Abstract

Here, we used a biologically contained Ebola virus system to characterize the spatio-temporal distribution of Ebola virus proteins and RNA during virus replication. We found that viral nucleoprotein (NP), the polymerase cofactor VP35, the major matrix protein VP40, the transcription activator VP30 and the minor matrix protein VP24 were distributed in cytoplasmic inclusions. These inclusions enlarged near the nucleus, became smaller pieces and subsequently localized near the plasma membrane. GP was distributed in the cytoplasm and transported to the plasma membrane independent of the other viral proteins. We also found that viral RNA synthesis occurred within the inclusions. Newly synthesized negative-sense RNA was distributed inside the inclusions, whereas positive-sense RNA was distributed both inside and outside. These findings provide useful insights into Ebola virus replication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ebola virus (EBOV), a member of the family Filoviridae, is an enveloped, single-stranded, negative-sense RNA virus that causes severe hemorrhagic fever with a high mortality rate in humans and nonhuman primates1. Currently there are no approved vaccines or treatments for Ebola virus infection.

The EBOV genome, which is approximately 19 kb in length, encodes seven structural proteins: NP, VP35, VP40, GP, VP30, VP24 and L1. The nucleoprotein (NP) is associated with the viral genome and assembles into a helical nucleocapside (NC) along with the polymerase cofactor (VP35), the transcription activator (VP30) and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L)2,3,4. The viral proteins that comprise the NC catalyze the replication and transcription of the viral genome4. A minor viral matrix protein, VP24 is also required for NC assembly. If NP is expressed alone in cells, it assembles together with cellular RNA to form a loose coil-like structure. When NP is co-expressed with VP24 and VP35, NC-like structures are formed in the cytoplasm that are morphologically indistinguishable from those seen in infected cells5,6,7,8,9. Our group and others previously showed that VP24 and the viral matrix protein VP40 reduce the transcription and replication efficiencies of the EBOV genome, suggesting that VP24 and VP40 are important for the conversion from a transcription and replication-competent NC to one that is ready for viral assembly10,11. VP40 plays a role in the formation and release of the enveloped, filamentous virus-like particles (VLPs) even when expressed alone12,13,14,15,16. NC-like structures are incorporated into VLPs when VP40 is co-expressed with NP, VP35 and VP24, suggesting that a direct interaction between VP40 and NP17 is important for the recruitment of NC-like structures to the budding site, the plasma membrane9,14. The interaction between VP40 and NP is also required for the formation of condensed NC-like structures6. GP is a surface glycoprotein that forms spikes on virions and plays a crucial role in virus entry into cells by mediating receptor binding and fusion18,19,20.

The assembly of viruses is a highly organized, complex process. The virus must orchestrate various processes including replication of the viral genome, expression of viral proteins and transport of individual viral components to the sites of virion formation. However, most studies of EBOV assembly have used exogenously expressed EBOV proteins rather than EBOV-infected cells2,15,16,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. The distribution of NP, VP35 and VP40 and the co-localization of NP with VP30 have been analyzed in EBOV-infected cells26,29. Also, the distribution of the viral proteins NP, VP35 and VP30, which are found in inclusion bodies and the co-localization of NP with VP35, VP30, or VP24 and VP40 with GP have been investigated in Marburg virus-infected cells2,21,24 However, the studies using filovirus-infected cells were done mainly at limited time points after infection. Moreover, the distribution dynamics of EBOV viral RNA transcription and replication are not yet fully understood.

We previously generated a replication-deficient, biologically contained EBOV, EbolaΔVP30, which lacks the essential VP30 gene and grows only in cells stably expressing VP3030. By using this system, here, we analyzed the spatio-temporal distribution dynamics of six of the seven EBOV-encoded proteins and virus-derived RNA in EbolaΔVP30-infected cells throughout the viral replication cycle.

Results

NP, VP35, VP30 and VP24 co-localize in cytoplasmic aggregates

We analyzed the distribution of six of the seven EBOV-encoded proteins (NP, VP35, VP40, GP, VP30 and VP24) by immunofluorescence staining of Vero-VP30 cells that had been synchronously infected with EbolaΔVP30; we were unable to analyze the distribution of the L protein in this assay due to the lack of a suitable anti-L antibody (Fig. 1). The co-localization of various combinations of the viral proteins was also examined by means of immunofluorescence double-staining (Fig. 2). We confirmed synchronous infection by demonstrating a similar staining pattern for NP in multiple-infected cells in the same field (Fig. S1). The distribution of NP was observed as small punctate dots in the cytoplasm by 6 hours post-infection (h.p.i.) (Fig. 1A). The dots became large aggregates near the nucleus from 12 to 24 h.p.i. These aggregates were likely viral inclusion bodies. The aggregated inclusions became smaller at approximately 36 h.p.i. Approximately 100–200 aggregates with an average diameter of 10 nm were detected in the infected cells. The small aggregates subsequently distributed near to the plasma membrane from 36 to 48 h.p.i (Fig. S2A). The kinetics of VP35 protein expression and its distribution pattern were almost identical to those of NP, suggesting that both NP and VP35 were present in the aggregates (Fig. 1B). Because EbolaΔVP30 lacks the VP30 gene, exogenously expressed VP30 is supplied for viral transcription30. VP30 was distributed in the cytoplasm as punctate dots in uninfected cells (Fig. 1E, bottom), whereas in EbolaΔVP30-infected cells, VP30 was incorporated into the inclusions, co-localizing with NP throughout the infection (Fig. 2D). VP24 protein was detected in the cytoplasmic inclusions at 18 h.p.i. and onward (Fig. 1F), where most of it co-localized with NP (Fig. 2E). However, at the early time points in the viral replication cycle, VP24 did not co-localized with NP.

Spatio-temporal distribution dynamics of EBOV proteins in EbolaΔVP30-infected cells.

Vero-VP30 cells were infected with EbolaΔVP30 at an m.o.i. of 0.1. The cells were fixed with 4% PFA at the indicated times after infection. The distribution of EBOV NP (A), VP35 (B), VP40 (C), GP (D), VP30 (E) and VP24 (F) was analyzed by use of immunofluorescence staining. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Yellow arrow (C, top) shows nuclear localization of VP40. Scale bars: 20 μm. White arrows indicate distribution patterns as described in the text.

Co-localization analysis of various combinations of EBOV proteins in EbolaΔVP30-infected cells.

Vero-VP30 cells were infected with EbolaΔVP30 at an m.o.i. of 0.1. The cells were harvested at the indicated times after infection. The co-localization of EBOV proteins was analyzed by use of double immunofluorescence staining in the following combinations: VP40 (red) and NP (green) (A), VP40 (red) and VP35 (green) (B), GP (red) and VP40 (green) (C), NP (red) and VP30 (green) (D), NP (red) and VP24 (green) (E). The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bars: 20 μm. The percentage of co-localization (proportion of co-localized protein to individual proteins) is shown in the individual panels.

VP40 is distributed in multiple subcellular compartments

VP40 was initially observed in the nucleoplasm by 6 h.p.i. (see yellow arrow in Fig. 1C, top). The punctate VP40 signals detected at 6 h.p.i. most likely came from viral particles that remained attached (see white arrows in Fig. 1C, top), because similar signals were also observed in cells immediately after adsorption (see white arrows in Fig. 1C, bottom). We did not detect signals for NP, VP35, or GP immediately after adsorption (Fig. 1A, B and D, bottom) probably because of the low number of these molecules in a single virion, compared with VP40 being the most abundant viral protein (Fig. S4). VP40 was subsequently distributed in the inclusions, along with NP and VP35 and in the nucleoplasm at 12 h.p.i. (Fig. 2A and B). VP40 was also distributed diffusely in the cytoplasm from 18 to 24 h.p.i. (Fig. 1C). A small fraction of VP40 was detected with a distinct signal at the plasma membrane at 18 h.p.i. (see white arrows in Fig. 1C, third panel from the top and Fig. S2B). The VP40 signal at the plasma membrane became more intense and appeared to represent a fibrous structure after 36 h.p.i. VP40 did not clearly co-localize with NP or VP35 in the smaller inclusions found at 36 h.p.i., but was present at the plasma membrane at 48 h.p.i. (Fig. 2A, B and Fig. S2C).

GP is distributed in the cytoplasm separately from the other viral proteins until it traffics to the plasma membrane

The GP signal was detected in the cytoplasm at 6 h.p.i. and in the perinuclear region from 12 to 36 h.p.i. (see white arrows in Fig. 1D). GP was distributed in a speckled pattern in the perinuclear region; it was subsequently distributed throughout the cytoplasm, away from the inclusions, or near the cytoplasmic VP40 (Fig. 2C). Unlike VP40, GP was not detected at the plasma membrane until a late stage of virus assembly (Fig. 1D and Fig. S2D). GP was extensively co-localized with VP40 at the plasma membrane at 48 h.p.i. (Fig. 2C).

Viral RNA is synthesized in the cytoplasm of EbolaΔVP30-infected cells

The replication and transcription of EBOV RNA is thought to take place in the cytoplasm of infected cells independently of cellular RNA synthesis in the nucleus31. We tested this concept by in situ labeling of replicated and transcribed viral RNA by using BrUTP. We transfected BrUTP into EbolaΔVP30-infected cells at 24 h.p.i. and incubated the cells for 2 h for chasing. The distribution of BrUTP-labeled RNA and VP40 were analyzed by means of immunofluorescence double-staining. BrUTP-labeled RNA was detected in the inclusions (Fig. 3A) and, after chasing for 12 h, it was found co-localized with VP40 at the plasma membrane (Fig. 3B).

Intracellular localization of EBOV RNA.

Vero-VP30 cells were infected with EbolaΔVP30 at an m.o.i. of 0.1. Vero-VP30 cells were pretreated for 30 min with actinomycin D at 24 h.p.i., transfected with 10 mM BrUTP and incubated for 2 h (A) or 12 h (B) in the presence of actinomycin D. The co-localization of BrUTP-labeled viral RNA (green) and VP40 (red) was analyzed by using immunofluorescence staining. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bars: 20 μm. The percentage of co-localization is shown in the individual panels.

The distributions of newly synthesized viral RNA in EbolaΔVP30-infected cells

The viral RNA genome released from EBOV virions is transcribed into seven mono-cistronic mRNAs to produce viral proteins32,33. Replication of the viral RNA genome results in the synthesis of a replicative intermediate, the positive-sense anti-genome, which is a complete copy of the negative-sense viral genome. This anti-genomic RNA in turn serves as a template for the generation of progeny viral genomes. We analyzed the distribution of newly synthesized positive- and negative-sense viral RNA by using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). We generated fluorescently labeled-specific sense and antisense probes for NP RNA, which allowed us to distinguish between negative- and positive-sense EBOV RNA. We then analyzed the co-localization of the viral RNA and NP by using a combination of FISH and immunofluorescence staining. Negative-sense RNA, which likely represented the newly synthesized viral genome, was co-localized with the inclusions at 6 h.p.i. (Fig. 4). The negative-sense RNA signals co-localized with the NP protein in the inclusions at 12 h.p.i. extensively and to a lesser extent at the plasma membrane at 48 h.p.i (Fig. S3). The antisense probe used in this study could not distinguish between viral mRNA and anti-genomic RNA. The positive-sense RNA signal was initially detected in the inclusions from 6 to 12 h.p.i., in the cytoplasm diffusely at 18 h.p.i and was undetectable at 48 h.p.i (Fig. 5).

Spatio-temporal distribution dynamics of negative-sense EBOV RNA in EbolaΔVP30-infected cells.

Vero-VP30 cells were infected with EbolaΔVP30 at an m.o.i. of 0.1. The cells were fixed with 4% PFA at the indicated times after infection. The co-localization of negative-sense viral RNA (green) and NP protein (red) was detected by using a combination of FISH and immunofluorescence staining. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bars: 20 μm. The percentage of co-localization is shown in the individual panels.

Spatio-temporal distribution dynamics of positive-sense EBOV RNA in EbolaΔVP30-infected cells.

Vero-VP30 cells were infected with EbolaΔVP30 at an m.o.i. of 0.1. The cells were fixed with 4% PFA at the indicated times after infection. The co-localization of positive-sense viral RNA (green) and NP protein (red) was detected by using a combination of FISH and immunofluorescence staining. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bars: 20 μm. The percentage of co-localization is shown in the individual panels.

Discussion

Here, we characterized the spatio-temporal distribution dynamics of six viral proteins (NP, VP35, VP40, GP, VP30 and VP24) and newly synthesized viral RNA in EbolaΔVP30-infected cells. We observed that VP40 was distributed to various sub-cellular compartments. VP40 was initially detected in the nucleoplasm at 6 h.p.i. (Fig. 1C), which is consistent with a previous report29. VP40 does not possess a putative nuclear localization signal, suggesting that as yet unknown cellular factors may associate with VP40 and participate in its transport to the nucleus. Further investigation is required to understand the role of VP40 in the nucleoplasm.

We and others previously demonstrated that NP expression alone results in the formation of intracellular aggregates17,25,26. Upon co-expression with VP40, NP co-localizes with VP40 and is transported to the plasma membrane without the formation of cytoplasmic aggregations17. In our present study, VP40 was detected in inclusion bodies from 18 to 36 h.p.i., possibly forming NC-VP40 complexes (Fig. 2A and B). VP40 was also found at the plasma membrane from 12–18 h.p.i. (Fig. 1C and Fig. 2A-C), suggesting that some of the VP40 that is diffusely distributed in the cytoplasm migrates to the plasma membrane.

The aggregated inclusions became smaller at 36 h.p.i. and later appeared near the plasma membrane (Fig. 1A and B). No appreciable co-localization of VP40 with the small aggregates was observed (Fig. 2A and B). Intracellular transport of VP40 is mediated by the COPII transport system, which is dependent on microtubules9,28. However, the role of the COPII transport system in VP40-mediated NC recruitment remains unclear. Also, it is not clear whether the NC associates with vesicles during its intracellular transport. Therefore, it is not clear whether COPII-mediated VP40 transport to the plasma membrane involves only the free VP40 observed at 12–18 h.p.i. or also includes VP40-NC complexes. Further investigations are needed to understand the roles of viral and host factors in the dynamic changes in the size of these inclusions and in the transport of the NC to the plasma membrane.

The perinuclear localization of GP (Fig. 1D and 2C) suggests that GP is present in the ER and Golgi apparatus, as has been shown previously22. Further analyses with ER or Golgi markers would support this contention. In addition to the transmembrane GP, the Ebola virus glycoprotein gene encodes the soluble glycoprotein sGP34. Because the antibody to GP used in this study also reacts with sGP, we could not distinguish between the distribution of full-length GP and that of sGP in this study.

Not all de novo synthesized RNA was co-localized with VP40 (Fig. 3). Viral proteins that co-localize with de novo synthesized RNA should be identified in future experiments.

We found that negative-sense viral RNA co-localized with NP throughout the viral assembly process (Fig. 4), suggesting that the de novo synthesized viral genome is immediately incorporated into the NC. However, the negative-sense viral RNA did not co-localize with NP efficiently at 36 and 48 h.p.i. compared with earlier time points. The reason for this reduced co-localization of negative-sense viral RNA and NP remains unknown.

We also observed that the positive-sense viral RNA signal decreased at 48 h.p.i. (Fig. 5, bottom), which is consistent with a previous report in which the synthesis of viral mRNA was shown to decrease after 18 h.p.i. and terminate at 48 h.p.i33. Because the antisense probe used in this study could not distinguish between viral mRNA and anti-genomic RNA, probes that specifically react with each of these RNA species are needed for future studies designed to better understand the spatio-temporal distribution dynamics of these RNA species.

Our previous report indicated that the replication kinetics of EbolaΔVP30 are approximately 10-times faster than those of the wild-type virus at early time points after infection in cells over-expressing VP3030. While the kinetics of VP30 expression is tightly regulated in wild-type EBOV-infected cells, VP30 is constantly over-expressed in the EbolaΔVP30 system. Because viral replication and transcription are dependent on the expression level of VP304,23,25,26,35,36,37,38,39, the kinetics of viral genome transcription, replication and gene expression may differ between EbolaΔVP30 and wild-type EBOV. Therefore, some of the findings described in this study should be repeated with authentic EBOV.

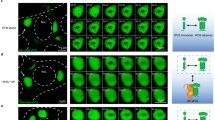

In summary, our findings, together with previous data1,5,6,9 suggest the following model for EBOV virion formation (Fig. 6): Viral mRNA is transcribed from genomic negative-sense RNA, is released into the cytoplasm and viral proteins are translated. NP, together with VP35, VP40, VP30 and VP24 forms small inclusions (A), which become larger near the nucleus (B). At the edge of the inclusion bodies, the NC is formed9. VP40 associates with the NC, contributing to its transport to the plasma membrane9 (C1). Alternatively, NC initially associates with a few VP40 molecules and is then transported to the plasma membrane, where it is enveloped with membrane-associated VP40 (C2). Synthesized GP is transported to the plasma membrane (D) and assembled into the viral particles (E). This proposed model, especially early in the infection, may apply to only our biologically contained Ebola virus system in which the results may be affected by the overexpression of VP30. The relevance of this model in authentic Ebola virus needs to be further investigated to better understand EBOV replication.

A model of EBOV assembly.

Viral mRNA is transcribed from genomic negative-sense RNA, is released into the cytoplasm, where viral proteins are translated. NP, together with VP35, VP40, VP30 and VP24 forms small inclusions (A), which become larger near the nucleus (B). At the edge of the inclusion bodies, the NC is formed. VP40 associates with the NC, contributing to its transport to the plasma membrane (C1). Alternatively, NC initially associates with a few VP40 molecules and then moves to plasma membrane, where it is enveloped with membrane-associated VP40 (C2). Synthesized GP is independently transported to the plasma membrane (D). The viral components then assemble and the progeny virions bud (E).

Methods

Cell culture

African green monkey kidney epithelial Vero cells stably expressing EBOV VP30 protein (Vero-VP30)30 were grown in minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), L-glutamine, vitamins, nonessential amino acids, antibiotics and 5 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). The cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Immunofluorescence staining

For synchronous infection Vero-VP30 cells grown on cover slips were incubated with EbolaΔVP30, in which the viral VP30 ORF was replaced with the neomycin-resistance gene30 at an m.o.i. of 0.1 in MEM supplemented with 2% FBS and 4% BSA on ice for 1 h for adsorption, washed to remove unbound viruses and incubated for various times at 37°C in the same medium. Vero-VP30 cells were harvested, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, permeabilized with PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature and blocked in PBS containing 4% BSA and 0.05% Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature. For VP24 staining, the cells were fixed with cold methanol at −20°C for 4 min, washed in PBS and blocked in PBS containing 4% BSA. The cells were then incubated with a rabbit anti-NP polyclonal antibody (cl. 5070 9-20; 1:3000 dilution), a mouse anti-NP monoclonal antibody (cl. 7-71.5; 1:2000 dilution), a mouse anti-VP35 monoclonal antibody (cl. 5; 1:1000 dilution), a rabbit anti-VP40 polyclonal antibody (cl. R266; 1:3000 dilution), a mouse anti-GP monoclonal antibody (cl. 226/8.1; 1:2000 dilution), a rabbit anti-VP30 polyclonal antibody (cl. 3; 1:1000 dilution), or a mouse anti-VP24 monoclonal antibody (cl. 21-7.7; 1:1000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were then washed twice in PBS and incubated with AlexaFluor™ 488 or 594-labeled secondary antibodies (1:5000 dilution) (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were subsequently washed twice in PBS and nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The images (0.8 μm thickness z-slice) were acquired by use of a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM510 META, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a digital CCD camera (Axiocam HRm; Zeiss), 405 nm diodelaser (for DAPI excitation), a 488 nm argon laser (for AlexaFluor™ 594 excitation) and a 543 nm HeNe laser (for AlexaFluor™ 594 excitation). Images were collected with a 40x oil objective lens (C-Apochromat, NA = 1.2, Carl Zeiss) and acquired by using LSM510 software (Carl Zeiss). Twenty fields containing approximately 20 to 30 virus-infected cells were randomly collected at each time point and representative images are shown. We scanned eight times to obtain an average and reduce the background. For presentation in this manuscript, all images were digitally processed with Adobe Photoshop. Co-localization percentages (proportion of co-localized protein to total protein) of single slices of individual images were analyzed by measuring the co-localization coefficient with Zeiss LSM 510 software.

BrUTP-labeling of newly synthesized viral RNA

Vero-VP30 cells grown on cover slips were infected with EbolaΔVP30 at an m.o.i. of 0.1. At 24 h.p.i., they were pretreated for 30 min with 1 μg/ml actinomycin D (Sigma-Aldrich) to inhibit RNA polymerase II-dependent cellular transcription. The cells were then transfected with 10 mM 5-Bromouridine 5′-triphosphate (BrUTP; Sigma-Aldrich) using the transfection reagent FuGENE 6 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and subsequently incubated for 2 or 12 h in the presence of actinomycin D. The cells were fixed, permeabilized and blocked as described in the procedure for immunofluorescence staining. The cells were incubated with an anti-BrdUTP monoclonal antibody (1:200 dilution) (Roche) and a rabbit anti-NP polyclonal antibody (cl. 5070 9-20; 1:3000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature, respectively. The cells were washed twice in PBS and incubated with AlexaFluor™-labeled secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were washed twice in PBS and the nuclei were counterstained with DAPI.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

The template for the sense and anti-sense hybridization probes for the detection of negative- and positive-sense viral RNA, respectively, was generated by inserting the NP cDNA between the T7 and SP6 promoters of the pcDNA3 plasmid (Life Technologies). The sense or anti-sense probe was synthesized under the control of the T7 or SP6 RNA promoter, respectively and labeled with AlexaFluor™-488 by using the FISHTag™ RNA Green Kit (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer's protocol. Vero-VP30 cells grown on cover slips were infected with EbolaΔVP30 at an m.o.i. of 0.1. The cells were harvested at various time points after infection, washed twice in cold PBS containing 5 mM MgCl2 (PBS-M), permeabilized in PBS containing 0.25% Triton X-100 for 1 min at room temperature and fixed with 4% PFA for 10 min at room temperature. After being washed twice with ice-cold PBS-M, the cells were equilibrated in pre/post hybridization buffer [50% formamide, 2 x SSC (1 x SSC: 0.15 M NaCl, 0.015 M sodium citrate)] for 10 min at room temperature. Each probe (10 ng) was mixed with 1 μg of salmon sperm DNA (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) and 1 μg of yeast tRNA (Sigma-Aldrich), resuspended in CEP hybridization buffer (Abbotto Molecular, Abbott Park, IL), denatured for 2 min at 80°C and placed on ice. The cells were incubated with a hybridization mix containing probe overnight at 55°C. The cells were then washed twice in pre/post hybridization buffer for 20 min at 55°C, in 2 x SSC for 10 min at room temperature and in PBS-M for 10 min at room temperature. For double-staining with the NP protein, following the wash, the cells were subsequently blocked and incubated with a rabbit anti-NP polyclonal antibody (cl. 5070 9-20; 1:3000 dilution) and AlexaFluor™-labeled secondary antibodies as described in the procedure for immunofluorescence staining.

References

Sanchez, A., Geisbert, T. & Feldmann, H. Filoviridae: Marburg and Ebola viruses, p 1409–1448. In Knipe, D. M., Howley, P. M. (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed. Lippincott/Williams & Wilkins Co, Philadelphia, PA. (2007).

Becker, S., Rinne, C., Hofsass, U., Klenk, H. D. & Muhlberger, E. Interactions of Marburg virus nucleocapsid proteins. Virology 249 (2), 406–417 (1998).

Muhlberger, E., Lotfering, B., Klenk, H. D. & Becker, S. Three of the four nucleocapsid proteins of Marburg virus, NP, VP35 and L, are sufficient to mediate replication and transcription of Marburg virus-specific monocistronic minigenomes. J Virol 72 (11), 8756–8764 (1998).

Muhlberger, E., Weik, M., Volchkov, V. E., Klenk, H. D. & Becker, S. Comparison of the transcription and replication strategies of marburg virus and Ebola virus by using artificial replication systems. J Virol 73 (3), 2333–2342 (1999).

Beniac, D. R. et al. The organisation of Ebola virus reveals a capacity for extensive, modular polyploidy. PLoS One 7 (1), e29608 (2012).

Bharat, T. A. et al. Structural dissection of Ebola virus and its assembly determinants using cryo-electron tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109 (11), 4275–4280 (2012).

Huang, Y., Xu, L., Sun, Y. & Nabel, G. J. The assembly of Ebola virus nucleocapsid requires virion-associated proteins 35 and 24 and posttranslational modification of nucleoprotein. Mol Cell 10 (2), 307–316 (2002).

Mateo, M. et al. Knockdown of Ebola virus VP24 impairs viral nucleocapsid assembly and prevents virus replication. J Infect Dis 204 Suppl 3, S892–896 (2011).

Noda, T. et al. Assembly and budding of Ebolavirus. PLoS Pathog 2 (9), e99 (2006).

Hoenen, T., Jung, S., Herwig, A., Groseth, A. & Becker, S. Both matrix proteins of Ebola virus contribute to the regulation of viral genome replication and transcription. Virology 403 (1), 56–66 (2010).

Watanabe, S., Noda, T., Halfmann, P., Jasenosky, L. & Kawaoka, Y. Ebola virus (EBOV) VP24 inhibits transcription and replication of the EBOV genome. J Infect Dis 196 Suppl 2, S284–290 (2007).

Hoenen, T. et al. Oligomerization of Ebola virus VP40 is essential for particle morphogenesis and regulation of viral transcription. J Virol 84 (14), 7053–7063 (2010).

Jasenosky, L. D., Neumann, G., Lukashevich, I. & Kawaoka, Y. Ebola virus VP40-induced particle formation and association with the lipid bilayer. J Virol 75 (11), 5205–5214 (2001).

Noda, T. et al. Ebola virus VP40 drives the formation of virus-like filamentous particles along with GP. J Virol 76 (10), 4855–4865 (2002).

Timmins, J., Scianimanico, S., Schoehn, G. & Weissenhorn, W. Vesicular release of ebola virus matrix protein VP40. Virology 283 (1), 1–6 (2001).

Yamayoshi, S. & Kawaoka, Y. Mapping of a region of Ebola virus VP40 that is important in the production of virus-like particles. J Infect Dis 196 Suppl 2, S291–295 (2007).

Noda, T., Watanabe, S., Sagara, H. & Kawaoka, Y. Mapping of the VP40-binding regions of the nucleoprotein of Ebola virus. J Virol 81 (7), 3554–3562 (2007).

Feldmann, H., Volchkov, V. E., Volchkova, V. A. & Klenk, H. D. The glycoproteins of Marburg and Ebola virus and their potential roles in pathogenesis. Arch Virol Suppl 15, 159–169 (1999).

Lee, J. E. et al. Structure of the Ebola virus glycoprotein bound to an antibody from a human survivor. Nature 454 (7201), 177–182 (2008).

Nanbo, A. et al. Ebolavirus is internalized into host cells via macropinocytosis in a viral glycoprotein-dependent manner. PLoS Pathog 6 (9), e1001121 (2010).

Bamberg, S., Kolesnikova, L., Moller, P., Klenk, H. D. & Becker, S. VP24 of Marburg virus influences formation of infectious particles. J Virol 79 (21), 13421–13433 (2005).

Bhattacharyya, S. & Hope, T. J. Full-length Ebola glycoprotein accumulates in the endoplasmic reticulum. Virol J 8, 11 (2011).

Hartlieb, B., Modrof, J., Muhlberger, E., Klenk, H. D. & Becker, S. Oligomerization of Ebola virus VP30 is essential for viral transcription and can be inhibited by a synthetic peptide. J Biol Chem 278 (43), 41830–41836 (2003).

Kolesnikova, L., Berghofer, B., Bamberg, S. & Becker, S. Multivesicular bodies as a platform for formation of the Marburg virus envelope. J Virol 78 (22), 12277–12287 (2004).

Modrof, J. et al. Phosphorylation of Marburg virus VP30 at serines 40 and 42 is critical for its interaction with NP inclusions. Virology 287 (1), 171–182 (2001).

Modrof, J., Muhlberger, E., Klenk, H. D. & Becker, S. Phosphorylation of VP30 impairs ebola virus transcription. J Biol Chem 277 (36), 33099–33104 (2002).

Noda, T., Halfmann, P., Sagara, H. & Kawaoka, Y. Regions in Ebola virus VP24 that are important for nucleocapsid formation. J Infect Dis 196 Suppl 2, S247–250 (2007).

Yamayoshi, S. et al. Ebola virus matrix protein VP40 uses the COPII transport system for its intracellular transport. Cell Host Microbe 3 (3), 168–177 (2008).

Bjorndal, A. S., Szekely, L. & Elgh, F. Ebola virus infection inversely correlates with the overall expression levels of promyelocytic leukaemia (PML) protein in cultured cells. BMC Microbiol 3, 6 (2003).

Halfmann, P. et al. Generation of biologically contained Ebola viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 (4), 1129–1133 (2008).

Whelan, S. P., Barr, J. N. & Wertz, G. W. Transcription and replication of nonsegmented negative-strand RNA viruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 283, 61–119 (2004).

Muhlberger, E. et al. Termini of all mRNA species of Marburg virus: sequence and secondary structure. Virology 223 (2), 376–380 (1996).

Sanchez, A. & Kiley, M. P. Identification and analysis of Ebola virus messenger RNA. Virology 157 (2), 414–420 (1987).

Sanchez, A., Trappier, S. G., Mahy, B. W., Peters, C. J. & Nichol, S. T. The virion glycoproteins of Ebola viruses are encoded in two reading frames and are expressed through transcriptional editing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93 (8), 3602–3607 (1996).

Hartlieb, B., Muziol, T., Weissenhorn, W. & Becker, S. Crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of Ebola virus VP30 reveals a role in transcription and nucleocapsid association. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 (2), 624–629 (2007).

John, S. P. et al. Ebola virus VP30 is an RNA binding protein. J Virol 81 (17), 8967–8976 (2007).

Martinez, M. J. et al. Role of Ebola virus VP30 in transcription reinitiation. J Virol 82 (24), 12569–12573 (2008).

Martinez, M. J. et al. Role of VP30 phosphorylation in the Ebola virus replication cycle. J Infect Dis 204 Suppl 3, S934–940 (2011).

Weik, M., Modrof, J., Klenk, H. D., Becker, S. & Muhlberger, E. Ebola virus VP30-mediated transcription is regulated by RNA secondary structure formation. J Virol 76 (17), 8532–8539 (2002).

Acknowledgements

We thank Martha McGregor for excellent technical assistance and Susan Watson for editing the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from NIH R01 AI055519 and the Region V “Great Lakes” Regional Center of Excellence (National Institutes of Health Grant 1-U54-AI-057153) and by ERATO and the Global Center of Excellence (G-COE) for Education and Research on Signal Transduction (Japan Science and Technology Agency).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N. designed and performed the experiments, S.W. provided conceptual suggestions for the experimental design, A.N. and Y.K. wrote the manuscript and P.H. established the experimental system. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Nanbo, A., Watanabe, S., Halfmann, P. et al. The spatio-temporal distribution dynamics of Ebola virus proteins and RNA in infected cells. Sci Rep 3, 1206 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01206

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01206

This article is cited by

-

Spatial and functional arrangement of Ebola virus polymerase inside phase-separated viral factories

Nature Communications (2023)

-

The two-stage interaction of Ebola virus VP40 with nucleoprotein results in a switch from viral RNA synthesis to virion assembly/budding

Protein & Cell (2022)

-

Ebola virus VP35 hijacks the PKA-CREB1 pathway for replication and pathogenesis by AKIP1 association

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Identification of interferon-stimulated genes that attenuate Ebola virus infection

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Global phosphoproteomic analysis of Ebola virions reveals a novel role for VP35 phosphorylation-dependent regulation of genome transcription

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.