Abstract

To further optimize the culturing of preimplantation embryos, we undertook metabolomic analysis of relevant culture media using capillary electrophoresis time-of-flight mass spectrometry (CE-TOFMS). We detected 28 metabolites: 23 embryo-excreted metabolites including 16 amino acids and 5 media-derived metabolites (e.g., octanoate, a medium-chain fatty acid (MCFA)). Due to the lack of information on MCFAs in mammalian preimplantation development, this study examined octanoate as a potential alternative energy source for preimplantation embryo cultures. No embryos survived in culture media lacking FAs, pyruvate and glucose, but supplementation of octanoate rescued the embryonic development. Immunoblotting showed significant expression of acyl-CoA dehydrogenase and hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase, important enzymes for ß-oxidation of MCFAs, in preimplantation embryo. Furthermore, CE-TOFMS traced [1-13C8] octanoate added to the culture media into intermediate metabolites of the TCA cycle via ß-oxidation in mitochondria. These results are the first demonstration that octanoate could provide an efficient alternative energy source throughout preimplantation development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Improvements in culture media formulations have enhanced our ability to maintain healthy mammalian embryos in culture throughout the preimplantation stages. A recently developed sequential media for human embryos is based on the characteristic switch in energy source preference from pyruvate during the early cleavage stages to glucose during compaction and blastocoel formation1,2,3. The presence of certain amino acids in the culture media also improves preimplantation development of mammalian embryos4,5,6,7, such as glutamine and glycine being important for osmoregulation. Amino acids also provide precursors for protein and nucleotide synthesis and contribute to metabolic regulation and paracrine signaling in preimplantation embryos8,9,10. However, the precise combination of amino acids that should be added to the culture media for embryos is still unclear. Furthermore, very few published studies have analyzed the requirements for low-molecular-weight metabolites other than amino acids (e.g., fatty acids) in culture media for preimplantation embryos. On the other hand, recent reports emphasize the renewed focus in the field on in vitro environmental effects on preimplantation-embryo development (e.g., an increased incidence of both monozygotic twins and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome)11,12,13. Therefore, optimization of culture media for preimplantation embryos is an urgent issue. In this context, we sought to analyze the effects of low-molecular-weight metabolites in culture media on the growth of mouse preimplantation embryos, to better understand the metabolic demands of such embryos and inform both the further optimization of culture condition and efforts to identify a potential biomarker for embryo quality.

Omics technologies, including transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics, have been successfully applied to screen for biomarkers in biological fluids for cancers and autoimmune diseases14. Oligo DNA microarrays with RNA amplification was first employed as an omics technology to demonstrate the dynamics of global gene expression changes in mammalian preimplantation embryos15,16,17. However, transcriptomic analyses often fail to predict protein abundance or function. Advances in proteomic technologies including mass spectrometry (MS) have enabled groups of proteins within limited amounts of complex biological fluids and tissues to the identified18,19. Specifically, surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (SELDI-TOF) MS was used to generate protein profiles in culture media at all stages of mammalian embryonic development, demonstrating remarkable profile differences between early and expanded blastocysts and between developing blastocysts and degenerate embryos20,21. These studies also suggested that each preimplantation stage during the fertilized egg to blastocyst development has a distinctive secretome signature21.

Metabolomics profiling has the potential to simultaneously determine hundreds of small-molecule metabolites in cells and biological fluids such as culture media, serum and urine. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy22, gas chromatography–mass spectrometry23, liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS)24 and capillary electrophoresis–mass spectrometry (CE-MS)25 have been often used in metabolomic studies. Each of these technologies detects only a subset of all the metabolites present. Among them, CE-MS is a powerful tool to quantitatively determine small amounts of most ionic intermediate metabolites in the primary metabolic pathways (e.g., carbohydrates, amino acids, nucleotides and molecules involved in energy metabolism) and thus is a suitable profiling technique to study preimplantation embryos in the context of both hormone and metabolite analysis. Furthermore, CE-MS has successfully identified metabolite biomarkers for several diseases, including cancer and fulminant hepatitis25,26. Therefore, we applied CE-MS to the exploration of metabolic systems in preimplantation embryos in this study, focusing first on a candidate medium-chain fatty acid as an alternative energy source for preimplantation embryo culture.

Results

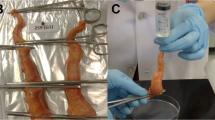

We analyzed 50-µl drops of either culture media from in vitro cultures of 100 mouse embryos during early and late preimplantation stages (the embryo group) or media just incubated without any embryos (the control group) (Fig. 1) and 28 metabolites were detected by CE-TOFMS.

Strategy for microdrop culture of synchronizing preimplantation embryos and the timing of culture media collection.

Embryos were collected from mated superovulated mice at 18 hours post-hCG and embryos with two pronuclei were discarded. Other embryos were incubated in KSOM and then those with 2PN were selected to synchronize in vitro embryo development (at 24 hours post-hCG). A hundred of zygotes were cultured in 50-µl drops of KSOM under oil at 37°C in an atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2. The embryos were then transferred into fresh KSOM at 55 hours post-hCG and further cultured until the blastocyst stage. Embryo-free control drops were incubated alongside the embryo-containing drops. Each of the spent media was analyzed by CE-TOFMS.

Embryo-derived metabolites

Twenty-three metabolites including 15 amino acids were significantly detected in the embryo group, but not in the negative control group (Fig. 2A). These are considered as embryo-derived metabolites generated via excretion from embryos. Comparison between the early- and late-stage embryos revealed that 17 metabolites were differentially excreted. Of these, 2 were excreted more at the early stages: glycine, an osmolarity regulator27 and hexanoate (Fig. 2A & Table 1). On the contrary, 15 metabolites (alanine, cis-aconitate, histidine, leucine, malate, methionine, phenylalanine, proline, putrescine, threonin, tryptophan, tyrosine, valine, 2-hydroxy-4-methylpentanoate and 2-hydroxypentanoate) were excreted in larger amounts in the later stages (Fig. 2A & Table 1).

CE-TOFMS analysis of metabolites in culture media during preimplantation development.

Twenty-eight metabolites were detected in the early-stage media (EM) and the late-stage media (LM). Both the embryo (+) experimental group and embryo (−) control group had 12 experimental replicates (n = 12), which used 100 embryos for the 50-µl-drop culture. Significance of differences of the metabolite concentrations was evaluated using Student's t-test, with P-values (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001). Values shown are mean values ± standard deviation (SD). (A) Released metabolites into culture media during preimplantation development. The concentrations of metabolites in the EMs were compared to that in the LMs. Twenty-three metabolites including 15 amino acids were significantly detected in the embryo (+) culture media, but not in the embryo (−) control media. These are considered as embryo-excreted metabolites (open box: early-stage culture media, shaded box: late-stage culture media). (B) Uptaken metabolites from culture media during preimplantation development. The concentration of metabolites in embryo (+) culture media was compared to that in embryo (−) control media. Five metabolites were significantly detected in both the embryo (+) and the embryo (−) culture media. These metabolites are considered as culture-media-derived: open box, embryo (−) early-stage media (the control group, EM); shaded box, embryo (+) early-stage media (the experimental group, EM); dark gray box, embryo (−) late-stage media (the control group, LM); black box, embryo (+) late-stage media (the experimental group, LM). N.D. means that the metabolite concentration was below the detection limit of the analysis.

Culture media-derived metabolites including octanoate, a medium-chain fatty acid

Five metabolites were significantly detected in both the negative control and embryo groups (Fig. 2B & Table 1). These are considered as culture media-derived metabolites, although only three of these metabolites (glutamine, lactate and pyruvate) are listed as media components in the manufacturer's information. Compared to the negative control group, the embryo group media showed significantly lower concentrations of pyruvate especially at the early stages, suggesting it as an important energy substitute at the cleavage stages. The two metabolites not found in the manufacturer's media formulation list were 5-oxoproline and octanoate. Octanoate is a medium-chain fatty acid that is thought to be carried into culture media by bovine serum albumin (BSA). Compared to the control group, the embryo group media showed significantly lower concentrations of octanoate throughout the preimplantation stages and based on this we hypothesized that preimplantation embryos consume octanoate as an alternative energy substitute.

BSA is commonly used as the macromolecular component in media for culturing mammalian embryos and several analyses of the fatty acid content of BSA28,29 have implicated BSA-binding fatty acids in both mouse and rat embryo development30. However, all these studies analyzed only long-chain fatty acids, with neither medium-chain nor short-chain fatty acids studied. In this study, we therefore focused on the kinetics of medium-chain fatty acids in embryonic development and metabolism.

Effect of octanoate on preimplantation development

To study the effect of octanoate on preimplantation development, embryos were cultured in vitro until the blastocyst stage in Potassium Simplex Optimized Medium (KSOM), fatty acid-deficient culture media, or octanoate-supplemented culture media and counted at 2.5, 4.5 and 5.5 days post-coitum (d.p.c.). Whereas only 42.0 ± 12.6% of the embryos cultured in fatty acid-deficient media reached the 8-cell or morula (8C/Mo) stage at 2.5 d.p.c., 65.6 ± 14.9% of embryos cultured in octanoate-supplemented media reached the 8C/Mo stage (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3A). Similarly, while 54.6 ± 10.3% of embryos cultured in fatty acid-deficient media had reached the blastocyst stage at 3.5 d.p.c., 76.9 ± 10.3% of embryos cultured in octanoate-supplemented culture media were classified as blastocysts at the same period post-coitum (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3B). In contrast, there was no significant difference in the hatching rate between embryos cultured in fatty acid-deficient and octanoate-supplemented culture media (35.6 ± 9.9% and 38.2 ± 5.2%, respectively) (Fig. 3C). These results revealed the important role of fatty acids in in vitro culture of preimplantation embryos and that octanoate alone could almost completely fulfill that role.

Effect of octanoate on preimplantation development in fatty acid-deficient culture media or in media lacking glucose, pyruvate and fatty acids.

The beneficial effect of octanoate supplementation on preimplantation development was clearly observed in both experimental conditions, using fatty acid-deficient and energy-depleted media. Embryos were cultured in (a) fatty acid-containing KSOM, (c) fatty acid-deficient media or (b) fatty acid-deficient and 100 µM octanoate-supplemented media (A–C). Alternatively, embryos were cultured in (e) media lacking glucose (Glu), pyruvate and fatty acids (energy-depleted media) or (d) energy-depleted and 100 µM octanoate-supplemented media (D–F). A vertical scale in each graph shows the developmental rate from 1-cell embryos to 8-cell embryos/morulae at 2.5 d.p.c. (A, C), from 8-cell embryos to blastocysts at 4.5 d.p.c. (B, E), or from hatched blastocysts at 5.5 d.p.c. (C, F). Results are shown as the mean % ± SEM, n > 4 experimental replicates, unpaired t-test performed within developmental stage; *P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.001). N.S. means not significant.

To further investigate the effect of octanoate on preimplantation development under energy-depleted conditions, embryos were cultured in vitro until the blastocyst stage in media lacking glucose, pyruvate and fatty acids (energy-depleted media) or the media supplemented with octanoate during preimplantation development. Few of the starting embryos (9.8 ± 2.9%) cultured in energy-depleted media reached the 8C/Mo stage, whereas 50.4 ± 2.9% of those embryos cultured with octanoate-supplemented media reached the 8C/Mo stage (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, only 8.3 ± 4.9% of starting embryos cultured in energy-depleted media reached the blastocyst stage, compared to 60.4 ± 7.4% incubated in octanoate-supplemented media (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3E). No embryos incubated in energy-depleted culture media showed blastocyst hatching, whereas octanoate supplementation allowed a successful rate of blastocyst hatching up to 21.3 ± 4.7% (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3F).

Expression changes in genes related to ß-oxidation during preimplantation development

Medium-chain fatty acids enter the mitochondrial matrix directly without any help from the carnitine transport system that is necessary for long-chain fatty acids and are first used as a substrate for medium-chain acyl-CoA synthetases (ACSM) in the matrix ß-oxidation system. Such activation of fatty acids by conversion into acyl-CoA thioesters allows their participation in catabolic pathways31. The ß-oxidation of fatty acids constitutes a repeated sequence of four reactions catalyzed by acyl-CoA dehydrogenases (ACADVL, ACADL, ACADM, ACADS), 2-enoyl-CoA hydratases (EHs), 3-hydroxy acyl-CoA dehydrogenases32 and 3-keto acyl-CoA thiolases (KATs), each of which comprise 2–4 distinct enzymes with different, but overlapping, chain-length substrate specificities (Fig. 4A). The substrate specificity for ACADVL, ACADL, ACADM and ACADS ranges from C20 to C12, from C20 to C8, from C12 to C4 and from C6 to C4, respectively33. Hydroxyacyl-CoA, a product of the fatty acid ß-oxidation cycle, is catalyzed by the mitochondrial trifunctional protein, which is a heterooctamer multienzyme complex consisting of four α-subunits (hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase alpha, HADHA) and the β-subunit (hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase beta, HADHB)34,35,36,37. Western blotting analysis using oocytes, 8-cell embryos and blastocysts showed significant expression of ACADM and HADHA throughout the preimplantation stages including the unfertilized egg stage, whereas ACADL was expressed only at the blastocyst stage, but not at the earlier stages (Fig. 4B). It therefore seems that all stages of preimplantation embryos are well equipped for mitochondrial ß-oxidation systems to metabolize octanoate.

The metabolic process of fatty acids and incorporation of label into the TCA cycle from [1-13C8] octanoate.

(A) Schematic diagram of fatty-acid metabolic process. Long-chain fatty acids are catalyzed by ACSL1, 3–6 (acy-CoA synthetase long-chain 1, 3–6) and CPT1 (carnitine O-palmitoyltransferase 1). Then, long-chain fatty acids are transferred from the cytosol to the mitochondria by CACT (carnitine acylcarnitine translocase) for subsequent β-oxidation. On the other hand, medium-chain fatty acids enter directly into the mitochondrial matrix and subsequently acyl-CoAs are synthesized. Acyl-CoA-fatty acid products are dehydrogenased by ACADM and ACADL and the products are subjected to the β-oxidation spiral. (B) Western blotting analysis of ACADM, ACADL and HADHA in oocytes, 8-cell embryos and blastocysts (U: unfertilized oocyte, 8: 8-cell embryo and B: blastocyst). Actin was used as a loading control. An amount of extracted protein corresponding to 100 oocytes or embryos was loaded per lane. The representative result is shown from three independent experiments. (C) Incorporation of 13C label into TCA-cycle metabolites in mitochondria from [1-13C8] octanoate-containing culture media. Box plot showing the amount of metabolites derived from octanoate (shaded boxes) and [1-13C8] octanoate (open boxes) cultures. Error bars represent SD. N.D. means that the metabolite concentration was below the detection limit of the analysis. P-value was calculated by Student's t-test (*P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.01).

Octanoate and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle

We hypothesized that octanoate supports preimplantation development by providing ATPs via ß-oxidation and the TCA cycle. To test this idea in the present study, we used stable isotope 13C-labeled octanoate as a tracer to follow the TCA cycle activity and establish whether octanoate is truly used as an energy substitute in preimplantation embryos. Embryos were incubated with octanoate (control group) or [1-13C8] octanoate (experimental group) from the 1-cell stage to the blastocyst stage. 13C was detected in intermediate metabolites of the TCA cycle and we compared the isotope ion peaks (M++1) –molecular ion peaks (1/M+) (M++1/M+) ratios between the groups. Interestingly, there were significant differences in M++1/M+ ratio between the groups in the metabolite levels of the initial part of the TCA cycle, including citrate, cis-aconitate, fumarate and malate, which were markedly higher in embryos incubated with [1-13C8] octanoate (Fig. 4C), while three TCA metabolites, iso-citrate, 2-oxoketoglucarate and succinyl CoA, were not detected. These findings indicated that octanoate was incorporated into the TCA cycle via ß-oxidation and thereby used as an alternative energy source in the mitochondria of preimplantation embryos.

Discussion

In this study we used CE-TOFMS to quantitatively determine small amount of ionic intermediate metabolites in embryo culture media including 16 amino acids, 2 amino-acid derivatives (putrescine and 5-Oxoproline) and other 10 molecules involved in primary energy pathways after in vitro culture of preimplantation embryos (Table 1). These 28 metabolites included 2 metabolites differentially excreted at the early stages of development (glycine and hexanoate) and 15 metabolites differentially excreted at the late stages (Fig. 2 and Table 1), indicating that late-stage preimplantation embryos excreted more metabolites into the culture media than early-stage embryos. This could reflect that embryonic metabolism is activated by a switch in energy source preference, from pyruvate during the early cleavage stages, to glucose during compaction and blastocele formation (Baltz & Tartia, 2009; Biggers & Summers, 2008; Lane & Gardner, 2007). The current study also showed that pyruvate was dramatically consumed in culture media at early stages rather than at late stages. Interestingly, Houghton et al. reported a sharp rise in metabolic activity at the morula stage, measured in terms of oxygen consumption in all species studied38.

Amino acids provide precursors for protein and nucleotide synthesis and contribute to osmoregulation, metabolic regulation and paracrine signaling in preimplantation embryos8,9,10. Glutamine is probably the amino acid most commonly added to embryo culture media. It is metabolized to glutamate and then to 2-Oxoketoglutarate, which is further oxidized through the TCA cycle to generate ATP39 and then excreted as alanine10. On the other hand, 16 amino acids were excreted from preimplantation embryos in this study (Fig. 2A). Of these, glycine is an important component of culture media for embryos due to its role in osmoregulation (Baltz & Tartia, 2009), while histidine, an amino acid excreted from porcine40 and human blastocyst41, is known to play a role in signaling to the uterine endometrium where it is decarboxylated into the signaling agent histamine by uterine histidine decarboxylase10. However, this latter putative role is hypothetical and might be species specific, since histidine production has not been detected in cattle embryos10. Methionine is also likely to play an important role in metabolic regulation and nucleotide synthesis, particularly in the methylation cycle involving folate and vitamin B12, which leads to subsequent DNA methylation. An amino acid profiling study of human embryos showed that developing embryos produced significantly more methionine than arresting embryos42.

In the present study, 10 molecules involved in primary energy pathways were detected in the media after in vitro culture of preimplantation embryos. Out of them, we focused on octanoate, a medium-chain fatty acid. Although the kinetics of medium-chain fatty acids in preimplantation embryos has never been reported, long-chain fatty acids are known to contribute to early embryonic development and the late stages of preimplantation mouse embryo development are known to involve fatty acid uptake and metabolism in short-term culture experiments43. However, long-chain fatty acids need a carnitine transport system to reach the mitochondrial matrix and generate ATP via ß-oxidation. Indeed, the inhibition of β-oxidation during zygote cleavage by etomoxir, an inhibitor of carnitine palmitoyltransferase Cpt1b, impaired subsequent blastocyst development in mice44. Mouse blastocysts incubated with methyl palmoxirate, another inhibitor of carnitine palmitoyltransferase, significantly reduces lactate production and cell numbers in the trophectoderm and inner cell mass45. Using radiolabeled palmitic acid added directly to the media, a highly significant increase in fatty acid oxidation was identified during the morula and blastocyst stages, with CO2 production rising to 200–500% of the levels observed in earlier stages43. All these findings clearly show an important role for long-chain fatty acids as an energy source at the late stages of preimplantation embryonic development. Furthermore, long-chain fatty-acid acyl-CoA dehydrogenases (ACADL)-deficient mice often show spontaneous death and gestational loss46 and ACADL-deficient preimplantation embryos show a lower survival ratio to the blastocyst stage than the wild-type controls47. The ACADL-null phenotype thus points to the overall importance of mitochondrial oxidation of long-chain fatty acids in embryonic development.

On the other hand, ACADM is responsible for catalyzing the dehydrogenation of medium-chain length (C4–C12) fatty acid thioesters33. ACADM-deficient mice show significant neonatal mortality, distinctive from ACADL-deficient mice, with approximately 60% of the ACADM-deficient pups dying prior to weaning at 3 weeks of age. It is likely that neonatal ACADM-deficient pups are manifesting sensitivity to fasting with decompensation in a short period of time if maternal milk is not ingested46. Although ACADM-deficient embryos may have little problem in vivo, they may show suppressed preimplantation development during in vitro culture, which may not provide such an ideal condition as in vivo and fail to provide adequate and balanced energy substitutes. We demonstrated herein that preimplantation embryos consumed octanoate throughout the preimplantation stages and traced [1-13C8] octanoate to intermediate metabolites of the TCA cycle via ß-oxidation in mitochondria. Furthermore, western blotting analysis indicated the protein expression of ACADM and HADHA throughout the preimplantation stages from oocyte to the blastocyst (Fig. 4B), whereas ACADL, which catalyzes long-chain fatty acids, was not expressed in oocytes or 8-cell embryos. These findings together suggested that medium-chain fatty acids are useful for all the stages of preimplantation embryos as an energy substitute for ß-oxidation in mitochondria.

Interestingly, Berger et al. investigated if preimplantation development of ACADL-deficient mice could be rescued in culture by supplying excess medium-chain, long-chain, or very-long-chain fatty acids. However, they failed to demonstrate any rescue by supplementing the culture media with fatty acids of a wide-range of chain-lengths47. This result is not consistent with our results. Their failure in the rescue of ACADL-deficient preimplantation embryos by octanoate may be caused by the unfavorable culture conditions used, which grows only 40–60% of wild-type embryos (as positive controls with fatty-acid-binding BSA) to the blastocyst stage. On the contrary, 97.6% of embryos (with fatty-acid-binding BSA) developed to the blastocyst stage in our study; 54.6% of embryos reached the blastocyst stage with all the fatty acids eliminated from culture; and supplementation of octanoate significantly recovered the developmental rate to the blastocyst stage up to 76.9%. This suggests that preimplantation embryos can consume octanoate as an alternative energy substitute.

In conclusion, all these results support our hypothesis that octanoate is an efficient alternative energy substitute throughout preimplantation embryo development, by directly entering the mitochondrial matrix without a chaperone transport system. Although follicular fluid, the physiological environment in which oocytes mature in vivo, contains both lipoproteins and free fatty acids48,49, current commercial defined media formulations used for oocyte and embryo culture do not intentionally include any fatty acid substrates50,51. Because the rate of human embryos reaching the blastocyst stage in vitro is not yet satisfactory compared to that of other animals such as mouse and bovine, in vitro culture conditions for human preimplantation embryos need further optimization. The epigenetic adverse effect on preimplantation-embryo development (e.g, an increase in monozyogotic twinning and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome) are the subject of recent studies and are likely to be attributed to the in vitro environment11,12,13. Therefore, optimization of culture media for preimplantation embryos is an urgent issue. Because fasting or shortness of the existing energy substitutes may occur to in-vitro-cultured embryos under such inadequately optimized condition of human preimplantation embryos without fatty acids, the inclusion of medium-chain fatty acids in culture media formulations may be effective for the optimization of chemically defined culture media and for improvements in the quality and safety of human preimplantation embryos.

Methods

Collection and manipulation of embryos and culture media

Six- to eight-week-old B6D2F1 mice were superovulated by injecting 5 IU of pregnant-mare serum gonadotropin (PMS; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) followed by 5 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG; Calbiochem) 48 h later according to a standard published method52. After hCG injection the females were placed with fertile males of the same strain and checked the following morning for copulation plugs.

Embryos were collected from mated superovulated mice at 18 hours post-hCG injection and embryos with two pronuclei were selected to synchronize the in vitro embryo development (at 24 hours post-hCG). The eggs were then thoroughly washed, selected for good morphology and collected. Fertilized eggs were cultured in synthetic oviductal media enriched with potassium (EmbryoMax KSOM Powdered Mouse Embryo Culture Medium; Millipore) at 37°C in an atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2.

-

1

Culture media analysis. Prior to being used for research, 100 zygotes were cultured in 50-µl drops of KSOM under oil. The embryos were then transferred into fresh culture media at 55 hours post-hCG and cultured until the blastocyst stage at 120 hours post-hCG (Fig. 1). Embryo-free control drops were incubated alongside the embryo-containing drops to allow for any non-specific amino acid degradation/appearance. Culture media were immediately frozen and stored at −80°C until metabolite extraction.

-

2

To study the function of octanoate during preimplantation development, embryos were cultured in KSOM, fatty acid-deficient culture media, octanoate-supplemented fatty acid-deficient culture media, energy-depleted culture media, or octanoate-supplemented energy-depleted culture media until 5.5 days postcoitum (d.p.c.). Embryonic morphology was assessed daily and the embryos were classified developmentally as follows: on 2.5 d.p.c., embryos at the 8-cell to morula stage, on 4.5 d.p.c., blastocyst stage and on 5.5 d.p.c., hatching blastocyst. The rate of development was assessed daily as the percentage of embryos meeting the development criteria from the starting number of embryos.

All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee of Keio University School of Medicine and the protocol was formally approved (Permit number #10240-1838).

13C Tracer Studies in preimplantation embryos

Collection of embryos cultured in octanoate- or [1-13C8] octanoate-supplemented and fatty acid-deficient culture media

Fertilized eggs were cultured in octanoate- or [1-13C8] octanoate (Iwai chemicals corporation, Tokyo, Japan)-supplemented fatty acid-deficient culture media at 37°C in an atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2. The embryos were cultured until the blastocyst stage at 120 hours post-hCG. Embryos were thoroughly washed and then immediately frozen and stored at –80°C until metabolite extraction.

Metabolite extraction of embryos for CE-TOFMS

To extract metabolites, preweighed deep-frozen samples from 100–300 embryos were left at room temperature to thaw. A 500-μl aliquot of methanol containing the internal standards [20 μmol/l each of methionine sulfone and D-camphor-10-sulfonic acid (CSA)] was added to the samples and then mixed with 200 μl Milli-Q water and 500 μl chloroform before centrifuging at 5,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. Subsequently, the aqueous layer was transferred to a 5-kDa cutoff centrifugal filter tube (Millipore, Billerica, MA) to remove large molecules. The filtrate was centrifugally concentrated and dissolved in 20 μl of Milli-Q water that contained reference compounds (200 μmol/l each of 3-aminopyrrolidine and trimesic acid) immediately before CE-TOFMS analysis.

Sample preparation of culture media for CE-TOFMS

For the extracellular metabolome analysis, the deep-frozen culture supernatants were thoroughly thawed and 8 μl aliquots were placed in a tube and mixed with 2 μl of an aqueous solution that contained 1 mmol/l each of methionine sulfone, CSA, 3-aminopyrrolidine and trimesic acid. The solution was centrifuged at 9,100 ×g for 5 min at 4°C and the supernatant was used for subsequent CE-TOFMS analysis.

Reagents for metabolomic analysis

All reagents used in this study were obtained from BACHEM AG (Bubendorf, Switzerland), MP Biomedicals (Aurora, OH), Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland), Toray Research Center (Tokyo, Japan), Wako Pure Chemicals Industries Ltd. (Osaka, Japan), or Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Stock solutions (1–100 mmol/l) were prepared in either Milli-Q water, 0.1 mol/l HCl, or 0.1 mol/l NaOH. All chemical standards were analytical or reagent grade. A mixed solution of the standards was prepared by diluting stock solutions with Milli-Q water immediately before CE-TOFMS analysis.

Analytical conditions for metabolomic analysis

Instrumentation for CE-TOFMS

All CE-TOFMS experiments were performed using an Agilent CE capillary electrophoresis system (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) equipped with an Agilent G3250AA LC/MSD TOF system (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA), an Agilent 1100 series isocratic HPLC pump, a G1603A Agilent CE-MS adapter kit and a G1607A Agilent CE-electrospray ionization53-MS sprayer kit. For system control and data acquisition, G2201AA Agilent ChemStation software was used for CE and Agilent TOF (Analyst QS) software was used for TOFMS.

CE-TOFMS conditions for cationic metabolite analyses

Cationic metabolites were separated in a fused-silica capillary (50 μm i.d. × 100 cm total length) filled with 1 mol/l formic acid as the reference electrolyte54. Sample solution was injected at 5 kPa for 3 seconds (approximately 3 nl) and a positive voltage of 30 kV was applied. The capillary and sample trays were maintained at 20°C and below 4°C, respectively. The sheath liquid that comprised methanol/water (50% v/v) containing 0.5 μmol/l reserpine was delivered at 10 µl/min. ESI-TOFMS was conducted in positive ion mode and the capillary voltage was set at 4,000 V. The flow rate of heated dry nitrogen gas (heater temperature, 300°C) was set at 10 psig. The fragmentor, skimmer and Oct RF voltages in TOFMS were set at 75, 50 and 125 V, respectively. An automatic recalibration function was performed using the following masses of two reference standards: [13C isotopic ion of the protonated methanol dimer (2MeOH+H)]+, m/z 66.06306; and [protonated reserpin (M+H)]+, m/z 609.28066. Mass spectra were acquired at a rate of 1.5 cycles per second from m/z 50 to 1,000.

CE-TOFMS conditions for anionic metabolite analysis

Anionic metabolites were separated in a commercially available COSMO(+) capillary (50 μm i.d. ×100 cm total length, Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan), which was chemically coated with a cationic polymer and filled with 50 mmol/l ammonium acetate solution (pH 8.5) as the reference electrolyte55,56. Sample solution was injected at 5 kPa for 30 s (approximately 30 nl) and a negative voltage of 30 kV was applied. Ammonium acetate (5 mmol/l) in 50% methanol/water mixture (v/v) containing 1 μmol/l reserpin was delivered as the sheath liquid at 10 μl/min. ESI-TOFMS was conducted in negative ion mode and the capillary voltage was set at 3,500 V. The fragmentor, skimmer and Oct RF voltages in TOFMS were set at 100, 50 and 200 V, respectively. An automatic recalibration function was performed using the following masses of two reference standards: [13C isotopic ion of the deprotonated acetic acid dimer (2CH3COOH-H)]−, m/z 120.03834; and [deprotonated reserpin (M-H)]−, m/z 607.26611. Mass spectra were acquired at a rate of 1.5 cycles per second from m/z 50 to 1,000. All other conditions were same as described above for cationic metabolite analysis.

CE-TOFMS data processing

The raw data were processed using our proprietary software (MasterHands)57,58. The overall data processing flow consisted of noise filtering, baseline correction, peak detection and integration of the peak areas from 0.02 m/z-wide sections of the electropherograms. Subsequently, the accurate m/z of each peak was calculated by Gaussian curve fitting in the m/z domain and the migration times were normalized to match the detected peaks among the multiple datasets. All target metabolites were identified by matching their m/z values and migration times59 with those of the authentic standard compounds. In this study, the tolerance was set to 40 ppm (m/z values) and 0.5 min (normalized migration time).

As for tracer analysis, target metabolites were derived from the fatty acid-deficient culture media supplemented with octanoate or [1-13C8] octanoate. Isotope ion peaks (M+)divided by molecular ion peaks (M++1) ratios (M++1/M+) were calculated only for metabolites of the TCA cycle-pathway. The M++1/M+ ratio of each metabolite was compared between groups.

Immunoblot analysis

Protein samples from embryos were solubilized in Sample Buffer Solution without 2-ME (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan), resolved by NuPAGE Novex on Tris-acetate mini gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to Immobilon-P transfer membrane (Millipore). The membrane was soaked in protein blocking solution (Blocking One solution, Nacalai) for 30 min at room temperature before an overnight incubation at 4°C with primary antibody, also diluted in blocking solution. The anti-ACADM antibody (Abcam), anti-ACADL antibody (Abcam), anti-HADHA antibody (Abcam) and anti-actin antibody (Abcam) were used at 1:50–300 dilution. The membrane was then washed three times with TBST (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20), incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (0.04 mg/ml) directed against the primary antibody for 60 min and washed three times with TBST. The signal was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate, Thermoscientific, Rockford, IL, USA) following the manufacturer's recommendations.

Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed by Student's t-test; differences with a P value < 0.05 were considered significant.

References

Baltz, J. M. & Tartia, A. P. Cell volume regulation in oocytes and early embryos: connecting physiology to successful culture media. Hum Reprod Update 16 (2), 166–176 (2010).

Biggers, J. D. & Summers, M. C. Choosing a culture medium: making informed choices. Fertil Steril 90 (3), 473–483 (2008).

Lane, M. & Gardner, D. K. Embryo culture medium: which is the best? Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 21 (1), 83–100 (2007).

Lane, M. & Gardner, D. K. Amino acids and vitamins prevent culture-induced metabolic perturbations and associated loss of viability of mouse blastocysts. Hum Reprod 13 (4), 991–997 (1998).

Brinster, R. L. STUDIES ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF MOUSE EMBRYOS IN VITRO. 3. THE EFFECT OF FIXED-NITROGEN SOURCE. J Exp Zool 158, 69–77 (1965).

Nakazawa, T. et al. Effect of different concentrations of amino acids in human serum and follicular fluid on the development of one-cell mouse embryos in vitro. J Reprod Fertil 111 (2), 327–332 (1997).

Devreker, F. et al. Amino acids promote human blastocyst development in vitro. Hum Reprod 16 (4), 749–756 (2001).

Gardner, D. K. & Lane, M. Culture and selection of viable blastocysts: a feasible proposition for human IVF? Hum Reprod Update 3 (4), 367–382 (1997).

Summers, M. C. & Biggers, J. D. Chemically defined media and the culture of mammalian preimplantation embryos: historical perspective and current issues. Hum Reprod Update 9 (6), 557–582 (2003).

Sturmey, R. G., Brison, D. R. & Leese, H. J. Symposium: innovative techniques in human embryo viability assessment. Assessing embryo viability by measurement of amino acid turnover. Reprod Biomed Online 17 (4), 486–496 (2008).

Chason, R. J., Csokmay, J., Segars, J. H., DeCherney, A. H. & Armant, D. R. Environmental and epigenetic effects upon preimplantation embryo metabolism and development. Trends Endocrinol Metab 22 (10), 412–420 (2011).

Kawachiya, S. et al. Blastocyst culture is associated with an elevated incidence of monozygotic twinning after single embryo transfer. Fertil Steril 95 (6), 2140–2142 (2011).

van Montfoort, A. P. et al. Assisted reproduction treatment and epigenetic inheritance. Hum Reprod Update 18 (2), 171–197 (2012).

Hu, S., Loo, J. A. & Wong, D. T. Human body fluid proteome analysis. Proteomics 6 (23), 6326–6353 (2006).

Dobson, A. T. et al. The unique transcriptome through day 3 of human preimplantation development. Hum Mol Genet 13 (14), 1461–1470 (2004).

Hamatani, T., Carter, M. G., Sharov, A. A. & Ko, M. S. Dynamics of Global Gene Expression Changes during Mouse Preimplantation Development. Dev Cell 6 (1), 117–131 (2004).

Wang, Q. T. et al. A genome-wide study of gene activity reveals developmental signaling pathways in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Dev Cell 6 (1), 133–144 (2004).

Gutstein, H. B., Morris, J. S., Annangudi, S. P. & Sweedler, J. V. Microproteomics: analysis of protein diversity in small samples. Mass Spectrom Rev 27 (4), 316–330 (2008).

Jansen, C. et al. Protein profiling of B-cell lymphomas using tissue biopsies: A potential tool for small samples in pathology. Cell Oncol 30 (1), 27–38 (2008).

Katz-Jaffe, M. G., Gardner, D. K. & Schoolcraft, W. B. Proteomic analysis of individual human embryos to identify novel biomarkers of development and viability. Fertil Steril 85 (1), 101–107 (2006).

Katz-Jaffe, M. G., Schoolcraft, W. B. & Gardner, D. K. Analysis of protein expression (secretome) by human and mouse preimplantation embryos. Fertil Steril 86 (3), 678–685 (2006).

Reo, N. V. NMR-based metabolomics. Drug Chem Toxicol 25 (4), 375–382 (2002).

Fernie, A. R., Trethewey, R. N., Krotzky, A. J. & Willmitzer, L. Metabolite profiling: from diagnostics to systems biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5 (9), 763–769 (2004).

Wilson, V. L. & Jones, P. A. DNA methylation decreases in aging but not in immortal cells. Science 220 (4601), 1055–1057 (1983).

Soga, T. et al. Differential metabolomics reveals ophthalmic acid as an oxidative stress biomarker indicating hepatic glutathione consumption. J Biol Chem 281 (24), 16768–16776 (2006).

Villas-Boas, S. G., Mas, S., Akesson, M., Smedsgaard, J. & Nielsen, J. Mass spectrometry in metabolome analysis. Mass Spectrom Rev 24 (5), 613–646 (2005).

Baltz, J. M. & Tartia, A. P. Cell volume regulation in oocytes and early embryos: connecting physiology to successful culture media. Hum Reprod Update 16 (2), 166–176.

Menezo, Y., Renard, J. P., Delobel, B. & Pageaux, J. F. Kinetic study of fatty acid composition of day 7 to day 14 cow embryos. Biol Reprod 26 (5), 787–790 (1982).

Kane, M. T. & Headon, D. R. The role of commercial bovine serum albumin preparations in the culture of one-cell rabbit embryos to blastocysts. J Reprod Fertil 60 (2), 469–475 (1980).

Khandoker, M. A. M. Y., Nishioka, M. & Tsuji, H. Effect of BSA Binding Fatty Acids on Mouse and Rat Embryo Development. J Mamm Ova Res 12, 113–118 (1995).

Fujino, T. et al. Molecular identification and characterization of two medium-chain acyl-CoA synthetases, MACS1 and the Sa gene product. J Biol Chem 276 (38), 35961–35966 (2001).

Bershadsky, A. D., Gelfand, V. I., Svitkina, T. M. & Tint, I. S. Destruction of microfilament bundles in mouse embryo fibroblasts treated with inhibitors of energy metabolism. Exp Cell Res 127 (2), 421–429 (1980).

Eaton, S., Bartlett, K. & Pourfarzam, M. Mammalian mitochondrial beta-oxidation. Biochem J 320 (Pt 2), 345–357 (1996).

Charles, R. & Roe, J. D. Mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation disorder. In Scriver, C.R., Beaudet, A.L., Sly, W.S. and Valle, D. (eds), The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. (McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., New York, 2001).

Uchida, Y., Izai, K., Orii, T. & Hashimoto, T. Novel fatty acid beta-oxidation enzymes in rat liver mitochondria. II. Purification and properties of enoyl-coenzyme A (CoA) hydratase/3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase/3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase trifunctional protein. J Biol Chem 267 (2), 1034–1041 (1992).

Kao, H. J. et al. ENU mutagenesis identifies mice with cardiac fibrosis and hepatic steatosis caused by a mutation in the mitochondrial trifunctional protein beta-subunit. Hum Mol Genet 15 (24), 3569–3577 (2006).

Ibdah, J. A. et al. A fetal fatty-acid oxidation disorder as a cause of liver disease in pregnant women. N Engl J Med 340 (22), 1723–1731 (1999).

Houghton, F. D., Humpherson, P. G., Hawkhead, J. A., Hall, C. J. & Leese, H. J. Na+, K+, ATPase activity in the human and bovine preimplantation embryo. Dev Biol 263 (2), 360–366 (2003).

Wu, F. et al. Uptake of 14C- and 11C-labeled glutamate, glutamine and aspartate in vitro and in vivo. Anticancer Res 20 (1A), 251–256 (2000).

Booth, P. J., Humpherson, P. G., Watson, T. J. & Leese, H. J. Amino acid depletion and appearance during porcine preimplantation embryo development in vitro. Reproduction 130 (5), 655–668 (2005).

Eckert, J. J. et al. Human embryos developing in vitro are susceptible to impaired epithelial junction biogenesis correlating with abnormal metabolic activity. Hum Reprod 22 (8), 2214–2224 (2007).

Houghton, F. D. et al. Non-invasive amino acid turnover predicts human embryo developmental capacity. Hum Reprod 17 (4), 999–1005 (2002).

Hillman, N. & Flynn, T. J. The metabolism of exogenous fatty acids by preimplantation mouse embryos developing in vitro. J Embryol Exp Morphol 56, 157–168 (1980).

Dunning, K. R. et al. Beta-oxidation is essential for mouse oocyte developmental competence and early embryo development. Biol Reprod 83 (6), 909–918 (2010).

Hewitson, L. C., Martin, K. L. & Leese, H. J. Effects of metabolic inhibitors on mouse preimplantation embryo development and the energy metabolism of isolated inner cell masses. Mol Reprod Dev 43 (3), 323–330 (1996).

Tolwani, R. J. et al. Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency in gene-targeted mice. PLoS Genet 1 (2), e23 (2005).

Berger, P. S. & Wood, P. A. Disrupted blastocoele formation reveals a critical developmental role for long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase. Mol Genet Metab 82 (4), 266–272 (2004).

Wang, G. J. T. H. & Khandoker, M. A. M. Y. Fatty Acid Compositions of Mouse Embryo, Oviduct and Uterine Fluid. Anim Sci Technol 69, 923–928 (1998).

Simpson, E. R., Rochelle, D. B., Carr, B. R. & MacDonald, P. C. Plasma lipoproteins in follicular fluid of human ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 51 (6), 1469–1471 (1980).

Sutton, M. L., Gilchrist, R. B. & Thompson, J. G. Effects of in-vivo and in-vitro environments on the metabolism of the cumulus-oocyte complex and its influence on oocyte developmental capacity. Hum Reprod Update 9 (1), 35–48 (2003).

Gardner, D. K., Lane, M., Calderon, I. & Leeton, J. Environment of the preimplantation human embryo in vivo: metabolite analysis of oviduct and uterine fluids and metabolism of cumulus cells. Fertil Steril 65 (2), 349–353 (1996).

Nagy, A., Gertsenstein, M., Vintersten, K. & Behringer, R. Manipulating the Mouse Embryo: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd edition ed. (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2003).

Allen, R. G. & Tresini, M. Oxidative stress and gene regulation. Free Radic Biol Med 28 (3), 463–499 (2000).

Soga, T. & Heiger, D. N. Amino acid analysis by capillary electrophoresis electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 72 (6), 1236–1241 (2000).

Soga, T. et al. Simultaneous determination of anionic intermediates for Bacillus subtilis metabolic pathways by capillary electrophoresis electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 74 (10), 2233–2239 (2002).

Soga, T. et al. Metabolomic profiling of anionic metabolites by capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 81 (15), 6165–6174 (2009).

Hirayama, A. et al. Quantitative metabolome profiling of colon and stomach cancer microenvironment by capillary electrophoresis time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Cancer Res 69 (11), 4918–4925 (2009).

Sugimoto, M., Wong, D. T., Hirayama, A., Soga, T. & Tomita, M. Capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry-based saliva metabolomics identified oral, breast and pancreatic cancer-specific profiles. Metabolomics 6 (1), 78–95 (2010).

Macas, E. et al. Abnormal chromosomal arrangements in human oocytes. Hum Reprod 5 (6), 703–707 (1990).

Nonogaki, T. et al. Developmental blockage of mouse embryos caused by fatty acids. J Assist Reprod Genet 11 (9), 482–488 (1994).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Kenji Miyado, Keiichi Yoshida, Takumi Miura and other members of National Research Institute for Child Health and Development and Keio university school of medicine for stimulating discussion. This work was supported, in part, by Grants-in-Aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Kiban-B-22390312 to TH and Kiban-C-23592415 to TF), by a National Grant-in-Aid from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (NCCHD24-6 to TH and HA), by a Grant-in-Aid from the Japan Health Sciences Foundation (KHD1021 to TH and HA), by Grants-in-Aid from the Kanzawa Medical Research Foundation (to MY) and by Yamagata Prefecture and Tsuruoka City (to TS and MT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MY, KT and TH contributed to the experimental design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation and to drafting of the article. AH and HA provided analysis and data interpretation. TF, SO, KS and TS provided technical support and assisted with the data analysis and interpretation. AU, NK, YY and MT assisted with experimental design as well as data analysis and interpretation. All authors examined the data and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Table

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareALike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yamada, M., Takanashi, K., Hamatani, T. et al. A medium-chain fatty acid as an alternative energy source in mouse preimplantation development. Sci Rep 2, 930 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00930

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00930

This article is cited by

-

The impact of the protein stabilizer octanoic acid on embryonic development and fetal growth in a murine model

Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.