Abstract

The smaller the system, typically - the higher is the impact of fluctuations. In narrow superconducting wires sufficiently close to the critical temperature Tc thermal fluctuations are responsible for the experimentally observable finite resistance. Quite recently it became possible to fabricate sub-10 nm superconducting structures, where the finite resistivity was reported within the whole range of experimentally obtainable temperatures. The observation has been associated with quantum fluctuations capable to quench zero resistivity in superconducting nanowires even at temperatures T→0. Here we demonstrate that in tiny superconducting nanorings the same phenomenon is responsible for suppression of another basic attribute of superconductivity - persistent currents - dramatically affecting their magnitude, the period and the shape of the current-phase relation. The effect is of fundamental importance demonstrating the impact of quantum fluctuations on the ground state of a macroscopically coherent system and should be taken into consideration in various nanoelectronic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thermodynamic fluctuations become more important when dimensions of a system are reduced. It has been known for decades that in narrow quasi-1D superconducting channels thermal fluctuations enable zero resistance only at temperatures noticeably below the critical temperature Tc1,2,3,4. Quite recently it has been demonstrated that qualitatively different phenomenon - quantum fluctuations - also called quantum phase slips – can suppress the dissipationless electric current in ultra-narrow superconducting nanowires with characteristic diameter d∼10 nm even at temperatures T→05,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 setting the ultimate limit for utilization of superconducting nanoelectronic components. Zero resistivity, detected in transport experiments, being probably the most famous ‘text-book’ manifestation of superconductivity, characterizes the non-equilibrium state of a superconductor. On the contrary, persistent current (PC) circulating in a superconductor exposed to an external magnetic field is the thermodynamically equilibrium characteristic of the system.

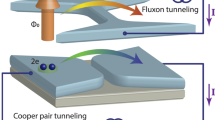

The impact of fluctuations on equilibrium properties of a quantum system is a very intriguing topic. Of particular interest is the prediction that in ultra-narrow superconducting nanorings exposed to external magnetic field the quantum fluctuations should induce a gap in the energy spectrum forming a band structure and degenerate the PC saw-tooth current-phase dependence into a smooth sine-type13,11 (Fig. 1, dotted lines). Direct measurement of the impact of fluctuations on magnetic momentum of PCs circulating in a nanoscale superconducting sample is a rather demanding experimental task. To our best knowledge, so far the corresponding experiments were reported only sufficiently close to the critical temperature Tc14,15 where the ‘classical’ thermal fluctuations provide the dominating contribution16,17. The objective of our work was to study the qualitatively different limit: ultra-low temperatures and ultra-narrow samples where the impact of thermal fluctuations can be disregarded, while quantum fluctuations should manifest themselves. For probing PCs we employed solid state tunneling technique (for details see Methods). The method provides maximum sensitivity for homogeneous uniform samples, eliminating those ones where the existence of undesired weak link(s) may mimic the effects under interest. The extensive analysis of the whole set of experimental data and the alternative explanations allows us to state, that the most plausible explanation for our findings is indeed related to the quantum phase slip phenomenon. The effect should be taken into consideration in various nanoelectronic applications and is of fundamental and universal importance reflecting the impact of quantum fluctuations on the ground state of a macroscopically coherent system.

Schematic dependence of energy E, persistent current IS and tunnel current Itun on normalized magnetic flux Φ/Φ0.

(a) Quantized energy spectrum En of a thin-walled superconducting ring. Solid thick line corresponds to the evolution of the system following the ground state, dashed line – metastable states and dots – the limit of quantum fluctuations. (b) Corresponding dependence of the persistent current Is. Horizontal dashed line represents the critical current Ic setting the ultimate limit for the magnitude of a persistent current circulating in the loop. (c) Corresponding dependence of the tunnel current Itun.

Results

Let us first outline the main features of the model which supports the experimental findings presented below. The energy levels En of a thin-walled superconducting ring threaded by magnetic flux Φ are given by the set of parabolas (Fig. 1a). If the system follows the ground state, the evolution of the energy in magnetic field is represented in Fig. 1a by the thick solid line with periodicity strictly equal to one flux quantum  . The scenario is typical for experiments made sufficiently close to the critical temperature Tc18,14 or to systems containing weak links – SQUIDs. The corresponding dependence of PC on magnetic flux

. The scenario is typical for experiments made sufficiently close to the critical temperature Tc18,14 or to systems containing weak links – SQUIDs. The corresponding dependence of PC on magnetic flux  follows the single flux quantum periodicity (Fig. 1b, thick solid line) with the well-known saw-tooth pattern, which can be smeared if the contribution of thermal fluctuations is essential

follows the single flux quantum periodicity (Fig. 1b, thick solid line) with the well-known saw-tooth pattern, which can be smeared if the contribution of thermal fluctuations is essential

At temperatures  the system can be ‘frozen’ in a metastable state n without relaxing to the neighboring quantum level n±1. In this low temperature limit the periodicity of PC oscillations may significantly exceed one flux quantum19,20. Transition to another quantum state, triggered by an ‘external disturbance’, happens when:

the system can be ‘frozen’ in a metastable state n without relaxing to the neighboring quantum level n±1. In this low temperature limit the periodicity of PC oscillations may significantly exceed one flux quantum19,20. Transition to another quantum state, triggered by an ‘external disturbance’, happens when:

where G is the current-dependent energy gap of the superconductor and  represents the cumulative impact of all non-thermal contributions. In the ‘classical’ limit

represents the cumulative impact of all non-thermal contributions. In the ‘classical’ limit  Eq.(1) is equivalent to the trivial condition: maximum PC equals the critical current

Eq.(1) is equivalent to the trivial condition: maximum PC equals the critical current  (Fig. 1b, horizontal line). At sufficiently low temperatures (and negligible external disturbance) one should observe periodicity

(Fig. 1b, horizontal line). At sufficiently low temperatures (and negligible external disturbance) one should observe periodicity  if the loop circumference S is much larger than the superconducting coherence length ξ20. PCs approaching sub-critical values broaden the superconducting density of states (DOS)21

if the loop circumference S is much larger than the superconducting coherence length ξ20. PCs approaching sub-critical values broaden the superconducting density of states (DOS)21  which can be found from the self-consistent solution of the Usadel and gap equations for the pairing potential Δ:

which can be found from the self-consistent solution of the Usadel and gap equations for the pairing potential Δ:

where Γ is the deparing energy; θ is the pairing angle; N(0), Veff and ΘDeb are the normal state DOS, pairing strength and Debye energy. If the superconducting loop is a part of a tunnel structure, then the periodic modulation of DOS results in tunnel current oscillations (Fig. 1c)22,23. Supported by the known expression for En(Φ) and the current dependence of the deparing energy Γ(Is), expressions (1)–(3) form a complete set of equations enabling quantitative analysis22,23. At magnetic fields much smaller than the critical one the direct deparing by magnetic field Γ(B) can be neglected compared to the corresponding current dependence Γ(Is).

For a given material in the ‘classical’ limit  the large period of Is (or, alternatively, Itun) oscillations in units ΔΦ/Φ0 (Fig. 1 dashed lines and Fig. 3a) is determined exclusively by the loop circumference S and does not depend on the cross section σ of the wire forming the loop, as long as the condition of one-dimensionality σ1/2<ξ is satisfied. In the ‘quantum’ limit of extremely narrow loops when the rate of quantum fluctuations

the large period of Is (or, alternatively, Itun) oscillations in units ΔΦ/Φ0 (Fig. 1 dashed lines and Fig. 3a) is determined exclusively by the loop circumference S and does not depend on the cross section σ of the wire forming the loop, as long as the condition of one-dimensionality σ1/2<ξ is satisfied. In the ‘quantum’ limit of extremely narrow loops when the rate of quantum fluctuations  11 exceeds all other sources of disturbance, the shape of oscillations should demonstrate smooth quasi-sinusoidal pattern13,11 of much smaller amplitude (Fig. 1, dots and Figs. 3c and 4). Calculation of the tunnel current Itun(Φ) in presence of quantum fluctuations is not trivial: strictly speaking, Eqs. (2)–(3) are valid only when the pairing potential Δ is a well-defined parameter, which is not the case in a fluctuation regime. Nevertheless we believe some estimates can be made.

11 exceeds all other sources of disturbance, the shape of oscillations should demonstrate smooth quasi-sinusoidal pattern13,11 of much smaller amplitude (Fig. 1, dots and Figs. 3c and 4). Calculation of the tunnel current Itun(Φ) in presence of quantum fluctuations is not trivial: strictly speaking, Eqs. (2)–(3) are valid only when the pairing potential Δ is a well-defined parameter, which is not the case in a fluctuation regime. Nevertheless we believe some estimates can be made.

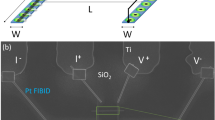

Oscillations of the normalized tunnel current  in external magnetic flux Φ/Φ0 of three Al-AlOx-Al-AlOx-Al structures with the same area of the aluminum loop S = 19.6 μm2.

in external magnetic flux Φ/Φ0 of three Al-AlOx-Al-AlOx-Al structures with the same area of the aluminum loop S = 19.6 μm2.

Experimental data are shown by circles (○), calculations – by lines. (a) Large period ( ) and magnitude (

) and magnitude ( ) oscillations in the structure with loop formed by 110 nm × 75 nm wire,

) oscillations in the structure with loop formed by 110 nm × 75 nm wire, ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  . The monotonous increase of the base line is due to the gap reduction by magnetic field noticeable at biases close to the gap edge

. The monotonous increase of the base line is due to the gap reduction by magnetic field noticeable at biases close to the gap edge  . (b) Oscillations with variable period in the narrower (ion milled) sample,

. (b) Oscillations with variable period in the narrower (ion milled) sample,  ,

,  ,

,  . Solid line represents calculations at the intermediate limit with Te = 70 mK and

. Solid line represents calculations at the intermediate limit with Te = 70 mK and  resulting in

resulting in  period, dashed line - calculated

period, dashed line - calculated  oscillations in a slightly narrower loop

oscillations in a slightly narrower loop  . (c) Same sample as in (b) further gently ion milled at

. (c) Same sample as in (b) further gently ion milled at  and

and  . Solid line corresponds to calculations in the QPS limit with

. Solid line corresponds to calculations in the QPS limit with  and

and  with the same parameters used to fit R(T) dependencies of Al nanowires9,10. Left insets - flux dependencies of the characteristic energies: superconducting pairing potential

with the same parameters used to fit R(T) dependencies of Al nanowires9,10. Left insets - flux dependencies of the characteristic energies: superconducting pairing potential  , spectral gap

, spectral gap  , deparing energy

, deparing energy  , rate of quantum fluctuations

, rate of quantum fluctuations  and the corresponding thermal energy kBT (-). Right insets – calculated flux dependence of the persistent current Is(Φ) normalized by the critical current Ic(0). Note the change of the shape, reduction of the magnitude and the period of both the tunnel and the persistent current oscillations. In the classic (a) and intermediate (b) regimes the periodicity of oscillations is defined by Eq. (1), while in the essentially QPS regime (c) – by Eq. (4). For details – see the text.

and the corresponding thermal energy kBT (-). Right insets – calculated flux dependence of the persistent current Is(Φ) normalized by the critical current Ic(0). Note the change of the shape, reduction of the magnitude and the period of both the tunnel and the persistent current oscillations. In the classic (a) and intermediate (b) regimes the periodicity of oscillations is defined by Eq. (1), while in the essentially QPS regime (c) – by Eq. (4). For details – see the text.

Tunnel current Itun oscillations in external magnetic flux Φ/Φ0 of Al-AlOx-Ti-AlOx-Al structure with the area of the titanium loop S = 18.9 μm2.

Top data - for non ion milled sample  , bottom data - for sputtered sample

, bottom data - for sputtered sample  ,

,  at the same bias

at the same bias  . Solid lines represent QPS limit calculations assuming

. Solid lines represent QPS limit calculations assuming  ,

,  and 56 nm, respectively and the same parameters used to fit R(T) dependencies of Ti nanowires12. Note the drop of the oscillation amplitude by a factor of ∼6 when the diameter σ1/2is reduced just by ∼ 10%. Inset shows simulation: for the same fitting parameters of the ion milled sample - what would be the tunnel current oscillations in the intermediate limit (similar to Fig. 3b). For details – see the text.

and 56 nm, respectively and the same parameters used to fit R(T) dependencies of Ti nanowires12. Note the drop of the oscillation amplitude by a factor of ∼6 when the diameter σ1/2is reduced just by ∼ 10%. Inset shows simulation: for the same fitting parameters of the ion milled sample - what would be the tunnel current oscillations in the intermediate limit (similar to Fig. 3b). For details – see the text.

The QPS contribution becomes important when  , where

, where  , A - material constant, RN – normal state resistance of the loop,

, A - material constant, RN – normal state resistance of the loop,  quantum resistance. Even in the regime of weak quantum fluctuations

quantum resistance. Even in the regime of weak quantum fluctuations  the dependence Is(Φ) already deviates from the saw-tooth11 (Fig. 3c, right inset):

the dependence Is(Φ) already deviates from the saw-tooth11 (Fig. 3c, right inset):

where e,  and m* and nsare charge, mean free path, effective mass and density of superconducting electrons. To obtain the Itun(Φ) dependencies to be compared with the experiment Eq. (4) should be solved self-consistently with Eqs. (2)–(3).

and m* and nsare charge, mean free path, effective mass and density of superconducting electrons. To obtain the Itun(Φ) dependencies to be compared with the experiment Eq. (4) should be solved self-consistently with Eqs. (2)–(3).

Modeling of the ‘intermediate’ regime  is, as usual, the most difficult. In this intermediate case, from the very general considerations, one might expect the magnitude and the period of PC oscillations to be reduced, compared to the ‘classical’ regime, demonstrating variable oscillations due to the stochastic nature of a disturbance quenching the oscillations before the condition Is = Ic(T) is reached (Fig. 3b). Unless the oscillations are completely suppressed in the limit of a non-negligible ‘disturbance’

is, as usual, the most difficult. In this intermediate case, from the very general considerations, one might expect the magnitude and the period of PC oscillations to be reduced, compared to the ‘classical’ regime, demonstrating variable oscillations due to the stochastic nature of a disturbance quenching the oscillations before the condition Is = Ic(T) is reached (Fig. 3b). Unless the oscillations are completely suppressed in the limit of a non-negligible ‘disturbance’  , the dependencies Is(Φ) and Itun(Φ) should follow the saw-tooth pattern: linear and curved, respectively (Figs. 1b,c (solid and dashed lines) and Figs. 3a,b). For the utilized dimensions of the loops (Fig. 2) the contribution of the geometrical inductance can be neglected. The energy related to the kinetic inductance

, the dependencies Is(Φ) and Itun(Φ) should follow the saw-tooth pattern: linear and curved, respectively (Figs. 1b,c (solid and dashed lines) and Figs. 3a,b). For the utilized dimensions of the loops (Fig. 2) the contribution of the geometrical inductance can be neglected. The energy related to the kinetic inductance  is always the largest energy scale enabling consideration of the QPS-mediated gap (Fig. 1a, dots) as a small perturbation imposed on the parabolic energy spectrum (Fig. 1a, solid lines). The smallness of the fluctuation rate EQPS/h justifies utilization of Eq. (4) and the employed model which is based on the assumption that the QPS are relatively rare events5,6.

is always the largest energy scale enabling consideration of the QPS-mediated gap (Fig. 1a, dots) as a small perturbation imposed on the parabolic energy spectrum (Fig. 1a, solid lines). The smallness of the fluctuation rate EQPS/h justifies utilization of Eq. (4) and the employed model which is based on the assumption that the QPS are relatively rare events5,6.

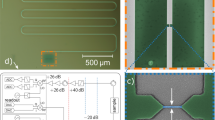

Microscopic images of the structures.

(a) SEM image of a S1-I-S2-I-S1 tunnel structure with the loop having ‘ears’ at the poles; and schematic of measurements. (b) SEM image of sputtered Al-AlOx-Ti-AlOx-Al structure without ‘ears’. The inset shows the magnified view of the equatorial part of the loop. Blurred bright edge is the pedestal formed by the sputtered Si/SiOx substrate. (c) TEM image of the thinnest part of a typical Ti structure after the cross section reduction using ion milling. The polycrystalline structure of compactly packed grains with the average size ∼ 3 nm does not contain obvious defects and is indistinguishable from the original (non ion milled) samples. The bright layer on top of both the Ti and the Si substrate is Pt deposited after the measurements solely for the purposes of the TEM analysis. (d) AFM image of the thinnest (equatorial) part of Ti loop after ion milling. Inset demonstrates the spatial variation of the height measured along the same sample. Note the extreme smoothness of the surface ± 2 nm originating from the polishing effect provided by the low energetic Ar+ ions.

Summarizing the theoretical background, one may conclude that at low temperatures  for a superconducting loop of a given area and circumference

for a superconducting loop of a given area and circumference  the reduction of the cross section σ of the wire forming the loop should lead to a qualitative changes in the PC oscillation pattern. For ‘thick’ loops the period

the reduction of the cross section σ of the wire forming the loop should lead to a qualitative changes in the PC oscillation pattern. For ‘thick’ loops the period  , the magnitude is large and shape is saw-tooth (Fig. 1, dashed lines)19,20,22. While in ‘thin’ samples the quantum fluctuations should degenerate the PC oscillations into smooth sine-type pattern with much smaller magnitude and strictly one flux periodicity (Fig. 1, dotted lines)13,11. For straightforwardness of interpretation the outlined scenario assumes that both the thick and the thin samples are homogeneous metallic loops containing no weak links. However, it should be noted that for high transparency barriers between the superconducting grains the model13, developed for a loop formed by a chain of weak links, converges to the homogeneous (metallic) loop model11. The observation naturally eliminates the distinction between a chain of weak links and a homogeneous superconducting channel in the regime of quantum phase slips.

, the magnitude is large and shape is saw-tooth (Fig. 1, dashed lines)19,20,22. While in ‘thin’ samples the quantum fluctuations should degenerate the PC oscillations into smooth sine-type pattern with much smaller magnitude and strictly one flux periodicity (Fig. 1, dotted lines)13,11. For straightforwardness of interpretation the outlined scenario assumes that both the thick and the thin samples are homogeneous metallic loops containing no weak links. However, it should be noted that for high transparency barriers between the superconducting grains the model13, developed for a loop formed by a chain of weak links, converges to the homogeneous (metallic) loop model11. The observation naturally eliminates the distinction between a chain of weak links and a homogeneous superconducting channel in the regime of quantum phase slips.

To test these hypotheses all-superconducting nanostructures with the loop-shaped central electrode (Fig. 2) were fabricated (for details, see Methods). In zero magnetic field all structures demonstrated conventional Itun(V) dependencies typical for a S1-I-S2-I-S1 tunnel structure. Text-book fits enable determination of the tunnel resistance, the intrinsic deparing energy  and the effective electron temperature Te (typically ∼70 mK at a base temperature ∼50 mK). With the bias voltage V fixed below the gap edge

and the effective electron temperature Te (typically ∼70 mK at a base temperature ∼50 mK). With the bias voltage V fixed below the gap edge  perpendicular magnetic field was slowly swept and the tunnel current was measured Itun(V = const, B).

perpendicular magnetic field was slowly swept and the tunnel current was measured Itun(V = const, B).

All ‘thick’ structures showed pronounced saw-tooth tunnel current oscillations with period  in a full accordance with the earlier findings22 and the model23 (Fig. 3a). The simulated flux dependencies of the tunnel current Itun, superconducting order parameter Δ and gap G, deparing parameter Γ and PC Is are presented in Fig. 3 main panel, left and right insets, respectively. As for these ‘thick’ samples the experimental Itun(V = const, B) dependencies demonstrate constant period, one may conclude that the instrumental-related flux noise is negligible and the spontaneous phase slips can be disregarded. The large period of oscillations corresponds to the condition when the flux-dependent superconducting gap equals the thermal energy

in a full accordance with the earlier findings22 and the model23 (Fig. 3a). The simulated flux dependencies of the tunnel current Itun, superconducting order parameter Δ and gap G, deparing parameter Γ and PC Is are presented in Fig. 3 main panel, left and right insets, respectively. As for these ‘thick’ samples the experimental Itun(V = const, B) dependencies demonstrate constant period, one may conclude that the instrumental-related flux noise is negligible and the spontaneous phase slips can be disregarded. The large period of oscillations corresponds to the condition when the flux-dependent superconducting gap equals the thermal energy  (Eq. (1)) (Fig. 3a, left inset). Due to the strong current dependence of the deparing parameter

(Eq. (1)) (Fig. 3a, left inset). Due to the strong current dependence of the deparing parameter  21 at low temperatures

21 at low temperatures  the above condition is quantitatively almost indistinguishable from the complete suppression of superconductivity

the above condition is quantitatively almost indistinguishable from the complete suppression of superconductivity  . The flux dependence of the PC is strictly saw-tooth with the transition to a new quantum state n (‘vorticity’) very close to the critical value

. The flux dependence of the PC is strictly saw-tooth with the transition to a new quantum state n (‘vorticity’) very close to the critical value  (Fig. 3a, right inset). Better quantitative agreement between the experimental and simulated Itun(Φ)’s can be achieved taking into consideration the monotonous reduction of the superconducting gap Δ(B) by magnetic field (noticeable in Fig. 3a) and the solid state heating/cooling phenomenon24,25. However, we found the improvement of the fits marginal and being not very important for the main subject of the paper.

(Fig. 3a, right inset). Better quantitative agreement between the experimental and simulated Itun(Φ)’s can be achieved taking into consideration the monotonous reduction of the superconducting gap Δ(B) by magnetic field (noticeable in Fig. 3a) and the solid state heating/cooling phenomenon24,25. However, we found the improvement of the fits marginal and being not very important for the main subject of the paper.

All studied structures, including the ones with the thickest loops, can be considered as quasi-one-dimensional:  , with ξ being the superconducting coherence length. The observation enables utilization of the phase slip concept strictly relevant only for a 1D system. In the ‘classical’ limit

, with ξ being the superconducting coherence length. The observation enables utilization of the phase slip concept strictly relevant only for a 1D system. In the ‘classical’ limit  the reduction of the wire cross section σ does not alter the period of oscillations given the structures are sufficiently ‘thick’. However, below a certain threshold,

the reduction of the wire cross section σ does not alter the period of oscillations given the structures are sufficiently ‘thick’. However, below a certain threshold,  and

and  , the magnitude and the period of oscillations rapidly drop demonstrating the saw-tooth pattern with variable period (Fig. 3b). As the flux noise was not providing a noticeable contribution for thicker samples, it is reasonable to assume that the observed variable period for thinner structures is related to some intrinsic size-dependent mechanism of stochastic nature – e.g. thermodynamic fluctuations. Further σ reduction degenerates the oscillations into a smooth quasi-sinusoidal pattern with significantly reduced magnitude (Fig. 3c and Fig. 4) and the period

, the magnitude and the period of oscillations rapidly drop demonstrating the saw-tooth pattern with variable period (Fig. 3b). As the flux noise was not providing a noticeable contribution for thicker samples, it is reasonable to assume that the observed variable period for thinner structures is related to some intrinsic size-dependent mechanism of stochastic nature – e.g. thermodynamic fluctuations. Further σ reduction degenerates the oscillations into a smooth quasi-sinusoidal pattern with significantly reduced magnitude (Fig. 3c and Fig. 4) and the period  . Note that SEM/AFM analysis did not reveal any breaks or/and pronounced constrictions. The I(V, B = 0) dependencies of all samples, including the thinnest ones, did show-up conventional behavior typical for a S1-I-S2-I-S1 tunnel structure. Peculiarities which could be associated with formation of additional junction(s) (e.g. S2’-I-S2’’) were detected neither in the original, nor in the ion milled samples. No hysteresis on I(V, B = 0) characteristics was observed supporting the absence of overheating and the low-invasiveness of the employed tunneling method: the characteristic tunnel current is below 10−10 A (Fig. 4), while the corresponding critical current in nanowires with similar diameters is about 10−7 to 10−6 A26.

. Note that SEM/AFM analysis did not reveal any breaks or/and pronounced constrictions. The I(V, B = 0) dependencies of all samples, including the thinnest ones, did show-up conventional behavior typical for a S1-I-S2-I-S1 tunnel structure. Peculiarities which could be associated with formation of additional junction(s) (e.g. S2’-I-S2’’) were detected neither in the original, nor in the ion milled samples. No hysteresis on I(V, B = 0) characteristics was observed supporting the absence of overheating and the low-invasiveness of the employed tunneling method: the characteristic tunnel current is below 10−10 A (Fig. 4), while the corresponding critical current in nanowires with similar diameters is about 10−7 to 10−6 A26.

Discussion

One can interpret the results assuming that below the threshold cross section σq either (i) coupling of the system to external disturbance increases; or (ii) sample imperfections (revealed hidden intrinsic and/or generated by sample processing) qualitatively change the properties of the system; or (iii) an intrinsic size phenomenon develops.

First option looks rather improbable as coupling of a nanoloop, isolated by the pair of high-Ohmic tunnel contacts S1-I-S2, should not depend on the wire cross section σ. Certainly, the employed method of low energetic ion beam milling slightly reduces the area of the probing tunnel junctions27,28 leading to the increase of the tunnel resistance. However, the effect is small and by no means can explain the hypothetical increase of the coupling of the sample to the noisy external environment below the threshold σq.

Second alternative (sample imperfections) has been given the highest attention. An interpretation based on formation of a weak link – Josephson junction (JJ) – between the strong (massive) superconducting arms of the loop (SQUID-type structure) or a chain of JJs is not credible. First, an extensive SEM/AFM analysis revealed no suspicious sections to be considered as potential weak links with the local critical current density much smaller than in the rest of the loop (Fig. 2). Here we would like to emphasize the importance of titanium data (Fig. 4): the cross sections of the loops are so ‘huge’ (σ1/2∼ 60 nm) and the surface roughness, measured by AFM, is so small (±2 nm, Fig. 2d, inset) that the existence of a hypothetical JJ is rather unrealistic. The nanostructures were fabricated and processed using the same technique as the nanowires, where an extensive microscopic and elemental analysis confirmed their homogeneity down to significantly smaller cross sections12. Second, if occasionally such a hypothetic JJ is formed, the properties of such a system would be unique depending on the particular values of the charging and Josephson energy of that junction. However, the results are well reproduced on samples with close values of the diameter of the wire forming the loop. The observation supports the conjecture that our results deal with a universal size effect, rather than with accidentally formed JJs with random parameters. Third, if at least a pair of S2’-I-S2’’ junctions (one, in each arm of the loop) and/or an extra single tunnel junction in the pole region are formed, then the existence of that extra junction(s) should manifest itself as an appearance of a certain peculiarity on the I-V characteristic, which has never been the case. Fourth, even if an undetectable hypothetical weak link is formed, the amplitude of the experimentally measured tunnel current oscillations would be infinitely small. The employed method is based on measuring the tunnel current within the locus of the probing tunnel junction. The oscillating in the loop PC, periodically reaching sub-critical values, modulates the DOS leading to the corresponding oscillations of the tunnel current. Thus the method can provide a decent sensitivity only in the case of a relatively homogeneous loop with the uniform current density including the regions of the tunnel probes. Due to the employed fabrication method (multi-angle metal evaporation followed by lift-off lithography) in our samples the regions close to the tunnel probes (‘poles’) are always slightly wider than the thinner ‘equatorial’ parts of the loop (Fig. 2), where the probability of formation of a weak link (e.g. constriction) is higher. If the case, within the locus of the tunnel probe the oscillations of the DOS and the corresponding tunnel current would be negligible being insensitive to the modulation of the local current Isprobe by the much smaller critical current of a (remote) weak link  . Summarizing, the JJ scenario cannot explain the gradual reduction of the period and the magnitude of the tunnel current oscillations with reduction of the wire cross section (Fig. 3 and 4). As soon as inside the loop a single JJ with much smaller local critical current is formed, the amplitude of the tunnel current oscillations would drop to undetectably small values.

. Summarizing, the JJ scenario cannot explain the gradual reduction of the period and the magnitude of the tunnel current oscillations with reduction of the wire cross section (Fig. 3 and 4). As soon as inside the loop a single JJ with much smaller local critical current is formed, the amplitude of the tunnel current oscillations would drop to undetectably small values.

The third option – intrinsic size-dependent disturbance  – looks mostly intriguing. Contribution of thermal fluctuations1,2 can be neglected at temperatures

– looks mostly intriguing. Contribution of thermal fluctuations1,2 can be neglected at temperatures  29. Though the corresponding model1,2 is not applicable to the ultra-low temperatures of the experiment, one may argue that qualitatively thermal fluctuations should be taken into consideration when the flux-dependent superconducting gap is of the order of the thermal energy

29. Though the corresponding model1,2 is not applicable to the ultra-low temperatures of the experiment, one may argue that qualitatively thermal fluctuations should be taken into consideration when the flux-dependent superconducting gap is of the order of the thermal energy  . Due to the very sharp G(Φ) dependence (Fig. 3a, left inset) the correction might be important only within the very vicinity of the transition to a new quantum state: the very ‘tips’ of the saw-tooth Is(Φ) and Itun(Φ) oscillations. By no means the thermal fluctuations could explain even qualitatively the changes in the shape, the magnitude and the period of Itun(Φ) oscillations with the reduction of the loop cross section σ (Figs. 3 and 4). Various mesoscopic fluctuations30,31 may reduce the local potential barrier quenching formation of the metastable states responsible for the large period oscillations, while applicability of these models to the experiment is not clear.

. Due to the very sharp G(Φ) dependence (Fig. 3a, left inset) the correction might be important only within the very vicinity of the transition to a new quantum state: the very ‘tips’ of the saw-tooth Is(Φ) and Itun(Φ) oscillations. By no means the thermal fluctuations could explain even qualitatively the changes in the shape, the magnitude and the period of Itun(Φ) oscillations with the reduction of the loop cross section σ (Figs. 3 and 4). Various mesoscopic fluctuations30,31 may reduce the local potential barrier quenching formation of the metastable states responsible for the large period oscillations, while applicability of these models to the experiment is not clear.

On the contrary, the recent models considering quantum fluctuations in superconducting nanorings13,11 seem to be quite relevant. Whether the loop is homogeneous11, or consists of weakly coupled superconducting grains13 - both models predict the same dependencies En(Φ) and Is(Φ) (Fig. 1, dotted lines). However, as discussed above, in case of weak links13 the tunnel current oscillations Itun(Φ) would not be experimentally resolved. We do not have any experimental evidence that the loops in our structures can be considered as 1D chains of JJs with the local critical current significantly lower than in the rest (metallic) part of the loop. The studied samples do not have an ideal (atomically flat) surface, but they are smooth enough to be considered as homogeneous metallic loops with the variation of the diameter below ± 3 nm. Quantum fluctuation scenario is particularly intriguing as the σq1/2 threshold values correspond to the diameters where the broadening of R(T) dependencies has been associated with quantum phase slip effect in aluminium9,10 and titanium12 nanowires. Simulations based on QPS model provide reasonable quantitative agreement with experiment (Figs. 3c and 4). Dependence (4) inevitably results in doubling of the tunnel current oscillation period (Figs. 3c and 4, solid curves). The fine structure was not clearly resolved in experiment: in the QPS limit the Itun(Φ) oscillation magnitude exponentially drops with decrease of the wire cross section σ11 burying the oscillation pattern below the experimental noise ∼10−13 A. Nevertheless the very observation of the smooth sine-type Itun(Φ) oscillations with significantly reduced magnitude and period ΔΦ/Φ0 = 1 on the same structures, which at larger cross sections σ demonstrated qualitatively different oscillation pattern, supports the particular size dependent scenario – quantum fluctuations. Here we would like to emphasize once again that the concern about sample homogeneity with respect to interpretation of our data based on QPS scenario is superfluous, how it has been explicitly shown in the recent theoretical analysis32.

To summarize, we demonstrated that in superconducting aluminum and titanium loop-shaped tunnel nanostructures the period, the magnitude and the shape of tunnel current oscillations are dramatically modified below a certain cross section of the wire forming the loop. The comprehensive evaluation of the data leads to the conclusion that a simple interpretation based on sample inhomogeneity is not supported by microscopic and elemental analysis of the samples, and, what is even more important, has a deficiency in explaining the gradual reduction of the period and the magnitude of the oscillations with reduction of the characteristic dimension (cross section of the wire forming the loop). Alternative scenarios based on thermal fluctuations and/or unusual size-dependent coupling of the samples to external noisy environment are not credible. In our opinion, the most plausible interpretation of the results is related to the essentially size-dependent nanoscale phenomenon - quantum phase slips, suppressing the persistent currents in the ultra-narrow loops. The interpretation is not improbable as the evidence of QPS has been reported in a number of independent experiments on nanowires of similar dimensions and there are no obvious reasons why the same mechanism should be absent in nanorings. The effect is of fundamental importance for quantum solid state physics in general and superconductivity - in particular. To our best knowledge, the discovery is the first experimental observation of the impact of quantum fluctuations on the ground state of a macroscopically coherent system. Additionally to the basic science importance, the emerging new physics is expected to result in intriguing applications: quantum standard of electric current33 and qbit34,35 and single election transistor36.

Methods

The samples were fabricated using electron beam lithography followed by the ultra-high vacuum deposition of the metals and the lift-off technique. The double-junction geometry was used to eliminate the undesired contribution of quasiparticles and to make the measurements less invasive compared to a single-junction N-I-S configuration22. The oval shape of the loop electrode was selected to eliminate parasitic overlapping shadows emerging in two-angle metal evaporation process. In earlier samples the loop contained ‘ears’ at the poles with tunnel junctions (Fig. 2a), while in later designs the loop overlapped the contacts (Fig. 2b).

Contacts (S1) were made of aluminum oxidized in vacuum forming tunnel barriers (I), for the loop (S2) we utilized either aluminum, or titanium. Both materials have already demonstrated non-vanishing contribution of quantum fluctuations deduced from the broadened R(T) dependencies9,10,12. Low energetic Ar+ ion beam milling27,28 was used to gradually and non-invasively reduce the nanostructure line cross section σ enabling experimental study of a size-dependent phenomenon. Utilization of Ar+ ions at acceleration voltages ≤ 1 keV can be considered as virtually introducing no defects as the ion penetration depth ∼ 2 nm is comparable to the thickness of the naturally grown oxide. Additionally, the sputtering provides polishing effect eroding small scale imperfections of the lift-off fabricated nanostructures9,10,12.

The dimensions of the fabricated samples were measured with atomic force (AFM) and scanning electron (SEM) microscopes. However the AFM/SEM study after each sputtering would pose a too high threat of damaging the extremely fragile structures. In practice, the AFM/SEM measurements were taken after the first (high dose) sputtering step and finally at the end of the last measuring session. The sample dimensions at the intermediate steps were defined by interpolation of the known initial and final AFM/SEM data. The method results in high relative errors in determination of the average cross section of the line forming the loop. According to our previous studies of aluminium and titanium nanowires9,10,12 enabling independent determination of their cross section from the normal state resistance, after multiple sessions of ion beam sputtering the sample diameter can be specified with accuracy better than ± 3 nm. The large error in determination of the diameter of the wire forming the loop in tunnel nanostructures comes mainly from the uncertainty in defining the interface between the metal and the sputtered substrate and not the actual roughness (variation of the cross section) for a given sample (see Fig. 2d, inset).

High resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis revealed the expected non-single-crystalline structure of the samples. The grains were compactly packed with inevitable dislocations and associated stacking faults (Fig. 2c). However, no signature of any sort of inclusions (e.g. foreign material clusters) or distortion due to ion implantation in the ion milled samples was found. Elemental analysis of samples, fabricated using the same vacuum chamber as in present work, revealed the highest concentration of foreign elements inside the metal matrix being associated with 0.3 at. % of oxygen12. The high-resolution TEM images of samples from the present paper and wide 2D films and nanowires, fabricated under the same conditions, were indistinguishable between themselves and what is even more important – indistinguishable before and after the ion milling. The observation supports the statement that the utilized reduction of the cross section of the nanowire forming the loop by low energy ion milling cannot introduce any structural defects12.

After each step of reducing the cross section, the samples were cooled down to temperatures well below the critical temperature of aluminium and/or titanium using He3/He4 dilution refrigerator. The measurements were performed inside electromagnetically shielded room using battery powered front-end amplifiers and carefully filtered input/output lines. The actual effective electron temperature Te was determined by fitting the zero-field Itun(V,B = 0) dependence with the familiar text-book expression. Four-stage RF filtering enabled us to keep the increase of the electron temperature  mK above the base temperature of the refrigerator Tbath37. The tunnel current Itun over the whole structure was measured as function of perpendicular magnetic field intensity at several chosen constant bias voltages. The magnetic field sweeps (covering typically 5 to 10 periods of the oscillations) ranged from few up to ∼ 40 minutes. The majority of the experiments were made at temperatures between 50 mK and 150 mK, where neither the sweep rate, nor the temperature dependent effects were observed.

mK above the base temperature of the refrigerator Tbath37. The tunnel current Itun over the whole structure was measured as function of perpendicular magnetic field intensity at several chosen constant bias voltages. The magnetic field sweeps (covering typically 5 to 10 periods of the oscillations) ranged from few up to ∼ 40 minutes. The majority of the experiments were made at temperatures between 50 mK and 150 mK, where neither the sweep rate, nor the temperature dependent effects were observed.

The effective area of the loop electrode calculated from the periodicity was found to vary from a cool down to another one less than 0.5 %, which is of the same order as within a single measurement session. The difference between the calculated effective area and the one measured from SEM/AFM analysis was found to be also about 0.5 %. The error in defining the magnetic field due to sample/coil misalignment was estimated to be about 0.05 %, hence being smaller than the above indicated uncertainties.

References

Langer, J. S. & Ambegaokar, V. Intrinsic resistive transition in narrow superconducting channels. Phys. Rev. 164, 498–510 (1967).

McCumber, D. E. & Halperin, B. I. Time scale of intrinsic resistive fluctuations in thin superconducting wires. Phys. Rev. B 1, 1054–1070 (1970).

Lukens, J. E., Warburton, R. J. & Webb, W. W. Onset of Quantized Thermal Fluctuations in "One-Dimensional" Superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 25, 1180–1184 (1970).

Newbower, R. S., Beasley, M. R. & Tinkham, M. Fluctuation Effects on the Superconducting Transition of Tin Whisker Crystals. Phys. Rev. B 5, 864–868 (1972).

Zaikin, A. D., Golubev, D. S., van Otterlo, A. & Zimanyi, G. T. Quantum Phase Slips and Transport in Ultrathin Superconducting Wires. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1552–1555 (1997).

Golubev, D. S. & Zaikin, A. D. Quantum tunneling of the order parameter in superconducting nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 64, 014504-1 – 014504–14 (2001).

Giordano, N. Evidence for macroscopic quantum tunneling in one-dimensional superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2137–2140 (1988).

Bezryadin, A., Lau, C. N. & Tinkham, M. Quantum suppression of superconductivity in ultrathin nanowires. Nature 404, 971–974 (2000).

Zgirski, M., Riikonen, K.-P., Touboltsev, V. & Arutyunov, K. Yu. Size dependent breakdown of superconductivity in ultranarrow nanowires. Nano Lett. 5, 1029–1033 (2005).

Zgirski, M., Riikonen, K.-P., Touboltsev, V. & Arutyunov, K. Yu. Quantum fluctuations in ultranarrow superconducting aluminum nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 77, 054508-1 - 054508-6 (2008).

Arutyunov, K. Yu., Golubev, D. S. & Zaikin, A. D. Superconductivity in one dimension. Phys. Rep. 464, 1–70 (2008).

Lehtinen, J. S., Sajavaara, T., Arutyunov, K. & Vasiliev, A. Evidence of quantum phase slip effect in titanium nanowires, arXiv:1106.3852v1 (2011).

Matveev, K. A., Larkin, A. I. & Glazman, L. I. Persistent current in superconducting nanorings. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 096802-1–096802-4 (2002).

Koshnick, N. C., Bluhm, H., Huber, M. E. & Moler, K. A. Fluctuation Superconductivity in Mesoscopic Aluminum Rings., Science 318, 1440–1443(2007).

Bert, J. A., Koshnick, N. C., Bluhm, H. & Moler, K. A. Fluxoid fluctuations in mesoscopic superconducting rings. Phys. Rev. B. 84, 134523 (2011).

Berger, J. Influence of Thermal Fluctuations on Uniform and Nonuniform Superconducting Rings according to the Ginzburg-Landau and the Kramer-Watts-Tobin Models. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 23, 225701 (1962).

Bluhm, H., Koshnick, N. C., Huber, M. E. & Moler, K. A. Magnetic response of mesoscopic superconducting rings with two order parameters, Phys. Rev. Let 97, 237002–237005 (2006).

Little, W. A. & Parks, R. D. Observation of quantum periodicity in the transition temperature of a superconducting cylinder. Phys. Rev. Lett. 9, 9–12 (1962).

Pedersen, S., Kofod, G. R., Hollingbery, J. C., Sørensen, C. B. & Lindelof, P. E. Dilation of the giant vortex state in a mesoscopic superconducting loop. Phys. Rev. B 64, 104522-1-104522-4 (2001).

Vodolazov, D. Y., Peeters, F. M., Dubonos, S. V. & Geim, A. K. Multiple flux jumps and irreversible behavior of thin Al superconducting rings. Phys. Rev. B 67, 054506-1-054506-6 (2003).

Anthore, A., Pothier, H. & Esteve, D. Density of States in a Superconductor Carrying a Supercurrent. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 127001–127005 (2003).

Arutyunov, K. Yu. & Hongisto, T. T. Normal-metal-superconductor interferometer. Phys. Rev. B 70, 064514-1-064514-6 (2004).

Vodolazov, D. Y., Peeters, F. M., Hongisto, T. T. & Arutyunov, K. Yu. Microscopic model for multiple flux transitions in mesoscopic superconducting loops. Europhys. Lett. 75 (2), 315–320 (2006).

Giazotto, F., Heikkilä, T. T., Luukanen, A., Savin, A. M. & Pekola, J. P. Opportunities for mesoscopics in thermometry and refrigeration: Physics and applications, Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 217–274 (2006)

Tirelli, S., Savin, A. M., Pascual Garcia, C., Pekola, J. P., Beltram, F. & Giazotto, F. Manipulation and Generation of Supercurrent in Out-of-Equilibrium Josephson Tunnel Nanojunctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 077004-1–0777004-4 (2008).

Peng Li Wu, P. M., Bomze, Y. Borzenets, I. V. Finkelstein, G. & Chang, A. M. Retrapping current, self-heating and hysteretic current-voltage characteristics in ultranarrow superconducting aluminum nanowires, Phys. Rev. B 84, 184508 (2011).

Savolainen, M., Touboltsev, V., Koppinen, P., Riikonen, K.-P. & Arutyunov, K. Yu. Ion beam sputtering for progressive reduction of nanostructures dimensions. Appl. Phys. A 79, 1769–1773 (2004).

Zgirski, M., Riikonen, K.-P., Tuboltsev, V., Jalkanen, P., Hongisto, T. T. & Arutyunov, K. Yu. Ion beam shaping and downsizing of nanostructures. Nanotechnology 19, 055301-1–055301-6 (2008).

Zgirski, M. & Arutyunov, K. Yu. Experimental limits of the observation of thermally activated phase-slip mechanism in superconducting nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 75, 172509-1–172509 -4 (2007).

Oreg, Y. & Finkel’stein, A. M. Suppression of Tc in Superconducting Amorphous Wires. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 191–194 (1999).

Zhou, F. & Spivak, B. Superconducting Glass State in Disordered Thin Films in a Parallel Magnetic Field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 5647–5650 (1998).

Vanevic, M. & Nazarov, Yu. V. Quantum phase slips in superconducting wires with weak links., arXiv:1108.3553 (2011)

Mooij, J. E. & Nazarov, Yu. V. Superconducting nanowires as quantum phase-slip junctions. Nature Physics 2, 169–172 (2006).

Mooij, J. E. & Harmans, C. J. P. M. Phase-slip flux qubits. New J. Phys. 7, 219-1–219-7 (2005).

Astafiev, O. V. Coherent quantum phase slip.. Nature in press (2012).

Hongisto, T. T. & Zorin, A. A. Single-charge transistor based on the charge-phase duality of a superconducting nanowire circuit. Phys. Rev. Lett in press (2012).

Arutyunov, K. Yu., Auraneva, H.-P. & Vasenko, A. S. Spatially resolved measurements of nonequlibrium quasiparticle relaxation in superconducting aluminium, Phys. Rev. B 83, 104509-1–104509-7 (2011).

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to acknowledge O. Astafiev, F. Hekking, Y. Nazarov, T. Klapwijk, D. Vodolazov, A. Zaikin and A. Zorin for valuable discussions; M. Zgirski and P. Jalkanen for assistance with ion beam treatment. The work was supported by the Finnish Academy project FUNANO, Finnish Technical Academy project DEMAPP and Ministry of Science and Education of Russian Federation grant 2010-1.5-508-005-037.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.T.H. designed and fabricated the structures, performed experiments and analyzed the data. J.S.L. fabricated structures and participated in measurements. L.I.L. made AFM analysis. A.L.V. contributed with TEM analysis. K.Yu.A. planned the project, made numerical simulations and interpreted the results.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareALike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Arutyunov, K., Hongisto, T., Lehtinen, J. et al. Quantum phase slip phenomenon in ultra-narrow superconducting nanorings. Sci Rep 2, 293 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00293

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00293

This article is cited by

-

Superconducting insulators and localization of Cooper pairs

Communications Physics (2021)

-

Superconducting fluctuation induced conductance corrections near a pair-breaking quantum phase transition in doubly connected ultrathin cylinders of Al

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2020)

-

Hybrid rf SQUID qubit based on high kinetic inductance

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Quantum size phenomena in single-crystalline bismuth nanostructures

npj Quantum Materials (2017)

-

Quantum Fluctuations of a Superconductor Order Parameter

Nanoscale Research Letters (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.