Abstract

Lithium ion batteries are attractive power sources for the consumer electronics market and are being aggressively developed for road transportation. Nevertheless, issues with safety and reliability need to be solved prior to the large-scale uptake of these batteries. There have recently been significant development and assessment of materials with resistance to mechanical abuse, with the aims of reinforcing the battery and preventing puncturing during a crash. Most of the work on battery mechanical safety has concentrated on the external packaging of batteries, with little attention being paid to the enclosed electrolyte. We report on smart multifunctional fluids that act as both highly conductive electrolytes and intrinsic mechanical protectors for lithium ion batteries. These fluids exhibit a shear thickening effect under pressure or impact and thus demonstrate excellent resistance to crushing. Also, the fluids show higher ionic conductivities and comparable redox stability windows to the commercial liquid electrolytes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The current safety issue with lithium ion battery technology represents one of the main drawbacks to introducing this system as a power source for portable electronic devices, hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) and electric vehicles (EVs), as all these applications require a high resistance to mechanical abuse. The currently available commercial systems generally use flammable electrolytes that are commonly based on organic carbonates, such as ethylene carbonate (EC), propylene carbonate (PC) and dimethyl carbonate (DMC). These electrolytes have the distinct advantages of possessing high conductivities over a wide temperature range. The abuse of lithium ion batteries, however, such as by crushing likely in an EV/HEV car accident, can trigger spontaneous heat-evolving reactions, which can lead to fires and explosions1. A general solution to this problem is the addition of physical protection packages2,3. Cells constructed with liquids must be hermetically sealed in metallic cases to prevent leakage and ensure safety in the event of excessive pressure build-up, which adds weight and volume to the batteries. Alternative solutions include the use of ionic liquids, gel polymer electrolytes, or solid state electrolytes instead of volatile carbonates4 or additives to lower the electrolyte flammability5. Unfortunately, most of these electrolyte formulations show lower conductivities and thus, the trade-off is poorer performance of the batteries.

A shear thickening fluid (STF) is a non-Newtonian fluid, in which the shear viscosity increases with an applied shear stress. It is composed of colloidal particles suspended in a carrier liquid6,7,8,9. Shear thickening phenomena have been recognized by the general public through popular videos showing people running across what appears to be water in swimming pools filled with such fluids9.Various mechanisms have been proposed for the operation of STFs, including the formation of particle clusters by hydrodynamic lubrication forces9,10, granular dilation11, or impact activated solidification12. STFs are drawing continued attention9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16, as their unique material properties make them ideal for many applications9,17,18, including liquid body armour19 and shock absorbers20.

We are eager to find out if the dynamic properties of STFs could be adopted into electrolytes to provide additional protection to battery systems against mechanical impacts. Interestingly, the essential components of STFs are very similar to those of “colloidal” or “soggy sand” electrolytes, in that both contain carrier fluids and particles. This inspired us to combine functionalities in a single application by developing novel electrolytes that not only possess the STF protective properties, but also have the advantages of the “soggy sand” electrolytes. These “soggy sand” or functional electrolytes have been extensively investigated for use in battery systems, especially for lithium ion batteries21,22,23. Ceramic particles play a very important role in different types of electrolytes. In polymer electrolytes, the addition of ceramic particles, such as TiO2, Al2O324,25, silica26,27 and AlSi28, has been used to increase conductivity and decrease crystallisation. The additional ceramic particles also resulted in significant conductivity enhancement in liquid solvents29. Solid polymer-ceramic composite materials such as protonic conductors have also found application in fuel cell applications30.

In this paper, we report on the utilization of STFs to generate novel smart fluids with multifunctional performance as a highly conductive electrolyte, whilst providing intrinsic mechanical protection for lithium ion batteries. These fluids exhibit the shear thickening effect under pressure or impact and thus demonstrate excellent tolerance to crushing, which could significantly improve the mechanical safety of batteries. Also, the fluids show higher ionic conductivities than commercial liquid electrolytes and comparable redox stability. Lithium ion batteries using multifunctional fluids provide higher capacities, especially at high charge/discharge rates. The smart multifunctional fluids reported in this work can be achieved by the simple addition of fumed silica to a currently used electrolyte (1 M LiFP6 in EC/DMC) in commercial lithium ion batteries. This simple and easily scalable fabrication method can be applied to commercial lithium ion batteries without significant additional costs.

Results

Introduction of the shear thickening property into commercial electrolytes

Initially, we introduced the shear thickening property into a commercial electrolyte. A series of compositions of a commercial liquid electrolyte (1 M LiPF6 in EC/DMC (1:1)) with different weight fractions of fumed silica nanoparticles were prepared, as described in the Methods section and the Supplementary Information. The fumed silica used is S5505 (Sigma-Aldrich). Its primary structure consists of branched aggregates formed by the fusion of nanoparticles (average crystal size of 14 nm), as can be observed by atomic force microscopy (AFM; see Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Information). This aggregated structure is responsible for the unique properties of fumed silica31. Note that the aggregates cannot be disrupted further by shear. This type of fumed silica was selected, as it has been used to form stable dispersions and facilitate STFs in previous research32. The dispersion stability of fumed silica in organic media has been extensively investigated33 and their unusual stability has been explored for several decades34. In order to keep the particles dispersed in a medium, the forces between particles must be taken into account. Dispersed nanoparticles frequently undergo collisions due to Brownian motion. Whether or not the particles will separate after colliding is dependent on the sum of attractive and repulsive forces acting between the particles. There are several typical forces governing nanoparticle stability, which include van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions, solvation forces and osmotic and entropic interactions related to molecular adsorption35,36. Dispersions of hydrophilic fumed silica in a range of organic media and the formation of stable sols through strong hydrogen bonding have been reported. The fumed silica forms stable, low-viscosity sols exhibiting shear thickening behavior in a host of liquids33. In our system, the solvent (EC/DMC) is believed to form hydrogen bond with the silanols on the fumed silica surface, resulting in the formation of a solvation layer around each particle. This leads to repulsive solvation forces, which stabilize the fumed silica particles so that the system behaves as a stable fumed silica sol. In addition, both rheological testing and visual observations provided further evidence of the system stability at room temperature, as described in the Methods section and the Supplementary Information (see Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Information). Although all the experiments were conducted at room temperature in our system, it is also noted that the temperature could play an important role in fumed silica dispersions and stability. For instance, temperature worked as an optional and simple way to tailor the viscoelastic properties and to control the microstructure of fumed silica dispersions37,38.

The rheological properties of the electrolytes were investigated using a rotating parallel plate rheometer (MCR 301, Anton Paar, Germany). The measurements were conducted by varying the shear rate from 1.00 to 1000 s−1 under a 1 mm gap between the measurement geometry and the base. The bare electrolyte behaves in an approximately steady way as a Newtonian fluid with 0.004 Pa·s viscosity (Fig. 1). The electrolyte containing a lower amount of fumed silica (weight fraction 6.3% silica in the commercial electrolyte) does not show any obvious shear thickening region, although its viscosity is much higher than that of the bare electrolyte. The shear thickening phenomenon can be observed, however, with a higher fumed silica content (weight fraction 9.1% silica in the commercial electrolyte) and such samples show an obvious shear thickening regime. There is, however, an initial shear thinning regime before the shear thickening, but at the critical shear rate value of 3.6 s−1, the electrolyte viscosity increases from 10.8 Pa·s to 73.8 Pa·s, although there is also a subsequent shear thinning regime at very high shear rates. Compared with the bare electrolyte, it can be concluded that the shear thickening is due to the fumed silica and that the fumed silica nanoparticles contribute to the increased viscosity of the new electrolyte. A higher weight fraction of 10.7% silica in the commercial electrolyte was also tested, which exhibited similar rheological properties as that of 9.1% weight fraction sample. But it shows a slightly higher viscosity in the shear thickening region.

Figure 1 provides possible theoretical representations of fumed silica particles at different shear stages. At the initial state of liquid flow, the fumed silica particles are suspended in the electrolyte. In the first shear thinning regime layered structures of fumed silica particles are formed. Then, in the shear thickening regime, the fumed silica particles form hydroclusters that impede flow. The shear thickening indicates a possible transition from a thermodynamic Brownian dominated regime to a hydrodynamically dominated regime, where fumed silica particles form hydroclusters that become structurally more effective for dissipating mechanical energy. The rheological representation is a rapid increase in bulk viscosity at a high shear rate39. It is also possible that the change from shear thickening to shear thinning at very high shear rates is naturally due to a limiting mechanical modulus of the hydroclusters of fumed silica nanoparticles, namely the elastohydrodynamic lubrication limit of shear thickening40. So, in the highest shear rate range, the hydrodynamicity dominates and pushes all the hydroclusters along with the flow, resulting in the decrease in the viscosity.

Electrochemical properties of the batteries with shear thickening electrolyte

Secondly, the ionic conductivities of the composite electrolytes were tested (Fig. 2). The performance of the commercial electrolyte with fumed silica (1 M LiPF6 in EC/DMC) highlights a significant variation in the effective overall ionic conductivity with the fumed silica weight fraction (ω). The composite conductivity exhibits typical percolation behaviour, which is expected for a composite with enhanced interfacial conductivity41, i.e., low conductivity at low oxide content, which increases to a marked maximum, before decreasing at higher weight fractions. Similar phenomena have been reported by Maier's group29,42. The conductivity enhancment generated by the addition of fumed silica is likely to be attributable to an adsorption of the anion (PF6) by the acidic oxide and the subsequent break-up of the ion pair, thereby increasing the Li+ concentration in the space charge layer surrounding the oxide particles. At a lower fumed silica fraction, the composite exhibits colloidal behavior, with double layer repulsion reducing percolation, resulting in very poor conductivity. When the particles are forced into a sufficiently narrow spacing, the interfacial conductivity is percolative29. At very high weight fractions, the fumed silica particles could be in direct contacts, thereby introducing porosity effects that eventually cause a blocking of the pathways by “dry” oxide particles. The maximum conductivity enhancement for 1 M LiPF6 in EC/DMC (1:1) was observed for the STF fluid with 10.7 wt.% silica, with a value of σ = 1.93 × 10−2 S cm−1, which is significantly higher than for the commercial electrolyte without fumed silica addition (σ = 2 × 10−3 S cm−1). The inset to Fig. 2 shows that the excellent conductivity of the STF composite electrolyte is reversible after impact tests. For example, the conductivity of the STF electrolyte with 9.1 wt.% silica is stable at 4.5 × 10−3 S cm−1 after 5 continuous impact tests with crush (impact) energy of 0.568 J.

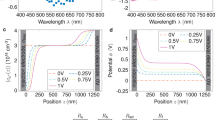

In order to determine if the electrolyte with shear thickening fluid (STF) would continue to function in a lithium ion battery, 2032 type coin cells using both commercially available cathodes (LiFePO4 or LiCoO2) and anode (graphite) as the working electrodes, Li foil as the counter electrode and the STF as the electrolyte were assembled in an argon-filled glove box. The rate capabilities of LiFePO4 half cells using the commercial electrolyte (1 M LiPF6 in EC/DMC) with or without fumed silica (9.1 wt.% silica) were compared (Fig. 3(a)). At lower current rates, e.g. 0.1 C, both cells display a similar capacity. When the current rate is greater than 0.2 C, the rate capability of cells using the STF electrolyte is enhanced compared to that of cells using the neat commercial electrolyte, again demonstrating that the fumed silica nanoparticles facilitate lithium ion transport in the electrolyte, in a good agreement with the ionic conductivity results. The discharge capacity of cells using the commercial electrolyte was 145 mAh g−1 at 0.1 C, but decreased to 134 mAh g−1 at 0.5 C, 120 mAh g−1 at 2 C and 102 mAh g−1 at 5 C. In contrast, the cells using the STF electrolyte maintained 140 mAh g−1 at 0.5 C, 124 mAh g−1 at 2 C and 110 mAh g−1 at 5 C, demonstrating that the STF electrolyte enhances the rate capability of the LiFePO4 cells. A significant enhancement effect of the STF electrolyte on the rate performance of graphite half cells was also observed (Fig. 3(b)). Furthermore, the charge/discharge cycling performances of cells using the two electrolytes were also compared (Fig. 3(b), inset). The cell using the STF electrolyte shows a slightly higher reversible capacity, although the cells with both electrolytes (with/without silica particles) exhibit excellent cycling performance. No apparent change (Fig. 3(c)) between the Nyquist plots of the cell using the STF electrolyte before and after impact testing was observed, indicating that the STF electrolyte behaves reversibly if given enough relaxation time following impact. The cell using the STF electrolyte maintained its electrochemical capacity after a series of impact tests (Fig. 3(d)). Note that an impact was applied at the end of the 47th charge-discharge cycle. Only in the 48th cycle (the following cycle after impact) did the capacity slightly decrease, which was likely due to a shear thickening response of the electrolyte under impact that generates increased viscosity and lower conductivity. After the external impact was removed, the electrolyte gradually returned to its pre-impact state, as demonstrated by the stable cell performance in the post impact cycles. The charge/discharge curves of the cell in the 47th cycle (the last cycle before the impact test) and the 48th cycle (the first cycle after the impact test) are both shown (Fig. 3(d), insets). The partial discharge curve during the impact test with a crush energy of 0.284 J is also shown in Fig. S3. It can be seen that the cell was still working effectively after the impact test.

(a) Comparison of rate performance of LiFePO4 electrode in STF electrolyte (SiO2 weight fraction 9.1%) with that in normal 1 M LiPF6 in EC/DMC electrolyte at different current rates. The cells were cycled in the voltage range of 2.2–3.8 V. (b) Rate performance of graphite electrode with STF electrolyte (SiO2 weight fraction is 9.1%) or normal 1 M LiPF6 in EC/DMC electrolyte at different current rates. Inset in (b) compares the cycling performance of graphite electrode in normal electrolyte and in STF electrolyte. Both cells show excellent cycling stability, while the electrode in STF electrolyte exhibits slightly higher capacity. (c) Electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) of graphite electrode in STF electrolyte before and after impact test. (d) Cycling performance of graphite anode in STF electrolyte. Impact with energy of 0.284 J was applied to the testing cell at the end of the 47th cycle.

The effect of the shear thickening fluids on the anti-crushing capability of the batteries

The effect of the shear thickening fluids on the battery mechanical integrity was also tested. Specially designed safety tests mimicking crushing conditions were conducted using lithium cells containing STF or commercial LiPF6 in EC/DMC (1:1) as electrolytes, to test the mechanical protection feature of the STF. Figure 4(a) reveals that LiFePO4 cells using commercial electrolyte and composite electrolyte without any STF effect (showing a shear thinning effect) were crushed and short circuited at the low impact energy of 0.426 J. The electrolyte with 6.3 wt.% silica particles, which doesn't show the shear thickening effect (as demonstrated in Fig. 1), cannot offer improved protection; therefore, any possible effect of fumed silica particles as an inhibitor (separator) to prevent a short circuit from the electrodes that are crushed into contact can be excluded. In contrast, the cells using STF electrolyte tolerated impact energy of up to 0.568 J, higher than the energy that the normal electrolyte cells can safely tolerate. Similar effects were also observed for the graphite cells (Fig. S4) and LiCoO2 cells (Fig. S5), suggesting that using STF electrolyte could be a very effective way to improve not only the battery performance, but also battery safety. In order to confirm the effects of the shear thickening properties on the mechanical properties of the batteries, similar impact tests were conducted using a different cell configuration. The repeatable findings have further confirmed that the cells using STF electrolyte tolerate higher impact energy (Figs. S4, S5 and S6).

(a) Discharge curve of LiFePO4 electrode in the STF electrolyte of EC/DMC/LiPF6 with 9.1 wt.% SiO2. Impacts with different energies were applied to the cell during the discharge. For comparison, the discharge curves of LiFePO4 electrode in bare EC/DMC/LiPF6 electrolyte and composite electrolyte of EC/DMC/LiPF6 with 6.3 wt.% SiO2 (showing shear thinning effect) are also shown in the inset of (a). The STF electrolyte provides intrinsic protection to the cell, tolerating impact energy as high as 0.568 J, while the cells with the bare or composite electrolyte without shear thickening are short-circuited at the low impact energy of 0.426 J. (b–d) Schematic representation of the protective mechanism of STF electrolyte.

Discussion

The schematic diagram in Fig. 4(b–d) describes the possible changes in the electrolytes with/without any influence from the shear-thickening property when an impact is applied. Fig. 4(b) shows the condition of the electrolyte before the impact, where the particles repel each other slightly and the fumed silica ceramic particles enhance ionic conductivity. The low viscosity colloidal suspension acts as a lubricant for the particles, which makes them disperse ‘uniformly’ throughout the liquid without clumping together or settling to the bottom. When the impact force is applied to the electrolyte (Fig. 4(c)), it overcomes the repulsive interparticle forces to promote ceramic particle clustering (or an impact-jammed solid)10,12 within the electrolyte. This causes the electrolyte to adopt a solid-like state and becomes less penetrable. The concentrated fumed silica-filled electrolyte shows a typical shear thickening performance, as well as the formation of hydrodynamic clusters of fumed silica particles and associated increase of suspension viscosity. Note that shear stress is a product of the viscosity and the shear rate; and a product of the shear stress and the shear rate represents the capacity for mechanical power dissipation. According to Hooke's model the increased viscosity would slow the energy dissipation due to the elementary work of the restoring force. In other words, the increased viscosity in the electrolytes with a significant shear thickening property has produced a slower conversion of the work done by the restoring force into heat compared to the electrolytes without the fumed silica particles. Although the increased viscosity may have increased the energy transfer from the work of the resistant force to heat, compared with the work of the restoring force, it would be small. The overall effect of the phenomenon is the effective enhancement of the rigidity of the cell, along with a slow increase in temperature in the electrolyte after the impact. When the energy from the impact dissipates (Fig. 4(d)), the particles repel one another again and the hydroclusters fall apart, so that the pseudo-solid substance reverts to the original liquid status. Conversely, upon impact, the battery system without a shear thickening effect easily experiences a large deformation and a rapid increase in temperature during the impact that could ignite the solvents.

The fluids are field responsive and can undergo a sudden fluid-solid transition within a certain range of shear rates. At a critical shear rate, the fluid experiences mesostructural reorganization and the formation of clustered particles, leading to enhancement of the mechanical properties of the fluid, however, the impact resistance of STF depends on not only the fluid shear thickening property, but also the particle strength. At higher impact velocities, the impact resistance of STF is governed by particle strength43. When the impact rate is beyond the critical rate, the dynamic strength of the particles is overcome and local particle fracture and deformation would therefore result in a loss of strength in the stiffened fluid. At this stage, the material response is dominated simply by its bulk density. This feature of STF has been reported in its application to ballistic impacts and puncture resistance. Previous results demonstrated a significant enhancement in ballistic penetration and different puncture resistances (such as under spike and stab) due to additional shear thickening of the fluid44 and they also indicated the loss of ballistic resistance of STFs at high impact velocities45. The strength variations of STFs at high strain rates and stresses were also investigated46. Our results are consistent with those studies and illustrate that the STF electrolyte under the investigated shear rates developed an excellent resistance to crushing, which could significantly improve the mechanical safety. We are also aware of the limitation of STFs in terms of their impact resistance. We believe, however, that with a careful selection of suspended particles, electrolytes and other parameters of particles and electrolytes, such as concentration, size, distribution, shape and interaction of particles and viscosity of electrolytes, the resistance range can be controlled and therefore, the STF would be able to enhance the safety of the electrolyte under certain conditions. The information reported here indicates that electrolytes based on STFs improve the functional capacity of batteries. The multifunctional role of electrolytes could be extended to other electrolytic cells, capacitors or fuel cells, in which the electrolyte not only serves as the medium for charge transfer, but also provides protection from crash impacts. Batteries with these characteristics will revolutionize vehicular transportation and military energy requirements. The use of STF electrolytes will eliminate the need to include extra weight or volume to achieve protection and therefore, fewer trade-offs will be needed to optimize energy density and simple manufacturing. The concept is also under evaluation in other electrolyte systems, such as polymers, gels and ionic liquids.

Methods

Synthesis of composite electrolytes

The composite electrolytes were synthesized by mixing different weight ratios of fumed silica particles (S5505, Sigma-Aldrich), in a commercial electrolyte consisting of ethylene carbonate/dimethyl carbonate (EC/DMC) (volume ratio 1:1) with 1 M LiPF6 (Jiangsu Guotai) in an argon-filled glove box. Stable suspensions of EC/DMC/LiPF6 with 6.3 wt.% SiO2, EC/DMC/LiPF6 with 9.1 wt.% SiO2 and EC/DMC/LiPF6 with 10.7 wt.% SiO2 were obtained and then kept in the glove box until ready for use. The fumed silica particles were dried by vacuum suction before using. The fumed silica primary particles are irreversibly fused into large aggregates that cannot be disrupted by shear. The suspensions were transparent and showed no visual evidence of phase separation, precipitation, or increases in turbidity over long periods of time. Such a phenomenon has also been observed by other groups33.

Electrochemical measurements

The cell performance was tested galvanostatically at different current densities at room temperature using coin-type half cells (2032 type). The cells were assembled in an argon-filled glove box, in which commercial LiFePO4 and graphite electrodes (MIT Corporation) and homemade LiCoO2 electrodes were utilized as working electrodes, respectively; Li metal was used as the counter electrode; microporous polyethylene (Celgard 2500) was used as the separator; and the synthesized composite solutions (the bare EC/DMC/LiPF6, EC/DMC/LiPF6 with 6.3 wt.% SiO2, EC/DMC/LiPF6 with 9.1 wt.% SiO2 and EC/DMC/LiPF6 with 10.7 wt.% SiO2) were used as electrolytes, respectively. The LiCoO2 electrodes were prepared from the active materials (LiCoO2), carbon black and polyvinylidene fluoride binder (PVDF, Sigma-Aldrich) at a weight ratio of 8:1:1. The coated electrodes were dried at 100°C for 20 hours and then roll-pressed before using. The thickness of the LiCoO2 electrodes was around 0.1 mm. The cells were cycled in the voltage range of 2.2–3.8 V (versus Li/Li+) for LiFePO4 half cells, 3.0–4.3 V (versus Li/Li+) for LiCoO2 half cells and 0.01–1.5 V (versus Li/Li+) for graphite half cells. The impedance changes of the cells before and after impact were measured using an electrochemistry workstation (CHI604C). Specifically, for ionic conductivity analysis, electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) tests of the bare electrolyte and the electrolytes with different weight ratios of SiO2 were carried out in a two platinum electrode conductivity cell in a glove box using an electrochemistry workstation (CHI604C) over the frequency range from 1 Hz to 0.1 MHz. The ionic conductivity of all samples was calculated from the intercept of the linear curve spike with the real axis obtained from the impedance data.

Impact tests

The coin-type cells (2032 type) were also used for the impact tests. The LiFePO4 electrodes, LiCoO2 electrodes and graphite electrodes were assembled respectively into the three types of half cells in an argon-filled glove box along with the electrolytes: bare EC/DMC/LiPF6, EC/DMC/LiPF6 with 6.3 wt.% SiO2, EC/DMC/LiPF6 with 9.1 wt.% SiO2 and EC/DMC/LiPF6 with 10.7 wt.% SiO2. Once the cells were assembled, they were taken out of the glove box and then placed in an oven at 40°C for 4 hours to allow the electrolytes to soak sufficiently into the separator and electrodes. The impact tests were carried out using a slideway device (Fig. S7) that allowed a stainless steel truncated cone (140 g) to slide from a certain height to impact the battery cells (Fig. S8) while they were discharged. A NEWARE battery tester was used to collect the discharge curves and a force sensor was employed to measure the impact force. Although differences in cell composition resulted in varying levels of impact tolerance, neither the bare electrolyte nor the composite electrolyte with 6.3 wt.% SiO2 (showing a shear thinning effect) offered improved protection to the battery (Figs. S4, S5 and S6). The composite electrolytes with 9.1 wt.% SiO2 and 10.7 wt.% SiO2 (with shearing thickening effect) were found to provide additional protection, however. Several parallel experiments were carried out on the three types of cell and reproducible results were obtained.

References

Smith, B. Chevrolet volt battery incident overview report: with three reports. (Washington, D.C.: NHTSA, 2012).

Kizilel, R., Sabbah, R., Selman, J. R. & Al-Hallaj, S. An alternative cooling system to enhance the safety of li-ion battery packs. J Power Sources 194, 1105–1112 (2009).

Kizilel, R. et al. Passive control of temperature excursion and uniformity in high-energy Li-ion battery packs at high current and ambient temperature. J Power Sources 183, 370–375 (2008).

Lu, Y., Moganty, S. S., Schaefer, J. L. & Archer, L. A. Ionic liquid-nanoparticle hybrid electrolytes. J Mater Chem 22, 4066–4072 (2012).

Choi, N. S. et al. Challenges facing lithium batteries and electrical double-layer capacitors. Angew Chem, Int Edit 51, 9994–10024 (2012).

Barnes, H. A. Shear-thickening (dilatancy) in suspensions of nonaggregating solid particles dispersed in Newtonian liquids. J Rheol 33, 329–366 (1989).

Maranzano, B. J. & Wagner, N. J. Flow-small angle neutron scattering measurements of colloidal dispersion microstructure evolution through the shear thickening transition. J Chem Phys 117, 10291–10302 (2002).

Catherall, A. A., Melrose, J. R. & Ball, R. C. Shear thickening and order-disorder effects in concentrated colloids at high shear rates. J Rheol 44, 1–25 (2000).

Wagner, N. J. & Brady, J. F. Shear thickening in colloidal dispersions. Phys Today 62, 27–32 (2009).

Cheng, X., McCoy, J. H., Israelachvili, J. N. & Cohen, I. Imaging the microscopic structure of shear thinning and thickening colloidal suspensions. Science 333, 1276–1279 (2011).

Brown, E. et al. Generality of shear thickening in dense suspensions. Nature Mater 9, 220–224 (2010).

Waitukaitis, S. R. & Jaeger, H. M. Impact-activated solidification of dense suspensions via dynamic jamming fronts. Nature 487, 205–209 (2012).

Brown, E. & Jaeger, H. Dynamic jamming point for shear thickening suspensions. Phys Rev Lett 103, 086001 (2009).

Smith, M. I., Besseling, R., Cates, M. E. & Bertola, V. Dilatancy in the flow and fracture of stretched colloidal suspensions. Nature Commun 1, 114–115 (2010).

Bi, D., Zhang, J., Chakraborty, B. & Behringer, R. P. Jamming by shear. Nature 480, 355–358 (2011).

Roché, M., Kellay, H. & Stone, H. A. Heterogeneity and the role of normal stresses during the extensional thinning of non-Brownian shear-thickening fluids. Phys Rev Lett 107, 134503 (2011).

Beiersdorfer, P., Layne, D., Magee, E. W. & Katz, J. I. Viscoelastic suppression of gravity-driven counterflow instability. Phys Rev Lett 106, 058301 (2011).

Liu, B., Shelley, M. & Zhang, J. Focused force transmission through an aqueous suspension of granules. Phys Rev Lett 105, 188301 (2010).

Li, X. et al. Preparation of body armour material of Kevlar fabric treated with colloidal silica nanocomposite. Plast Rubber Compos 37, 223–226 (2008).

Zhang, X. Z., Li, W. H. & Gong, X. L. The rheology of shear thickening fluid (STF) and the dynamic performance of an STF-filled damper. Smart Mater Struct 17, 035027 (2008).

Kang, X. Nonaqueous liquid electrolytes for lithium-based rechargeable batteries. Chem Rev 104, 4303–4417 (2004).

Lee, Y. S. et al. Composite gel polymer electrolytes containing core-shell structured SiO2(Li+) particles for lithium-ion polymer batteries. Electrochem Commun 17, 18–21 (2012).

Das, S. K., Mandal, S. S. & Bhattacharyya, A. J. Ionic conductivity, mechanical strength and Li-ion battery performance of mono-functional and bi-functional (“Janus”) “soggy sand” electrolyte. Energy Environ Sci 4, 1391–1399 (2011).

Croce, F., Appetecchi, G. B., Persi, L. & Scrosati, B. Nanocomposite polymer electrolytes for lithium batteries. Nature 394, 456–458 (1998).

Pitawala, H. M. J. C. et al. Effect of plasticizers (EC or PC) on the ionic conductivity and thermal properties of the (PEO)9LiTf: Al2O3 nanocomposite polymer electrolyte system. J Solid State Chem 12, 783–789 (2008).

Chen-Yang, Y. W. et al. Influence of silica aerogel on the properties of polyethylene oxide-based nanocomposite polymer electrolytes for lithium battery. J Power Sources 182, 340–348 (2008).

Shen, C. et al. Physicochemical properties of poly(ethylene oxide)-based composite polymer electrolytes with a silane-modified mesoporous silica SBA-15. Electrochim Acta 54, 3490–3494 (2009).

Bronstein, L. M. et al. Design of organic-inorganic solid polymer electrolytes: synthesis, structure and properties. J Mater Chem 14, 1812–1820 (2004).

Bhattacharyya, A. J. & Maier, J. Second phase effects on the conductivity of non-aqueous salt solutions: "soggy sand electrolytes". Adv Mater 16, 811–814 (2004).

Kumar, B. & Fellner, J. P. Polymer–ceramic composite protonic conductors. J Power Sources 123, 132–136 (2003).

Demir, M. M., Menceloglu, Y. Z. & Erman, B. Aggregation of fillers blended into random elastomeric networks: theory and comparison with experiments. Macromol Chem Phys 207, 1515–1524 (2006).

Benitez, R., Contreras, S. & Goldfarb, J. Dispersions of methylated silica in mixed solvents. J Colloid Interf Sci 36, 146–150 (1971).

Raghavan, S. R., Walls, H. J. & Khan, S. A. Rheology of silica dispersions in organic liquids: new evidence for solvation forces dictated by hydrogen bonding. Langmuir 16, 7920–7930 (2000).

Atkins, D. T. & Ninham, B. W. Surface and structural forces measured between silica surfaces in 1,2-ethanediol. Colloid Surface A 129–130, 23–32 (1997).

Russel, W. B. The Dynamics of Colloidal Systems. (University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1987).

Russel, W. B., Saville, D. A. & Schowalter, W. R. Colloidal Dispersion. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1989).

Wu, X. J. et al. A rheological study on temperature dependent microstructural changes of fumed silica gels in dodecane. Soft Matter 8, 10457–10463 (2012).

Sanchez, A. Colloidal gels of fumed silica: Microstructure, surface interactions and temperature effects. PhD thesis, North Carolina State University (2006).

Bergström, L. Shear thinning and shear thickening of concentrated ceramic suspensions. Colloid Surface A 133, 151–155 (1998).

Mewis, J. & Wagner, N. J. Colloidal Suspension Rheology. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2012), pp. 277–281.

Bunde, A. & Dieterich, W. Percolation in composites. J Electroceramics 5, 81–92 (2000).

Jarosik, A., Pfaffenhuber, C., Bunde, A. & Maier, J. Electrochemical investigations of polyethylene glycol-based “soggy sand” electrolytes – from the local mechanism to the overall conduction. Adv Funct Mater 21, 3961–3966 (2011).

Petel, O. E. et al. The effect of particle strength on the ballistic resistance of shear thickening fluids. Appl Phys Lett 102, 064103–064104 (2013).

Srivastava, A., Majumdar, A. & Butola, B. S. Improving the impact resistance of textile structures by using shear thickening fluids: a review. Crit Rev Solid State 37, 115–129 (2012).

Lee, B. W. & Kim, C. G. Computational analysis of shear thickening fluid impregnated fabrics subjected to ballistic impacts. Adv Compos Mater 21, 177–192 (2012).

Lee, Y., Wetzel, E. D. & Wagner, N. J. The ballistic impact characteristics of Kevlar® woven fabrics impregnated with a colloidal shear thickening fluid. J Mater Sci 38, 2825–2833 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the DSTO Fellowship Program from the Defence Science and Technology Organisation, Australia. J. H. and F. T. C. thank CSIRO Energy Transformed Flagship for financial support. The authors thank Mr. T. Radtke, Dr. L. Chen, Dr. M. Alderton, Prof. C.H. Wang and Dr. C. Woodruff for assistance with the manuscript preparation, Dr. E. Wetzel for discussions and Dr. N. Beagley and Dr. S. Oldfield for reviewing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D., W.H.L., Z.P.G. and J.H. designed the study, carried out experiments and wrote the manuscript. T.F.T., Q.M., P.Z., F.T.C. and W.Y. performed experiments and analysed data. All authors contributed to manuscript presentation and figure preparation.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Smart Multifunctional Fluids for Lithium Ion Batteries: Enhanced Rate Performance and Intrinsic Mechanical Protection

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, J., Tian, T., Meng, Q. et al. Smart Multifunctional Fluids for Lithium Ion Batteries: Enhanced Rate Performance and Intrinsic Mechanical Protection. Sci Rep 3, 2485 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02485

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02485

This article is cited by

-

Influence of dispersion liquid and silica concentration on rheological properties of shear thickening fluids (STFs)

Rheologica Acta (2023)

-

Rheological and Interfacial Properties of Colloidal Electrolytes

Chinese Journal of Polymer Science (2019)

-

Enhancement in the supercapacitive storage performance of MnCO3 using SiOx nanofluid-based electrolyte

Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry (2018)

-

Experimental and modelling study of the effect of temperature on shear thickening fluids

Korea-Australia Rheology Journal (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.