Key Points

-

Gives an overview of dental corporates in the US and Australia.

-

Provides details of the benefits and harms brought by dental corporates in the US.

-

Provides information on the current UK dental landscape regarding dental corporates.

Abstract

The UK government opened NHS dentistry to competition in 2006. By 2015–2016 just over three quarters of NHS contracts were held by non-corporate providers with corporate contracts, on average, having a lower £:UDA (unit of dental activity) value and higher UDA targets than non-corporate contracts. The corporate market share continues to expand through inorganic and organic growth and new financial backers are entering the arena. It is not known how these changes will affect the profession though inspiration can be drawn from overseas markets. In this article I aim to provide an overview of the dental corporate market in the USA and Australia as well as some insight as to how the sector stands in England.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

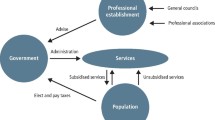

In the UK, corporate providers operate in care sectors including pharmacy and social care with consolidation and corporate growth bringing changes to these areas and professions. Some changes are positive but there are accusations that corporate entry and/or growth has reduced professional autonomy, is leading to increasingly deskilled professions and, in some cases, affecting patient services.1,2,3,4 While the cost of services may be reduced in an open market, competition between providers to win contracts on a lowest-cost basis has, in some instances, driven down the quality of care to the 'minimum quality level allowed' with it being acknowledged that the system 'incentivises poor care, low wages and neglect, often acting with little regard for the people it is supposed to be looking after'.5

Corporatisation of both pharmacy and social care in the UK is arguably more developed than dentistry and looking at these sectors can provide indications as to how corporate investment can affect the dental landscape while looking at dentistry itself could further knowledge. Corporate dentistry is growing in nations including the US and Australia and this paper looks at corporate dentistry in these countries. The corporate dental field in the US is more mature, and therefore has been more widely examined, while recent legislation (2010) provided opportunities for non-dentists and/or corporate entities to own dental practices in Australia6 making their market less developed.

This paper is the second in a series aimed at providing context and developing an understanding of dental corporates and their impact on UK dentistry. The first in the series examined the development of DBCs in the UK and the role played by the BDA. This paper reviews the corporate market abroad and in the UK and is one of the few papers reviewing the corporate dental markets.

The United States

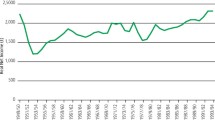

In the early 1990s, 91% of dentists in the US owned or shared ownership of their practice with 67% of dentists being solo practitioners. By 2012 the percentage of owner practitioners had fallen to 84.8% and that of solo practitioners to 57.5%. In 2007 the number of dental sites controlled by multiunit dental companies increased by 49.0% to 8,442 with the number of offices being controlled by firms who own more than ten practices increasing by 2,852 between 1992 and 2007 (Fig. 1).7 Some economists expect corporate dentistry to continue to grow, others predict that the market share has plateaued, or will reach a plateau, at or about 20–25%.8

Drivers of the increase in corporate dentistry in the US include economic and social aspects8 with influencing factors including the priorities of dental graduates, legislation and the corporates themselves. A combination of financial constraints, a fall in the utilisation of oral healthcare and inadequate government reimbursement has challenged existing dental practices and made it increasingly difficult for recent dental graduates to find employment with them. Dental management companies (DMCs), and other similarly termed entities, have identified an opportunity and offer business models designed to allow dentists to earn while providing care to various population groups. This model is broadly referred to as corporate dentistry.8 In the US the term corporate dentistry does not have universal meaning and refers to a variety of practice modalities where management services are provided. In many cases dentistry practice services are provided by a third party organisation funded by for-profit investors that are not directly engaged in clinical dental practice or dentists. The involvement of a DMC can vary from providing or administering management services to, in practice, owning the clinics and having complete control over operations including clinical aspects.8,9,10 The latter has been highlighted as a problem as many American states do not allow dentistry to be practised by a non-dentist and the legislation covering this also prohibits a non-dentist corporation from receiving fees for providing dental services that are in the scope of practice of a licenced dentist.8,9 For profit entities backing dental chains in the US include Morgan Stanley (Big Smiles), Valor Equity Partners (All Smiles) and Friedman Fleischer & Lowe (Kool Smiles).11

A report published in 2013 notes access to dental care is a problem in certain areas of the US and there is a shortage of dentists, problems that if not corrected will get worse, furthermore it is noted that if dental corporates did not employ dentists to provide care, for example, to those on the Medicaid (tax funded) programme they would go untreated.9 The latter is echoed by a 2011 study covering Texas Medicaid patients that found dental corporates are providing dental care to some of the poorest, most underserved populations promptly and at a relatively lower cost when compared to traditional practices.10 The use of scale on aspects of the day-to-day business enable managed practices to operate with much lower costs than traditional dental practices leading to Medicaid patients being serviced at a profit. However, questions have been raised as to the impact on care quality with evidence that dental corporates exert pressure on practices to provide expensive and sometimes unnecessary care especially for those receiving state funded care.9 Official investigations into the operation of some corporate dental organisations have been carried out with the influence of private equity being discussed.9

One such investigation, aided by whistleblowing in 2011, by the US Senate investigated allegations of abusive treatment of children in clinics controlled by corporate investors rather than dentists and published a report in 2013.9 The report, while recognising the value of venture capital and private equity as being central to economic growth and innovation, questioned their place in tax-funded dental practice and noted their targeting of this sector as being alarming. The report raised the question of why private equity would invest capital in a business model that cannot afford to take Medicaid patients because of low reimbursement rates. The report questions how money can be made and, in contrast to a study carried out by an economic research and consulting firm,10 suggests this is due to 'volume' – the number of patients that are seen – and practices such as overbooking and bonuses to incentivise both dentist and non-dentists employees, to maximise volume and therefore profit. Also highlighted was the fundamentally deceptive ownership structure used by some DMCs that rendered the 'owner dentist' to an owner in name only. A more detailed overview of the US Senate report prepared by the Staff of the Committee on Finance and Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate is given via a case study of Small Smiles Dental Centres (Box 1).9,11,12,13,14

Australia

The formation of corporates and their consolidation and operation of dental practices in Australia is relatively new as initially the area was not an attractive target for corporatisation due to being too capital intensive and reliant on a short supply of skilled labour.15 In 2012 there were five main groups actively acquiring and/or establishing practices – Primary Dental, Pacific Smiles Group, 1300 Smiles, Lumino The Dentists and Dental Corporation (the largest operator).15,16 Similar to the US, corporates operate under different business models that have changed over the years and in some cases there has been, essentially, a change of ownership.15 The objective of some DBCs is to improve efficiencies and cut costs through centralised administration, training, human resources, database of patients and a single patient contact centre, resulting in higher administration fees of 6–8%, while others allow practices to run themselves resulting in administrative fees of less than 4%.17 In terms of payment for buying a practice there are also variations, for example some DBCs pay the vendor a proportion up front and the remainder later, for example in a year or five years, as long as the practice maintains results with quicker handovers giving less time for clawback should a practice not reach its targets.17 In 2014 10% of practices had joined one of the corporate groups.16

Dentists have cited a better work life balance as an attraction to working within a corporate as well as equipment investment.16 However, not all practitioners agree and others have stressed the benefits of non-corporate practice and the way in which relationships are built up with patients.16 Selling a practice to a corporate can be an opportunity to achieve a high value for the practice and shares that could increase in value with the success of the corporate.15 The Australian Dental Association believe there is a potential conflict of interest between the responsibilities held by a dentist and the corporate owners of dental practices. The need to provide financial returns to shareholders has the potential to compromise the ethical standards and ability to practise patient-centred dentistry of an individual dentist and additionally there is a risk of shareholders' and owners' equity being placed above patient need.6

The success of corporate dental practices in Australia so far has largely been due to the dental practitioners they employ on a salary equivalent to those in private practice. Additionally, dentists were involved in setting up all of the 'big five' dental corporates and appreciated the importance of the workforce for success. Generally, corporates have sought to keep the services of the outgoing practice owner for the transition of goodwill and profitability and to help blend the practice into the corporate.17 However, the viability of corporate dentistry can only be evidenced once acquisition has slowed, first generation practice owners have left and the business has become operationally mature.15 Once corporate management has evolved from the original owners and companies look to increase shareholder value, the growing pool of young, inexperienced graduates may be a tempting solution to cut costs.15

One of the founders of Pacific Smiles Group (the first dental corporate in Australia) has discussed why a corporate would consolidate, corporatise or accumulate practices – profit.15 Heads of corporations always have the principal aim to 'increase shareholder value' and the contrast between this and the principal aim of a dentist will always be contentious in the delivery of healthcare services. Dental corporations believe they can buy a practice and make a profit. How services of the resulting corporation are delivered is essentially a side issue.15

Dental market in England

General practice-based dental care in the UK, both private and NHS, is largely provided by independent practitioners. In December 2015, 10,283 locations were registered with the CQC (England) as being in the primary dental care sector.18

NHS dental care

NHS primary care organisations (PCOs) contract with general dental practices to provide NHS dental care, a provider must hold an NHS contract that can, in certain circumstances, be tendered for.19 In England, for the 2016/17 financial year, there were approximately 8,900 NHS contracts worth in the region of £2.8 billion (the sum of all payments due under the contract).

Corporate dentistry sector

A dental corporate can be defined as an incorporated company but for the purposes of this series of papers the term dental corporate will include a sole trader/partnership operating three or more dental practices. In 2015, the corporate dentistry sector in England was estimated to consist of over 200 dental groups with nearly 2,000 practices.18 Corporates provide both NHS and private care with most corporate providers operating on a small scale, local level with three or four practices. NHS corporate dentistry in England alone has a contract value of £1.3 billion (October 2015). The market has been consolidating since the 1990s, both in terms of the market as a whole and the major providers within it, with DBCs growing through inorganic and organic growth.20

The growth of the corporate sector brings with it concerns. These include the rationalisation of the profession in order for corporate providers to operate economically, efficiently and competitively.21,22,23 One contributor to this is standardisation that includes following protocols and procedures for service uniformity. Rationalisation can improve service, for example, in pharmacy rationalisation allows for a quick service preferred by some users24 with pharmacists, in theory, able to concentrate on pharmacy services and health-related issues.25,26 Downsides to standardising include preclusion of autonomy,2,21,22 with, for example, a limited choice of materials and consumables, dehumanising staff and customers and potential deprofessionalisation.22,23,27,28

Additionally, if the commercial owner of a dental clinic is also a private health insurer providing insurance for dental services, the conflicts of interest that are commonly raised in regards to healthcare, which can relate to economic aspects as well as patient and clinician autonomy,29 could be compounded.

There are a number of larger corporates in the UK with ten, in England in June 2015, holding more than 20 high street practices (Table 1). Rough estimates for those holding less than 20 practices, in England at the same point in time, are: 119 hold three practices, 28 hold four, 18 hold five, 15 hold six, five hold seven, four hold eight, two hold nine, two hold ten, three hold 11, two hold 12, one holds 13, one holds 17 and one holds 19.18

The practice market

The dentistry market, in terms of practice sales, is strong (2015) with the demand for, and value of, practices high in certain parts of the country, though the prices achieved by some dental practices are more indicative of high demand than the profits that can be achieved.30,31,32 Overall, there is an increasing demand for private practices, possibly due to buyers priced out of the NHS, while the desire for a mixed practice remains strong.30,33 Despite NHS contract uncertainty, the highest value practices are still NHS practices, which continue to outstrip mixed and private practices, though private practice values are gaining ground.34

The practice market continues to consolidate with both Oasis and mydentist being active across the UK.33 Smaller groups, for example those with less than ten practices, are also focusing on growth and are increasingly active. One broker reported selling over £28 million of dental practices over the period of autumn 2014 – autumn 2015.33 For 2015, associates and first time buyers viewed the most practices, followed by independent single practice owners, multiple practice owners with less than ten practices and finally larger multiple owners (more than ten practices).33 There has been a greater demand for private practices and an increase in interest from private equity and investors fuelling the top end of the market and corporates being aggressive in their marketing.30,33 There is an increasing number of dentists looking to buy a practice with buyers outstripping sellers and practice owners being approached by individuals and corporates to see if they would be interested in selling their practice.30,34

The average profit of private dental practices in the UK overtook that of average NHS practices in 2013/14 for the first time in nearly a decade.35 In 2015 an average NHS practice made a profit of £129,265 per principal, compared to £140,129 in a private practice. The gap in profit may be due to private practices having greater control over their income and while costs seemed static private practices saw an increase of more than 8% in fee income between 2014 and 2015 with the NHS equivalent remaining relatively static.36 In 2013/2014, the average gross fee income generated by a private dentist was £248,000, compared to £180,000 for an NHS dentist with practice expenses equating to 65% and 68% of fee income respectively.35

Conclusion

This overview of the dental market in the UK and abroad indicates that the entry of corporate bodies into healthcare has brought some benefits to patients but there have also been problems. In the US, corporates provide dental care to those who would otherwise not receive it in an efficient and relatively inexpensive manner when compared to traditional practices, though their methods have been called into question with one company found to place profit ahead of patient care. The sector, in England, is growing and continues to consolidate.

References

Dobson R T Perepelkin J . Pharmacy ownership in Canada: implications for the authority and autonomy of community pharmacy managers. Res Social Adm Pharm 2011; 7: 347–358.

Jacobs S, Hassell K, Ashcroft D, Johnson S, O'Connor E . Workplace stress in community pharmacies in England: associations with individual, organizational and job characteristics. J Health Serv Res Policy 2014; 19: 27–33.

Grey N J, O'Brien K L . Sad example of profits before patients. Pharm J 2002; 269: 247.

The Pharmaceutical Journal. Tesco stops supply of EHC to under 16s. Pharm J 2002; 269: 121.

The Centre for Health and the Public Interest. The future of the NHS? Lessons from the market in social care in England. 2013. Available at https://chpi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/CHPI-Lessons-from-the-social-care-market-October-2013.pdf (accessed July 2015).

Australian Dental Association Inc. Corporate Ownership. 2014. Available at https://www.ada.org.au/Dental-Professionals/Policies/Third-Parties/5-3-Corporate-Ownership/ADAPolicies_5-3_CorporateOwnership_V1.aspx (accessed August 2018).

Guay A, Warren M, Starkel R, Vujicic M . A Proposed Classification of Dental Group Practices. 2014. Available at http://www.ada.org/∼/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/HPIBrief_0214_2.ashx (accessed November 2015).

Academy of General Dentistry. Investigative Report on the Corporate Practice of Dentistry. 2013. Available at https://www.agd.org/docs/default-source/advocacy-papers/agd-white-paper-investigate-report-on-corporate-dentistry.pdf?sfvrsn=c0d75b1_2 (accessed August 2018).

Joint Staff Report On The Corporate Practice Of Dentistry In The Medicaid Program. (Chairman M Baucus). Washington: U S. Government Printing Office, 2013.

Laffer Associates. Dental Service Organizations: A Comparative Review. 2012. Available at https://www.heartland.org/_template-assets/documents/publications/20120918_2012.09.19dsos.pdf (accessed November 2015).

Hagan, D . Corporate dentistry bleeds Medicaid, vulnerable low-income children. 2015. Available at http://www.insurancefraud.org/article.htm?RecID=3398#.VkH3aunTG70 (accessed December 2015).

McCanne D . Private equity investors moving into dentistry. Physicians for a National Health Program. 2012. Available at http://pnhp.org/blog/2012/05/17/private-equity-investors-moving-into-dentistry/ (accessed July 2015).

United States Senate. Electronic transmission. 2011. Available at https://www.grassley.senate.gov/sites/default/files/about/upload/2011_11_18-CEG-and-Baucus-to-Church-Street-Health-Management.pdf (accessed November 2015).

NBC News. Firm That Manages Dental Clinics for Kids Excluded From Medicaid. 2014. Available at https://www.nbcnews.com/news/investigations/firm-manages-dental-clinics-kidsexcluded-medicaidn50416 (accessed September 2015).

Genna Levitch. Corporatised dentistry 10 years on. 2012. Available at https://www.levitch.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/2012-9-10-Corporates-10yrs.pdf (accessed June 2015).

Bite Magazine. Corporate dentistry. 2014. Available at https://bitemagazine.com.au/corporate-dentistry/ (accessed November 2015).

Bite Magazine. Other people's money. 2013. Available at https://bitemagazine.com.au/other-peoples-money/ (accessed November 2015).

Care Quality Commission. How to get and re-use CQC information and data. 2015. Available at https://www.cqc.org.uk/about-us/transparency/using-cqc-data#directory (accessed various 2015–2017).

British Dental Association. GDS and PDS in England and Wales. 2014. Available at www.bda.org/dentists/advice/ba/Documents/General%20Dental%20Services%20and%20Personal%20Dental%20Services%20in%20England%20and%20Wales%20-%20May%2015.pdf [BDA members only] (accessed August 2018).

Laing & Buisson. Dentistry UK Market Report 2014. London: LaingBuisson, 2014.

Harding H, Taylor K . The McDonaldisation of pharmacy. Pharm J 2000; 265: 602.

Bush J, Langley C A, Wilson K A . The corporatization of community pharmacy: implications for service provision, the public health function, and pharmacy's claims to professional status in the United Kingdom. Res Social Adm Pharm 2009; 5: 305–318.

Taylor K, Harding G . Corporate pharmacy: implications for the pharmacy profession, researchers and teachers. Pharm Educ 2003; 3: 141–147.

Selfe R W . Local pharmacies will always be more accessible. Pharm J 2003; 270: 437.

Banks P J . Proud to be a supermarket pharmacist. Pharm J 2003; 270: 437.

Wilson J . Supermarket pharmacy provides time for proper discussion with patients. Pharm J 2003; 270: 783.

Sidhu A . Glorified shelf stackers? Pharm J 2003; 270: 152.

Ritzer G . The McDonalisation of Society. Available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1542-734X.1983.0601_100.x (accessed November 2015).

Agich G J, Forster H . Conflicts of interest and management in managed care. Camb Q Healthc Ethics 2000; 9: 189–204.

Dentistry. Seasonal delights. 2015. Available at https://www.ft-associates.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/PVI-Nov-2015.pdf (accessed December 2015).

Dentistry. Hot Property. 2015. Available at https://www.ft-associates.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/PVI-September-2015.pdf (accessed December 2015).

Dentistry. Bucking the trend – yet again. 2014. Available https://www.ft-associates.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Dentistry-Article-Oct-2014.pdf (accessed December 2015).

Christies & Co. Dental Focus Autumn 2015. 2015.

National Association of Specialist Dental Accountants & Lawyers. Demand and not profitability dominates dental practice values. 2015. Available at https://www.nasdal.org.uk/assets/press-releases/Goodwill%20survey%20QE%20April%2030th-June%202015.pdf (accessed July 2015).

National Association of Specialist Dental Accountants & Lawyers. Profits of the average private practice just outstrip NHS practice according to NASDAL survey. 2015. Available at http://www.nasdal.org.uk/press-releases.php (accessed July 2015).

National Association of Specialist Dental Accountants & Lawyers. NASDAL Benchmarking Statistics Private practice profits leave NHS behind. 2016. Available at http://www.nasdal.org.uk/assets/press-releases/Private%20Practice%20Profits%20leave%20NHS%20behind.pdf (accessed January 2017).

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the British Dental Association Trust Fund/Shirley Glasstone Hughes Trust Fund for funding this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

O'Selmo, E. Dental corporates abroad and the UK dental market. Br Dent J 225, 448–452 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.740

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.740

This article is cited by

-

Rationalisation and 'McDonaldisation' in dental care: private dentists' experiences working in corporate dentistry

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Developments in oral health care in the Netherlands between 1995 and 2018

BMC Oral Health (2020)