Abstract

Bemisia tabaci, the whitefly vector of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV), seriously reduces tomato production and quality. Here, we report the first evidence that infection by TYLCV alters the host preferences of invasive B. tabaci B (Middle East-Minor Asia 1) and Q (Mediterranean genetic group), in which TYLCV-free B. tabaci Q preferred to settle on TYLCV-infected tomato plants over healthy ones. TYLCV-free B. tabaci B, however, preferred healthy tomato plants to TYLCV-infected plants. In contrast, TYLCV-infected B. tabaci, either B or Q, did not exhibit a preference between TYLCV-infected and TYLCV-free tomato plants. Based on gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GCMS)analysis of plant terpene volatiles, significantly more β-myrcene, thymene, β-phellandrene, caryophyllene, (+)-4-carene and α-humulene were released from the TYLCV-free tomato plants than from the TYLCV-infected ones. The results indicate TYLCV can alter the host preferences of its vector Bemisia tabaci B and Q.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) originated in the tropics and subtropics1 and has rapidly spread as a consequence of the international trade in flowers and other nursery stock. Because of its wide host range, rapid propagation and superior ability to transmit virus, B. tabaci has become one of the most important pests in field crops worldwide2. B. tabaci is a complex of numerous genetically distinct populations, previously referred to as biotypes and now recognized as cryptic species2,3,4. There are about 24 cryptic species of B. tabaci, including the two most widely distributed and invasive biotypes, B and Q, hereafter referred to as B and Q whiteflies5. B. tabaci is the only known vector of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV), which seriously reduces tomato production and quality. TYLCV is a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) plant virus in the genus begomovirus, family Geminiviridae, that originated in the Middle East6,7. Begomoviruses are transmitted by B. tabaci in a circulative manner and persist in the whitefly vector8,9,10,11.

Plant–pathogen–vector systems are characterized by complex direct and indirect interactions12,13. Virus-induced plant reactions can influence the behavior, physiology and dynamics of insect vectors in plant populations, sometimes causing behavioral changes in the vectors that favor virus transmission14. For example, a recent paper by Stafford et al. (2011)15 demonstrated that plant-infecting viruses can directly alter vector feeding behavior. The authors found that Tomato spotted wilt virus infected male thrips spent more time feeding than that of non-infected thrips. However, modification of virus “behavior” within the host plant in response to attack by herbivorous insect vectors has been addressed only very recently16.

B. tabaci B was introduced into China in the mid-1990's17, but the first incidence of TYLCV was not recorded until 2006 in Shanghai18, following the introduction and spread of the Q whitefly in 200319. The virus has since spread throughout most of China20 and the pattern of its spread has followed that of B. tabaci Q21. Researchers have hypothesized that the spread of TYLCV is closely related with the establishment and spread of B. tabaci Q20,22,23. Our recent study showed that TYLCV is benefit B. tabaci Q, but harm B. tabaci B22. In addition, TYLCV infected weed (Datura stramonium) also affects the host preference and performance of B. tabaci Q23. The results indicated that B. tabaci Q preferentially settled and oviposited on TYLCV-infected plants rather than on healthy plants. In addition, B. tabaci Q performed better on TYLCV-infected plants than on healthy plants23.

Prior studies18,19,20,21 suggest a closer mutualistic relationship that TYLCV spreads following B. tabaci Q, rather than B. In the present study, we compared the host preference of B and Q whiteflies for TYLCV-infected and healthy (i.e., virus-free) tomato plants. We also compared the volatile compounds released by healthy and TYLCV-infected tomato plants to explain the alteration in the host-selection behavior of B. tabaci. This information increases our understanding of TYLCV spread and outbreaks.

Results

Symptoms and viral load in TYLCV-infected and healthy tomato plants

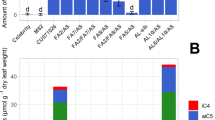

Compared to the leaves of healthy tomato plants (Fig. 1A), the leaves of TYLCV-infected plants curl upward and are yellow and stunted (Fig. 1B). The viral load was significantly higher in the TYLCV-infected plants than in the healthy plants (F1, 22 = 45367.531, p < 0.0001, Fig. 2).

Host selection

TYLCV-free B whiteflies (reared on virus-free plants) preferred to settle on TYLCV-free tomato plants over TYLCV-infected tomato plants (Fig. 3A) (F1, 56 = 50.060, p < 0.0001), whereas TYLCV-free Q whiteflies displayed the opposite behavior, settling in significantly greater proportions on TYLCV-infected plants than on TYLCV-free plants (Fig. 3C) (F1, 56 = 40.856, p < 0.0001). In contrast, the TYLCV-infected whiteflies of both B. tabaci B and Q showed no preference between the TYLCV-free and the TYLCV-infected tomato plants (Fig. 3B, D) (F1, 56 = 0.0001, p = 1.000 and F1, 56 = 0.0001, p = 1.000, respectively).

Proportion of B. tabaci B and Q individuals that settled on healthy vs. TYLCV-infected tomato plants in a choice test.

B. tabaci B and Q settling on TYLCV-free (open circles) versus TYLCV-infected tomato plants (closed circles) in two choice laboratory bioassays: (A) noninfected B. tabaci B; (B) TYLCV-infected B. tabaci B; (C) noninfected B. tabaci Q; and (D) TYLCV-infected B. tabaci Q. The numbers of adult whiteflies are also shown in the figure: the red number indicates the number of whiteflies on the healthy plant and the blue number indicates the number of whiteflies on the TYLCV-infected plant.

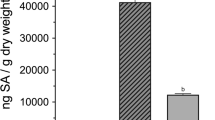

Volatiles released by TYLCV-infected and non-infected tomato plants

GC–MS chromatograms of volatiles from the TYLCV-free and the TYLCV-infected tomato plants exhibited significant qualitative and/or quantitative differences in chemical composition (Fig. 4, Table 1). TYLCV-free tomato plants emitted significantly more β-Myrcene, Thymene, β-Phellandrene, Caryophyllene and α-Humulene than did TYLCV-infected tomato plants. Furthermore, (+)-4-carene was detected only from TYLCV-free tomato plants (Fig. 4, Table 1).

Total ion chromatograms of volatile compounds released by the healthy tomato plants and the TYLCV-infected tomato plants.

The identified compounds which have significant difference between the healthy tomato plants and the TYLCV-infected tomato plants:1 = β-Myrcene, 2 = (+)-4-Carene, 3 = Thymene, 4 = β-Phellandrene, 5 = β-Caryophyllene, 6 = α-Humulene.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that the host-preference of B. tabaci is shaped by: TYLCV infected and non-infected plants; TYLCV infected and non-infected B. tabaci B and Q insects. TYLCV-free B. tabaci B were attracted to TYLCV-free tomato plants, whereas TYLCV-free B. tabaci Q were attracted to TYLCV-infected tomato plants. In addition, TYLCV-infected B. tabaci B and Q showed no preference between TYLCV-free and TYLCV-infected tomato plants. The host preferences we observed together with our recent studies20,22,23,24 to some extent explain why the spread of TYLCV in China appears to have been closely associated with the spread of B. tabaci Q rather than B.

The relationship of plant, pathogen and vector insect includes direct and indirect interactions that can be beneficial or harmful, depending on the species25,26,27. Plant viruses infect their vectors and likely affect them in at least some instances. For example, the infection with TYLCV is harmful to B. tabaci B but beneficial to Q in performance, preference of feeding behaviors and virus transmission22,25,26,27. In addition, relative to their TYLCV-free B feeding on cotton (a non-host for TYLCV), TYLCV-infected B exhibited significant reductions in survival from egg to adult; fecundity; female and male body size, whereas TYLCV-infected Q showed only marginal reductions22. While Q performed better on TYLCV-infected tomato plants than on uninfected ones, whereas B performed better on uninfected tomato plants than on TYLCV-infected ones22. The transmission of plant viruses by insect vectors has been explored for over a century28. Several studies have shown that virus-induced plant reactions shape the behavior, physiology and dynamics of the insect vectors, sometimes inducing changes in the insect vectors that favor virus transmission25,27.

Pathogen-induced plant responses may result from the changes of plant volatiles. Plant defensive compounds, specifically terpenoids, play a key role in mediating vector–pathogen mutualistic relationships. Our results show that TYLCV-free plants released significantly more β-myrcene, thymene, β-phellandrene, β-caryophyllene and α-humulene than TYLCV-infected plants (Table 1, Fig. 4). This result is consistent with that of Luan et al. (2013)29, who reported that elevation in terpenoid levels (via exogenous stem applications) reduced whitefly fitness and that suppression of terpenoid synthesis via gene silencing increased whitefly fitness. Previous study has shown that the monoterpene (+)-3-carene is associated with resistance of Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) to white pine weevil (Pissodes strobi) and that resistant trees contained significantly more (+)-3-carene than susceptible trees30. In the current study, (+)-4-carene was detected in the TYLCV-free tomato plants but not in the infected ones. In addition, virus infection often alters plant morphology, nutrition and color and these changes could affect the host preference of herbivorous vectors. With respect to nutrition, virus infection can change the amino acid composition in the phloem or in other ways change the nutritional composition of the plant tissue13,31 and thereby change the host selection by herbivorous vectors31,32. Further experiments are needed to investigate how virus-induced changes in plant volatiles, morphology, nutrition and color affect host selection by B. tabaci B and Q.

The status of the vector (virus-infected or virus-free) can also influence its behavior in a way that benefits the virus. Recently, we used the electrical penetration graph (EPG) technique to study the effect of TYLCV infection of tomato plants on vector (B. tabaci B and Q) feeding behavior24. Both B. tabaci B and Q appeared to find TYLCV-infected plants more attractive than healthy plants, probing them more quickly and exhibiting a greater number of feeding bouts. Interestingly, virus-infected whiteflies fed more often than virus-free insects and they spend more time in feeding. Because vector salivation is essential for viral transmission, this virus-mediated alteration of behavior should directly benefit TYLCV fitness24.

To our knowledge, we provide the first evidence for a direct effect of a plant virus (TYLCV) on its vector and the resulting behavioral change in B. tabaci Q may have greatly contributed to the spread of TYLCV. However, the cause of the shift in host preference between TYLCV-infected and TYLCV-free B. tabaci is unknown and should be investigated.

Methods

Plant and insect rearing

B. tabaci B was originally collected from infested cabbage, Brassica oleracea L. cv. Jing feng 1, in Beijing, China in 200433. B. tabaci Q was collected from poinsettia, Euphorbia pulcherrima Wild. ex Klotz., in Beijing, China in 200920. B and Q whiteflies were reared on healthy tomato plants, Solanum lycopersicum Mill. cv. Zhongza 9, in separate, whitefly-proof screen cages in a greenhouse under natural lighting and controlled temperature (26 ± 2°C) for six generations. The purity of each B. tabaci was monitored by sampling 15 adults per generation using a molecular diagnostic technique, CAPS (cleavage amplified polymorphic sequence) and a molecular marker, mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I genes (mtCOI)34. Tomato plants were grown in insect-proof cages under natural lighting and ambient temperatures. Inoculation was mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens using a cloned TYLCV genome (GenBank accession ID: AM282874), which was originally isolated from tomato plants in Shanghai, China18. Similar plants were not inoculated with the virus. TYLCV-infected and uninfected tomato plants with the same height were selected for experiments. Healthy and TYLCV-inoculated tomato plants at the seven true-leaf stage were used to test for TYLCV with a triple antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (TAS-ELISA). A 0.1-g sample of leaf tissue (the third leaf from the top) was ground in 1 ml of extraction buffer. Each of the two treatments was represented by 12 replicates23. A kit supplied by Adgen Phytodiagnotics (Neogen Europe (Ayr), Ltd) was used and the manufacturer's protocol was followed. Absorbance was read with a fluorescence microplate reader at 405 nm (SpectraMax M2e, Molecular Devices). The samples were considered positive for TYLCV when the mean optical density (OD) values at 405 nm were greater than three times those of the healthy controls.

Detection of TYLCV in insect and plant samples

Genomic DNA was extracted from individual whiteflies according to De Barro and Driver (1997)35 and Frohlich et al. (1999)3. The nucleic acids from plants were extracted using the Plant Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (BioTeke Biotechnology, Beijing Co, Ltd). A ~410-bp TYLCV DNA fragment was amplified using the primer pairs C473 and V6136. The resultant PCR products were electrophoresed on a 2.0% agarose gel in a 0.5 × TBE buffer and visualized by Gelview staining.

Acquisition of TYLCV by Bemisia tabaci B and Q

Plants selected to be infected with virus were inoculated at the three true-leaf stage and were assumed to be infected with TYLCV when they developed characteristic leaf-curl symptoms; TYLCV was confirmed by molecular analysis as described in the previous paragraph. About 1000 newly emerged (0–8 h post-emergence) B or Q whiteflies were placed in small cages containing the TYLCV-infected tomato plants or healthy tomato plants for 72 h.

Two-choice bioassays to assess Bemisia tabaci B and Q preferences

We determined the proportion of TYLCV-infected and TYLCV-free whiteflies that settled on TYLCV-infected and virus-free plants after 24 h. Two tomato plants of similar size and with same number of true leaves (one infected with TYLCV and the other virus free) were placed in a cage (60 cm long, 55 cm wide, 70 cm high) and about 150 B. tabaci adults of one biotype (B or Q) and one infection status (virus-infected or not infected) were released into the center of the cage (Fig. 5). The position of the two plants in the cage was randomized and cages were kept under laboratory conditions (25 ± 1°C, natural lighting). There were eight replicate cages for each of the four kinds of whiteflies: 1) infected B whiteflies (n = 8 replicates); 2) uninfected B whiteflies (n = 8); 3) infected Q whiteflies (n = 8); and 4) uninfected Q whiteflies (n = 8). The number of B. tabaci settling on each plant was recorded 3, 6, 9, 12 and 24 h after release.

Volatile collection and analysis

Leaf samples were collected from five TYLCV-free and five TYLCV-infected tomato plants. There were thus two treatments: volatile compounds released by the healthy tomato plants (n = 5 replicates); volatile compounds released by the TYLCV-infected tomato plants (n = 5). A 0.3-g quantity of leaf from each plant was subjected to gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GCMS-2010, Shimadzu) using a VF-5MS column (0.25 mm × 30 mm, J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA). The temperature program was as follows: an initial temperature of 50°C was held for 1 min, increased at 5°C/min to 240°C, held for 2 min and then increased at 30°C/min to 300°C and held for 5 min. The injection temperature was 270°C. Relative quantification was based on the peak area of each component of the volatiles. The mass spectrometer was operated in EI ionization mode at 70 eV. The temperature of the source was kept at 200°C and the interface temperatures were 280°C.

Data analysis

One-way ANOVAs were used to compare the viral load in the healthy and TYLCV-infected tomato plants. The host-settling preference between B. tabaci B and Q was tested by repeated-measures ANOVA. The concentration of individual volatile compounds emitted by TYLCV-free (healthy) versus TYLCV-infected tomato plants was compared with a Student's t-test. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (version 13.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

References

Mound, L. A. In Plant Virus Epidemiology: The Spread and Control of Insect-borne Viruses. (eds. Plumb R. T., & Thresh J. M.) 305–311 (Blackwell Ltd., 1983).

Brown, J. K., Frohlich, D. R. & Rosell, R. C. The sweetpotato or silverleaf whiteflies: biotypes of Bemisia tabaci or a species complex? Annu. Rev. Entomol. 40, 511–534 (1995).

Frohlich, D. R., Torres-Jerez, I., Bedford, I. D., Markham, P. G. & Brown, J. K. A phylogeographical analysis of the Bemisia tabaci species complex based on mitochondrial DNA markers. Mol. Ecol. 8, 1683–1691 (1999).

De Barro, P. J., Driver, F., Trueman, J. W. & Curran, J. Phylogenetic relationships of world populations of Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) using ribosomal ITS1. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 16, 29–36 (2000).

De Barro, P. J., Liu, S. S., Boykin, L. M. & Dinsdale, A. B. Bemisia tabaci: a statement of species status. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 56, 1–19 (2011).

Varma, A. & Malathi, V. G. Emerging geminivirus problems: a serious threat to crop production. Ann. Appl. Biol. 142, 145–164 (2003).

Cohen, S. & Harpaz, I. Periodic, rather than continual acquisition of a new tomato virus by its vector, the tobacco whitefly (Bemisia tabaci Gennadius). Entomol. Exp. Appl. 7, 155–166 (1964).

Brown, J. K. Molecular markers for the identification and global tracking of whitefly vector-begomovirus complexes. Virus Res. 71, 233–260 (2000).

Brown, J. K. & Czosnek, H. Whitefly transmission of plant viruses. Adv. Bot. Res. 36, 65–76 (2002).

Brown, J. K. In Bemisia: Bionomics and Management of a Global Pest (eds. Stansly P. A., & Naranjo S. E.) 31–67 (Springer Ltd., 2010).

Gill, R. J. & Brown, J. K. In Bemisia: Bionomics and Management of a Global Pest (eds. Stansly P. A., & Naranjo S. E.) 5–30 (Springer Ltd., 2010).

Belliure, B., Janssen, A., Maris, P. C., Peters, D. & Sabelis, M. W. Herbivore arthropods benefit from vectoring plant viruses. Ecol. Lett. 8, 70–79 (2005).

Stout, M. J., Thaler, J. S. & Thomma, B. P. Plant-mediated interactions between pathogenic microorganisms and herbivorous arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 51, 663–689 (2006).

Bosque-Pérez, N. A. & Eigenbrode, S. D. The influence of virus-induced changes in plants on aphid vectors: insights from luteovirus pathosystems. Virus Res. 159, 201–205 (2011).

Stafford, C. A., Walker, G. P. & Ullman, D. E. Infection with a plant virus modifies vector feeding behavior. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108, 9350–9355 (2011).

Blanc, S., Uzest, M. & Drucker, M. New research horizons in vector-transmission of plant viruses. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14, 483–491 (2011).

Luo, C. et al. The use of mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I (mtCOI) gene sequences for the identification of biotype of Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) in China. Acta Entomol. Sin. 45, 759–763 (2002).

Wu, J. B., Dai, F. M. & Zhou, X. P. First report of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus in China. Ann. Appl. Biol. 155, 439–448 (2006).

Chu, D. et al. The introduction of the exotic Q biotype of Bemisia tabaci from the Mediterranean region into China on ornamental crops. Fla. Entomol. 89, 168–174 (2006).

Pan, H. P. et al. Rapid spread of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus in China is aided differentially by two invasive whiteflies. PLoS One 7, e34817 (2012).

Pan, H. P. et al. Further spread of and domination by Bemisia tabaci biotype Q on field crops in China. J. Econ. Entomol. 104, 978–985 (2011).

Pan, H. P. et al. Differential effects of an exotic plant virus on its two closely related vectors. Sci. Rep. 3, 2230 (2013).

Chen, G. et al. Virus infection of a weed increases vector attraction to and vector fitness on the weed. Sci. Rep. 3, 2253 (2013).

Liu, B. M. et al. Multiple forms of vector manipulation by a plant-infecting virus: Bemisia tabaci and Tomato yellow leaf curl virus. J. Virol. 87, 4929–4937 (2013).

Moreno-Delafuente, A., Garzo, E., Moreno, A. & Fereres, A. A. Plant virus manipulates the behavior of its whitefly vector to enhance its transmission efficiency and spread. PLoS One 8, e61543 (2013).

Kluth, S., Kruess, A. & Tscharntke, T. Insects as vectors of plant pathogens: mutualistic and antagonistic interactions. Oecologia 133, 193–199 (2002).

Gutiérrez, S., Michalakis, Y., Munster, M. & Blanc, S. Plant feeding by insect vectors can affect life cycle, population genetics and evolution of plant viruses. Funct. Ecol. 27, 610–622 (2013).

Fernández-Calvino, L., LóPez-Abella, D. & LóPez-Moya, J. J. In General Concepts in Integrated Pest and Disease Management (eds Ciancio A., & Mukerji K. G.) 269–293 (Springer Ltd, 2007).

Luan, J. B. et al. Suppression of terpenoid synthesis in plants by a virus promotes its mutualism with vectors. Eco. Lett. 16, 390–398 (2013).

Hall, D. E. et al. An integrated genomic, proteomic and biochemical analysis of (+)-3-carene biosynthesis in Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) genotypes that are resistant or susceptible to white pine weevil. Plant J. 65, 936–948 (2011).

Mauck, K. E., De Moraes, C. M. & Mescher, M. C. Deceptive chemical signals induced by a plant virus attract insect vectors to inferior hosts. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 3600–3605 (2010).

Awmack, C. S. & Leather, S. R. Host plant quality and fecundity in herbivorous insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 47, 817–844 (2002).

Xie, W. et al. Induction effects of host plants on insecticide susceptibility and detoxification enzymes of Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). Pest. Manag. Sci. 67, 87–93 (2011).

Chu, D., Wan, F. H., Zhang, Y. J. & Brown, J. K. Change in the biotype composition of Bemisia tabaci in Shandong Province of China from 2005 to 2008. Environ. Entomol. 39, 1028–1036 (2010).

De Barro, P. J. & Driver, F. Use of RAPD PCR to distinguish the B biotype from other biotypes of Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). Aust. J. Entomol. 2, 149–152 (1997).

Ghanim, M., Sobol, I., Ghanim, M. & Czosnek, H. Horizontal transmission of begomoviruses between Bemisia tabaci biotypes. Arthropod-Plant Inte. 1, 195–204 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jonathan Sweeney (Canadian Forest Service-Atlantic Forestry Centre) for his comments and constructive criticisms. This work was funded by the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (31025020), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (6131002), the 973 Program (2013CB127602) and the Beijing Key Laboratory for Pest Control and Sustainable Cultivation of Vegetables. The granting agencies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.J.Z., Y.F., H.P.P. designed the experiment. Y.F., X.B.S., G.C. performed the experiment. W.X., S.L.W., Q.J.W., Q.S., X.Y. contributed reagents/materials. Y.F., X.G.J., H.P.P., Y.J.Z. wrote the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, Y., Jiao, X., Xie, W. et al. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus alters the host preferences of its vector Bemisia tabaci. Sci Rep 3, 2876 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02876

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02876

This article is cited by

-

A virus drives its vector to virus-susceptible plants at the cost of vector fitness

Journal of Pest Science (2024)

-

A comprehensive review: persistence, circulative transmission of begomovirus by whitefly vectors

International Journal of Tropical Insect Science (2024)

-

Performance and preference of Bemisia tabaci on tomato severe rugose virus infected tomato plants

Phytoparasitica (2023)

-

Specificity of vectoring and non-vectoring flower thrips species to pathogen-induced plant volatiles

Journal of Pest Science (2023)

-

Essential oils from two aromatic plants repel the tobacco whitefly Bemisia tabaci

Journal of Pest Science (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.