Abstract

Nature has created amazing materials during the process of evolution, inspiring scientists to studiously mimic them. Nacre is of particular interest and it has been studied for more than half-century for its strong, stiff and tough attributes resulting from the recognized “brick-and-mortar” (B&M) layered structure comprised of inorganic aragonite platelets and biomacromolecules. The past two decades have witnessed great advances in nacre-mimetic composites, but they are solely limited in films with finite size (centimetre-scale). To realize the adream target of continuous nacre-mimics with perfect structures is still a great challenge unresolved. Here, we present a simple and scalable strategy to produce bio-mimic continuous fibres with B&M structures of alternating graphene sheets and hyperbranched polyglycerol (HPG) binders via wet-spinning assembly technology. The resulting macroscopic supramolecular fibres exhibit excellent mechanical properties comparable or even superior to nacre and bone and possess fine electrical conductivity and outstanding corrosion-resistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Natural composites of seashell nacre and bones with hierarchical micro- and nano-structures have been studied for at least half-century due to their extraordinary mechanical properties, complemented by unique biological functionalities1,2,3. The microscopic architecture of nacre is depicted as the classic “brick-and-mortar” (B&M) model, which is constituted of highly aligned rigid CaCO3 platelets sub-micrometre thick surrounded by 10–50 nm elastic organic glue layers3,4. Numerous efforts have been addressed to mimic the nacre structure since 19905, using inorganic tablets such as clay6,7,8,9,10, Al2O311,12 and layered double hydroxides (LDH) and organic linear polymers such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)7,8, polyelectrolytes6,9, chitosan10,12 and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA)11. Various strategies have also been developed to fabricate bio-inspired materials, including layer by layer (LbL) deposition6,7,12, freeze-drying assembly11,13,14,15 and vacuum filtration-assisted assembly8,9,10. However, only films and papers with limited size (~cm scale) of nacre mimics have been accessed so far, mainly confined by the substrate-assisted synthetic pathways and the relatively poor solubility/dispersibility of the constituent inorganic particles.

Thus, to achieve the goal of continuous processing for nacre mimics, the synthetic strategy is needed to be reformed and simultaneously the solubility of inorganic platelets must be fundamentally improved, through either reducing their thickness or increasing their surface functional groups. Accordingly, graphene, the thinnest known sheet in the universe16, would be an ideal candidate for the construction of macroscopic biomimetic materials. Besides, graphene possesses marvelous mechanical, electrical and thermally conductive properties17,18, promising wide applications in devices19,20,21 and high-performance composites22,23,24,25. However, either pristine graphene made by mechanical exfoliation of natural graphite or chemically converted graphene (CCG) reduced from graphene oxide (GO) exhibits poor solubility in common solvents and aggregation tendency owing to strong π-π stacking interactions26. To improve the solubility of graphene, laborious efforts on surface functionalization have been made22,23,24,25,27, but highly soluble graphene that can be used in continuous solution-processing has rarely been accessed (the solubility ≤ 7 mg mL−1)26.

Here we firstly choose graphene as rigid platelets and hyperbranched polyglycerol (HPG)28,29 as elastic glue to construct macroscopic biomimetic materials via industrially viable wet-spinning technology. Due to the high solubility as well as abundant functional groups of HPG28,29, the resultant sandwich-like building blocks, HPG-enveloped graphene sheets (HPG-e-Gs), are highly soluble in common solvents such as N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and N-methyl pyrrolidone (NMP) (~50 mg mL−1) and they also can form liquid crystals at high concentrations. The first artificial nacre fibres (ANFs) up to tens of metres in length, with perfect B&M structures of graphene sheets and HPG binders, are continuously spun from their concentrated liquid crystalline (LC) dope. The supramolecular fibres constructed by hydrogen-bonding arrays exhibit eminent properties such as high tensile strength comparable to nacre and bone, fine conductivity and excellent corrosion-resistance.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of HPG-e-Gs

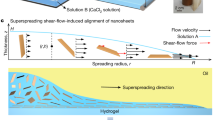

Figure 1 shows our protocol to make ANFs with three steps: (i) synthesis of building blocks, (ii) formation of LC dope and (iii) wet-spinning of ANFs. Four HPG samples with different molecular weights (4.4, 7.2, 87.6 and 125.8 kDa) were used as the organic layers and the corresponding sandwich building blocks were denoted as HPG1-e-G, HPG2-e-G, HPG3-e-G and HPG4-e-G, respectively. The fractions of HPG attached on graphene are 16, 34, 49 and 57 wt% calculated from thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) curves (Supplementary Fig. S1), dependent on the molecular weights. The corresponding hydroxyl densities are 2.11, 4.54, 6.57 and 7.75 mmol g−1, or 35.9, 97.9, 183.3 and 260.5 hydroxyl groups per 1000 carbons of graphene (Table 1), at least twice as high as the functional group density of functionalized graphene reported previously30. Thus, all the HPG-e-Gs exhibit excellent solubility in polar solvents such as DMF and NMP (≥ 5 mg mL−1, Supplementary Fig. S2) due to the strong interactions between the attached functional groups and solvent molecules.

Schematic protocol for making ANFs.

(i) Synthesis of HPG-e-Gs sandwich building blocks via reaction of GO and HPG at 160°C for 18 h. (ii) Pre-alignment of HPG-e-Gs in highly concentrated LC spinning dope. (iii) Formation of hierarchically assembled continuous ANFs via wet-spinning. The supramolecular fibres possessing B&M architecture are assembled from aligned HPG-e-Gs building blocks. We choose HPG as the dendritic polymer glue mainly because narrow polydispersed HPG with different molecular weights can be facilely synthesized by anionic ring-opening polymerization of commercial glycidol. Apart from the attributes of general hyperbranched polymers such as low viscosity, high solubility and plenty of functional groups, HPG is biocompatible, which is favourable for the practical applications of ANFs.

The HPG-e-Gs are totally dispersed as individual nanosheets in solution, as proved by atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurements. Each side of graphene sheet is evenly coated with a layer of HPG protuberances. As a result, the thickness of HPG-e-Gs increases to 2~8 nm from 0.8 nm of GO,which depends upon the molecular weight of HPG (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. S3). The height of HPG-e-Gs reveals the single-layer nature of the coated HPG, which is confirmed by molecular dynamic (MD) simulations. For HPG2-e-G, the simulated diametre of HPG2 unimolecule is 1.04–1.10 nm (Supplementary Fig. S4). The height of HPG2-e-G nanosheets measured by AFM is 3 nm, which is almost equal to the height of GO sheets (0.8 nm) plus the height of two monolayers of HPG2 (2.08–2.20 nm). So HPG2 should be distributed as single layer on both sides of graphene sheets. The high-resolution AFM image shows that the graphene sheet is decorated with HPG molecules uniformly and continuously, with sparsely unoccupied holes sub-100 nm in size (Fig. 2b). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images display that the morphology of freeze-dried HPG-e-Gs changes from grooved/screwed belts tens of micrometres long gradually into individual few-µm “bowls” with increasing the molecular weight of HPG, which is distinct from the relatively stretched morphology of neat GO sheets. This is likely originated from strong cooperative hydrogen bonding among adjacent HPGs upon different thickness of HPG-e-Gs (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Morphology and properties of individual HPG-e-Gs and their filtrated papers.

(a,b), AFM images of HPG4-e-G at different magnifications, showing HPG unimolecules anchored uniformly on graphene sheets, the inset in a shows the height of HPG4-e-G increased to 8 nm. (c) POM image of HPG2-e-G in DMF(~3 mg mL−1) between cross polariers. The dispersion shows giant birefringence of liquid crystals. (d) Photographs of HPG2-e-G in DMF (1 mg mL−1) stayed for 30 days without precipitate. (e) HPG2-e-G in DMF (~20 mg mL−1). (f) HPG2-e-G in DMF (~30 mg mL−1), forming highly viscous semi-gel. (g) HPG2-e-G LC spinning gel (~50 mg mL−1). Upon increasing the concentration, HPG2-e-G dispersions changed from viscous homogeneous liquid (e) to semi-gel with limited mobility (f), then to free-standing gel (g) without precipitates, showing the true solution behavior of HPG2-e-G in a good solvent. Free-standing papers of HPG2-e-G (h, i) and HPG3-e-G (j) made by the classic filtration-assisted assembly method. (k) Stress-strain curves of HPG2-e-G (1) and HPG3-e-G papers (2). (l) Representative SEM image of side-view of HPG2-e-G paper, with perfect layered structures. Scale bars are 2 μm (a), 500 nm ( the inset in a), 100 nm (b), 100 μm (c) and 1 μm (l).

Stability of HPG-e-Gs

The HPG macromolecules are ultra-stable on graphene sheets, which can not be removed by repeated washing with acid (1 M), base (1 M) and LiCl-containing organic solvents, due to the cooperative interactions of hydrogen bonds, ester bonds and possible mechanical interlocking between HPG and graphene (Supplementary Fig. S6). Such a robust character can be further extended to chemical reactions. The hydroxyl groups of HPG-e-Gs were modified with succinic anhydride to obtain carboxyl ones, which could be used to grow superfine platinum nanoparticles 1–2 nm in diametre (Supplementary Fig. S7). Long aliphatic chains were also successfully grafted onto HPG-e-Gs by reacting with palmitoyl chloride, giving rise to well-dispersed, hydrophobic graphene sheets (Supplementary Fig. S6).

HPG-e-G papers

We further investigated the long-term stability of HPG-e-Gs bulk dispersions. HPG with Mn of 7~80 kDa endowed graphene with superior solubility. HPG2-e-G was stable in DMF for at least 30 days without precipitate, whereas tiny precipitates appeared for other dispersions after one week, expressing their different true solubilities (Fig. 2d). Similar to GO31, HPG2-e-Gs can form liquid crystals in highly concentrated true solution (Fig. 2e,f), as shown by polarized optical microscopy (POM) observations (Fig. 2c). Moreover, homogenous gel of HPG2-e-Gs in DMF (~50 mg mL−1) can be easily obtained (Fig. 2g).

Different true solubilities of HPG-e-Gs determine different processing capability. HPG2-e-Gs and HPG3-e-Gs formed strong and flexible films shining metallic luster by vacuum-assisted filtration (Fig. 2h–j), whereas HPG1-e-Gs and HPG4-e-Gs formed continuous but brittle films. Stress-strain tests show that the films of HPG2-e-Gs and HPG3-e-Gs have tensile strength (σ) of 128±30 MPa and 82±10 MPa at ultimate elongations of 1.6~3.0% with Young's modulus (E) of 12.2±3.2 and 9.3±1.5 GPa, respectively (Fig. 2k). Typical B&M layered structures are identified at the fracture section of films (Fig. 2l, Supplementary Fig. S8). The σ of HPG2-e-G film is comparable to those of nacre (130 MPa)1, osteons in bone (102–125 MPa)2, neat graphene papers (150 MPa)32 and GO papers (63.6–130 MPa)33,34, declaring that dendritic polymers with almost null strength can be used as efficient glue to fabricate strong nacre-mimics. Notably, we can readily obtain strong nanocomposites with high content of graphene (~56 wt%) from highly soluble HPG-e-G building blocks. In comparison, layered materials with higher than 7 wt% of graphene have never been accessed before since the mechanical property of composites would be seriously sacrificed as graphene exceed a critical ratio (~6 wt%) in previous reports35.

Continuous ANFs made by wet-spinning

Wet-spinning technology, which is simple, efficient, scalable, economical and green, has been widely used in industry for more than 50 years to make tens of kinds of fibres with millions of tons annually and it has also been utilized to fabricate carbon nanotube (CNT) fibres36,37,38, Kevlar®39, chitosan40 and polyaniline41 fibres. However, this technology has never been tried to spin nacre-mimic fibres, probably because of the poor solubility of inorganic particles and the phase separation between inorganic and organic components in their dispersions. For the first time, we use wet-spinning strategy to capture nacre-mimic fibres from LC dopes of HPG-e-Gs (Supplementary Fig. S9). As the spinning dopes were injected into a coagulation bath (e.g., saturated solution of NaOH in methanol, ethyl acetate, acetone, or their mixture), HPG2-e-Gs procreated flexible and continuous fibres up to tens of metres (Fig. 3a), whereas HPG1-e-Gs and HPG4-e-Gs brought brittle fibres just in centimetre-scale length and HPG3-e-Gs shaped slightly flexible fibres in limited length. The fine flexibility of HPG2-e-Gs fibres promised us to make knots in µm-dimension (Fig. 3b), additionally burdening 3 g clips without breakage (Supplementary Fig. S10). Considering the continuity of the spun fibres, we found that the methanol solution of NaOH was the most favoring bath for spinning HPG2-e-Gs. Upon immersing in the coagulation bath, the wet fibre in gel state consisting of aligned HPG2-e-Gs coagulated and the solvent (DMF) rapidly diffused out of the fibre into the methanol with simultaneous back-diffusing of methanol into the fibre. The flow-induced alignment could be maintained by the NaOH solution that allowed the nanosheets to rapidly stack together as they were coming out of the nozzle. Continuous fibres with 10-100 µm in diametres were then collected onto the spinning drum outside the bath, followed by washing with methanol to remove the residual NaOH. The actual diametres of fibres mainly depended on the nozzle size, injection rate, flow conditions and coagulation procedure.

Morphology of HPG2-e-G fibres.

(a) Photograph of a HPG2-e-G fibre tens of metres long. (b) SEM image of a knot of HPG2-e-G fibre. (c) the wrinkled surface morphology of HPG2-e-G fibre. (d–f) Cross-section SEM images of HPG2-e-G fibre at different magnifications. (g,h) Side view of HPG2-e-G fibre fracture section. The dislocated layered structure (h) indicates displacement of adjacent HPG-e-G building blocks under tension. The dark gray area represents the left interspace after “pulling-out” of some HPG-e-G sheets. (i) Schematic illustration of two neighbored HPG-e-G building blocks glued by the network of hydrogen bonding arrays between them. Scale bars are 200 μm (b), 20 μm (c), 10 μm (d), 3 μm (e), 500 nm (f), 10 μm (g) and 500 nm (h).

The surface of dried fibres shows the orientation of nanosheets along the fibre axis (Fig. 3c) and undee contour is observed in the cross-section (Fig. 3d), caused by the shrinking of dope during the coagulation procedure. Inside the fibres, HPG-e-G hybrid building blocks are found stacking together to form densely ordered lamellar microstructures, resembling the B&M structure of nacre (Fig. 3e,f, Supplementary Fig. S11). So we name it artificial nacre fibres (ANFs). Under low magnification of SEM, we observed curled and folded lamellae, which were ascribed to the dislocation domains in the LC dope (Fig. 3e). To confirm the incorporation of graphene in ANFs, the fibres were further characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and Raman spectroscopy. Similar to the SEM observations, layered structures of black graphene sheets are also identified (Supplementary Fig. S12)6. Raman spectra of ANFs show the characteristic peaks of graphene: the defect-induced D band at ~1,353 cm−1 and G band at ~1,602 cm−1 that is related to in-plane vibration of sp2 carbon atoms in a 2D hexagonal lattice (Supplementary Fig. S13)30. The intensity ratio of D to G band (ID/IG) for ANFs (~1.43), which is related to the size of the sp2 domains30, is close to that (~1.59) of HPG2-e-G building blocks. These results indicate that the chemical structure of graphene hardly changes during the wet-spinning process.

Tensile tests reveal that σ, E and ultimate strain (ε) of ANFs are 125±10 MPa, 8.2±2.2 GPa and ~3.7%, respectively (Fig. 4a). The tensile strength is comparable to those of nacre (130 MPa)1 and osteons in bone (102–125 MPa)2, while the ultimate strain is about 3 folds higher than that of nacre, implying superior toughness of our ANFs. The much better flexibility of ANFs is attributed to the much thinner hard inorganic platelets and self-adapting ability of supramolecular interactions between soft HPG layers during sliding of HPG-e-G building blocks under tension. From the polymer point of view, although HPG2 has null tensile strength as it is a viscous fluid at room temperature with glass translation temperature (Tg) of −48.4°C (Supplementary Fig. S14), its composite fibres demonstrate much greater values of both σ and ε than nacre-like films8,10 (σ ~76–105 MPa, ε ~0.6–0.97%) containing extremely stronger organic layers (~30–50 MPa) of well-known linear chitosan10,12 and PVA7,8,42. This result, together with the aforementioned case of HGP-e-G films, declares that dendritic polymers, even without any strength, can also be employed to construct high strength composites.

The good mechanical performance of our fibres is ascribed to their similar hierarchical structures to nacre43,44,45 and the efficient load transfer between graphene sheets and HPG moieties46,47. At the nanometre scale, protuberances of HPG unimolecules on the graphene sheets (Fig. 2a,b) closely resemble the nanograins on tablets of nacre1,3,4. At the microscale, the wrinkling morphology of graphene sheets is analogous to the waviness of CaCO3 platelets in nacre1,3. In higher level architecture, the alternatively organized graphene and HPG layers corresponds with the classic B&M structure of nacre1,3. Such hierarchical structures conduce to the improvement of mechanical strength. Moreover, the HPG interlayers favor the load transfer between two graphene sheets, spreading the load all over the fibre to increase the tensile strength. This is in accordance with the previous report on composite papers of GO and PVA, which demonstrates the cooperative intersheet hydrogen bonding network between GO and PVA can enhance the load transfer efficiency and increase the mechanical property. The effective load transfer makes the attractive mechanical properties of graphene sheets “survive” in the composite fibres.

Metal ions-crosslinked ANFs

Previous investigations on nanostructures of nacre demonstrated that mineral bridges embedded in the “mortar” layer were not only able to control crack propagation in nacre, but also increase the mechanical performance of the interfaces in the natural layered materials48,49. Divalent ions such as Mg2+ and Ca2+ had also been utilized to cross-link GO sheets for making strong GO papers34. Thus, to further enhance the strength and stiffness of ANFs, we introduced Mg2+ to bridge the adjacent “bricks” by coordinative interactions, mimicking the mineral bridges in nacre. The hydroxyl groups of HPG in HPG-e-G building blocks were firstly converted into carboxyl groups, followed by wet-spinning and immersing in the aqueous ionic solution to afford metal ions-modified ANFs. X-ray energy dispersive analysis proved the uniform distribution of magnesium element in the cross-section of fibres (Supplementary Fig. S15). The resulting Mg2+-modified ANFs show considerably enhanced mechanical strength (σ 145±18 MPa) and stiffness (E 10.0±2.6 GPa), accompanying with fine flexibility (ε ~1.5%) (Fig. 4a). The enhancing effect is resulted from two main factors. First, the coordinative interactions between Mg2+ and carboxyl groups in Mg2+-modified ANFs are stronger than the hydrogen bonds in the unmodified ANFs. Second, the “cavities”46 between neighboring HPG molecules and “defects” at the wrinkles and LC dislocation domains in unmodified ANFs could be filled up with Mg2+ during the ion cross-linking process, further enhancing the mechanical strength of the resulting fibres. Notably, the Mg2+-modified ANFs present superior mechanical performance to GO papers cross-linked by divalent ions of Mg2+ and Ca2+ (σ 80.6–125.8 MPa, ε 0.33–0.50%)34 and poly(allylamine)-crosslinked GO papers (σ 91.9 MPa, ε 0.32%)50 (Fig. 4b), mainly due to crinkling and twisting of graphene building blocks in fibres that can bring additional friction force under tension but rarely occurred on papers of well stacked, flattened GO sheets. Our fibres also exceed nacre (σ 130 MPa, ε 0.9%)1 and artificial nacre films composed of clay and poly(diallydimethylammonium) chloride via LbL assembly (σ 95–109 MPa)6. ANFs with ~34 wt% polymer are even ahead of neat graphene materials in tensile strength. For instance, the tensile strength of Mg2+-modified ANFs is comparable or superior to neat GO fibres (102 MPa)51 and papers (63.6–130 MPa)33,34, as well as reduced graphene fibres (140 MPa)51 and graphene papers (150 MPa)32 (Fig. 4b). In addition, the E of our composite fibres is higher than those of neat GO fibres (5.4 GPa) and reduced graphene fibres (7.7 GPa)51.

Corrosion-resistance and electrical conductivity of ANFs

The chemical resistance of graphene17 and the compact stacked structure of ANFs endue the composites with good corrosion-resisting property. After being immersed in hydrochloric acid (1 M), NaOH (1 M) and saturated LiCl solution in DMF for three days, the ANFs still kept excellent mechanical strength and flexibility (σ ~90–100 MPa, ε ~1–5%) (Fig. 5a) and they were knotted without breakage after being immersed for two weeks (Fig. 5b,c). On the contrary, bubbles were released when nacre was immersed into a hydrochloric acid aqueous solution due to the reaction between CaCO3 tablets and acid (Fig. 5d) and the hard nacre completely disappeared after around one day with a little residue of soft protein membrane (Fig. 5e). Other bio-fibres such as silk and spider silk mostly composed of protein were broken into failed pieces after being immersed in a NaOH aqueous solution for at most three days (Fig. 5f–i).

Corrosion-resistance of ANFs.

Typical stress-strain curves for ANFs after being immersed in different solutions for 3 days (a). The numbers 1, 2 and 3 denote ANFs after being immersed in 1 M HCl, 1 M NaOH and saturated solution of LiCl in DMF, respectively. Photographs of ANFs knots after being immersed in 1 M NaOH (b) and 1 M HCl (c) for two weeks. Photographs of a nacre immersed in 1 M HCl for 0 h (d) and 24 h (e), silk immersed in 1 M NaOH for 0 h (f) and 72 h (g) and spider silk in 1 M NaOH for 0 h (h) and 48 h (i). All of the natural materials have been completely destroyed after being immersed in either acid or basic solution, while our ANFs are still quite strong and robust after being treated with acid and basic aqueous solutions as well as highly polar organic solvent. Scale bars, 3 mm (b,c).

Apart from the extraordinary mechanical performance and corrosion-resistance, our fibres are electrically conductive, with conductivity of ~0.24 S m−1 for ANFs and ~4.88 S m−1 for Mg2+-modified ANFs. As expected, the electrical conductivity is comparable to small molecules-functionalized graphene (0.1–30 S m−1)30 and linear polymer-functionalized graphene (0.84 S m−1)52, but inferior to neat reduced GO papers (170–8100 S m−1)53 and graphene fibres (~2.5×104 S m−1)51. The Mg2+ ions induced the cross-linking of neighboring graphene sheets and partially restored their conjugated networks34, thus the conductivity was improved. In Raman spectra of ANFs (Supplementary Fig. S13), the ID/IG decreases from ~1.43 to ~1.10 after the introduction of Mg2+, suggesting a possible increase in the average size of sp2 domains of graphene sheets30.

Discussion

As shown in Fig. 4a, ANFs exhibit an elastic behavior with small deformation (0–0.5%). At high deformation before breakage (0.5–2.3%), ANFs show a plastic behavior with a relative plateau in the stress-strain curve. This mechanical characteristic is in accordance with the shear lag model for nacre1,3. At the tensile stress less than 50 MPa, the interface between two HPG adlayers, starts to yield in shear and the HPG-e-G building blocks slide on one another, accompanying with the destruction and reformation of the hydrogen-bonding network among HPG macromolecules confined in the intersheet channel. Upon increasing the strain, the load transfers from the soft organic moieties to hard graphene sheets, then the shear spreads all over the fibre, followed by failure of fibre by pullout of HPG-e-G building blocks (Fig. 3g,h, Supplementary Fig. S16). Based on the “pull out” breaking mechanism, the total force in tension (F) could be expressed by F = F1 + F2 = F1 + (f1 + f2), where F1 represents the force provided by the network of hydrogen-bonding between HPG interlayers (Fig. 3i), F2 denotes mechanical friction force between building blocks, which consists of f1 (friction force provided by the rough surface with protuberances of HPG unimolecules on graphene sheets at nanoscale) and f2 (friction force generated by the deformation of flat building blocks such as wrinkling, folding and torsion at micro-scale). Accordingly, the excess mechanical strength of ANFs mainly originates from F2 (or f2), as compared with the previous nacre-mimetic films/papers built with relatively flat and thick inorganic tablets8,10.

On the hydrogen bonding network (F1) between graphene sheets, Buehler and coworkers have made systematic analysis in a joint experimental theoretical and computational study with the example of GO-PVA paper system46. Since the chain entanglement between PVA molecules is not considered (because the degree of polymerization for PVA is 5) in simulations, it is reasonable to introduce the simulations results to our system of graphene and HPG (in which only hydrogen bonding works). The density of hydrogen bonds on graphene sheets in our ANFs is ~3.85 hydrogen bonds nm−2 (Table 1). At the similar situation, the MD simulations show a modulus of 34 GPa for GO-PVA layered papers46, whereas the experimental modulus of our ANFs is only 8.2±2.2 GPa. In fact, there are lots of joints and defects among HPG-e-G sheets in our ANFs that are not considered in the MD simulations, which will be adverse to the mechanical performance. In addition, the MD simulations indicated that ultrahigh tensile strength (~1.7 GPa) could be achieved for the GO-PVA papers46, which suggested that the mechanical performance of graphene-based nacre-mimics could be further improved by optimization of assembly conditions. Furthermore, F1 can be significantly improved by introduction of stronger supramolecular interactions54,55 such as coordination, electrostatic forces6,9 and covalent linkages7,11. On the other hand, the mechanical strength of ANFs can be improved by replacing dendritic polymers with strong linear or crystalline polymers such as PVA7,8, chitosan10,12, cellulose, nylon56 and aromatic polyamides57.

Given the hierarchical structures of ANFs, the mechanical performance can be highly improved by design and optimization of their primary (e.g., size of inorganic sheets and molecular structure of organic glue), secondary (e.g., strong occlusive58/chain entangled/crosslinked7,11 interlayer), tertiary (e.g., regular and compact cross section) and quarternary (e.g., twisting along the fibre axis) structures. Figure 6 shows three kinds of proposed secondary structures, aiming to enhance the interactions of organic molecules between adjacent inorganic layers. First, nano-asperities on the tablets mechanically occlude each other (Fig. 6a), increasing the mechanical friction force under tension. Such structures might be accessible by growing polyaniline nanowires on GO sheets58. Second, the polymer chains on adjacent tablets entangle each other (Fig. 6b), resulting in superhigh van der Waals forces. Third, covalent cross-linking of polymer chains between tablets could also produce ultra-strong and ultra-stiff composites (Fig. 6c). For example, the tensile strength of nacre-like films made by LbL assembly of PVA and clay was enhanced from ~150 to ~400 MPa by cross-linking with glutaraldehyde and the corresponding modulus was increased from ~13 to ~106 GPa simultaneously7.

In conclusion, we have advanced nacre-mimics from limited films to continuous fibres with wide range of promising applications. The macroscopic-assembled fibres possess perfect B&M structures constructed by graphene and HPG and exhibit excellent mechanical property beyond nacre as well as extra corrosion-resistance and good electrical conductivity. We have demonstrated that null strength dendritic polymers could form strong materials through large-area supramolecular arrays, breaking a new path to advanced supramolecular materials. The compositions of bio-mimetic fibres can be extended to other 2D colloids (e.g., clay, LDH, WS2, MoS2, Al2O3 and metalic platelets) and dendritic/linear polymers, expanding the content of both nanocomposite fibres and bio-mimics.

Methods

Preparation of HPG-e-Gs

GO was synthesized from natural graphite powder (40 μm in size, Qingdao Henglide Graphite Co., Ltd.) using the same protocol reported previously30. HPG was synthesized by ring-opening anionic polymerization with potassium methylate as initiator59. GO (200 mg) and HPG (4 g) were dissolved in 200 mL NMP and mixed sufficiently by stirring for 2 h before heating and the homogeneous mixture was slowly heated and maintained around 160°C in a nitrogen atmosphere under constant stirring for 18 h. After being cooled to room temperature, the mixture was separated by repeated centrifugation and washed with DMF for at least four cycles, affording the final products of HPG-e-Gs.

Preparation of HPG-e-Gs papers and fibres

The papers of HPG-e-Gs were prepared by vacuum-assisted filtration of DMF solution with concentration of 5–10 mg mL−1, followed by drying at 80°C in vacuum for 12 h.

For the spinning of HPG2-e-G fibres (Supplementary Fig. S9), the HPG2-e-G dispersion in DMF (25–50 mg mL−1) was loaded into a 1 mL plastic syringe with a spinning nozzle (PEK tube with diametre of 60, 100, 160 μm) and injected into the NaOH/methanol solution by an injection pump (20 μL min−1). After coagulation for 10–15 minutes, the fibres were rolled onto the drum, washed by water to remove NaOH and dried for 24 h under 80°C in vacuum. The spinning process of carboxyl abundant HPG2-e-G fibres was similar to the above procedure except that the coagulation bath was changed to the mixture of acetone and ethyl acetate (1:1 in vol).

Instruments

AFM images were taken in the tapping mode by carrying out on a NSK SPI3800 or a Nanoscope IIIa scanning probe microscope, by spin-coating sample solutions onto freshly cleaved mica substrates at 800 rpm. TGA was carried out on a Perkin-Elmer Pyris 6 TGA instrument with a heating rate of 20°C min−1 under a nitrogen flow (30 mL min−1). SEM images were obtained on a Hitachi S4800 field-emission SEM system. TEM analysis was performed on a JEOL JEM1200EX electron microscope at 120 kV, or a FEI/Philips CM200 electron microscope operating at 200 kV. POM observations were performed with a Nikon E600POL and the liquid samples were loaded into planar cells for observations. FTIR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Vector 22 spectrometer. The tensile stress-strain tests were performed on a Microcomputer Control Electronic Universal Testing Machine made by REGER in China (RGWT-4000-20). The strain rate is 1 mm min−1 with the gauge length of two centimetres. The electrical conductivity of fibres was measured using a four-probe resistivity instrument (RTS-4, PROBES TECH). UV-visible spectra were obtained with a Varian Cary 300 Bio UV-visible spectrophotometer.

References

Yao, H. B., Fang, H. Y., Wang, X. H. & Yu, S. H. Hierarchical assembly of micro-/nano-building blocks: bio-inspired rigid structural functional materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 3764–3785 (2011).

Rho, J. Y., Spearing, L. K. & Zioupos, P. Mechanical properties and the hierarchical structure of bone. Med. Eng. Phys. 20, 92–102 (1998).

Wang, J. F., Cheng, Q. F. & Tang, Z. Y. Layered nanocomposites inspired by the structure and mechanical properties of nacre. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 1111–1129 (2012).

Grégoire, C. Topography of the organic components in mother-of-pearl. J. Biophysic. Biochem. Cytol. 3, 797–808 (1957).

Clegg, W. J., Kendall, K., Alford, N. M., Button, T. W. & Birchall, J. D. A simple way to make tough ceramics. Nature 347, 455–457 (1990).

Tang, Z. Y., Kotov, N. A., Magonov, S. & Ozturk, B. Nanostructured artificial nacre. Nat. Mater. 2, 413–418 (2003).

Podsiadlo, P. et al. Ultrastrong and stiff layered polymer nanocomposites. Science 318, 80–83 (2007).

Walther, A. et al. Large-area, lightweight and thick biomimetic composites with superior material properties via fast, economic and green pathways. Nano. Lett. 10, 2742–2748 (2010).

Walther, A. et al. Supramolecular control of stiffness and strength in lightweight high-performance nacre-mimetic paper with fire-shielding properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 6448–6453 (2010).

Yao, H. B., Tan, Z. H., Fang, H. Y. & Yu, S. H. Artificial nacre-like bionanocomposite films from the self-assembly of chitosan-montmorillonite hybrid building blocks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 10127–10131 (2010).

Munch, E. et al. Tough, Bio-inspired hybrid materials. Science 322, 1516–1520 (2008).

Bonderer, L. J., Studart, A. R. & Gauckler, L. J. Bioinspired design and assembly of platelet reinforced polymer films. Science 319, 1069–1073 (2008).

Deville, S., Saiz, E., Nalla, R. K. & Tomsia, A. P. Freezing as a path to build complex composites. Science 311, 515–518 (2006).

Wegst, U. G., Schecter, M., Donius, A. E. & Hunger, P. M. Biomaterials by freeze casting. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 368, 2099–2121 (2010).

Meghri, N. W. et al. Directionally solidified biopolymer scaffolds: mechanical properties and endothelial cell responses. JOM 62, 71–75 (2010).

Geim, K. Graphene: Status and prospects. Science 324, 1530–1534 (2009).

Allen, M. J., Tung, V. C. & Kaner, R. B. Honeycomb carbon: A review of graphene. Chem. Rev. 110, 132–145 (2010).

Cai, J. M. et al. Atomically precise bottom-up fabrication of graphene nanoribbons. Nature 466, 470–473 (2010).

Diez-Perez, I. et al. Gate-controlled electron transport in coronenes as a bottom-up approach towards graphene transistors. Nat. Commun. 1, 31 (2010).

Pisula, W., Feng, X. L. & Müllen, K. Charge-carrier transporting graphene-type molecules. Chem. Mater. 23, 554–567 (2011).

Wan, X. J., Long, G. K., Huang, L. & Chen, Y. S. Graphene-a promising material for organic photovoltaic cells. Adv. Mater. 23, 5342–5358 (2011).

Stankovich, S. et al. Graphene-based composite materials. Nature 442, 282–286 (2006).

Compton, O. C. & Nguyen, S. T. Graphene oxide, highly reduced graphene oxide and graphene: versatile building blocks for carbon-based materials. Small 6, 711–723 (2010).

Huang, X., Qi, X. Y., Boey, F. & Zhang, H. Graphene-based composites. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 666–686 (2012).

Bai, H., Li, C. & Shi, G. Q. Functional composite materials based on chemically converted graphene. Adv. Mater. 23, 1089–1115 (2011).

Park, S. J. & Ruoff, R. S. Chemical methods for the production of graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 217–224 (2009).

Dreyer, D. R., Park, S., Bielawski, C. W. & Ruoff, R. S. The chemistry of graphene oxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 228–240 (2010).

Wilms, D., Stiriba, S. E. & Frey, H. Hyperbranched polyglycerols: from the controlled synthesis of biocompatible polyether polyols to multipurpose applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 43, 129–141 (2010).

Hu, X. Z., Zhou, L. & Gao, C. Hyperbranched polymers meet colloid nanocrystals: a promising avenue to multifunctional, robust nanohybrids. Colloid. Polym. Sci. 289, 1299–1320 (2011).

He, H. K. & Gao, C. General approach to individually dispersed, highly soluble and conductive graphene nanosheets functionalized by nitrene chemistry. Chem. Mater. 22, 5054–5064 (2010).

Xu, Z. & Gao, C. Aqueous liquid crystals of graphene oxide. ACS Nano 5, 2908–2915 (2011).

Chen, H. Q., Müller, M. B., Gilmore, K. J., Wallace, G. G. & Li, D. Mechanically strong, electrically conductive and biocompatible graphene paper. Adv. Mater. 20, 3557–3561 (2008).

Dikin, D. A. et al. Preparation and characterization of graphene oxide paper. Nature 448, 457–460 (2007).

Park, S. J. et al. Graphene oxide papers modified by divalent ions-enhancing mechanical properties via chemical cross-linking. ACS Nano 2, 572–578 (2008).

Wang, X. L., Bai, H., Yao, Z. Y., Liu, A. R. & Shi, G. Q. Electrically conductive and mechanically strong biomimetic chitosan/reduced graphene oxide composite films. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 9032–9036 (2010).

Vigolo, B. et al. Macroscopic fibers and ribbons of oriented carbon nanotubes. Science 290, 1331–1334 (2000).

Davis, V. A. et al. True solutions of single-walled carbon nanotubes for assembly into macroscopic materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 830–834 (2009).

Behabtua, N., Green, M. J. & Pasquali, M. Carbon nanotube-based neat fibers. Nano Today 3, 24–34 (2008).

Jiang, T. et al. Processing and characterization of thermally cross-linkable poly[p-phenyleneterephthalamide-co-p-1,2-dihydrocyclobuta-phenyleneterephthalamide] (PPTA-co-XTA) copolymer fibers. Macromolecules 28, 3301–3312 (1996).

Tuzlakoglu, K., Alves, C. M., Mano, J. F. & Reis, R. L. Production and characterization of chitosan fibers and 3-D fiber mesh scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Macromol. Biosci. 4, 811–819 (2004).

Pomfret, S. J., Adams, P. N., Comfort, N. P. & Monkman, A. P. Electrical and mechanical properties of polyaniline fibres produced by a one-step wet spinning process. Polymer 41, 2265–2269 (2000).

Putz, K. W., Compton, O. C., Palmeri, M. J., Nguyen, S. B. T. & Brinson, L. C. High-nanofiller-content graphene oxide-polymer nanocomposites via vacuum-assisted self-assembly. Adv. Funct. Mater. 20, 3322–3329 (2010).

Buehler, M. J. Tu(r)ning weakness to strength. Nano Today 5, 379–383 (2010).

Sen, D. J. & Buehler, M. J. Structural hierarchies define toughness and defect-tolerance despite simple and mechanically inferior brittle building blocks. Sci. Rep. 1, 35 (2011).

Nikolov, S. et al. Revealing the design principles of high-performance biological composites using Ab initio and multiscale simulations: the example of lobster cuticle. Adv. Mater. 22, 519–526 (2010).

Compton, O. C. et al. Tuning the mechanical properties of graphene oxide paper and its associated polymer nanocomposites by controlling cooperative intersheet hydrogen bonding. ACS Nano 6, 2008–2019 (2012).

Medhekar, N. V., Ramasubramaniam, A., Ruoff, R. S. & Shenoy, V. B. Hydrogen bond networks in graphene oxide composite paper: structure and mechanical properties. ACS Nano 4, 2300–2306 (2010).

Meyers, M. A., Lin, A. Y., Chen, P. Y. & Muyco, J. Mechanical strength of abalone nacre: role of the soft organic layer. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 1, 76–85 (2008).

Checa, A. G., Cartwright, J. H. & Willinger, M. G. Mineral bridges in nacre. J. Struct. Biol. 176, 330–339 (2011).

Park, S. J., Dikin, D. A., Nguyen, S. B. T. & Ruoff, R. S. Graphene oxide sheets chemically cross-linked by polyallylamine. J. Phys. Chem. C. 113, 15801–15804 (2009).

Xu, Z. & Gao, C. Graphene chiral liquid crystals and macroscopic assembled fibres. Nat. Commun. 2, 571 (2011).

Vallés, C., Núñez, J. D., Benito, A. M. & Maser, W. K. Flexible conductive graphene paper obtained by direct and gentle annealing of graphene oxide paper. Carbon 50, 835–844 (2012).

Kan, L. Y., Xu, Z. & Gao, C. General avenue to individually dispersed graphene oxide-based two-dimensional molecular brushes by free radical polymerization. Macromolecules 44, 444–452 (2011).

Aida, T., Meijer, E. W. & Stupp, S. I. Functional supramolecular polymers. Science 335, 813–817 (2012).

Zheng, B., Wang, F., Dong, S. Y. & Huang, F. H. Supramolecular polymers constructed by crown ether-based molecular recognition. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 1621–1636 (2012).

Xu, Z. & Gao, C. In situ polymerization approach to graphene-reinforced nylon-6 composites. Macromolecules 43, 6716–6723 (2010).

Yang, M. et al. Dispersions of aramid nanofibers: a new nanoscale building block. ACS Nano 5, 6945–6954 (2011).

Xu, J. J., Wang, K., Zu, S. Z., Han, B. H. & Wei, Z. X. Hierarchical nanocomposites of polyaniline nanowire arrays on graphene oxide sheets with synergistic effect for energy storage. ACS Nano 4, 5019–5026 (2010).

Zhou, L., Gao, C., Hu, X. Z. & Xu, W. J. General avenue to multifunctional aqueous nanocrystals stabilized by hyperbranched polyglycerol. Chem. Mater. 23, 1461–1470 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. J. Lin for the molecular simulation of HPG and Dr. J. L. Sun for high resolution AFM measurements. This work is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 20974093 and No. 51173162), Qianjiang Talent Foundation of Zhejiang Province (No. 2010R10021), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2011QNA4029), Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (No. 20100101110049) and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. R4110175).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.G. conceived the concept, X.Z.H. and C.G. designed the research, analyzed the experimental data and prepared the manuscript, Z.X. joined discussion of data, gave some useful suggestions and made some artwork; X.Z.H. conducted the experiments; C.G. supervised and directed the project; all the authors read and revised the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary informations

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, X., Xu, Z. & Gao, C. Multifunctional, supramolecular, continuous artificial nacre fibres. Sci Rep 2, 767 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00767

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00767

This article is cited by

-

Advances in materials and structures of supercapacitors

Ionics (2022)

-

Carbon-based Multi-layered Films for Electronic Application: A Review

Journal of Electronic Materials (2021)

-

Nacre-inspired composites with different macroscopic dimensions: strategies for improved mechanical performance and applications

NPG Asia Materials (2018)

-

A Mini Review on Nanocarbon-Based 1D Macroscopic Fibers: Assembly Strategies and Mechanical Properties

Nano-Micro Letters (2017)

-

Multifunctional non-woven fabrics of interfused graphene fibres

Nature Communications (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.