Abstract

Plant-associated bacteria are important for the growth and health of their host, but little is known about its functional diversity and impact on ecosystem functioning. We studied bacterial nitrogen fixation and methane oxidation from indicator Sphagnum mosses in Alpine bogs to test a hypothesis that the plant microbiome contained different functional patterns depending on their functions within the ecosystem. A high abundance and diversity of nitrogenase genes were detected, mostly specific for each Sphagnum. In contrast, methanotrophs formed highly similar patterns despite a high abundance and diversity of methane monooxygenase genes. Our hypothesis was supported by these contrasting functional patterns together with the result that the Sphagnum sporophyte contained a high proportion of specific diazotrophs (45.5%) but no potential methanotrophs. While essential for plant growth under nutrient-limited conditions, nitrogen-fixing bacteria were highly specific and transferred with the sporophyte unlike the ubiquitous methanotrophs which are important for the climate-relevant ecosystem itself.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bog ecosystems, which cover 4 Mill. km2 on Earth, have accumulated more atmospheric carbon than any other terrestrial ecosystem. Due to this extraordinary role in both carbon sequestration and net cooling effects on the global radiation balance, bogs have become essential in maintaining the global climate1,2. Bacterial communities living in bog ecosystems are not only involved in these important ecosystem functions, but are solely responsible for several of them3. For example, bacterial methane oxidation is crucial for the global carbon budget and the Sphagnum-methanotroph consortium acts as a natural filter for methane4,5,6. Additionally, microbial nitrogen fixation enables plant growth under ombrotrophic, nitrogen-limited conditions in bog ecosystems7. The bryophyte genus Sphagnum, which consists of approx. 300 different species, is distributed world-wide and is the dominant component of bog vegetation8. Therefore, Sphagnum mosses have been used globally as an indicator of climate change while their microbial communities are known early indicators of ecosystem disturbances9,10. Recently, we have shown that living Sphagnum mosses are colonised in high abundances with specific microorganisms7,11,12,13, yet the composition, spatial distribution and transmission of the bacterial communities are well-known, less is known about the functional diversity within the microbiome.

Plant specificity of associated bacteria and fungi is a well-established phenomenon14,15. Interestingly, in a study by Germida & Siciliano16, the evolutionary relationship in plant–microbe interactions was determined: old wheat cultivars were colonised by phylogenetically diverse rhizobacteria, whereas the rhizosphere of modern cultivars was dominated by fast-growing Proteobacteria. Bryophytes were the first land plants. Especially Sphagnum-dominated bog ecosystems belong to the oldest vegetation forms with more or less constant conditions for thousands of years. As a result, bog plant and microbial communities were co-exposed over long evolutionary time and developed multiple interactions. Correspondingly, an extremely high impact of the Sphagnum species was found on the structure of the microbial communities, which are transferred directly from the sporophyte (within the sporangium capsule) to the gametophyte and vice versa13. Despite this specificity, methane-oxidizing bacteria on different Sphagnum species were highly similar5,17. Our hypothesis for this study was that different microbial groups can show either specific or redundant pattern according to their function within the ecosystem.

We designed a new approach combining qPCR, pyrosequencing and network analyses of functional genes to get insights into functional bacterial diversity of Sphagnum mosses and its effects on ecosystem functioning in three different Alpine bogs in Austria. While the quantitative and structural analysis of the microbiome is well-established, pyrosequencing and bioinformatic analyses of functional gene amplicon libraries are still restricted to a few, mainly methodical studies18,19,20. We analysed key microbial genes encoding nitrogenase reductase (nifH) and particulate methane monooxygenase (pmoA) to find differences between bacterial communities of two dominant and cosmopolitan Sphagnum species, S. magellanicum and S. fallax. S. magellanicum BRID. (section Sphagnum) is typical for strongly acidic, oligotrophic and ombrotrophic habitats, whereas S. fallax H. KLINGGR. (section Cuspidata) grows in weakly acidic, more mesotrophic environments influenced by minerotrophic groundwater8. Network analysis using Cytoscape 2.8 software21 was applied to identify which functional taxa are generalists (broadly distributed across all habitats) or specialists (restricted to certain habitats but locally abundant) according to Barberán et al.22.

Results

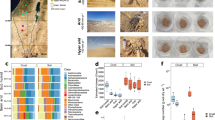

Abundances of functional bacterial genes in Sphagnum mosses

Quantification of nifH and pmoA genes resulted in high copy numbers for both moss species (Fig. 1). In regards to nitrogen fixation, higher nifH gene copy numbers were detected for S. fallax (log10 7.0 ± 0.2 to log10 7.4 ± 0.3 copies g−1 fresh weight (FW)) in comparison to the S. magellanicum samples (log10 6.8 ± 0.1 to log10 7.0 ± 0.2 copies g−1 FW). A statistically significant difference was detected between Sphagnum spp. in sampling sites Rotmoos and Pürgschachen Moor (P = 0.004; 0.012) and in comparing copy numbers between species over all sampling sites (P = 0.0006). In regards to methane oxidation, pmoA gene copy numbers were also slightly higher for S. fallax (log10 6.3 ± 0.2 to log10 6.6 ± 0.3 copies g−1 FW) than for S. magellanicum samples (log10 6.0 ± 0.3 to log10 6.1 ± 0.2 copies g−1 FW). A statistically significant difference was shown between Sphagna from Pürgschachen Moor (P = 0.024) and testing copy numbers over all sampling sites (P = 0.002).

Abundance of the bacterial nifH and pmoA genes in Sphagnum gametophytes detected by qPCR.

The log abundances of nifH (a) and pmoA (b) gene copies per g fresh weight (FW) of S. magellanicum (black bars) and S. fallax (grey bars) in three sampling sites. Error bars indicate confidence intervals. Asterisks denote significant differences between moss species (*, P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01).

Deep insight into functional microbial diversity using pyrosequencing

The pyrosequencing libraries of the nifH and pmoA genes were analysed for high-throughput characterisation of diazotrophic and methanotrophic bacteria in Sphagna. The nitrogenase gene libraries were rarefied as shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. Richness estimation of the normalised datasets revealed that pyrosequencing effort attained 58.2–76.5% of the estimated richness for the clusters of 92% similarity (Table 1). The NifH clusters of 96 and 100% reflected 42.0–60.6 and 15.0–24.1% of the estimated richness, respectively. Nitrogenase diversity estimated by the Shannon diversity index (H′) was higher for S. fallax than for S. magellanicum for all sampling sites (Table 1).

BLAST analysis of the NifH composition revealed an immense dominance of the amplicons related to Proteobacteria. The nifH deduced amino acid sequences were assigned to different classes and were prevailed by Alphaproteobacteria. Representative sequences of the most frequent NifH clusters showed ≥95% similarity to the NifH sequences of Bradyrhizobium, Azorhizobium, Beijerinckia, Rhodopseudomonas, Rhizobium and Methylobacterium species. Detected Betaproteobacteria were presented by the genus Burkholderia followed by Cupriavidus and Rhodoferax (≥97% similarity). NifH sequences related to Gammaproteobacteria were assigned to Stenotrophomonas and Pseudomonas genera (95–98% sequence similarity). The minor NifH clusters contained sequences 95–100% similar to Deltaproteobacteria (Geobacter spp.). A sub-dominant portion of amplicons was affiliated with cyanobacterial genera Anabaena, Tolypothrix and Aphanizomenon (≥95% similarity). According to the NCBI database, minor part of the retrieved sequences showed 98–100% similarity to the NifH sequences from methanotrophic bacteria of genera Methylocystis, Methylomonas, Methylocella and Methylosinus.

Rarefaction analysis of the particulate methane monooxygenase gene libraries resulted in similar saturation profiles for all Sphagnum samples with the exception of S. fallax from Pürgschachen Moor (Supplementary Fig. S1). While normalised datasets reached complete saturation at 82% similarity (Table 1), the PmoA clusters of 92 and 96% covered 17.4–24.7% and 46.3–94.5% of estimated richness, respectively. Except for the FP library (S. fallax, Pürgschachen Moor), methane monooxygenase diversity as estimated by the Shannon index was highly similar between Sphagnum spp. (Table 1).

PmoA diversity explored by BLAST analysis comprised type I and type II methanotrophs in an equal abundance ratio. Representative sequences of the PmoA clusters showed 89–98% sequence similarity to genus Methylomonas (type Ia), while the other group of PmoA sequences had 95–99% similarity to Methylocystis spp. (type II). Interestingly, the pmoA gene library of S. fallax from Pürgschachen Moor consisted solely of the amplicons related to the type II methanotrophs.

Comparison of the functional microbial patterns

Nitrogenase gene (nifH) amplicon libraries were compared using abundance-based Sørensen indices corrected for unseen species23. By applying 96% and 92% cut-offs, amplicon libraries formed S. fallax- and S. magellanicum-specific patterns at 55% and 67% similarity levels respectively (Fig. 2). According to the statistical analysis, 23 out of 118 examined NifH clusters (92%) showed a significant difference (P < 0.05) between Sphagnum spp. Network analysis demonstrated the distribution of the specific NifH patterns between S. fallax and S. magellanicum among all sampling sites (Fig. 3). The S. magellanicum-abundant NifH pattern consisted of sequence clusters affiliated with Methylobacterium sp., Beijerinckiaceae, Beijerinckia spp. and Azorhizobium spp. Conversely, the S. fallax-abundant NifH pattern contained clusters assigned to Burkholderia spp., Rhodoferax sp., Cupriavidus sp. and Bradyrhizobium sp.

Unweighted pair group method with average linkages (UPGMA) analysis of nifH and pmoA gene amplicon libraries.

UPGMA dendrograms were constructed using Chao's corrected Sørensen matrices for NifH (a–c) and PmoA (d–f) datasets of S. magellanicum (M) and S. fallax (F) from three sampling sites (R = Rotmoos, W = Wasenmoos, P = Pürgschachen Moor). Similarity cut-offs applied for clustering of datasets are indicated for each dendrogram correspondingly.

Profile clustering network analysis of the microbial NifH and PmoA clusters in Sphagnum samples.

NifH clusters of 92% similarity (a) and PmoA clusters of 93% similarity (b) were examined for two-fold abundance increase in Sphagnum spp. in three sampling sites. According to the results, single clusters were connected to profiles SM (abundant in S. magellanicum), SF (abundant in S. fallax) and/or COM (no change). The width of the node connections defines the number of sampling sites. The size of each node is proportional to the cluster abundance. The colour and label of the nodes specify phylogenetic and taxonomic affiliation of the clusters correspondingly. NifH network shows only clusters statistically different (P < 0.05) between Sphagnum species.

Comparison of the pmoA gene amplicon libraries revealed a high similarity between both bryophytes. With applied cut-offs, S. fallax- and S. magellanicum-originated libraries formed a common pattern of 99% similarity (Fig. 2). Statistical analysis of 23 PmoA clusters (93%) resulted in a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) between moss species for 2 minor clusters. Network analysis revealed a general distribution of the PmoA pattern among Sphagna in all sampling sites (Fig. 3).

Linking taxonomic and functional microbial patterns of sporophyte and gametophyte

The 16S rRNA gene amplicon library of the S. fallax sporophyte generated with universal bacterial primers was analysed to reveal cross-links between taxonomic and functional diversity of the moss microbiome. Rarefaction analysis revealed complete saturation of the sporophyte library at the phyla level (Supplementary Fig. S2). At the species and genera level, a pyrosequencing survey achieved 54.8% and 65.2% of estimated richness, respectively (Table 1).

Classified 16S rRNA gene sequences were distributed among five bacterial phyla: over-dominant Proteobacteria (82.8%) followed by sub-dominant Bacteroidetes (9.4%) and Acidobacteria (7.5%) with only a few sequences affiliated to Actinobacteria and OP10. Bacteria associated with sporophyte were assigned to 37 genera (Fig. 4). According to the NCBI database, 12 detected genera (45.5% of the total diversity) comprise bacteria known for nitrogen fixation. The most dominant nifH-holding taxa were presented by Burkholderia (35.1%), Herbaspirillum (2.6%), Pseudomonas (2.0%), Sphingobacterium (1.9%), Leptothrix (1.2%) and Rhizobium (1.0%). Obtained results coincide with the network analysis: NifH clusters related to Burkholderia spp. formed a specific pattern in S. fallax gametophytes. Interestingly, no methanotrophic bacteria were detected within the sporophyte library.

Taxonomic classification of bacteria associated with S. fallax sporophyte.

16S rRNA gene amplicon library (FSR) was classified at genus level with confidence threshold of 50%. Only classified reads were designated (1003). Pie chart (a) represents relative abundance of the dominant genera. Genera not reaching 1% of relative abundance are assembled in the group Other and are shown in detail as a bar chart (b). Genera depicted with asterisks comprise bacteria carrying nifH gene (according to the NCBI database).

Discussion

Plant survival in nutrient-poor or ombrotrophic bog ecosystems depends on their associated bacteria. We examined two important functional groups of Sphagnum-associated bacteria in three Alpine Sphagnum-dominated bog ecosystems and found two distinct ecological patterns: diazotrophic specialists and methanotrophic generalists. In order to investigate the reasons underlying these different patterns detected by pyrosequencing of bacterial nifH and pmoA genes and corresponding network analyses, our hypothesis for this study was that different microbial groups can show specific or redundant patterns according to their function within the ecosystem. The obtained results support this hypothesis.

Nitrogen acquisition is an essential process for all forms of life, including plants24. Under nutrient-depleted conditions, bacterial nitrogen fixation could serve as the only source of N enabling plant germination and growth25,26. The investigated moss species harbored highly specific nitrogen fixers which are essential for Sphagnum growth. Previous research revealed the transfer of the core microbiome from the moss sporophyte to the gametophyte13. In this study, the microbiome of the Sphagnum sporophyte contained a high proportion (45.5%) and diversity of potential nitrogen-fixing bacteria that could explain the specificity of diazotrophic communities associated with matured plants. These facts underline the importance of bacterial nitrogen fixation for Sphagnum mosses themselves.

In contrast to nitrogen fixation, methane oxidation is an important function for the whole bog ecosystem, but less essential for each member of the higher plant and moss community. Correspondingly, we detected 99% similar PmoA patterns associated with the moss gametophytes and an absence of potential methanotrophic bacteria in the sporophyte-transferred microbiome. This phenomenon can be explained as follows. Although moss-associated methanotrophs can supply the host plants with carbon dioxide4, peat mosses acquire carbon primarily from autotrophically fixed atmospheric CO2 and their carbon source is not restricted to microbial activity. On the other site, methanotrophic bacteria are able to fix atmospheric N227 and could also serve as nitrogen source for Sphagna. However, diazotrophic growth of methanotrophs is strongly sensitive to oxygen and therefore the maximum population density and activity in N-depleted bog ecosystems are located below the water table28. The investigated species S. fallax and S. magellanicum belong both to the group of non-submerged species and therefore this overlap is unlikely. Finally, methanotrophs are dispersed by water within the bog ecosystem and thus their composition was already described as non-specific and ubiquitous5,17.

In our study, we applied high-throughput molecular approaches - pyrosequencing and quantitative PCR - to resolve the functional diversity of the Sphagnum microbiome. However, pyrosequencing and bioinformatic analysis of functional gene amplicon libraries are restricted to few currently published works18,19,20 and is therefore necessary to critically assess data and conclusions. Primer selection played a crucial role for detection and comparison of diazotrophic and methanotrophic microbial patterns with pyrosequencing. A set of applied nifH gene-specific primers was shown to cover the broadest spectrum of nifH sequences29. Conversely, existing pmoA-targeting primers displayed only modest coverage, which should be considered during data analyses. Thus, the unveiled particulate methane monooxygenase diversity contained type II and type Ia methanotrophic bacteria which were ubiquitously detected through all moisture conditions, while type Ib methanotrophs specific to habitats with a high water table remained uncovered30. Interestingly, neither pmoA nor nifH gene pyrosequencing libraries contained type II methanotrophs of the genus Methylocapsa. Namely, Methylocapsa acidiphila was originally isolated from the Russian Sphagnum peat bog and exhibited acidophilic lifestyle31. When tested in silico, Methylocapsa spp. were out-selected by the pmoA gene-targeting primers and remained undetected by the pyrosequencing of the nifH gene amplicons. Furthermore, focusing on the pmoA gene diversity, we disregarded methanotrophic bacteria which use only soluble methane monooxygenase encoded by mmoX gene such as genera Methylocella and Methyloferula detected in bog environments3. In addition, a much higher diversity of methanotrophs is predicted to exist and newly described methanotrophic bacteria must be implemented in the primer design32. In spite of the partial diversity uncovered, detected Methylocystis and Methylosinus genera were shown to be dominant methanotrophs associated with living Sphagna19,33.

In this study, we observed statistically greater abundances of the diazotrophic specialists as well as methanotrophic generalists in S. fallax than in S. magellanicum. This difference underlines the influence of a-biotic parameters that shape the microbiome13,34. S. magellanicum lives in strongly acidic, oligotrophic and ombrotrophic habitats, whereas S. fallax grows in weakly acidic, more mesotrophic environments influenced by minerotrophic groundwater. As a result, S. magellanicum would need more nitrogen to survive than S. fallax. Life in the ombrotrophic bog bulks is very limited, not only due to lack of nutrients also because of the extreme pH (2–4.5), which is a main driver of microbial communities35 and can explain these differences.

Recently, a high specificity of the structure of the plant-associated microbiome at cultivar level was described15. Our study shows that different functional groups are characterised by a different degree of specificity. For the first time, we found evidence for different functional pattern of plant-associated bacteria. Moreover, we found that their ecosystem function is an important driver of functional diversity.

Methods

Sampling design

To analyse differences between two Sphagnum species, S. magellanicum Brid. (section Sphagnum) and S. fallax H. Klinggr. (section Cuspidata) were selected. Both bryophytes belong to the typical and cosmopolitan vegetation in peat bogs8. Adult gametophytes of moss species were sampled in three different natural Alpine bogs in Austria in September 2009 (Supplementary Table S1). From each of the three investigated bogs, four single replicates in at least 10 m distance per Sphagnum species consisting of 15–20 plantlets were collected and stored separately. The living green parts of the plantlets were placed into sterile plastic bags and transported to the laboratory. S. fallax plants forming sporophytes were solely detected in the Rotmoos bog. Enclosed spore capsules of S. fallax were collected and processed separately. In general, S. magellanicum sporophytes are rarely found.

Isolation of total-community DNA

The microbial fraction associated with moss gametophytes was extracted as previously described13. In short, 5 g of plant material were physically disrupted with a sterile pestle and mortar and resuspended in 10 ml of 0.85% NaCl. 2 ml of suspension were then centrifuged (16500 g, 20 min, 4°C). The obtained pellet was used for isolation of the total-community DNA with the FastDNA® SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA). For mechanical lysis, the cells were homogenised twice in a FastPrep® FP120 Instrument (Qbiogene, BIO101, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 30 s at a speed of 5.0 m sec−1 and treated according to the  protocol. Extraction of bacteria from the surface-sterilised sporophyte of S. fallax was carried out as previously described13. Final aliquots of the total-community DNA were further subjected to PCR-based approaches.

protocol. Extraction of bacteria from the surface-sterilised sporophyte of S. fallax was carried out as previously described13. Final aliquots of the total-community DNA were further subjected to PCR-based approaches.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Quantification of the microbial nifH and pmoA genes was conducted with primer pairs nifH-F/nifH-R and A189f/A621r as referenced36,37. Standards were generated by cloning the respective gene fragments from Erwinia carotovora subsp. atroseptica SCRI1043 and Methylosinus sporium ATCC35069 into the pGEM-T® Easy Vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Cloned fragments were re-amplified with vector-specific primers USP (5′-GTAAAACGACAACCAGT-3′) and RSP (5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGACC-3′) and purified using Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). To eliminate inhibitory effects of co-extracted substances, total-community DNA was diluted to 1:25 (data of preliminary experiments). Target genes were amplified using KAPA SYBR® FAST qPCR Kit (Kapa Biosystems, Woburn, MA, USA) in 10 μl reaction mixtures. Each measurement was performed two times in three independent runs on the Rotor-Gene 6000 (Corbett Research, Mortlake, Australia). Specificity of amplicons was confirmed by melting-curve analyses and gel-electrophoresis of the PCR products. Concentrations were calculated to copy number per g fresh weight and statistically analysed.

Deep-sequencing and bioinformatic processing

The diversity of methane-oxidizing and nitrogen-fixing bacteria associated with Sphagna was thoroughly investigated using a barcoded pyrosequencing approach. The total-community DNA of Sphagnum gametophytes was amplified with the set of nifH gene-specific primers nifH3/nifH4, nifH1/nifH2 with the nested approach38 and pmoA gene-specific primers A189f/A650r19,39,40 using Taq-&Go™ Ready-to-use PCR Mix (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA). Total-community DNA of the S. fallax sporophyte was studied using universal bacterial primers 799f/1492r41,42. Duplicate PCR products from all templates were purified with Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Amplicons derived from the same Sphagnum sp. and sampling site were pooled together and subjected to the pyrosequencing using the Roche/454 GS FLX and FLX+ Titanium platforms executed by LGC Genomics (Berlin, Germany) and GATC Biotech (Konstanz, Germany) correspondingly.

Amplicon libraries of the nifH and pmoA microbial genes were studied using the FunGene Pipeline of RDP server (http://fungene.cme.msu.edu/FunGenePipeline/)43 with the parameters previously described18,20. For the nifH amplicon libraries, primer sequences were trimmed and reads of low quality and shorter than 200 bp were removed. Filtered reads were translated into amino acid sequences and clipped at 60 aa. Further analyses were carried out on amino acid sequences. Rarefaction curves were generated for clusters with 100%, 96% and 92% similarity cut-offs. To calculate richness estimates and diversity indices, datasets were normalised to the same number of sequences using an in-house developed Perl script (10-times random re-sampling followed by subset formation). NifH clusters of 92% similarity (≥10 sequences) were further explored by statistical and network analyses. Representative sequences for each cluster were aligned using the NCBI algorithm TBLASTN.

The amplicon libraries of the pmoA gene were similarly processed. Trimmed reads of high quality and ≥400 bp were translated into amino acid sequences and clipped at 131 common positions. Rarefaction curves were obtained for clusters of 100%, 93% and 82% similarity. Richness estimates and diversity indices were calculated for the datasets normalised to the identical sequencing depth. The PmoA clusters of 93% similarity (≥10 sequences) were characterised through alignment of the representative sequences and subjected to further analyses.

The 16S rRNA gene amplicon library of the S. fallax sporophyte was pre-processed as previously described12,13. Rarefaction analysis and richness and diversity estimation were performed using tools from RDP Pipeline (http://pyro.cme.msu.edu)43. Phylotype clusters were defined with 97%, 95% and 80% similarity cut-offs corresponding to the levels of the species, genera and phyla, respectively44,45. Read classification was performed using the UCLUST pipeline integrated into the web interface SnoWMAn version 1.11 (https://epona.genome.tugraz.at/snowman/)46 with 50% confidence threshold.

Statistics

The nifH and pmoA gene copy numbers were statistically analysed using PASW Statistics 18 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The data was tested for normal distribution by Q-Q plots and the Shapiro-Wilk test. Homogeneity of variances was checked using the Levene test. The significance of the difference between S. magellanicum and S. fallax in each sampling site and for all sampling sites was calculated using a t-test with independent samples.

To detect differentially abundant microbial clusters associated with Sphagna, NifH (92%) and PmoA (93%) clusters with ≥10 sequences were studied using Metastats web interface47. Populations of S. fallax (MR, MW, MP datasets) and S. magellanicum (FR, FW, FP datasets) were examined using a combination of the nonparametric t-test, exact Fisher's test and the false discovery rate with 1000 permutations. P-values were determined for each cluster correspondingly.

Profile clustering network analysis

Network analysis was performed to visualise functional microbial patterns and to compare their abundance between Sphagnum species across the three sampling sites48. NifH (92%) and PmoA (93%) clusters with a cumulative read change of ≥5 sequences were examined for an abundance ratio between S. magellanicum and S. fallax in each sampling site. If the ratio of values exceeded 2.0, the clusters were assigned to the specific profile (abundant in S. magellanicum or S. fallax). To refine NifH network analysis, we considered only clusters statistically different between Sphagnum species (P < 0.05). Visualization of the network was performed with the open source software Cytoscape 2.821.

References

Strack, M. Peatlands and climate change (International Peat Society, 2008).

Dise, N. B. Environmental science. Peatland response to global change. Science 326, 810–811 (2009).

Dedysh, S. N. Cultivating uncultured bacteria from northern wetlands: knowledge gained and remaining gaps. Front. Microbio. 2, 184, 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00184 (2011).

Raghoebarsing, A. A. et al. Methanotrophic symbionts provide carbon for photosynthesis in peat bogs. Nature 436, 1153–1156 (2005).

Larmola, T. et al. The role of Sphagnum mosses in the methane cycling of a boreal mire. Ecology 91, 2356–2365 (2010).

Tveit, A., Schwacke, R., Svenning, M. M. & Urich, T. Organic carbon transformations in high-Arctic peat soils: key functions and microorganisms. ISME J. 7, 299–311 (2013).

Opelt, K. et al. Investigations of the structure and function of bacterial communities associated with Sphagnum mosses. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 2795–2809 (2007a).

Daniels, R. E. & Eddy, A. 1985. Handbook of European Sphagna. Institute of Terrestrial Ecology. (Cambrian News, 1985).

Whinam, J. & Copson, G. Sphagnum moss: an indicator of climate change in the sub-Antarctic. Polar Rec. 42, 43–49 (2006).

Jassey, V. E., Gilbert, D., Binet, P., Toussaint, M. L. & Chiapusio, G. Effect of a temperature gradient on Sphagnum fallax and its associated living microbial communities: a study under controlled conditions. Can. J. Microbiol. 57, 226–235 (2011).

Opelt, K., Berg, C. & Berg, G. The bryophyte genus Sphagnum is a reservoir for powerful and extraordinary antagonists and potentially facultative human pathogens. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 61, 38–53 (2007b).

Bragina, A. et al. Similar diversity of Alphaproteobacteria and nitrogenase gene amplicons on two related Sphagnum mosses. Front. Microbio. 2, 275, 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00275 (2011).

Bragina, A. et al. Sphagnum mosses harbour highly specific bacterial diversity during their whole lifecycle. ISME J. 6, 802–813 (2012).

Berg, G. & Smalla, K. Plant species and soil type cooperatively shape the structure and function of microbial communities in the rhizosphere. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 68, 1–13 (2009).

Bulgarelli, D. et al. Revealing structure and assembly cues for Arabidopsis root-inhabiting bacterial microbiota. Nature 488, 91–95 (2012).

Germida, J. & Siciliano, S. Taxonomic diversity of bacteria associated with roots of modern, recent and ancient wheat cultivars. Biol. Fert. Soils 33, 410–415 (2001).

Putkinen, A. et al. Water dispersal of methanotrophic bacteria maintains functional methane oxidation in Sphagnum mosses. Front. Microbio. 3, 15, 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00015 (2012).

Farnelid, H. et al. Nitrogenase gene amplicons from global marine surface waters are dominated by genes of non-cyanobacteria. PLoS ONE 6, e19223, 10.1371/journal.pone.0019223 (2011).

Kip, N. et al. Ultra-deep pyrosequencing of pmoA amplicons confirms the prevalence of Methylomonas and Methylocystis in Sphagnum mosses from Dutch peat bog. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 3, 667–673 (2011).

Lüke, C. & Frenzel, P. Potential of pmoA amplicon pyrosequencing for methanotroph diversity studies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 6305–6309 (2011).

Smoot, M. E., Ono, K., Ruscheinski, J., Wang, P. L. & Ideker, T. Cytoscape 2.8: new features for data integration and network visualization. Bioinformatics 27, 431–432 (2011).

Barberán, A., Bates, S. T., Casamayor, E. O. & Fierer, N. Using network analysis to explore co-occurrence patterns in soil microbial communities. ISME J. 6, 343–351 (2012).

Chao, A., Chazdon, R. L., Colwell, R. K. & Shen, T. J. Abundance-based similarity indices and their estimation when there are unseen species in samples. Biometrics 62, 361–371 (2006).

Kraiser, T., Gras, D. E., Gutiérrez, A. G., González, B. & Gutiérrez, R. A. A holistic view on nitrogen acquisition in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 1455–1466 (2011).

Tauro, T. P., Nezomba, H., Mtambanengwe, F. & Mapfumo, P. Germination, field establishment patterns and nitrogen fixation of indigenous legumes on nutrient-depleted soils. Symbiosis 48, 92–101 (2009).

Moir, J. W. Nitrogen cycling in bacteria: Molecular analysis. (Caister Academic Press, 2011).

Auman, A. J., Speake, C. C. & Lidstrom, M. E. nifH sequences and nitrogen fixation in type I and type II methanotrophs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 4009–4016 (2001).

Dedysh, S. N., Ricke, P. & Liesack, W. NifH and NifD phylogenies: an evolutionary basis for understanding nitrogen fixation capabilities of methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiology 150, 1301–1313 (2004).

Gaby, J. C. & Buckley, D. H. A comprehensive evaluation of PCR primers to amplify the nifH gene of nitrogenase. PLoS ONE 7, e42149, 10.1371/journal.pone.0042149 (2012).

Siljanen, H. M. et al. Hydrology is reflected in functioning and community composition of methanotrophs in the littoral wetland of a boreal lake. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 75, 430–445 (2011).

Dedysh, S. N. et al. Methylocapsa acidiphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel methane-oxidizing and dinitrogen-fixing acidophilic bacterium from Sphagnum bog. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micr. 52, 251–261 (2002).

Luesken, F. A. et al. pmoA-primers for detection of anaerobic methanotrophs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 3877–3880 (2011).

Kip, N. et al. Methanotrophic activity and diversity in different Sphagnum magellanicum dominated habitats in the southernmost peat bogs of Patagonia. Biogeosciences 9, 47–55 (2012).

Opelt, K., Berg, C., Schönmann, S., Eberl, L. & Berg, G. High specificity but contrasting biodiversity of Sphagnum-associated bacterial and plant communities in bog ecosystems independent of the geographical region. ISME J. 1, 502–516 (2007).

Rousk, J. et al. Soil bacterial and fungal communities across a pH gradient in an arable soil. ISME J. 4, 1340–1351 (2010).

Hai, B. et al. Quantification of key genes steering the microbial nitrogen cycle in the rhizosphere of sorghum cultivars in tropical agroecosystems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 4993–5000 (2009).

Tuomivirta, T. T., Yrjälä, K. & Fritze, H. Quantitative PCR of pmoA using novel reverse primer correlates with potential methane oxidation in Finnish fen. Res. Microbiol. 160, 751–756 (2009).

Zehr, J. P. & Turner, P. J. In: Methods in Microbiology, ed. 271–285 (Academic Press, 2001).

Holmes, A. J., Costello, A., Lidstrom, M. E. & Murrell, J. C. Evidence that particulate methane monooxygenase and ammonia monooxygenase may be evolutionary related. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 132, 203–208 (1995).

Bourne, D. G., McDonald, I. R. & Murrell, J. C. Comparison of pmoA PCR primer sets as tools for investigating methanotroph diversity in three Danish soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 3802–3809 (2001).

Lane, D. J. In: Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics, ed. 115–175 (Wiley, 1991).

Chelius, M. K. & Triplett, E. W. The diversity of archaea and bacteria in association with roots of Zea mays L. Microb. Ecol. 41, 252–263 (2001).

Cole, J. R. et al. The ribosomal database project: improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D141–D145 (2009).

White, J. R. et al. Alignment and clustering of phylogenetic markers – implications for microbial diversity study. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 152, 10.1186/1471-2105-11-152 (2010).

Will, C. et al. Horizon-specific bacterial community composition of German grassland soils, as revealed by pyrosequencing-based analysis of 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 6751–6759 (2010).

Stocker, S. et al. SnoWMAn: High-throughput phylotyping, analysis and comparison of microbial communities. Under revision (2011).

White, J. R., Nagarajan, N. & Pop, M. Statistical methods for detecting deferentially abundant features in clinical metagenomic samples. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000352, 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000352 (2009).

Grube, M., Köberl, M., Lackner, S., Berg, C. & Berg, G. Host-parasite interaction and microbiome response: effects of fungal infections on the bacterial community of the Alpine lichen Solorina crocea. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 82, 472–481 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Benli Chai (East Lansing) for excellent cooperation using and improving the FunGene Pipeline and Stefan Lackner (Graz) for helpful discussions on network analysis. Furthermore, we would also like to thank Meg Starcher (Graz/Washington) for English revision of the manuscript. We would also like to acknowledge Vladimir Chebotar and Andrey Shcherbakov (St. Petersburg) for good cooperation in the joint project, especially during the sampling time. This study was supported by Austrian Science Foundation (FWF grant no. E-1653100183) to G.B.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.B., C.B., A.B. designed and performed the experiments, analysed the data. H.M. gave technical support and conceptual advice. D.M. developed new bioinformatic tools. All authors discussed results and implications. A.B. and G.B. wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript at all stages.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Bragina, A., Berg, C., Müller, H. et al. Insights into functional bacterial diversity and its effects on Alpine bog ecosystem functioning. Sci Rep 3, 1955 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01955

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01955

This article is cited by

-

Composition and Function of Bacterial Communities of Bryophytes and Their Underlying Sediments in the Dajiuhu Peatland, Central China

Journal of Earth Science (2023)

-

Novel metabolic interactions and environmental conditions mediate the boreal peatmoss-cyanobacteria mutualism

The ISME Journal (2022)

-

Too much of a good thing? Inorganic nitrogen (N) inhibits moss-associated N2 fixation but organic N can promote it

Biogeochemistry (2022)

-

Bog ecosystems as a playground for plant–microbe coevolution: bryophytes and vascular plants harbour functionally adapted bacteria

Microbiome (2021)

-

Environmental patterns of brown moss- and Sphagnum-associated microbial communities

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.