Abstract

Destructive gas generation with associated swelling has been a major challenge to the large-scale application of lithium ion batteries (LIBs) made from Li4Ti5O12 (LTO) anodes. Here we report root causes of the gassing behavior and suggest remedy to suppress it. The generated gases mainly contain H2, CO2 and CO, which originate from interfacial reactions between LTO and surrounding alkyl carbonate solvents. The reactions occur at the very thin outermost surface of LTO (111) plane, which result in transformation from (111) to (222) plane and formation of (101) plane of anatase TiO2. A nanoscale carbon coating along with a stable solid electrolyte interface (SEI) film around LTO is seen most effective as a barrier layer in suppressing the interfacial reaction and resulting gassing from the LTO surface. Such an ability to tune the interface nanostructure of electrodes has practical implications in the design of next-generation high power LIBs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lithium ion batteries (LIBs) have been widely applied in many electronic devices due to their high energy densities, flexible design, light weight and long lifespan compared to other types of batteries, such as Ni-Cd, Ni-MH and lead acid batteries1,2. For the same reasons, they also have been considered as an excellent power source for electric vehicles (EVs) and energy storage stations (ESSs) that require high energy density, long cyclic life and excellent safety performance. At present, various forms of carbons are the dominant source of anode materials for LIBs3,4, which, however, have shown some critical issues, including poor cyclic life, high reactivity with electrolyte solution that easily contribute to the thermal runaways of battery under certain abusive conditions5. Myriad investigations have hitherto been conducted to develop new electrode materials that possess much improved electrochemical and safety performance6,7,8.

Spinel Li4Ti5O12 (LTO) anode has a theoretical capacity of 175 mAhg−1 within the voltage range of 2.5~1.0 V and exhibits excellent reversibility due to its zero volume change during charge/discharge cycles. In addition, LTO demonstrates excellent safety and cyclic performance, making it a potential anode material for high power applications9,10,11. Unfortunately, LTO shows a low intrinsic electronic conductivity and lithium-ion diffusion coefficient12,13, resulting in poor high-rate charge/discharge capabilities. A number of strategies, including carbon coating14,15, metal and nonmetal ion doping13,16,17,18, hybridization with carbon and metal powders19,20,21,22,23, reduction in particle size24 and formation of micro-scale secondary particles consisting of nanostructured primary particles8,13, have been devised to improve the electrochemical performance of LTO anodes with varied success.

Even after a decade of tremendous efforts based on the above approaches25, however, LTO anode is not considered the most preferable choice for large-scale applications by the power LIB industries mainly due to severe gassing during charge/discharge cycles and storage, especially at elevated temperatures26,27. Gassing in lead-acid batteries is known to be caused by overcharging or short circuits inside the battery28,29. However, gassing in LTO-based LIBs is little understood although it leads to serious swelling and hence becomes a grave safety concern, a main obstacle to widespread use of LTO-based batteries. The battery industries are expecting an effective remedy for the gassing problem so as to pave the way for the vast applications of LTO power battery in EVs and ESSs. To date, there are only a few reports that specifically refer to the gassing behavior of LTO electrodes26,27,30,31,32. Very recently, the gas generated inside the LTO/LiMn2O4 cells has been confirmed to mainly consist of H2, CO2 and CO26. It is suggested that H2 is possibly derived from a trace of H2O, while CO and CO2 result from the decomposition of electrolyte solution initiated at relatively high temperatures by PF5 that is a strong Lewis acid and one of the decomposition products of the electrolyte, LiPF626,33,34,35. However, gassing always occurs even when the LTO-based battery is not cycled and only stored at room temperature. Moreover, commercial graphite anodes soaked in LiPF6 electrolyte do not show similar gassing behavior during storage or cyclic test under similar conditions. The above literature survey and practical operational experience clearly indicate that the underlying mechanisms for the formation of these gasses are still unclear and the understanding of the roles of LiPF6 electrolyte in gassing reactions in LTO-based batteries is far from complete.

Here we aim to identify the root causes of gassing in LTO-based batteries and hence to propose effective methods to control it. For these purposes, we designed five experimental conditions (see Table 1 for details). Conditions A, B and C are intended to identify whether the gassing reactions are initiated by PF5 or LTO. Conditions D and E, which are encountered in the practical operation of LIBs, are respectively employed to evaluate gas generation process during storage (fully charged in the formation process) and cyclic tests of soft-packed LTO batteries. The comparative investigations on the above five conditions help reach an understanding of the root causes of the gassing behaviors, that is, interfacial reaction between LTO and electrolyte solution; note that not PF5 but LTO initiates such an interfacial reaction based the gassing process associated with a phase change and the formation of a new phase; and a carbon coating, functioning as a constructive barrier around LTO particles, is effective to suppress the gassing and the resultant swelling of commercial LTO-based batteries.

Results

Gassing behaviors under Conditions A–E

Nano-structured active materials have a high reactivity with electrolyte, making it very difficult to detect the intrinsic reactions taking place between the electrode and electrolyte. Therefore, micro-sized cubic LTO powders were synthesized to study the gassing reactions in this work. The particle size of LTO is ~1 μm as confirmed by the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observations (Supplementary Fig. S1a–b). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the LTO is in good agreement with the JCPDS standard (card No. 49-0207) and can be indexed to the spinel structure of LTO with the space group Fd3m (Supplementary Fig. S1c). Weak diffraction peaks of rutile TiO2 are detected, indicating an existence of small fraction of rutile TiO2 nano-coating that can improve the rate performance of LTO36.

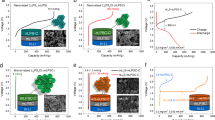

The soft packed NCM/LTO batteries were assembled with Li(Ni1/3Co1/3Mn1/3)O2 (NCM) as the cathode, the LTO prepared above as the anode and 1 M LiPF6/EC+DMC+EMC as the electrolyte solution. Using such soft packed NCM/LTO batteries, the specific capacities of the LTO measured at the 1st and 400th cycles are 148.7 and 138.5 mAh g−1, respectively (Fig. 1a). It is noted that very obvious swelling is observed for the battery after cyclic test under Condition E (Fig. 1e–f). Even the fully charged battery that was only stored at 25°C for 3 months (Conditions D) also presents similar gassing behavior (Fig. 1c–d). It is apparent that the swelling results from the gas generated in the soft packed batteries. The rate of gassing gradually decreases with increasing the storage and cyclic period.

Cyclic and storage performance of NCM/LTO and NCM/(LTO/C) batteries under Conditions D and E. (a, b) Performance curves at 0.5C/0.5C and 25°C (Condition E).

Photographs of soft-packed NCM/LTO batteries (c) before and (d) after storage under Condition D and (e) before and (f) after cyclic test under Condition E. Photographs of soft-packed NCM/(LTO/C) batteries (g) before and (h) after storage under Condition D and (i) before and (j) after cyclic test under Condition E. Note that swelling caused by gassing is observed in the NCM/LTO batteries (arrows (↑) labels the obviously swollen areas), but not in the NCM/(LTO/C) batteries.

As presented above, five conditions were designed to simulate the gassing process between LTO and electrolyte (See Table 1 for details). Interestingly, obvious swelling also occur when LTO or rutile TiO2 is soaked in solvents (Condition A) or electrolyte solution (Condition B) (not subject to any electrochemical process), whereas there is no obvious swelling when there is only electrolyte solution in the absence of LTO or rutile TiO2 (Condition C). This difference can be clearly identified from the volume of gas generated under Conditions A, B and C (Fig. 2e). The above results indicate that the gassing behaviors are intimately related to LTO or rutile TiO2.

Schematics of gassing behaviors of LTO electrodes with electrolyte under different conditions.

(a) CO2 is generated when LTO is soaked under Conditions A and B. (b) The surface of LTO is covered by solid electrolyte interface (SEI) film consisting of the reaction products of LTO with solvents or electrolyte solution and the phase change occurs at the outermost surface of LTO soaked under Conditions A and B. Note that the components of SEI film formed under Conditions A and B is obviously different. (c) Gaseous H2, CO2 and CO are generated when NCM/LTO batteries are stored and cycled under Conditions D and E. (d) The surface of LTO is covered by a SEI film consisting of the reaction products of LTO with electrolyte under Conditions D and E and phase change occurs at the outermost surface of LTO. Not that the thickness of SEI film under Conditions D and E are obviously different. (e) Volumes of gas generated when LTO or rutile TiO2 is soaked under Conditions A, B and C.

The gas components were analyzed by gas chromatograms and the results are summarized in Table 2 and Table S1. The gassing behaviors of LTO with electrolyte solution or solvent under different conditions are schematically depicted in Fig. 2a–d. CO2 is the only component generated when LTO is soaked under Conditions A and B, whereas H2, CO2, CO and a trace of gaseous hydrocarbons are generated when the NCM/LTO batteries are stored (Condition D) and cycled (Condition E) where H2 fraction is over 50 wt%. Note that H2 and CO are generated in the batteries that were subjected to charge/discharge cyclic test, suggesting that the charged LTO promotes the generation of H2 and CO which are driven by electrochemical reactions.

PF5, a strong Lewis acid and one of the decomposition products of LiPF6, has been mistakenly considered as the major source of initiating the gassing reactions in the presence of trace amount of water26,33. In sharp contrast, our observation indicate that gassing always occurs even when LTO is soaked in solvents under Condition A (totally free from LiPF6) and CO2 is the only gas component (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Table S1). That is to say that PF5 originated from LiPF6 is not mainly responsible for the generation of CO233,34. As discussed above, much less gassing occurs under Condition C (totally free from LTO or rutile TiO2) as compared to the cases under Conditions A and B. It is therefore concluded that CO2 generation is mainly attributed to the intrinsic reaction between LTO or rutile TiO2 and alkyl carbonate solvents. Unexpectedly, the volume of gas generated of LTO or rutile TiO2 soaked under Condition A is obviously larger than that under Condition B, although the component of gas is exactly the same (CO2) (Fig. 2e). This further indicates that LiPF6 does not favor the gassing reactions, but rather suppresses it to a certain extent (details will be discussed below).

As is expected, the reactivity of solvents and electrolyte solutions with LTO or rutile TiO2 at 50°C is higher than that at 25°C, which suggests that the higher temperature also promote the above reactions. This can explain why the LTO-based battery is easily swelling at high temperature. For the same reason, we discuss in details the LTO soaked in solvent or electrolytes at 50°C to image the gassing behaviors more distinctly.

The volume of the generated gas as demonstrated in Fig. 2e also indicates that the reactivity of rutile TiO2 with electrolyte is apparently lower than that of LTO counterpart. In view of the above findings and a very small amount of rutile TiO2 contained in LTO, the swelling of NCM/LTO batteries is mainly ascribed to the intrinsic reactions of LTO with electrolyte solution.

Carbon coating to suppress gassing in NCM/LTO battery

Here, carbon coating is employed as a thin barrier layer to control the gassing reaction by isolating the LTO particles from electrolyte solution. Carbon coated LTO (LTO/C) was prepared (see Methods) and its XRD pattern is in good agreement with the JCPDS file (card No. 49-0207) (Supplementary Fig. S3a). Low diffraction peaks of rutile and anatase TiO2 are observed and LTO/C has a well-defined crystal structure with a particle size of around 300 nm (Supplementary Fig. S3b–e). The Raman spectra of LTO/C indicate that the carbon is mainly amorphous judging from the high the intensity ratio (ID/IG = 2.99) of D- and G-band peaks (Supplementary Fig. S4a). Based on the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), the carbon content is roughly estimated to be ~3.0 wt % (Supplementary Fig. S4b).

The soft-packed NCM/(LTO/C) batteries were prepared using LTO/C as the anode and the specific capacities measured after the 1st and 400th cycles at 0.5C/0.5C are 151.2 mAhg−1 and 151.3 mAhg−1, respectively (Fig. 1b). These values present much higher cyclic stability than the corresponding values of the uncoated LTO (Fig. 1a), testament to the beneficial effect of the carbon coating. In particular, no visible swelling occurs for the LTO/C-based battery after storage and cyclic test under both Conditions D and E (Fig. 1g–j) unlike the uncoated LTO batteries (Fig.1c–f). This observation suggests that the carbon coating is very effective in suppressing the gassing behavior of LTO batteries.

Note that both the LTO and LTO/C-based batteries were prepared using the same condition. No apparent gassing occurs in the LTO/C-based batteries, indicating that H2 is not generated in the LTO/C-based batteries unlike the LTO-based batteries. This observation further hints that H2 generated in LTO-base batteries is not caused by the reactions of Li ions (or Li metal) with the trace H2O (or HF) that are present in both LTO-based and LTO/C-based batteries33. This means that the gassing based swelling of LTO-based batteries originates from the intrinsic reactions of electrolyte and LTO subjected to charge/discharge cyclic test.

Based on the above results, we can conclude that the gas generated in the swollen LTO-based batteries originates from the intrinsic reactions between the electrolyte solution and LTO and is hardly related to PF5 and H2O. In the next section, the gassing reaction mechanisms of LTO with electrolyte solution under different conditions are discussed in more detail and the role of carbon coating in suppressing the gassing behavior of LTO batteries is elucidated.

Discussion

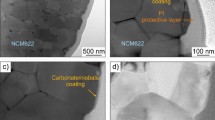

Gassing processes of LTO in presence of alkyl carbonate solvents under different conditions are discussed in details as follows. LTO soaking in electrolyte-free solvent (DEC as a typical solvent for Condition A) is discussed at first. The original LTO has a well-defined crystal structure as indicated by the high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image (Fig. 3a) and the d-spacing of 0.489 nm is in agreement with that of the (111) plane of spinel LTO. After LTO was soaked in DEC (totally free from LiPF6 as electrolyte), an apparent phase change occurs to the outermost surface and a very thin layer (3 nm in thickness) is unexpectedly formed around the LTO particles, which is totally different from the interior crystalline structure of the (111) plane (Fig. 3b)32. The d-spacing of the newly formed surface layer is 0.241 nm which matches well with that of the LTO (222) plane, indicating a transformation of the (111) plane to (222) plane at the outermost surface. Moreover, a new phase of the anatase TiO2 (101) plane with d-spacing of 0.357 nm is observed simultaneously (Fig. 3c). Judging from the absence of anatase TiO2 in the as-prepared LTO, the anatase TiO2 is also the result from soaking.

TEM images of LTO and LTO/C electrodes.

(a) As-prepared LTO. (b, c) LTO soaked under Condition A (DEC at 50°C). (d) LTO soaked under Condition B (1 M LiPF6/EC+DMC+EMC at 50°C). (e) LTO in fully charged NCM/LTO battery stored under Condition D. (f) LTO in NCM/LTO battery cycled under Condition E. (g) As-prepared LTO/C. (h) LTO/C in fully charged NCM/(LTO/C) battery stored under Condition D. (i) LTO/C in NCM/(LTO/C) battery cycled under Condition E. Note that the LTO and LTO/C batteries tested under Conditions D and E were fully discharged before TEM examination.

The Ti 2p and O 1s X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of LTO obtained before and after soaking further prove the formation of TiO2 (Supplementary Fig. S5b and g). The C 1s spectrum of LTO after soaking presents three small typical peaks at 285.4, 286.5 and 288.9 eV, which can be assigned to C-C, C-O and O-C = O groups (Supplementary Fig. S5l), respectively37,38,39. The peak assigned to lithium carbonates (Li2CO3 and ROCO2Li) at 290.5 eV is not detected38. Furthermore, only CO2 generated during soaking suggests that a decarboxylation reaction of DEC occurs at the interface between LTO and solvent.

The spinel crystallographic structure of LTO presents that the LTO (222) plane is composed only of [Li1/3Ti5/3] layers, while the (111) plane is composed of Li+, O2− and [Li1/3Ti5/3] ions layers (Supplementary Fig. S7a–g). The plane transformation of LTO from (111) to (222) and the formation of anatase TiO2 suggest that the Li+ and O2− ions at outermost surface of LTO are taken away during the interfacial reaction between LTO and DEC, which is associated with the generation of CO2 and the formation of a titanium-rich surface layer32. The XRD patterns suggest that LTO maintains its spinel structure after soaking (Supplementary Fig. S8b) and there are no obvious anatase TiO2 peaks, indicating that only a very thin outermost surface layer of LTO takes part in the interfacial reaction and transforms to the anatase TiO2 (101) plane.

Therefore, the above discussion suggests that the decarboxylation reaction associated with CO2 generation is initiated by the terminated ions of LTO (111) plane, which results in the plane transformation from (111) to (222) and the formation of a new phase, anatase TiO2 (101) plane. The possible reaction mechanism is described in Figure 4a33: the terminated Ti4+ ions of LTO coordinate with the unshared electron pairs of O2− ions of carbonyl groups, while the outermost surface O2− ions of LTO attack the carbon atom of CH3CH2O group and the flexible Li+ ions coordinate with O2− of CH3CH2O group. This reaction gives rise to the formation of CO2, CH3COOLi, anatase TiO2 (101 plane) and C2H5OC2H5. The LTO is covered by a thin SEI film after soaking (Fig. 3b–c), which in turn separates the LTO from the surrounding DEC solvent and reduce to a certain extent the reactivity between LTO and solvent.

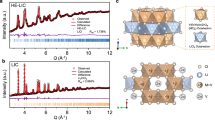

Similar gassing behaviors occur to LTO soaked in electrolyte solution (1 M LiPF6/ EC+DMC+ EMC as an example for Condition B). The XRD pattern and HRTEM images show that the anatase TiO2 (101) plane appeared in the LTO after soaking under Condition B (Figs 3d and 5c). However, both microstructure and surface chemistry of LTO are quite different under these two conditions (Supplementary Fig. S5h and 5m). Due to the existence of LiPF6, Li2TiF6 (JCPDS file of card No. 24-0662) was formed as a result of the reactions between HF and LTO (or anatase TiO2) (Fig. 5c)26,40. In addition, a large amount of LiF (JCPDS file of card No. 04-0857) was formed on the surface of LTO, arising from the decomposition of LiPF6 at around 50°C. The LTO surface was covered by Li2TiF6 and LiF, making the reaction of LTO with surrounding solvents difficult. This is the main reason why the addition of LiPF6 in the solvents reduces the reactivity of LTO with electrolyte and somewhat retards the gassing reactions.

XRD patterns of LTO and LTO/C.

(a) As-prepared LTO. (b) LTO after soaking under Condition A (DEC at 50°C). (c) LTO after soaking under Condition B (1 MLiPF6/EC+DMC+EMC at 50°C). (d) LTO in fully charged NCM/LTO battery stored under Condition D. (e) LTO in NCM/LTO battery cycled under Condition E. (f) As-prepared LTO/C. (g) LTO/C in fully charged NCM/(LTO/C) battery stored under Condition D. (h) LTO/C in NCM/(LTO/C) battery cycled under Condition E. Note that the NCM/LTO and NCM/(LTO/C) batteries tested under Conditions D and E were fully discharged before the XRD analysis.

The O 1s XPS profile presents a large peak at 532.4 eV which is assigned to C-O-C species, while two small peaks at 531.7 and 533.5 eV are attributed to the C = O species and the oxygen atom of lithium alkyl carbonates bounding to two carbon atoms, respectively41,42 (Supplementary Fig. S5h). The C 1s detailed spectrum indicates that the C-O species are the main reaction products between LTO and electrolyte solution. The peaks assigned to carbonates are hardly detected (Supplementary Fig. S5m). The FTIR spectrum (Supplementary Fig. S6d) of LTO after soaking presents three main peaks at 1634, 1167 cm−1 and 1024 cm−1, which are associated with C = O, C-O-C and ROLi species, respectively and these results are in accordance with the XPS results. Only CO2 is generated during LTO soaking under Condition B as a result of the decarboxylation reactions of solvents, similarly to Condition A (DEC). These reactions are also associated with the removal of Li+ and O2− ions at the outermost surface of LTO leading to the formation of (222) plane and anatase TiO2 (101) plane (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. S8f). In view of the formation of many C-O-C species on the surface of LTO after soaking under Condition B, LTO may initiate the ring-opening polymerization of EC, which results in the formation of PEO-like oligomers (-CH2-CH2-O-)n and CO2 (Figure 4b)33,43.

The reacted surface of LTO is also covered by a SEI film with ~2 nm in thickness resulting from the interfacial reaction, which is much thicker than that of LTO soaked under Condition A (Fig. 3b). Based on the above analysis, the components and the thickness of the SEI film formed at the surface of LTO under Condition B are quite different from that subjected to Condition A. With the exception of the decomposition products of solvents, Li2TiF6 and LiF formed on LTO under Condition B can further separate the LTO from the surrounding solvents thereby leading to an obviously less reactivity of LTO in electrolyte solution than in LIPF6-free solvents.

After NCM/LTO batteries were subjected to storage and cyclic tests (Conditions D and E), similar gassing behaviors were found as expected. The (111) plane at the outermost surface of LTO transforms to (222) plane, which is covered by a thin SEI film formed by the products derived from the interfacial reaction between LTO and electrolyte solution when LTO batteries were subjected to Conditions D and E (Fig. 3e–f). The thicknesses of the phase-change layers (from (111) to (222) plane) for LTOs under both conditions (storage and cyclic test) are almost the same (~3 nm), which are, interestingly, similar to that of the LTO soaked under Condition A. It is thought that the phase-change occurs only in a very thin surface layer (~3 nm). As discussed above, the phase change is attributed to the loss of Li+ and O2− ions from the (111) plane by the interfacial reactions between LTO and electrolyte solution. Both the phase-change surface along with newly formed (222) plane and the SEI film formed on top of the phase-change surface become the barrier to separate the LTO from the surrounding electrolyte solution, which can restrain the further interfacial reactions and loss of Li+ and O2− ions from the interior part of LTO. Therefore, it is said that the interfacial reactions between LTO and electrolyte solution mainly occur at the early stage of the storage or cyclic test. As such, the gassing rate gradually decreases as storage and cyclic test continue.

The XRD patterns show that the LTO electrodes tested under Condition D or E maintain the original spinel structure (Supplementary Fig. S8c). However, the XPS (Ti 2p and O 1s) spectra offer no information for unreacted LTO, a strong evidence of the reacted LTO particles being covered completely by the SEI film of reaction products (Supplementary Fig. S5d–e and S5i–j). The detailed XPS results (C 1s) and FTIR spectra indicate that the C-O species are the main components of the SEI film on LTO after storage and cyclic test, which is similar to that of LTO soaked under Condition B (Supplementary Figs S5m–o and S6e–f).

However, it should be mentioned that the formation mechanism of SEI film on LTO electrode is totally different from that on graphite anode. The formation of SEI film on graphite anode is attributed to the reduction reaction of electrolyte solution (~0.7 V) along with gassing and Li2CO3 and ROCO2Li are the main components44,45. Because the reduction potential of most solvents is ~0.7 V, the reduction reaction of electrolyte solution occurs rapidly when the graphite anode is discharged to below 0.7 V. Thus, the formation of SEI film only occurs in the first several cycles during the battery formation and stops in the following cycling. After formation, the gassing behavior stops in the graphite anode battery due to a stable and complete SEI film can separate the graphite from electrolyte solution and suppress the reduction decomposition of electrolyte.

In contrast, the formation of SEI film on LTO is resulted from the interfacial reactions between LTO and electrolyte solution, not the reduction of the electrolyte solution. The rate of interfacial reactions in LTO batteries is much lower than that of the reduction reaction of electrolyte solution in graphite-based batteries and therefore a complete SEI film cannot be formed on LTO electrode during the battery formation process like the case of graphite electrode. Thus, the interfacial reaction further occurs during battery cycling test and long-term storage, which results in the continuous gas-release. The SEI film on LTO electrode is formed gradually with the processing of interfacial reaction, which leads to the decrease in the continuous gassing rate of LTO based battery accordingly. Moreover, the SEI film formed on the surface of LTO after the cyclic test under Condition E is much thicker than that LTO after storage under Condition D. It is well-known that the electrolyte solution is consumed during the battery cyclic tests gradually increasing the SEI film thickness.

Gases such as H2, CO2 and CO were generated under both Conditions D and E. CO2 is derived from the decarboxylation reactions of solvents, similarly to Conditions A and B. As discussed above, H2 does not arise from the reactions of Li ions (or lithium metal) with H2O (or HF). The alkyl groups in alkyl carbonate are the only species that can provide the H proton in the battery. Therefore, the dehydrogenation of the alkoxy group in solvents may be promoted by LTO subjected to charge/discharge cycles and are responsible for the generation of H2. The intermediates of solvent dehydrogenation can further accept electrons and Li ions leading to the decarbonylation reactions and generation of CO46. The possible reaction mechanism is described in Figure 4c. CO2 can also be reduced to form CO according to Figure 4d33,46,47,48. Therefore, it can be concluded that the LTO electrodes induce decarbonylation, decarboxylation and dehydrogenation reactions of solvents, directly accountable for gassing in LTO batteries.

Carbon coating around LTO is found as an effective method to suppress the gassing behavior of NCM/LTO batteries. The d-spacing measured from the HRTEM image of the as-prepared LTO/C is 0.481 nm (Fig. 3g), which matches well with the (111) plane of spinel LTO. The HRTEM images suggest that the LTO surface (e.g. the (111), (222) and (400) planes) is covered by a ~5 nm thick carbon layer (Fig.3g and Supplementary Fig. S3d–e).

The XRD patterns of LTO/C after cyclic and storage tests (Conditions D and E) indicate the formation of LiF, which was absent in the cases of the uncoated LTO electrode as discussed above (Fig. 5d–e and 5g–h). The formation of LiF as an important SEI component is thought to be the consequence of the reaction between PF5 and Li2CO3 that is easily formed on the coated carbon surface during the battery first charge/discharge cycle, as reported previously44 and can stabilize the interface of carbon and electrolyte. In addition, the electric conductance of electrode is highly improved by the coating carbon. It is well-known that the formation of SEI film requires many electrons for decomposition of electrolyte solution. Thus, the high conductance of coating carbon favors an excellent and complete SEI formation, which can further protect the LTO from interfacial reactions.

The XPS spectra (O 1s and C 1s) and FTIR spectra of LTO electrodes indicate that the RCO3Li, C-O-C and ROLi species in the SEI film were formed on the surface of LTO/C after battery storage (Condition D) and cyclic test (Condition E) (Supplementary Figs. S6h–i and S10g–h and k–l). That is, the carbon coating together with the stable SEI film formed on top of the carbon coating as a barrier layer may offer significant synergy to protect the LTO electrode from the surrounding electrolyte solution, eliminating the possible interfacial gassing reaction49.

The HRTEM images exhibited that the morphologies of the interface between LTO and carbon coating hardly changed under Conditions D and E , proving a stable interface existing between them (Fig. 3h–i). Therefore, it can be said that carbon coating is an effective strategy to fully suppress the interfacial reaction and gassing on the LTO surface.

In summary, the gassing phenomenon in LTO electrodes has been one of the most serious obstacles to their large-scale applications in LIBs. PF5, as a strong Lewis acid of decomposition product of LiPF6, has been erroneously regarded as a major source for gassing in the presence of trace amount of water. This paper clarifies that the gassing reactions, including decarboxylation, decarbonylation and dehydrogenation reactions of solvents, are initiated not by PF5, but by LTO on the outermost surface of LTO (111) plane. The interfacial reactions between LTO and electrolyte solution generate gasses like H2, CO2 and CO, which are the main sources for swelling of battery pack. The gassing involves the plane transformation of LTO from (111) to (222) and the formation of (101) plane of anatase TiO2 and the outermost surface Li+ and O2− ions of the LTO (111) plane are removed from LTO by the interfacial reactions.

Constructing a barrier layer is an effective strategy to control the interfacial reactions between LTO and the surrounding electrolyte solution and a nanoscale carbon coating on LTO is proven to suppress the gassing of LTO batteries. The coated carbon, together with the stable SEI film formed around the coating offer significant synergy to separate LTO from the surrounding electrolyte solution and prevent the interfacial gassing reactions. The modification of LTO surface is a simple yet very effective strategy, which can both improve the high-rate charge/discharge performance of batteries and suppress the gassing behavior of LTO battery.

Methods

Synthesis of rutile TiO2, LTO and LTO/C

Rutile TiO2 was obtained by sintering the precursor amorphous TiO2 at 900°C for 8 h. The LTO powder was synthesized by solid-state reaction of the mixture containing amorphous TiO2 with Li2CO3 in air. The TiO2 and Li2CO3 were mixed at a Li:Ti molar ratio of 4.2:5. Carbon coated LTO (LTO/C) composites were also prepared based on a similar solid-state reaction using the precursor mixture plus glucose in argon atmosphere. The details of the synthesis route can be found elsewhere49,50.

Preparation of soft-packed NCM/LTO batteries

Commercial 034352 type soft packed NCM/LTO batteries, of dimensions 3 mm thick, 43 mm wide and 52 mm long, were assembled to investigate the gassing behaviors of LTO batteries. The batteries were made of Li(Ni1/3Co1/3Mn1/3)O2 (NCM) (Tianjiao Technology, Shenzhen, China) as the cathode, as- prepared LTO or LTO/C as the anode, polyethylene as the separator and 1 M LiPF6/EC+DMC+EMC as the electrolyte solution. The NCM cathode consisted of 85 wt.% NCM, 9 wt.% Super-P and 6 wt.% poly(vinylidene fluoride)(PVDF) binder, whereas the LTO anode consisted of 80 wt.% LTO, 10 wt.% Super-P and 10 wt.% PVDF. These components were rolled together to form the battery core and assembled into aluminum-plastic laminated film packages. Batteries were charged and discharged three times between 1.5 and 2.8 V at a rate of 0.5C for stabilization before storage and cyclic tests under Conditions D and E.

Gassing behaviors (Conditions A–E)

As demonstrated in Table 1, five different conditions were designed to clarify the root causes of the gassing behaviors and the gases generated under all these conditions were analyzed on a gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890A GC System) using the GB/T 9722-2006 method.

Conditions A and B: LTO (or rutile TiO2) soaked in electrolyte-free solvent or electrolyte solution

1.6 g of LTO or rutile TiO2 powders was put into aluminum-plastic laminated film packages and 4 mL LiPF6-free solvent or LiPF6-based electrolyte solution was added before sealing of the packages in an argon-filled glove box (See Table 1 for details of the solvents and electrolytes used). The electrode packages were stored at 25 or 50°C for 3 months. The volumes of the packages before and after storage were monitored using the water displacement method.

Condition C

Electrolyte solution (1 M LiPF6/EC+DMC+EMC) stored at 25 or 50°C for 3 months in the absence of LTO. This condition is designed to evaluate the role of LiPF6 in the gassing reactions.

Condition D: Storage test of soft-packed NCM/LTO or NCM/(LTO/C) batteries

The assembled fully charged batteries were stored at 25°C for 3 months.

Condition E: Cyclic test of soft-packed NCM/LTO or NCM/(LTO/C) batteries

The assembled batteries were measured for 400 cycles at a charge/discharge rate of 0.5C (0.5C/0.5C) at 25°C.

Characterization of structure and morphology changes of LTO and LTO/C under different conditions

The LTO and LTO/C electrode materials were rinsed after tests using DMC to remove the electrolyte and dried in the glove box antechamber to remove the residual DMC. XRD patterns of the samples were obtained on a diffractometer (Rigaku D/max 2500/PC) using Cu Kα radiation. The morphologies were examined using a TEM (JOEL JEM-2100F, Japan). XPS measurements were conducted using Physical Electronics PHI5802 instrument using X-rays magnesium anode (monochromatic Kα X-rays at 1253.6 eV) as the source. The C 1s region was used as a reference and was set at 284.8 eV.

References

Tarascon, J.-M. & Armand, M. Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature 414, 359–367 (2001).

Dunn, B., Kamath, H. & Tarascon, J. M. Electrical Energy Storage for the Grid: A Battery of Choices. Science 334, 928–935 (2011).

Kaskhedikar, N. A. & Maier, J. Lithium Storage ion Carbon Nanostructures. Adv. Mater. 21, 2664–2680 (2009).

Liu, C., Li, F., Ma, L. P. & Cheng, H. M. Advanced Materials for Energy Storage. Adv. Mater. 22, E28–E62 (2010).

Spotnitz, R. & Franklin, J. Abuse behavior of high-power, lithium-ion cells. J. Power Sources 113, 81–100 (2003).

Jung, H. G., Jang, M. W., Hassoun, J., Sun, Y. K. & Scrosati, B. A high-rate long-life Li4Ti5O12/Li[Ni0.45Co0.1Mn1.45]O4 lithium-ion battery. Nat. Commun 2 (516), 511–515 (2011).

Kang, K. S., Meng, Y. S., Breger, J., Grey, C. P. & Ceder, G. Electrodes with high power and high capacity for rechargeable lithium batteries. Science 311, 977–980 (2006).

Amine, K. et al. Nanostructured Anode Material for High-Power Battery System in Electric Vehicles. Adv. Mater. 22, 3052–3057 (2010).

Ferg, E., Gummow, R. J., Kock, A. d. & Thackeray, M. M. Spinel Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 141, L147–L150 (1994).

Ohzuku, T., Ueda, A. & Yamamoto, N. Zero-Strain Insertion Material of Li[Li1/3Ti5/3]O4 for Rechargeable Lithium Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 142, 1431–1435 (1995).

Aldon, L. et al. Chemical and Electrochemical Li-Insertion into the Li4Ti5O12 Spinel. Chem. Mater. 16, 5721–5725 (2004).

Li, B. H. et al. Facile synthesis of Li4Ti5O12/C composite with super rate performance. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 9595–9602 (2012).

Zhao, L., Hu, Y. S., Li, H., Wang, Z. X. & Chen, L. Q. Porous Li4Ti5O12 Coated with N-Doped Carbon from Ionic Liquids for Li-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 23, 1385–1388 (2011).

Wang, G. J. et al. Preparation and characteristic of carbon-coated Li4Ti5O12 anode material. J. Power Sources 174, 1109–1112 (2007).

Zhu, G.-N. et al. Carbon-coated nano-sized Li4Ti5O12 nanoporous micro-sphere as anode material for high-rate lithium-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 4016–4022 (2011).

Park, K. S., Benayad, A., Kang, D. J. & Doo, S. G. Nitridation-Driven Conductive Li4Ti5O12 for Lithium Ion Batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 14930–14931 (2008).

Ji, S. Z. et al. Preparation and effects of Mg-doping on the electrochemical properties of spinel Li4Ti5O12 as anode material for lithium ion battery. Mater. Chem. Phys. 123, 510–515 (2010).

Tian, B., Xiang, H., Zhang, L., Li, Z. & Wang, H. Niobium doped lithium titanate as a high rate anode material for Li-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 55, 5453–5458 (2010).

Huang, S. H., Wen, Z. Y., Zhu, X. J. & Gu, Z. H. Preparation and electrochemical performance of Ag doped Li4Ti5O12 . Electrochem. Commun. 6, 1093–1097 (2004).

Li, X., Qu, M. Z., Huai, Y. J. & Yu, Z. L. Preparation and electrochemical performance of Li4Ti5O12/carbon/carbon nano-tubes for lithium ion battery. Electrochim. Acta 55, 2978–2982 (2010).

Li, X., Qu, M. Z. & Yu, Z. L. Preparation and electrochemical performance of Li4Ti5O12/graphitized carbon nanotubes composite. Solid State Ionics 181, 635–639 (2010).

Cai, R., Yu, X., Liu, X. & Shao, Z. Li4Ti5O12/Sn composite anodes for lithium-ion batteries: Synthesis and electrochemical performance. J. Power Sources 195, 8244–8250 (2010).

Zhang, B. et al. Urchin-like Li4Ti5O12-carbon nanofiber composites for high rate performance anodes in Li-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 12133–12140 (2012).

Borghols, W. J. H., Wagemaker, M., Lafont, U., Kelder, E. M. & Mulder, F. M. Size Effects in the Li4+xTi5O12 Spinel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 17786–17792 (2009).

Zhu, G. N., Wang, Y. G. & Xia, Y. Y. Ti-based compounds as anode materials for Li-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 6652–6667 (2012).

Belharouak, I. et al. Performance Degradation and Gassing of Li4Ti5O12/LiMn2O4 Lithium-Ion Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 8, A1165–A1170 (2012).

Wu, K., Yang, J., Zhang, Y., Wang, C. & Wang, D. Investigation on Li4Ti5O12 batteries developed for hybrid electric vehicle. J Appl Electrochem. DOI 10.1007/s10800-012-0442-0 (2012).

Yang, Z. et al. Electrochemical Energy Storage for Green Grid. Chem. Rev. 111, 3577–3613 (2011).

Hammouche, A., Karden, E., Walter, J. & Doncker, R. W. D. On the impedance of the gassing reactions in lead-acid batteries. J. Power Sources 96, 106–112 (2001).

Du Pasquier, A., Plitz, I., Menocal, S. & Amatucci, G. A comparative study of Li-ion battery, supercapacitor and nonaqueous asymmetric hybrid devices for automotive applications. J. Power Sources 115, 171–178 (2003).

Ding, Z. J. et al. Towards understanding the effects of carbon and nitrogen-doped carbon coating on the electrochemical performance of Li4Ti5O12 in lithium ion batteries: a combined experimental and theoretical study. PCCP 13, 15127–15133 (2011).

Lu, X. et al. Lithium Storage in Li4Ti5O12 Spinel: The Full Static Picture from Electron Microscopy. Adv. Mater. 24, 3233–3238 (2012).

Xu, K. Nonaqueous liquid electrolytes for lithium-based rechargeable batteries. Chem. Rev. 104, 4303–4417 (2004).

Sloop, S. E., Pugh, J. K., Wang, S., Kerr, J. B. & Kinoshita, K. Chemical Reactivity of PF5 and LiPF6 in Ethylene Carbonate/Dimethyl Carbonate Solutions. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 4, A42–A44 (2001).

Sloop, S. E., Kerr, J. B. & Kinoshita, K. The role of Li-ion battery electrolyte reactivity in performance decline and self-discharge. J. Power Sources 119–121, 330–337 (2003).

Wang, Y.-Q. et al. Rutile-TiO2 Nanocoating for a High-Rate Li4Ti5O12 Anode of a Lithium-Ion Battery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 7874–7879 (2012).

Leroy, S., Martinez, H., Dedryvere, R., Lemordant, D. & Gonbeau, D. Influence of the lithium salt nature over the surface film formation on a graphite electrode in Li-ion batteries: An XPS study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 253, 4895–4905 (2007).

Dedryvere, R. et al. Electrode/Electrolyte Interface Reactivity in High-Voltage Spinel LiMn1.6Ni0.4O4/Li4Ti5O12 Lithium-Ion Battery. J Phys Chem C 114, 10999–11008 (2010).

Dedryvere, R. et al. Characterization of lithium alkyl carbonates by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy: Experimental and theoretical study. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 15868–15875 (2005).

Janz, G. J., Lorenz, M. R. & Brown, C. T. Preparation and Thermal Stability of Lithium Titanium Fluoride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80, 4126–4128 (1958).

Alfarra, A., Frackowiak, E. & Beguin, F. Mechanism of lithium electrosorption by activated carbons. Electrochim. Acta 47, 1545–1553 (2002).

Zhang, J. H., Maurer, F. H. J. & Yang, M. S. In situ Formation of TiO2 in Electrospun Poly(methyl methacrylate) Nanohybrids. J Phys Chem C 115, 10431–10441 (2011).

Dedryvere, R. et al. XPS identification of the organic and inorganic components of the electrode/electrolyte interface formed on a metallic cathode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 152, A689–A696 (2005).

Dedryvère, R. et al. Surface film formation on electrodes in a LiCoO2/graphite cell: A step by step XPS study. J. Power Sources 174, 462–468 (2007).

Wang, Y. X., Nakamura, S., Ue, M. & Balbuena, P. B. Theoretical studies to understand surface chemistry on carbon anodes for lithium-ion batteries: Reduction mechanisms of ethylene carbonate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 11708–11718 (2001).

Yoshida, H. et al. Degradation mechanism of alkyl carbonate solvents used in lithium-ion cells during initial charging. J. Power Sources 68, 311–315 (1997).

Aurbach, D. et al. The Correlation between the Surface-Chemistry and the Performance of Li-Carbon Intercalation Anodes for Rechargeable Rocking-Chair Type Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 141, 603–611 (1994).

Aurbach, D., Markovsky, B., Weissman, I., Levi, E. & Ein-Eli, Y. On the correlation between surface chemistry and performance of graphite negative electrodes for Li ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 45, 67–86 (1999).

He, Y. B. et al. Carbon coating to suppress the reduction decomposition of electrolyte on the Li4Ti5O12 electrode. J. Power Sources 202, 253–261 (2012).

Ning, F. et al. Effects of TiO2 crystal structure on the performance of Li4Ti5O12 anode material. J. Alloys Compd. 513, 524–529 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank Y. Chen for valuable discussions about reactions Scheme and N. Y. Tang, D. Y. Zhai for valuable comments for this work and we also thank Dongguan Amperex Technology Limited for the help in gas components analysis. This work was supported by National Nature Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51072131, 51202121 and 51232005), Shenzhen Projects for Basic Research (Nos. JC201104210152A and JCYJ20120619152808478), Guangdong Province Innovation R&D Team Plan for Energy and Environmental Materials (No.2009010025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.-H.Y. and F.Y.K. conceived the project and Y.-B.H., B.H.L. and Q.-H.Y. designed the experiments. Y.-B.H. B.H.L. and M.L. carried out the materials synthesis, battery assembly and gases components analysis. C.Z., W.L. and B.Z. performed the structural characterization and components analysis. J.L. constructed the crystal structure model. Y.-B.H., Q.-H.Y., B.H.L., C.Y., H.D.D., J.-K.K. and F.Y.K. discussed the results. Y.-B.H., Q.-H.Y., J.-K.K. and F.Y.K. wrote the initial manuscript which was approved by all the authors.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

He, YB., Li, B., Liu, M. et al. Gassing in Li4Ti5O12-based batteries and its remedy. Sci Rep 2, 913 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00913

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00913

This article is cited by

-

A quantitative and qualitative study of gas generation observed in LiFePO4–TiNb2O7 cells

Journal of Applied Electrochemistry (2024)

-

Effect of Si Doping and Active Carbon Surface Modifications on the Structure and Electrical Performance of Li4Ti5O12 Anode Material for Lithium-Ion Batteries

Ionics (2024)

-

Experimental Study on Combustion Characteristics of Electrolytes and Slurries for Semi-Solid Lithium-ion Flow Battery

Fire Technology (2023)

-

Mimics on Li-ion full-cell fabrication in coin and pouch cell geometries

Bulletin of Materials Science (2023)

-

Characteristics of Li-ion micro batteries fully batch fabricated by micro-fluidic MEMS packaging

Microsystem Technologies (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.