Key Points

-

Suggests ways to expedite healing.

-

Suggests ways to improve patient comfort.

-

Suggests a minimal intervention perio-restorative approach for improving anterior dental aesthetics.

Abstract

The rehabilitation of anterior dental aesthetics involves a multitude of disciplines, each with its own methodologies for achieving a predefined goal. The literature is awash with different techniques for a given predicament, based on both scientific credence, as well as empirical clinical judgements. An example is crown lengthening for correcting uneven gingival zeniths, increasing clinical crown lengths, and therefore, reducing the amount of maxillary gingival display that detracts from pleasing pink aesthetics. Many procedures have been advocated for rectifying gingival anomalies depending on prevailing clinical scenarios and aetiology. This paper presents a minimally invasive technique for crown lengthening for short clinical crowns concurrent with excessive maxillary gingival display, which is expedient, maintaining the inter-proximal papilla, mitigating morbidity, reducing post-operative inflammation, and increasing patient comfort. In addition, with a similar ethos, a minimally invasive tooth preparation approach is presented for achieving optimal white aesthetics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In an era of medical and dental minimal intervention protocols, the professions are perpetually seeking modalities that reduce trauma, morbidity, accelerate healing and reduce clinical treatment time with predictable and long-lasting results. This tendency is prevalent across all dental disciplines, where patient demands for expediency are fuelling treatments for producing 'immediate results' accompanied by minimal discomfort. Many dental therapies are promoting procedures with prefixes such as 'short', 'less', 'rapid' and 'minimal'. Many of these modalities have sound scientific platforms, but others lack long-term data. The principle of minimal intervention and instancy is laudable, but unless evidence-based and predictable, the resultant treatment is futile and often detrimental, requiring greater intervention later for correcting unwanted eventualities.

An excessive amount of maxillary gingival display, concomitant with short clinical crowns, is generally regarded as unpleasing during smiling, having a negative personal and social impact.1,2 However, relatively simple periodontal crown lengthening surgery, with or without a restorative adjunct, can yield remarkably satisfying aesthetic results for boosting patient confidence and satisfaction.3 The management of unwanted gingival display varies according to aetiology and includes crown lengthening, local muscle relaxants, orthodontics, and dentoalveolar or orthognathic surgery.4 Therefore, differential diagnosis is crucial for arriving at a precise diagnosis, and subsequent treatment planning that is realistic and feasible.

Aetiology

An excessive gingival display, or 'gummy smile', has its origins from skeletal, muscular or dentogingival abnormalities including elongated maxillae, short and/or hypertonic maxillary lips, dentoalveolar compensation, Angle's Class II (ii) or Class III occlusions, altered passive eruption (APE),5 or a combination of these causes. The most frequently encountered dentogingival phenomenon manifests as an excessive amount of gingiva covering the clinical crown of the tooth, resulting in pronounced gingival display. The most common aetiology is altered passive eruption (APE), a failure of the passive stage of tooth eruption, leaving the gingival margin in a more coronal location.6 APE is classified into two types with two further subdivisions in each type,7 depending on the position of the mucogingival junction and alveolar bone crest. In Type 1, a wide band of keratinised tissue is evident (apical location of mucogingival junction), and in subtype A, the alveolar bone crest is within the norm with adequate space for the biological width. In Type 1B, the bone crest approximates the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ), leaving little room for the connective tissue and epithelial attachments (biologic width). In Type 2, the mucogingival junction is within the norm, and in subtype A, the alveolar crest at a normal location to accommodate the biologic width, while in subtype B, the bone is close to the CEJ, with reduced space for the biologic width (Fig. 1).

Clinical decision making

If the diagnosis is confirmed as APE, then the treatment modality is crown lengthening for increasing the clinical crown length and concurrently reducing the excessive maxillary gingival display. Although the treatment of choice for APE is crown lengthening, the latter means different things to different people. For some, crown lengthening simply implies gingivectomy by an incision, electrosurgery, laser or rotary curettage for achieving the desired objective, while for others it translates to gingivectomy combined with ostectomy and osteoplasty in a pre-determined and calculated manner. However, the method of crown lengthening depends on the type of APE, and whether or not restorations are contemplated in conjunction with the proposed perioplastic surgery. If the teeth are sound, and the only reason is increasing the clinical crown length and reducing excessive gingiva display, then the clinical protocol depends on the location of the mucogingival junction, that is, linear width of the keratinised gingiva, and the relationship of the alveolar crest to the CEJ. If diagnosed as APE Type 1A, gingivectomy alone will suffice, while for Type 1B gingivectomy plus ostectomy and osteoplasty is necessary for creating space for the biologic width. Conversely, for Type 2B, gingivectomy is contraindicated as it would reduce the linear width of the keratinised gingiva, and therefore, an intra-sulcular incision is advised for accessing the alveolar crest while preserving the soft tissue architecture. For Type 2A, osseous resection is superfluous since the alveolar crest is at the normal location, but mandatory in Type 2B for creating the necessary space for the biologic width.8 If soft-tissue excision via a gingivectomy would result in a postoperative keratinised gingival width of less than 3 mm as in Type 2 cases, an apically positioned flap should be considered as an alternative to a simple gingivectomy (Table 1).

Alternately, if restorative rehabilitation is also contemplated for rectifying anterior white aesthetics, in combination with perioplastic surgery for pink aesthetics, a different approach is necessary. In situations where APE is present concomitant with tooth surface loss due to tooth wear, dental caries, or trauma, restorative treatment for aesthetic restitution is necessary for the affected tooth or teeth. In these circumstances, the starting point is the incisal edge position of the proposed restoration(s), which is determined by the degree of tooth exposure at the habitual lip position, a repose smile and laughter.9 Once the latter is finalised, and the width/length ratio of the tooth/teeth is calculated, the next step is the location of the cervical margin.10 If aesthetic objectives are achievable by confining the restorations to the incisal 1/3 or 2/3, the location of the cervical margin is, of course, irrelevant. However, if the restoration is to cover the entire facial surface of the tooth, the location of the restorative cervical margin is imperative for preventing violation of the biological width. Therefore, it is important to realise that for simultaneously correcting pink and white aesthetics, the definitive restoration and CEJ act as reference points,11 whereas for correcting only pink aesthetics, the CEJ alone serves as the anatomical reference landmark.

Case study

The relationship between periodontics and restorative/prosthetic dentistry is symbiotic. Similar to conjoined twins, one cannot survive without the other. Providing beautiful restorations without considering their impact on periodontal health is an exercise in futility, inviting failure and catastrophe. The case study below shows correcting both APE (pink aesthetics), and tooth surface loss or TSL (white aesthetics), using minimally invasive approaches for both crown lengthening, and tooth preparation, respectively. Particular attention should be paid to clinical decision making and protocols in order to achieve a synergistic relationship between the restorations that respect the integrity of the surrounding periodontium.12

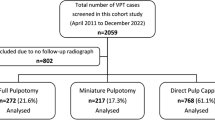

Perio-restorative analysis

A 24-year-old woman attended the Speciality Clinic at the Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University dental hospital seeking improvement of her dental aesthetic predicament. Her chief complaint was small anterior teeth with a gummy smile. An aesthetic analysis from the dento-facial perspective revealed minimum and inadequate maxillary tooth exposure at the habitual ('rest') lip position, usually 3–4 mm for women.13 During a relaxed smile, an excessive amount of gingival display was evident, especially on the right side, with a smile line not coincident with the curvature of the mandibular lip (Fig. 2). In addition, the maxillary anterior teeth were abraded due to attrition with worn and serrated edges resulting in a lack of increasing anterior-posterior incisal angle embrasures. Evaluation during an exaggerated smile, especially during speech and laughter, showed excessive gingival display and erratic gingival zeniths of the anterior maxillary sextant.

Intra-oral examination confirmed a severely worn maxillary dentition, flattening of the mandibular anterior teeth, and a coronally located maxillary frenal attachment with a maxillary median diastema measuring 1 mm. The short clinical crown lengths of the maxillary incisors and canines, combined with a wide band of keratinised gingiva (with melanin pigmentation) resulted in the excessive gingival exposure mentioned above. Also, a defective composite restoration was present on the right lateral incisor, impinging on the gingival margin (Fig. 3). Tooth surface loss (TSL) was substantial, exposing the underlying dentine strata at the incisal edges of both maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth (Fig. 4). The patient divulged stress-related bruxism and had previously been prescribed a nocturnal night-guard for mitigating her grinding habit. In addition, measurements of the maxillary anterior teeth revealed disproportionately large width/length (w/l) ratios of the incisors and canines. For example, the width of the right maxillary central was 8 mm, with a length of 6 mm, correlating to a w/l ratio of 1.3 (Fig. 5), compared to the acceptable average w/l ratio of 0.78.14 The inter-tooth relationship also required correction for achieving a pleasing anterior-posterior distal width progression from the central incisor to the canines.15

Diagnosis and treatment planning

The wide band of keratinised gingiva with short clinical crowns is consistent with APE Type 1. The latter is also the cause of excessive gingival display due to erratic passive tooth eruption patterns. In addition, the tooth wear exposing dentine is classified as scale 3, according to the Smith and Knight Tooth Wear Index (TWI).16 The attrition had also caused a loss of occlusal vertical dimension (OVD). The dual diagnosis of APE and TSL necessitated a perio-restorative approach for rectifying both pink and white aesthetics for reducing gingival display and increasing length of the teeth in the maxillary anterior sextant for correcting capricious tooth proportions. In addition, rehabilitation of white aesthetics necessitated closing the median diastema, reinstating incisal embrasure angles, and establishing a pleasing anterior-posterior distal width progression from the central incisors to the canines.

The dual modality perio-restorative treatment plan involved two distinct phases; first, perioplastic aesthetic crown lengthening for correcting pink aesthetics, followed by a restorative phase for replacing the lost tooth substrate for restitution of white aesthetics.

Following supportive prophylaxis therapy and tooth whitening, a diagnostic wax-up was fabricated with correct proportions of the maxillary anterior teeth. The wax-up was then duplicated in plaster for creating a vacuum stent for an intra-oral surgical guide for assessing the amount of tooth display during the habitual ('rest') lip position, and parallelism of the smile line in relation to the curvature of the mandibular lip during a repose smile, speech and laughter. Since treatment involved both periodontal and restorative rehabilitation, the guide served as a reference for guiding the extent of crown lengthening, in combination with increasing the clinical crown length for achieving a satisfactory incisal edge position of the maxillary teeth, accompanied by an increase of the anterior vertical overbite. This would open the bite anteriorly by 2 mm for re-establishing the OVD using the Dahl concept,17 allowing intentional over-eruption of the posterior teeth. For example, the existing length of the left maxillary central incisor is 6 mm, and proposed clinical crown length is about 10.5 mm (Fig. 6). In order to achieve an acceptable w/l requires crown lengthening of around 2.5 mm, plus increasing the incisal length by 2 mm. In addition, to close the maxillary median diastema, the width of the centrals needed to be increased by 0.5 mm, from 8 mm to 8.5 mm. With these new dimensions, the w/l ratio of the central incisors would be restored to within acceptable normal limits:

Existing w/l ratio of tooth #21: 8 mm/6 mm = 1.3

Proposed w/l ratio of tooth #21: 8.5 mm/10.5 mm = 0.8

Furthermore, incisal embrasures angles, gingival aesthetic line (GAL),18 and satisfactory distal width progression were evaluated with the diagnostic wax-up (Fig. 7), and gaining the patient's approval before commencing treatment. It is important to note that the surgical stent acts as a guide for facilitating treatment, and should not be regarded as a facsimile of the final aesthetic result, which is often modified as treatment progresses. The remaining treatment would be provided at a later date including frenectomy, replacing lost tooth substrate at the incisal edges of the anterior mandibular teeth with direct resin-based composite restorations, addressing the posterior restorations and missing teeth, and providing the patient with a new night-guard for mitigating attrition.

Rehabilitating pink aesthetics

The minimally invasive perioplastic microsurgery for aesthetic crown lengthening was performed as follows. Initially, using the intra-oral surgical guide (Fig. 8), bleeding points were placed for determining the position of the gingival zeniths of the incisors and canines. Since an adequate width of keratinised gingiva was present, external bevel gingivectomy incisions were used, located within the facial line angles of the incisors and canines for preserving the interdental papilla (Fig. 9). Since the primary objective of the perioplastic surgery was rehabilitation of pink aesthetics, crown lengthening was confined to the facial aspects of the teeth without involving the palatal surfaces. The incised superfluous tissue was subsequently removed with a curette for visualising the newly established position of the free gingival margin (FGM) (Figs 10 and 11). Using a periodontal probe, bone sounding was measured from the FGM to the mid-facial alveolar crest for determining the extent of osseous recession necessary for establishing the new biological width. Since the bone crest was almost approximated the CEJ, the diagnosis of APE Type 1B was confirmed, and therefore, 2 mm ostectomy from the CEJ was necessary. The microsurgery approach involved intra-sulcular reflection of the FGM with a Zekrya gingival retractor for gaining access to the alveolar crest, as well as protecting the gingival tissues during the ostectomy, which was performed with a diamond coated piezo-surgery tip under copious saline irrigation (Fig. 12). The completed surgical procedure created the correct GAL on both the right and left side of the maxillary sextant (Fig. 13).

The intra-oral surgical guide as a reference for determining the amount of crown lengthening, and increasing the length of the maxillary anterior teeth, for example, for tooth #11, the existing clinical crown length is 6 mm, and the proposed clinical crown length is approximately 10.5 mm. To achieve this objective requires crown lengthening of around 2.5 mm, plus 2 mm increase in incisal length

The healing was uneventful, comfortable and rapid; Figure 14 shows the outcome four days later, while Figure 15 show healing after two weeks.

Rehabilitating white aesthetics

A period of three months was allowed for stabilisation and maturation of the gingival zeniths, and also for shade rebound following tooth whitening, before proceeding with the restorative phase; the dento-facial view shows reduced maxillary gingival display and brighter teeth (Fig. 16).

Three month healing shows reduced maxillary gingival display, improved gingival zenith locations, increased clinical crown lengths, and brighter teeth following home tooth whitening (compare with Fig. 2)

The restorative phase involved replacing the missing tooth substrate due to TSL, closing the maxillary median diastema, as well as restoring pleasing w/l ratios of the incisors and canines. The canine tips were restored with resin-based composite without any preparation. The right lateral incisor was prepared for a full coverage, all-ceramic crown, while the centrals and left lateral incisor were destined for porcelain laminate veneers (PLVs). The tooth preparation for the latter was minimally invasive, limited to defining finish lines with incisal wrap, and keeping within the enamel layer without exposing dentine (Fig. 17). Also, to conceal the cement line, the tooth preparation margins of the crown on the right lateral incisor were located 0.5 mm subgingivally. and PLVs were placed 0.5 mm subgingivally. After impressions (Fig. 18), the dental laboratory fabricated an e-Max crown (IPS e-Max, Ivoclar-Vivadent, Schaan, Lichtenstein) and three feldspathic PLVs (Fig. 19), which were cemented using an adhesive technique. The post-operative result shows impeccable integration of the restorations with the adjacent teeth, as well as a harmonious relationship with the surrounding healthy periodontium (Figs 20, 21, 22, 23). The dual treatment objectives, rehabilitation of pink and white aesthetics with a perio-restorative approach, are confirmed by the dento-facial view (Fig. 24). The amount of maxillary gingival display is reduced by minimally invasive crown lengthening, while TSL is replaced with minimally invasive restorative modalities producing w/l ratios that are within normal ranges, all culminating in pleasing anterior aesthetics.

Post-operative incisal view showing replacement of the TSL (compare with Fig. 4)

Post-operative frontal view showing impeccable gingival health surrounding the crown and PLVs (compare with Fig. 3)

Post-operative dento-facial view showing restitution of both pink and white aesthetics (compare with Fig. 2)

Discussion

One of the most common uses for perioplastic surgical procedures is crown lengthening, either for restorative or aesthetic reasons. This includes gaining tooth substrate for additional retention and resistance form for restorations, or for correcting gingival aberrations in the anterior, aesthetically sensitive regions of the oral cavity. Numerous methodologies for crown lengthening are recommended in the dental literature including gingivectomy, gingivoplasty, flap elevation with osseous resection, apical flap repositioning (with or without osseous resection), flapless, multi-staged, papilla preservation, and immediate approaches.19 The choice of protocol depends on patient specific factors such as constitution, medical history, medication, bone/periodontal biotypes, width of keratinised gingiva, locations of the FGM and CEJ, anticipated surgical endpoint of perioplastic procedures with or without restorative adjuncts, and home oral hygiene practices. Furthermore, the clinical techniques employed have a significant bearing on the long-term stability of these procedures, including the degree of post-surgical FGM rebound that depends on the periodontal biotype, amount of osseous resection, conditioning of the root surface, and location of flap repositioning.20 Another issue is whether or not visualising bone during osseous resection influences the outcome of crown lengthening procedures. A recent study concludes that although the local levels of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) and osteoprotegerin (OPG) were increased for an open flap approach at three months, but the gingival margin stability was similar for both open flap and flapless approaches after 12 months.21

The ubiquitously quoted 3 mm alveolar reduction emanates from the premise that the average biologic width is 2 mm, plus a mean sulcus depth of 1 mm. However, to date, there is no unequivocal dimension for the biologic width in humans, varying on the tooth type, tooth site, periodontal disease, and post-surgical healing after procedures such as crown lengthening.22 Nevertheless, assuming periodontal health is evident, the general consensus for clinical objectives of the biological width is 2 mm.

If restorations are planned, the time for delivery of these is also a matter of contention. Some authorities believe that a period of six months to a year is allowed for stability after surgery. However, others believe that soft tissue stability is evidenced 8–12 weeks post-surgically, and although the final restorations can be contemplated at this time,23 remodelling of the supracrestal tissues of the biological width takes much longer at around six months.24 Also, the alveolar crest level (normal, low or high) should be ascertained before deciding where to place the restorative margins in relation to the FGM (supragingival, equigingival or subgingival),25 and closely monitored for post-operative recession in aesthetically sensitive areas.26 Finally, the implications of clinical changes to adjacent and non-adjacent sites compared to treated sites should be considered, especially when crown lengthening is performed solely for aesthetic reasons.27

The two-stage crown lengthening procedure involves an initial osseous resection, followed later by gingivectomy to compensate for unpredictable soft tissue healing. Another method is deliberately violating the biologic width by locating the restorative margins subgingivally, either into the epithelial, or connective tissue attachment and then waiting for the reestablishment of the biologic width. The rationale for the latter is that biologic width violation is commonplace during restorative procedures without deleterious effects, and natural healing does re-establish a new biologic width by osseous remodelling. However, if healing is not as anticipated, osseous contouring may be necessary at a later date for creating the requisite space for the biologic width.28

Due to the minimal initial trauma of a microsurgical approach shown in this case study, the primary tissue healing and subsequent maturation is expedited, and therefore, potentially reduces the time before delivery of the definitive restorations.29 In addition, since the interproximal papillae are excluded from surgery trauma, gingival embrasure recession or formation of the so-called 'black triangles' are obviated. Furthermore, a microsurgical protocol for crown lengthening has similar outcomes to open flap surgery after 12 months,30 and therefore, may be indicated for thin or intermediate bone biotypes when minimal ostectomy and osteoplasty are anticipated, whereas, with thick bone biotypes, extensive ostectomy may be required, necessitating an open flap approach. In these situations, complete bone visualisation is essential for adequate access for osseous contouring without traumatising the overlying gingival tissues.

Finally, consideration of the degree of free gingival margin (FGM) rebound is crucial for ensuring long-term stability of the gingival architecture and profile. The amount of rebound is estimated to be between 1 mm to 3 mm following a period of six months to one year healing.31 Therefore, the initial gain in clinical crown length may be reduced over a period of a year, negating the initial gain.32,33 Some studies report that the amount of FGM rebound depends on the positioning of the flap margin to the alveolar crest after osseous resection; the closer the flap is to the alveolar crest (less than 1 mm), the greater the degree of FGM rebound for creating space for a new biologic width.34 Also, the degree and incidence of FGM rebound are greater with thick compared to thin periodontal biotypes. Another factor affecting long-term stability is the amount of bone removal during ostectomy for achieving the desired 3 mm from the FGM to the alveolar crest, and it has been suggested that at least 3 mm of bone be resected if the initial gain in clinical crown length is to be maintained over time. Hence, the amount of bone removal takes precedence to the long-term stability rather than the position of the flap post-surgically.35

Conclusion

Clinical crown lengthening is indicated for gaining additional hard tissue for retention and resistance form for restorations, allowing placement of supragingival margins for maintenance of periodontal health and facilitating clinical and laboratory procedures. In addition, crown lengthening in the aesthetic zone is invaluable for correcting erratic gingival anomalies and enhancing both pink and white anterior aesthetics. Numerous surgical techniques are proposed for perio-restorative rehabilitation, with similar outcomes, but vary according to systemic and local factors. The minimally invasive surgical (perioplastic microsurgery) and restorative approaches documented in this paper decrease trauma, reduce treatment time, accelerate rehabilitation by expediting healing, increase patient comfort, and offer long-term stability and predictability with pleasing aesthetic outcomes.

References

Malkinson S, Waldrop T C, Gunsolley J C, Lanning S K, Sabatini R . The effect of esthetic crown lengthening on perceptions of a patient's attractiveness, friendliness, trustworthiness, intelligence, and self-confidence. J Periodontol 2013; 84: 1126–1133.

Kokich V O, Kiyak H A, Shapiro P A . Comparing the perception of dentists and lay people to altered dental esthetics. J Esthetic Dent 1999; 11: 311–324.

Silva C O, Soumaille J M, Marson F C, Progiante P S, Tatakis D N . Aesthetic crown lengthening: periodontal and patient-centred outcomes. J Clin Periodontol 2015; 42: 1126–1134.

del Castillo R, Hernández A M, Ercoli C . Conservative orthodontic-prosthodontic approach for excessive gingival display: A clinical report. J Prosthet Dent 2015; 114: 3–8.

Dolt III A H, Robbins J W . Altered passive eruption: An aetiology of short clinical crowns. Quintessence Int 1997; 28: 363–372.

Craddock H L, Youngson C C . Eruptive tooth movement – the current state of knowledge. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 385–391.

Coslet J G, Vanarsdall R, Weisgold A . Diagnosis and classification of delayed passive eruption of the dentogingival junction in the adult. Alpha Omegan 1977; 70: 24–28.

Allen E P . Surgical crown lengthening for function and aesthetics. Dent Clin North Am 1993; 37: 163–179.

Ahmad I . Anterior dental aesthetics: dentalofacial perspective. Br Dent J 2005; 199: 81–88.

Ahmad I . Anterior dental aesthetics: dental perspective. Br Dent J 2005; 199: 135–141.

Joly J C, Mesquita C P F, Carvalho S R . Flapless aesthetic crown lengthening: A new therapeutic approach. Revista Mexicana de Periodontología 2011; 2: 103–108.

Nautiyal A, Gujjari S, Kumar V . Aesthetic Crown Lengthening Using Chu Aesthetic Gauges And Evaluation of Biologic Width Healing. J Clin Diagn Res 2016; 10: ZC51–ZC55.

Trushkowsky R, Arias D M, David S . Digital smile design concept delineates the final potential result of crown lengthening and porcelain veneers to correct a gummy smile. Int J Esthet Dent 2016; 11: 338–354.

Ker A J, Chan R, Fields H W, Beck M, Rosenstiel S . Esthetics and smile characteristics from the layperson's perspective. JADA 2008; 139: 1318–1327.

Gillen R J, Schwartz R S, Hilton T J, Evans D B . An analysis of selected normative tooth proportions. Int J Prosthodont 1994; 7: 410–417.

Smith B G, Knight J K . A index for measuring the wear of teeth. Br Dent J 1984; 156: 435–438.

Dahl B L, Krogstad O . The effect of a partial bite raising splint on the occlusal face height. An x-ray cephalometric study in human adults. Acta Odontol Scand 1982; 40: 17–24.

Ahmad I . Anterior dental aesthetics: gingival perspective. Br Dent J 2005; 199: 195–120.

Lee EA . Aesthetic crown lengthening classification, biological rationale, and treatment planning considerations. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent 2004; 16: 769–778.

Ribeiro, Hirata, Reis et al. Open-flap versus flapless esthetic crown lengthening: 12-month clinical outcomes of a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol 2014; 85: 536–544.

Ribeiro F V, Hirata D Y, Reis A F et al. Open-flap versus flapless esthetic crown lengthening: 12-month clinical outcomes of a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol 2014; 85: 536–544.

Schmitd J C, Sahrmann P, Weiger R, Schmidlin P R, Walter C . Biological width dimensions – a systematic review. J Clin Periodontal 2013; 40: 493–504.

Fletcher P . Biologic rationale of aesthetic crown lengthening using innovative proportion gauges. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2011; 31: 523–532.

Herrero F, Scott J B, Maropis P, Yukna R A . Clinical comparison of desired versus actual amount of surgical crown lengthening. J Periodontal 1995; 66: 568–571.

Kois J C . The restorative-periodontal interface: Biological parameters. Periodontol 2000 1996; 11: 29–38.

Brägger U, Lauchenauer D, Lang N P . Surgical lengthening of the clinical crown. J Clin Periodontol 1992; 19: 58–63.

Nobre C M G, de Barros Pascoal A.L, Albuquerque Souza E et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of crown lengthening on adjacent and non-adjacent sites. Clin Oral Invest 2016; 21: 7–16

Fletcher P . Biologic Rationale of Esthetic Crown Lengthening Using Innovative Proportion Gauges. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2011; 31: 523–532.

Paolantoni G, Marenzi G, Mignogna J, Wang H-L, Blasi A, Sammartino G . Compassion of three different crown-lengthening procedures in the maxillary anterior esthetic regions. Quintessence Int 2016; 47: 407–416.

Ribeiro F V, Hirata D Y, Reis A F et al. Open-flap versus flapless esthetic crown lengthening: 12-month clinical outcomes of a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol 2014; 85: 536–544.

Sonick M . Esthetic crown lengthening for maxillary anterior teeth. Compend Contin Educ Dent 1977; 18: 807–812.

Pontoriero R, Carnevale G . Surgical crown lengthening: A 12-month clinical wound healing study. J Periodontal 2001; 72: 841–848.

Haempton T J, Dominici J T . Contemporary crown-lengthening therapy: a review. J Am Dent Assoc 2010; 141: 647–655.

Deas D E, Moritz A J, McDonnell H T, Powell C A, Mealey B L . Osseous surgery for crown lengthening: A 6-month clinical study. J Periodontal 2004; 75: 1288–1294.

Lanning S K, Waldrop T C, Gunsolley J C, Maynard J G . Surgical crown lengthening: Evaluation of the biologic width. J Periodontal 2003; 74: 468–474.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to Mr Amed Kharfan, Zercon Smile Dental Laboratory, Riyadh, KSA for the ceramic work presented in the case study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Harbi, F., Ahmad, I. A guide to minimally invasive crown lengthening and tooth preparation for rehabilitating pink and white aesthetics. Br Dent J 224, 228–234 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.121

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.121

This article is cited by

-

Treatment of excessive gingival display using conventional esthetic crown lengthening versus computer guided esthetic crown lengthening: (a randomized clinical trial)

BMC Oral Health (2024)

-

Smile makeover treatments

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

Minimal invasive microscopic tooth preparation in esthetic restoration: a specialist consensus

International Journal of Oral Science (2019)

-

Should we fear direct oral anticoagulants more than vitamin K antagonists in simple single tooth extraction? A prospective comparative study

Clinical Oral Investigations (2019)