Abstract

Phase transitions are usually treated as equilibrium phenomena, which yields telltale universality classes with scaling behavior of relaxation time and healing length. However, in second-order phase transitions relaxation time diverges near the critical point (“critical slowing down”). Therefore, every such transition traversed at a finite rate is a non-equilibrium process. Kibble-Zurek mechanism (KZM) captures this basic physics, predicting sizes of domains – fragments of broken symmetry – and the density of topological defects, long-lived relics of symmetry breaking that can survive long after the transition. To test KZM we simulate Bose-Einstein condensation in a ring using stochastic Gross-Pitaevskii equation and show that BEC formation can spontaneously generate quantized circulation of the newborn condensate. The magnitude of the resulting winding numbers and the time-lag of BEC density growth – both experimentally measurable – follow scalings predicted by KZM. Our results may also facilitate measuring the dynamical critical exponent for the BEC transition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Second order phase transitions are always associated with divergence of both the relaxation time (“critical slowing down”) and healing length (“critical opalescence”) at the critical point. These divergences imply inevitable non-adiabaticity when a system is driven across the transition and result in a finite size of domains that can coordinate symmetry breaking. That size is set by the healing length at the time when the system can no longer keep up with the externally imposed change of parameters that drive it through the transition and adiabatic following gives way to impulse “freezeout” of its state.

This mosaic of domains with independent choices of broken symmetry may result in topological defects. Their densities at formation will bear universal signatures of the underlying phase transition. Kibble-Zurek mechanism (KZM) is the theoretical framework that describes the dynamics of symmetry breaking in second order phase transitions by taking into account finite speed of propagation of the relevant information1,2,3,4,5. KZM leads to a quantitative estimate for the density of defects3,4,5,6. In particular, it predicts that their density should scale with the quench rate. The scaling exponent predicted by KZM is a function of the critical exponents of the underlying equilibrium phase transition. The basic ingredients for this prediction are the critical exponents – i.e., the universality class of the transition. Therefore, applicability of KZM spans physical phenomena of enormous variety and scales, starting from microscopic phenomenon of vortex formation in superfluid, right up to phenomena of astronomical scales, like formation of structures (cosmic strings, monopoles, etc.) in the early Universe.

Kibble-Zurek mechanism has been tested in a number of primarily numerical studies, see, e.g., Refs. 7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. However, on the experimental side, while, as of now, data confirm key qualitative predictions of KZM (creation of topological excitations)15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25, its key quantitative prediction (scaling of their density with the rate of quench) has not yet been convincingly demonstrated (see, however, Refs. 23,24,25, for suggestive indirect evidence). The difficulty involves controlling sufficient range of quench time scales as well as counting defects.

In this article we pave a way around this long-standing hindrance. Within the setup of Bose-Einstein condensation transition in an effectively one-dimensional ring, we demonstrate that KZM scaling laws can be observed involving stable and experimentally accessible quantities, namely, the variance of the winding number W and the non-adiabatic response time for density growth. Looking for signature of KZM in growth of bulk density is a novel perspective which allows bypassing the traditional difficulty of counting and resolving defects. Our demonstration is also a long overdue numerical verification of the original prediction proposed within the setup of superfluid circulation in an annulus3.

Manifestations of symmetry breaking associated with BEC formation are spectacular and diverse6,7,8,9,10,12,13,15,17,18,19,26. Formation of BEC breaks the U(1) symmetry of the phase of the condensate wave-function. We show that when BEC forms in a ring cooled through the critical temperature, this symmetry breaking may result in spontaneous rotation in the newborn condensate. Persistence of the resulting flow is assured by topological stability of the quantized winding number W. We show that Ws stabilize soon after the transition and the variance of their distribution follows the scaling predicted by the KZM. Density growth of BEC also exhibits behavior consistent with KZM.

Recently, persistent circulation of BEC in toroidal trap has been achieved experimentally by stirring the cloud27. In particular, with the advent of circular trapping potential for BEC28,29,30,31, the possible experimental testing of KZM is around the corner. Density growth in BEC formation with variable cooling rate has also been observed15,32. We show that a similar setup would allow both the testing of density growth scaling and determining the critical properties of the Bose-Einstein condensate3,4,5.

Results

The Model

We consider a BEC in a quasi-1D ring of circumference C, an idealization of quasi-1D toroidal geometry, e.g., see28,29,30,31,33,34. We model it using the stochastic Gross-Pitaevskii equation (SGPE)35,36,37:

where φ = |φ(x)|eiθ(x) is the condensate wavefunction and η(x, t) is the thermal noise satisfying the fluctuation-dissipation relation 〈η(x, t)η*(x′, t′)〉 = 2γTδ(x − x′)δ(t − t′), with γ representing the dissipation, T the noise amplitude,  the non-linearity parameter and

the non-linearity parameter and  the chemical potential. We use dimensionless units given by

the chemical potential. We use dimensionless units given by  , m = 1 (mass of a 87Rb atom) and unit of time = 1/ω0 with ω0 = 200 × 2π Hz. We set τ0 = γ−1+γ and

, m = 1 (mass of a 87Rb atom) and unit of time = 1/ω0 with ω0 = 200 × 2π Hz. We set τ0 = γ−1+γ and  7,8.

7,8.

Leaving aside the noise and dissipation, the above system can be described by the energy functional  , where

, where  . Extremizing the energy functional we obtain φ = 0 for

. Extremizing the energy functional we obtain φ = 0 for  and

and  for

for  , where θ is the wave function phase (

, where θ is the wave function phase ( is the critical point). We induce the transition by quenching

is the critical point). We induce the transition by quenching  :

:

from an initial  to a final

to a final  and allow the system enough time to stabilize. The critical point is crossed at t = 0. Simulation of cooling of BEC by quenching chemical potential within the framework of SGPE has been shown to reproduce experimental results on defect (vortex) generation; see, e.g. Refs. 15,35,36,37.

and allow the system enough time to stabilize. The critical point is crossed at t = 0. Simulation of cooling of BEC by quenching chemical potential within the framework of SGPE has been shown to reproduce experimental results on defect (vortex) generation; see, e.g. Refs. 15,35,36,37.

KZM in 1-D BEC Ring

When BEC is formed via cooling through the critical point, non-adiabaticity is enforced by diverging relaxation time τ and healing length ξ3,4,5:

Here ν and z are the critical exponents, ξ0 and τ0 are determined by the microscopic details of the system. According to KZM, as  approaches 0, after the instant

approaches 0, after the instant  the relaxation time

the relaxation time  exceeds the timescale

exceeds the timescale  of the change imposed by quench and the state of the system freezes. Its order parameter behaves impulsively (i.e., remains effectively frozen) within an interval between

of the change imposed by quench and the state of the system freezes. Its order parameter behaves impulsively (i.e., remains effectively frozen) within an interval between  and starts dynamical evolution again thereafter. KZM gives

and starts dynamical evolution again thereafter. KZM gives

For the linear quench in Eq. (2), we get from Eqs. (3), (4)

where  . As

. As  becomes negative, condensate starts forming with a phase profile θ(x) consisting of random patches: phase is approximately uniform over the length-scale

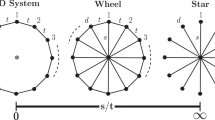

becomes negative, condensate starts forming with a phase profile θ(x) consisting of random patches: phase is approximately uniform over the length-scale  . Within each such patch, its value is chosen independently and randomly (different stages of condensate formation in a uniform ring are shown in Fig. 1 upper row). Therefore, we can estimate the variance of the total phase

. Within each such patch, its value is chosen independently and randomly (different stages of condensate formation in a uniform ring are shown in Fig. 1 upper row). Therefore, we can estimate the variance of the total phase  within a torus of circumference C by considering the sum of

within a torus of circumference C by considering the sum of  uniform random variables, each having the same variance π2/3 (θ taking any value between ±π). This implies Gaussian distribution for θc (in agreement with inset of Fig. 3a) with variance

uniform random variables, each having the same variance π2/3 (θ taking any value between ±π). This implies Gaussian distribution for θc (in agreement with inset of Fig. 3a) with variance  when averaged over many realizations. As the wave function is single-valued, we must have θc = 2πW, where W is the integer winding number. So, Eq. (5) predicts dispersion:

when averaged over many realizations. As the wave function is single-valued, we must have θc = 2πW, where W is the integer winding number. So, Eq. (5) predicts dispersion:

using the mean field exponents z = 2 and ν = 1/27,8.

Condensate Growth in the ring.

Sequences of isodensity surfaces for growing condensate for a single quench realization with τQ = 0.01 for flat ring (top line, time flowing from (a) to (c)) and tilted ring with tilting angle α = 3° (bottom line, time flowing from from (d) to (f)). Color represents the phase of the condensate along the ring, showing magnitude of W to be 1 and 2 respectively in the flat (c) and the tilted (f) rings. The 3D equivalent is constructed for a ring with isotropic harmonic transverse confinement with frequency ω0 = 200 × 2π Hz and other parameters as mentioned in the text for Figs. 2 and 3 (see “Methods” section for discussion on this equivalence). Formation of random equi-phased patches at the onset of condensation is clearly visible.

Scaling Laws.

(a) The scaling for  (averaged over > 103 realizations) with τQ for C = 30 (open circle) and 120 (filled diamonds). The error bars indicate the standard deviations. Best fits (red line) in the Fig. give exponents 0.1262 ± 0.0026 for the C = 30 and 0.126 ± 0.0075 for C = 120, compared to the expected ν/2(1 + νz) = 1/8 = 0.125 (Eq. 6). Random walk in phase prediction

(averaged over > 103 realizations) with τQ for C = 30 (open circle) and 120 (filled diamonds). The error bars indicate the standard deviations. Best fits (red line) in the Fig. give exponents 0.1262 ± 0.0026 for the C = 30 and 0.126 ± 0.0075 for C = 120, compared to the expected ν/2(1 + νz) = 1/8 = 0.125 (Eq. 6). Random walk in phase prediction  , i.e., log(〈|W|〉C = 120) – log(〈|W|〉C = 30) ~ log2 (Eq.2), is also verified (the difference shown in the Fig. is ≈ 0.308 compared to log2 ≈ 0.301). The inset shows histograms for distribution of W. (b) N vs

, i.e., log(〈|W|〉C = 120) – log(〈|W|〉C = 30) ~ log2 (Eq.2), is also verified (the difference shown in the Fig. is ≈ 0.308 compared to log2 ≈ 0.301). The inset shows histograms for distribution of W. (b) N vs  . The “knees”, where N shoots up (point A), show perfect overlap for different τQ's (values marked in the Fig.) and can be used for estimating critical exponents. All static parameters are same as in Fig. 2.

. The “knees”, where N shoots up (point A), show perfect overlap for different τQ's (values marked in the Fig.) and can be used for estimating critical exponents. All static parameters are same as in Fig. 2.

Spatial gradient of θ(x) gives local flow velocity. Therefore, W quantifies the net quantized circulation of the condensate around the ring. Thus, breaking of U(1) symmetry leads to independent phase selection and results in a net superfluid circulation in the ring3,4,5. The scaling predicted above is valid when expected |W| > 1. It steepens for 〈|W|〉 ~ 1 or smaller; see23,24,25,38,39 and references therein.

We also observe that the scaling of  in Eq. (5) can be extracted from the growth of the condensate density. It shows a sharp “knee” behavior, revealing a characteristic response time as the transition point is crossed. The response time gives an effective

in Eq. (5) can be extracted from the growth of the condensate density. It shows a sharp “knee” behavior, revealing a characteristic response time as the transition point is crossed. The response time gives an effective  , which follows the scaling in Eq. (5).

, which follows the scaling in Eq. (5).

Simulation Results for Winding Numbers

We integrate Eq. (1) numerically to study the quench dynamics. Evolution of W, BEC particle number N, total angular momentum L and specific angular momentum L/N are illustrated in Fig. 2. We define total angular momentum L through single particle angular momentum operator. Assuming our wavefunction  , the total angular momentum (only the z-component is non-zero) is given by

, the total angular momentum (only the z-component is non-zero) is given by  . Each quench in this figure continues from

. Each quench in this figure continues from  to

to  , where it is held fixed for the rest of the time. Though the flow involves more mass as

, where it is held fixed for the rest of the time. Though the flow involves more mass as  decreases, W acquires a stable value right after the symmetry-breaking. Both L and N grow as long as

decreases, W acquires a stable value right after the symmetry-breaking. Both L and N grow as long as  decreases, but L/N stabilizes to a steady value along with W. This is analogous to the build up of persistent current in superfluid He3,4,5,40. For spatially uniform density the simple relation L/N = W holds and we observe that at the tail-end of the quench (last row), when the density fluctuations are ironed out due to dissipation. Final kinetic energy of the BEC depends on the final steady value of W and scales with it quadratically. W stabilizes (first row) in the wake of the condensation, when N (second row) is still negligible. Thus, W retains phase information from soon after BEC formation at the time of symmetry breaking. Once stabilized, W is resilient to dissipation and typical ambient thermal fluctuations, due to its quantized nature. The scaling in Eq. (6) is verified by averaging |W| over > 103 realizations. Here the quenches are also between

decreases, but L/N stabilizes to a steady value along with W. This is analogous to the build up of persistent current in superfluid He3,4,5,40. For spatially uniform density the simple relation L/N = W holds and we observe that at the tail-end of the quench (last row), when the density fluctuations are ironed out due to dissipation. Final kinetic energy of the BEC depends on the final steady value of W and scales with it quadratically. W stabilizes (first row) in the wake of the condensation, when N (second row) is still negligible. Thus, W retains phase information from soon after BEC formation at the time of symmetry breaking. Once stabilized, W is resilient to dissipation and typical ambient thermal fluctuations, due to its quantized nature. The scaling in Eq. (6) is verified by averaging |W| over > 103 realizations. Here the quenches are also between  , except for the fastest one, for which it is done between

, except for the fastest one, for which it is done between  , so that the quench begins and ends outside the impulse region between

, so that the quench begins and ends outside the impulse region between  . The simulation results compare favorably with the KZM prediction, as summarized in Fig. 3(a). A direct comparison between the numerical results and KZM formula for our model (Eq. 6) yields, σ(W)(KZM) = 5.94, 4.86 and 3.65 versus σ(W) (numerical) = 2.33, 1.83 and 1.35 for τQ = 0.01, 0.05 and 0.5 respectively. With “naive” KZM (choices of phases over

. The simulation results compare favorably with the KZM prediction, as summarized in Fig. 3(a). A direct comparison between the numerical results and KZM formula for our model (Eq. 6) yields, σ(W)(KZM) = 5.94, 4.86 and 3.65 versus σ(W) (numerical) = 2.33, 1.83 and 1.35 for τQ = 0.01, 0.05 and 0.5 respectively. With “naive” KZM (choices of phases over  -sized regions are completely independent), mismatch of this order is consistent with (actually, significantly less than) past observations12,13,41. We shall comment on this further in the Discussion. The square-root dependence of 〈|W|〉 on C, Eq.(6) is also verified there, as the values of 〈|W|〉 obtained for C = 120 are approximately double of those obtained for C = 30 for the same τQs (Fig. 3a).

-sized regions are completely independent), mismatch of this order is consistent with (actually, significantly less than) past observations12,13,41. We shall comment on this further in the Discussion. The square-root dependence of 〈|W|〉 on C, Eq.(6) is also verified there, as the values of 〈|W|〉 obtained for C = 120 are approximately double of those obtained for C = 30 for the same τQs (Fig. 3a).

Quenching into a BEC and its consequences.

Time evolution of the winding number W, total number of BEC atoms N, total angular momentum L and specific angular momentum L/N for random instances of quench realizations with different τQ. The quench is induced by ramping  linearly from –500 to +500 in each case (Eq. 2). For each τQ, different quantities for the same realization are plotted in same color. The black vertical lines indicates tc = 0 (continuous, middle one) and the two on either sides (dashed) indicate

linearly from –500 to +500 in each case (Eq. 2). For each τQ, different quantities for the same realization are plotted in same color. The black vertical lines indicates tc = 0 (continuous, middle one) and the two on either sides (dashed) indicate  , where

, where  and τ0 = γ–1 + γ. The second row shows the adiabatic-impulse transition in BEC growth. While

and τ0 = γ–1 + γ. The second row shows the adiabatic-impulse transition in BEC growth. While  gives the KZM estimate for the impulse to adiabatic transition boundary, the instant denoted by A in the figure marks the point where N shoots up sharply. The thin blue lines indicate the equilibrium values of N for the corresponding instantaneous values of

gives the KZM estimate for the impulse to adiabatic transition boundary, the instant denoted by A in the figure marks the point where N shoots up sharply. The thin blue lines indicate the equilibrium values of N for the corresponding instantaneous values of  . Prior to the quench, we thermalize the system at the initial value of the chemical potential. T = 10–3, γ = 10–2 and

. Prior to the quench, we thermalize the system at the initial value of the chemical potential. T = 10–3, γ = 10–2 and  are held constant for all time.

are held constant for all time.

Thorough initial thermalization is crucial in producing equilibrated initial state (and, hence, physically motivated final state). In particular, noise should randomize the phase along the entire circumference C. Otherwise, winding numbers saturate (as we have observed with runs that did not attain this initial long-range thermalization of the phase). This randomization of the phase is in effect a diffusive process that requires time ~C2, which renders accurate reproduction of the scaling behavior for large C numerically costly.

Adiabatic-impulse transition is at the heart of the scaling laws predicted by KZM. Here we observe for the first time its manifestation in BEC formation as a scaling-law for the length of the impulse reaction time (effective  ; see, e.g. Ref. 41) for the condensate density growth (see however, similar plot for time-dependent spin alignment in spinor BEC42). This is an important result, since density evolution in a condensation process is easier to study experimentally than the phase ordering associated with defect dynamics. We compare (Fig. 2, second row) the growth of N, with the instantaneous equilibrium value of N (thin blue straight-line segments), obtained from the relation

; see, e.g. Ref. 41) for the condensate density growth (see however, similar plot for time-dependent spin alignment in spinor BEC42). This is an important result, since density evolution in a condensation process is easier to study experimentally than the phase ordering associated with defect dynamics. We compare (Fig. 2, second row) the growth of N, with the instantaneous equilibrium value of N (thin blue straight-line segments), obtained from the relation  (valid for small

(valid for small  ). Initially,

). Initially,  and N is negligible. After crossing tc the instantaneous equilibrium value of N increases linearly with the rate

and N is negligible. After crossing tc the instantaneous equilibrium value of N increases linearly with the rate  till t = 500τQ, where the ramp is stopped and equilibrium value for N settles to 3 × 105. But for the actual evolution, the length of the period from t = tc = 0 up to the point denoted by A (a sharp knee) in respective figures (see also Fig. 3b), should be proportional (and of the order of)

till t = 500τQ, where the ramp is stopped and equilibrium value for N settles to 3 × 105. But for the actual evolution, the length of the period from t = tc = 0 up to the point denoted by A (a sharp knee) in respective figures (see also Fig. 3b), should be proportional (and of the order of)  and – in our SGPE case – should scale as

and – in our SGPE case – should scale as  . Our results confirm this scaling, as shown by the overlap of N around the knee, when plotted against

. Our results confirm this scaling, as shown by the overlap of N around the knee, when plotted against  for different τQ (Fig. 3b). After this knee point, N catches up rapidly with its equilibrium value. W and L/N also stabilize around A.

for different τQ (Fig. 3b). After this knee point, N catches up rapidly with its equilibrium value. W and L/N also stabilize around A.

Unlike other BEC relics of symmetry breaking (e.g., solitons), which are difficult to resolve due to thermal noise and decay due to dissipation, W bears a very stable and readable signature of the underlying phase transition due to its topological stability and integer nature. Statistics of W can be presumably studied, e.g. within the experimental setups such as27,28,29,30,31,33,34. Experimental study of the growth of BEC density with adjustable cooling rate parameter has been reported already by Esslinger group32 (cooling by sudden ramp of confining RF field) and within toroidal geometry by Anderson group15 (both with sudden and linear ramp of RF field). They observed the linear growth regime, as well as the “knee” feature that provides an experimental counterpart of the effective  . This should allow direct verification of the KZM scaling law and quantitative determination of the exponent for

. This should allow direct verification of the KZM scaling law and quantitative determination of the exponent for  . Moreover, experimental determination of the dynamical exponent z may be possible employing the KZM formulae ν/2(1 + νz) and 1/(1 + νz) for the measured values of 〈|W|〉 and effective

. Moreover, experimental determination of the dynamical exponent z may be possible employing the KZM formulae ν/2(1 + νz) and 1/(1 + νz) for the measured values of 〈|W|〉 and effective  exponents, Fig. 3(a) and 3(b), respectively and solving for ν, z. The scaling law involving N may be amenable to more accurate experimental determination, since the exponent for

exponents, Fig. 3(a) and 3(b), respectively and solving for ν, z. The scaling law involving N may be amenable to more accurate experimental determination, since the exponent for  scaling

scaling  is larger than that for the scaling of

is larger than that for the scaling of  . Note that for real BEC transition in 3D, theoretical prediction is ν = 2/3 (close to experimental value, 0.67 ± 0.13,44) and z = 3/2. Finally, the sample to sample fluctuations in the growth of N are much smaller than those of W (see Fig. 2) and hence requires less averaging over realizations.

. Note that for real BEC transition in 3D, theoretical prediction is ν = 2/3 (close to experimental value, 0.67 ± 0.13,44) and z = 3/2. Finally, the sample to sample fluctuations in the growth of N are much smaller than those of W (see Fig. 2) and hence requires less averaging over realizations.

Discussion

Our simulations reproduce scalings of the winding number and  predicted by KZM, but the “naive” random walk argument including Eq. (6) we have used to estimate < |W| > results in an overestimate by a factor f ~ 2.5. This discrepancy deserves a comment both because it is there and because it is surprisingly small: Factors f ~ 10 were reported in the past12,13,41.

predicted by KZM, but the “naive” random walk argument including Eq. (6) we have used to estimate < |W| > results in an overestimate by a factor f ~ 2.5. This discrepancy deserves a comment both because it is there and because it is surprisingly small: Factors f ~ 10 were reported in the past12,13,41.

We first note that KZM estimate – one  -sized defect fragment per domain of size

-sized defect fragment per domain of size  – is general and this generality is obtained at the price of focusing on what is dominant (scalings) and ignoring (subdominant) microphysics. For instance, it is clear that the estimate of

– is general and this generality is obtained at the price of focusing on what is dominant (scalings) and ignoring (subdominant) microphysics. For instance, it is clear that the estimate of  will depend on the noise temperature and on the nonlinearity parameter. Moreover, density of defects will depend on their nature and there are systems (such as 3He) where there are many different types of defects that can be created by the same transition and there is no reason for their densities to be the same.

will depend on the noise temperature and on the nonlinearity parameter. Moreover, density of defects will depend on their nature and there are systems (such as 3He) where there are many different types of defects that can be created by the same transition and there is no reason for their densities to be the same.

Detailed studies show that such additional inputs affect density estimates but are either subdominant (e.g., there is a logarithmic dependence on noise and nonlinearity, as can be expected from the nature of the instability after the quench43) or are too complicated for precise treatment (3He). However, these additional inputs do not change scaling of  and therefore, scaling of the number of topological defects with the quench rate.

and therefore, scaling of the number of topological defects with the quench rate.

This focus on scalings is very much in the spirit of the renormalization approach to second order phase transitions: Microphysics sets dimensionfull inputs that determine healing length and relaxation time, but scalings of these two quantities near the critical point are independent of microphysical details. This allows for the classification of second order phase transitions in terms of critical exponents. Similarly, KZM predicts scalings, but only estimates prefactors.

In contrast to past numerical experiments (where defect separations were typically  , with f ~ 10) we have seen KZM estimates of winding numbers only a factor of about 2.5 larger than the numerical estimates. This improved accuracy is because – in contrast to past exercises of this sort – in the constrained problem we have addressed we were able to be more precise in taking “SGPE microphysics” into account. Thus, we have estimated that domains of size

, with f ~ 10) we have seen KZM estimates of winding numbers only a factor of about 2.5 larger than the numerical estimates. This improved accuracy is because – in contrast to past exercises of this sort – in the constrained problem we have addressed we were able to be more precise in taking “SGPE microphysics” into account. Thus, we have estimated that domains of size  will have phases that differ by

will have phases that differ by  and the geometry of the problem allowed us to avoid some of the difficult questions concerning dynamics of the post-quench phase ordering. However, these inputs are still only estimates: It is clear from Fig. 1 that different “beads” of the newly formed BEC do not have the same size. Moreover, it is quite likely that early on – around the time when the condensate begins to encompass the whole torus – winding number can change (see Fig. 2). Last not least, the instant when this seems to happen scales in accord – but does not coincide – with the estimate of

and the geometry of the problem allowed us to avoid some of the difficult questions concerning dynamics of the post-quench phase ordering. However, these inputs are still only estimates: It is clear from Fig. 1 that different “beads” of the newly formed BEC do not have the same size. Moreover, it is quite likely that early on – around the time when the condensate begins to encompass the whole torus – winding number can change (see Fig. 2). Last not least, the instant when this seems to happen scales in accord – but does not coincide – with the estimate of  .

.

We conclude this part of the discussion by noting that KZM is a general theory of the dynamics of second order phase transitions, but that – like the universality classes on which it is based – it largely ignores microphysical details and does not aim to predict dimensionfull prefactors. Thus, while a more careful estimate of the expected magnitudes of winding numbers are possible in the simple model we have examined, the real aim of KZM and a good way to test it is to verify that it correctly predicts scalings of the topological relics of the transition from the critical exponents (which, for the real BEC, are anyway different than in the case of our SGPE model). Toroidal BEC traps are needed for this and they are not the “popular model”. Fortunately, our study suggests an alternative, more limited but also potentially more accessible possibility – testing for the scaling of delay in BEC density growth.

Predictions of KZM can be substantially perturbed by natural sources of experimental imperfections in the form of inhomogeneity in the potential. An overall non-uniformity may have many causes. To be specific, we shall think of tilting the torus in the gravitational field. This is represented by an additional potential of the form  where α represents the tilting angle,

where α represents the tilting angle,  is the angular coordinate denoting the position on the ring, R = C/2π and g the gravitational acceleration. Different stages of condensate formation in the tilted ring are shown in Fig. 1 (lower row). Fig. 4(a) shows suppression of W as the function of α. Inset of Fig. 4(b) shows that the scaling behavior still persists for very small tilting of α = 0.5°, but the exponent increases. The main Fig. 4(b) shows the disappearance of the KZM scaling for slightly bigger tilting (α = 1°). Suppression of W could be caused in the tilted ring due to the competition between the finite velocity vF of the critical front (determined by the critical condition set locally by the inhomogeneity6) and the relevant sound velocity

is the angular coordinate denoting the position on the ring, R = C/2π and g the gravitational acceleration. Different stages of condensate formation in the tilted ring are shown in Fig. 1 (lower row). Fig. 4(a) shows suppression of W as the function of α. Inset of Fig. 4(b) shows that the scaling behavior still persists for very small tilting of α = 0.5°, but the exponent increases. The main Fig. 4(b) shows the disappearance of the KZM scaling for slightly bigger tilting (α = 1°). Suppression of W could be caused in the tilted ring due to the competition between the finite velocity vF of the critical front (determined by the critical condition set locally by the inhomogeneity6) and the relevant sound velocity  at which the correlation is established between the condensate phase. Formation of phase-inhomogeneity (local flow) is suppressed wherever

at which the correlation is established between the condensate phase. Formation of phase-inhomogeneity (local flow) is suppressed wherever  , since phase correlation is maintained throughout the condensation process there: the newborn condensate selects the same phase as the existing condensate due to local free-energy minimization6,45,46. This implies steeper fall of 〈|W|〉 with τQ6. But in our case, the above condition is not met for α = 0.5°. The same criteria also cannot explain the suppression of W for α = 1° (Fig. 4b). One possible explanation of this suppression may lie in the dissipation of kinetic energy prior to the formation of the complete BEC ring. The local flows generated by KZM at the bottom of the ring are susceptible to dissipation before the topological constraint (that protects the quantized circulation) is imposed, i.e., before the BEC is formed completely up to the ring top. Such early energy loss might leave the condensate with kinetic energy insufficient for quantized circulation. We note that tilting a BEC ring experimentally and applying that to offset inadvertent horizontal misalignment has been achieved recently34, so while we have not developed the theory of various imperfections (exemplified here by tilting in the gravitational field), control with the accuracies that may compensate for (or avoid) such problems seems possible.

, since phase correlation is maintained throughout the condensation process there: the newborn condensate selects the same phase as the existing condensate due to local free-energy minimization6,45,46. This implies steeper fall of 〈|W|〉 with τQ6. But in our case, the above condition is not met for α = 0.5°. The same criteria also cannot explain the suppression of W for α = 1° (Fig. 4b). One possible explanation of this suppression may lie in the dissipation of kinetic energy prior to the formation of the complete BEC ring. The local flows generated by KZM at the bottom of the ring are susceptible to dissipation before the topological constraint (that protects the quantized circulation) is imposed, i.e., before the BEC is formed completely up to the ring top. Such early energy loss might leave the condensate with kinetic energy insufficient for quantized circulation. We note that tilting a BEC ring experimentally and applying that to offset inadvertent horizontal misalignment has been achieved recently34, so while we have not developed the theory of various imperfections (exemplified here by tilting in the gravitational field), control with the accuracies that may compensate for (or avoid) such problems seems possible.

Winding up a tilted BEC ring.

(a) 〈|W|〉 vs α for τQ = 0.1 (other parameters same as in Fig. 2). (b) Suppression of scaling behavior of 〈|W|〉 with τQ for α = 1°. The inset shows scaling behavior for smaller tilt of α = 0.5° with a larger exponent 0.158 ± 0.011.

For very slow quenches (large τQ), however, |W| doesn't vanish in the tilted case, as the density doesn't grow on the top till the critical front reaches the top and topological protection doesn't apply till then. If this period is long enough, thermal fluctuations may create sufficient random walks in phase to induce a net circulation by the time the density becomes significant everywhere. The resulting circulation may hence even grow with τQ in this regime, as seen from the Fig. 4.

To summarize, we showed that temperature quench through the critical point can produce spontaneous circulation of BEC in a ring and verified long standing scaling predictions of KZM3. Our demonstration involving winding number and condensate density paves a way for experimental verification of KZM scaling laws. It also provides prescription for experimental determination of the critical exponents of the underlying BEC transition.

Methods

We simulate the quasi-1D BEC by integrating 1-D Stochastic Gross Pitaevskii equation (Eq. 1) numerically using 4th order adaptive step-size Runge-Kutta algorithm for > 1000 noise realisations. The observables are extracted through averaging over the ensemble15,50. The initial state for the evolution of Eq. (1) is a thermal state obtained integrating Eq. (1) with constant  fixed to its large initial value, for an integration time > 1000τ0 to ensure thermalisation. The temperature quench of the thermal cloud is simulated through a ramp in the chemical potential (

fixed to its large initial value, for an integration time > 1000τ0 to ensure thermalisation. The temperature quench of the thermal cloud is simulated through a ramp in the chemical potential ( ), keeping the noise amplitude T and the damping γ constant. This approximation captures the essential universal aspects of the dynamics. The symmetry breaking underlying the transition is induced by the change in

), keeping the noise amplitude T and the damping γ constant. This approximation captures the essential universal aspects of the dynamics. The symmetry breaking underlying the transition is induced by the change in  (see the discussion following Eq. 1). Changes in T and γ give only non-universal quantitative corrections7,13. A similar method was successfully used in Ref. 15 in the framework of the stochastic (projected) Gross-Pitaevskii equation (SPGPE) to model evaporative cooling of a pancake shaped thermal cloud and study the statistics of trapped vortices and found good agreement between experimental and numerical results. The SGPE and the SPGPE have been used before to model experimental results with success15,35,36,47,48,49.

(see the discussion following Eq. 1). Changes in T and γ give only non-universal quantitative corrections7,13. A similar method was successfully used in Ref. 15 in the framework of the stochastic (projected) Gross-Pitaevskii equation (SPGPE) to model evaporative cooling of a pancake shaped thermal cloud and study the statistics of trapped vortices and found good agreement between experimental and numerical results. The SGPE and the SPGPE have been used before to model experimental results with success15,35,36,47,48,49.

To make direct connection of our simulation with experiments, we note that the one dimensional approximation of a thin 3D torus with thickness  is obtained by integrating out the transverse (y and z in our case) degrees of freedom. Such a confinement-induced quasi-one dimensional Bose system is equivalent to a purely one-dimensional system with a modified interaction strength

is obtained by integrating out the transverse (y and z in our case) degrees of freedom. Such a confinement-induced quasi-one dimensional Bose system is equivalent to a purely one-dimensional system with a modified interaction strength  given by the confinement frequencies. For isotropic harmonic confinement in the transverse direction with confinement frequency ω0 we have

given by the confinement frequencies. For isotropic harmonic confinement in the transverse direction with confinement frequency ω0 we have  , where m is the mass of the atom, a is the scattering length and

, where m is the mass of the atom, a is the scattering length and  . The three dimensional wave function φ(x, y, z) may be reconstructed from the one-dimensional wave function φ(x) by assuming Gaussian profile in the transverse directions: φ(x, y, z) = φ(x)φ0(y, z), where

. The three dimensional wave function φ(x, y, z) may be reconstructed from the one-dimensional wave function φ(x) by assuming Gaussian profile in the transverse directions: φ(x, y, z) = φ(x)φ0(y, z), where  . Such reconstructions are shown in Fig. 1 and in the Supplementary Movie. The Supplementary Movie shows the real-time dynamics of the condensation process illustrating the key features of the dynamics germane to verification of KZM and determination of critical exponents, namely, stabilization of W at the wake of the condensation and the knee-like behavior of the density growth (also clearly shown in the corresponding Supplementary Fig.). The simulation is done by integrating dimensionful SGPE with parameter values: a0 = 100 × aB (aB = Bohr radius), m = mass of a Rb atom, ω0 = 200 × 2π, γ = 0.01 and T = 10 nK. All these parameters are compatible with the experimental set up in28,29.

. Such reconstructions are shown in Fig. 1 and in the Supplementary Movie. The Supplementary Movie shows the real-time dynamics of the condensation process illustrating the key features of the dynamics germane to verification of KZM and determination of critical exponents, namely, stabilization of W at the wake of the condensation and the knee-like behavior of the density growth (also clearly shown in the corresponding Supplementary Fig.). The simulation is done by integrating dimensionful SGPE with parameter values: a0 = 100 × aB (aB = Bohr radius), m = mass of a Rb atom, ω0 = 200 × 2π, γ = 0.01 and T = 10 nK. All these parameters are compatible with the experimental set up in28,29.

References

Kibble, T. W. B .Topology of cosmic domains and strings. J. Phys. A 9, 1387 (1976).

Kibble, T. W. B. Some implications of a cosmological phase transition. Phys. Rep. 67, 183–199 (1980).

Zurek, W. H. Cosmological experiments in superfluid helium? Nature 317, 505–508 (1985).

Zurek, W. H. Cosmic strings in laboratory superfluids. Acta Phys. Pol. B 24, 1301 (1993).

Zurek, W. H. Cosmological experiments in condensed matter systems. Phys. Rep. 276, 177 (1996).

Zurek, W. H. Causality in condensates: gray solitons as relics of BEC formation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 105702 (2009).

Damski, B. & Zurek, W. H. Soliton creation during a Bose-Einstein condensation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 160404 (2010).

Witkowska, E., Deuar, P., Gajda, M. & Rzazewski, M. Solitons as the early stage of quasicondensate formation during evaporative cooling. Phys. Rev. Lett 106, 135301 (2011).

Damski, B. & Zurek, W. H. How to fix a broken symmetry: quantum dynamics of symmetry restoration in a ferromagnetic Bose-Einstein condensate. New J. Phys. 10, 045023 (2008).

Damski, B. & Zurek, W. H. Quantum phase transition in space in a ferromagnetic spin-1 Bose-Einstein condensate. New J. Phys. 11, 063014 (2009).

Dziarmaga, J. Dynamics of a quantum phase transition and relaxation to a steady state. Adv. Phys. 59, 1063–1189 (2010).

Laguna, P. & Zurek, W. H. Density of kinks after a quench: when symmetry breaks, how big are the pieces? Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 2519 (1997).

Laguna, P. & Zurek, W. H. Critical dynamics of symmetry breaking: quenches, dissipation and cosmology. Phys. Rev. D 58, 085021 (1998).

del Campo, A., De Chiara, G., Morigi, G., Plenio, M. B. & Retzker, A. Structural defects in ion chains by quenching the external potential: the inhomogeneous Kibble-Zurek mechanism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 075701 (2010).

Weiler, C. N., Neely, T. W., Scherer, D. R., Bradley, A. S., Davis, M. J. & Anderson, P. B. Spontaneous vortices in the formation of Bose-Einstein condensates. Nature 455, 948–951 (2008).

Scherer, D. R., Weiler, C. N., Neely, T. W. & Anderson, P. B. Vortex Formation by Merging of Multiple Trapped Bose-Einstein Condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 110402 (2007).

Sadler, L. E., Higbie, J. M., Leslie, S. R., Vengalattore, M. & Stamper-Kurn, D. M. Spontaneous symmetry breaking in a quenched ferromagnetic spinor Bose-Einstein condensate. Nature 443, 312–315 (2006).

Maniv, A., Polturak, E. & Koren, G. Observation of magnetic flux generated spontaneously during a rapid quench of superconducting films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 197001 (2003).

Monaco, R., Mygind, J., Aaroe, M., Rivers, R. J. & Koshelets, V. P. Zurek-Kibble mechanism for the spontaneous vortex formation in Nb-Al/Alox/Nb Josephson tunnel junctions: new theory and experiment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 180604 (2006).

Bauerle, C., Bunkov,. Bauerle, C., Bunkov,. Yu, M., Fisher, S. N. Godfrin, H. & Pickett, G. R. Laboratory simulation of cosmic string formation in the early Universe using superfluid 3He. Nature 382, 332–334 (1996).

Ruutu, V. M. H. et al. Vortex formation in neutron-irradiated superfluid 3He as an analogue of cosmological defect formation. Nature 382, 334–336 (1996).

Golubchik, D., Polturak, E. & Koren G. Evidence for long-range correlations within arrays of spontaneously created magnetic vortices in a Nb thin-film superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 247002 (2010).

Monaco, R., Mygind, J., Rivers, R. J. & Koshelets, V. P. Spontaneous fluxoid formation in superconducting loops. Phys. Rev. B 80, 180501(R) (2009).

Monaco, R., Mygind, J. & Rivers, R. J. Zurek-Kibble domain structures: the dynamics of spontaneous vortex formation in annular Josephson tunnel junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 080603 (2002).

Monaco, R., Mygind, J. & Rivers, R. J. Spontaneous fluxon formation in annular Josephson tunnel junctions. Phys Rev. B 67, 104506 (2003).

Ueda, M., Kawaguchi, Y., Saito,. Kanamoto, H. R. & Nakajima, T. Symmetry breaking in Bose-Einstein condensates. AIP Conf. Proc. 869, 165 (2006).

Ryu, C. et al. Observation of Persistent Flow of a Bose-Einstein Condensate in a Toroidal Trap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 260401 (2007).

Henderson, K., Ryu, C., MacCormick, C. & Boshier, M. G. Experimental demonstration of painting arbitrary and dynamic potentials for Bose-Einstein condensates. New J Phys. 11, 043030 (2009).

Research Highlight of 28, Quantum physics: atomic painting. Nature459, 142 (2009).

Gupta, S., Murch, K. W., Moore, K. L., Purdy, T. P. & Stamper-Kurn, D. M. Bose-Einstein condensation in a circular waveguide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 143201 (2005).

Görlitz, A. et al. Realization of Bose-Einstein Condensates in lower dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 130402 (2001).

Köhl, M., Davis, M. J., Gardiner, C. W., Hänsch, T. W. & Esslinger, T. Growth of Bose-Einstein condensates from thermal vapor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 080402 (2002).

Ramanathan, A. et al. Superflow in a Toroidal Bose-Einstein Condensate: An Atom Circuit with a Tunable Weak Link. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 130401 (2011).

Sherlock, B. E., Gildemeister, M., Owen, E., Nugent, E. & Foot, C. J. Time-averaged adiabatic ring potential for ultracold atoms arXiv.:1102.2895v3 (2011).

Blakie, P. B., Bradley, A. S., Davis, M. J., Ballagh, R. J. & Gardiner, C. W. Dynamics and statistical mechanics of ultra-cold Bose gases using c-field techniques. Adv. Phys. 57, 363–455 (2008).

Cockburn, S. P. & Proukakis, N. P. The stochastic Gross-Pitaevskii equation and some applications. Laser Phys. 19, 558–570 (2009).

Stoof, H. T. C. & Bijlsma, M. J. Dynamics of Fluctuating Bose-Einstein Condensates. J. Low Temp. Phys. 124, 431–442 (2001).

Saito, H., Kawaguchi, Y. & Ueda, M. Kibble-Zurek mechanism in a quenched ferromagnetic Bose-Einstein condensate. Phys. Rev. A 76, 043613 (2007).

Dziarmaga, J., Meisner, J. & Zurek, W. H. Winding up of the wave-function phase by an insulator-to-superfluid transition in a ring of coupled Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 115701 (2008).

Reppy, J. D. & Depatie, D. Persistent Currents in Superfluid Helium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 12 187 (1964).

Antunes, N. D., Bettencourt, L. M. A. & Zurek, W. H. Vortex string formation in a 3D U(1) temperature quench. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 2824 (1999).

Damski, B. & Zurek, W. H. Dynamics of a Quantum Phase Transition in a Ferromagnetic Bose-Einstein Condensate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 130402 (2007).

Lythe, G. Stochastic PDEs: Domain Formation in Dynamic Transitions. Anales de Física 4, 55–63 (1998).

Donner, T. et al. Critical Behavior of a Trapped Interacting Bose Gas. Science 315, 1556–1558 (2007).

Kibble, T. W. B. & Volovik, G. E. On phase ordering behind the propagating front of a second-order transition. JETP Lett. 65, 102–107 (1997).

Dziarmaga, J., Laguna, P. & Zurek, W. H. Symmetry breaking with a slant: Topological defects after an inhomogeneous quench. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 4749 (1999).

Bradley, A. S., Gardiner, C. W. & Davis, M. J. Bose-Einstein condensation from a rotating thermal cloud: Vortex nucleation and lattice formation. Phys. Rev. A 77, 033616 (2008).

Gardiner, C. W., Anglin, J. R. & Fudge, T. I. A. The stochastic Gross-Pitaevskii equation. J. Phys. B 35, 1555 (2002).

Cockburn, S., Gallucci, D. & Proukakis N. Quantitative study of quasi-one-dimensional Bose gas experiments via the stochastic Gross-Pitaevskii equation. Phys. Rev. A 84, 023613 (2011).

Davis, M. J. & Gardiner, C. Growth of a Bose-Einstein condensate: a detailed comparison of theory and experiment. J. Phys. B 35, 733 (2002).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support of U.S. Department of Energy through the LANL/LDRD Program. J.S. acknowledges support of Australian Research Council through the ARC Centre of Excellence for Quantum-Atom Optics. We thank B. Damski and M.J. Davis for useful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the theoretical analysis, interpretation of the numerical data and the preparation of the manuscript. AD and JS carried out the numerical simulations. WHZ proposed and directed the project.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Das, A., Sabbatini, J. & Zurek, W. Winding up superfluid in a torus via Bose Einstein condensation. Sci Rep 2, 352 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00352

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00352

This article is cited by

-

Holographic topological defects in a ring: role of diverse boundary conditions

Journal of High Energy Physics (2022)

-

Topological defects formation with momentum dissipation

Journal of High Energy Physics (2021)

-

Universal statistics of vortices in a newborn holographic superconductor: beyond the Kibble-Zurek mechanism

Journal of High Energy Physics (2021)

-

Topological defects as relics of spontaneous symmetry breaking from black hole physics

Journal of High Energy Physics (2021)

-

Dynamical equilibration across a quenched phase transition in a trapped quantum gas

Communications Physics (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.