Key Points

-

Suggests that the evidence with regard to an association between oral health and dementia is weak because of the lack of well-designed cohort and case-control studies and variation in how dementia and oral health are defined and measured.

-

Highlights that dementia and cognitive decline are risk factors for poor oral health.

-

Suggests that patients with suboptimal oral health appear to have an associated increased risk of cognitive impairment, but more evidence from different settings is required.

Abstract

This is the fourth and final paper of a series of reviews undertaken to explore the relationships between oral health and general medical conditions, in order to support teams within Public Health England, health practitioners and policy makers. This review aimed to explore the most contemporary evidence on whether poor oral health and dementia occurs in the same individuals or populations, to outline the nature of the relationship between these two health outcomes and to discuss the implication of any findings for health services and future research. The review was undertaken by a working group comprising consultant clinicians from medicine and dentistry, trainees, public health and academic staff. Whilst other rapid reviews in the current series limited their search to systematic reviews, this review focused on primary research involving cohort and case-control studies because of the lack of high level evidence in this new and important field. The results suggest that poor oral hygiene is associated with dementia, and more so amongst people in advanced stages of the disease. Suboptimal oral health (gingivitis, dental caries, tooth loss, edentulousness) appears to be associated with increased risk of developing cognitive impairment and dementia. The findings are discussed in relation to patient care and future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Increasing dementia incidence and prevalence in England has led to a commitment to provide the best support for people with dementia and other neurodegenerative diseases, and further research.1 This is timely as dementia, together with cognitive decline, presents significant challenges for patients, and their carers, practitioners and health systems.1

Dementia (F00-F03) is described in the International Classification of Disease version 10 (ICD-10) as:

'a syndrome due to disease of the brain, usually of a chronic or progressive nature, in which there is disturbance of multiple higher cortical functions, including memory, thinking, orientation, comprehension, calculation, learning capacity, language, and judgement. Consciousness is not clouded. The impairments of cognitive function are commonly accompanied, and occasionally preceded, by deterioration in emotional control, social behaviour, or motivation. This syndrome occurs in Alzheimer's disease, in cerebrovascular disease, and in other conditions primarily or secondarily affecting the brain.'2

In this paper, we shall use the umbrella term 'dementia' to include cognitive impairment, as the majority of the literature used cognitive impairment scores as a diagnostic tool for dementia. It is important to note that dementia is not a specific disease, rather it is a set of symptoms that are the manifestations of different pathology. In this review we shall use the term dementia, though we acknowledge there is more than one type of dementia.2,3,4

The common causes of dementia are Alzheimer's disease (AD) and vascular dementia.3,4 AD is a physical disease where proteins build up to form structures called 'plaques' and 'tangles' in the brain. This leads to the loss of connections between nerve cells, and eventually to the death of nerve cells and loss of brain tissue. There is also a shortage of some important chemicals in the brain. Memory difficulties are usually the earliest symptoms of AD, other symptoms will involve problems with aspects of thinking, reasoning, perception or communication.3 There is currently no cure for dementia, although a number of risk factors have been identified, and modification of these may impact on the presentation and progression of the condition.

The risk factors for dementia are multifactorial and apply throughout the life course. At a population level, educational attainment in early life, such as the number of years spent in education, was found to be protective against dementia.5 A higher level of education appears to delay the onset of dementia by several years.5 Factors such as hypertension, type II diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, cognitive activity, social activity, exercise, alcohol use, diet and smoking are also proposed to play a role in the development of dementia.3,5

Oral diseases and cancers affect 3.9 billion people globally, and untreated caries in the permanent dentition is the most prevalent health condition in the world.6 In the UK, the latest national survey suggests that 31% of dentate adults had obvious caries and 6% were edentulous; almost half of dentate adults (45%) had periodontal pocketing ≥4 mm, although for those affected (37%) the disease level was moderate; the prevalence of pocketing <6 mm increased with age.7 Caries and periodontal disease are thus more common than other chronic health conditions and increase in older age.

Good oral health is an important aspect of general health and wellbeing contributing to self-esteem, dignity, social integration and nutrition. Oral diseases share common risk factors with other non-communicable diseases,8 and affect quality of life.7 For example, poor oral health in older people has been shown to be associated with pain and discomfort,9 and reduced appetite.10 Those people with moderate and advanced levels of dementia have greater functional dependency, and are often reliant on others for their daily oral care. Some individuals present with behaviour and communication difficulties, and may resist assistance (for example, not opening mouth, refusing oral care). Furthermore, people with dementia may lose the capacity to clean their teeth regularly resulting in more dental plaque accumulation, thus, increasing their risk of developing periodontal disease and dental caries.

Biological plausibility for the association between poor oral health and development of dementia is suggested by an increase in systemic inflammatory markers in the presence of both conditions. For example, periodontitis has been shown to increase the level of those inflammatory markers which are also implicated in the development of dementia.11,12 There is emerging evidence from studies that people with dementia have poor oral health but the relationship between the two diseases is not clear. This review aims to synthesise the contemporary evidence exploring the relationship between oral health and dementia.

Methods

A rapid review of articles reporting primary research published between 2005 and October 2015 was undertaken to investigate the relationship between dementia and oral health in line with Khangura et al. methodology.13 While other reviews in this series limited their scope to systematic reviews, this present review was expanded to focus on primary research, because of the lack of high level evidence in this evolving field. The findings present a review of primary evidence from cohort and case-control studies with separate data tables for each oral health outcome. Given the paucity of primary research and to ensure completeness, the cross-sectional studies were also sourced as background but did not contribute to the results. During data synthesis, two systematic reviews exploring the relationship between cognitive decline and oral health were published and are included with this review to provide a contemporary body of evidence.

Search syntax was developed based on subject knowledge, MeSH terms and task group agreements (Box 1). This was followed by systematic title and abstract searches conducted by two independent researchers (JS and YR) on four electronic databases: Cochrane, Embase, MEDLINE (R), and PsycINFO. The search identified 1,431 potentially relevant abstracts which were screened in duplicate for relevance. This was followed by an assessment of 91 full text articles using explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria planned a priori. The inclusion criteria for papers were as follows: a defined diagnosis of dementia or cognitive impairment using a validated measure, a defined oral health outcome using a validated measure, and for the study to be a systematic review, randomised controlled trial, cohort or case-controlled study. Papers were excluded if dementia was not the primary focus or they contained only a proposed research protocol or were published before September 2005. The following information was extracted from each paper: author, year, title, journal, population studied, oral disease/intervention, definitions used, methods, comparison/intervention and controls, outcomes, results, authors' conclusions, quality and quality justification as shown in the data extraction Tables S1,S2 (supplementary information available online).

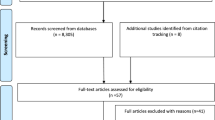

In total, 16 papers were included in the final synthesis: 11 cohort and five case-control studies. They ranged from a sample size of 59 up to 11,140 participants, with data drawn from 28 countries. Most studies were small and there was considerable variation in how oral health outcomes were assessed, and the presence of a diagnosis of dementia or cognitive impairment was generally not reliably determined. A flow diagram of the process is shown in Figure 1.

Critical appraisal was undertaken using the features of the Newcastle-Ottawa tool for cohort and case-control studies.14 Studies were rated out of 10, with those scoring three and under considered low and those scoring seven and above rated as high quality (Supplementary Online Tables 1,2).

The evidence presented here is based on a synthesis of disparate primary studies (N = 16) of varying quality: high (N = 5), medium (N = 8) and low (N = 3). Common bias included the lack of measure of exposure or outcome at baseline, failure to account for possible confounders, unclear definition of periodontal disease and lack of criteria for diagnosis of dementia. Additionally, proxy measures of oral health were used such as dental attendance and self-reported oral health.

Results: evidence synthesis

The results are reported in two main sections following the questions examined by the review group. First, whether the presence of dementia (to include cognitive decline) had an association with the oral health status of people living with the condition in a range of settings (community, care home, hospital settings). Second, whether poor oral health was a risk factor for the development of dementia (to include cognitive decline).

Part 1: Is dementia a risk factor for poor oral health?

This section of the results addresses the question of whether patients with dementia were at a higher risk of poor oral health. It is reported in six parts, each highlighting the association of dementia with different aspect(s) of oral health.

I: Dental plaque, gingival bleeding and gingivitis

Five case-control studies reporting on people with dementia were reviewed (Table S1A supplementary information available online).9,15,16,17,18 The effectiveness of oral hygiene was assessed using measures of dental plaque accumulation (on tooth and denture surfaces), gingival bleeding and gingivitis. There was variation across the studies in relation to the recording of plaque scores and gingival bleeding, with the latter measured through self-report or clinical assessment.

Older people with dementia, assessed in care homes had higher plaque scores recorded on all tooth surfaces compared with controls.18 Community dwelling people with dementia attending hospital neurology departments had higher average plaque scores compared to controls (P <0.001).16 In one small high quality prospective case-control study, an increase in MMSE score (a measure of cognitive decline) in patients with AD was correlated with an increase in dental plaque accumulation (P = 0.015);17 in this study plaque accumulation was recorded on tooth and denture surfaces using a composite score.

In another case-control study Chu et al., found that twice daily toothbrushing was less commonly practised by people with mild-level late-onset AD compared with matched controls (67% cf. 83%; P = 0.045), and this group was six times more likely to have needed support with their toothbrushing (P <0.001).15

In relation to gingivitis there was contrasting evidence; two case-control studies of community dwellers suggested that people with dementia had higher bleeding scores (P <0.001),9,10 while one small Chinese study did not report a difference.15

In summary, the studies in this section suggested that people with dementia in community and institutional settings had higher levels of plaque present and worse oral hygiene compared with controls. Regular oral hygiene was less commonly practised in people with dementia and they were more likely to require support to clean their teeth or dentures. In relation to gingivitis, there was conflicting evidence with the higher quality studies suggesting that people with dementia were more likely to have gingivitis compared with controls.

II: Periodontal disease

Three case-control studies were included (Table S1B – supplementary information available online). The presence of periodontal disease was recorded using the following measures: Community Periodontal Index (CPI), attachment loss (AL), clinical attachment loss (CAL), and probing pocket depth (PD).

These three studies investigated community dwelling people.9,15,16 In a high quality study Gil-Montoya et al.,16 suggested that periodontitis (AL >3 mm; 67% of sites) appeared to be associated with cognitive impairment after controlling for confounders such as age, sex, and education level. The proportion of sites with AL >3 mm was greater in patients with cognitive impairment compared to those with no impairment (P = 0.002). When adjusted for age, sex, education, teeth present, oral hygiene habits, and hyperlipidaemia, the odds ratio of moderately extensive AL in adults with moderate cognitive impairment was 2.64 (1.18–5.92) and severe impairment was 2.31 (1.15–4.66) (P = 0.04). In a study of patients with mild AD, de Souza Rolim et al.,9 using the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) definition of periodontal disease, reported that gingivitis and severe periodontal disease were more frequent in patients with mild AD compared with healthy controls (P = 0.002). Chu et al.,15 in a study involving older adults with mild level late-onset AD, found no evidence of an increased prevalence of advanced periodontal disease (assessed as CPITN >3 mm) between patients with dementia and matched controls.

In summary, while there are few studies examining whether people with dementia experience greater levels of periodontal disease, one high quality study suggests that the proportion of sites affected is significantly greater in patients with cognitive impairment compared with those without evidence of impairment.

III: Caries levels and saliva flow

Five papers, comprising two cohort and three case-control studies, were included (Table S1C supplementary information available online).15,17,18,19,20 Dental caries experience was defined as mean numbers of decayed, missing and filled teeth (DMFT), or surfaces (DMFS) or caries increment over a defined period. Decayed coronal and root surfaces were presented, separately if appropriate.

Chen et al.,20 in a high quality cohort study showed that adults with a diagnosis of dementia attending a dental clinic had significantly higher levels of dental caries compared to controls. Ellefson et al.,19 in a medium quality cohort study showed that older people attending a memory clinic (other than patients with AD) were at elevated risk of developing high levels of coronal and root surface caries during their first year after referral. Additionally, those who received a dementia diagnosis, other than AD, appeared to be at a particularly high risk of developing multiple carious lesions in the first year after diagnosis.19

Evidence from three case–control studies in community dwelling individuals showed no statistically significant difference in decay experience between people with dementia compared to those without.15,17,18 One study, however, did show a correlation between a decline in MMSE and increase in DMFT scores (P = 0.022).17 Chu et al., showed that people with dementia had lower unstimulated saliva flow rates (ml/min) compared with a control group (0.30 v 0.41) (P = 0.043) with reduced salivary flow being a risk factor for dental caries;15 however, there is no evidence presented of controlling for other causes of dry mouth.

In summary, there are very few studies exploring caries experience and those that exist are of variable quality (one high, three medium and one low). While there is evidence that people with dementia are at increased risk of presenting to dental services with caries and may be at higher risk of developing caries once dementia is established, the results overall are conflicting.

IV: Tooth loss

Five studies9,15,17,18,21 examine the link between dementia and tooth loss, one cohort, and four case-control as presented in Table S1D (supplementary information available online).

In a high quality cohort study Chen et al.,21 found that among affected community dwellers dementia was not associated with tooth loss, although all participants (with and without dementia), with more teeth (N >25) at first assessment, were at higher risk of tooth loss during follow-up (P <0.001). A medium quality study in Hong Kong found no significant difference in the number of missing teeth for people with AD and matched controls;15 similarly patients with AD and matched controls had similar rates of edentulism in a small low quality case-control study in Brazil.9 Adam and Preston,18 found that 70% (N = 38) of those with mild or no dementia and 63% (N = 51) of those with moderate or severe dementia were edentulous. One small medium quality case-control study in Turkey found a positive correlation between teeth present with MMSE scores in patients with AD.17

In summary, one high quality cohort study and one medium quality case-control study found no association between dementia and tooth loss, while two low quality case-controls found similar rates of edentulism between people over 59 years old with and without dementia. Just one small medium quality case-control study found a positive correlation between the stage of dementia, as determined using MMSE, and the number of teeth present; that is, in later stages of dementia patients had fewer remaining teeth.

V: Denture-related conditions

Three case-control studies of variable quality (two low and one medium) examined denture-related conditions (Table S1E – supplementary information available online).9,17,18 The findings are equivocal but highlight a range of issues relating to wearing and caring for dentures. In edentulous individuals, Adam and Preston (2006) conducted a study of care homes and showed that 60% of those with moderate to severe dementia wore no dentures at all compared with only 10% of those with no or mild dementia (P = 0.04).18 While one small case-control suggested no difference in denture wearing between those with and without mild dementia,9 other evidence from one case-control study by Hatipoglu et al., suggests that community living people with moderate or severe dementia were less likely to remove their dentures at night and were more likely to have denture-related stomatitis in both the maxilla and mandible (P = 0.001 for all).17

In summary, there is low quality evidence that people tend to stop wearing their dentures as cognitive decline increases, while the presence of denture stomatitis increases for those who continue to wear dentures.

Part 2: Is poor oral health a risk factor for developing dementia (including cognitive decline)?

This section of the results addresses the question of whether patients or communities with poor oral health were at a higher risk of developing dementia (to include cognitive decline). It is reported in five parts, each highlighting the association of dementia with the relevant aspect(s) of oral health.

I: Dental plaque, gingival bleeding and gingivitis

Six studies10,16,17,22,23,24 of variable quality were reviewed (Table S2A – supplementary information available online); four cohort and two case-control studies.

One high quality five-year prospective multi-centre cohort study found a higher than two-fold cognitive decline (modified MMSE score) in people with gingival inflammation denoted by higher gingival index scores (OR 2.54; CI 1.75–3.70), after correcting for potential confounders.22 In a medium quality large community-based cohort study in the US, Paganini-Hill found that not performing daily toothbrushing among residents of a large retirement community was associated with an increased risk of developing dementia over an 18-year period compared with those brushing three times a day (males 22%; females 65%), although this was only statistically significant in women.10

A medium quality case-control study of patients with AD reported evidence of a correlation between oral hygiene status and mini-mental state examination (MMSE) scores, but affected individuals were not significantly worse than controls.17 A four year prospective cohort study in Japan of low quality, suggested an association between not taking care of dental health and risk of dementia was partly explained by co-factors such as socio-demographics, health behaviours and forgetfulness as an early symptom of mild cognitive impairment.24 In a high quality case-control study Gil-Montaya et al. reported the odds of cognitive impairment were 15.7-fold greater in patients with a higher plaque accumulation measured by a plaque score (2.51–3 cf. 0–1); P <0.001; however, the direction of the relationship remained uncertain.16

In summary, there is evidence from cohort and case-control studies of variable quality that failure to perform toothbrushing and the presence of gingival inflammation may be risk predictors associated with developing dementia.

II: Periodontal disease

Six studies in total, five cohort and one case-control study examined periodontal disease (Table S2B – supplementary information available online).16,22,24,25,26,27

Kaye et al.,26 in a 32-year longitudinal cohort study showed that risk of cognitive decline over a decade increased by 2–5% for each tooth that had progression of alveolar bone loss or probing pocket depth.26 Furthermore, the tendency to have a lower MMSE score (denoting increased cognitive impairment) was consistently higher in older men compared with younger men and thus rates of tooth loss and periodontal disease progression during adulthood independently predicted performance on the MMSE cognitive test.26 Gil-Montoya et al.,16 reporting a case-control study, suggested that periodontitis appeared to be associated with cognitive impairment after controlling for age, sex, education level and oral hygiene habits. Risk of cognitive impairment was more than three times higher in patients with severe periodontitis compared to those with mild or no periodontitis; P <0.001.

In contrast to the above, three medium to high quality cohort studies did not show a relationship between cognitive decline and periodontal disease. Stewart et al.,22 in their 5-year cohort analysis examined periodontal health by calculating the probing depth and loss of attachment for 954 participants; their findings showed no prediction of cognitive decline and suggested that associations were substantially confounded by education and race. Arrive,27 in a 15-year cohort study showed that periodontal status was not associated with the risk of dementia before, and after, correcting for confounders. Finally, Okamoto et al.,25 in a large Japanese cohort study found no evidence of an association between the community periodontal index (CPI) and cognitive impairment.

In summary, the results are equivocal: three cohort studies (one high and two of medium quality) found no association between measures of periodontal disease and cognitive decline, while one very long cohort study of medium quality and two case-control studies of medium/high quality suggest an association.

III: Caries

Only one study of medium quality was reviewed (Table 2C – supplementary information available online). Kaye et al.,26 in a 32-year long cohort study of male veterans showed that development of new caries or need for new restorations was associated with greater risk of poor performance in MMSE and was greater in men aged over 45.5 years of age at baseline.

IV: Tooth loss

Ten studies examine the link between tooth loss (total and number of remaining teeth) and dementia, nine cohort studies (two high, five medium and two low quality)10,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 and one high quality case-control study,16 were included (Table S2D – supplementary information available online).

A 37-year medium quality cohort study found that dementia was twice as common in those with fewer than nine teeth in comparison to those with 25 or more teeth.28 A 32-year cohort study, of medium quality, found that with each tooth lost per decade, the risk of having a low cognitive test score increased by 9% to 12%.26 A five-year cohort study, also of medium quality, found those participants with one to eight remaining teeth and progressing to total tooth loss were associated with having mild memory impairment (P = 0.008); however, lower tooth count was not associated with dementia.25

Two cohort studies (one low and one medium quality) considered masticatory function by using the number of teeth remaining and denture wear. Yamamoto,24 found that those people with fewer teeth and no replacement dentures had a 1.85-fold increased risk for dementia. Paganini-Hill et al.,10 found that participants with fewer than ten upper teeth, fewer than six lower teeth, and not wearing dentures, had a higher risk of dementia compared to those with adequate natural masticatory function; the risk was significant in men (Hazard ratio [HR] = 1.91) but not in women (HR = 1.22).10

In a high quality cohort study, edentulous participants from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) were found to recall fewer words than dentate participants, however, the association was attenuated when corrected for socioeconomic status.29 One low quality cohort study also suggests a trend in the development of dementia or cognitive decline for those participants who were edentulous.23 Conversely, one medium quality cohort study found the risk of dementia was significantly lower in people with eleven or more missing teeth and a lower educational attainment (HR = 0.30; 95% CI 0.11–0.79), compared with higher educational attainment (HR = 1.07; 95% CI 0.57–2.02). Two high quality studies (one cohort and one case-control) found that neither number of teeth present nor numbers of occluding pairs of teeth were associated with cognitive decline when other risk factors were considered.16,22

In summary, while there are a number of studies relating to this aspect of oral health, there are conflicting results as evidenced by the fact that several studies of medium/high quality suggest that progressive tooth loss was associated with increasing risk of cognitive decline, while others do not. Studies researching edentulous participants have not been able to provide conclusive evidence to support an association with an increased risk of cognitive decline, however, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that this is an important area for further research.

V: Dentures

Studies involving investigation of dentures are limited to two cohort studies of low,24 and medium quality (Table S2E – supplementary information available online).10

An 18-year cohort study in a retirement community in the US suggest that for denture wearers, adequate masticatory function involving ten or more upper, and six or more lower teeth, was associated with a lower risk of dementia.10 Furthermore, the study also suggests that cleaning dentures was not significantly related to dementia.10 In contrast, a four-year cohort study in Japan showed that people with fewer teeth and no dentures were found to be at greater risk for dementia.24 Compared with people having 20 or more teeth, those with fewer teeth and no dentures were at almost twice the risk of dementia (1.85 [CI 1.04–3.31]; P = 0.04), however, general health status, health behaviour and forgetfulness attenuated the association.10,24

Thus, in summary, while the findings, of medium to low quality, regarding dentures and dementia are equivocal, there is a suggestion that masticatory function may possibly be important and further research is required.

Discussion

This rapid review highlights the paucity of evidence on the relationship between dementia and oral health over the ten-year review period. The evidence available is of mixed quality and covers a wide range of oral diseases and conditions. Given the extent of heterogeneity, meta-analysis by outcome has not been possible.

This review has a number of strengths and limitations which should be acknowledged. First, the review process conducted by a multidisciplinary team containing medical, dental, and public health professionals was considered a strength. Second, this is a 'rapid review', and so was intended to summarise existing evidence, rather than undertake quantitative synthesis. The restriction to the ten year review period, however, meant that some important earlier landmark papers may have been omitted in the searches. Third, given the nature of oral disease in this population, there is a wide range of oral conditions to be examined. Fourth, there was large heterogeneity in the studies reviewed; nonetheless, there is important learning to inform research in this field.

Certain general limitations relating to research in this field need to be acknowledged before discussing the questions posed in this review. First, there are thought to be different pathological mechanisms for the various different dementias so the potential relationships between oral health/diseases and dementias could be different for different pathologies. This makes trying to identify relationships complicated, particularly when many of the dementia diagnoses are made post mortem. Second, studies in subjects with dementia that rely on self-reported activity such as toothbrushing are subject to considerable risk of error due to reduced, and often variable, cognitive performance in this population.

Is dementia a risk factor for poor oral health?

The evidence suggests that people with dementia in community and institutional settings may have higher plaque accumulation, more teeth and surfaces affected by dental caries and more extensive periodontal disease compared to controls. A large proportion of this association may be explained by increasing age and fragility, greater functional dependence and the presence of other confounding co-morbidities. This is not, however, the finding across all the studies we explored and there is some additional learning and research warranted in communities where people's oral health appears to be less affected by dementia. The differences may well be related to the quality and conduct of the studies and further confounded by access to health and social care; nevertheless, more research using large well-designed longitudinal prospective cohort studies is required.

Is poor oral health a risk factor for dementia?

There is some limited evidence of the impact of oral health (oral hygiene, caries and number of teeth) on dementia (cognitive impairment, dementia onset and progression), including plaque accumulation, gingivitis and notably tooth loss. Risk factors and risk predictors for dementia are of interest in current research, particularly the early detection and identification of disease. Research into tooth loss and its putative role as either a predictor or as a co-factor in cognitive decline may become increasingly relevant as we move towards earlier recognition and diagnosis of dementia. There is very weak and limited evidence that in the absence of regular toothbrushing, the presence of gingivitis and reduced masticatory function may be risk factors for dementia, but there is no evidence of a direct effect on caries and periodontal disease. It is important to acknowledge that changes in MMSE could be predicted by a change in oral health status such as a loss of teeth, or vice versa. Alternatively, both may be a feature of ageing with no plausible biological link between the two phenomena.

We considered it helpful to examine further evidence from two recently published systematic reviews of cohort studies shown in Table S3 (supplementary information available online). Cerrutti-Kapplin et al.,30 reviewed ten studies, five of which are considered in our review.10,23,24,26,27 While the authors report that the relationship between periodontal disease and cognitive impairment showed conflicting results, individuals with tooth loss and suboptimal dentitions (<20 teeth) were considered at a 20% higher risk of developing cognitive decline (HR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.14 to 1.40) and dementia (HR = 1.22, 95% CI = 1.04 to 1.43) compared to those with an optimal dentition (≥20 teeth) lending some support to the hypothesis that tooth loss is associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment. Wu et al.,31 considered the number of teeth, dental caries, periodontal disease, dentures and highlighted conflicting and inconsistent findings in relation to oral health and cognitive status. The authors attributed the conflicting results to methodological weaknesses concluding that there was uncertainty about an association between oral health status and cognitive decline.31

In relation to the questions examined overall, and given the range of conditions investigated, the findings from our rapid review can only suggest the presence of potential associations with oral hygiene, gingivitis, periodontal disease, dental caries, saliva flow, tooth loss, and denture-related conditions including masticatory function. In common with Cerruti-Kaplin et al. and Wu et al., our review was unable to draw firm conclusions relating to cause and effect due to the limitations of the underpinning primary research which included: small sample size; unclear inclusion and exclusion criteria; and appropriateness of experimental design. There is, however, sufficient emerging evidence to suggest that this is an important area for further research given demographic changes and the fact that older adults have already experienced significant oral disease and its sequelae. Given the problems with existing evidence, future research should include the use of standardised criteria for planning, undertaking fieldwork and assessing outcomes as shown in Box 2.

On a practical level, daily self-care and/or assisted care is vitally important for oral health,32 whether or not people have experienced cognitive decline or dementia. It has particular relevance for those with dementia as they are often reliant on others for support to maintain oral hygiene and for the content of their diet. Therefore, for those carers and healthcare workers (HCWs) who provide direct personal care, mandatory training should be provided in oral health and hygiene, to ensure carers and HCWs have a basic competence in assessing the mouth for oral hygiene status and abnormalities. HCWs and social care professionals are often unfamiliar with pain assessment in cognitively impaired patients, therefore, training is needed to help identification and management of dental pain, which is often inaccurately attributed to other causes. Additionally, training should include practical oral hygiene measures, including techniques for those patients who may resist support for oral hygiene and denture care. This training may be more easily implemented in long term care facilities; however, the evidence suggests that people living with dementia in the community are just as likely as those in long-term care facilities to have poor oral hygiene. It is clear that every effort must be made to ensure that those living in the community should also receive the necessary oral healthcare support to secure optimal oral health.

While it has not been possible to establish that poor oral health predicts dementia, there is more concrete evidence that oral health declines in the presence of increasing cognitive impairment and dementia. Dental care must therefore be included in the wider care plan for people with dementia, in order to improve oral health throughout each individual's life course, and minimise impact on the quality of life. There must be consideration of the progressive nature of cognitive decline and dementia, and also the challenges of dental care in later stages of the disease when formulating individual oral care plans. Implementation of delivering better oral health guidelines and tailored support at various stages of dementia are also important.32

Looking to the future, there is a clear need for primary research into links between oral health and dementia, such as the link between periodontal disease and systemic inflammatory loading,23,27 along with research into whether increased inflammatory loading has an impact on the progression or development of dementia.

It is important to explore the possibility of multidisciplinary research, using standardised globally acceptable assessments and definitions.3,4,33 For example there is potential for collaboration with physiotherapists and occupational therapists to focus on the activities of daily living concurrently such as manual dexterity, gait and toothbrushing. Dieticians with their expertise in nutrition, should ensure diet plans consider oral health, and speech and language therapists should contribute with their assessment of concomitant swallowing difficulties, as these are prevalent in people with dementia and may affect oral hygiene practices and conversely, oral microflora which could have implications for pulmonary health. A multi-disciplinary approach is thus important in exploring the holistic relationships of dementia, oral health, and general health.

Conclusion

This rapid review of evidence suggests that people with dementia may experience worse oral health, with poor oral hygiene and dementia (cognitive decline/impairment) showing the most consistent association. There is conflicting evidence relating to tooth loss and the risk of cognitive decline and dementia, though professional management and satisfactory treatment of oral conditions remains important in this patient group. Overall, given the quality and paucity of research in this field, the findings should be treated with caution and require more rigorous testing in well-designed and conducted studies, preferably longitudinal in design.

References

Department of Health. Prime Minister's challenge on dementia 2020. 2015. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/414344/pm-dementia2020.pdf (accessed October 2017).

World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases – 10. Geneva: WHO, 2016.

Alzheimer's Society. Alzheimer's Society. What is Alzheimers Disease? 2015. Available at https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?downloadID=1093 (accessed October 2017).

Prince M, Knapp M, Guerchet M et al. Dementia UK: Update 2014. 2015. Available at https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2014.pdf (accessed November 2017).

Hughes T F, Ganguli M . Modifiable midlife risk factors for late-life cognitive impairment and dementia. Curr Psychiatry Rev 2009; 5: 73–92.

Marcenes W, Kassebaum N, Bernabé E et al. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990–2010 A systematic analysis. J Dent Res 2013; 92: 592–597.

Steele J, O'Sullivan I . Adult Dental Health Survey 2009. 2011. Available at https://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB01086 (accessed November 2017)

Sheiham A, Watt R . The common risk factor approach: a rational basis for promoting oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2000; 28: 399–406.

de Souza Rolim T, Fabri G M, Nitrini R et al. Oral infections and orofacial pain in Alzheimer's disease: a case-control study. J Alzheimers Dis 2014; 38: 823–829.

Paganini-Hill A, White S C, Atchison K A . Dentition, dental health habits, and dementia: the Leisure World Cohort Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60: 1556–1563.

Noble J M, Scarmeas N, Celenti R S et al. Serum IgG antibody levels to periodontal microbiota are associated with incident Alzheimer disease. PLoS One 2014; 9: e114959.

Sparks Stein P, Steffen M J, Smith C et al. Serum antibodies to periodontal pathogens are a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2012; 8: 196–203.

Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, Grimshaw J, Moher D . Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev 2012; 1: 10.

Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2000. Available at http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed October 2017).

Chu C H, Ng A, Chau A M, Lo E C . Oral health status of elderly chinese with dementia in Hong Kong. Oral Health Prev Dent 2015; 13: 51–57.

Gil-Montoya J A, Sanchez-Lara I, Carnero-Pardo C et al. Is periodontitis a risk factor for cognitive impairment and dementia? A case-control study. J Periodontol 2015; 86: 244–253.

Hatipoglu M G, Kabay S C, Güven G . The clinical evaluation of the oral status in Alzheimer-type dementia patients. Gerodontology 2011; 28: 302–306.

Adam H, Preston A J . The oral health of individuals with dementia in nursing homes. Gerodontology 2006; 23: 99–105.

Ellefsen B, Holm-Paedersen P, Morse D E, Schroll M, Andersen B B, Waldemar G . Assessing caries increments in elderly patients with and without dementia: a one-year follow-up study. J Am Dent Assoc 2009; 140: 1392–1400.

Chen X, Clark J J J, Naorungroj S . Oral health in older adults with dementia living in different environments: a propensity analysis. Spec Care Dentist 2013; 33: 239–247.

Chen X, Shuman S K, Hodges J S, Gatewood L C, Xu J . Patterns of tooth loss in older adults with and without dementia: a retrospective study based on a Minnesota cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58: 2300–2307.

Stewart R, Weyant R J, Garcia M E et al. Adverse oral health and cognitive decline: the health, aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013; 61: 177–184.

Batty G D, Li Q, Huxley R et al. Oral disease in relation to future risk of dementia and cognitive decline: prospective cohort study based on the Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified-Release Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE) trial. Eur Psychiatry 2013; 28: 49–52.

Yamamoto T, Kondo K, Hirai H, Nakade M, Aida J, Hirata Y . Association between self-reported dental health status and onset of dementia: a 4-year prospective cohort study of older Japanese adults from the Aichi Gerontological Evaluation Study (AGES) Project. Psychosom Med 2012; 74: 241–248.

Okamoto N, Morikawa M, Tomioka K, Yanagi M, Amano N, Kurumatani N . Association between tooth loss and the development of mild memory impairment in the elderly: the Fujiwara-kyo Study. J Alzheimers Dis 2015; 44: 777–786.

Kaye E K, Valencia A, Baba N, Spiro A, 3rd, Dietrich T, Garcia R I . Tooth loss and periodontal disease predict poor cognitive function in older men. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58: 713–718.

Arrive E, Letenneur L, Matharan F et al. Oral health condition of French elderly and risk of dementia: a longitudinal cohort study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2012; 40: 230–238.

Stewart R, Stenman U, Hakeberg M, Hagglin C, Gustafson D, Skoog I . Associations between oral health and risk of dementia in a 37-year follow-up study: the prospective population study of women in Gothenburg. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63: 100–105.

Tsakos G, Watt R G, Rouxel PL, de Oliveira C, Demakakos P . Tooth loss associated with physical and cognitive decline in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63: 91–99.

Cerutti-Kopplin D, Feine J, Padilha D et al. Tooth Loss Increases the Risk of Diminished Cognitive Function A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JDR Clin Transl Res 2016; 1: 10–19.

Wu B, Fillenbaum G G, Plassman B L, Guo L . Association Between Oral Health and Cognitive Status: A Systematic Review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016; 64: 739–751.

Public Health England. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention (third edition). London: PHE, 2014. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/delivering-better-oral-health-an-evidence-based-toolkit-for-prevention (accessed November 2017).

American Academy of Periodontology Task Force. American Academy of Periodontology Task Force Report on the Update to the 1999 Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol 2015; 86: 835–838.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of Carly Tutti of Public Health England during a workshop in preparation for this paper. We further acknowledge the overall support of Public Health England, the Faculty of Dental Surgery of The Royal College of Surgeons of England and The British Dental Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table 1

Cohort and case-control studies: Is dementia (including cognitive decline) a risk factor for poor oral health? (PDF 174 kb)

Supplementary Table 2

Cohort and case-control studies: Is poor oral health a risk factor for developing dementia (including cognitive decline)? (PDF 216 kb)

Supplementary Table 3

Systematic review on tooth loss and periodontal disease and cognitive impairment (PDF 92 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Daly, B., Thompsell, A., Sharpling, J. et al. Evidence summary: the relationship between oral health and dementia. Br Dent J 223, 846–853 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.992

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.992

This article is cited by

-

Opportunistic health screening for cardiovascular and diabetes risk factors in primary care dental practices: experiences from a service evaluation and a call to action

British Dental Journal (2023)

-

The effect of missing teeth on dementia in older people: a nationwide population-based cohort study in South Korea

BMC Oral Health (2019)

-

Caries prevalence and dental health of 8–12 year-old children in Damascus city in Syria during the Syrian Crisis; a cross-sectional epidemiological oral health survey

BMC Oral Health (2019)

-

Understanding and tackling oral health inequalities in vulnerable adult populations: from the margins to the mainstream

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Poor Oral Health and Its Neurological Consequences: Mechanisms of Porphyromonas gingivalis Involvement in Cognitive Dysfunction

Current Oral Health Reports (2019)