Abstract

Sharks and rays' abundance can decline considerably with fishing. Community changes, however, are more complex because of species interactions and variable vulnerability and exposure to fishing. We evaluated long-term changes in the elasmobranch community of the Adriatic Sea, a heavily exploited Mediterranean basin where top-predators have been strongly depleted historically and fishing developed unevenly between the western and eastern side. Combining and standardizing catch data from five trawl surveys from 1948–2005, we estimated abundance trends and explained community changes using life histories, fish-market and effort data and historical information. We identified a highly depleted elasmobranch community. Since 1948, catch rates have declined by >94% and 11 species ceased to be detected. The exploitation history and spatial gradients in fishing pressure explained most patterns in abundance and diversity, including the absence of strong compensatory increases. Ecological corridors and large-scale protected areas emerged as potential management options for elasmobranch conservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Analyses of exploited fish communities in coastal, demersal and pelagic ecosystems have shown that elasmobranch (sharks and rays) diversity and abundance can decline considerably after only short periods of fishing1,2,3. For example, in the Northwest Atlantic, catch rates of 18 large pelagic and coastal shark declined by 49–89% in less than 15 years2. In South Africa, large coastal sharks were reduced by 27% - >99% after 20 years of shark netting programs1 and in Southeast Australia, 20 years of trawling reduced demersal elasmobranch catch rates by >80%3. Industrial bottom trawl fisheries in particular can have strong effects on demersal communities by unselectively catching a wide range of species while destroying complex seafloor habitats4,5.

Aside from declines in population abundance, shifts in community composition can occur because fishes have different intrinsic vulnerabilities to exploitation, are unequally exposed to fishing and respond to changes in predators and competitors. Any species is characterized by an intrinsic rebound potential (r), a population parameter that combines a set of biological traits (maturity, fecundity and growth) determining the species productivity and capacity to sustain exploitation6. As a group, elasmobranchs generally have very low r values due to their late sexual maturity, low fecundity and slow growth rate, hence they are unable to sustain even moderate levels of exploitation7,8. Yet even among elasmobranchs, r is variable enough9,7 to sometimes explain observed differences in the species' response to fishing10,11. In other cases, variable exposure to fishing12,13,3 and changes in the abundance of predators and competitors12,14,15,16,17 have been more important predictors of community change.

Predation is an important factor explaining meso-predator population dynamics and community changes in terrestrial18 and aquatic ecosystems19. Among elasmobranchs, large sharks are the main predators of smaller sharks and rays20. While many large sharks have declined over the last decades, meso-predatory elasmobranchs have increased in exploited communities of the Atlantic21,17,15,12, Pacific22,3 and Indian Ocean23,24. However, the magnitude and trajectory of population increases are not always predictable because prey benefit from both reduced natural mortality and a reduced risk of predation25,18. The latter is a more pervasive but not easily quantifiable behaviorally-mediated effect that influences prey distribution, habitat and food choices and overall fitness25. Moreover, while sharing common predators, sympatric species compete for limiting resources, which influence their abundance. When fishing or other human impacts selectively deplete or removes species26, releases from competition are often predicted and were suggested to explain unexpected increases in elasmobranchs in several areas, of the world21,16,17,27. Yet in some of these cases, alternative explanations, such as shifts in spatial distribution, also played a role28.

Explaining community changes in large marine ecosystems by identifying the occurrence and relative contribution of direct and indirect effects of fishing, or other human impacts, is challenging because it requires performing controlled experiments impractical at large scales. In these cases, adopting an observational approach across gradients of natural or human-induced perturbations is an efficient alternative19. We used such an approach to study the long-term changes in the elasmobranch community of the Adriatic Sea, whose long history of human-induced changes, as well as the spatial and temporal contrasts of perturbations, offered an ideal case study. The Adriatic Sea is a semi-enclosed Mediterranean basin that has been exploited for thousands of years and where large marine predators (sharks, pinnipeds and cetaceans) have declined dramatically over the past two centuries29. The Adriatic's broad continental shelf and accessible fishing grounds allowed the development of large fisheries for shellfish and groundfish30. Yet fisheries developed unevenly between the western and eastern sides of the basin. While Italian waters were exposed to extremely high exploitation pressure from high-capacity fishing fleets, former Yugoslavian sectors sustained a much lighter fishing exploitation until recently (see Supplementary Methods for a brief fishing and ecosystem depletion history).

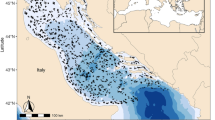

To examine spatial and temporal changes in the elasmobranch community, we used data from five different scientific trawl surveys carried out in the Adriatic since 1948 (Fig. 1, Table 1). First, we extracted species-specific trends of catch rates to estimate short-term community changes within surveys. Then we estimated long-term community changes comparing catches across surveys. Finally, we used life-history characteristics, environmental factors (e.g. sediment composition, temperature), fishing effort data and historical fishing information to explain the observed trajectories of population and community changes. It was our aim to identify the main drivers of change, whether the decline of large predatory sharks triggered meso-predator releases and if there was a change of the elasmobranch community composition suggesting competitive interactions.

Positions of tows performed during the surveys analyzed in the Adriatic Sea.

Survey details are in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1.

Results

In total, 2575 tows carried out over six decades across the Adriatic Sea detected 33 small, demersal, meso-predatory elasmobranch species (average trophic level: 3.9, SD: 0.1231), including 12 sharks, 20 rays and one chimaera (included for their evolutionary and ecological similarity, Table 2). Of these, 11 species ceased to be detected during the period of observation (no more occurrences after the year 2000, Table 2), while 6, mostly deep-water species and small skates, were only recently detected by the MEDITS surveys which expanded to greater sampling depths (Table 2).

Across all five surveys, species-specific frequency distributions were very skewed (Fig. 2), with few dominant species and many occurring only sporadically. The Hvar survey detected the highest diversity (23 species, Shannon Index [SI]: 3.39, Fig. 2a), dominated by small-spotted cat sharks and thornback skates with unstandardized densities of 426.8 and 76.8 individuals/km2, respectively and frequencies of occurrence (FO) of 0.76 and 0.71. The other 21 species were caught in < 21% of the tows with densities below 11 ind./km2. Over time, moving to the most recent survey, richness and abundance decreased toward more flattened and truncated distributions. In MEDITS (SI: 1.96), the small-spotted catshark was still the most abundant species, but with a density of 62.1 ind./km2 and FO of 0.20 (Fig. 2), a 6.8- and 3.8-fold decline, respectively, compared to Hvar. Overall, 21 out of 27 species had FO < 0.021 and densities < 4 ind./km2. The high elasmobranch abundance and diversity characterizing the central Adriatic during the Hvar survey in 1948–49 disappeared (Fig. 3a and b). Yet, species richness and abundance were higher in the eastern coastal areas than elsewhere (Fig. 3a and b). Elasmobranch abundance in Croatia was almost one order of magnitude higher than in Italy (Supplementary Fig. S1), where sharks and rays were largely absent except for a relatively high-density zone in the upper Adriatic (above the 50 m isobath, Fig. 3a MEDITS) mainly composed of spurdogs (Supplementary Fig. S2), smooth-hounds and eagle rays.

Frequency of occurrence (FOi) and mean density of elasmobranchs caught in the analyzed surveys and Adriatic fishing effort.

FOi of Hvar (a), Zupanovic (b), Jukic (c), GRUND (d) and MEDITS (e) are indicated with grey bars (number of hauls with speciesi/total number of hauls performed). Red fillings are the species mean density (n/km2, unstandardized catches). (f) Projected fishing effort distribution in the Adriatic Sea. Color scale refers to the logarithm of the expected horse powers (HPs) deployed per day in a given 0.02 × 0.02 degree cell. Red dots are major Adriatic ports.

Standardized catches generally confirmed the above patterns. Although the fitted models had considerable selection uncertainty - in each survey, more than half of the species had a selected best model with <10% chance (Akaike weight <0.1) of being the most plausible among a 95% confidence set of models (see methods, Supplementary Tables S2–S6) – spatial covariates (depth, latitude and longitude) resulted as the best predictors of species abundance (Tables 3 and S2–S6). In the largest surveys available (Hvar and MEDITS), these predictors pointed to an increase in catch rates from the Italian to the Croatian coasts and for most species from deep to shallow waters (i.e. from offshore to inshore, Supplementary Fig. S3). Temporal covariates (year, time of the year) were less important than spatial variables, but many species had significant short-term temporal trends within surveys (Fig. 4).

Short-term trends.

Raindrop plot of βys′ profile likelihoods for elasmobranchs detected during the Jukic (1963–1972, a) and MEDITS surveys (1994–2005, b). Drop widths indicate the 95% CI of βy. Drop thickness at a particular βy value indicates the relative plausibility of that value. Green raindrops indicate sharks. Orange indicates rays. The rabbit fish is in grey.

Analyses of catches in the Jukic survey (1963–1971), located in the central eastern Adriatic, identified nine species with reliable short-term trends in abundance and all except the thornback skate showed an increase in standardized catches (three species were significant, Fig. 4a). In comparison, between 1994 and 2005 across the Adriatic (MEDITS surveys), 16 species had reliable estimates of population change. Of these, nine species, mainly sharks, showed declines (3 statistically significant, Fig. 4b), while increases were mostly shown by meso-pelagic rays and small skates; yet these trends were not significant except that for the eagle ray, which increased by 3.74 times (Confidence Interval, CI: 1.06, 13.45) in 11 years.

Over longer periods of time, changes in abundance were larger and more significant. Comparing Hvar and MEDITS surveys showed that elasmobranchs declined by 94.5% over 57 years (Fig. 5a and b). Sharks declined more than rays (−95.6% vs. −87.7%) with small-spotted catsharks (−96.2%, CI: −97.8%, −93.5%) driving most of the patterns. Rays shifted in species composition. In particular, the thornback skate, the most abundant ray in the 1940s, recorded the steepest decline (−97.2%, CI: −98.4%, −95%), whereas brown skates increased by 2.36 times (CI: 1.05, 5.3) becoming the most abundant skates (Fig. 2e). Significant long-term increases were also detected for eagle rays (111 times, CI: 17.05, 735), marbled torpedoes (75.9 times, CI: 5.07, 1135.64) and spurdogs (3.1 times, CI: 1.05, 9.27) (Fig. 5a and b).

Long-term changes.

(a) Long-term changes of standardized CPUEs of elasmobranch species and aggregated groups detected in the Hvar spatial domain (Figure 1) by Hvar and MEDITS surveys. Grey bars (with upper 95% confidence intervals) are standardized CPUEs recorded in the Hvar survey and red bars are those recorded in MEDITS. The expected CPUEs are calculated for a location correspondent to the average depth of all tows occurring in the comparison area, in mid July. The inset is a magnification of the bars inside the red polygon. (b–e) Centipede plots of catch rate changes (in % relative to initial level or factor of increase) for species (circles) and aggregated groups (triangles) estimated in the long-term comparisons of trawl surveys. The species considered in each panel occurred for three or more years in their respective long-term comparison. Green indicates sharks, orange rays and grey specifies all elasmobranchs aggregated.

In the coastal area off the eastern Adriatic (Zupanovic area, Fig. 1), between 1957 and 2005 elasmobranchs increased significantly by 2.12 times (CI: 1.59, 2.83). Rays increased faster than sharks (3.79 vs. 1.88 times) with brown skate and common eagle rays recording fold increases of 17.7 (CI: 9.9, 31.7) and 19.73 (CI: 7.08, 55.03) respectively. As for sharks, the patterns were largely driven by the almost 2-fold increase of small-spotted catsharks (1.92, CI: 1.1, 3.4). The smooth-hound recorded the largest increase (21.13, CI: 8.23, 54.25) and the thornback skate was the only elasmobranch showing a significant decline (−39.8%, CI: −63.14%, −1.77%) (Fig. 5c).

In the Jukic area, comparing catch rates in the period 1948–1971 (Hvar-Jukic comparison), elasmobranchs declined by 61% in 23 years. These were mainly sharks (−61%), while rays recorded a moderate and non-significant decline (−38%), although brown skates suggested some increase and the common eagle ray increased by 128 times (CI: 46, 358). The spurdog was the only shark increasing significantly (4.43-fold, CI: 1.43–13.72), while 4 of the other 5 species we could model recorded declines between −63% (small spotted cat-shark, CI: −83.6%, −16.6%) and −96.8% (the smooth-hound, CI:−98.7, −92%). In contrast, in the period 1963–2005 (Jukic-MEDITS comparison), sharks and rays as a group declined comparably and significantly by more than 90%. Spurdogs reversed their earlier increase with a decline of −87.6% (CI: −95.2%, −68%) and the increase of common eagle rays became non significant. This time, smooth-hounds recorded the only significant increase (356 times, CI: 6.8, 18534; Fig. 5e).

All these results were robust to mis-specification and uncertainty of trawl performance (in terms of swept area), to sampling and estimation error of sediment composition and to the surveys' sample sizes (see Supplementary Methods).

Our projected distribution of current fishing intensity (Fig. 2f) reflected the patterns in abundance and distribution detected in MEDITS (except for the upper Adriatic Sea, Fig. 3) and was consistent with the spatial parameter estimates of the standardized catches (Supplementary Fig. S3). The eastern Adriatic (mainly fished by Croatia) has a much lower level of fishing pressure than the western side (exploited by Italy). Italy records about twice the amount of otter trawlers (1541) than Croatia (855) with an average trawler having about 2.25 times the Horse Power (199 HP, sd = 149) of an average Croatian one (88.5 HP)32. We predicted a higher fishing intensity all along the northwestern Adriatic, especially between Fano and Pescara and around Chioggia (Fig. 2f). While in Croatia, heavily fished areas would be the southeastern part of Istria and above the Dalmatian channels between Sibenik and Split. Note that the distribution of fishing effort was coarser in Croatia because our source data was aggregated by major fishing districts and we assumed that the allocation of fishing boats per port was proportional to the port population density (Supplementary Materials). Dividing the number of boats fishing in these different Croatian sectors by the sectors' trawable surface (i.e. excluding 3 nautical miles from the shores) showed that most of the Croatian channel region would be free from trawling, which instead would take place mostly in the coastal areas (between 3 and 6 nautical miles) of Istria and the outer channel areas (Supplementary Fig. S4). If the number of otter trawlers longer than 18 meters is a good index of offshore fishing intensity (between 3 and 40 nautical miles), fishing exploitation is an order of magnitude higher in Italian than Croatian waters (0.005 vs. 0.0003 boats per square kilometer, Supplementary Fig. S4).

The intrinsic vulnerability of species did not explain the variability of the observed rates of change. We found no significant relationships between r and βys estimated from MEDITS (slope 0.996, p-value: 0.504, R2: 0.035) Jukic (slope = 3.499, p-value 0.152, R2: 0.27), historical comparisons in the Hvar area (slope = 14.020, p-value: 0.51, R2: 0.039), Jukic area between Hvar and Jukic (slope = 5.91, p-value: 0.75, R2: 0.013), Jukic area between Jukic and MEDITS (slope = 14.53, p-value = 0.45, R2: 0.072) and in the Zupanovic area (slope = 23.61, p-value: 0.18, R2: 0.21).

Discussion

Understanding long-term changes in exploited fish communities requires the consideration of several factors, including the intrinsic vulnerability of various species to exploitation, changes in biological interactions (e.g. predation and competition), different exposure to fishing (e.g. catchability, availability and commercial value) and susceptibility to other stressors such as habitat degradation and pollution. All of these factors can alter the species-specific response to exploitation, generating complex community changes over time and space1. Here, we attempted to understand long-term changes in the elasmobranch community in the Adriatic Sea and the underlying drivers.

By analyzing trawl surveys carried out in the area over the last six decades, we detected a structurally depleted elasmobranch community. A total of 2575 tows were not sufficient to detect at least 25 elasmobranch species that were recorded in the area before 1948 (Supplementary Table S7). These included 13 great sharks (>2 m in length), which may not have been caught due to their lower trawl catchability compared to demersal species, but also 8 bottom associated large meso-predatory elasmobranchs (e.g. angelsharks, guitarfishes, large rays, bramble and gulper sharks, Supplementary Table S7), some of which were the target of dedicated fisheries33,34. Most of the 33 species detected by the trawl surveys strongly declined over time and 11 disappeared, updating the list of possible extinctions in the Adriatic Sea14,1 to 22 species. Overall, sharks declined stronger than rays (−95.6% vs. −87.7%) and more shark than ray species recorded significant declines (4 vs. 2 species respectively, Hvar-MEDITS comparison Fig. 5b). Similar strong depletions of elasmobranch abundance and diversity were recorded in exploited fishing grounds of the North Sea27, southeastern Australia3, the Tyrrhenian Sea35 and the Gulf of Lions36. However, none of these studies covered trends across six decades with standardized fishery independent data.

The Mediterranean Sea in general and the Adriatic Sea in particular, have experienced a long history of human impacts, including exploitation, pollution and habitat degradation, resulting in severe population declines of marine species37,29. With our data starting in 1948, we only captured a final stage of this depletion history, with many large sharks already depleted or absent. However, we found a higher abundance and diversity of elasmobranchs in the eastern Adriatic (Fig. 3a and b) which reflected the less intense historical and recent fishing pressure in Croatian compared to Italian waters (Fig. 2f), especially in coastal Croatian waters were trawling has been restricted, discouraged or hardly practicable38 (also see Supplementary Fig. S4). This good correspondence between the spatial gradient of fishing pressure and the observed patterns of elasmobranch abundance and diversity suggests that fishing has been a strong driver of the observed changes. Other human impacts, such as pollution and habitat degradation, were likely also stronger on the more highly populated Italian coast and may have contributed to the observed declines.

Differences in the intrinsic vulnerabilities among species (reflected by their rebound potential r) were not sufficient to explain the observed species-specific rates of change. They were suggestive of a positive but not significant relationship between vulnerability and rate of decline. The surveys detected a limited and biased sample of species whose life histories did not represent the full spectrum characterizing the native Adriatic elasmobranch fauna. In 1948 (when our trawl surveys began), coastal predator communities were already depleted37,29 and demersal elasmobranchs were nearly absent on commonly trawled grounds, even on the eastern side39. Although offshore grounds remained almost unexploited until the end of WWII (Supplementary Materials), the surveyed fish community was characterized by small, productive elasmobranchs. Larger, less resilient meso-predatory species (common skates, tope sharks, angel sharks and others), which used to be common or seasonally abundant throughout the basin in the 19th and early 20th century33,40,41,42, were already scarce or under detectable levels (present in <5% of tows, Table 2, Fig. 2a) likely due to decades of directed and incidental coastal fishing33,34. Some species of low commercial value (e.g. torpedoes and eagle rays)43 might have benefited from a lower exploitation rate, but few elasmobranchs are discarded in the Adriatic if reaching a marketable size40,44,43.

The observed species-specific trends were likely not independent of changing interspecific interactions such as predator or competitor releases. Although compensatory changes in population abundances in the Adriatic were less visible than in other marine regions such as in the north west Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico12,15, some increases occurred in the least exploited eastern sectors in historical surveys (e.g. Jukic area Fig. 4a) and over long periods (e.g Zupanovic area Fig. 5). In general, competition and predation releases are more evident when not confounded by high levels of fishing mortality12. Thus, when we compared historical and more recent surveys off central Croatia (Jukic area, Fig. 5d and e), an area where offshore fishing pressure has only recently increased38, earlier population increases were later reversed or buffered such as for spurdogs and common eagle rays. Similarly, long-term patterns of change detected over the Hvar area, were different in the less exploited Croatian channels during a comparable time span. There, only thornback skate recorded a significant albeit moderate decline (−39.3% over 48 years, CI: −63.1%, −1.8%) while most of the other species increased (Zupanovic area, Fig. 5 b and c). Thus, compensatory changes might persist in relatively unexploited areas while in other parts were eventually overruled by the effects of exploitation.

Stronger predator or competitor releases might have occurred historically in the 19th and early 20th century, when large predatory sharks (e.g. hammerhead, mako, porbeagle and white sharks) were in decline37,45, but fishing had not yet expanded to industrial levels (Supplementary Methods). At that time, angel sharks, spurdogs, smooth-hounds and skates were so abundant to sustain targeted fisheries33,34 and the main Adriatic fish markets recorded increases in elasmobranch landings44,46. Such increases were particularly evident after periods of reduced fishing operations (e.g. during the two World Wars) and characterized by exceptional but not biologically plausible catches. For example, in the years immediately following the wars, D'Ancona (1949) described foot-seine hauls of 70–160 smooth-hounds averaging 10 kg a piece in Chioggia, despite the fact that it takes about 16 years for that species to reach such a size (Supplementary Methods). This may suggest compensatory population increases of residential sharks, but also possible immigration of individuals from neighbouring, less-exploited areas. Similar patterns were observed in the North Sea47 and on Georges Bank (NW Atlantic) where the rapid increase of winter skate, previously attributed to competition releases, were related to environmentally driven immigration of individuals from the northern Scotian Shelf28.

Differences in species mobility and thus exposure to exploitation are congruent with the observed patterns of resilience and depletion in the Adriatic. The high densities of bentho-pelagic elasmobranchs (spurdogs, smooth-hounds and eagle rays) in the heavily exploited upper Adriatic might partly highlight the simplistic nature of our fishing-effort model, but also a possible spillover of mobile species from the underexploited Istria to the heavily fished but extremely productive northern Italian sectors. Specific oceanographic conditions, the influence of the Po River and strong seasonal fluctuations of oceanographic regimes30 make the upper Adriatic an extremely productive area characterized by a great abundance of benthic (molluscs and crustaceans) and pelagic primary consumers (sardine and anchovies)30, which attract elasmobranchs. Devoid of pelagic larval stages, elasmobranchs disperse relying on intrinsic mobility and available ecological corridors48. The species that were dominant in the upper Adriatic can undertake transoceanic and long seasonal migrations49,48,50 and have home ranges much larger than the northern Adriatic. Hence they may be little affected by localized stressors because they are able to replenish from areas even outside the Adriatic, possibly using relatively sheltered gateways in Croatian coastal waters. Conversely, elasmobranchs with limited mobility such as catsharks and other skates (home ranges <50 km)47,49 persisted in the less-exploited eastern Adriatic and almost completely disappeared from the heavily exploited Italian waters.

In summary, the long history of human impacts severely depleted the Adriatic predator and meso-predator community, leaving the ecosystem in a structurally altered state. The elasmobranch community went through a sequence of population depletions (from great sharks in the 19th and 20th century37, to large meso-predatory elasmobranchs in the early 20th century to smaller more productive species in the later 20th) and shifts in species composition. More recently, this culminated in the near disappearance of elasmobranchs in the most exploited areas of the Adriatic Sea. Cases of ecological compensation due to release from predation or competition were not as evident as in other marine regions and may have pre-dated our observation window. Yet the strong gradient of fishing intensity from the Italian to the Croatian side allowed the persistence of a more abundant and diverse elasmobranch community in the eastern Adriatic, which may fuel a spillover of mobile species toward more exploited western areas. Similar contrasts of decline and resilience of exploited fish populations were observed in large systems of marine protected areas established on Georges Bank and the Great Barrier Reef51,52,53.

In January 2008, Croatia established a 23,870 km2 Ecological and Fisheries Protection Zone (EFPZ) in its national and international waters54. However, after 3 months, the EFPZ was dismissed because of harsh opposition of bordering countries. Our results suggest that planned and managed internationally and concerned with a reduction of fishing pressure in western areas and control of developing fisheries in the east, a similar initiative could protect abundance and diversity of Croatian resources from further depletion. Furthermore, it could promote elasmobranch recovery in the overall Adriatic by profiting from the remaining strongholds of elasmobranch abundance and diversity in the east, otherwise scarcely protected by current marine protected areas55.

Methods

Survey data and analytical outline

Our dataset comprised 2575 trawl tows, from three surveys identified as Hvar, GRUND and MEDITS, covering large portions of the basin; and two surveys, we called Jukic and Zupanovic, more locally confined to Croatian waters (Fig. 1, Table 1, Supplementary Methods and Table S1).

We initially analyzed each survey individually to avoid dealing with differences in sampling framework and gears, potentially influencing the estimated indices of abundance. We identified the available environmental and methodological covariates explaining most of the catch variability and used these variables to standardize the catches. We estimated short-term trends in catch rates from surveys having more than three years of observations and estimated long-term changes by combining historical and recent surveys in overlapping spatial domains. Finally, we attempted to explain the observed spatial and temporal patterns of the catches with data on fishing effort and species life-histories.

Catch standardization

Standardization is paramount when combining independent experimental observations (such as this set of surveys) differing in sampling framework, gear specification and survey's spatial domain (area and depth range). This process avoids inferring false population trends from observed catch trajectories. Also taking into account the inherent density, detection probability and spatial distribution of a species is necessary to prevent estimating biased indices of abundance. The low population densities of elasmobranchs and their patchy distribution generate catch distributions highly skewed, successfully described with a negative binomial distribution2,12,37.

GLMs flexibly accommodate unbalanced sampling schemes and non-normal data56. Hence using this framework, we assumed that the chance of obtaining n individuals of a species in any towi followed a negative binomial distribution with mean µi and variance  ; k is a dispersion parameter estimated from the data. We modeled log(µi) as a linear function of a number of covariates characterizing each tow, log(µi) = α + XB + log(Ai), where α is the intercept, X the matrix of covariates, B the vector of their relative parameters and Ai is the swept area, treated as an offset. Ai was usually measured by multiplying the trawl net horizontal opening (ho) by the distance towed (details in Supplementary Methods).

; k is a dispersion parameter estimated from the data. We modeled log(µi) as a linear function of a number of covariates characterizing each tow, log(µi) = α + XB + log(Ai), where α is the intercept, X the matrix of covariates, B the vector of their relative parameters and Ai is the swept area, treated as an offset. Ai was usually measured by multiplying the trawl net horizontal opening (ho) by the distance towed (details in Supplementary Methods).

For each survey, from a set of available covariates (Supplementary Methods) we selected a subset (Table 3) to construct an initial model from which we proceeded with model selection. For avoiding computational problems, arising from fitting variables with different numerical scales57, continuous variables were standardized by using unit normal scaling,  , where

, where  is the mean of variable j and sj is its standard deviation. To avoid collinearity, correlated variables were discarded or combined into predictors expressing unrelated information.

is the mean of variable j and sj is its standard deviation. To avoid collinearity, correlated variables were discarded or combined into predictors expressing unrelated information.

We needed to identify important predictors, answer ecological questions and also avoid the identification of spurious relationships resulting from over-fitting a full-saturated model (having 2n parameters, for n variables, including all interactions of main effects) to small datasets. Therefore we included only main effects and quadratic forms of some continuous variables (Table 3). Quadratic functions of depth, temperature, latitude and longitude were included to capture the tendency of animals to aggregate around optimal values of environmental variables. A quadratic function of year in MEDITS, the survey with the longest time span, was also included to model possible compensatory responses of species to changing exploitation regimes, competition or predation. Higher order temporal polynomials were not attempted, having limited temporal observation windows on animals characterized by slow population dynamics. To capture the habit of many elasmobranchs to undertake in seasonal migrations or shift in distribution58, we included a periodic function of survey date,  , where Jdi is the ordinal day for tow i (referred to the earliest date of all the surveys), which eventually allowed us to compare different surveys for tows performed at different times of the year. Substrate composition was included to account for the strong reliance of demersal species on seabed features59.

, where Jdi is the ordinal day for tow i (referred to the earliest date of all the surveys), which eventually allowed us to compare different surveys for tows performed at different times of the year. Substrate composition was included to account for the strong reliance of demersal species on seabed features59.

Model selection

From the initial model, for each species, we selected a reasonable preliminary model structure by backward elimination of covariates in SAS 9.1 (Supplementary Methods). This preliminary model was used to estimate the negative binomial dispersion parameters k to use in a second model selection stage (performed in R 2.15.060), when most variable combinations of the initial model (number is given in Table 3) were refitted by providing the estimated k's as initial values. For each model mi (variable combination) we calculated the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), AIC differences (Δi = AICi – AICmin), Akaike weights  , where R is the number of models fitted; and evidence ratios (wmax/wi)61. We then selected the best model corresponding to the minimum AIC value and the set of models with AIC differences < log(1/8) * 2 to identify a 95% confidence set (CS) of other plausible models61. We used this CS to calculate the most important variables affecting the variability of the species and the overall importance of these variables in explaining the catches of most species. To calculate the importance (w+) of a variable (xj), we summed the Akaike weights of all the models containing the variable among the CS,

, where R is the number of models fitted; and evidence ratios (wmax/wi)61. We then selected the best model corresponding to the minimum AIC value and the set of models with AIC differences < log(1/8) * 2 to identify a 95% confidence set (CS) of other plausible models61. We used this CS to calculate the most important variables affecting the variability of the species and the overall importance of these variables in explaining the catches of most species. To calculate the importance (w+) of a variable (xj), we summed the Akaike weights of all the models containing the variable among the CS,  , where Ij(mi) = 1 if variable xj is in model mi, 0 otherwise; R* is the number of models in the CS. To evaluate the overall importance of the variables across species, we first ranked the variable importance for each species from 1 (the most important, highest w+) to n (n ≤ the maximum number of covariates used in a given survey). Then we averaged the ranks across all species.

, where Ij(mi) = 1 if variable xj is in model mi, 0 otherwise; R* is the number of models in the CS. To evaluate the overall importance of the variables across species, we first ranked the variable importance for each species from 1 (the most important, highest w+) to n (n ≤ the maximum number of covariates used in a given survey). Then we averaged the ranks across all species.

Short-term trends

In Jukic and MEDITS, we estimated a species-specific instantaneous rate of change over time βy by including year among the set of standardizing covariates regardless of whether it was included in the best model. We profiled the best-model likelihood functions for a range of fixed βys (−0.9, 0.9, i.e from >99% declines to about 20,000 fold increases) and selected the value corresponding to the maximum likelihood. Obtaining within-survey trends was important to test the species' response to current exploitation levels and uncover possible compensatory community changes due to competition.

Long-term changes

We combined spatially overlapping surveys to estimate long-term changes in CPUEs for all elasmobranchs combined as well as for all sharks (including rabbit fishes), rays and individual species. We compared the tows performed in overlapping survey domains (i.e. using survey areas as Venn diagrams and comparing tows within intersections) to avoid unbalanced spatial comparisons. Of all the possible intersections, four were instrumental to evaluate changes in the species abundance and composition under different regimes of fishing: 1) in the Hvar domain (Fig. 1), we compared Hvar and MEDITS tows excluding those in MEDITS deeper than the deepest tow in Hvar (1948–2005); 2) in the Jukic domain, we compared Hvar and Jukic tows (1948–1971) and 3) Jukic and MEDITS tows (1963–2005); 4) in the Zupanovic domain, we compared Zupanovic and MEDITS tows (1957–2005). For all comparisons, we used a common glm structure with negative binomial error distribution and log link, where the expected catch per tow (µi) was a function of a categorical variable (SV) indicating whether towi was performed in the old or recent survey, the most important variables identified in the previous analytical stage and time of the year to account for seasonal differences across surveys, η = log(µi) = α + βsvSVi + βs1S1i + βs2S2i + βnNi + βeEi + βdDi + log(Ai); covariates are defined in Table 3. The initial dispersion parameters k's were those estimated in the standardization stage for the MEDITS surveys.

Effect of exploitation

If observed patterns of change in the exploited community are independent of interspecific interaction, habitat degradation or other factors affecting the population dynamics of the exploited species, we should expect a correspondence between the species' intrinsic vulnerabilities and their rates of change. Therefore we fit weighted regressions (for each short- and long-term trend analyses) between the species-specific changes in catch rates (βy and βsv) and the species' r estimated following Smith et al.9. As weights, we used the inverse of the parameter estimates' variance. Life-history parameters necessary to estimate r were collected from multiple bibliographic and electronic sources listed in the Supplementary Methods.

Similarly, as fishing intensity is spatially heterogeneous across the area, we should predict to have higher elasmobranch density in less exploited areas and vice versa. Therefore, we visually compared the spatial distribution of CPUEs (catch per unit effort) with the distribution of a predicted index of current trawl fishing intensity projected over the Adriatic. By using data on number, horse power (HP) and gross tonnage (GT) of boats fishing along the Adriatic coasts, we assumed that the intensity of fishing per unit of sea bed surface (at any point in the Adriatic Sea) was proportional to the cumulative effort exerted by all Adriatic fishing fleets, whose individual contribution depended on the distance between any point and the fleet harboring port, fleet size and point bathymetry. Using empirical data of effort distribution of a sample of four Italian trawl fleets we developed a working model predicting fishing intensity (daily units of HP per unit area) from bathymetry, distance from port and fleet size (data sources and analysis details are found in the Supplementary Methods). This analysis only provided an approximate spatial picture of fishing effort. We omitted local scale predictors of fishing intensity such as avoidance of fisheries' competition, resource abundance, compliance with spatial and seasonal management and geopolitical restrictions. Nevertheless, for our purposes of distinguishing general patterns of fishing effort between the eastern and western, northern and southern parts of the Adriatic, our analysis should provide a sufficient approximation.

References

Ferretti, F., Worm, B., Britten, G. L., Heithaus, M. R. & Lotze, H. K. Patterns and ecosystem consequences of shark declines in the ocean. Ecol. Lett. 13, 1055 –1071 (2010).

Baum, J. K. et al. Collapse and conservation of shark populations in the Northwest Atlantic. Science 299, 389–392 (2003).

Graham, K. J., Andrew, N. L. & Hodgson, K. Changes in relative abundance of sharks and rays on Australian south east fishery trawl grounds after twenty years of fishing. Mar. Freshwater Res. 52, 549–61 (2001).

Watling, L. & Norse, E. A. Disturbance of the seabed by mobile fishing gear: a comparison to forest clearcutting. Conserv. Biol. 12, 1180–1197 (1998).

Jennings, S. & Kaiser, M. J. The effects of fishing on marine ecosystems. Adv. Mar. Biol. 34, 201–212 (1998).

García, V. B., Lucifora, L. O. & Myers, R. A. The importance of habitat and life history to extinction risk in sharks, skates, rays and chimaeras. P. R. Soc. B 275, 83–89 (2008).

Myers, R. A. & Worm, B. Extinction, survival or recovery of large predatory fishes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 360, 13–20 (2005). http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/360/1453/13.full.pdf+html.

Ward-Paige, C. A., Keith, D. M., Worm, B. & Lotze, H. K. Recovery potential and conservation options for elasmobranchs. Journal of Fish Biology 80, 1844–1869 (2012).

Smith, S. E., Au, D. W. & Show, C. Intrinsic rebound potentials of 26 species of Pacific sharks. Mar. Freshwater Res. 49, 663–678 (1998).

Walker, P. A. & Hislop, J. R. G. Sensitive skates or resilient rays? Spatial and temporal shifts in ray species composition in the central and north-western North Sea between 1930 and the present day. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 55, 392–402 (1998).

Baum, J. K. & Myers, R. A. Shifting baselines and the decline of pelagic sharks in the Gulf of Mexico. Ecol. Lett. 7, 135–145 (2004).

Shepherd, T. D. & Myers, R. A. Direct and indirect fishery effects 457 on small coastal elasmobranchs in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Ecol. Lett. 8, 1095–1104 (2005).

Walker, T. Can shark resources be harvested sustainably? Mar. Freshwater Res. 49, 553–72 (1998).

Duvly, N. K., Sadovy, Y. & Reynolds, J. D. Extinction vulnerability in marine populations. Fish Fish. 4, 25–64 (2003).

Myers, R. A., Baum, J. K., Shepherd, T., Powers, S. P. & Peterson, C. H. Cascading effects of the loss of apex predatory sharks from a coastal ocean. Science 315, 1846–1850 (2007).

Hobday, D. K., Officer, R. A. & Parry, G. D. Changes to demersal fish communities in Port Phillip Bay, Australia, over two decades, 1970–91. Mar. Freshwater Res. 50, 397–407 (1999).

Dulvy, N. K., Metcalfe, J. D., Glanville, J., Pawson, M. G. & Reynolds, J. D. Fishery stability, local extinctions and shifts in community structure in skates. Conserv. Biol. 14, 283–293 (2000).

Ritchie, E. G. & Johnson, C. N. Predator interactions, mesopredator release and biodiversity conservation. Ecol. Lett. 12, 982–998 (2009).

Baum, J. K. & Worm, B. Cascading top-down effects of changing oceanic predator abundances. J. Anim. Ecol. 78, 699–714 (2009).

Wetherbee, B. M. & Cortes, E. Food consumption and feeding habits. In Carrier, ed. Biology of Sharks and their Relatives, 225–246 (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2004).

Fogarty, M. J. & Murawski, S. A. Large-scale disturbance and the sytrtucture of marine systems: fishery impacts on Georges Banl. Ecol. Appl. 8, 6–22 (1998).

Levin, P. S., Holmes, E. E., Piner, K. R. & Harvey, C. J. Shifts in a Pacific Ocean fish assemblage: the potential influence of exploitation. Conserv. Biol. 20, 1181–1190 (2006).

van der Elst, R. P. A proliferation of small sharks in the shore-based Natal sport fishery. Environ. Biol. Fishes 4, 349–362 (1979).

Pradervand, P., Mann, B. Q. & Bellis, M. F. Long-term trends in the competitive shore fishery along the KwaZulu-Natal coast, South Africa. Afr. Zool. 42, 216–236 (2007).

Heithaus, M. R., Frid, A., Wirsing, A. J. & Worm, B. Predicting ecological consequences of marine top predator declines. Trends Ecol. Evol. 4, 202–210 (2008).

Pauly, D., Christensen, V., Dalsgaard, J., Froese, R. & Torres, F. J. Fishing down marine food web. Science 279, 5352 (1998).

Rogers, S. I. & Ellis, J. R. Changes in the demersal fish assemblages of British coastal waters during the 20th century. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 57, 866–881 (2000).

Frisk, M. G., Miller, T. J., Martell, S. J. D. & Sosebee, K. New hypothesis helps explain elasmobranch “outburst” on Georges Bank in the 1980s. Ecol. Appl. 18, 234–245 (2008).

Lotze, H. K., Coll, M. & Dunne, J. Historical changes in marine resources, food-web structure and ecosystem functioning in the Adriatic Sea. Ecosystems 14, 198–222 (2011).

Pranovi, F. & Link, J. S. Ecosystem exploitation and trophodynamic indicators: A comparison between the Northern Adriatic Sea and Southern New England. Prog. Oceanogr. 81, 149–164 (2009).

Froese, R. & Pauly, D. Fishbase. World Wide Web publication (2011). URL www.fishbase.org.

Accadia, P. & Franquesa, R. The operational units approach for fisheries management in the Mediterranean Sea. Studies and Reviews. General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean. 80, 36 p., FAO, Rome (2006

Marchesetti, C. La pesca lungo le coste orientali dell'Adria. Atti Mus. Civ. Stor. Nat. Trieste 7, 1–234 (1882).

Fortibuoni, T. La Pesca in Alto Adriatico dalla Caduta della Serenissima ad Oggi: un Analisi Storica ed Ecologica. Doctoral thesis, Università degli studi di Trieste (2010).

Ferretti, F., Myers, R. A., Sartor, P. & Serena, F. Long term dynamics of the chondrichthyan fish community in the upper Tyrrhenian Sea. In: ICES. 2005. Theme session on elasmobranch fisheries science (N). ICES Document CM 2005/N:25. 25 pp. (2005).

Aldebert, Y. Demersal resources of the Gulf of Lions (NW Mediterranean). Impact of exploitation on fish diversity. Vie Milieu 47, 275–285 (1997).

Ferretti, F., Myers, R. A., Serena, F. & Lotze, H. K. Loss of large predatory sharks from the Mediterranean Sea. Conserv. Biol. 22, 952–964 (2008).

Jahutka, I. & Mišura, A. Croatian fisheries today. Tech. Rep. Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management Directorate of Fisheries (2005).

Zei, N. M. Raziskovanje s travlom na ribolovnem prodrocju vzhodnega Jadrana (Investigation with trawl in the north eastern part of the Adriatic. Contribution to the knowledge of the biology and ecology of the benthonic fishes of eastern Adriatic). Slov. Akad. Ljubljana 4, 89 (1949).

Ninni, E. Catalogo dei Pesci del Mare Adriatico (Tip. Carlo Bertotti, Venezia, 1912).

Paolucci, L. Le pescagioni nella zona Italiana del medio Adriatico. In Camera di Commercio, A. (ed.) Secondo congresso nazionale di pesca di Palermo (Dip. Maritt. Di Ancona, 1901).

Fortibuoni, T., Libralato, S., Raicevich, S., Giovanardi, O. & Solidoro, C. Coding early naturalists' accounts into long-term fish community changes in the Adriatic Sea (1800–2000). PLoS One 5, e15502 (2010).

Fortuna, C. et al. By-catch of cetaceans and other species of conservation concern during pair trawl fishing operations in the Adriatic Sea (Italy). Chem. Ecol. 26, 65–76 (2010).

D'Ancona, U. Dell'influenza della stasi peschereccia del periodo 1914–1918 sul patrimonio ittico dell'Alto Adriatico. R. Com. Talass. Ital. 126, 1–95 (1926).

McPherson, J. M. & Myers, R. A. How to infer population trends in sparse data: examples with opportunistic sighting records for great white sharks. Divers. Distrib. 15, 880–890 (2009).

D'Ancona, U. Rilievi statistici sulla pesca nell'alto Adriatico. Atti Ist. Ven. Sci. Lett. Art. 108, 41–53 (1949).

Walker, P. A. & Heessen, H. J. L. Long-term changes in ray populations in the North Sea. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 53, 1085 (1996).

Veríssimo, A., McDowell, J. R. & Graves, J. E. Global population structure of the spiny dogfish Squalus acanthias, a temperate shark with an antitropical distribution. Mol. Ecol. 19, 1651–1662 (2010).

Pawson, M. G. & Ellis, J. R. Stock identity of elasmobranchs in the Northeast Atlantic in relation to assessment and management. J. Northwest Atl. Fish. Sci. 35, 173–193 (2005).

Carrier, J. C., Musick, J. A. & Heithaus, M. R. Sharks and their Relatives 2 (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2010).

Halpern, B. S., Lester, S. E. & Kellner, J. B. Spillover from marine reserves and the replenishment of fished stocks. Environ Conserv 36, 268–276 (2010).

Murawski, S. A., Brown, R., Lai, H. L., Rago, P. J. & Hendrickson, L. Large-scale closed areas as a fishery-management tool in temperate marine systems: the Georges Bank experience. Bull. Mar. Sci. 66, 775–798 (2000).

McCook, L. J. et al. Adaptive management of the Great Barrier Reef: A globally significant demonstration of the benefits of networks of marine reserves. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 18278–18285 (2010).

Vidas, D. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, the European Union and the Rule of Law: What is going on in the Adriatic Sea? FNI Report 12/2008, Fridtjof Nansen Institute. (2008

Sala, E. et al. The structure of mediterranean rocky reef ecosystems across environmental and human gradients and conservation implications. PLoS ONE 7, e32742 (2012).

McCullagh, P. & Nelder, J. A. Generalized Linear Models, vol. 37 of Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability (Chapman & Hall/CRC, 1999), second edn.

Zuur, A., Ieno, E., Walker, N., Saveliev, A. & Smith, G. Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R (Springer Verlag, 2009).

Walker, P., Howlett, G. & Millner, R. Distribution, movement and stock structure of three ray species in the North Sea and eastern English Channel. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 54, 797 (1997).

McConnaughey, R. A. & Syrjala, S. E. Statistical relationships between the distributions of groundfish and crabs in the eastern Bering Sea and processed returns from a single-beam echosounder. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 66, 1425–1432 (2009).

R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria (2012). URL http://www.R-project.org/.

Burnham, K. P. & Anderson, D. R. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: a Practical Information-Theoretic Approach (Springer, New York, 2002).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank P. Casale for providing data on empirical effort distribution, the Italian Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry for granting permission to use MEDITS data, C. Piccinetti for providing MEDITS data and W. Blanchard and E. Susko for statistical advice, F. Serena for sharing data on trawl performances and discussions, F. Micheli, C. Mora, N. Dulvy, G. De Leo, Chris Fehily and Lauren Daly for comments and discussions. Financial support was provided by the Lenfest Ocean Program and the Oak Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.F., G.C.O. and H.K.L. conceived and designed the study; F.F., G.C.O. and C.J.J. collected and analyzed the data; F.F., G.C.O., A.A.R. and H.K.L. wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods and Results

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ferretti, F., Osio, G., Jenkins, C. et al. Long-term change in a meso-predator community in response to prolonged and heterogeneous human impact. Sci Rep 3, 1057 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01057

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01057

This article is cited by

-

Influence of ecological traits on spatio-temporal dynamics of an elasmobranch community in a heavily exploited basin

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Small-scale fisheries catch more threatened elasmobranchs inside partially protected areas than in unprotected areas

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Odontocete cetaceans foraging behind trawlers, worldwide

Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries (2022)

-

Food web model to assess the fishing impacts and ecological role of elasmobranchs in a coastal ecosystem of Southern Brazil

Environmental Biology of Fishes (2021)

-

Life-history traits of the marbled electric ray, Torpedo marmorata Risso, 1810, from the Greek Seas, north-eastern Mediterranean Sea

Environmental Biology of Fishes (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.