Abstract

We investigate a dc electric concentrator for steady current fields theoretically and experimentally. Based on the transformation electrostatics, we show that the dc concentrator can focus electric currents into the central concentrated region and enhance the electric field and current density. Outside the concentrator, the current lines are distributed as the same as those in a homogeneous conducting material. Hence, such a dc electric concentrator has no impact on other external devices. Using the analogy between electrically conducting materials and resistor networks, we design, fabricate and test a dc concentrator using the circuit theory. The measured results agree very well with the theoretical predictions and numerical simulations, demonstrating the perfect concentrating performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the past a few years, transformation optics (TO) devices have caused much attention1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20, such as electromagnetic (EM) invisibility cloaks. Most TO devices were considered and designed in the time-varying EM fields1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 and a few devices have also been dealt with for static fields11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. In fact, the static fields play a significant role in several applications, e.g. they are involved in photocopy machines, electrostatic spraying systems and the electric impedance tomography. They can also be used to detect landmines and torpedoes.

Early in 2003, Greenleaf et al. studied the coordinate transformation in static potential11, in which they constructed anisotropic conductivities that give rise to the same voltage and current measurements on the boundary as those of a homogeneous and isotropic conductivity. Then in 2007, Wood and Pendry proposed a dc metamaterial design, which is based on super-conducting materials and the cloaking for static magnetic field was suggested12. Later, dc metamaterials have been further investigated theoretically and verified experimentally by different groups13,14,15,16,17,18,19. The EM concentrators for time-varying fields were first proposed by Rahm et al.9 and developed in10. However, the EM concentrators have never been demonstrated experimentally since they demand highly anisotropic material parameters with extreme values, which cannot be realized using the current technologies.

Results

In this paper, we theoretically and experimentally investigate the concentrating device for the steady current fields and realize a dc electric concentrator. Using the transformation electrostatic theory and exploiting the connection between conductivities in conducting materials and resistors in the circuit theory, we fabricate such the dc concentrator using the resistor network. The proposed dc concentrator could be useful in concentrating or enhancing current densities and other static-field manipulations.

The principle of dc concentrator is shown in Fig. 1, in which Panel a illustrates a bundle of electric currents flowing in a homogeneous and isotropic conducting material, while Panel b demonstrates the current flows when we put a dc electric concentrator inside the material, which can smoothly guide the electric currents into the central region, but does not make perturbations outside. As has been proved, the Laplace Equation maintains the form invariance under the coordinate transformation and hence the TO theory applies well to dc fields11,20. Using the TO theory, the dc concentrator can be easily designed by concentrating a sphere into the center of the sphere while diluting a spherical shell into the remaining region. For the two-dimensional (2D) case, we adopt a linear transformation between the physical and virtual spaces:

in which, k1 = b/a, k2 = (c−a)/(c−b) and k3 = (b−a)/(c−b) are constant coefficients under the cylindrical coordinate system. The electric concentrator contains three regions. In the central circular core with radius ρ'≤ a, the current density is enhanced by k1 times; in the middle layer (a ≤ ρ’≤ b), the current density is concentrated into the central core; in the outer layer (b≤ ρ’≤ c), the current density is “diluted” by k2 times. Then the transformed conductivity for the electric concentrator is then derived using the transformation electrostatics as

in which the primed variables belong to the physical space, the unprimed ones belong to the virtual space and  . It is interesting to notice that, implied in equation (2), the central “concentrated” region is isotropic and the conductivity is the same as that of the background material for 2D case. In the “diluted” region, the conductivity is anisotropic, whose ρ component is a monotonously decreasing function on radius, while the ϕ component is a constant.

. It is interesting to notice that, implied in equation (2), the central “concentrated” region is isotropic and the conductivity is the same as that of the background material for 2D case. In the “diluted” region, the conductivity is anisotropic, whose ρ component is a monotonously decreasing function on radius, while the ϕ component is a constant.

The principle of a dc concentrator.

(a) The current density vectors in the isotropic and homogeneous material illuminated by a planar source. (b) The current density vectors when a concentrator exists in the homogeneous background illuminated by the planar source, from which it is noticed that the currents are concentrated to the central region and enhanced. Here, the blue curves denote the current density vectors.

We, firstly, take an example to illustrate the focusing effect of the dc electric concentrator based on numerical simulations, in which we choose a = 1 cm, b = 10 cm, c = 11 cm and background material is homogeneous with conductivity σ0 = 1 S/m. In a homogeneous material, the potential is governed by the Laplace equation in the absence of source

At the position of x = −0.25 m, there is a planar metallic plate with the potential of U0 = 5V and the metallic plate at x = 0.25 m is connected to the ground. If the potential is invariant in the y and z directions, then it will vary linearly in the x direction as U = −10x+2.5, as shown in Fig. 2a. Figure 2c illustrates the electric potential distributions inside and outside the electric concentrator. We can see that, outside the concentrator, the electric potential distribution is the same as that in the homogeneous material. Compared with the virtual region shown in Fig. 2b, the electric potential distribution inside the concentrated region (U’ = −100x+2.5) is “focused” but not enhanced, as shown in Fig. 2d. In the other word, the electric potential in the region ρ≤b in Fig. 2b is concentrated into the central region ρ’≤ c, as illustrated in Fig. 2d. In the diluted region a≤ ρ’≤ c displayed in Fig. 2c, the electric potential can be transformed from the region b≤ ρ≤ c by the mapping expressed in Eq. (1).

Fig. 3a demonstrates the electric field intensity |E| inside and outside the concentrator. From the Maxwell's equation, we know that

In the homogeneous material, Ex = 10 V/m, which is the same as that in the region outside concentrator. In the concentrated region, predicted by the transformation electrostatic theory, the electric field will be enhanced by k1 = b/a = 10 times, i.e., 100 V/m. This has been verified by the numerical simulations, as shown in Fig. 3a. In the “diluted” region, the minimum electric field has been reduced by k2 = (c−a)/(c−b) = 10 times, i.e., 1 V/m. Fig. 3b illustrates the total current densities inside and outside the concentrator, which are given by

We observe from Fig. 3b that, outside the concentrator, the current densities are the same as those in the homogeneous materials. As predicted, in the central concentrated region, the current densities are enhanced by k1 = 10 times. In the “diluted” region, due to the anisotropic properties of the conductivity, the distribution of current densities is different from that of the electric field. From Eq. (2), we know that the conductivity tensor  in the “diluted” region is orthometric and the determinant equals 1, so it is a rotational matrix. Combining with Eq. (5), we can obtain the current density by rotating the distribution of electric fields, as shown in Fig. 3b. It is apparent that the current density is strongly enhanced in the concentrated region.

in the “diluted” region is orthometric and the determinant equals 1, so it is a rotational matrix. Combining with Eq. (5), we can obtain the current density by rotating the distribution of electric fields, as shown in Fig. 3b. It is apparent that the current density is strongly enhanced in the concentrated region.

Eq. (2) shows that the realization of dc concentrator requires anisotropic and inhomogeneous conductivities. Fig. 4a demonstrates the required radial and tangential components of the conductivity tensor for the dc concentrator with inner and outer radii of 5 cm and 15 cm, respectively. Clearly, the required conductivities are difficult to be realized in nature, but they can be easily emulated using the circuit theory. Suppose that a continuous conducting material plate with the conductivity σ and thickness h, which may extend to infinity in the radial direction. The material may be inhomogeneous and anisotropic. To make an equivalence of the material to a resistor network, the continuous material is discretized using the polar grids. According to Ohm's law, each elementary cell in the grid can be implemented by two resistors

where Δρ and Δϕ are step lengths in the radial and tangential directions, respectively. Thus the anisotropic conductivity tensor can be implemented easily using different resistors in different directions. To make simulations and measurements, the infinitely-large material should be tailored to have a suitable size. Like the perfect matching layers in the time-varying problems, matching resistors are added in the outer ring to emulate an infinite material. Using the theorem of uniqueness, the matching resistors can be easily obtained as19

in which r0 is the distance between the ground and the source point and the definitions of other geometrical parameters are presented in Fig. 4c. Hence the required resistors for the dc concentrator are illustrated in Fig. 4b. It is clearly shown that all resistors have moderate values and can be commercially obtained.

To verify the correctness and effectiveness of the design, we first simulate the homogeneous background material based on the resistor network. The simulation results of potential distributions under the excitation of a point source are shown in Fig. 5a. As predicted from electrostatic theory, the equipotential lines are concentric circles. Figs. 5b and 5c demonstrate the simulation and measurement results of a dc concentrator with a = 5 cm, b = 10 cm and c = 15 cm based on the resistor network. The fabricated dc concentrator is illustrated in Fig. 6 and will be discussed in details in Methods. In experiments, the potential is much easier to measure than the current density and hence we simulate and measure potential distributions. All simulations are performed using the commercial software, the Agilent Advanced Design System (ADS). The simulated potential distributions of the dc concentrator are shown in Fig. 5b. We clearly observe that the potential distributions outside the concentrator keep the original equipotential lines as those in the homogeneous material, which indicates that the concentrator has no effect on any external devices. The measurement results of the dc concentrator are presented in Fig. 5c, demonstrating excellent concentrating performance. To verify such a design for a dc concentrator with large “concentrated” factor, we fabricated another device. Figs. 5d and 5e demonstrate simulation and measurement results of a dc concentrator with a = 1 cm, b = 10 cm and c = 11 cm. We ploted the potential distributions in the simulation and experiment along a line y = 0 cm in Fig. 5f. We observed that the tested result is agreed very well with the simulation one.

The ADS simulation and measurement results of potential distributions without and with the dc concentrator.

(a) The simulation result in a homogeneous and isotropic material. (b) The simulation result when the central region is concentrated with a = 5 cm, b = 10 cm and c = 15 cm. (c) The measurement result when the central region is concentrated with a = 5 cm, b = 10 cm and c = 15 cm. (d) The simulation result when the central region is concentrated with a = 1 cm, b = 10 cm and c = 11 cm. (e) The measurement result when the central region is concentrated with a = 1 cm, b = 10 cm and c = 11 cm. (f) The simulated and measured potential distributions along a line y = 0. The measured potential has very good agreement to the simulation. Hence, nearly perfect concentrating effect is observed.

Discussion

A careful comparison between Figs. 5b and 5c shows excellent agreements between the experiments and simulations, both inside and outside the concentrator. Although the current densities in the resistors cannot be measured directly, we can compare the current densities in the central region of the dc concentrator and in the homogeneous material because the resistors are constants in such two cases. Hence, we can calculate the current density enhancement factor from the voltage difference between the corresponding resistors. In the excitation of point source, the potential distribution in the isotropic and homogeneous circular material can be described as

where A1 and A2 are coefficients determined by the positions of the source and ground. In the ADS simulations and experiments, we observe that the current density in the concentrated region has been enhanced by 1.7 times for the case of a = 5 cm, b = 10 cm and c = 15 cm and by 5.6 times for the case of a = 1 cm, b = 10 cm and c = 11 cm, compared to the same region in the homogeneous material due to potential distribution in the logarithmic law. We remark that the enhancement factors are a little bit smaller than the theoretical calculations due to the errors of practical resistors. Therefore, in the dc concentrator, the electric potential is concentrated, while the electric field and current density are enhanced.

In conclusion, we have proposed and made the first experimental verification of the dc electric concentrator in the steady current fields. Such a transformation optics device can concentrate the current into a designed central region and enhance the current density inside. With the help of modern integrated circuit technologies, it is possible to extend such a device to the nano scale. Hence the proposed device has potential applications in the electric impedance tomography technology, graphene and other integrated circuits.

Methods

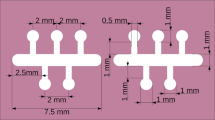

In the experimental setup of the first concentrator sample, the background material has the conductivity of 1 S/m, which is cut into a circular region with radius 25 cm. In our design, the geometrical parameters are chosen as a = 5 cm and c = 15 cm. To layout the 4-mm-long patch resistors along the tangential direction appropriately in the sample, we put on a circular metallic plate with radius 5 cm in the central region, which is equivalent to a conducting point with infinitesimal radius due to its perfect-conductivity nature in the steady currents. Hence, in the actual operation to construct the resistor circuit, the space between two adjacent layers is 0.8 cm instead of the theoretical interval of 1 cm, as shown in Fig. 5. However, thoughout the paper, we design the dc concentrators and plot the results according to the geometry size shown in Eq. (6) and (7). We adjust the spacing between adjacent resistors in the radial redirections to layout the inner-layer resistors in the actual circuits. Following the above-mentioned design procedure, the background material together with the dc concentrator is divided into 25×36 cells using the polar grids. The resistor network contains 25 concentric layers in the radial direction and 36 nodes in the tangential direction, which is built on a printed circuit board (PCB) with thickness of 2 mm. The concentrated region of the dc concentrator occupies an area of 5 layers, the diluted region employs another 10 layers and the remaining 10 layers are background material. The fabricated sample is shown in Fig. 5.

For the second sample, the central concentrated region has one-layer resistors with radius a = 1 cm and the diluted region has 10 layers of resistors, respectively. The remaining 9 layers are background material. In both samples, all resistors are commercially available chip-fixed resistors with a high accuracy of 0.1%. An Agilent voltage source with 5V magnitude is connected to the circuit network at the 24th layer. The voltage at each node is measured by using a 4.5-digit multimeter.

References

Pendry, J. B., Schurig, D. & Smith, D. R. Controlling electromagnetic fields. Science 312, 1780–1782 (2006).

Leonhardt, U. Optical conformal mapping. Science 312, 1777–1780 (2006).

Schurig, D. et al. Metamaterial electromagnetic cloak at microwave frequencies. Science 314, 977–980 (2006).

Greenleaf, A., Kurylev, Y., Lassas, M. & Uhlmann, G. Electromagnetic wormholes and virtual magnetic monopoles from metamaterials. Physical Review Letters 99, 183901 (2007).

Chen, H. S., Wu, B. I., Zhang, B. & Kong, J. A. Electromagnetic wave interactions with a metamaterial cloak. Physical Review Letters 99, 063903 (2007).

Jiang, W. X. et al. Design of arbitrarily shaped concentrators based on conformally optical transformation of nonuniform rational B-spline surfaces. Applied Physics Letters 92, 264101 (2008).

Rahm, M., Cummer, S. A., Schurig, D., Pendry, J. B. & Smith, D. R. Optical design of reflectionless complex media by finite embedded coordinate transformations. Physical Review Letters 100, 063903 (2008).

Chen, H. Y. & Chan, C. T. Transformation media that rotate electromagnetic fields. Applied Physics Letters 90, 241105 (2007).

Rahm, M. et al. Design of electromagnetic cloaks and concentrators using form-invariant coordinate transformations of Maxwell's equations. Photonics and Nanostructures-Fundamentals and Applications 6, 87–95 (2008).

Jiang, W. X., Cui, T. J., Yang, X. M., Ma, H. F. & Cheng, Q. Shrinking an arbitrary object as one desires using metamaterials. Applied Physics Letters 98, 204101 (2011).

Greenleaf, A., Lassas, M. & Uhlmann, G. Anisotropic conductivities that cannot be detected by EIT. Physiological Measurement 24, 413–419 (2003).

Wood, B. & Pendry, J. B. Metamaterials at zero frequency. Journal of Physics-Condensed Matter 19, 076208 (2007).

Magnus, F. et al. A d.c. magnetic metamaterial. Nature Materials 7, 295–297 (2008).

Navau, C., Chen, D. X., Sanchez, A. & Del-Valle, N. Magnetic properties of a dc metamaterial consisting of parallel square superconducting thin plates. Applied Physics Letters 94, 242501 (2009).

Sanchez, A., Navau, C., Prat-Camps, J. & Chen, D. X. Antimagnets: controlling magnetic fields with superconductor-metamaterial hybrids. New Journal of Physics 13, 093034 (2011).

Gomory, F. et al. Experimental Realization of a Magnetic Cloak. Science 335, 1466–1468 (2012).

Narayana, S. & Sato, Y. DC Magnetic Cloak. Advanced Materials 24, 71–74 (2012).

Chen, T. Y., Weng, C. N. & Chen, J. S. Cloak for curvilinearly anisotropic media in conduction. Applied Physics Letters 93, 114103 (2008).

Yang, F., Mei, Z. L., Jin, T. Y. & Cui, T. J. dc Electric Invisibility Cloak. Physical Review Letters 109, 053902 (2012).

Leonhardt, U. & Philbin, T. G. General relativity in electrical engineering. New Journal of Physics 8, 247 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part from the National Science Foundation of China under Grant Nos. 60990320, 60990321, 60990324, 61171024, 61171026, 60901011 and 60921063, in part from the National High Tech (863) Projects under Grant Nos. 2011AA010202 and 2012AA030702, in part from the 111 Project under Grant No. 111-2-05, in part from the Talent Project of Southeast University and in part by the Joint Research Center on Terahertz Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.X.J. and T.J.C. proposed and designed the theory of dc concentrators and performed initial verification, W.X.J. and C.Y.L. conceived the experiments and fabricated the devices. H.F.M. and Z.L.M. performed numerical simulations. T.J.C. supervised the design and experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, W., Luo, C., Ma, H. et al. Enhancement of Current Density by dc Electric Concentrator. Sci Rep 2, 956 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00956

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00956

This article is cited by

-

Bi-objective topology optimization for direct current concentration and heat flux cloaking using adaptive weighting method

Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization (2022)

-

Equivalence between positive and negative refractive index materials in electrostatic cloaks

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Experimental demonstration of an arbitrary shape dc electric concentrator

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Self-healing of damage inside metals triggered by electropulsing stimuli

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Transmitting information of an object behind the obstacle to infinity

Scientific Reports (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.