Abstract

Non-local spin injection in lateral spin valves generates a pure spin current which is a diffusive flow of spins (i.e. spin angular momentums) with no net charge flow. The diffusive spins lose phase coherency in precession while undergoing frequent collisions and these events lead to a broad distribution of the dwell time in a transport channel between the injector and the detector. Here we show the lateral spin-valves with dual injectors enable us to detect a genuine in-plane precession signal from the Hanle effect, demonstrating the phase coherency in the in-plane precession is improved with an increase of the channel length. The coherency in the spin precession shows a universal behavior as a function of the normalized separation between the injector and the detector in material-independent fashion for metals and semiconductors including graphene.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diffusion is a transport process driven by gradients in the concentration of particles in random motion with undergoing collisions such as molecules in water, disorder in crystals and electrons and holes in a semiconductor1. Recent advance in nano-scale fabrication technology has opened up a possibility for studying such a diffusive transport of accumulated spins in a nonmagnet by means of nonlocal spin injection2,3,4,5. The mean free path for consecutive spin flip events is called “spin diffusion length” and is much longer than that of electrons' collision6. Therefore, the diffusive transport of spins, i.e., the pure spin current, provides not only a variety of scientific interests but also an additional data transfer functionality for future spintronic device applications7,8.

Hanle effect measurement is one of the most effective methods to characterize dynamic properties of the pure spin current9,10. When the magnetic field is applied perpendicular to the spin orientation, a collective spin precession is induced by its torque. In ballistic spin transport, spins can coherently rotate at a frequency proportional to the applied magnetic field. This allows us to control the direction of the spins in the channel and to manipulate the output signal of lateral spin valves (LSVs) by adjusting an effective external parameter such as the Rashba field tunable via a gate voltage11. This scheme realizes an active spin device such as the spin-transistor12. However, in a diffusive pure spin current in nonmagnets, the distributed transit times for individual spins cause the dephasing in the spin precession and decreases drastically the spin accumulation in the Hanle effect measurment13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. In this study, we employ dual spin injectors for LSVs to study coherency in the collective precession of the diffusive spins, which enhance the spin accumulation in the channel and also suppress the out of plane contribution to the Hanle effect signals due to the magnetization process of the ferromagnetic electrodes. Thereby we can detect a genuine in-plane precession signal in a 10 μm-long Ag wire which is much longer than its spin diffusion length. The coherent characteristics are investigated by the spin precession signal, revealing that the dwell time distribution narrows as the spins diffuse longer distance in the channel between the injector and the detector of LSVs.

Results

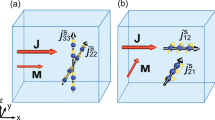

Enhanced spin accumulation in lateral spin valves with dual injectors

A conventional LSV consists of a pair of injector and detector ferromagnetic wires which are bridged by a nonmagnetic wire. The spins are injected by applying a bias voltage across the ferromagnetic/nonmagnetic interface and accumulate in its vicinity. Their density decays exponentially with a factor of exp(-d/λs) where d is the distance from the injector and λs is the spin diffusion length. Unlike the above LSV, our structure shown in Fig. 1a consists of three Fe20Ni80 (Permalloy) wires bridged by a Ag wire. The current I is applied between FM1 and FM2 for the spin injection into the Ag wire and the spin accumulation is detected in voltage V by using FM3. To avoid the spin absorption by FM wires, we use the Permalloy/MgO/Ag junction in the present study22,23. For comparison between conventional and our schemes, we depict the spatial variation of spin accumulation δμAg in the Ag wire calculated by using the same material parameters in Fig. 1b-d. In a conventional scheme of Fig. 1b, the spin injection generates the spin current IS towards both directions along the Ag wire, the magnitude of which is proportional to the spatial gradient of δμAg. On the other hand, our scheme shown in Fig. 1c and d, confines the spin current solely to the detector since the unnecessary side edge, i.e., relaxation volume, on the left of FM1 is removed. Figure 1c shows δμAg from each injector with parallel magnetization configuration and the magnitude of each spin current from FM1 and FM2 can be twice as much as the conventional IS due to the confinement effect. As the direction of spin current across the FM1/MgO/Ag and FM2/MgO/Ag interfaces is opposite each other, the currents flowing across the interfaces thus cancel out for the parallel magnetic configuration of dual injectors, whereas for the anti-parallel configuration, the spin currents induced by FM1 and FM2 are constructive as depicted in Fig.1d. As a result, this scheme can enhance the total spin current by up to a factor of four compared to the conventional one.

Sample structure and spatial variation of spin accumulation.

(a) Schematic diagram of lateral spin valve with dual injectors in non-local measurement configuration. The Permalloy wires are 140 nm in width and 20 nm in thickness. The Ag wire is 120 nm in width and 100 nm in thickness. Center-to-center separation between FM1 and FM2 d12 is 350 nm. (b) Schematic diagram of LSV with single injector and the spatial variation of spin accumulation δμ for Ag. Arrows in Ag and FM respectively represent the non-equilibrium magnetization of Ag and the magnetization of FM. The spin current IS = I↑−I↓ flows in both directions along the Ag wire. The magnitude of IS is proportional to the spatial gradient of δμAg. (c), (d) Schematic diagram of LSV with dual injectors with parallel or anti-parallel configuration and the spatial variation of spin accumulation δμ for Ag. The red and blue lines respectively show δμAg induced by spin injectors of FM1 and FM2. In parallel configuration, the flow direction of spin current from FM2 IS2 is opposite to that of FM1 IS1. In anti-parallel configuration, the flow direction of IS1 is the same as that of IS2.

The non-local spin valve signal in LSVs is shown in Fig. 2. For the conventional single injector LSV (SLSV), the high and low signals correspond respectively to the parallel and antiparallel configurations of the injector and detector FMs, of which overall change ΔRS amounts to 31.5 mΩ at 10 K in Fig. 2a. Figure 2b shows the spin signal for the dual injector LSV (DLSV). All FMs exhibit distinct switching fields at around 10 mT, 40 mT and 50 mT, corresponding to the switching fields of FM1, FM2 and FM3, respectively. The hysteresis loop shows three-level signals associated with the following magnetic configurations; in the negative sweep (green line), the magnetization of FM1 flips at −10 mT and the injectors' magnetization configuration becomes antiparallel. Accordingly FM3 detects the change in the electrochemical potential and the resulting change in δμAg is shown in Fig. 1d. Further decrease in field down to −40 mT flips the magnetization of FM2 and returns the injectors' magnetic configuration to parallel. Since the antiparallel configuration maximizes the spin accumulation in DLSV, it can be evaluated from the overall change ΔRS between the minor loop shown in a red curve and the positive sweep shown in a blue line in Fig. 2b. The center-to-center injector and detector separation L dependence of ΔRS in Fig. 2c shows that ΔRS of DLSV is almost 3 times larger than that of SLSV and decreases exponentially with increasing L due to Elliot-Yafet spin relaxation mechanism in the Ag wire24,25.

Non-local spin signals.

(a) Spin signal as a function of y-directional magnetic field for SLSV at 10 K. The arrows indicate the magnetization configuration of two Permalloy wires. The triangles indicate the sweep direction of the magnetic field. (b) Spin signal as a function of magnetic field for DLSV at 10 K. The arrows indicate the magnetization configuration of three Permalloy wires. The triangles indicate the sweep direction of the magnetic field. The red line shows the minor hysteresis loop. (c) Spin valve signal ΔRS as a function of injector-detector separation at T = 10 K. The solid lines are the fitting curves using equation (1) with the same fitting parameters for SLSV and DLSV.

The analytical expression of ΔRS for DLSV, for the case where the interface resistance is enough higher than the spin resistance of the nonmagnetic wire RN, is approximated by using a solution of one-dimensional spin diffusion equation (see Supplementary Information for details)

where  is the enhancement factor, PI is interfacial polarization, λN is the spin diffusion length of the nonmagnet and d12 is the separation between FM1 and FM2. The ΔRS for DLSV is remarkably enhanced by a factor of α compared to that of SLSV, corresponding to the reduced equation (1) of ΔRS for SLSV26 with d12 ≫ λΝ. The first and second terms in α represent the spin current injected from FM2 and the third term does the spin current injected from FM1. The obtained experimental results in Fig. 2c were fitted to equation (1) with adjusting parameters PI and λN, yielding PI = 0.36, λN = 1500 nm and α = 3.2. Note that the obtained valves of PI and λN are consistent with our previous data for SLSV with Permalloy/MgO/Ag junctions22 and α is decreased due to the spin relaxation in the channel between the two injectors.

is the enhancement factor, PI is interfacial polarization, λN is the spin diffusion length of the nonmagnet and d12 is the separation between FM1 and FM2. The ΔRS for DLSV is remarkably enhanced by a factor of α compared to that of SLSV, corresponding to the reduced equation (1) of ΔRS for SLSV26 with d12 ≫ λΝ. The first and second terms in α represent the spin current injected from FM2 and the third term does the spin current injected from FM1. The obtained experimental results in Fig. 2c were fitted to equation (1) with adjusting parameters PI and λN, yielding PI = 0.36, λN = 1500 nm and α = 3.2. Note that the obtained valves of PI and λN are consistent with our previous data for SLSV with Permalloy/MgO/Ag junctions22 and α is decreased due to the spin relaxation in the channel between the two injectors.

Experimental observation of genuine spin precession signal

The Hanle effect measurements were performed on LSVs by applying perpendicular magnetic fields. Figure 3a shows the modulated non-local spin signal for SLSV and DLSV. A parabolic background signal is observed for the SLSV, the origin of which is the magnetization process of FMs. When the applied magnetic field is increased above the demagnetizing field of the FM wires, the magnetizations for the injector and the detector are tilted up along the field direction, pushing the background signal up towards the value of parallel configuration for FMs. To describe the both contributions of spin precession and magnetization process, we decompose them into that of spin precession in x-y plane and that of the z component reflecting the magnetization process. The non-local spin signal V/I in the presence of BZ is thus given by the sum of the above two contributions;

with

where  ,

,  τsf = λN2/DN the spin relaxation time, DN the diffusion constant, ωL = γeBz the Larmor frequency,

τsf = λN2/DN the spin relaxation time, DN the diffusion constant, ωL = γeBz the Larmor frequency,  the gyromagnetic ratio, g the g-factor, μB the Bohr magneton and aFMi is the projection of the unit vector of the magnetization of FMi eFMi on y or z-axis. Note here that

the gyromagnetic ratio, g the g-factor, μB the Bohr magneton and aFMi is the projection of the unit vector of the magnetization of FMi eFMi on y or z-axis. Note here that  represents the nonlocal resistance at the precessional frequency ωL and

represents the nonlocal resistance at the precessional frequency ωL and  does that without spin precession (see Supplementary Information for details). For SLSV, we obtain PI = 0.37 and λN = 1420 nm by fitting equation (2) to the experimental data as shown in Fig. 3a, which are consistent with those obtained alternatively from the L dependence of ΔRS in the previous section. For DLSV, the z component of the injectors is canceled out because of the opposite direction of the applied current to the junctions as depicted in Fig. 3b. This allows us to detect the genuine precession signal in Fig. 3a.

does that without spin precession (see Supplementary Information for details). For SLSV, we obtain PI = 0.37 and λN = 1420 nm by fitting equation (2) to the experimental data as shown in Fig. 3a, which are consistent with those obtained alternatively from the L dependence of ΔRS in the previous section. For DLSV, the z component of the injectors is canceled out because of the opposite direction of the applied current to the junctions as depicted in Fig. 3b. This allows us to detect the genuine precession signal in Fig. 3a.

Spin precession measurements by using Hanle effect.

(a) Non-local spin signal modulated by spin precession as a function of perpendicular field for single and dual injector LSVs with L = 6 μm at 10 K. The solid lines are the fitting curves using equation (2). (b) Schematic diagram of magnetizations of injectors and non-equilibrium magnetization m in the Ag wire in the presence of high BZ. In Ag, y-components of m1 and m2 are constructive but z-component of them are canceled each other out both for anti-parallel and parallel magnetization configurations of the injectors. (c) Coherent parameter of the spin precession  as a function of L. The solid lines are the fitting curves using equation (2) with the same parameters as used in (a). Data are corrected by taking account of the influence of magnetization process. (d)–(f), Density of y-directional spin arrived at the detector as a function of dwell time for LSVs with different L. The black and red lines, respectively, represent the distribution of the dwell time in the channel without and with BZ that causes π rotation after spins are injected.

as a function of L. The solid lines are the fitting curves using equation (2) with the same parameters as used in (a). Data are corrected by taking account of the influence of magnetization process. (d)–(f), Density of y-directional spin arrived at the detector as a function of dwell time for LSVs with different L. The black and red lines, respectively, represent the distribution of the dwell time in the channel without and with BZ that causes π rotation after spins are injected.

Towards coherent spin precession

In the diffusive pure-spin transport, the collective spin precession decoheres due to broadening of the dwell time distribution in the channel between the injector and the detector10. The amplitude of the spin valve signal at BZ = 0 decreases after the π rotation at  = 0.16 T, as can be seen in Fig. 3a. In order to better quantify the coherency in the collective spin precession, we define the figure of merit as the ratio

= 0.16 T, as can be seen in Fig. 3a. In order to better quantify the coherency in the collective spin precession, we define the figure of merit as the ratio  , where

, where  and

and  are respectively the amplitude of the spin valve signal right after the π rotation and that in zero field right before the rotation begins. The

are respectively the amplitude of the spin valve signal right after the π rotation and that in zero field right before the rotation begins. The  increases with increasing L and the experimental trend is well reproduced by equation (2) as shown in Fig. 3c. To understand the observed trend in more detail, we employ the one-dimensional diffusion model which gives the y-component of net spin density at the detector <Sy>

increases with increasing L and the experimental trend is well reproduced by equation (2) as shown in Fig. 3c. To understand the observed trend in more detail, we employ the one-dimensional diffusion model which gives the y-component of net spin density at the detector <Sy>  , as a function of the dwell time t in the presence of BZ10. The <Sy> versus t curves for L = λN with BZ = 0 and

, as a function of the dwell time t in the presence of BZ10. The <Sy> versus t curves for L = λN with BZ = 0 and  are shown in Fig. 3d. When BZ = 0, <Sy> takes a broad peak structure followed by a long exponential tail. The detected spin signal in LSVs is proportional to the <Sy> integrated over time. The distribution of

are shown in Fig. 3d. When BZ = 0, <Sy> takes a broad peak structure followed by a long exponential tail. The detected spin signal in LSVs is proportional to the <Sy> integrated over time. The distribution of  gets narrower as the channel length becomes longer, of which evolution is depicted in three distribution curves under BZ = 0 of Figs. 3d–f. The long exponential tail observed in Fig. 3d diminishes in proportion to

gets narrower as the channel length becomes longer, of which evolution is depicted in three distribution curves under BZ = 0 of Figs. 3d–f. The long exponential tail observed in Fig. 3d diminishes in proportion to  . When

. When  is applied, the integrated value of <Sy> over time cancel for short separation L ~ λN (Fig. 3d) whereas it does not cancel for long separation L ≫ λN (Figs. 3e and f), indicating that the coherence of collective spin precession is well preserved for long spin transport. This trend is experimentally observed as an increase of

is applied, the integrated value of <Sy> over time cancel for short separation L ~ λN (Fig. 3d) whereas it does not cancel for long separation L ≫ λN (Figs. 3e and f), indicating that the coherence of collective spin precession is well preserved for long spin transport. This trend is experimentally observed as an increase of  from 0.21 to 0.53 with L as shown in Fig. 3c. In spin-polarized electron transport, a drift field is utilized to suppress the distributed transit time of the spins and almost coherent spin precession with

from 0.21 to 0.53 with L as shown in Fig. 3c. In spin-polarized electron transport, a drift field is utilized to suppress the distributed transit time of the spins and almost coherent spin precession with  ~ 1 is reported for a 350 μm-thick undoped single-crystal Si wafer27.

~ 1 is reported for a 350 μm-thick undoped single-crystal Si wafer27.

Discussion

To better understand the coherence in collective spin precession for the pure-spin current,  is substituted into the distribution function at BZ = 0. We then obtain

is substituted into the distribution function at BZ = 0. We then obtain  , where T is dimensionless time. This implies that the distribution of the dwell time, i.e., coherency, is characterized only by L/λN and more importantly it does not depend on the kind of materials as long as their transport is diffusive. To check this idea the L/λN dependence of

, where T is dimensionless time. This implies that the distribution of the dwell time, i.e., coherency, is characterized only by L/λN and more importantly it does not depend on the kind of materials as long as their transport is diffusive. To check this idea the L/λN dependence of  are summarized by using the data so far reported for metals, semiconductors and graphene in Fig. 4. Interestingly the relation between the coherence and the normalized separation shows a universal behavior and the experimental data are well reproduced by equation (2). We shall note here that the effective length L/λN, not the spin lifetime, is an important parameter to manipulate the spin precession coherently in the diffusive pure-spin transport while the spin accumulation is relaxed during the diffusive transport in the channel. Therefore, the high spin injection efficiency of the Permalloy/MgO/Ag junction and the confinement effect in the DLSV structure could offer advantages for realizing giant spin accumulation as well as coherent spin precession along a 10 μm-long Ag wire which is much longer than the spin diffusion length.

are summarized by using the data so far reported for metals, semiconductors and graphene in Fig. 4. Interestingly the relation between the coherence and the normalized separation shows a universal behavior and the experimental data are well reproduced by equation (2). We shall note here that the effective length L/λN, not the spin lifetime, is an important parameter to manipulate the spin precession coherently in the diffusive pure-spin transport while the spin accumulation is relaxed during the diffusive transport in the channel. Therefore, the high spin injection efficiency of the Permalloy/MgO/Ag junction and the confinement effect in the DLSV structure could offer advantages for realizing giant spin accumulation as well as coherent spin precession along a 10 μm-long Ag wire which is much longer than the spin diffusion length.

Coherency of spin precession in diffusive pure-spin current.

Coherent parameter of the spin precession  as a function of L/λN. The solid line is a universal curve obtained from equation (2).

as a function of L/λN. The solid line is a universal curve obtained from equation (2).

For spintronic devices using such a long-diffusion spin current, fast spin transport may be critical. The high coherence of the spin precession over  = 0.4 is reported for Al and graphene as can be seen in Fig. 4, however, the diffusion constant of the pure spin current is 0.003 m2/s and 0.01 m2/s13,20, respectively, which is much slower than that of Ag (0.047 m2/s). Therefore, the experimental results in this study could be useful in developing a new class of spintronic devices and the material-independent perspective for the spin precession will be beneficial for us to design pure-spin-current-based memory and logic devices by using a variety of metallic and semi-conductive materials including graphene.

= 0.4 is reported for Al and graphene as can be seen in Fig. 4, however, the diffusion constant of the pure spin current is 0.003 m2/s and 0.01 m2/s13,20, respectively, which is much slower than that of Ag (0.047 m2/s). Therefore, the experimental results in this study could be useful in developing a new class of spintronic devices and the material-independent perspective for the spin precession will be beneficial for us to design pure-spin-current-based memory and logic devices by using a variety of metallic and semi-conductive materials including graphene.

Methods

Lateral spin valves with Permalloy/MgO/Ag junctions are prepared on a Si/SiO2 substrate by means of shadow evaporation using a suspended resist mask which is patterned by e-beam lithography. All the layers are e-beam deposited in an ultra-high vacuum condition of about 10−6 Pa. First, 20-nm-thick Permalloy layer is obliquely deposited at a tilting angle of 45° from substrate normal. Second, the interface MgO layer is deposited at the same tilting angle of 45°. Third, 100-nm-thick Ag layer is deposited normal to the Si substrate. Finally, 3-nm-thick capping MgO layer is deposited to prevent surface contamination of the devices. After the liftoff process, the devices are annealed at 400°C for 40 min in an N2 (97%) + H2 (3%) atmosphere28.

The non-local measurements are carried out by a dc current source and nano-voltmeter. The bias current in the range between 200 and 400 μA is applied to the injector. The magnetic field is applied parallel to the Permalloy wires for the spin valve measurements. The switching field of Permalloy wires is controlled not only by changing the width but also by attaching a large domain wall reservoir at the edge. For the Hanle effect measurements, the magnetic field is applied perpendicular to the Si substrate. The field direction is carefully controlled to rule out the misalignment that causes the in-plane field component that switches the magnetization of Permalloy in the plane during the measurements.

References

Jost, W. Diffusion in solids, liquids, gases (Academic Press, 1960).

Johnson, M. & Silsbee, R. H. Interfacial charge-spin coupling: injection and detection of spin magnetization in metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 1790–1793 (1985).

Johnson, M. & Silsbee, R. H. Thermodynamic analysis of interfacial transport and of the thermomagnetoelectric system. Phys. Rev. B 35, 4959–4972 (1987).

Van Son, P. C., van Kempen, H. & Wyder, P. Boundary resistance of ferromagnetic-nonferromagnetic metal interface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 2271–2273 (1987).

Jedema, F. J., Filip, A. T. & van Wees, B. J. Electrical spin injection and accumulation at room temperature in an all-metal mesoscopic spin valve. Nature 410, 345–348 (2001).

Bass, J. & Pratt Jr, W. P. Spin-diffusion lengths in metals and alloys and spin-flipping at metal/metal interfaces: an experimentalist's critical review. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 19, 183201 (2007).

Žutić, I., Fabian, J., & Sarma, S. D. Spintronics: fundamentals and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 76, 323–410 (2004).

Chappert, C., Fert, A. & Van Dau, F. N. The emergence of spin electronics in data storage. Nature Mater. 6, 813–823 (2007).

Johnson, M. & Silsbee, R. H. Coupling of electronic charge and spin at a ferromagnetic-paramagnetic metal interface. Phys. Rev. B 37, 5312–5325 (1988).

Jedema, F. J., Heershe, H. B., Filip, A. T., Baselmans, J. J. A. & van Wees, B. J. Electrical detection of spin precession in a metallic mesoscopic spin valve. Nature 416, 713–716 (2002).

Bychkov, Y. A. & Rashba, E. I. "Oscillatory effects and the magnetic susceptibility of carriers in inversion layers." J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 17, 6039 (1984).

Datta, S. & Das, B. Electronic analog of the electro-optic modulator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 56, 665–667 (1990).

Valenzuela, S. O. & Tinkham, M. Direct electronic measurement of the spin Hall effect. Nature 442, 176–179 (2006).

Van Staa, A., Wulfhorst, J., Vogel, A., Merkt, U. & Meier, G. Spin precession in lateral all-metal spin valves: Experimental observation and theoretical description. Phys. Rev. B 77, 214416 (2008).

Lou, X. et al. Electrical detection of spin transport in lateral ferromagnet-semiconductor devices. Nature Phys. 3, 197–202 (2007).

Vant Erve, O. M. J. et al. Information Processing With Pure Spin Currents in Silicon: Spin Injection, Extraction, Manipulation and Detection. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 56, 2343–2347 (2009).

Sasaki, T. et al. Temperatrue dependence of spin diffusion length in silicon by Hanle-type spin precession. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 122101 (2010).

Tombros, N., Józsa, C., Popinciuc, M., Jonkman, H. T. & Van Wees, B. J. Electronic spin transport and spin precession in single graphene layers at room temperature. Nature 448, 571–574 (2007).

Popinciuc, M. et al. Electronic spin transport in graphene field-effect transistors. Phys. Rev. B 80, 214427 (2009).

Maassen, T., Dejene, F. K., Guimarães, M. H., Józsa, C. & Van Wees, B. J. Comparison between charge and spin transport in few-layer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 83, 115410 (2011).

Han, W. et al. Tunneling spin injection into single layer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 167202 (2010).

Fukuma, Y. et al. Giant enhancement of spin accumulation and long-distance spin precession in metallic lateral spin valves. Nature Mater. 10, 527–531 (2011).

Fukuma, Y., Wang, L., Idzuchi, H. & Otani, Y. Enhanced spin accumulation obtained by inserting low-resistance MgO interface in metallic lateral spin valves. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 012507 (2010).

Elliott, R. J. Theory of the effect of spin-orbit coupling on magnetic resonance in some semiconductors. Phys. Rev. 96, 266–279 (1954).

Yafet, Y. g Factors and Spin-Lattice Relaxation of Conduction Electrons: Solid State Physics. pp. 1–98 (Academic, New York., 1963).

Takahashi, S. & Maekawa, S. Spin injection and detection in magnetic nanostructures. Phys. Rev. B 67, 052409 (2003).

Huang, B., Monsma, D. J. & Appelbaum, I. Coherent spin transport through a 350 micron thick silicon wafer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 177209 (2007).

Wang, L. et al. Effect of annealing on interfacial spin polarization and resistance in Permalloy/MgO/Ag lateral spin valves. Appl. Phys. Express. 4, 093004 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work is partly supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) (No. 23244071) and Young Science Aid (A) (No. 23681032) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H. I. and Y. F. designed the experiments, fabricated devices and performed analysis. Y. O. supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Nonlocal resistance in a lateral spin valve with dual injectors

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Idzuchi, H., Fukuma, Y. & Otani, Y. Towards coherent spin precession in pure-spin current. Sci Rep 2, 628 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00628

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00628

This article is cited by

-

Enhanced Tunnel Spin Injection into Graphene using Chemical Vapor Deposited Hexagonal Boron Nitride

Scientific Reports (2014)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.