Abstract

Increased atmospheric CO2 concentrations lead to decreased pH and carbonate availability in the ocean (Ocean Acidification, OA). Carbon dioxide seeps serve as ‘windows into the future’ to study the ability of marine invertebrates to acclimatise to OA. We studied benthic foraminifera in sediments from shallow volcanic CO2 seeps in Papua New Guinea. Conditions follow a gradient from present day pH/pCO2 to those expected past 2100. We show that foraminiferal densities and diversity declined steeply with increasing pCO2. Foraminifera were almost absent at sites with pH < 7.9 (>700 μatm pCO2). Symbiont-bearing species did not exhibit reduced vulnerability to extinction at <7.9 pH. Non-calcifying taxa declined less steeply along pCO2 gradients, but were also absent in samples at pH < 7.9. Data suggest the possibility of an OA induced ecological extinction of shallow tropical benthic foraminifera by 2100; similar to extinctions observed in the geological past.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations are nearly 40% above pre-industrial levels and are likely to double by the end of this century1. The absorption of atmospheric carbon dioxide by the oceans decreases pH and carbonate availability2 (‘ocean acidification’, OA). These changes can have deleterious effects on marine invertebrates relying on calcification3,4. Volcanic carbon dioxide seeps5,6 can provide proxies to investigate how calcifying marine organisms acclimatise to exposure to OA. Recent studies of CO2 seeps in shallow temperate and tropical marine ecosystems provided the first data on ecosystem-wide changes caused by OA. These studies documented negative effects of OA on calcifying organisms including corals, echinoderms, gastropods, crustose coralline algae and foraminifera5,6,7,8. In contrast, seagrasses, microalgae or non-calcifying macroalgae either benefitted from increased DIC availability or were resilient to pH/DIC changes5,6,7,8,9,10. At the tropical seeps, coral diversity and structural complexity sharply dropped as pCO2 values approached those expected for the end of this century, while coral cover remained unaffected5.

Benthic foraminifera are a diverse group of large protists (up to 2 cm) that have an organic wall, form carbonate tests though biotic calcification or form tests through agglutination of sediment particles. Tropical foraminifera have high calcification rates and are important contributors to carbonate sediments. The tests of calcifying foraminifera are made of either high- or low magnesium calcite (Mg-calcite), while only a few taxa produce aragonite11. High Mg-calcite is the most soluble form of carbonate and organisms producing high-Mg-calcite are considered particularly vulnerable to OA.

Many tropical foraminiferal taxa live in symbiosis with unicellular dinoflagellates, diatoms, green or red algae or retaining chloroplasts from algal food and are thus mixotrophic, while the remainder are predominantly heterotrophic. Several studies have investigated the effects of OA on benthic foraminifera. Experiments using CO2 to manipulate seawater chemistry on four species of diatom-bearing and two dinoflagellate-bearing species found only weak effects of reduced pH/increased pCO212,13, while other studies found stronger effects14,15. A previous field study around a Mediterranean CO2 seep showed that assemblages shifted from calcifying to agglutinate assemblages and diversity declined at pH ~ 7.87. Also, a foraminiferal species living on seagrasses was absent near tropical CO2 seeps at pH < 7.9 where its calcification was reduced4.

Here, we investigate changes in the diverse assemblages of tropical sediment-associated foraminifera along natural CO2 gradients at CO2 seeps in Milne Bay Province, Papua New Guinea (PNG). Assemblages can be considered acclimatized to high CO2 through long-term exposure (>70 years of volcanic seep activity) to pCO2 concentrations as predicted for later this century (490 to >1370 μatm pCO216). Previous studies have suggested that CO2 uptake by photosynthesis elevates pH in the diffusive boundary layer and may thus provide partial protection against OA to mixotrophic groups17,18. The seeps investigated here are located within the ‘Coral Triangle’, an area of six Central Pacific nations that harbour the most diverse marine ecosystems on earth. The high diversity of the PNG assemblages, consisting of both mixotrophic and heterotrophic taxa (Supplementary Table 1), provided a unique opportunity to investigate the relative vulnerabilities to OA across taxonomic and trophic groupings.

Results

Seawater chemistry contrasted strongly between the 12 control and seep sites, with mean values generally ranging from 8.08 to 7.52 pH units and 369 to 11603 μatm pCO2, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). One extreme site assumed pH values of ~7.0 and pCO2 values of >5000 μatm pCO2. With the exception of that site, calcite and aragonite saturation values at each location remained well above 1.0 (the value at which carbonate theoretically dissolves). Mean total alkalinity was 2326 μmol kg−1 (N = 134, SD = 66). Thus 95% of all alkalinity values were between 2197 and 2456 μmol kg−1, a range we used together with the pH measurements from all stations to calculate pCO2 concentrations (Fig. 1 A). These pH measurements showed a good correlation to the long term averages for the 12 core sites (Supplementary Table 2, R2 = 0.89, p < 0.0001).

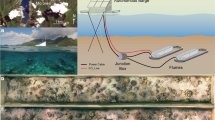

Changes in sediments and foraminiferal assemblages along pCO2 gradients at the three CO2 seep and three control sites.

Relationships between pHTotal and pCO2 in the seawater (A), the total inorganic carbon of the sediment (B), total foraminiferal density (C) and total diversity (D). The black lines represents linear model fits, grey areas mark ranges (A): assuming highest and lowest measured temperatures and alkalinity), or 95% confidence intervals (B–D). Dashed lines demark predicted CO2 concentrations and corresponding pH values at the end of this century following representative concentration pathways21 (RCP 2.6: pCO2 = 421 μatm; SCP 6.0 to 4.5: pCO2 = 670 μatm; RCP 8.5: pCO2 = 936 μatm). Blue symbols in (A) represent pH and pCO2 concentrations at the main stations presented in Supplementary table 2. Other colours represent the sample locations (Upa-Upasina: green, Esa'Ala: orange, Dobu: red).

Concentrations of inorganic carbon (IC) in the sediments declined significantly with declining pH (linear model, Fig. 1 B, Table 1), from nearly 100% carbonate sediment (IC = 12%) at ambient pH to nearly zero in most samples below pH 7.7. Sediment organic carbon and nitrogen were unrelated to pH (C: R2 = 0.01, p = 0.58; N: R2 < 0.01, p = 0.99). Data found were on a low level typical for coral reef sediments (organic-C: average: 0.28%, SD = 0.21%; N: average = 0.03%, SD = 0.02%). Because of the low level of organic content, the fact that values do not differ between seeps and control areas and that most foraminifera investigated are epibenthic or epiphytic it is unlikely that dissolution driven by interstitial respiratory processes contributed to the observed patterns.

Water collected over the benthos showed no significant (ANOVA, p = 0.1509) difference in the concentration of arsenic between control (mean = 1.62 μg L−1, SD = 0.08 μg L−1) and high (mean = 1.88 μg L−1, SD = 0.50 μg L−1) CO2 sites and values were in the range on typical marine samples (1–2 μg L−1). Sediments had slightly higher arsenic concentrations directly at the main seeps (which emit almost pure CO25;) compared with the control sites (Seeps: mean = 12.8 mg kg−1, SD = 9.8 mg kg−1, N = 4; Controls: 7.1 mg kg−1, SD = 1.8 mg kg−1, N = 5), most likely reflecting the low carbonate content in the seep sediments. Concentrations in sediments were low compared to those at other volcanic vents (e.g., Ambitle Island, PNG: range: 52–33,200 mg kg−119). In addition, diverse and abundant foraminiferal communities have been described under sediment and water column arsenic concentrations >10 times those reported here20. Arsenic and ten further metal contaminants measured in water above the benthos showed no differences between seep and non-seep sites and were in ranges expected in pristine seawater (Supplementary Table 3). Temperature loggers recorded only 0.3°C warmer conditions on the benthic surfaces at the seeps compared to the control sites and annual temperature extremes also only varied by this amount (Seeps: average: 29.6°C, maximum and minimum: 32.2°C and 26.8°C; Controls: 29.3°C, maximum and minimum: 31.8°C and 26.7°C), again in contrast to some other seep sites (e.g., Ambitle surface sediments: seep temperatures: 45–98°C, vs. control site: 30.2°C19).

Foraminifera were abundant at control sites (mean densities: 93 individuals g−1 sediment, SD = 54 individuals g−1 sediment). Densities declined steeply with increasing pCO2 (Table 1, Fig. 1 C) and foraminifera were almost absent at pCO2 conditions predicted for the end of this century under all but the most optimistic emission scenarios (RCP2.6, peak at 440 μatm pCO2,21; Fig. 1 A, C). The density of mixotrophic and heterotrophic taxa decreased at the same rate and their slopes of decline did not differ significantly (Table 1). In other words, both groups followed the same trajectory towards extinction with increasing pCO2. The slope of decline was less steep for agglutinate compared to calcifying taxa; however, this group was overall rare (1.0% of the assemblage at ambient pH, SD = 1.4%) and they were also absent in any samples at pH < 7.9.

A total of 49 foraminiferal taxa were detected in the 50 sediment samples (Supplementary Table 1). Total foraminiferal diversity also declined with increasing pCO2 (Table 1, Fig. 1 D).

The comparisons of the slopes for diversity directly mirrored those of densities: there was no significant difference in the rate of diversity loss between mixotrophic and heterotrophic taxa (Table 1). The loss of diversity was significantly slower for agglutinate taxa, but only three taxa were recorded.

Additional dive searches (>5 h total) at Upa-Upasina for living large mixotrophic foraminifera on algal, seagrass and coral rubble substrata revealed that several species can be readily found at the control site (Amphistegina spp., Calcarina spp., Heterostegina depressa, Marginopora vertebralis), whereas none could be detected at locations with reduced (<~7.9) pH values.

A permutational multivariate analysis of variance (Permanova) indicated significant differences in foraminiferal assemblage composition between the three sampling locations (Supplementary Table 4). The main difference between locations was that mixotrophic species were dominant at one of the locations (Upa-Upasina) and heterotrophic species dominated at the other two locations (Supplementary Table 5). A distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) showed that the relative contribution of most taxa to the foraminiferal assemblage did not change along the pCO2 gradient (Supplementary Fig. 1). pCO2 explained only a small (5.2%) albeit significant proportion of the variation in relative abundances between samples (Pseudo-F = 2.41, p = 0.0133). This confirmed that most taxa disappeared at a similar rate with increasing pCO2. Exceptions were three species (two Elphidium spp. and Amphistegina lessonii) which increased slightly in relative importance at intermediate pCO2 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Closer inspection of the three samples that had intermediate foraminiferal densities at <7.9–8.0 pH (Fig. 1) showed that most of their foraminifera were Amphistegina spp. and Elphidium spp., i.e., taxa that appeared to increase in relative importance with elevated pCO2. However, many of these specimens had a corroded or pitted appearance (Fig. 2). This appearance was not detected in any of the control samples in Milne Bay at present-day pCO2 conditions, or in sediment core slices >1000 yr of age from the Great Barrier Reef (22, Fig. 2). The pitted appearance is similar to that observed in another Amphistegina species under experimental CO2 increase23.

Scanning Electron Micrographs of Amphistegina spp.

(A–B) illustrate specimens with corroded and pitted appearance, as found in many foraminifera from sample locations with pH 7.9–8.0. The example shown is from "Esa'Ala elevated pCO2" (see Table 1), where average pCO2 over 15 samples was 444 μatm. (C–D) represent a sample from the control location near the Esa'Ala seep (average pCO2: 369 μatm, Table 1). (E–F) show a sample from a sediment core slice of the Great Barrier Reef (Edward 7, 130–140 cm depth), carbon dated as 1361 years before present (68.5% probability interval: 1157–156422,). This sample illustrates that the test corrosion observed near CO2 vents is not part of the ‘normal’ taphonomic process.

Discussion

Foraminiferal density and diversity at the control sites in PNG were high and similar to those observed on the Great Barrier Reef22,24 or other sites in PNG25. Our data show no sign of acclimation by benthic foraminifera to high pCO2, although a proportion of genotypes will have lived near the seeps for many generations (their reproduction is partly non-dispersive asexual, as well as through gametes). Our analyses along the pH/pCO2 gradients around the seeps in PNG suggested that all common tropical foraminiferal species will likely be ecologically extinct at the CO2 conditions predicted for the year 2100, except under the most optimistic scenario. However, that scenario is unlikely, requiring immediate drastic emission cuts and negative net emission (i.e. carbon sequestration) in the second half of this century26.

Several mass extinctions of deep sea benthic foraminifera occurred in the geological past, most of which were linked to increased pCO2 and/or temperature27,28, but some geological studies from shallow reef environments also observed increased foraminiferal dominance when corals became rare29. None of these previous extinctions were as severe as the ecological or even taxonomic extinction in shallow carbonate areas we predict. Previous natural pCO2 increases occurred one to two orders of magnitude slower and were associated with less reduced calcite or aragonite saturation states than the anthropogenic increases presently observed28.

Contrary to our initial hypothesis, no shift towards mixotrophic taxa was observed. We assumed that photosymbiont-bearing taxa might be less vulnerable to OA because carbon fixation may increase pH in their diffusive boundary layer18; this can lead to pH differences of >0.8 units between day and night17,18. A recent study in foraminifera, however, showed that these increases cannot compensate for decreased pH in ambient water30. We hypothesized that agglutinate taxa which do not rely on calcification might replace calcifying species. In our study, density and diversity of agglutinate taxa declined less steeply than calcifying taxa. However, agglutinate taxa were too rare to fill the niches vacated by calcifying taxa.

Carbonate sediments at seeps disappeared at calcite or aragonite saturation states >1.0 (Supplementary Table 2). Previous experiments have shown test dissolution and corrosion in temperate heterotrophic foraminifera at >900 μatm pCO231; although one species still calcified at 1900 pCO232. However, our electron microscopy and sediment inorganic carbon data showed corrosion of foraminifera at 7.9–8.0 pH and absence of biogenic carbonate accumulation, suggesting that carbonate dissolution began at pCO2 levels of ~450 μatm. Dissolution of foraminifera and sediment was previously observed under elevated pCO2 and can start at aragonite saturations states above 333,34. Indeed, most biogenic carbonates dissolved at much higher saturation values than predicted from abiotic carbonates35. Thus, in addition to the described direct ecological impacts, the loss of benthic foraminifera, together with dissolution and loss of biogenesis of carbonate by other organisms under near-future pCO2 conditions may also have far-reaching ecological flow-on effects.

Methods

50 sediment samples were collected during two expeditions to the seep sites5 in August 2010 and April 2011. Samples were collected at various distances from the three seeps (Esa'Ala, Upa-Upasina, Dobu Island) and their control sites5. Samples of the top 1 cm sediment were sourced from 4 to 15 m depth. At each site, three haphazard samples were taken and pooled into one sample.

For the estimation of foraminiferal abundances, sediments were rinsed over a 63 μm sieve. After drying (>24 h, 60°C), all foraminifera were collected from subsamples until 200 specimens per sample were obtained. This yield could not be achieved for some of the samples collected near the seep sites. In that case, all available sediment was searched. We collected only intact specimens which showed no sign of degradation and little damage (‘optimally preserved’, sensu36) under the dissection microscope at 25× magnification. These specimens are regarded as a good representation of the present-day (time averaged over the last few years) biocoenosis36. Taxa were determined under a dissection microscope, following Uthicke et al. 201024. The dry weights of both sediment and foraminifera were determined to calculate foraminiferal densities. A subsample of foraminifera was observed via Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) in order to identify signs of corrosion. Organic matter was removed by incubating the tests in 2% NaClO for 1 h at 60°C. Foraminiferal tests were then dehydrated in 100% ethanol, mounted on SEM stubs and sputter-coated with gold and visualized on a JEOL JSM-5410LV scanning electron microscope.

A subsample of the sediment prior to rinsing and sieving was dried and ground for total carbon and nitrogen determination. Samples were analyzed on a Truspec C/N Analyser (Leco). After acidification (2 M hydrochloric acid), organic carbon in the sediments was measured using a TOC-V Analyser (Shimadzu, equipped with a SSM-5000A Solid Sample Module).

Arsenic concentrations in sediments were determined on acid digested (HNO3/HClO4) subsamples, by Hydride Generation Atomic Absorption Spectrometry using a Thermo SOLAAR M Atomic absorption spectrometer. To assess surface sediment temperatures, six temperature loggers (TidbiT v2, Hobo Data loggers) were deployed on the substrata of all seep and control sites for 363 days (April 2011 to April 2012; one logger from Upa-Upasina failed and data are reported for 5 loggers only).

Seawater carbonate chemistry data were based on those presented in5, complemented by additional samples from April 2011 following the same procedures and based on total alkalinity and dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) measurements. Arsenic and 10 common heavy metal pollutants were analysed from triplicate (unless marked otherwise in Supplementary Table 3) samples from each of the seep and control sites on an ICP-MS using an octapole reaction system to limit matrix interferences. Samples for these analyses were collected in two opposite seasons, in May and December 2012.

Linear models were used to test for relationships between average pH and the dependent sediment chemistry variables and foraminiferal total density and diversity and density and diversity of individual groups. Models were fitted after log transformation (natural logarithm) of the dependent variable. The initial models included depth and pH, but depth was removed from the final models because it did not explain a significant amount of variation for any of the parameters (Supplementary Table 6). Slopes of two groups were compared by adding ‘groups’, ‘pH’ and their interaction term into the model and accepting slopes as homogenous when the interaction term was non-significant.

Distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) was used to investigate patterns in assemblage composition across samples. Initial permutation tests showed that depth had no effect of assemblage patterns (Pseudo-F = 1.62, p = 0.0958), but location (Esa'Ala, Upa-Upasina and Dobu Island) affected distributions (Pseudo-F = 6.57, p < 0.0001). These location effects were removed (partialled out) because they were not of interest in the context of our study. The mean pH value for each sample was converted to pCO2 and used as environmental variable. DbRDA was conducted on a Bray-Curtis distance matrix of fourth-root transformed relative abundance data.

Single-factor permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was used to investigate the significance of differences in assemblage composition between sample locations. PERMANOVA post-hoc tests presented here were based on 10,000 permutations, using type III sums of squares and permutation of residuals under a reduced model. Subsequent to PERMANOVA, similarity percentage (SIMPER) was used to investigate which taxa contributed most to between-group differences. DbRDA and linear model analyses were performed in R. PERMANOVA and SIMPER analyses were conducted in Primer 6.0.

References

Feely, R. A., Doney, S. C. & Cooley, S. R. Ocean acidification: Present conditions and future changes in a high-CO2 world. Oceanography 22, 39–47 (2009).

Feely, R. A. et al. Impact of anthropogenic CO2 on the CaCO3 system in the oceans. Science 305, 362–366 (2004).

Ries, J. B. Skeletal mineralogy in a high-CO2 world. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 403, 54–64 (2011).

Uthicke, S. & Fabricius, K. Productivity gains do not compensate for reduced calcification under near-future ocean acidification in the photosynthetic benthic foraminifera Marginopora vertebralis. Global Change Biology 18, 2781–2791 (2012).

Fabricius, K. E. et al. Losers and winners in coral reefs acclimatized to elevated carbon dioxide concentrations. Nature Climate Change 1, 165–169 (2011).

Hall-Spencer, J. M. et al. Volcanic carbon dioxide vents show ecosystem effects of ocean acidification. Nature 454, 96–99 (2008).

Dias, B. B., Hart, M. B., Smart, C. W. & Hall-Spencer, J. M. Modern seawater acidification: the response of foraminifera to high-CO2 conditions in the Mediterranean Sea. Journal of Geological Society 167, 843 (2010).

Martin, S. et al. Effects of naturally acidified seawater on seagrass calcareous epibionts. Biology Letters 4, 689 (2008).

Porzio, L., Buia, M. C. & Hall-Spencer, J. M. Effects of ocean acidification on macroalgal communities. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 400, 278–287 (2011).

Johnson, V. R. et al. Responses of marine benthic microalgae to elevated CO2 . Marine Biology online first, 1–12, DOI 10.1007/s00227-011-1840-2 (2011).

Blackmon, P. D. & Todd, R. Mineralogy of some foraminifera as related to their classification and ecology. Journal of Paleontology, 1–15 (1959).

Fujita, K., Hikami, M., Suzuki, A., Kuroyanagi, A. & Kawahata, H. Effects of ocean acidification on calcification of symbiont-bearing reef foraminifera. Biogeosciences Discuss. 8, 1809–1829 (2011).

Vogel, N. & Uthicke, S. Calcification and photobiology in symbiont-bearing benthic foraminifera and responses to a high CO2 environment. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 424, 15–24 (2012).

Kuroyanagi, A., Kawahata, H., Suzuki, A., Fujita, K. & Irie, T. Impacts of ocean acidification on large benthic foraminifers: Results from laboratory experiments. Marine Micropaleontology 7, 190–195 (2009).

Reymond, C. E., Lloyd, A., Kline, D. I., Dove, S. G. & Pandolfi, J. M. Decline in growth of foraminifer Marginopora rossi under eutrophication and ocean acidification scenarios. Global Change Biology 19, 291–302, 10.1111/gcb.12035 (2013).

Moss, R. H. et al. The next generation of scenarios for climate change research and assessment. Nature 463, 747–756 (2010).

De Beer, D. & Larkum, A. Photosynthesis and calcification in the calcifying algae Halimeda discoidea studied with microsensors. Plant, Cell & Environment 24, 1209–1217 (2001).

Koehler-Rink, S. & Kuehl, M. Microsensor studies of photosynthesis and respiration in larger symbiotic foraminifera. I. The physico-chemical microenvironment of Marginopora vertebralis, Amphistegina lobifera and Amphisorus hemprichii. Mar. Biol. 137, 473–486 (2000).

Price, R. E. & Pichler, T. Distribution, speciation and bioavailability of arsenic in a shallow-water submarine hydrothermal system, Tutum Bay, Ambitle Island, PNG. Chemical geology 224, 122–135 (2005).

McCloskey, B. Foraminiferal responses to arsenic in a shallow-water hydrothermal system in Papua New Guinea and in the laboratory. PhD thesis, University of Miami (2009).

Meinshausen, M. et al. The RCP greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions from 1765 to 2300. Climatic Change 109, 213–241 (2011).

Uthicke, S., Patel, F. & Ditchburn, R. Elevated land runoff after European settlement perturbs persistent foraminiferal assemblages on the Great Barrier Reef. Ecology 93, 111–121 (2012).

McIntyre-Wressnig, A., Bernhard, J. M., McCorkle, D. C. & Hallock, P. Non-lethal effects of ocean acidification on the symbiont-bearing benthic foraminifer Amphistegina gibbosa. MEPS 472, 45–60 (2013).

Uthicke, S., Thompson, A. & Schaffelke, B. Effectiveness of benthic foraminiferal and coral assemblages as water quality indicators on inshore reefs of the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Coral Reefs 29, 209–225 (2010).

Langer, M. R. & Lipps, J. H. Foraminiferal distribution and diversity, Madang reef and lagoon, Papua New Guinea. Coral Reefs 22, 143–154 (2003).

Arora, V. K. et al. Carbon emission limits required to satisfy future representative concentration pathways of greenhouse gases. Geophys. Res. Lett 38, L05805 (2011).

Zachos, J. C. et al. Rapid acidification of the ocean during the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum. Science 308, 1611–1615 (2005).

Hönisch, B. et al. The Geological Record of Ocean Acidification. Science 335, 1058–1063 (2012).

Scheibner, C. & Speijer, R. P. Late Paleocene-early Eocene Tethyan carbonate platform evolution: A response to long- and short-term paleoclimatic change. Earth-Science Reviews 90, 71–102 (2008).

Glas, M. S., Fabricius, K. E., de Beer, D. & Uthicke, S. The O2, pH and Ca2+ microenvironment of benthic foraminifera in a high CO2 World. PLoS ONE 7, e50010 (2012).

Haynert, K., Schönfeld, J., Riebesell, U. & Polovodova, I. Biometry and dissolution features of the benthic foraminifer Ammonia aomoriensis at high pCO2 . Mar Ecol Prog Ser 432, 53–67 (2011).

Dissard, D., Nehrke, G., Reichart, G. J. & Bijma, J. Impact of seawater pCO2 on calcification and Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca ratios in benthic foraminifera calcite: results from culturing experiments with Ammonia tepida. Biogeosciences 81, 81–93 (2011).

Yamamoto, S. et al. Threshold of carbonate saturation state determined by CO2 control experiment. Biogeosciences 9, 1441–1450 (2012).

Yates, K. & Halley, R. CO32− concentration and pCO2 thresholds for calcification and dissolution on the Molokai reef flat, Hawaii. Biogeosciences Discussions 3, 123–154 (2006).

Morse, J. W., Andersson, A. J. & Mackenzie, F. T. Initial responses of carbonate-rich shelf sediments to rising atmospheric pCO2 and. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 70, 5814–5830 (2006).

Yordanova, E. K. & Hohenegger, J. Taphonomy of larger Foraminifera: relationships between living individuals and empty tests on flat reef slopes (Sesoko Island, Japan). Facies 46, 169–204 (2002).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Councillors of the Dobu RLLG and the Traditional Owners of the seep sites for allowing us to survey their reefs. We are grateful for comments by R. Albright on an earlier draft. The research was funded by the Australian Institute of Marine Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.U. conducted and designed experiments, analysed data and wrote the MS. P.M. Analysed data and foraminiferal samples and contributed to the writing. K.F. conceived the overall seep project and contributed to writing and analysis.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplements

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Uthicke, S., Momigliano, P. & Fabricius, K. High risk of extinction of benthic foraminifera in this century due to ocean acidification. Sci Rep 3, 1769 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01769

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01769

This article is cited by

-

Climate change and infectious disease: a review of evidence and research trends

Infectious Diseases of Poverty (2023)

-

Triassic/Jurassic bivalve biodiversity dynamics: biotic versus abiotic factors

Arabian Journal of Geosciences (2023)

-

Impact of submarine karst sulfur springs on benthic foraminiferal assemblage in sediment of northern Adriatic Sea

Journal of Soils and Sediments (2023)

-

The coral reef-dwelling Peneroplis spp. shows calcification recovery to ocean acidification conditions

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Amphistegina lobifera foraminifera are excellent bioindicators of heat stress on high latitude Red Sea reefs

Coral Reefs (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.