Abstract

Electron reflection at an interface is a fundamental quantum transport phenomenon. The most famous electron reflection is the electron→hole Andreev reflection (AR) at a metal/superconductor interface. While AR can be either specular or retro-type, electron→electron reflection is limited to only the specular type. Here we show that electrons can undergo retro-reflection in bilayer graphene (BLG). The underlying mechanism for this previously unknown process is the anisotropic constant energy band contour of BLG. The electron group velocity is fully reversed upon reflection, causing electrons to be retro-reflected. Utilizing a BLG/superconductor junction (BLG/S) as a model structure, we show that the unique low energy quasiparticle nature of BLG results in two striking features: (1) AR is completely absent, making BLG/S 100% electron reflective; (2) electrons are valley-selectively focused upon retro-reflection. Our results suggest that BLG/S is a valley-selective Veselago electron focusing mirror which can be useful in valleytronic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Specular reflection of a particle by smooth solid wall is a classic textbook illustration on the principle of conservation of momentum1. Because the particle motion is intrinsically ‘locked’ to the direction of the momentum, the conservation of momentum parallel to the interface, ky, automatically implies the group velocity component parallel to the interface, vy, to remain unchanged upon reflection. This results in specular reflection (Fig. 1a). In the quantum mechanical case, retro reflection can occur at a superconducting interface via Andreev reflection (AR)2. AR is a two particle process in which an incident electron in the normal metal couples with another electron below the Fermi level to form a Cooper pair, crossing the interface into the superconductor3 and leaving behind a hole. Since the hole is a time reversed version of the incident electron, its vy is anti-parallel with ky. The conservation of ky requires a sign reversal of vy upon reflection. This results in electron→hole retro reflection. In graphene4 and a 2D semiconductor with Rashba spin-orbit coupling5, the pseudo-spin (graphene) and real-spin (Rashba semiconductor) nature of the two systems creates an additional ‘spin’-split branch: up-down Dirac cones in graphene and left-right sub-bands in the Rashba semiconductor. When forming an interface with a superconductor, the split branches form two ‘flavors’ of holes: one with ky parallel with vy and one with ky anti-parallel with vy. This allows both retro and specular AR to occur in these systems.

(a) Since electron group velocity component vy is locked to the momentum component ky, conservation of ky allows only specular electron reflection (SER) to occur; (b) retro electron reflection (RER) requires vy to be ‘unlocked’ from ky such that reversal of vy can still occur while conserving ky; (c) constant energy slice of a parabolic (or linear) energy spectrum.

The circular band contour allows only SER to occur; (d) constant energy slice of a hypothetical energy spectrum with boomerang-shaped band contour. The constant energy band contour of the incident states in k-space is convex while that of the reflected states is concave. The opposite band contours between incident and reflected states causes the sign reversal of vy upon reflection. This results in RER.

Retro reflection of electrons at an interface remains elusive. For retro electron reflection (RER) to occur, reversal of vy is required but this, however, violates the momentum conservation principle. To achieve RER, vy needs to be ‘unlocked’ from ky such that the direction of vy can be freely reversed upon reflection while conserving ky (Fig. 1b). We define a constant energy band contour as the outline of the energy spectrum across a constant energy slice in k-space. The concept of constant energy band contours will be useful in the qualitative understanding of the electron reflection trajectory, since it is directly related to the electron group velocity. Fig 1c shows the circular band contour of a parabolic (or linear) energy spectrum. In this case, specular electron reflection (SER) is the only permissible electron→electron reflection process since vy does not change sign upon reflection. We articulate that (i) anisotropic and (ii) opposite band contour for incident and reflected electron states are the fundamental criteria for an electron to be retro-reflected. Criterion (i) allows the electron motion to be unlocked from the direction of momentum since in an anisotropic band contour, the momentum no longer aligns with the group velocity while the direction of the group velocity is solely determined by the contour of the band via  . Criterion (ii) allows the direction of vy to be reversed upon reflection. In Fig. 1d, a hypothetical energy spectrum with boomerang-shaped constant energy band contour in k-space is shown. The boomerang-shaped constant energy band contour is highly anisotropic in k-space. The constant energy band contour of the incident states is convex while that of the reflected states is concave. Along a constant line of ky, the reflected electron motion is completely reversed in both x- and y-direction. vy is reversed while conserving ky. The reflection process is hence RER.

. Criterion (ii) allows the direction of vy to be reversed upon reflection. In Fig. 1d, a hypothetical energy spectrum with boomerang-shaped constant energy band contour in k-space is shown. The boomerang-shaped constant energy band contour is highly anisotropic in k-space. The constant energy band contour of the incident states is convex while that of the reflected states is concave. Along a constant line of ky, the reflected electron motion is completely reversed in both x- and y-direction. vy is reversed while conserving ky. The reflection process is hence RER.

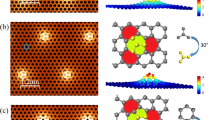

The boomerang-shaped constant energy band contour occurs in a Bernal-stacked bilayer graphene (BLG). The low energy spectrum of BLG exhibits the trigonal warping effect (TW), i.e. the energy spectrum splits into four discrete low energy pockets which join to form a single-band at higher energy6. The TW has resulted in highly anisotropic constant energy band contour which fulfills both of the RER criteria. In the tight-binding framework, the low energy effective Hamiltonian is given as

where ξ = 1(−1) for K (K′) valley, ε0 = (v3/vF)2γ1, k± = kx ± iky. The wave vectors are normalized by k0 and are dimensionless, i.e. kx ≡ kx/k0, ky ≡ ky/k0 where  . The hopping parameters are γ1 = 0.3 eV, v3/vF = 0.1 and vF = 106 m/s6. The characteristic wave vector k0 defines the phase-space separation between central and satellite Dirac points. The low energy pockets join to form a single trigonally warped band structure at εk = ε0/4. The quadratic term in Eq. (1) represents the indirect electron hopping between B↑ and A↓ sublattices (↑ and ↓ denote upper and lower layer respectively) mediated by A↑-B↓ dimer pair while the linear term represents the weak direct electron hopping between the B↑ and A↓ side (Fig. 2a). The inclusion of the linear term anisotropically deforms the low energy dispersion:

. The hopping parameters are γ1 = 0.3 eV, v3/vF = 0.1 and vF = 106 m/s6. The characteristic wave vector k0 defines the phase-space separation between central and satellite Dirac points. The low energy pockets join to form a single trigonally warped band structure at εk = ε0/4. The quadratic term in Eq. (1) represents the indirect electron hopping between B↑ and A↓ sublattices (↑ and ↓ denote upper and lower layer respectively) mediated by A↑-B↓ dimer pair while the linear term represents the weak direct electron hopping between the B↑ and A↓ side (Fig. 2a). The inclusion of the linear term anisotropically deforms the low energy dispersion:  where φ is the momentum angle and ξ = ± is the valley-index. For simplicity, we denote εk ≡ εk,+ for the K-valley. The BLG energy spectrum exhibits three distinct categories of band contour (Fig. 2b): (A) the band structure splits into four distinct low energy ‘pockets’ at εk < ε0/4; (B) the pockets join to form a single band with ‘three-leaf’-like contour at ε0/4 < εk < 10.9ε0; and (C) the band contour becomes parabolic-like in the high energy regime of εk > 10.9ε0. Regime (B) is the most interesting since the reflection process is dominantly RER. The ‘three-leaf ’-shaped band contour is highly anisotropic. The incident electron states residing on the right-pointing ‘leaf ’ and the right-edges of the upper and lower leaves has a convex constant energy band contour while the reflected electron residing on the left-hand edge of the upper and lower leaves has a concave constant energy band contour. As shown in Fig. 2c, an incident electron with direction of motion pointing upwardly-right (red arrow) is reflected as an electron pointing downwardly-left (green arrow) along a constant line of ky. The reversal of vy while conserving ky results in RER. SER occurs only at large |ky| in which criteria (ii) no longer holds (incident and reflected electrons has the same constant energy band contour and hence vy does not change sign upon reflection). The very low energy regime (A) and high energy regime (C) are less ideal for RER. In Regime (A), RER occurs only minimally in the upper and lower pockets. In regime (C), the quadratic term in Eq. (1) dominates and the constant energy band contour loses the required boomerang-shaped constant energy band contour.

where φ is the momentum angle and ξ = ± is the valley-index. For simplicity, we denote εk ≡ εk,+ for the K-valley. The BLG energy spectrum exhibits three distinct categories of band contour (Fig. 2b): (A) the band structure splits into four distinct low energy ‘pockets’ at εk < ε0/4; (B) the pockets join to form a single band with ‘three-leaf’-like contour at ε0/4 < εk < 10.9ε0; and (C) the band contour becomes parabolic-like in the high energy regime of εk > 10.9ε0. Regime (B) is the most interesting since the reflection process is dominantly RER. The ‘three-leaf ’-shaped band contour is highly anisotropic. The incident electron states residing on the right-pointing ‘leaf ’ and the right-edges of the upper and lower leaves has a convex constant energy band contour while the reflected electron residing on the left-hand edge of the upper and lower leaves has a concave constant energy band contour. As shown in Fig. 2c, an incident electron with direction of motion pointing upwardly-right (red arrow) is reflected as an electron pointing downwardly-left (green arrow) along a constant line of ky. The reversal of vy while conserving ky results in RER. SER occurs only at large |ky| in which criteria (ii) no longer holds (incident and reflected electrons has the same constant energy band contour and hence vy does not change sign upon reflection). The very low energy regime (A) and high energy regime (C) are less ideal for RER. In Regime (A), RER occurs only minimally in the upper and lower pockets. In regime (C), the quadratic term in Eq. (1) dominates and the constant energy band contour loses the required boomerang-shaped constant energy band contour.

(a) Bernal-stacked bilayer graphene lattice structure; (b) the energy spectrum contour plot in phase space, showing three distinct energy regime: Regime (A): εk < ε0/4, Regime (B): ε0/4 < εk < 10.9ε0 and Regime (C): εk > 10.9ε0.

Retro electron reflection occurs optimally in Regime (B) due to its ‘boomerang-like’ anisotropic constant energy band contour in k-space. In high energy Regime (C), retro reflection is no longer possible as the band contour becomes parabolic-like; (c) Band contour of an constant energy slice in Regime (B). The green and blue arrows denotes incident and reflected electron direction of motion respectively. The opposite band contour between incident (convex) and reflected states (concave) causes vy to reverse its direction upon reflection, leading to RER.

In this work, we utilize a hybrid junction made up of a bilayer graphene and a superconductor (BLG/S) to theoretically demonstrate the unusual RER phenomena. The RER in BLG/S represents one last missing piece in the quantum transport phenomena of a superconducting interface where specular reflection of electrons and retro and specular reflection of holes have all been demonstrated4,5,7,8,9,10,11. Not only RER occurs in such a junction, there are two additional surprises: (1) the 2π Berry phase of the BLG low energy electron forbids its transmission across the junction, resulting in the complete absence of AR; and (2) electron reflection in BLG/S is valley-dependent. The BLG/S acts as a valley-selective Veselago electron-mirror.

Results

Determination of electron reflection type using group velocities

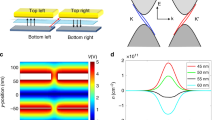

In the usual cases (parabolic or linear band structure), quasi-momentum angle φ = tan−1 (ky/kx) is commonly used to described particle trajectory. Each φ uniquely defines a particle traveling in the direction of φ. In BLG, φ is no longer locked to the electron motion due to the constant energy band contour anisotropy. Instead, the electron trajectory is more accurately described by group velocity angle θ = tan−1 (vy/vx). Unlike φ, the uniqueness of θ is lost. Each θ can simultaneously represent several electron states and hence becomes ambiguous. We therefore characterize the reflection problem by momentum component ky instead of the incident quasi-momentum angle θ or incident group velocity angle φ. The group velocity is given as  where ν = x, y denotes x- and y-directional group velocity respectively. We consider the case where the reflection interface is placed along the y-direction. In Fig. 3a–c, vx of incident and reflected electrons across a constant energy slice are shown. vx has the opposite sign between incident electron and reflected electron and is highly asymmetric due to the broken left-right symmetry of the BLG band contour.

where ν = x, y denotes x- and y-directional group velocity respectively. We consider the case where the reflection interface is placed along the y-direction. In Fig. 3a–c, vx of incident and reflected electrons across a constant energy slice are shown. vx has the opposite sign between incident electron and reflected electron and is highly asymmetric due to the broken left-right symmetry of the BLG band contour.

Group velocities of incident and reflected electrons.

(a)–(c) Group velocity vx; (d)–(f) group velocity vy; and (g)–(i) incident and reflection angles of an incident K valley electron at a given ky. The energies are εk = 0.5ε0, εk = 2ε0 and εk = 5ε0 respectively for column 1, 2 and 3. In (a)–(c), vx is positive for incident electrons and negative for reflected electrons. The RER regime is enclosed between the dashed lines in (d)–(i). In (d)–(f), sign reversal of vy corresponds to RER. In (g)–(i), the reflection angle of RER does not change sign since electron is reflected to the same side of the normal. At small εk, almost all of the permissible reflections are RER. As Ek increases, more permissible states becomes specular reflection states (which lies outside the RER windows) and the RER angle approaches 0°.

The group velocity component vy is the most important quantity in determining the electron reflection type (Fig. 3d–f). Sign reversal of vy at a fixed ky indicates RER (enclosed by dotted lines in the Fig. 3d–i). The incident electron vy reaches a sharp maximum when the band contour is flattened as ky increases. At  , vy no longer changes sign upon reflection and the reflection becomes specular. At small εk, almost all permissible reflection states are within the RER window and hence RER is dominant. The specular reflection states (outside the RER window) expands as εk increases, making RER relatively less profound. At εk = 5ε0 (Fig. 3f), more than half of the permissible ky corresponds to specular reflection.

, vy no longer changes sign upon reflection and the reflection becomes specular. At small εk, almost all permissible reflection states are within the RER window and hence RER is dominant. The specular reflection states (outside the RER window) expands as εk increases, making RER relatively less profound. At εk = 5ε0 (Fig. 3f), more than half of the permissible ky corresponds to specular reflection.

The non-uniqueness of θ is obvious in Fig. 3g–i, i.e. multiple sets of vx and vy produce the same θ. In contrast to vy, RER requires the sign of θ to remain unchanged upon reflection since in an retro reflection the electron is reflected to the same side of the normal of incidence. Due to the asymmetric constant energy band contour in k-space, the retro-reflected electrons do not trace back the incident path. Instead, they are mostly retro-reflected with smaller angle, maximally about 20°. The reflection angle approaches zero with increasing εk as the constant energy band contour becomes ‘smoother’ and loses the anisotropic band contour required to effectively produce large-angle RER. At εk > 10.9ε0, the reflection θ drops below zero, i.e. reflected electrons are placed on the opposite side of the incident normal and therefore all electron reflection becomes specular-type.

Absence of Andreev reflection at BLG/S

A highly electron-reflective interface is preferred for the observation of RER. Such an interface conveniently occurs in a ballistic BLG/S junction (Fig. 4) where electron transmission across the junction is completely suppressed due to the spinor structure of the BLG electron wavefunction. The superconductor is assumed to be s-wave type with isotropic pairing potential Δ* = Δ and is induced intrinsically in BLG via the proximity effect12 (thus avoiding lattice mismatch problems). The quantum transport across the junction can be described by Bogoliubov-de Genne (BdG) equations in the form of HΨ(r) = εΨ(r), where H is the Hamiltonian describing the excitation in BLG/S junction. The reflection coefficients can then be obtained by solving the BdG equation and matching the wavefunctions at the boundary13 (see Supplementary Information). The reflection probabilities were found to be Rh = 0 and Re = 1 for AR and electron→electron reflection respectively. Electron→electron reflection is therefore the only permissible process in the low energy regime of BLG/S and such a junction acts as a 100% reflective electron-mirror.

RER in BLG/S junction.

Green, blue and gray arrows indicate incident electron, retro-reflected electron and transmitted quasiparticle respectively. Transmission across the junction is forbidden due to the 2π Berry phase nature of bilayer graphene electron. The junction is hence 100% electron-reflective.

BLG/S junction as a valley-selective Veselago electron-mirror

The nature of RER in BLG/S is related to Veselago optics14. A Veselago electron-lens based on single layer graphene (SLG) and BLG p-n junctions has previously been reported15,16. Such junctions are Veselago electron-lenses because of the negative electron refractive index. In SLG, the negative electron refractive index originates from the existence of a lower Dirac sub-band which has opposite quasiparticle dynamics in comparison with the upper Dirac sub-band15. In BLG, the negative electron refractive index originates from its anisotropic constant energy band contour16. In contrast to a Veselago electron-lens, BLG/S is equivalent to a Veselago electron-mirror.

In optics, ray refraction is governed by Snell's Law

where ni and nt are the refractive index at the incident side and at the transmitted side respectively. A negative sign is added to the right hand side of Eq. (2) since we define the reflection angle θr to have the same sign as the incident angle θi if the reflected ray is on the same side of the normal of incidence as the incident ray. For simplicity, we consider a Veselago lens with nt = −ni. Since θi = θr the transmitted ray is placed at the ‘wrong’ side of the normal of incidence and this results in the transmitted ray, originating from a point source, being re-focused after propagating a certain distance in the transmission side of the interface (Fig. 5a). The Veselago lens is therefore a flat lens with ray-focusing behavior. For the reflection problem, a reflection ‘Snell's Law’ can also be written as ni sin θi = −nr sin θr where nr is the refractive index on the reflected side. The reflection ‘Snell's Law’ is however redundant in the usual case, since reflection occurs in the same medium where nr = ni and hence θr = −θi. To construct a Veselago mirror, we consider a hypothetical anisotropic medium with nr = −ni, i.e. the refractive index of the medium undergoes a sign change when a ray travels in the opposite direction with respect to the incident ray. This leads to the retro-reflection condition of θr = θi. The reflection interface is Veselago-like since the reflected ray is placed at the ‘wrong’ side of the incident normal. The retro-reflected rays, emitted from a point source, trace back their original incident path and are re-focused at the incident side of the interface (Fig. 5b). The interface can therefore be regarded as a flat Veselago mirror with ray-focusing behavior. It becomes obvious that the RER effect in BLG/S is equivalent to a Veselago electron-mirror. In BLG/S, the absence of AR makes the interface a perfect electron-mirror and the RER process is Veselago-like. BLG/S is therefore a flat Veselago electron-mirror with electron focusing ability.

Schematic drawings of (a) Veselago lens with nt = −ni; and (b) Veselago mirror nr ≈ −ni.

In the Veselago lens, a ray emitted from a point source (denoted by yellow triangle) is focused at the transmitted side of the interface. For the Veselago mirror, nr ≈ −ni is chosen for better visual clarity. The retro-reflected ray is focused at the incident side of the interface.

In BLG, the low energy electrons reside in two inequivalent K and K′ valleys. Intervalley scattering is strongly suppressed17. Devices utilizing this robust valley degree of freedom in graphene, valleytronics, have been proposed18. The first step towards valleytronics is a valley polarizer. The RER phenomena of BLG/S junction offers another simple way to separate electrons from different valleys without the need of cutting18, straining19, terahertz laser-irradiating20 or selective-damaging21 graphene. The K and K′ electron excitation spectrum of BLG/S has an opposite constant energy band contour (Fig. 6a and Fig. 6b). The reflection states in the K valley have a much ‘smoother’ constant energy band contour (Fig. 6a) than the reflection states in the K′ valley (Fig. 6b). This immediately suggest that the electron reflection in BLG/S is valley-selective. In Fig. 6c, it can be seen that the K electrons are predominantly retro-reflected with small angle θ < 20° while the K′ electrons are predominantly retro-reflected with large angle 50° < θ < 70°. SER occurs only at the upper and lower tips of the constant energy band contour when |ky| is large. It should be emphasized that valley-selective reflection is only possible when electrons undergo retro-reflection. The specularly reflected electrons are always divergently reflected and the valley states are mixed since the upper and lower ‘tips’ of the constant energy band contour at large |ky| are approximately identical for both K and K′ valleys. In Fig. 6d, the RER trajectory of electrons injected from a point source is shown. The BLG/S junction acts as a valley-selective dual focusing electron mirror with K electrons being focused further away from the junction due to the ’smoother’ constant energy band contour of K reflection states while K′ electrons are focused closer to the junction due to the ‘sharper’ constant energy band contour of K′ reflection states.

The electron excitation spectrum of BLG/S at (a) a K valley and (b) a K′ valley with εF = 0.5ε0 and Ek = ε0.

The RER constant energy band contour of the K valley (red dashed curve) is significantly ‘smoother’ than that of the K′ valley (green dashed curve). At large |ky| (SER regime), K and K′ band contours become approximately identical; (c) Reflection angles of K (red curve) and K′(green curve) electrons. K electrons are predominantly focused via smaller angle (< 20°) than that of the K′ electrons (≈80°). (d) RER trajectory of electrons emitted from a point source situated at P (denoted by yellow triangle). Blue rays represent the incident electrons. The interface acts as a valley-selective dual-focus electron mirror with K electrons (red rays) being focused further away from the interface than the K′ electrons (green rays).

Discussion

In Fig. 2, we show that the anisotropic constant energy band contour of BLG allows RER to occur. The reversal of vy group velocities upon reflection, as shown in Fig. 3, further illuminates the peculiar RER phenomena in BLG. It should be emphasized that the RER is more profound in the low energy regime of εk ≈ ε0. This requires high quality samples with carrier concentrations n ≈ 1011 cm−2 6 which is experimentally achievable22. RER does not survive in energy regimes higher than εk > 10.9ε0 since the reversal of vy upon reflection can no longer occur as the anisotropy of the constant energy band contour is lost.

The absence of AR in a BLG/S junction at low energy regimes is in agreement with previous study on BLG/S junction utilizing a four-band model without low energy band anisotropy23. It was shown that AR in BLG is a small effect in the order of Ek/γ1. Here we further demonstrate that AR is not only a small effect but is completely absent in the low energy regime. The absence of AR is related to the Klein tunneling effect and Berry phase in BLG. In BLG with isotropic and parabolic energy dispersion, electrons incident normal to a potential barrier are backscattered with unit-probability since the transmission mode normal to the interface is evanescent as encoded in the 2π Berry phase of its spinor wavefunction24,25. The 2π Berry phase is also retained when the low energy anisotropy is included26. Due to the large Fermi mismatch at the junction ( ), the transmission modes are always perpendicular to the interface for any incident angles and hence instead of perfect electron backscattering at only normal incidence, electrons reflect with unit probability at any incident angles in a BLG/S junction. Mathematically, this can be explained by the unique spinor-form of the BLG low energy electron wavefunctions. The transmitted spinor-wavefunction in the superconductor side for electron-like and hole-like excitations are, respectively,

), the transmission modes are always perpendicular to the interface for any incident angles and hence instead of perfect electron backscattering at only normal incidence, electrons reflect with unit probability at any incident angles in a BLG/S junction. Mathematically, this can be explained by the unique spinor-form of the BLG low energy electron wavefunctions. The transmitted spinor-wavefunction in the superconductor side for electron-like and hole-like excitations are, respectively,

where u and v are the BCS coherence factors,  ,

,  corresponds to the wavefunction amplitude at sub-lattice A ↑ and B ↓ respectively. The superscript (i, r) denotes incidence and reflection states respectively. Upon transmission, the normal-transmitted spinor follows the equality

corresponds to the wavefunction amplitude at sub-lattice A ↑ and B ↓ respectively. The superscript (i, r) denotes incidence and reflection states respectively. Upon transmission, the normal-transmitted spinor follows the equality  . This essentially uncouples the electron-reflection coefficient from the other transmission/hole-reflection coefficients, resulting in our angular-independent result: Re = 1 (see Supplementary Information). This aspect is in stark contrast to the single layer graphene/superconductor junction (SLG/S) where electrons reflect in an entirely opposite way: AR occurs with unit-probability only at normal incidence4. The perfect normal-transmission of electrons in graphene is a signature of the π Berry phase of the massless Dirac fermions24,27. The superconducting wavefunction in SLG/S is in the form of

. This essentially uncouples the electron-reflection coefficient from the other transmission/hole-reflection coefficients, resulting in our angular-independent result: Re = 1 (see Supplementary Information). This aspect is in stark contrast to the single layer graphene/superconductor junction (SLG/S) where electrons reflect in an entirely opposite way: AR occurs with unit-probability only at normal incidence4. The perfect normal-transmission of electrons in graphene is a signature of the π Berry phase of the massless Dirac fermions24,27. The superconducting wavefunction in SLG/S is in the form of  ,

,  where subscripts A and B correspond to the wavefunction amplitudes at the two inequivalent sub-lattices A and B respectively. Upon transmission, the spinor follows a rather different relation of

where subscripts A and B correspond to the wavefunction amplitudes at the two inequivalent sub-lattices A and B respectively. Upon transmission, the spinor follows a rather different relation of  . The hole and electron reflection coefficients are mathematically entangled with each others in this case and hence the AR reflection coefficient is angularly dependent on the electron incident angle.

. The hole and electron reflection coefficients are mathematically entangled with each others in this case and hence the AR reflection coefficient is angularly dependent on the electron incident angle.

In conclusion, graphene has again surprised us by allowing the peculiar RER to occur in its bi-layered form. The occurrence of RER in BLG while avoiding the violation of the momentum conservation rule represents a conceptually simple yet astonishing example highlighting one major difference between classical mechanics and quantum mechanics. In a BLG/S hybrid junction, the 2π Berry phase of low energy electrons in BLG manifests itself in a striking manner: AR is completely absent regardless the angle of incidence. This makes BLG/S a rather ideal platform to demonstrate RER since the competing AR process is fully eliminated. The absence of AR in BLG/S junction can be experimentally verified as the absence of supercurrent flow in the low Fermi level regime. Finally, the valley-inequivalent RER phenomena in BLG/S is analogous to a valley-selective Veselago electron-mirror. The valley-selective dual-focusing behavior suggests a potential application in the field of valleytronics.

Method

See Supplementary Material for derivation of the reflection coefficients.

References

Goldstein, H., Poole, C. P. & Safko, J. L. Classical Mechanics (Addison Wesley, 2002).

Andreev, A. F. Thermal conductivity of the intermediate state of superconductors. Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 46, 1823 (1964).

de Gennes, P. G. Superconductivity of Metals and Alloys (Benjamin, 1966).

Beenakker, C. W. J. Specular Andreev reflection in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 067007 (2006).

Lv, B., Zhang, C. & Ma, Z. Specular Andreev reflection in the interface of a two-dimensional semiconductor with Rashba spin-orbit coupling and a d-Wave superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 077002 (2012).

McCann, E. & Fal'ko, V. I. Landau-Level degeneracy and quantum Hall effect in a graphite bilayer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 086805 (2006).

Zutic, I. & Das Sarma, S. Spin-polarized transport and Andreev reflection in semiconductor/superconductor hybrid structures. Phys. Rev. B 60, R16322 (1999).

De Jong, M. J. M. & Beenakker, C. W. J. Andreev reflection in ferromagnet-superconductor junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 1657 (1995).

Yokoyama, T., Tanaka, Y. & Inoue, J. Charge transport in two-dimensional electron gas/insulator/superconductor junctions with Rashba spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. B 74, 035318 (2006).

Dimoulas, A. Barrier-induced enhancement of Andreev reflection for minority-spin quasiparticles in ferromagnetic metal/insulator/superconductor ballistic junctions. Phys. Rev. B 61, 9729 (2000).

Tanaka, Y. & Kashiwaya, S. Theory of tunneling spectroscopy of d-Wave superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 3451 (1995).

Heersche, H. B., Jarillo-Herrero, P., Oostinga, J. B., Vandersypen, L. M. K. & Morpurgo, A. F. Bipolar supercurrent in graphene. Nature 446, 56–59 (2012).

Blonder, G. E., Tinkham, M. & Klapwijk, T. M. Transition from metallic to tunneling regimes in superconducting microconstrictions: Excess current, charge imbalance and supercurrent conversion. Phys. Rev. B 25, 4515 (1982).

Veselago, V. G. The electrodynamics of substances with simultaneously negative values of ε and µ. Sov. Phys. Usp. 10, 509–514 (1968).

Cheianov, V. V., Fal'ko, V. & Altshuler, B. L. The focusing of electron flow and a Veselago lens in graphene p-n junctions. Science 315, 1252–1255 (2007).

Peterfalvi, C. G., Oroszlany, L., Lambert, C. J. & Cserti, J. Intraband focusing in bilayer graphene. New J. Phys. 14, 063028 (2012).

Morozov, S. V. et al. Strong suppression of weak localization in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 016801 (2006).

Rycerz, A., Tworzydlo, J. & Beenakker, C. W. J. Valley filter and valley valve in graphene. Nat. Phys. 3, 172–175 (2007).

Wu, Z., Zhai, F., Peeters, F. M., Xu, H. Q. & Chang, K. Valley-dependent Brewster angles and Goos-Hanchen effect in strained graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 176802 (2011).

Abergel, D. S. L. & Chakraborty, T. Generation of valley polarized current in bilayer graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 062107 (2009).

Gunlycke, D. & White, C. T. Graphene valley filter using a line defect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 136806 (2011).

Feldman, B. E., Martin, J. & Yacoby, A. Broken-symmetry states and divergent resistance in suspended bilayer graphene. Nature Phys. 5, 889–893 (2009).

Ludwig, T. Andreev reflection in bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 79, 195322 (2007).

Katsnelson, M. I., Novoselov, K. S. & Geim, A. K. Chiral tunneling and the Klein paradox in graphene. Nat. Phys. 2, 620–625 (2006).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Unconventional quantum Hall effect and Berry's phase of 2π in bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 2, 177–180 (2006).

Miktik, G. P. & Sharlai, Y. V. The Berry phase in graphene and graphite multilayers. Low Temp. Phys. 34, 794 (2008).

Ando, T., Nakanishi, T. & Saito, R. Berry's phase and absence of back scattering in carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 67, 8, 2857–2862 (1998).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Dr. David Martin (University of Wollongong) for fruitful discussion and his help in preparing this manuscript. The project is funded by Australian Research Council. ZSM acknowledges the financial support from the NBRP of China (2012CB921300) and NNSFC Grants (No. 91021017 and No. 11274013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S.A., Z.S.M. and C.Z. initiated the idea and performed the analysis. Y.S.A. performed simulation. All authors co-wrote and revised the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ang, Y., Ma, Z. & Zhang, C. Retro reflection of electrons at the interface of bilayer graphene and superconductor. Sci Rep 2, 1013 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01013

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01013

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.