. C. Microwave Electronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 18, 441–512 (1946).

Shimamori, H. & Hotta, H. The Pulse Radiolysis-Microwave Method. in Proceedings of research activity at Fukui Institute of Technology 11, 103 (1981).

Maeda, A., Kitano, H. & Inoue, R. Microwave conductivities of high-Tc oxide superconductors and related materials. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 17, R143–R185 (2005).

Jurchescu, O. D., Popinciuc, M., van Wees, B. J. & Palstra, T. T. M. Interface-Controlled, High-Mobility Organic Transistors. Adv. Mater. 19, 688–692 (2007).

Goldmann, C. et al. Hole mobility in organic single crystals measured by a “flip-crystal” field-effect technique. J. Appl. Phys. 96, 2080–2086 (2004).

Jurchescu, O. D., Baas, J. & Palstra, T. T. M. Effect of impurities on the mobility of single crystal pentacene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 3061–3063 (2004).

Aleshin, A. N., Lee, J. Y., Chu, S. W., Kim, J. S. & Park, Y. W. Mobility studies of field-effect transistor structures based on anthracene single crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 5383–5385 (2004).

Liu, C. et al. Solution-Processable Organic Single Crystals with Bandlike Transport in Field-Effect Transistors. Adv. Mater. 23, 523–526 (2011).

Saeki, A., Seki, S. & Tagawa, S. Electrodeless measurement of charge carrier mobility in pentacene by microwave and optical spectroscopy techniques. J. Appl. Phys. 100, 023703 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Funding Program for Next-Generation World-Leading Researches (NEXT Program), the Precursory Research for Embryonic Science and Technology (PRESTO) program of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) and a KAKENHI grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan. Y. H. and T.S. thank the JSPS for a Young Scientist Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S. conceived and designed the research. Y.H. and T.M. performed experiments. Y.H., T.M., T.S., A.S. and S.S. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and discussed it extensively.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Infomation

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Honsho, Y., Miyakai, T., Sakurai, T. et al. Evaluation of Intrinsic Charge Carrier Transport at Insulator-Semiconductor Interfaces Probed by a Non-Contact Microwave-Based Technique. Sci Rep 3, 3182 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03182

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03182

This article is cited by

-

Evaluation-oriented exploration of photo energy conversion systems: from fundamental optoelectronics and material screening to the combination with data science

Polymer Journal (2020)

-

Slow charge transfer from pentacene triplet states at the Marcus optimum

Nature Chemistry (2020)

-

Repurposing DNA-binding agents as H-bonded organic semiconductors

Nature Communications (2019)

-

Surface molecular doping of all-inorganic perovskite using zethrenes molecules

Nano Research (2019)

-

Charge carrier mobility in thin films of organic semiconductors by the gated van der Pauw method

Nature Communications (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.