Abstract

Endocannabinoids are small signaling lipids, with 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) implicated in modulating axonal growth and synaptic plasticity. The concept of short-range extracellular signaling by endocannabinoids is supported by the lack of trans-synaptic 2-AG signaling in mice lacking sn-1-diacylglycerol lipases (DAGLs), synthesizing 2-AG. Nevertheless, how far endocannabinoids can spread extracellularly to evoke physiological responses at CB1 cannabinoid receptors (CB1Rs) remains poorly understood. Here, we first show that cholinergic innervation of CA1 pyramidal cells of the hippocampus is sensitive to the genetic disruption of 2-AG signaling in DAGLα null mice. Next, we exploit a hybrid COS-7-cholinergic neuron co-culture system to demonstrate that heterologous DAGLα overexpression spherically excludes cholinergic growth cones from 2-AG-rich extracellular environments and minimizes cell-cell contact in vitro. CB1R-mediated exclusion responses lasted 3 days, indicating sustained spherical 2-AG availability. Overall, these data suggest that extracellular 2-AG concentrations can be sufficient to activate CB1Rs along discrete spherical boundaries to modulate neuronal responsiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Endocannabinoids, particularly 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG)1,2,3 and anandamide (AEA)4,5,6, modulate synaptic neurotransmission by acting on molecularly diverse cannabinoid receptors in the brain1,5,7. 2-AG is chiefly recognized as the retrograde messenger1,8 engaging presynaptic CB1 cannabinoid receptors (CB1Rs) to scale neurotransmitter release1,9. The general molecular paradigm for 2-AG metabolism and signaling at adult synapses in the cerebral cortex is that sn-1-diacylglycerol lipase α (DAGLα), rather than DAGLβ2,10, synthesizes 2-AG11 when anchored at dendritic spines of pyramidal cells apposing excitatory CB1R+ terminals12. Despite the exceptional concentration of CB1Rs in some perisomatic inhibitory terminals in the cerebral cortex13, DAGLs are absent from subsynaptic dendritic stretches receiving inhibitory afferents12. Exceptions to this general rule may exist, including the “invaginated” inhibitory synapse of the basolateral amygdala9 with particularly rich DAGLα accumulation postsynaptically. Therefore, the molecular arrangement of 2-AG signaling at many synapses suggests that 2-AG spreads over considerable distances extracellularly from its synthesis locus to exert heterosynaptic effects14. The lack of 2-AG-mediated retrograde signaling in DAGLα−/− mice also supports trans-synaptic 2-AG signaling2,10.

Data from molecular pharmacology studies, primarily on AEA15,16, suggest that endocannabinoids could assume a preferred orientation and conformation when partitioned in membrane bilayers and activate CB1Rs via fast lateral diffusion. A likely prerequisite for endocannabinoids to act as juxtacellular retrograde messengers is their precisely-timed and activity-dependent release. Therefore, saturable, time and temperature sensitive protein carrier-mediated mechanisms have evolved, allowing transmembrane endocannabinoid transport17,18 to operate in a cell-type specific manner19. Accordingly, electrophysiology recordings under quasi-physiological conditions suggest spatially restricted endocannabinoid action, i.e. ligand spread up to 20–22 μm20,21. However, strong postsynaptic depolarization at lower temperatures indiscriminately inhibits CB1R+ interneurons via endocannabinoids within a radius of ~100 μm22. These variations in endocannabinoid spread are supported by the temperature sensitivity of fast endocannabinoid synthesis (and presumed release)23, occurring at <50 ms at 37°C upon initiation of postsynaptic activity. Nevertheless, the molecular characterization of DAGLα-dependent extracellular 2-AG action is yet awaited.

The contribution of endocannabinoid signaling to brain development is increasingly recognized11,24,25,26,27,28. These studies, focusing on 2-AG signaling, have uncovered that the molecular architecture of endocannabinoid signaling during neurodevelopment is profoundly different from that in adult brain ( Fig. 1a ). This includes longer distances between prospective pre- and postsynaptic partners, dynamic changes to their orientation during growth cone (GC) navigation and the lack of perisynaptic glia that could curtail lateral endocannabinoid diffusion by harboring monoacylglycerol lipase (MGL), a major 2-AG inactivating enzyme29. Given the coincident targeting of CB1Rs and DAGLα/β11,26, 2-AG signaling can operate cell-autonomously in GCs. In contrast, MGL is actively excluded from GCs28 until synaptogenesis concludes27 to allow 2-AG-mediated forward neurite growth. Differential partitioning of DAGLα/β and MGL in subcellular growth domains28 could reconcile differences in molecular requirements of cell-autonomous and short-range paracrine 2-AG signaling, the latter likely be operational during the fasciculation and coordinated pathfinding of long-range axons, including corticopetal cholinergic afferents28. Nevertheless, the physical properties and physiological contribution of intercellular 2-AG signals to brain development remain elusive.

DAGLα localization in the fetal cholinergic basal forebrain.

(a) Schema of 2-AG signaling during fetal development and in adulthood. Note the lack of both MGL in growth cones28 and glial 2-AG inactivation during development, allowing 2-AG spread. (b,b1) CB1R mRNA in the medial septum (ms) at embryonic day (E)18.5 and postnatal day 1 (P1). (b2,b3) The lack of hybridization signal in sense control experiments (neocortex, P1) confirmed detection specificity. (c,c1) A subpopulation of ChAT+ septal neurons was immunoreactive for CB1Rs in neonates. (c2–c4) In the neonatal hippocampus, cholinergic afferents likely harbored CB1Rs given the lack of physical signal separation for ChAT and CB1R immunoreactivities. Solid and open arrowheads pinpoint the presence and lack of co-localization for select marker combinations, respectively. (c5) Colocalization coefficients for cholinergic (ChAT+) and CB1R+ boutons in the CA1 subfield of the neonatal hippocampus. Data on dual-labeled terminal subsets were expressed as the percentage of all cholinergic or CB1R-containing synapses per field of view. (d–d1) A subpopulation of p75NTR+ neurons expressed DAGLα28. p75NTR+ neurons, assumed to acquire cholinergic phenotype46, were generally situated proximal to DAGLα+ cells (arrowheads). (d2–d4) Representative images of cholinergic neurites coursing along DAGLα+ neurons and of adjacent p75NTR+-DAGLα cell pairs in the medial septum. (d5) Quantitative analysis of the portion of p75NTR+ processes that apposed DAGLα+ perikarya (representative configuration: d3,d4) and of p75NTR+ perikarya in the vicinity (<10 μm) of a DAGLα+ cell. (e,e1) p75NTR+ fibers (dashed lines) were found interspersed with DAGLα+ processes in the E18.5/P1 corpus callosum. Arrowheads indicate physical separation between fibers. (e2) Distances between p75NTR+ and DAGLα+ parallel fibers. Abbreviations: cc, corpus callosum; ml, midline; ls, lateral septum; pyr, pyramidal cells. Data were expressed as means ± s.e.m.; Scale bars = 100 μm (b1), 20 μm (c), 10 μm (c2,d2–d4), 5 μm (e1), 2 μm (c4).

While endocannabinoid uptake as a means of rapid signal termination received significant attention, mechanistic insights in regulated 2-AG or AEA release from cells are fragmented30, even though a synaptic activation-dependent, compartmentalized mechanism is appealing to explain the kinetics of retrograde signaling. Therefore, it is important to determine how far 2-AG can spread at near-physiological temperatures in intact cell systems. Here, we used fetal cholinergic neurons whose spatially confined axonal projections provide an experimentally tractable model to explore the contribution of juxtacellular 2-AG signals to the development of corticopetal cholinergic projections. We have taken advantage of CB1R-mediated cholinergic GC navigation28 upon modulating DAGLα activity as a means to determine spatial constraints of 2-AG availability and action in vitro.

Results

2-AG signaling shapes cholinergic morphology

CB1R mRNA was detected by in situ hybridization in the medial septum on E18.5 and P1 ( Fig. 1b–b 3 ), coincident with the neurochemical maturation of cholinergic neurons as marked by their co-expression of choline-acetyltransferase (ChAT; Fig. 1c 1 ), rate-limiting acetylcholine synthesis31 and the low-affinity neurotrophin receptor p7528 (p75NTR, Fig. 1d ). CB1R immunoreactivity was localized to the somata of ChAT+ neurons (ChAT; Fig. 1c,c 1 ; Supplementary Fig. 1a–b 1 ). CB1Rs co-existed in a subset of ChAT+ axons ( Fig. 1c 2 –c 4 ), amassing to ~15% of the total cholinergic population ( Fig. 1c 5 ). Quantitative morphometry revealed that cholinergic contribution to the total CB1R+ synaptic input in the hippocampus was similarly limited ( Fig. 1c 5 ).

In the developing forebrain27, including the basal forebrain28, 2-AG synthesis by DAGLα(β) is spatially and temporally coordinated with the expression of CB1Rs. In cholinergic territories, p75NTR+ neurons expressed DAGLα ( Fig. 1d,d 1 ; Supplementary Fig. 1c–d 1 ). Notably, ~20% of all p75NTR+ axons coursed along or around non-cholinergic DAGLα+ neurons in the medial septum, defined as <10 μm spatial segregation by high-resolution laser-scanning microscopy ( Fig. 1d 2 –d 5 ). Conspicuously, p75NTR+ or DAGLα+ neurons were often clustered with inter-space intervals of <10 μm ( Fig. 1d 5 ). In the corpus callosum, p75NTR+ axons, putative corticopetal cholinergic projections32, coursed parallel to DAGLα+ fibers ( Fig. 1e–e 2 ). These cellular arrangements suggest that intercellular 2-AG signaling might modulate the developmental organization of cholinergic projections.

Genetic deletion of DAGLα impairs cholinergic innervation of the hippocampus

If 2-AG signaling is physiologically involved in cholinergic axonal growth or post-synaptic target selection (both have been reported in CB1R−/− mice28,33) then genetic disruption of 2-AG synthesis in DAGLα−/− or DAGLβ−/− mice2,10 could impair cholinergic pathfinding. We tested this hypothesis by quantitative morphometry in the CA1 subfield of the adult hippocampus, which receives particularly dense cholinergic innervation34. We find that, irrespective of the deletion strategy in DAGLα−/− mice on C57Bl6 background2,10, cholinergic innervation of hippocampal pyramidal cells was altered, manifesting as disordered perisomatic ChAT+ innervation ( Fig. 2a–a 2 ). The number of perisomatic cholinergic “baskets”, defined as ChAT+ boutons in a minimum of three quadrants around a pyramidal cell soma ( Fig. 2a 2 ; Supplementary Fig. 1e ), significantly decreased in DAGLα−/− mice ( Fig. 2b ). This loss of synaptic innervation was not biased by the altered density of pyramidal cells or other morphometric variables related to hippocampal size or cell distribution (data not shown). The cholinergic phenotype brought about by DAGLα deletion exceeded that in DAGLβ−/− mice, in which alterations to cholinergic synapse distribution were milder and more stochastic, precluding statistical significance ( Fig. 2b 1 ). The overall density ( Fig. 2b 1 ) and average size ( Fig. 2c ) of ChAT+ boutons remained unchanged. These data support the primary reliance of nervous system organization and function on DAGLα2,10 and suggest that 2-AG signaling is required for the spatial organization, rather than synaptogenesis per se, of cholinergic hippocampal projections.

Genetic deletion of DAGLα alters cholinergic innervation of the adult mouse hippocampus.

(a,a1) DAGLα knock-out mice (DAGLα-KO) presented altered cholinergic afferentation of the hippocampus, manifesting as the loss of perisomatic “baskets” around CA1 pyramidal cells (*). Note the complete lack of DAGLα staining in the DAGLα-KO mouse, confirming staining specificity and genotype. (a2) Paired high-resolution images of complete (in wild-type) or fragmented (in DAGLα-KO and DAGLβ-KO) perisomatic “baskets” (arrowheads) in the CA1 pyramidal layer. (b,b1) The number of cholinergic perisomatic “baskets” decreased significantly in the CA1 pyramidal layer of DAGLα-KO but not DAGLβ-KO mice (b). In contrast, the cumulative density of ChAT+ presynaptic profiles did not change (b1), emphasizing disrupted synapse targeting rather than impaired synaptogenesis. Grey and white circles differentiate knock-out animals on C57Bl6 background (n = 2–3/group) obtained from Tanimura et al.10 and Gao et al.2, respectively. (c). Particle profiling tools revealed no appreciable difference amongst the size of ChAT+ synaptic profiles from DAGL knock-outs. Abbreviations: n, nucleus; n.s., non-significant; Pyr, pyramidal layer; **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Scale bars = 20 μm (a,a1), 5 μm (a2).

In vitro manipulation of DAGLα in a two-cell system

If extracellular 2-AG signaling is physiologically relevant for cholinergic neurite outgrowth and pathfinding then this may be modeled in a two-cell system with genetically restricted DAGL manipulation of a single cell type. Here, we used COS-7 cells, stably transfected with a DAGLα-V5 construct (“COS-7-DAGLα cells”; Fig. 3a,b ) and normally considered as being devoid of an endocannabinoid system35. COS-7-DAGLα cells exhibited membranous DAGLα localization ( Fig. 3b ), which is expected of a protein with four trans-membrane domains11. Western analysis showed that COS-7 cells successfully overexpressed full-length DAGLα protein relative to “parent” cells ( Fig. 3c ). Mass-spectrometry confirmed increased 2-AG contents in COS-7-DAGLα cell pellets ( Fig. 3c 1 ). 2-AG production was THL sensitive, supporting DAGL dependence. DAGL(α/β) activity can affect cell morphology or proliferation36. We excluded a DAGLα-induced change in COS-7 cell morphology (surface area; Fig. 3d–d 2 ) or density ( Fig. 3d 3 ) over 3 days in vitro (DIV), which we used as a cut-off in co-culture experiments (see below).

DAGLα overexpression does not affect COS-7 physiology and induces 2-AG accumulation.

(a–b2) Endogenously produced DAGLα in non-transfected COS-7 (“parent”) cells is undetectable by indirect immunohistochemistry (open arrowheads; a–a2). In contrast, DAGLα, when highly expressed in COS-7 cells transfected with a DAGLα-V5 vector, accumulates in the plasma membrane (solid arrowheads; b–b2). (c) COS-7-DAGLα cells expressed DAGLα protein and (c1) synthesized 2-AG in a tetrahydrolipstatin (THL)-sensitive fashion. (d–d3) DAGLα overexpression did not influence COS-7 cell morphology (d,d1), including their surface area (d2) and density in culture (d3). Data were normalized to mean values from COS-7 “parent” cells. Abbreviations: n.s. = non significant. Scale bars = 20 μm (b,d1).

Short-range intercellular 2-AG signaling

To precisely dissect the effective area and cellular consequences of extracellular 2-AG signals, we constructed an in vitro cell system by using COS-7 cells heterologously overexpressing DAGLα11 as “2-AG hot-spots”, interspersed with cholinergic (p75NTR+) basal forebrain neurons ( Fig. 4a ). If 2-AG acts as a short-range extracellular cue then DAGLα overexpression might be expected to modulate GC localization and motility – but not general neurite elongation or cell migration – proximal to COS-7-DAGLα cells ( Fig. 4a 1 ). When co-culturing cholinergic neurons and COS-7-DAGLα cells for 1-3DIV, we found that “parent” COS-7 cells attracted cholinergic neurites, which coursed on or along COS-7 plasmalemmas already by 1DIV ( Fig. 4b–b 2 ). Accordingly, the distance between cholinergic GCs and the opposing membrane of COS-7 cells gradually decreased as a factor of time (20.6 ± 3.6 μm (1DIV); 12.5 ± 1.7 μm (2DIV); 9.2 ± 1.7 μm (3DIV); Fig. 4b 2 ). In contrast, 55.0% of cholinergic GCs were prevented from approaching the proximal COS-7 cell's plasmalemma upon DAGLα overexpression by 3DIV (vs. 19.2% in control; p < 0.001; Fig. 4b 2 ). DAGLα overexpression spherically excluded cholinergic GCs, as reflected by their significantly increased distance to the surface of COS-7-DAGLα cells (9.2 ± 1.7 μm (“parent”) vs. 17.7 ± 1.7 μm (DAGLα; 3DIV); p = 0.037; Fig. 4b 3 ).

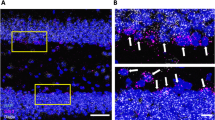

Extracellular 2-AG promotes spherical exclusion of cholinergic growth cones (GCs).

(a) Cholinergic neurons from C56Bl6 mice co-cultured with COS-7-DAGLα cells allowed measurement of GC exclusion triggered by extracellular 2-AG. (a1) Schema of the in vitro method and the parameters determined and plotted in (b2–f). (b,b1) Representative images of cholinergic GCs apposing control (“parent”) or DAGLα-overexpressing COS-7 cells (COS-7-DAGLα). Arrows point to filopodia. Dotted lines indicate the membrane surface of COS-7(-DAGLα) cells with arrowheads pinpointing their proximal segment facing the GCs. (b2) Percentage of GCs that were unable to make contact upon DAGLα overexpression. (b3) The distance (in μm) of cholinergic GCs from COS-7(-DAGLα) cells. GCs gradually approached COS-7 cells in control. DAGLα overexpression occluded this response, suggesting GC repulsion by extracellular 2-AG. DAGLα overexpression did not affect the angle at which the GC faced the proximal surface of the COS-7 cell (c), neurite outgrowth per se (d) or the distance of cholinergic somata from COS-7 cells (e). Upon making contact, cholinergic neurites were no longer affected by DAGLα overexpression (f). Data were averaged from 3 (1,2DIV) or 4 (3DIV) separate experiments; n = 25–77 cells/group. Abbreviations: DIV, days in vitro; N, neuron; n, nucleus. Data were expressed as means ± s.e.m. except for (b3) showing a combination of individual data points and mean values (horizontal lines); **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, +p < 0.1. Scale bars = 10 μm (a), 3 μm (b).

DAGLα overexpression did not affect the angle at which GCs approached COS-7-DAGLα cells ( Fig. 4c ), the length of cholinergic neurites ( Fig. 4d ), the distance between cholinergic and COS-7 somata ( Fig. 4e ) and the survival of p75NTR+ neurons in vitro (data not shown), excluding delayed morphogenesis or neuronal migration as confounding factors. Once cholinergic GCs contacted COS-7(-DAGLα) cells, their neurites gradually extended on the COS-7 cells' surface ( Fig. 4f ), confirming that neurite outgrowth was not impaired. Yet DAGLα overexpression no longer affected neurite growth, confining endocannabinoid action to affecting GC motility but no other forms of e.g. contact guidance. Overall, these data suggest that focal and extracellular 2-AG can alter the positioning of cholinergic GCs.

Motile growth cones contain DAGLs26,28. Therefore, we excluded redistribution of DAGLα in the neurites of cholinergic neurons co-cultured with COS-7-DAGLα cells. In the absence of appreciable changes in DAGLα localization or content ( Supplementary Fig. 2 ; see ref. 28 for comparison), we conclude that DAGLα overexpression in COS-7 cells was the only variable that contributed to the above phenomena, supporting a role for intercellular 2-AG signaling.

DAGL and CB1R dependence of growth responses

We exploited pharmacological tools to exclude off-target effects of DAGLα overexpression. DAGL inhibition by either THL or O-384137 significantly decreased the probability of GC exclusion (76.8% (DAGLα) vs. 16.7% (DAGLα + THL [p = 0.001]; or 29.9% (DAGLα + O-3841) [p = 0.005]; Fig. 5a,b ). Inhibition of CB1Rs by AM 251 or O-2050 diminished the number of GCs failing to make cell surface contact (76.9% (DAGLα) vs. 50.5% (DAGLα + AM 251; p = 0.08) or 38.5% (DAGLα + O-2050; p = 0.007); Fig. 5a,b ). Both classes of drugs tended to reduce the distance of GCs that had not contacted COS-7-DAGLα cells from the target cell's surface ( Fig. 5c ). We attribute this impartial rescue to the small percentage of excluded GCs under pharmacological conditions, leading to larger deviations in sampled GC cohorts. The above treatments did not affect the angle of GC approach ( Fig. 5d ), neurite outgrowth ( Fig. 5e ) or the distance between cholinergic neurons and COS-7 cells ( Fig. 5f ). Our data suggest that CB1Rs modulate GC motility and directional growth around DAGLα “hot spots” in vitro.

Pharmacological inhibition of DAGLα or CB1Rs prevents chemorepulsion of cholinergic growth cones (GC).

(a) Representative photomicrographs of cholinergic neurite-COS-7(-DAGLα) cell contacts upon inhibiting DAGLs (THL, O-3841) or CB1R antagonism (AM 251, O-2050) at 3DIV. Arrows point to cholinergic neurites. Dotted lines indicate the membrane surface of COS-7(-DAGLα) cells. (b,c) Disrupting excess 2-AG signaling prevented chemorepulsion of cholinergic GCs. None of the ligands affected the angle of approach (d), neurite outgrowth (e), or cholinergic-to-COS-7 cell distance (f). Data were expressed as means ± s.e.m. except for (c) where individual data points and mean values (horizontal lines) were plotted. Data were averaged from duplicate samples from 2 independent experiments; n = 12–30 cells/group. **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, +p < 0.1. Scale bar = 20 μm (a).

Discussion

Major inferences of the present report include that fetal cholinergic basal forebrain neurons express CB1Rs to sense extracellular endocannabinoid signals. This finding is supported by CB1R expression in a subset of adult cholinergic projection neurons of the medial septum38 and their terminals in the hippocampus, where CB1R antagonism increases acetylcholine efflux39. Thus, we identified subcortical neurons, which use a continuum of endocannabinoid signals to time and scale presynapse development, spatial segregation and adult function40.

Cholinergic axons coursed along DAGL+ neurons (<10 μm) towards the hippocampus ( Fig. 1d–d 4 ). This observation is significant since it identifies a cellular niche and developmental event where intercellular endocannabinoid signaling might potentially take place to facilitate the directional growth of cholinergic projections. This finding is compatible with the concept40 that elevated focal 2-AG concentrations can participate in facilitating neuron migration26 and delineate repulsive corridors for neuronal pathfinding. The relative paucity of MGL expression in the neonatal cerebrum27 irrespective of its neuronal or glial origin (that is, thalamocortical axons are the main source of MGL by birth) and its subcellular exclusion from growth domains28 emphasize that DAGL activity and paracrine 2-AG signaling can critically shape the complexity and orientation of corticopetal axons originating in the basal forebrain.

The physicochemical properties of intercellular 2-AG signaling dissected here describe key parameters of the postsynaptic target selection deficit previously observed upon conditional CB1R deletion in the cortical circuitry26,33. In particular, the sensitivity of cholinergic morphogenesis to scaling 2-AG signaling (genetic disruption in DAGLα−/− mice) identifies DAGLα11 as a molecular determinant of neuronal morphology and connectivity. The cholinergic phenotype brought about in DAGLα−/− mice exceeded that of DAGLβ−/− mice. These data support the reliance of nervous system organization and function on DAGLα2,10 during the perinatal period.

The spatial segregation of DAGL and CB1R expression at adult synapses assumes the ability of 2-AG to support short-range intercellular communication1,10. To determine the spatial spread of 2-AG extracellularly, we have constructed a two-cell system allowing the use of cholinergic growth cone navigation as a functional read-out. GC collapsing responses are usually measured in minutes33. The fact that cholinergic neurites (and GCs) evaded 2-AG rich extracellular domains in the proximity of DAGLα-COS-7 cells for days reinforces the hypothesis40 that the temporal disruption of time-locked and sustained developmental endocannabinoid signals by i.e. cannabis can impair the organization of synaptic connectivity maps in the fetal brain.

Since DAGL overexpression in COS-7 cells increased 2-AG concentrations, we suggest that 2-AG is a candidate signal lipid to induce GC collapse via an extracellular mode of action. Endocannabinoid transport relies on intracellular carriers41 and transmembrane transport systems17. Given the considerable (~15 μm) distance at which 2-AG can accumulate extracellularly, we predict that 2-AG transporters and extracellular carriers might exist to ensure the precision of extracellular ligand availability and turnover. Yet future studies must reveal the contribution of intracellular carriers and transmembrane transport systems ensuring the precision and dynamics of extracellular ligand availability and turnover along short time scales.

Our in vitro studies provide the first attempt to dissociate between cell-autonomous24 and intercellular 2-AG signaling. These data, together with in vivo observations in CB1R or DAGL knock-outs, suggest that autocrine signaling arrangements might be poised to scale the rate of neurite outgrowth28, while intercellular 2-AG signals could underscore GC steering decisions33,42, ultimately affecting synapse positioning.

Methods

Animals, ethical approval and drug treatment

Neuroanatomy studies in tissues from C57Bl6/J (n = 6) on embryonic day (E) 18.5 and postnatal day (P)1/2 were performed as described27. Young adult DAGLα−/− (n = 6), DAGLβ−/− (n = 4) and age-matched wild-type controls (n = 4)2,10 were processed to phenotype cholinergic innervation ( Fig. 2 ). Adult CB1R−/− mice43 (n = 2) were used to validate antibody specificity ( Supplementary Fig. 1a–b 1 ). The Home Office of the United Kingdom approved all experimental designs and procedures, which adhered to the European Communities Council Directive (86/609/EEC). Efforts were made to minimize the number of animals and their suffering throughout the experiments.

Histochemistry

Multiple immunofluorescence labeling of fetal mouse brains27 was performed by applying select cocktails of affinity-purified primary antibodies, including rabbit or guinea-pig anti-CB1R (C-terminal; 1:1,000)44, guinea-pig anti-DAGLα (1:500; gift of K. Mackie, for characterization see Supplementary Fig. 1c–d 1 ), rabbit anti-p75NTR (1:2,000; Promega)28 and goat anti-ChAT (1:200, Millipore)28. DyLight488/549/649- or carbocyanine (Cy)2/3/5-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:300; Jackson) were used to visualize primary antibody binding. Hoechst 33,342 (1:10,000; Sigma) was used as nuclear counterstain.

Heterologous DAGLα expression

COS-7 cells transfected with a DAGLα construct carrying a V5-tag (COS-DAGLα, clone 12) were grown as described11. We verified DAGLα overexpression by lysing COS-7-DAGLα and non-transfected COS-7 (“parent”) cells in modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing 5 mM NaF, 5 mM Na3VO4, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% N-octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (Calbiochem) and a mixture of protease inhibitors (Complete®, EDTA-free, Roche), denatured in Laemmli's buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Membranes were blocked in Odyssey blocking buffer (LiCor Biosciences, 1 h), exposed to guinea pig anti-DAGLα (1:500); mouse anti-V5 (1:2,000; Invitrogen) and mouse anti-β-actin (1:10,000; Sigma) primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, developed by appropriate combinations of IRDye800 and IRDye680 antibodies (LiCor Biosciences, 1:10,000, 1 h) and analyzed on a LiCor Odyssey IR imager.

Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

COS-7 “parent” or COS-7-DAGLα cells were grown for 2 days in vitro (DIV) and serum starved. MGL activity was inhibited by JZL184 (200 nM)45 for 30 min prior to cell scraping to allow 2-AG enrichment. In parallel assays, tetrahydrolipstatin (THL, 1 μM) was used for 20 min to verify the contribution of DAGLα to 2-AG synthesis. Next, media were aspirated; cells were scraped, sedimented by rapid centrifugation and snap-frozen in liquid N2. Fig. 3c 1 shows data from a representative experiment with all groups processed in parallel. 2-AG concentrations in cell pellets were determined using a solid-phase extraction liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method as described27. Results were normalized to the protein concentration of the samples. Note, however, that increased protein concentrations when overexpressing DAGLα likely led to an underestimate of the actual 2-AG concentration in transfected COS-7 cells.

Neuron – COS-7 cell co-cultures, drug treatments

Basal forebrain neurons were isolated using a dorsal approach on E16.528. In experiments assessing CB1R expression in neurochemically-identified cholinergic cells, fetal brains were enzymatically dissociated and plated at a density of 50,000 cells/well in poly-D-lysine (PDL)-coated 24-well plates. For co-cultures, COS-7 parent or COS-7-DAGLα cells (2,500 cells/well in 24 well-plate format) were grown on PDL-coated coverslips overnight, with primary forebrain neurons seeded thereon at a density of 25,000 cells/well and grown for 1, 2 or 3 DIV. Cultures were maintained in DMEM/F12 (1:1) containing B27 supplement (2%), L-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (all from Invitrogen). Co-cultures on coverslips were processed for quantitative morphometry as described28 using combinations of the following antibodies: mouse anti-β-III-tubulin (TUJ1, 1:2,000; Promega), guinea-pig anti-DAGLα (1:500) and rabbit anti-p75NTR (1:2,000; Promega). p75NTR was used to identify cholinergic projection neurons and their primary neurite, the quiescent axon, in vitro. DAGLs' enzymatic activity was inhibited by THL (1 μM, Sigma) or O-3841 (1 μM; gift of R. Razdan and V. di Marzo). CB1R dependence of neurite outgrowth was verified by applying the CB1R antagonists AM 251 (1 μM, Tocris) or O-2050 (200 nM, Tocris).

Quantitative morphometry

Images were acquired on a Zeiss 710LSM confocal laser-scanning microscope28. Co-localization of select histochemical marker pairs was verified by capturing serial orthogonal z image stacks at 63× primary magnification (pinhole: 20 μm, 2048 × 2048 pixel resolution). The co-existence of immunosignals was accepted if these were present without physical signal separation in ≤1.0-μm optical slices and overlapped in all three (x, y and z) dimensions within individual cellular domains28.

ChAT immunoreactive profiles were analyzed at 40× primary magnification in the pyramidal layer of the hippocampal CA1 subfield from DAGLα−/−, DAGLβ−/− or wild-type mice (1 μm optical thickness; n = 2–3 sections/animal). High-resolution images were exported into the UTHSCSA ImageTool (version 3.00) to determine the density of ChAT+ terminal profiles expressed per 1,000 μm2. Cholinergic “baskets”, defined as cholinergic ChAT+ terminal-like boutons engulfing a Hoechst+ nucleus in the CA1 pyramidal layer on at least two quadrants ( Fig. 2a 2 ) were counted in ImageJ 1.45 s and expressed per 1,000 μm2. The size difference of ChAT+ synaptic profiles ( Fig. 2c ) was excluded after binning immunoreactive particles by size in view frames containing 2,048 × 2,048 pixels (ImageJ 1.45 s). Co-localization of cholinergic processes with CB1Rs ( Fig. 1b 5 )27, cholinergic contact to DAGLα+ cells ( Fig. 1c 5 ) and the distance of p75+ and DAGLα+ processes from one another ( Fig. 1d 2 ) were measured using the ZEN2010 software (Zeiss).

Quantitative morphometry of p75NTR+ neurons in vitro included: (i) the percentage of sampled neurites that came into contact with COS-7/COS-7-DAGLα cells, (ii) distance of individual p75NTR+ GCs from the most proximal COS-7 “parent” or COS-7-DAGLα cells, (iii) the degree at which a GC approached the plasmalemmal surface of the proximal COS-7 cell, (iv) the length of the axon segment overlaying the COS-7/COS-7-DAGLα cell (termed “contact length”), (v) the entire length of individual axons and (vi) the distance between COS-7 and p75NTR+ neuronal somata ( Fig. 4a 1 depicts the parameters collected). The presence of DAGLα in cholinergic GCs was investigated by plotting DAGLα immunoreactivity from the tip of the growth cone along the putative axon ( Supplementary Fig. S2a,a 1 ) as described27,28. Data were expressed as arbitrary units (a.u., scaled: 0–85; ImageJ 1.45 s). COS-7 cell surface area (μm2) and density (cell number/101,643 μm2) were measured to exclude DAGLα overexpression-induced artifacts ( Fig. 3d–d 3 ) and normalized to those of COS-7 “parent” cells. Images were processed using the ZEN2010 software package (Zeiss). The brightness or contrast of confocal laser-scanning micrographs was occasionally linearly enhanced. Multi-panel images were assembled in CorelDraw X5 (Corel Corp.).

Statistics

Experiments were performed in at least duplicates with n = 12–30 neurites (including GC parameters) per group analyzed from at least two coverslips in individual experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA (Tukey's post-hoc test) or Student's t-test (independent samples design) at the p < 0.05 level of statistical significance. GC exclusion was tested using non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. Results were expressed as means ± s.e.m.

References

Kano, M., Ohno-Shosaku, T., Hashimotodani, Y., Uchigashima, M. & Watanabe, M. Endocannabinoid-mediated control of synaptic transmission. Physiol Rev. 89, 309–380 (2009).

Gao, Y. et al. Loss of retrograde endocannabinoid signaling and reduced adult neurogenesis in diacylglycerol lipase knock-out mice. J. Neurosci. 30, 2017–2024 (2010).

Peterfi, Z. et al. Endocannabinoid-mediated long-term depression of afferent excitatory synapses in hippocampal pyramidal cells and GABAergic interneurons. J. Neurosci. 32, 14448–14463 (2012).

Kreitzer, A. C. & Regehr, W. G. Retrograde signaling by endocannabinoids. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 12, 324–330 (2002).

Grueter, B. A., Brasnjo, G. & Malenka, R. C. Postsynaptic TRPV1 triggers cell type-specific long-term depression in the nucleus accumbens. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1519–1525 (2010).

Kim, J. & Alger, B. E. Reduction in endocannabinoid tone is a homeostatic mechanism for specific inhibitory synapses. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 592–600 (2010).

Sylantyev, S., Jensen, T. P., Ross, R. A. & Rusakov, D. A. Cannabinoid- and lysophosphatidylinositol-sensitive receptor GPR55 boosts neurotransmitter release at central synapses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 5193–5198 (2013).

Alger, B. E. Retrograde signaling in the regulation of synaptic transmission: focus on endocannabinoids. Prog. Neurobiol. 68, 247–286 (2002).

Yoshida, T. et al. Unique inhibitory synapse with particularly rich endocannabinoid signaling machinery on pyramidal neurons in basal amygdaloid nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 3059–3064 (2011).

Tanimura, A. et al. The endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol produced by diacylglycerol lipase alpha mediates retrograde suppression of synaptic transmission. Neuron 65, 320–327 (2010).

Bisogno, T. et al. Cloning of the first sn1-DAG lipases points to the spatial and temporal regulation of endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. J. Cell Biol. 163, 463–468 (2003).

Yoshida, T. et al. Localization of diacylglycerol lipase-alpha around postsynaptic spine suggests close proximity between production site of an endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol and presynaptic cannabinoid CB1 receptor. J. Neurosci. 26, 4740–4751 (2006).

Tsou, K., Mackie, K., Sanudo-Pena, M. C. & Walker, J. M. Cannabinoid CB1 receptors are localized primarily on cholecystokinin-containing GABAergic interneurons in the rat hippocampal formation. Neuroscience 93, 969–975 (1999).

Regehr, W. G., Carey, M. R. & Best, A. R. Activity-dependent regulation of synapses by retrograde messengers. Neuron 63, 154–170 (2009).

Tian, X., Guo, J., Yao, F., Yang, D. P. & Makriyannis, A. The conformation, location and dynamic properties of the endocannabinoid ligand anandamide in a membrane bilayer. J Biol. Chem. 280, 29788–29795 (2005).

Makriyannis, A., Tian, X. & Guo, J. How lipophilic cannabinergic ligands reach their receptor sites. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 77, 210–218 (2005).

Fu, J. et al. A catalytically silent FAAH-1 variant drives anandamide transport in neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 64–69 (2012).

Beltramo, M. et al. Functional role of high-affinity anandamide transport, as revealed by selective inhibition. Science 277, 1094–1097 (1997).

Hillard, C. J. & Jarrahian, A. The movement of N-arachidonoylethanolamine (anandamide) across cellular membranes. Chem. Phys. Lipids 108, 123–134 (2000).

Brown, S. P., Brenowitz, S. D. & Regehr, W. G. Brief presynaptic bursts evoke synapse-specific retrograde inhibition mediated by endogenous cannabinoids. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 1048–1057 (2003).

Wilson, R. I. & Nicoll, R. A. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signalling at hippocampal synapses. Nature 410, 588–592 (2001).

Kreitzer, A. C., Carter, A. G. & Regehr, W. G. Inhibition of interneuron firing extends the spread of endocannabinoid signaling in the cerebellum. Neuron 34, 787–796 (2002).

Heinbockel, T. et al. Endocannabinoid signaling dynamics probed with optical tools. J Neurosci. 25, 9449–9459 (2005).

Wu, C. S. et al. Requirement of cannabinoid CB(1) receptors in cortical pyramidal neurons for appropriate development of corticothalamic and thalamocortical projections. Eur. J. Neurosci. 32, 693–706 (2010).

Begbie, J., Doherty, P. & Graham, A. Cannabinoid receptor, CB1, expression follows neuronal differentiation in the early chick embryo. J. Anat. 205, 213–218 (2004).

Mulder, J. et al. Endocannabinoid signaling controls pyramidal cell specification and long-range axon patterning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 8760–8765 (2008).

Keimpema, E. et al. Differential subcellular recruitment of monoacylglycerol lipase generates spatial specificity of 2-arachidonoyl glycerol signaling during axonal pathfinding. J. Neurosci. 30, 13992–14007 (2010).

Keimpema, E. et al. Nerve growth factor scales endocannabinoid signaling by regulating monoacylglycerol lipase turnover in developing cholinergic neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 1935–1940 (2013).

Tanimura, A. et al. Synapse type-independent degradation of the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol after retrograde synaptic suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 12195–12200 (2012).

Adermark, L. & Lovinger, D. M. Retrograde endocannabinoid signaling at striatal synapses requires a regulated postsynaptic release step. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 20564–20569 (2007).

Fonnum, F. The ‘compartmentation’ of choline acetyltransferase within the synaptosome. Biochem. J 103, 262–270 (1967).

Hartig, W., Seeger, J., Naumann, T., Brauer, K. & Bruckner, G. Selective in vivo fluorescence labelling of cholinergic neurons containing p75(NTR) in the rat basal forebrain. Brain Res. 808, 155–165 (1998).

Berghuis, P. et al. Hardwiring the brain: endocannabinoids shape neuronal connectivity. Science 316, 1212–1216 (2007).

Freund, T. F. & Buzsaki, G. Interneurons of the hippocampus. Hippocampus 6, 347–470 (1996).

Kaczocha, M., Glaser, S. T., Chae, J., Brown, D. A. & Deutsch, D. G. Lipid droplets are novel sites of N-acylethanolamine inactivation by fatty acid amide hydrolase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 2796–2806 (2010).

Jung, K. M., Astarita, G., Thongkham, D. & Piomelli, D. Diacylglycerol lipase-alpha and -beta control neurite outgrowth in neuro-2a cells through distinct molecular mechanisms. Mol. Pharmacol. 80, 60–67 (2011).

Bisogno, T. et al. Development of the first potent and specific inhibitors of endocannabinoid biosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761, 205–212 (2006).

Nyiri, G. et al. GABAB and CB1 cannabinoid receptor expression identifies two types of septal cholinergic neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 21, 3034–3042 (2005).

Degroot, A. et al. CB1 receptor antagonism increases hippocampal acetylcholine release: site and mechanism of action. Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 1236–1245 (2006).

Harkany, T., Mackie, K. & Doherty, P. Wiring and firing neuronal networks: endocannabinoids take center stage. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 18, 338–345 (2008).

Kaczocha, M., Glaser, S. T. & Deutsch, D. G. Identification of intracellular carriers for the endocannabinoid anandamide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 6375–6380 (2009).

Argaw, A. et al. Concerted action of CB1 cannabinoid receptor and deleted in colorectal cancer in axon guidance. J. Neurosci. 31, 1489–1499 (2011).

Zimmer, A., Zimmer, A. M., Hohmann, A. G., Herkenham, M. & Bonner, T. I. Increased mortality, hypoactivity and hypoalgesia in cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96, 5780–5785 (1999).

Kawamura, Y. et al. The CB1 cannabinoid receptor is the major cannabinoid receptor at excitatory presynaptic sites in the hippocampus and cerebellum. J. Neurosci. 26, 2991–3001 (2006).

Long, J. Z. et al. Selective blockade of 2-arachidonoylglycerol hydrolysis produces cannabinoid behavioral effects. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 37–44 (2009).

Tremere, L. A., Pinaud, R., Grosche, J., Hartig, W. & Rasmusson, D. D. Antibody for human p75 LNTR identifies cholinergic basal forebrain of non-primate species. Neuroreport 11, 2177–2183 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We thank R.A. Ross for valuable discussions, K. Mackie and H. Martens for antibodies, R. Razdan and V. di Marzo for the DAGL inhibitor O-3841 and G. Cameron for mass spectrometry. This work was supported by the Scottish Universities Life Science Alliance (T.H.), Vetenskapsrådet (T.H.), Hjärnfonden (T.H.), European Commission (HEALTH-F2-2007-201159; T.H.), Novo Nordisk Foundation (T.H.) and National Institutes of Health (DA023214; Y.L.H. and T.H.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.H. conceived the general idea of this study; E.K., Y.L.H., P.D. and T.H. designed experiments; F.H., C.H., Y.L.H., P.D., M.W., K.S. and M.K. contributed unique reagents and tools; E.K., A.A., C.H. and K.M. performed experiments and analyzed data; E.K. and T.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript and approved its submission.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Keimpema, E., Alpár, A., Howell, F. et al. Diacylglycerol lipase α manipulation reveals developmental roles for intercellular endocannabinoid signaling. Sci Rep 3, 2093 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02093

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02093

This article is cited by

-

CB1 antagonism increases excitatory synaptogenesis in a cortical spheroid model of fetal brain development

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Programming of neural cells by (endo)cannabinoids: from physiological rules to emerging therapies

Nature Reviews Neuroscience (2014)

-

Endocannabinoids modulate cortical development by configuring Slit2/Robo1 signalling

Nature Communications (2014)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.