Abstract

Mechanical flexibility and compatibility of printing processes are key advantage that organic electronic devices have over conventional inorganic devices. However, one of the major remaining issues for organic devices is insufficient mechanical durability of printed electrodes. Here we have investigated the mechanical durability of both p-type and n-type organic thin-film transistors (TFTs) with ink-jet printed silver electrodes from silver nanoparticle inks. The modified silver nanoparticle inks enabled the strong adhesion to the underlying polymer layer and the fabricated organic TFTs exhibited excellent reproducibility in the bending cycle tests. The strong channel length dependence on the strain sensitivity was observed in both p-type and n-type organic TFTs. The organic TFTs with a short-channel exhibited higher sensitivity to the bending strain. These results suggest that the flexible organic TFTs with printed silver electrodes have excellent mechanical durability and are useful for bending and strain sensors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mechanical flexibility is a key advantage that organic electronic devices have over conventional inorganic devices. Organic materials intrinsically have mechanical flexibility due to Van der Waals bonding between organic molecules, making ultra-flexible organic devices feasible1,2. Besides the flexibility, compatibility of printing processes is another key advantage of the organic devices. Fabrication processes based on printing have a number of advantages over conventional photolithography. Printable processes can dramatically reduce material waste and manufacturing process steps while lowering manufacturing costs. Moreover, they can be readily scaled to large-area production with high throughput. These features enable low-cost, large-area and flexible device applications, leading to new ways to develop organic electronics in areas such as light-emitting-diodes3, solar cells4, thin-film transistors (TFTs)1,5,6, logic circuits7,8,9 and sensors10,11,12.

The effect of compressive or tensile strain on the performance of organic TFT devices was initially reported by Sekitani et al.1,13,14, followed by other groups2,15,16,17,18,19,20. The authors demonstrated that compressive strain led to an increase while tensile strain led to a decrease in the mobility of organic TFT devices beyond that expected solely from change in the capacitance of the dielectric layer. Recent studies have explored the relationship between the behavior of organic TFT devices under strain and the various factors in the organic TFT devices such as molecular structures of semiconducting materials15,16,19,20, dielectric materials and interfaces between dielectric layers and semiconductor layers18, or contact resistance between source and drain electrodes of organic TFT devices17. However, the gate, source and drain electrodes used in all previous studies were evaporated metals. To achieve flexible organic electronics based on organic TFT devices fabricated by full solution processes, the electrical characteristics must be reproducible in repetition in bending. Reproducible change in on-current in organic TFT device can also be applied to thin-film bending or strain sensors.

Many research groups have studied solution-processed organic TFT devices using various printing methods such as ink-jet7,21,22,23, aerosol-jet24,25, screen26, flexo27 and gravure printing8,28,29. Among them, the fabrication of electrodes from silver nanoparticle inks through inkjet printing process has been the most reported for printed organic TFT devices7,21 because this enables thin and highly conductive electrodes that can reduce operational voltages of printed devices30. However, in contrast to their advantages in terms of high conductivity and low sintering temperature, the printed electrodes from silver nanoparticle ink have a problem in terms of mechanical durability because of a lack of adhesion strength on the substrates31.

In this study, we have fabricated both p-type and n-type organic TFT devices with inkjet-printed silver electrodes from a silver nanoparticle ink and studied the mechanical durability of those devices under tensile strain. By using modified silver nanoparticle ink, we achieved the strong fusion of the printed silver electrodes with the underlying polymer layers, resulting in excellent mechanical durability against the bending strain. The on-current of the organic TFT device clearly decreased as tensile strain increased, which is reproducible even in a bending radius of 4 mm. We found that the change in on-current can be significantly enhanced in shorter channels.

Results

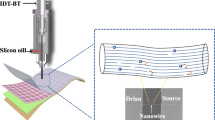

Flexible p-type and n-type organic TFT devices with printed electrodes

Figure 1a schematically shows the structure of the fabricated devices with bottom-gate bottom-contact configurations. Our study dealt with both p-type and n-type organic semiconductor active materials: namely, pentacene as p-type and a benzobis (thiadiazole) (BBT) derivative with trifluoromethylphenyl groups (FPTBBT) as an n-type semiconducting material (figure 1b)32,33. The materials were chosen owing to their relatively high hole and electron mobility. Moreover, pentacene was a standard material for the p-type organic semiconductor and the effects of strain have been well studied by several other groups1,13,14,16,18,20. Thermally cross-linked poly(4-vinyl-phenol) (PVP) was used as the dielectric material. The inkjet-printed silver electrodes from silver nanoparticles dissolved in water-based solvent were used as gate, source and drain electrodes. Photographs of the fabricated devices are shown in figure 1c, 1d and 1e. We can obtain fine source/drain electrodes with line width of 25 μm as shown in Figure 1e.

Flexible organic TFT devices with printed electrodes.

(a) Illustration of an organic TFT device with inkjet-printed silver electrodes under tensile strain. (b) Chemical structure of organic semiconducting materials used in this study. Pentacene as p-type (left) and FPTBBT as n-type (right). (c) A Photograph of the fabricated organic TFT devices installed on human fingers. (d) Optical microscope image of a fabricated TFT and (e) magnified image for channel region.

Adhesion of silver electrodes on the polymer substrates

The adhesion of printed silver electrodes to the underlying cross-linked PVP layers was evaluated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The SEM image of printed silver electrodes is shown in figure 2a. There is no clearance gap between silver electrodes and cross-linked PVP layers, indicating that the printed silver electrodes obtained from the silver nanoparticles exhibited the strong adhesion on polymer layers. Indeed, no cracking/buckling of silver electrodes was observed even after outward bending with a bending radius of 4 mm (1.6% tensile strain) and the electrodes exhibited almost the same surface after strong tensile strain (figure 2b and 2c). In contrast, the silver electrodes obtained from other silver nanoparticles dissolved in a tetradecane (NPS-JL, Harima chemicals) did not exhibit such a strong adhesion property (see supporting Fig. S2). Therefore, the strong durability against the mechanical strain was attributed to the composition of the silver nanoparticle ink used. Indeed, the silver nanoparticle ink used in this study contained 1−5 wt% synthetic resin, which might play an important role as an interfacial binder to the polymer dielectric layer.

Transistor performance

Figure 3 shows the transfer characteristics of both p-type and n-type devices before bending experiments. The source-drain current (IDS) was measured as a function of the gate-source voltage (VGS) at a constant drain-source voltage (VDS) in a nitrogen atmosphere. VDS was set to −20 V for a p-type devices and +20 V for n-type devices. Both pentacene and FPTBBT transistors with printed electrodes exhibited good electrical performances. The estimated field-effect mobility (μ) in the saturation region was 0.12 cm2 V−1 s−1 for both p-type and n-type transistors and on/off ratio was greater than 105. The typical device performances of both p-type and n-type TFT devices in the absence of strain is summarized in Table 1.

Transistor characteristics of both p- and n-type organic TFT devices without strain.

Transfer characteristics of both pentacene-based (blue) and FPTBBT-based (red) organic TFT devices before application of tensile strain. Both p-type and n-type TFTs have almost equal channel length of ~10 μm. Applied source-drain voltages (VDS) for pentacene- and FPTBBT-based devices were −20 V and +20 V, respectively.

Effect of strain on device performance

In this study, the tensile strains were applied to the organic TFT devices with printed silver electrodes. The strains were parallel to the source-drain current paths and the performances of organic TFT devices were evaluated before, during and after the application of strains. The surface strain (S) induced on the active layer was evaluated using the following formula34:

In which dt and ds are the thicknesses of the active layer and the substrate, respectively, η is dt/ds, χ is the ratio between the Young moduli of the active layer and of the substrate (χ = Yl/Ys) and R is the bending radius. Young's modulus of the PEN substrate is 12.2 GPa and the χ is estimated 1.6. Considering that the thickness of substrate (125 μm) is more than two orders of magnitude thicker than the active layer (<1 μm), the surface strain induced on the active layer can be approximated by:

We applied a bending strain with radii ranging from 11 mm down to 4 mm, corresponding to an induced surface strain from 0.57% to 1.6%. All the measurements were carried out from the small deformation regime (large bending radii) and the deformation was constantly increased by reducing the bending radius. The reversibility of the device behavior was checked by measuring the electrical characteristics of the devices in the flat position after each deformation step. For each summary plot, at least two separate devices were tested to ensure reproducibility of the device characteristics.

The electrical behavior of the flexible devices was characterized during the systematic application of tensile strain. Figure 4 shows representative examples of the transfer characteristics in observed electrical characteristics for pentacene and FPTBBT-based devices on cross-linked PVP with channel length of 10 μm. Gate voltage VGS is swept from 20 to −20 V with the application of VDS = −20 V for p-type devices (figure 4a) and VGS is swept from –15 to 20 V with the application of VDS = 20 V for n-type devices (figure 4c). In agreement with previous reports, both p- and n-type devices on polymer dielectrics exhibited a decrease in saturation on-current IDS upon the application of tensile strain13,18,19. The changes in the on-current are −31% for a pentacene-based device and −30% for a FPTBBT-based device at 1.6% tensile strain. We observed a relatively large hysteresis in the transfer characteristics while applying tensile strain, especially in the short channel region. Although the hysteresis became larger during the application of large strain, the transfer characteristics completely returned to the initial state after the tensile strain. Such reproducibility in the device characteristics was also observed for both pentacene and FPTBBT-based devices (Figure 4b and 4d). The on-current IDS value was normalized with initial IDS with application of no strain. The on-current IDS decreased as application of tensile strain was increased and the value returned to its initial value when the application of strain stopped even after the 1.6% strain (R = 4.0 mm). The mechanical flexibility and reproducibility were comparable with previously reported organic TFT devices with evaporated Au electrode13. The excellent mechanical flexibility of our TFT devices with printed silver electrodes is attributed to the strong fusion of the electrodes with the underlying dielectric surfaces. Therefore, these results exhibited the feasibility of applying inkjet-printed electrodes from nanoparticle inks to the flexible electronics.

Electro-mechanical stability of organic TFT devices before, during and after bending.

(a) Transfer characteristics of the pentacene-based TFT device with channel length of 10 μm before, during and after application of 1.6% tensile strain. (b) Saturation source-drain current (IDS) of pentacene-based devices monitored at VDS = VGS = −20 V as a function of measurement number. IDS was normalized from its initial value (without application of strain). (c) Transfer characteristics of the FPTBBT-based TFT device with channel length of 10 μm before, during and after application of 1.6% tensile strain. (b) Saturation source-drain current (IDS) of pentacene-based devices monitored at VDS = VGS = +20 V as a function of measurement number. IDS was normalized from its initial value (without application of strain).

Structural dependence on the strain sensitivity of organic TFT devices

Furthermore, the electrical characterization was performed for devices with different channel width (W) and channel length (L). The channel width dependence is shown in figure 5a and the channel length dependence in figure 5b and 5c. The normalized on-current of pentacene-based devices with the same channel length of 70 μm and with three different channel widths (300, 1000 and 3000 μm) are plotted as a function of tensile strain in figure 5a. The normalized on-current of pentacene-based devices with the same channel width of 1000 μm and with three different channel lengths (150, 70 and 10 μm) are plotted as a function of tensile strain in figure 5b and the same plot of FPTBBT-based devices is shown in figure 5c. Channel width and on-current variation do not correlate, which agrees with the models that explain the current change in organic TFT devices under application of strain34. On the other hand, the strain sensitivity clearly depends on the channel length for both pentacene- and FPTBBT-based devices. As the channel length shortened, the current became more sensitive to the surface strain. The application of 1.6% tensile strain to FPTBBT-based devices with channel lengths of 10 μm and 150 μm results in 31% and 18% changes in the on-current, respectively (Fig. 5b). The same tendency was observed for FPTBBT-based devices. The application of 1.6% tensile strain to FPTBBT-based devices with channel lengths of 10 μm and 150 μm results in a 30% and 14% changes in the on-current, respectively (Fig. 5c). The printed devices exhibited strong channel length dependence on strain sensitivity, which has not been previously reported. The current change is linearly proportional to the application of surface strain for each channel length and each semiconductor material. For each curve, we have also estimated the slope of the sensitivity curve and plotted it as a function of the channel length as shown in figure 5d. There was linear dependence between slope and channel length, at least in the channel length range that we have studied.

Structural dependence on the strain sensitivity of organic TFT devices.

(a) Current variation as a function of tensile strain for pentacene-based TFT devices with different channel width. (b) Current variation as a function of tensile strain for pentacene-based TFT devices with different channel lengths. (c) Current variation as a function of tensile strain for FPTBBT-based TFT devices with different channel lengths. (d) Correlation between sensitivity slopes estimated from fitting curves in (b) and (c) and channel lengths of the TFT devices, showing the device sensitivity clearly depended on the channel lengths of both pentacene-based (blue) and FPTBBT-based (red) organic TFT devices.

Discussion

To understand the mechanism of channel length dependence on strain sensitivity, we here consider the total resistance (RON) between source and drain electrodes:

in which Rch is a channel resistance and RC is a contact resistance. First, we consider the Rch, which is the channel region of organic TFT devices. Several recent studies set out to explore the relationship between the semiconductor molecular structure and the behavior of organic TFT devices under strain. Specifically, pentacene grain size dependence on the strain sensitivity was reported by Cosseddu et al.20. According to this report, the larger the pentacene grain, the larger the strain sensitivity of the organic TFT devices, which was attributed to the hopping transport of charge carrier in the organic semiconductor films35. In our results, although the semiconductor grain sizes in both pentacene and FPTBBT were almost the same in different channel lengths, the tendency of the relationship between the strain sensitivity and the channel length is similar to the experimental results reported by Cosseddu et al. The shorter channel length means the decreased hopping paths between source and drain electrodes. We should also consider the contact resistance. Chen et al. have reported that the RC of pentacene-based organic TFT devices increased slightly during the application of tensile strain17. For shorter channel length, the Rch decreases and the RC becomes dominant in total resistance. Therefore, the increasing of RC might be a possible mechanism for the on-current change in our organic TFT devices under the tensile strain. We are further studying the mechanism of the strain effect on the on-current in printed organic TFT devices.

In conclusion, we have studied the effect of tensile strain on organic thin-film transistors with printed silver electrodes fabricated on a thin plastic substrate. The printed silver electrodes were fabricated from modified nanoparticle ink by ink-jet printing. The fabricated organic TFT devices exhibited excellent electrical performances and reproducible strain dependence of the on-current. This mechanical durability is attributed to strong adhesion between the printed silver electrodes and the underlying polymer layers. Moreover, in both p-type and n-type organic semiconductors, we found that channel length of organic TFT devices plays a significant role in determining sensitivity of transistor characteristics to the applied strain. From these experimental results, we concluded that by properly tuning the channel length, the strain sensitivity in both p-type and n-type organic TFT devices can be controlled easily. The devices with a high strain sensitivity can be made useful for sensing applications by using a short channel length. In contrast, wider channel length is suitable for decreasing their sensitivity to strain.

Methods

Materials

The ink used as printed electrodes in this work was a silver nanoparticle ink in a water-based solvent (JAGLT-01, DIC, Corp. Japan). The ink contained 25–35 wt% silver nanoparticles with an average diameter of 20–40 nm and 1–5wt% synthetic resin. A cross-linked poly-4-vinylphenol (PVP) was used as a planarization layer and gate dielectric layers. PVP (Mw ~ 25000, Sigma Aldrich Co.) and poly(melamine-co-formaldehyde) (Mn ~ 432, 84 wt%, Sigma Aldrich Co.) as a cross-linking agent were mixed in propylene glycol monomethyl ether acetate (PGMEA). The PVP solution was spin-coated onto glass substrates and was thermally cross-linked at temperatures of 150°C for 60 min to form a dielectric layer.

Device fabrication

The devices were fabricated on 125-μm-thick flexible polyethylene naphthalate substrates (PEN). To reduce the surface roughness, our PEN substrates are coated with an 80-nm-thick polymer planarization layer, which is deposited by spin-coating and cured at a temperature of 150°C. The silver nanoparticle ink was patterned with an inkjet printer (Fujifilm Dimatix, DMP2800) onto the planarization layers using a print head with 10 pl nozzles as bottom gate electrodes. The silver nanoparticle ink was printed using a customized waveform. The droplets were deposited with a dot-to-dot spacing of 60 μm. During the inkjet patterning process, the substrate temperature was maintained at 30°C. After the printing, the substrates were stored for 30 min in an environmental test chamber (espec, SH-221) in which the temperature was held at 30°C and relative humidity was held at 95%RH in order to planarize the electrodes30. After the drying process, the substrates were heated at 140°C for 1 hour to sinter the silver nanoparticles. The fabricated silver gate electrodes had uniform thickness of ~100 nm (see supporting figure S1). After these electrodes were formed, a solution of cross-linked PVP was spin-coated and baked to form 350-nm-thick dielectric layers. The silver electrodes were subsequently inkjet printed using a print head with 1 pl nozzles to form the bottom source/drain electrodes. The droplets were deposited with a dot-to-dot spacing of 20 μm. The device geometry was defined by the patterning data of inkjet printing. Finally, a 50-nm-thick pentacene or FPTBBT semiconducting layer was deposited on the source/drain electrodes at a pressure below 5.0 × 10−5 Pa with a deposition rate of 0.2 Å/s. During the deposition, the substrates were not heated nor cooled.

Device characterization

The electrical characteristics of the fabricated TFT devices were measured by using a semiconductor parameter analyzer (Keithley, 4200-SCS). The bending experiments were carried out by wrapping the PEN film around the rod with various radii from 11 to 4 mm. The TFT devices were stressed to the tensile strain parallel to the source/drain electrodes. For each summary plot, at least two separate devices were tested to ensure reproducibility of the device characteristics. All electrical measurements of organic TFT devices were performed in a nitrogen atmosphere to prevent degradation of organic semiconductors induced by oxygen or moisture36. The cross-sectional structure of the printed electrodes was examined by a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (JEOL, 7300F).

References

Sekitani, T. et al. Flexible organic transistors and circuits with extreme bending stability. Nature Mater 9, 1015–1022 (2010).

Yi, H. T. et al. Ultra-flexible solution-processed organic field-effect transistors. Nature Commun 3, 1259 (2012).

Sekitani, T. et al. Stretchable active-matrix organic light-emitting diode display using printable elastic conductors. Nature Mater 8, 494–499 (2009).

Kaltenbrunner, M. et al. Ultrathin and lightweight organic solar cells with high flexibility. Nature Commun 3, 770 (2012).

Khodagholy, D. et al. In vivo recordings of brain activity using organic transistors. Nature Commun 4, 1575 (2013).

Ikawa et al. Simple push coating of polymer thin-film transistors. Nature Commun 3, 1176 (2012).

Ng, T. N. et al. Scalable printed electronics: an organic decoder addressing ferroelectric non-volatile memory. Sci. Rep 2, 585 (2012).

Jung, M. et al. All-Printed and Roll-to-Roll-Printable 13.56-MHz-Operated 1-bit RF Tag on Plastic Foils. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 57, 517–580 (2010).

Myny, K. et al. Organic RFID transponder chip with data rate compatible with electronic product coding. Org. Electron 11, 1176–1179 (2010).

Maiwald, M., Werner, C., Zoellmer, V. & Busse, M. Sens. Actuators, A 162, 198–201 (2010).

Jang, J. Ha, J. & Cho, J. Fabrication of Water-Dispersible Polyaniline-Poly(4- styrenesulfonate) Nanoparticles For Inkjet-Printed Chemical-Sensor Applications. Adv. Mater 19, 1772–1775 (2007).

Lipomi, D. J. et al. Skin-like pressure and strain sensors based on transparent elastic films of carbon nanotubes. Nature Nanotechnol 6, 788–792 (2011).

Sekitani, T. et al. Bending experiment on pentacene field-effect transistors on plastic films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 073511 (2005).

Sekitani, T. et al. Ultraflexible organic field-effect transistors embedded at a neutral strain position. Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 173502 (2005).

Yang, C. et al. Bending-stress-driven phase transitions in pentacene thin films for flexible organic field-effect transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 243305 (2008).

Jedaa, A. & Halik, M. Toward strain resistant flexible organic thin film transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 103309 (2009).

Chen, F.-C. et al. Influence of mechanical strain on the electrical properties of flexible organic thin-film transistors. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 26, 034005 (2011).

Sokolov, A. N. et al. Mechanistic Considerations of Bending-Strain Effectswithin Organic Semiconductors on Polymer Dielectrics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 175–183 (2012).

Niga, A. et al. Strain induced anisotropic effect on electron mobility in C60 based organic field effect transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 083305 (2012).

Cosseddu, P. et al. Continuous tuning of the mechanical sensitivity of Pentacene OTFTs on flexible substrates: From strain sensors to deformable transistors. Org. Electron. 14, 206–211 (2013).

Sekitani, T. et al. Organic transistors manufactured using inkjet technology with subfemtoliter accuracy. Proc. Natl. Anal. Sci. 105, 4976–4980 (2008).

Sirringhaus, H. et al. High-resolution inkjet printing of all-polymer transistor circuits. Science 290, 2123–2126 (2009).

Minemawari, H. et al. Inkjet printing of single-crystal films. Nature 475, 364–367 (2011).

Cho, J. H. et al. Printable ion-gel gate dielectrics for low-voltage polymer thin-film transistors on plastic. Nature Mater 7, 900–906 (2008).

Ha, M. et al. Printed, Sub-3V Digital Circuits on Plastic from Aqueous Carbon Nanotube Inks. ACS Nano 4, 4388–4395 (2010).

Noguchi, Y. et al. Organic-transistor-based flexible pressure sensors using ink-jet-printed electrodes and gate dielectric layers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 253507 (2006).

Yan, H. et al. A high-mobility electron-transporting polymer for printed transistors. Nature 457, 679–686 (2009).

Kang, H. et al. High-Performance Printed Transistors Realized Using Femtoliter Gravure-Printed Sub-10 μm Metallic Nanoparticle Patterns and Highly Uniform Polymer Dielectric and Semiconductor Layers. Adv. Mater. 24, 3065–3069 (2012).

Vornbrock, A. d. l. F. et al. Fully gravure and ink-jet printed high speed pBTTT organic thin film transistors. Org. Electron. 11, 2037–2044 (2011).

Fukuda, K. et al. Profile Control of Inkjet Printed Silver Electrodes and Their Application to Organic Transistors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 3916–3920 (2013).

Joo, S. & Baldwin, D. F. Adhesion mechanisms of nanoparticle silver to substrate materials: identification. Nanotechnology 21, 055204 (2010).

Kono, T. et al. Dithienylbenzobis(thiadiazole) based organic semiconductors with low LUMO levels and narrow energy gaps. Chem. Commun. 46, 3265–3267 (2010).

Fujisaki, Y. et al. Air-stable n-type organic thin-film transistor array and high gain complementary inverter on flexible substrate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 133303 (2010).

Gleskova, H. et al. Electrical response of amorphous silicon thin-film transistors under mechanical strain. J. Appl. Phys. 92, 6224–6229 (2002).

Vissenberg, M. C. J. & Matters, M. Theory of the field-effect mobility in amorphous organic transistors. Phys. Rev. B 57, 12964–12967 (1998).

Ashimine, T. et al. Air Stability of p-Channel Organic Field-Effect Transistors Based on Oligo-p-phenylenevinylene Derivatives. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 47, 1760–1762 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) for their support in this work. We also thank DIC Corporation for providing silver nanoparticle ink and Ube industries, Ltd. for providing FPTBBT. The authors also express their gratitude to Dr. Takuya Morimoto for his contributions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.F., D.K. and S.T. conceived the printed organic TFT concept, processing and structure details. K.F. constructed and characterized the organic TFT devices. K.H., Y.T. and T.M. assisted with device fabrication and characterization. T.S. conducted the SEM observation. K.F. and S.T. wrote the manuscript. K.F. prepared the figures. S.T. supervised the project.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Fukuda, K., Hikichi, K., Sekine, T. et al. Strain sensitivity and durability in p-type and n-type organic thin-film transistors with printed silver electrodes. Sci Rep 3, 2048 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02048

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02048

This article is cited by

-

Flexible organic thin-film transistor immunosensor printed on a one-micron-thick film

Communications Materials (2021)

-

Suppressing molecular vibrations in organic semiconductors by inducing strain

Nature Communications (2016)

-

Printable elastic conductors with a high conductivity for electronic textile applications

Nature Communications (2015)

-

Enhanced performances of organic thin film transistors by dual interfacial modification of dielectric layer

Applied Physics A (2015)

-

Personal electronics printing via tapping mode composite liquid metal ink delivery and adhesion mechanism

Scientific Reports (2014)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.