Abstract

The mid-Piacenzian climate represents the most geologically recent interval of long-term average warmth relative to the last million years and shares similarities with the climate projected for the end of the 21st century. As such, it represents a natural experiment from which we can gain insight into potential climate change impacts, enabling more informed policy decisions for mitigation and adaptation. Here, we present the first systematic comparison of Pliocene sea surface temperature (SST) between an ensemble of eight climate model simulations produced as part of PlioMIP (Pliocene Model Intercomparison Project) with the PRISM (Pliocene Research, Interpretation and Synoptic Mapping) Project mean annual SST field. Our results highlight key regional and dynamic situations where there is discord between the palaeoenvironmental reconstruction and the climate model simulations. These differences have led to improved strategies for both experimental design and temporal refinement of the palaeoenvironmental reconstruction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The deep-time geological record contains responses of the climate system to a wide range of internal and external forcings as well as documentation of intricate short- and long-term feedbacks. While modeling studies of more recent past climate intervals, like the Last Millennium (LM) and the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), provide useful information about the future of our climate system and are being incorporated into the next Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment, palaeoclimate modeling of more ancient time periods have been unable to reproduce some of the key large-scale features associated with periods of extreme global warmth and it is important that we gain a better understanding of such discrepancies. Deep-time climates afford us an opportunity to explore climate sensitivity to a range of atmospheric CO2 levels, to understand how heat is transported during warm climate intervals, to gain insight into the controls on pole-to-equator thermal gradients and to evaluate the stability of ice sheets and the response of sea level during warmer climates. Anthropogenic changes could affect Earth's climate for hundreds to thousands of years, thus analysis and understanding of the most recent deep-time interval of warmth – similar in magnitude to that projected for the end of the 21st century – is relevant to our understanding of future climate and discussion of adaptation and mitigation policies.

The Pliocene Epoch (5.332 Ma to 2.588 Ma) spans an interval of global warmth with high-frequency, low-amplitude variability transitioning to high-frequency, high-amplitude variability associated with the initiation of Northern Hemisphere glaciation. The U.S. Geological Survey's Pliocene Research, Interpretation and Synoptic Mapping (PRISM) group selected for study the most recent interval within the Pliocene (3.264 to 3.025 Ma) known to have temperatures above preindustrial (PI) levels. This interval within the Pliocene, the middle part of the Piacenzian Age, is particularly attractive for palaeoclimate studies because many of the first-order boundary conditions were little different than today: continents and ocean basins were near their present geographic positions and the flora and fauna of the Late Pliocene was in large part identical to present day, allowing for modern analog-type reconstructions of the palaeoenvironment1. Chronology for Piacenzian sequences within deep-sea cores can usually be well-resolved from many magnetobiochronologic events, coupled with an ever-increasing number of orbitally-tuned chronologies2.

The “PRISM interval” has been the focus of two decades of intensive investigations into all aspects of the climate system, resulting in a series of palaeoenvironmental reconstructions: PRISM0, PRISM1, PRISM2 and the current PRISM33,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. PRISM data have been used in a number of climate modeling studies to explore conditions during this last great interval of global warmth31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. A natural evolution of these individual modeling studies was the formation of an organized model intercomparison project for the Pliocene, which includes many of the leading climate models that contribute IPCC simulations.

The Pliocene Model Intercomparison Project (PlioMIP) is a subcomponent of the Palaeoclimate Modelling Intercomparison Project (PMIP40,41;). The initial phase of PlioMIP includes two experiments, both of which focus on the mid-Piacenzian time period equivalent to the PRISM data sets: the first PlioMIP experiment employs atmosphere-only general circulation models and the second utilizes coupled ocean-atmosphere models (see42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54). Both experiments make use of the PRISM3 versions of the boundary condition data sets30.

In this paper we compare initial results of the second PlioMIP experiment using mean annual sea surface temperature (SST) fields derived from eight simulations ( Figure 1 ), with PRISM mean annual SST estimates at each of 100 locations in the PRISM3 marine reconstruction ( Figure 2 ). This comparison is used to document large-scale features of the mid-Piacenzian surface ocean, assess where models and data are in good general agreement and where they are not and also looks at the variability of the multi-model ensemble versus the variability in the palaeodata-based estimates.

Model sea surface temperature anomaly (ΔSST), calculated by subtracting preindustrial from Pliocene sea surface temperature, as simulated by each of the eight PlioMIP models.

(a) CCSM4, (b) COSMOS, (c) GISS-E2-R, (d) HadCM3, (e) IPSL CM5A, (f) MIROC4m, (g) MRI-CGCM2.3, (h) NorESM. Maps created using Panoply v.3.1.3 written by Robert B. Schmunk.

Map showing distribution of PRISM localities, sea surface temperature anomalies (ΔSST), calculated by subtracting modern from Pliocene sea surface temperature and the λ-confidence placed upon each locality estimate (relative size of circle, where larger circles represent greater confidence).

Map created in iMap v.3.5 using World Vector Shoreline (NOAA National Geophysical Data Center, Date Retrieved 4/17/2011, http://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/shorelines/shorelines.html).

Results

Comparison of individual model and data anomalies (ΔMODEL and ΔPRISM, respectively, see “Methods”) on a site-by-site basis identifies a greater range of warming in the reconstructed SST (~10°C spread in ΔPRISM). The models are the most inconsistent with each other and with the PRISM data in the North Atlantic region ( Figure 3 ). This area is, of course, complex given that a myriad of strong feedbacks can affect the region, including changes in sea ice, the Gulf Stream current, Atlantic meridional overturning and even the storm tracks. Similar inconsistency in this region was shown among the general circulation models (GCM's) used in the IPCC 4th assessment55.

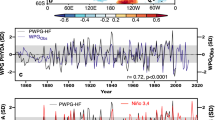

Scatter plot of multi-model-mean anomalies (squares) and PRISM3 data anomalies (large blue circles) by latitude.

Vertical bars on data anomalies represent the variability of warm climate phase within the time-slab at each locality. Small colored circles represent individual model anomalies and show the spread of model estimates about the multi-model-mean. While not directly comparable in terms of the development of the means nor the meaning of variability, this plot provides a first order comparison of the anomalies. Encircled areas are (a) PRISM low latitude sites outside of upwelling areas; (b) North Atlantic coastal sequences and Mediterranean sites; (c) large anomaly PRISM sites from the northern hemisphere. Numbers identify Ocean Drilling Program sites discussed in the text.

Individual models rarely show negative (i.e. Pliocene SST cooler than present day) anomalies. Relative to the data, the multi-model-mean anomaly (ΔMMM) always shows small positive values and exceeds +3°C at only two locations corresponding to core Site 722 on the Arabian Margin and Site 907 in the subarctic North Atlantic ( Figure 3 ).

Negative ΔPRISM values are confined to the tropics and the subtropical North Atlantic ( Figures 2 , 3 ). In the latter (area b in Figure 3 ), these anomalies are isolated to land sections (outcrops) associated with the western boundary current and others in the Mediterranean Sea region. The subtropical estimates are from a combination of planktonic foraminifer, ostracod and Mg/Ca palaeothermometers and represent medium- to high-confidence sites ( Figure 2 ). The tropical sites showing negative ΔPRISM values (area a in Figure 3 ) are located near the equator in all ocean basins and are presently associated with equatorial divergence. Small changes in position of equatorial currents and upwelling cells along coastal regions could explain apparent cooling at these locations.

Other upwelling sites from the Pacific (677, 847, 852, 1236, 1237, 1239), Atlantic (659, 661) and Indian Oceans (722) have some of the largest ΔPRISM values in the low-latitude data set based upon a combination of planktic foraminiferal and alkenone palaeothermometry and show basic agreement between proxies and between ΔPRISM and multi-model-mean anomalies (ΔMMM) ( Figure 3 30; Supplementary information ). Tropical sites in the PRISM3 data set collectively indicate a mean anomaly of +1.08°C. The aforementioned sites have a mean anomaly of +3.21°C. Removal of these sites greatly reduces the magnitude of the mean tropical ΔPRISM (to +0.4°C) and supports the Dowsett et al.28 finding that low latitude SSTs, away from upwelling centers, were indistinguishable from modern conditions.

Documenting the tropical sea surface temperature stability in the Pliocene, particularly given evidence of substantial warming at high latitudes, is of considerable importance for the appraisal of the primary climate drivers for this period. The multi-model ensemble from the IPCC 4th assessment report shows that greenhouse gas forcing of less than a double-CO2 equivalent still yields a tropical warming of more than 1°C by the middle of this century55 while recent Pliocene simulations using the Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) ModelE2-R, a Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5 ) model, found that Pliocene tropical warming exceeded 1°C with as little as 405 ppm CO253. Although the existence of a tropical thermostat mechanism cannot be entirely ruled out given uncertainties in modeled cloud responses, most of the IPCC GCM's would support the lower-end estimates for Pliocene atmospheric CO2. The only locations in the tropics where the PRISM3 data do indicate some warming tend to be in areas of present-day upwelling, so most simulations, which show consistent warming at all longitudes, are still too warm compared with proxies.

A second region of offset between the ΔMMM and ΔPRISM exists in the mid- to high northern latitudes. The majority of sites in Figure 3 (area c) are from the North Atlantic. The extensive warming at high latitudes in the North Atlantic has been repeatedly documented9,27,28,45 and is also seen in terrestrial archives of surface air temperature (e.g.56,57). Mid-latitude sites (410, 548, 552, 606, 607, 608 and 610) are the very highest confidence sites in the PRISM3 data set and the large inter-model spread in this region may be due to the highly variable position of the Gulf Stream—North Atlantic Drift and the resolution of the different models45. However, the magnitude of the warming in the mid- to high-latitude North Atlantic, in both ΔMMM and any ΔMODEL, is small compared to ΔPRISM. While the variability of ΔPRISM (a function of the within-time-slab variability at those localities) and the spread of the individual ΔMODEL results about the ΔMMM overlap in many cases ( Figure 3 ), there is no way to directly compare these uncertainty measures and there exists a consistent offset between data and models.

Four sites in Figure 3 (area c) are outside the North Atlantic. Sites 579 and 580 are located in the North Pacific Kuroshio Extension. Analysis of the diatom assemblages at both sites suggests moderate warming over present day conditions within the PRISM interval8,13. Some but not all PlioMIP simulations pick up this North Pacific warming (relative to PI conditions) ( Figure 1 ). New faunal data from ODP Site 1208, located beneath the Kuroshio Extension, show little change in mean annual temperature relative to present day but suggest greatly reduced seasonality (5°C), with winter temperatures warmer during the Pliocene ( Supplementary material ). This is essentially the same pattern exhibited by the Gulf Stream in the North Atlantic. This reduced seasonality is not demonstrated by PlioMIP simulations.

Sites 1014 and 1021, from the upwelling cell off the west coast of North America, show Pliocene warming (relative to today) documented by both faunal and alkenone palaeothermometry of 6°C–8°C, which is not simulated by any of the models (area c of Figure 3 ). Reed-Sterrett et al.58 suggest the cause may be due to a shoaling thermocline, but an analysis of seasonal vertical temperature profiles from the MIROC4m and GISS-E2-R simulations show no change to the thermocline between Pliocene and PI (preindustrial).

Sites 1236 and 1237 are both situated on the Nazca Ridge. Site 1236 is located just seaward of the main path of the cool, northward flowing Peru-Chile Current while Site 1237 is located near the eastern edge of the current and associated upwelling. Proxy SST data show warmer upwelling conditions during the Pliocene than exist today in the region, analogous to the upwelling region off the Pacific coast of North America ( Figure 2 ). The ΔMMM values do not capture this, but some PlioMIP simulations (GISS-E2-R and HadCM3) do show warmer regional anomalies ( Figure 1 ) and the MIROC4m simulation shows a deepening of the mixed layer during the Pliocene relative to the PI.

Large scale features

Several large-scale first-order features of the Pliocene climate can be found in both data reconstructions and model simulations. Models are generally in good agreement with estimates of Pliocene SST in most regions except the North Atlantic and upwelling regions in the tropics and subtropics ( Figures 1 , 2 ). Despite the complications of variability within the PRISM time slab and the spread shown by the different PlioMIP simulations, there is a fundamental divergence between the two data sets that increases with increasing latitude. This decoupling may stem from a number of sources, including the resolution of the models, differing model parameterizations of subgrid-scale features such as clouds, the highly variable nature of the mid-latitude North Atlantic, or the nature of the Gulf Stream – North Atlantic Drift Current45.

Polar amplification of SSTs is one of the principal signatures of the PRISM data set, with a maximum temperature increase observed in the North Atlantic. However, no such extreme is evident in the MMM data ( Figure 3 ). While individual models show various levels of polar amplification, none are equivalent in magnitude to the PRISM data. Conversely, low-latitude warming is common to all of the PlioMIP simulations, but is not observed in the PRISM data away from upwelling cells. Suggestions that increased oceanic and/or atmospheric heat transport during the Pliocene helped flatten the meridional temperature gradient are not unequivocally supported by the MMM data, because individual model simulations show a wide range of heat transport response59.

Although general ocean surface circulation, based upon global distribution of SSTs, appears to have been broadly similar between the Pliocene and today, patterns of warming seen in the PRISM data in both the North Atlantic and North Pacific could indicate that western boundary currents were more vigorous or that meridional overturning was enhanced. Unfortunately, climate models do not have a consistent Pliocene response with regards to either meridional overturning or ocean heat transport59.

Reduced seasonality, a phenomenon more characteristic of the tropics in the modern, can be documented farther north during the Pliocene based upon analysis of palaeontological assemblages found in coastal regions (e.g. Ref. 60,61,62).

In the Southern Ocean, poleward displacement of palaeo-fronts is documented in the PRISM data by changes in sedimentology, paleontology and productivity14,16 that demonstrate the Pliocene Antarctic Polar Front was as much as 6° latitude further south than today. The corresponding adjustments of isotherms are in close agreement with the PlioMIP simulations, especially when the variability of both is taken into account ( Figure 3 ).

Discussion

Features determined by the analysis of palaeontological and geochemical data as well as output of the PlioMIP simulations document the overall warming of surface waters of the Pliocene ocean.

Large-scale circulation (i.e., the existence of but not necessarily position of subtropical gyres) appears to have been similar in both data reconstructions and model simulations, but the differences in resolution between models and the variability introduced by the PRISM time slab averaging procedures tend to obscure important details. The PlioMIP simulations of mean annual temperature (MAT) do not pick up the magnitude of warming in upwelling regions documented by geochemical and palaeontological proxies in the PRISM data. An initial analysis of seasonal vertical temperature profiles from seven of the eight PlioMIP simulations in the Peru Upwelling region shows a simple temperature offset between PI and Pliocene, but no change to thermocline depth. Only one model, MIROC4m, shows a clearly deeper thermocline and concomitant mixed layer during the Pliocene. Tropical cyclones may play an important role in vertical mixing of the upper ocean63,64, but demonstrating that to be the case for the PlioMIP simulations will require analysis beyond the scope of the current study.

The overall ΔMMM field is in agreement with ΔPRISM values in most regions; however, models do not achieve the level of high-latitude warming seen in the North Atlantic and Arctic data. Reduced sea ice cover no doubt played a significant role in the high latitude warming of the Pliocene. Continued refinement of the model parameterizations and proxy data for Arctic sea ice may improve the agreement between PlioMIP simulations and warmth suggested by marine and terrestrial data.

The mid-latitude North Atlantic is highly variable today and this is reflected in the high variance associated with the ΔMMM in this region. Future experiments aimed at understanding additional forcings and incorporating seasonal rather than mean annual SST may help elucidate the spread in ΔMMM in the mid latitude North Atlantic region.

These PlioMIP simulations, performed with carefully controlled boundary conditions and protocols, point to the need for a more temporally refined data reconstruction with as broad geospatial coverage as possible. The next phase of PlioMIP simulations will be accomplished using a realistic near-modern orbital configuration relevant to future climate discussions65. If the oceanographic record responds strongly to certain orbital periods in certain regions, the time-slab methodology could produce a systematic bias in those regions. Similarly, the time-slab may integrate different seasonality in each measurement within the time-slab. In an attempt to reduce uncertainty, the PRISM4 palaeoenvironmental reconstruction will be correlated to marine isotope stage KM5c representing an order-of-magnitude increase in chronologic resolution66.

The PlioMIP model ensemble comparison to the PRISM3 palaeoenvironmental reconstruction of SST represents the first systematic data-model comparison for the mid-Piacenzian warm period. The differences we identify between proxy data and models, if real, presents a significant challenge in assessing climate sensitivity beyond the current period. Since the Pliocene is an optimal test-bed for models and in the face of current and future warming, it is imperative that the disagreement in amplitude of warming be explored in more detail with a focus on reducing uncertainty in climate proxies as well as uncertainties in the models and their forcings.

Methods

PRISM Reconstruction

The PRISM mean annual temperature verification data set has 100 localities ranging from 77.9° South latitude to 80.4° North latitude and situated in every major ocean basin ( Figure 2 ). Approximately 1/3 of the localities are confined to the Tropics and 1/3 are in the North Atlantic Basin. Twenty percent of the PRISM sites are located in the Southern Ocean. These data are derived primarily from quantitative faunal or floral analyses, augmented where possible with Mg/Ca and alkenone estimates45. The PRISM data have been examined in numerous articles including1,18,30,39,45.

PRISM mean annual SST estimates represent a warm-peak-average, which is defined as the warm phase of climate from the interval between 3.264 Ma and 3.025 Ma at each locality. The use of a time-slab equivalent to ~240 Ky duration introduces variability about the estimated warm phase of SST, expressed as the standard deviation of the warm peak estimates within the time slab at each locality (See Supplementary Information Table S1 ).

Data have been assessed using the λ-confidence scheme45. This provides a measure of confidence based upon chronology, sample density, sample quality and type as well as performance of quantitative method used. λ for included localities ranges from Very High to High to Medium and the percentage of sites corresponding to each level are 29%, 34% and 36% respectively. Figure 2 shows the spatial distribution and confidence of the 100 PRISM localities (see also Supplementary Table S1 ).

Models

The model simulations included in this paper are from CCSM4 (National Center for Atmospheric Research54), GISS-E2-R (NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies53), HadCM3 (Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research52), MIROC4m (Center for Climate System Research, National Institute for Environmental Studies, Frontier Research Center for Global Change44), COSMOS (Alfred Wegner Institute48), IPSL CM5A (Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l'Environnement51), MRI-CGCM2.3 (Meteorological Research Institute and University of Tsukuba50) and NorESM (Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research49). Details of the models are found in Table 1 and in the corresponding publications. The GISS-E2-R, CCSM4 and IPSL CM5A models are the same versions used in IPCC 5th assessment future climate simulations. Coupled ocean-atmosphere model simulations for the PlioMIP experiment will be available from the PMIP3 project https://pmip3.lsce.ipsl.fr/.

In an attempt to standardize the PlioMIP simulations, all models were initialized and run using an identical (to the extent possible) experimental design and protocol ( Table 2 ; see also43). Of the eight models, three (MIROC4m, COSMOS and GISS-E2-R) used the preferred Pliocene boundary conditions, meaning each model's land/sea mask was altered to reflect a 25-meter increase in Pliocene sea level, the existence of ocean in place of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet and the removal of Hudson Bay (which is a result of Pleistocene ice sheet geography).

For each model in the PlioMIP ensemble, the Pliocene simulations were run until the individual modeling groups determined that their models had achieved an equilibrium state; integration times varied from 500 to 1500 years ( Table 1 ). Twelve monthly SST fields were then averaged over the last 30 years of the run to develop a mean annual SST data set. Figure 1 shows the change in SST, Pliocene minus PI, simulated by each of the eight PlioMIP models. In this study, data points representing the PRISM localities are selected directly from the contributed datasets to avoid biases due to interpolation during re-gridding.

Comparison of anomalies

Analysis of the global and regional performance of the eight PlioMIP models is based upon comparison to the multiple proxy SST anomalies documented in45, which are referenced to the mid-20th century calibration of Reynolds and Smith67. We focus on comparing data and model SST anomalies rather than absolutes to avoid biases introduced by the effect of latitude on absolute SST (warmer at lower latitudes and cooler at higher latitudes). Testing the commonality between the anomalies produced by the model and data affords a more accurate test of the model response to Pliocene boundary conditions34,39.

Part of model–data disagreement is related to differences in the control (PI) simulation for each model. We corrected each model anomaly by subtracting a term equivalent to the difference between the mid 20th century calibration used by the palaeontological data and PI conditions39:

where PRISMPLIO is the PRISM3 mean annual SST estimate at each locality (45,68, this paper); RSMODERN is the modern observed temperature at each PRISM locality determined from61; MODELPLIO is the mean annual SST value sampled at each PRISM locality from the model SST field as described above; MODELPREINDUSTRIAL is the mean annual SST value sampled at each PRISM locality from the model control simulation; HadISSTPREINDUSTRIAL is the mean annual SST sampled at each PRISM locality from a PI data set which is a hybrid of observational and modeled data69.

References

Dowsett, H. J. The PRISM palaeoclimate reconstruction and Pliocene sea-surface temperature. In Deep-time perspectives on climate change: marrying the signal from computer models and biological proxies ((eds.Williams, M., Haywood, A.M., Gregory, J. & Schmidt, D. N), pp. 459–480 (Micropalaeontological Society Special Publication, Geological Society of London, 2007).

Wade, B. S., Pearson, P. N., Berggren, W. A. & Pälike, H. Review and revision of Cenozoic tropical planktonic foraminiferal biostratigraphy and calibration to the geomagnetic polarity and astronomical time scale. Earth Sci. Rev. 104, 111–142 (2011).

Dowsett, H. J. & Cronin, T. M. High eustatic sea level during the middle Pliocene: Evidence from the southeastern U.S. Atlantic Coastal Plain. Geology 18, 435–438 (1990).

Cronin, T. M. Pliocene shallow water paleoceanography of the North Atlantic Ocean based on marine ostracodes. Quat. Sci. Rev. 10, 175–188 (1991).

Dowsett, H. J. The development of a long-range foraminifer transfer function and application to Late Pleistocene North Atlantic climatic extremes. Paleoceanography 6, 259–273 (1991).

Dowsett, H. J. & Poore, R. Z. Pliocene sea surface temperatures of the North Atlantic Ocean at 3.0 Ma. Quat. Sci. Rev. 10, 189–204 (1991).

Thompson, R. S. Pliocene environments and climates in the western United States. Quat. Sci. Rev. 10, 115–132 (1991).

Barron, J. A. Pliocene paleoclimatic interpretation of DSDP Site 580 (NW Pacific) using diatoms. Mar. Micropaleontol. 20, 23–44 (1992).

Dowsett, H. J., Cronin, T. M., Poore, R. Z., Thompson, R. S., Whatley, R. C. & Wood, A. M. Micropaleontological evidence for increased meridional heat transport in the North Atlantic Ocean during the Pliocene. Science 258, 1133–1135 (1992).

Cronin, T. M. et al. Microfaunal evidence for elevated Pliocene temperatures in the Arctic Ocean. Paleoceanography 8, 161–173 (1993).

Dowsett, H. et al. Joint investigations of the Middle Pliocene climate I: PRISM paleoenvironmental reconstructions. Global Planet. Change 9, 169–195 (1994).

Willard, D. A. Palynological record from the North Atlantic region at 3 Ma: vegetational distribution during a period of global warmth. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 83, 275–297 (1994).

Barron, J. A. High resolution diatom paleoclimatology of the middle part of the Pliocene of the Northwest Pacific. Proc. Ocean Drill. Program, Sci. Results 145, 43–53 (1995).

Barron, J. A. Diatom constraints on the position of the Antarctic Polar Front in the middle part of the Pliocene. Mar. Micropaleontol. 27, 195–213 (1996).

Cronin, T. M. & Dowsett, H. J. Biotic and oceanographic response to the Pliocene closing of the Central American isthmus. In Evolution and Environment in Tropical America (eds. Jackson, J. B. C., Budd, A. F. & Coates, A. G.), pp. 76–104 (University of Chicago Press, 1996).

Dowsett, H. J., Barron, J. & Poore, H. R. Middle Pliocene sea surface temperatures: a global reconstruction. Mar. Micropaleontol. 27, 13–25 (1996).

Thompson, R. S. & Fleming, R. F. Middle Pliocene vegetation: reconstructions, paleoclimatic inferences and boundary conditions for climate modeling. Mar. Micropaleontol. 27, 27–49 (1996).

Dowsett, H. J. et al. Middle Pliocene Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction: PRISM 2. U.S. Geo. l Surv., Open File Report 99–535, (1999).

Cronin, T. M., Dowsett, H. J., Dwyer, G. S., Baker, P. A. & Chandler, M. A. Mid Pliocene deep-sea bottom-water temperatures based on ostracode Mg/Ca ratios. Mar. Micropaleontol. 54, 249–261 (2005).

Dowsett, H. J., Chandler, M. A., Cronin, T. M. & Dwyer, G. S. Middle Pliocene sea surface temperature variability. Paleoceanography 20, 1–8 (2005).

Dowsett, H. J. & Robinson, M. M. Stratigraphic framework for Pliocene paleoclimate reconstruction: the correlation conundrum. Stratigraphy 3, 53–64 (2006).

Dowsett, H. J. Faunal re-evaluation of Mid-Pliocene conditions in the western equatorial Pacific. Micropaleontology 53, 447–456 (2007).

Dowsett, H. J. & Robinson, M. M. Mid-Pliocene planktic foraminifer assemblage of the North Atlantic Ocean. Micropaleontology 53, 105–126 (2007).

Hill, D. J., Haywood, A. M., Hindmarsh, R. C. A., & Valdes, P. J. Characterizing ice sheets during the Pliocene: evidence from data and models. In Deep time perspectives on climate change: marrying the signals from computer models and biological proxies (eds. Williams, M., Haywood, A. M., Gregory, D., Schmidt, D. N.), pp. 517–538 (Micropalaeontological Society Special Publication, Geological Society of London, 2007).

Robinson, M. M., Dowsett, H. J., Dwyer, G. S. & Lawrence, K. T. Reevaluation of mid-Pliocene North Atlantic sea surface temperatures. Paleoceanography 23 (2008).

Salzmann, U., Haywood, A. M., Lunt, D. J., Valdes, P. J. & Hill, D. J. A new global biome reconstruction and data-model comparison for the Middle Pliocene. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 17, 432–447 (2008).

Dowsett, H. J., Chandler, M. A. & Robinson, M. M. Surface temperatures of the Mid Pliocene North Atlantic Ocean: implications for future climate. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London Ser. A 367, 69–84 (2009).

Dowsett, H. J., Robinson, M. M. & Foley, K. M. Pliocene three-dimensional global ocean temperature reconstruction. Clim. Past 5, 769–783 (2009).

Sohl, L. E. et al. PRISM3/GISS topographic reconstruction. U.S. Geo. l Surv. Data Series 419, 6p (2009).

Dowsett, H. et al. The PRISM3D paleoenvironmental reconstruction. Stratigraphy 7, 123–139 (2010).

Chandler, M. A., Rind, D. & Thompson, R. Joint investigations of the middle Pliocene climate II: GISS GCM Northern Hemisphere results. Global and Planet. Change 9, 197–219 (1994).

Sloan, L. C., Crowley, T. J. & Pollard, D. Modeling of middle Pliocene climate with the NCAR GENESIS general circulation model. Mar. Micropaleontol. 27, 51–61 (1996).

Haywood, A. M., Valdes, P. J. & Sellwood, B. W. Global scale palaeoclimate reconstruction of the middle Pliocene climate using the UKMO GCM: initial results. Global Planet. Change 25, 239–256 (2000).

Haywood, A. & Valdes, P. Modelling Pliocene warmth: contribution of atmosphere, oceans and cryosphere. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 218, 363–377 (2004).

Haywood, A. M. et al. Comparison of mid-Pliocene climate predictions produced by the HadAM3 and GCMAM3 General Circulation Models. Global Planet. Change 66, 208–224 (2009).

Lunt, D. J. et al. Earth system sensitivity inferred from Pliocene modeling and data. Nature Geoscience 3, 60–64 (2010).

Stoll, D. Impacts of Arctic and Equatorial Pacific Sea Surface Temperature Warming on Global Climate, masters thesis,. Alaska Pacific University, Anchorage, AK, 328 p. (2010).

Dolan, A. M. et al. Sensitivity of Pliocene ice sheets to orbital forcing. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 309, 98–110 (2011).

Dowsett, H. J. et al. Sea surface temperatures of the mid-Piacenzian warm period: A comparison of PRISM3 and HadCM3. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 309, 83–91 (2011).

Braconnot, P. et al. Results of PMIP2 coupled simulations of the Mid-Holocene and Last Glacial Maximum – Part 1: experiments and large-scale features. Clim. Past 3, 261–277 (2007).

Braconnot, P. et al. Results of PMIP2 coupled simulations of the Mid-Holocene and Last Glacial Maximum – Part 2: feedbacks with emphasis on the location of the ITCZ and mid- and high latitudes heat budget. Clim. Past 3, 279–296 (2007).

Haywood, A. M. et al. Pliocene Model Intercomparison Project (PlioMIP): experimental design and boundary conditions (Experiment 1). Geosci. Model Dev. 3, 227–242 (2010).

Haywood, A. et al. Pliocene Model Intercomparison Project (PlioMIP): experimental design and boundary conditions (Experiment 2). Geosci. Model Dev. 4, 571–577 (2011).

Chan, W.-L., Abe-Ouchi, A. & Ohgaito, R. Simulating the mid-Pliocene climate with the MIROC general circulation model: experimental design and initial results. Geosci. Model Dev. 4, 1035–1049 (2011).

Dowsett, H. J. et al. Assessing confidence in Pliocene sea surface temperatures to evaluate predictive models. Nature Clim. Change 2, 365–371 (2012).

Koenig, S. J., DeConto, R. & Pollard, D. Pliocene Model Intercomparison Project: implementation strategy and mid-Pliocene Global climatology using GENESIS v3.0 GCM. Geosci. Model Dev. 4, 2577–2603 (2012).

Yan, Q., Zhang, Z., Wang, H., Gao, Y. & Zheng, W. Set-up and preliminary results of mid-Pliocene climate simulations with CAM3.1. Geosci. Model Dev. 4, 3339–3361 (2012).

Stepanek, C. & Lohmann, G. Modelling mid-Pliocene climate with COSMOS. Geosci. Model Dev. 5, 1221–1243 (2012).

Zhang, Z. S. et al. Pre-industrial and mid-Pliocene simulations with NorESM-L. Geosci. Model Dev. 5, 523–533 (2012).

Kamae, Y. & Ueda, H. Mid-Pliocene global climate simulation with MRI CGCM2.3: set-up and initial results of PlioMIP Experiments 1 and 2. Geosci. Model Dev. 5, 793–808 (2012).

Contoux, C., Ramstein, G. & Jost, A. Modelling the mid-Pliocene Warm Period climate with the IPSL coupled model and its atmospheric component LMDZ5A. Geosci. Model Dev. 5, 903–917 (2012).

Bragg, F. J., Lunt, D. J. & Haywood, A. H. Mid-Pliocene climate modeled using the UK Hadley Centre Model: PlioMIP Experiments 1 and 2. Geosci. Model Dev. 5, 1109–1125 (2012).

Chandler, M. A., Sohl, L. E., Jonas, J. E., Dowsett, H. J. & Kelley, M. Simulations of the Mid Pliocene Warm Period using two versions of the NASA/GISS ModelE2-R Coupled Model. Geosci. Model Dev. Disc. 5, 2811–2842 (2012).

Rosenbloom, N. A., Otto-Bliesner, B. L., Brady, E. C. & Lawrence, P. J. Simulating the mid-Pliocene Warm Period with the CCSM4 model. Geosci. Model Dev. Disc. 5, 4269–4303 (2012).

Meehl, G. A. et al. Global Climate Projections. In: Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [Solomon, S., Qin, D., Manning, M., Chen, Z., Marquis, M., Averyt, K. B., Tignor, M. & Miller, H. L. (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA (2007).

Salzmann, U. et al. How well do models reproduce warm terrestrial climates of the past? Nature Climate Change (in revision).

Ballantyne, A. P. et al. Significantly warmer Arctic surface temperatures during the Pliocene indicated by multiple independent proxies. Geology 38, 603–606 (2010).

Reed-Sterrett, C., Dekens, P. S., White, L. D. & Aiello, I. W. Cooling upwelling regions along the California margin during the early Pliocene: evidence for a shoaling thermocline. Stratigraphy 7, 141–150 (2010).

Zhang, K.-S. et al. Mid-pliocene Atlantic meridional overturning circulation not unlike modern? Clim. Past Discuss. 9, 1297–1319 (2013).

Hazel, J. E. Ostracode biostratigraphy of the Yorktown Formation (Upper Miocene and Lower Pliocene) of Virginia and North Carolina. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 704, 13 (1971).

Cronin, T. M. Evolution of marine climates of the U.S. Atlantic Coast during the past four million years. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London Ser. B 318, 661–678 (1988).

Dowsett, H. J. & Wiggs, L. B. Planktonic foraminiferal assemblage of the Yorktown Formation, Virginia, USA. Micropaleontology 38, 75–86 (1992).

Fedorov, A. V., Brierley, C. M. & Emanuel, K. Tropical cyclones and permanent El Niño in the early Pliocene epoch. Nature 463, 1066–1070 (2010).

Sriver, R. L. & Huber, M. Modeled sensitivity of upper thermocline properties to tropical cyclone winds and possible feedbacks on the Hadley circulation. Geophysical Research Letters 37, L08704 (2010).

Haywood, A. M. et al. On the identification of a Pliocene time slice for data-model comparison. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. (in press).

Dowsett, H. et al. The PRISM (Pliocene Palaeoclimate) Reconstruction: Time for a paradigm shift. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. (in press).

Reynolds, R. W. & Smith, T. M. A high-resolution global sea surface temperature climatology. J. Clim. 8, 1571–1583 (1995).

Dowsett, H. J. et al. Mid-Piacenzian mean annual sea surface temperature analysis for data-model comparisons. Stratigraphy 7, 189–198 (2010).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 4407 (2003).

Acknowledgements

HJD, KMF, DKS and MMR acknowledge the continued support of the U.S. Geological Survey Climate and Land Use Change Research and Development Program; HJD, MAC and MMR thank the USGS John Wesley Powell Center for Analysis and Synthesis for support of the PlioMIP initiative; HJD and CRR acknowledge support from the USGS Mendenhall Post-doctoral Fellowship Program; MAC and LES acknowledge support from the NASA Climate Modeling Program and the NASA High-End Computing (HEC) Program through the NASA Center for Climate Simulation (NCCS) at Goddard Space Flight Center. Financial support was provided by grants to US and AMH from the Natural Environment Research Council, NERC (NE/I016287/1); DJL and FJB acknowledge NERC grant NE/H006273/1. BLO and NAR recognize NCAR is sponsored by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and computing resources were provided by the Climate Simulation Laboratory at NCAR's Computational and Information Systems Laboratory (CISL) sponsored by the NSF and other agencies. AMH and AMD acknowledge research leading to these results received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC grant agreement no. 278636. AMD acknowledges the UK Natural Environment Research Council for the provision of a Doctoral Training Grant. CS and GL received funding from AWI and Helmholz through the programmes POLMAR, PACES and REKLIM. WLC and AAO acknowledge financial support from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and computing resources at the Earth Simulator Center, JAMSTEC. This research used samples and/or data provided by the Ocean Drilling Program (ODP). This is a product of the PRISM Project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.D., K.F. and D.S. analyzed the data and DS prepared all illustrations. H.D., K.F., D.S., M.C., L.S., M.B., B.O., F.B., W.C., C.C., A.D., A.H., J.J., A.J., Y.K., G.L., D.L., K.N., A.A., G.R., C.R., M.M., M.R., N.R., U.S., C.S., S.S., H.U., Q.Y. and Z.Z. reviewed the manuscript and contributed simulation or proxy data.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplement

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Dowsett, H., Foley, K., Stoll, D. et al. Sea Surface Temperature of the mid-Piacenzian Ocean: A Data-Model Comparison. Sci Rep 3, 2013 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02013

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02013

This article is cited by

-

Pliocene decoupling of equatorial Pacific temperature and pH gradients

Nature (2021)

-

Atmospheric CO2 during the Mid-Piacenzian Warm Period and the M2 glaciation

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

What can Palaeoclimate Modelling do for you?

Earth Systems and Environment (2019)

-

Atlantic deep water circulation during the last interglacial

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Single-crystalline ZnO sheet Source-Gated Transistors

Scientific Reports (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.