Abstract

The salient feature of liquid crystal elastomers and networks is strong coupling between orientational order and mechanical strain. Orientational order can be changed by a wide variety of stimuli, including the presence of moisture. Changes in the orientation of constituents give rise to stresses and strains, which result in changes in sample shape. We have utilized this effect to build soft cellulose-based motor driven by humidity. The motor consists of a circular loop of cellulose film, which passes over two wheels. When humid air is present near one of the wheels on one side of the film, with drier air elsewhere, rotation of the wheels results. As the wheels rotate, the humid film dries. The motor runs so long as the difference in humidity is maintained. Our cellulose liquid crystal motor thus extracts mechanical work from a difference in humidity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cellulose is the most common organic compound on earth. It is the structural component of the cell walls of green plants, constituting about a third of all plant matter. It is a polysaccharide, the linear polymer  , where

, where  . Because of its ubiquity and importance, considerable attention has been given to its study and characterization1. In addition to paper products, it is used to produce cellophane, rayon and gunpowder and well as adhesives, thickeners and stabilizers. It is also an additive to prevent caking of parmesan cheese powders.

. Because of its ubiquity and importance, considerable attention has been given to its study and characterization1. In addition to paper products, it is used to produce cellophane, rayon and gunpowder and well as adhesives, thickeners and stabilizers. It is also an additive to prevent caking of parmesan cheese powders.

Hydroxypropylcellulose (HPC) is a commercially available derivative of cellulose in which some of the hydroxyl groups in the repeating glucose units have been hydroxypropylated. The structure is shown in Fig. 1a. Due to the presence of both hydrophobic and hydrophilic groups, it has a lower critical solution temperature than cellulose; below 45°C, it is water-soluble. It is biodegradable, biocompatible and electroneutral, well suited for pharmaceutical and food applications as thickeners, emulsifiers and encapsulators2. It is also used in artificial tears.

Molecular structure and thin film preparation.

(a) Idealized chemical structure of hydroxypropylcellulose (HPC), R-CH2CH(OR')CH3 or -H (R′- H or -CH2CH(OH)CH3), with an average degree of substitution of 3.5. (b) Schematic of apparatus used to produce HPC shear cast films from lyotropic liquid crystalline solutions, with different thicknesses (range 30–100 μm) depending on the Gardner knife gap and velocity. (c) 3D topographic image (23 × 23 μm2 scan) of the free surface of a sheared HPC film.

Aqueous HPC solutions are isotropic at low polymer concentrations, typically consisting of separate polymer chains in the solvent. At higher concentrations, the hydrophobic hydroxypropyl groups promote the association of polymer chains to form rigid rod-like fragments3. The chains in the fragments are made rigid by intramolecular hydrogen bonding of the side chain hydroxylpropyl groups and are held together by intermolecular hydrogen bonds and London dispersion forces. The molecules are packed into crystallites ~470 Å long and ~34 Å diameter4. These micro-fibrils, in turn, associate to form supermolecular rod-like fragments, resulting in a network of rigid rod-like fragments joined together by flexible polymer linkages. As the polymer concentration is increased, the increasingly densely packed rodlike fragments become parallel and liquid crystal mesophases are formed5.

Liquid crystals (LCs) are liquids with orientationally ordered constituents. Their broken continuous symmetry gives rise to low energy excitations - Goldstone modes. Consequently, LCs are exceptionally responsive to external stimuli, enabling LCD technology as well as other novel applications6. Simple nematic orientational order is characterized by a tensor order parameter  , where

, where  is a component of a unit vector

is a component of a unit vector  along the symmetry axis of a mesogenic molecule or particle; the brackets denote ensemble average. Physical properties, such as the density, dielectric permittivity and magnetic permeability, are functions of

along the symmetry axis of a mesogenic molecule or particle; the brackets denote ensemble average. Physical properties, such as the density, dielectric permittivity and magnetic permeability, are functions of  . In a uniaxial system, the order parameter may be written as

. In a uniaxial system, the order parameter may be written as  , where

, where  is a scalar order parameter and

is a scalar order parameter and  is the nematic director, a unit vector along the direction of average alignment.

is the nematic director, a unit vector along the direction of average alignment.

Elastomers are rubber-like solids characterized by an elastic modulus on the order of MPa which can accommodate strains >100%. In 1975, P.G. de Gennes proposed the concept of liquid crystal elastomers (LCEs), cross-linked polymer networks with orientationally ordered mesogenic units7. LCE materials were synthesized and samples produced for the first time by H. Finkelmann8. The key aspect of these new ‘solid’ liquid crystals is coupling between mechanical strain,  and orientational order,

and orientational order,  . Due to the symmetry allowed scalar

. Due to the symmetry allowed scalar  which appears in the free energy, an applied strain will change orientational order, similarly to an applied electric field and all physical properties which depend on it. More importantly for the work reported here, any change in orientational order will result in mechanical strain, similar to that resulting from external stress, causing a change in the shape of the elastomer sample. Due to their unusual behavior, LCEs have received considerable attention, their salient features are discussed in detail in Refs. 9,10. Changes in the order parameter caused by heating, illumination, exposure to electric fields or the presence of chemical solvents give rise to corresponding changes in sample shape11,12,13,14. The mesogenic units may be incorporated into the polymer main chain, or they can be attached via side-chains. In main chain LCEs, the increase of nematic order leads to an increase in sample length along the director and a contraction in the two perpendicular directions. A decrease in order has the converse effect.

which appears in the free energy, an applied strain will change orientational order, similarly to an applied electric field and all physical properties which depend on it. More importantly for the work reported here, any change in orientational order will result in mechanical strain, similar to that resulting from external stress, causing a change in the shape of the elastomer sample. Due to their unusual behavior, LCEs have received considerable attention, their salient features are discussed in detail in Refs. 9,10. Changes in the order parameter caused by heating, illumination, exposure to electric fields or the presence of chemical solvents give rise to corresponding changes in sample shape11,12,13,14. The mesogenic units may be incorporated into the polymer main chain, or they can be attached via side-chains. In main chain LCEs, the increase of nematic order leads to an increase in sample length along the director and a contraction in the two perpendicular directions. A decrease in order has the converse effect.

Polymer networks are structurally similar to elastomers, but due to higher cross-link density, their modulus is in the GPa range. Liquid crystal networks (LCNs) show similar behavior to LCEs in their response to excitations, except they are much stiffer. Although typically the orientationally ordered constituents of LCs are molecules, they may also be electron states15, or nano-16 or micro-17 particles. In the case of HPC, the orientationally ordered constituents are the mesogenic rigid fragments18. HPC films behave, as LCNs; their remarkable response to stimuli, discussed below, is the result of liquid crystallinity of the rod-like fragments and the coupling of orientational order to mechanical strain.

Results

Anisotropic HPC films are formed by the evaporation of water from liquid crystalline aqueous HPC solutions (60% w/w). In preparing samples, solutions are initially on a glass substrate, with a free surface exposed to air. When the cellulose concentration is sufficiently high for the formation of the liquid crystal phase, the mesogenic fragments can be uniformly aligned in the sample by shear. Shear is applied via a calibrated Gardner knife moving at a controlled speed of 1.25 mm s−1 on the free surface, as shown in Fig. 1b.; the process produces a monodomain nematic sample. As indicated by X-ray studies19, the director aligns along the shear direction. As evaporation continues, the density of rod-like fragments increases near the free top surface, giving rise to increased orientational order. This in turn causes elongation at the top of the film in the direction parallel to the director and since the dimensions of the bottom surface in contact with the glass substrate are fixed, the top surface buckles, forming a set of grooves20. This can also be seen in Fig. 1c. The final film thickness is ~40 μm microns. The grooves, whose wave vector is along the shear direction, are ~3 μm apart, with amplitude ~45 nm. The structure of the film near the glass surface is less well understood. Here, the solvent remains during shear, so less alignment is expected. The films, removed from the substrate, are large area, free-standing flexible macroscopic samples.

The modulus of the cellulose network has been measured for strain along the director, as well as perpendicular to it. Results are shown in Fig. 2; for small strains, Young's modulus is  for shear parallel and

for shear parallel and  perpendicular to the director. Above a threshold of

perpendicular to the director. Above a threshold of  , the stress in the perpendicular direction is nearly independent of the strain. This ‘semi-soft’ elastic response is characteristic of liquid crystal elastomers9. When exposed to water vapor, free standing films prepared from a 60% w/w solution bend, as shown in Fig. 3. When water vapor penetrates the free surface of the film, the sample bends around an axis parallel to the shear direction, with the free surface on the outside (Fig. 3a.). This is consistent with expansion of the free surface of the film in the direction perpendicular to the director. Such an expansion is expected, since the order parameter is reduced by the presence of the solvent water and furthermore the presence of water molecules between the cellulose chains in the rigid segments is expected to cause the thickness of the rod-like fragments to increase.

, the stress in the perpendicular direction is nearly independent of the strain. This ‘semi-soft’ elastic response is characteristic of liquid crystal elastomers9. When exposed to water vapor, free standing films prepared from a 60% w/w solution bend, as shown in Fig. 3. When water vapor penetrates the free surface of the film, the sample bends around an axis parallel to the shear direction, with the free surface on the outside (Fig. 3a.). This is consistent with expansion of the free surface of the film in the direction perpendicular to the director. Such an expansion is expected, since the order parameter is reduced by the presence of the solvent water and furthermore the presence of water molecules between the cellulose chains in the rigid segments is expected to cause the thickness of the rod-like fragments to increase.

Stress-strain relations.

Squares correspond to strain parallel to the shear direction and the nematic director. Circles correspond to strain perpendicular to the shear direction and the nematic director. For this geometry, above a threshold, the stress is nearly independent of strain. This indicates ‘semi-soft’ elasticity, characteristic of nematic elastomers. The negative slope at higher strains corresponds to failure due to tearing of the films.

The shear stress associated with such bend has been measured, as a function of time (Fig. 4), in a 20 mm × 20 mm × 32 μm planar sample at 24°C with free surface exposed to humidity. Measurements were taken with Mettler Toledo AG204 load sensor. The maximum stress measured was 383 Pa.

When the film is allowed to dry, either by heating or by being placed in a low-humidity environment, the film unbends, reversibly assuming its original shape. The bending is relatively fast, on the scale of ~1 s.

Interestingly, when the glass side of the film is exposed to water vapor, it bends around an axis perpendicular to the shear direction, with the glass side being convex (Fig. 3b.). This is consistent with a nearly isotropic expansion of the glass side surface due to the presence of moisture. Since corrugations on the free surface give rise to a smaller effective modulus for bend in this direction, as has been confirmed by independent measurements, bend occurs around an axis perpendicular to the shear direction. The bend produced by exposing the glass side to water vapor is considerably smaller than that of the free surface.

Water vapor induced bend has been demonstrated in DNA covered Si cantilevers21, as well as in a different LCN system with a different geometry by Broer et al.14. In this work, we have exploited such a bending phenomenon to produce a humidity driven rotary motor.

There exist a wide variety of definitions of motors in the literature. We choose here to define a motor as a device, which uses energy, but not momentum, to produce motion. Engines may be defined as motors, which obtain energy from a fuel.

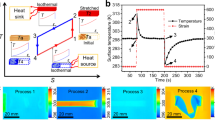

Our humidity driven motor is shown below. A monodomain nematic HPC film was produced in the form of a circular loop, 8.0 cm long and 1.0 cm wide (Fig. 5). The alignment direction is in the plane of the film, perpendicular to the long edges. The loop was passed over two 14 mm diameter wheels with horizontal axes. When humid air was applied to the outer side of the film near one of the wheels, as shown in Fig. 5, the wheels began to rotate and continued so long as humid air was present. The motion is caused by humidity-induced bend of the liquid crystalline HPC film. A heuristic explanation for the motion is as follows. If the tension in the film is assumed to be nearly uniform, the humidity induced bend shortens the lever arm on the side where the moist air is applied, resulting on a net torque on the wheel and causing rotation of the wheel as illustrated schematically in Fig. 6. We have estimated the tensile stress from the shape of the circular film loop to be  , which is close to the shear stress produced by humidity. We conjecture that these two quantities need to be comparable for the engine to operate efficiently.

, which is close to the shear stress produced by humidity. We conjecture that these two quantities need to be comparable for the engine to operate efficiently.

Moisture-driven liquid crystal cellulose engine.

(a) Schematic of the motor, showing location of moist air and rotation direction. The alignment direction is parallel to the axes of the wheels. The free surface of the film is on the outer side. (b) Series of video frames showing rotation. (Movie of the motor is available under supplementary materials.) The motor is housed in a dry environment. Momentum transfer from the moist air is small and opposes the observed motion. Belt dimensions are: 1.0 cm × 8.0 cm × 30 μm; wheel dia. is 14 mm. The direction of rotation is indicated by a black arrow and of moist air flow by a white arrow (a). In (b), t = 2 s/frame.

Schematic of the humidity induced bending mechanism.

(a) The configuration is symmetric about a vertical axis. The lever arms (green) are of equal length and the net torque on the top wheel due to tension in the film is zero. (b) Due to the humidity-induced bend, the configuration is no longer symmetric. Lever arm on the right in top wheel is shorter; net torque on top wheel due to tension in the film gives rise to CW rotation. (The humidity induced bend has been exaggerated to aid the illustration.)

As the motor rotates, the humid film dries. Key to the process is the spontaneous curvature of the film in the region near the wheel where the humidity is applied. The motor can be made to rotate faster if the ambient temperature is increased, or, equivalently, if the ambient humidity is reduced. A detailed model will be published elsewhere.

Discussion

The energy to drive the motor comes from water vapor – from “steam”. In conventional steam engines, fuel is burned to heat the water, raising the chemical potential of the water vapor due to increase in the temperature. Free energy is converted into work by the engine. Our steam engine exploits the difference in chemical potential of water molecules in humid and in dry air; the LCN belt transports the water from regions of high chemical potential to low, gaining energy in the process. The difference in chemical potential μ is given by22

where k is Boltzmann's constant, T is the absolute temperature and χ is the relative humidity. If the relative humidities are 30% and 70%, as in our experiments, the amount of energy available for work at room temperature is 2.1 KJ/mole of water, or approximately 100 J/g. The underlying mechanism is similar to that of the collagen engine of Katchalsky23, which is driven by the chemical potential difference of NaCl in saline solutions and pure water. Whereas his collagen fibers contracted in the presence of salt, our LCN bends in the presence of humidity. Since our steam engine runs isothermally, it differs fundamentally from conventional steam engines in that it is not a heat engine. We call it therefore a steam engine of the second kind and note that, consequently, its efficiency not limited by that of Carnot cycles. It appears, from Eq. (1), that considerable energy is available for work from reservoirs of high and low humidity; our engine provides a new method of obtaining work from a humidity difference.

In summary, we have demonstrated a new type of soft motor, using a cellulose liquid crystal film, driven by a difference in humidity. The motor is simple; it relies on the moisture-induced bend of the HPC, which arises from the coupling between the orientation order of the rigid rod-like fragments of the network and mechanical strain. Changes in orientational order are caused by the absorption of water molecules. As the engine rotates, the moist film dries in a dry air environment and returns to its original shape, ready to perform work again when exposed to moist humidity. Since the transport of water is via directed diffusion along concentration gradients, it is expected that smaller motors will run faster. Micromotors operating on this principle, using the chemical potential of liquid water or moist air may be useful in reducing humidity or producing mechanical or electrical energy. Further studies are needed to determine the efficiency of the energy conversion process in such a steam engine of the second kind.

Methods

(Hydroxypropyl)cellulose (HPC) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich ( = 100.000 g/mol; molar substitution,

= 100.000 g/mol; molar substitution,  = 3.5, as determined by 1H NMR) and used as received. Solutions of HPC in distilled water with concentration of 60% (w/w) were prepared at room temperature. After the first week they were stirred every other day and kept, away from light, for at least 4 weeks, until used.

= 3.5, as determined by 1H NMR) and used as received. Solutions of HPC in distilled water with concentration of 60% (w/w) were prepared at room temperature. After the first week they were stirred every other day and kept, away from light, for at least 4 weeks, until used.

Films were prepared from LC solutions, casted and sheared simultaneously by moving a calibrated Gardner knife from Braive Instruments at 1.25 mm s−1. The films were allowed to dry at room temperature and were kept in a (20%) controlled humidity chamber until used. The thickness of the dried films was estimated by averaging 10 measurements with a Mitutoyo digital micrometer.

To construct the motor, the cellulosic film was produced in the form of a circular loop, 8.0 cm long, 1.0 cm wide, which passes over two 14 mm diameter wheels.

The water vapor was generated by an AirProject ultrasonic humidifier (Italy ARTSANA Group).

Photographs and movie of the cellulosic film and motor were taken with a Casio EX-F1 Exilim Pro and Canon EOS 550D photo camera. Blender, version 2.57b, was used to obtain the 3D draw of the shear-casting knife and motor.

Change history

01 July 2013

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

References

Jarvis, M. Chemistry: cellulose stacks up. Nature 426, 611–612 (2003).

Kondo, T. in Polysaccharides (ed Dumitriu S.) (Marcel Dekker, New York, 2005).

Evmenenko, G., Yu, C. J., Kewalramani, S. & Dutta, P. Structural reorganization in films of cellulose derivatives in the presence of colloidal particles. Polymer 45, 6269–6273 (2004).

Samuels, R. J. Solid-State Characterization of Structure and Deformation Behavior of Water-Soluble Hydroxypropylcellulose. J Polym Sci A2 7, 1197–& (1969).

Patra, A., Verma, P. K. & Mitra, R. K. Slow relaxation dynamics of water in hydroxypropyl cellulose-water mixture traces its phase transition pathway: a spectroscopic investigation. The journal of physical chemistry. B 116, 1508–1516 (2012).

Palffy-Muhoray, P. The diverse world of liquid crystals. Physics Today 60, 54–57 (2007).

Gennes, P. G. d., Chung, T. C. & Petchsux, A. Réflexions sur un type de polymères nématiques. C.R. Acad. Sci. Ser. B 281, 101–103 (1975).

Finkelmann, H., Kock, H. & Rehage, G. Investigations on LC polysiloxanes: 3. Liquid crystalline elastomers - a new type of liquid crystalline material. Makromolekulare Chemie, Rapid Communications 2, 317–322 (1981).

Warner, M. & Terentjev, E. M. Liquid crystal elastomers. (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2007).

Liquid crystal elastomers: materials and applications. (Springer, New York, 2012).

Kupfer, J. & Finkelmann, H. Liquid-Crystal Elastomers - Influence of the Orientational Distribution of the Cross-Links on the Phase-Behavior and Reorientation Processes. Macromol Chem Physic 195, 1353–1367 (1994).

Yu, Y. L., Nakano, M. & Ikeda, T. Directed bending of a polymer film by light - Miniaturizing a simple photomechanical system could expand its range of applications. Nature 425, 145–145 (2003).

Urayama, K., Honda, S. & Takigawa, T. Electrooptical effects with anisotropic deformation in nematic gels. Macromolecules 38, 3574–3576 (2005).

Harris, K. D., Bastiaansen, C. W. M. & Broer, D. J. A glassy bending-mode polymeric actuator which deforms in response to solvent polarity. Macromol Rapid Comm 27, 1323–1329 (2006).

Tanatar, M. A., Paglione, J., Petrovic, C. & Taillefer, L. Anisotropic violation of the Wiedemann-Franz law at a quantum critical point. Science 316, 1320–1322 (2007).

Shopsowitz, K. E., Qi, H., Hamad, W. Y. & Maclachlan, M. J. Free-standing mesoporous silica films with tunable chiral nematic structures. Nature 468, 422–425 (2010).

Tkalec, U., Ravnik, M., Copar, S., Zumer, S. & Musevic, I. Reconfigurable knots and links in chiral nematic colloids. Science 333, 62–65 (2011).

Werbowyj, R. S. & Gray, D. G. Optical-Properties of (Hydroxypropyl)Cellulose Liquid-Crystals - Cholesteric Pitch and Polymer Concentration. Macromolecules 17, 1512–1520 (1984).

Godinho, M. H. et al. Liquid crystalline cellulose derivative elastomer films under uniaxial strain. Cellulose 16, 199–205 (2009).

Godinho, M. H., Fonseca, J. G., Ribeiro, A. C., Melo, L. V. & Brogueira, P. Atomic force microscopy study of hydroxypropylcellulose films prepared from liquid crystalline aqueous solutions. Macromolecules 35, 5932–5936 (2002).

Mertens, J. et al. Label-free detection of DNA hybridization based on hydration-induced tension in nucleic acid films. Nat Nanotechnol 3, 301–307 (2008).

Abraham, N. & Palffy-Muhoray, P. A dunking bird of the second kind. Am J Phys 72, 782–785 (2004).

Steinberg, I. Z., Oplatka, A. & Katchalsky, A. Mechanochemical Engines. Nature 210, 568–571 (1966).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from the Portuguese Science and Technology Foundation through grants SFRH/BD/63574/2009, SFRH/BPD/78430/2011 to Y. Geng and S.N. Fernandes respectively, projects PTDC/CTM/099595/2008, PTDC/FIS/110132/2009, PEst-C/CTM/LA0025/2011 (Strategic Project - LA 25 - 2011–2012) and from the U.S. National Science Foundation IIP 1114332.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.G., P.L.A. and S.N. prepared samples and worked on developing the motor. C.C. worked on optimizing the motor. P.P.-M. and M.H.G. conceived of and directed the project and wrote this paper; they contributed equally to this work.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Geng, Y., Almeida, P., Fernandes, S. et al. A cellulose liquid crystal motor: a steam engine of the second kind. Sci Rep 3, 1028 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01028

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01028

This article is cited by

-

Moisture-responsive films of cellulose stearoyl esters showing reversible shape transitions

Scientific Reports (2015)

-

Scaling up nanoscale water-driven energy conversion into evaporation-driven engines and generators

Nature Communications (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.