Key Points

-

Provides results of the first study to investigate the incidence of social media Fitness to Practise (FtP) cases investigated by the GDC since it established social media guidelines in 2013.

-

Demonstrates that most of the complaints were made against dental nurses and the most common type of complaint was in relation to inappropriate Facebook comments.

-

Suggests that social media awareness training should be an integral part of undergraduate and CPD training.

Abstract

Introduction Since 2013, all General Dental Council (GDC) registrants' online activities have been regulated by the GDC's social media guidelines. Failure to comply with these guidelines results in a Fitness to Practise (FtP) complaint being investigated.

Aims This study explores the prevalence of social media related FtP cases investigated by the GDC from 1 September 2013 to 21 June 2016.

Method Documentary analysis of social media related FtP cases published on the GDC's website was undertaken. All cases that met the study's inclusion criteria were analysed using a quantitative content analysis framework.

Findings It was found that 2.4% of FtP cases published on the GDC website during that period were related to breaches of the social media guidelines. All of the cases investigated were proven and upheld. Most of those named in the complaints were dental nurses and the most common type of complaint was inappropriate Facebook comments.

Conclusions The low incidence rate should be interpreted with caution, being illustrative of the types of issues that might arise rather than the volume. The GDC will need to remain vigilant in this area and ensure that social media awareness training is an active part of CPD for all the dental team.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Digital technologies are having an undeniable impact on health. Countless websites, blogs, vlogs, and apps have transformed the health behaviours of the public by providing them with more health information than was previously available to them.1,2,3 For healthcare professionals, the advance of social media has also transformed their role and professional responsibilities in society. Social media is defined as 'internet-based channels that allow users to opportunistically interact and selectively self-present, either in real-time or asynchronously, with both broad and narrow audiences who derive value from user-generated content and the perception of interaction with others'.4 This commonly includes such social networking sites as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. A high proportion of healthcare professionals use social media for personal use.5,6,7 Others consider social media, especially Facebook and Twitter, as a tool for professional development, as a means of accessing information, marketing practices and services, job opportunities, as well as sharing or adding your opinion on issues of interest to you and to other like-minded individuals online.8,9 However, other social media research has been conducted that has implications for the profession and the patient-practitioner relationship. Much of this research has highlighted instances where healthcare professionals' social media activities and their content may be damaging the social contract that exists between society and health professionals,10,11,12,13,14,15 such as having an online relationship with patients,16 breaching patient confidentiality in various postings17 and writing disrespectful comments about colleagues and employers.18,19 For instance, in a sample of 880 medical students in Australia,20 34% reported to having unprofessional content in their social media accounts, for example, evidence of being intoxicated(34.2%), illegal drug use(1.6%), posting patient information(1.6%), and depictions of an illegal act(1.1.%). Unsurprisingly, many professional bodies have developed social media guidelines for its registrants in order to clearly delineate the professional responsibilities and expectations regarding social media behaviour by healthcare professionals.21,22,23,24,25

In September 2013, the GDC published social media guidelines for all its registrants. As a result, inappropriate social media activities by a GDC registrant was deemed one of the grounds on which the public can make a complaint to the GDC about their Fitness to Practise (FtP). These guidelines were revised in June 2016 with respect to registrants' activity on 'a number of internet-based tools including, but not limited to, blogs, internet forums, content communities and social networking sites such as Twitter, YouTube, Facebook, LinkedIn, GDPUK, Instagram and Pinterest'21 In light of the recent revisions to the GDC's social media guidelines it was considered timely to investigate the incidence of social media-related FtP cases that have been investigated by the GDC. How many FtP cases have been brought before the GDC due to infringements of the social media guidelines? Was the revision of the 2013 guidelines prompted by a large volume of FtP cases since the establishment of the guidelines and a resultant need to revise and strengthen the existing guidelines? Or, does it merely reflect efforts by a regulatory body to be proactive regarding this rapidly changing dimension to contemporary professional practice?

Aims and objectives

This study was interested in examining the impact that social media is having on dental professionalism. It adjudicated this by examining the number and content of FtP cases relating to social media and the sanctions imposed by the GDC from 1 September 2013 to 21 June 2016. These dates were chosen because they captured two key milestones in the GDC's regulation of the social media behaviour of its registrants: when the guidelines were first established and when they were revised.

This study had two objectives:

-

To identify the number of FtP cases concerning social media infringements investigated by the GDC from 1 September 2013 to 21 June 2016

-

To quantitatively examine the nature of each of the cases and identify pertinent themes and underlying patterns of these online professional lapses.

This study provides numerical data on the incidence of social media-related FtP cases being considered by the various FtP committees of the GDC. This quantitative data can act as a baseline for official social media complaints received by the GDC. This in turn will enable us to plot and chart changes in this practice in the years to come. Moreover, by quantitatively analysing the details of each cases involved, we will gain insight into the types of online professional lapses GDC registrants have made. This detailed information can give us important indicators as to the possible further/future training and professional support registrants need in order to maintain acceptable online professional practice. Overall, it is hoped that this information will stimulate wider debates about social media practices among GDC registrants; not only among dentists but also the wider dental team. This debate may lead to a greater appreciation of and knowledge of the guidelines and facilitate more vigilance in their personal practice.

Method

Under the Dentist Act (1984) dentists in the UK and their fitness to practise are regulated by the GDC.26 Since 2007, the GDC have taken on the responsibility for regulating clinical dental technicians, dental hygienists, dental technicians, dental therapists and orthodontic therapists.27

GDC registrants can expect to have to defend themselves against a Fitness to Practise complaint if they have committed a criminal offence, if a public complaint has been received that their professional conduct has contravened one or more of the nine Standards for Practice (2005)(this includes social media guidelines), or the disclosure that the health of a GDP or some aspect of their professional performance puts patients at risk.28 Once a complaint has been received, it is triaged within ten days to determine if it meets the investigation test. If there are sufficient grounds for a full enquiry, the case is assessed where it can be considered by an interim orders committee as case examiners are appointed to prepare the case for the Practice Committee. There the decision is made as to whether the GDC registrant's fitness to practise has been impaired and the class of sentence to be passed down. A flow chart for how the FtP mechanism operates in the GDC is outlined in Figure 1.

Records of FtP complaints investigated by the GDC are recorded on the GDC website. These publically available case reports were the source material used in this study. Using the GDC website of published FtP cases is a reliable data set as it is the responsibility of the GDC to publish all FtP cases and committee decisions in a timely manner in accordance with rule 29 (3) of the General Dental Council (Fitness to Practise) Rules Order of Council 2006.27 This type of documentary analysis of the GDC or any other regulatory body's archive record of complaints is common practice among researchers interested in professional regulation.27,29,30,31 No ethical application was made for this study as the reports are publically available on the GDC website.

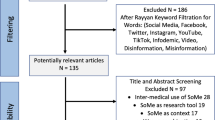

The research consisted of two stages: first, a search was conducted of all the GDC's online FtP records from 1 September 2013 to 21 June 2016. All cases pertaining to social media FtP cases were identified, logged, and printed off. Second, these social media FtP cases were read closely and subjected to content analysis framework. Content analysis is 'an approach to the analysis of documents and texts that seeks to quantify content in terms of pre-determined categories and in a systematic and replicable manner'.32 A key tool to content analysis is the design of the coding schedule. This schedule contains 'all the data relating to the item being coded'.32 The use of coding schemes ensures that the study is replicable and the sampling methods are transparent.32 In this study, each case was coded according to the following criteria: GDC reference number; brief description of the case; category of FtP case; admission at hearing; evidence of remediation; outcome of the decision; source of complaint; gender of person named in the complaint; professional occupation of person named in the complaint; and hearing outcome. Though the subjects of the complaints are named in the case reports, this research will de-identify the registrants for the purpose of this publication, with alternative handles being used instead, for example, GDC Registrant A, GDC Registrant B etc.

Findings

From 1 September 2013 to21 June 2016 – 253 FtP cases were published on the GDC website. From this initial data set, six cases were found to involve social media FtP infringements. Table 1 documents the FtP cases recorded from 1 September 2013 to 21 June 2016. In the three years since the social media guidelines were instituted only six cases (or 2.4% of the sample) were investigated in relation to unprofessional social media activities. Instances of FtP cases related to social media first emerge in 2015. Table 2 reveals the summary details of the GDC registrants named in these social media related FtP cases. Even with this small sample, the influence of gender and professional category exists. More social media related FtP cases were brought against women than men and dental nurses were the most prevalent occupation category in this sample. The most common type of social media infringement were unprofessional and offensive postings on Facebook including one instance of a dentist asking to look up a patient on Facebook during a patient consultation. (Table 3, Table 4). The sample also revealed one case of using social media to advertise professional services that they were not eligible to perform and one case of breaching patient confidentiality online (Table 4). The leading outcomes for the FtP hearings was that of suspension or reprimand (Table 5).

Discussion

Since 2013, the GDC has instituted social media guidelines for all registrants to adhere to. Living in a jurisdiction where there are clearly delineated guidelines about social media is beneficial. By bringing social media into the professional standards and guidelines, the GDC are firmly locating social media as another aspect of one's life and lifestyle to which they must be self-circumspect and discerning. This study has found that only 2.4% of FtP cases published on the GDC website were social media-related. For those found to have broken these guidelines these cases serve to reaffirm the professional values of the profession and 'the professional ideal of individual accountability or self-governance'33 in relation to social media. Since all the complaints were proven and sanctions given we can say that the GDC does take the social media behaviour of its members seriously and acts accordingly. However, this low figure needs to be interpreted with caution as it could indicate a problem with underreporting from the public and among fellow professionals. The cases should be regarded as the tip of the iceberg of what occurs in practice, illustrative of the types of issues that might arise but not the volume.

While the sample size is small, certain trends can be commented upon. The study indicated that the most common route through which registrants broke the GDC social media guidelines was via inappropriate Facebook postings. Though there has been recent discussion about the appropriateness of the GDC adjudicating on the private Facebook comments of GDC registrants,34,35 the Practice Committee in each case deemed the content of their postings to be unprofessional and offensive in nature. Individual cases were also found to show how social media was used to break patient confidentiality and compromise the professional distance and relationship that should exist between a dental professional and their patient. In all of these cases social media acted as a potent vehicle through which unprofessional attitudes and values become apparent. In this way, the GDC's social media guidelines are serving a public value in maintaining the social contract and upholding the reputation of the dental profession. Most of the complaints were brought against and proven against dental nurses. Undoubtedly, the actions of a small minority do not in itself suggest a fundamental problem with the professionalism of dental nurses. However, it does raise the question about whether social media awareness training is part of dental nurse's professional education. The findings of this study would suggest that social media training is important for all members of the dental team, both as part of their initial training but also their continuing professional development (CPD).

It is important to state that this study does not claim to constitute a complete analysis of or representation of the scale of social media breaches among GDC members. Rather its purpose is to start the process of documenting those that have been reported to FtP since the guidelines first appeared in 2013. There is also value in re-stating that the number of FtP cases published on the GDC website is not a contemporaneous record. It is merely a snapshot in time of the cases that the Professional Conduct Committee can practically schedule and progress depending on members availably and within due process. While the current number of social media-related FtP cases is very low, the coming years may in fact show an increase in the number of social media related FtP cases. Many studies have documented how current healthcare students display a degree of ambiguity when it comes to interpreting the professionalism of their online actions.36 For instance, healthcare professional students are aware of the importance of being professional online but don't think it applies to them until they graduate.37 Other students consider their social media as a private activity and do not think it appropriate for their social media habits to be discussed or taught as part of their professional education.38 Another study found that there was a noted 'disconnect between voiced concerns and a lack of any directed action to secure privacy' on Facebook. This was due to their opinion that it was 'tedious' to change/monitor privacy settings, because they self-reported that they didn't have anything unprofessional on their Facebook page, or that they didn't know how to change the privacy settings.39 These findings suggest that the next wave of graduates may struggle with complying with all the social media guidelines set out by the GDC. The baseline data provided by this study will help us to track any future trends in social media complaints.

Conclusions

This analysis of FtP cases relating to the GDC's social media guidelines supports the assumption that social media can be a vehicle for unprofessionalism. Though the number of actual cases was very low for the study (six cases), it is reassuring that the GDC investigates complaints that are made about the social media behaviour of its members. The study also shows that the revisions of the 2013 guidelines in June 2016 was not precipitated by an increase in social media complaints per se, but rather an indication of the efforts of the GDC to remain vigilant and pro-active in regulating the actions of their registrants.

Social media will continue to shape the institution of healthcare and social and professional interactions between practitioners and the public in the years to come. It is important that dental educators look on social media activity as another aspect of professionalism and incorporate social media awareness training as part of its overall programme of teaching professionalism. It is also incumbent on the GDC to encourage social media training as part of lifelong learning and continued professional development of its registrants.

References

Lupton D . The digitally engaged patient: Self-monitoring and self-care in the digital health era. Soc Theory Med 2013; 11: 256–270.

Hardey M . Public health and Web 2.0. J R Soc Promot Health 2008; 128: 181–189.

Korda H, Itani Z . Harnessing Social Media for Health promotion and Behavioural Change. Health Promot Pract 2013; 14: 15–23.

Carr C T, Hayes R A . Social media: Defining, developing, and divining. Atlantic Jr Comm 2015; 23: 46–65.

Usher K, Woods C, Glass N et al. Australian health professionals' student use of social media. Collegian 2014; 21: 95–101.

Ranschaert E R, Van Ooijen P M A, McGinty G B, Parizel P M . Radiologists' usage of Social Media: Results from the RANSOM Survey. J Digit Imaging 2016; 29: 443–449.

Kenny P, Johnson I . Social media use, attitudes, behaviour and perceptions of online professionalism among dental students. Br Dent J 2016; 221: 651–655.

Chretien K C, Tuck M G, Simon M, Singh L O, Kind T . A Digital Ethnography of Medical Students who Use Twitter for Professional Development. J Gen Intern Med 2015; 30: 1673–1680.

Alsobayel H . Use of social media for Professional Development by Health Care Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Web-Based Study. JMIR Med Educ 2017; 2: e15.

Neville P . Clicking on professionalism? Thoughts on teaching students about social media and its impact on dental professionalism. Euro J Dent Educ 2015; 20: 55–58.

Neville P, Waylen A . Social media and dentistry: Some reflections on eprofessionalism. Br Dent J 2015; 218: 475–478.

DeCamp M, Koening T W, Christolm M S . Social Media and Physicians' Online Identity Crisis. JAMA 2013; 30: 581–582.

Wilson R, Ranse J, Cashin A, McNamara P . Nurses and Twitter: the good, the bad and the reluctant. Collegian 2014; 21: 111–119.

Ferguson C . It's time for the nursing profession to leverage social media. J Adv Nurs 2013; 69: 745–747.

McKee R . Ethical issues in using social media for health and health care research. Health Policy 2013; 110: 298–301.

Nyangeni T, du rand S, van Rooyen D . Perceptions of nursing students regarding responsible use of social media in the Eastern Cape. Curationis 2015; 38: 1496–1504.

Thompson C . Facebook-cautionary tales for nurses. Nurs N Z 2010; 16: 26.

Chretien K C, Azar J, Kind T . Physicians on twitter. JAMA 2011; 305: 566–568.

Hall M, Hanna L A, Huey G . Use and views on social networking sites of pharmacy students in the United Kingdom. Am J Pharm Educ 2013; 77: 9.

Barlow C J, Morrison S, Stephens H O, Jenkins E, Bailey M J, Pilcher B . Unprofessional behaviour on social media by medical students. Med J Aust 2015; 203: 439.

General Dental Council. Guidance on using social media. 2016. Available at https://www.gdc-uk.org/api/files/Guidance%20on%20using%20social%20media.pdf (accessed August 2017).

Royal College of General Practitioners. Social Media Highway Code. 2013 Available at http://www.rcgp.org.uk/-/media/Files/Policy/A-Z-policy/RCGP-Social-Media-Highway-Code.ashx?la=en (accessed August 2017).

General Medical Council. Doctor's use of social media. 2013. Available at http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/21186.asp (accessed August 2017).

The British Association of Social Workers. BASW's Social Medical Policy. 2013. Available at https://www.basw.co.uk/resource/?id=1515 (accessed March 2017).

Nursing and Midwifery Council. Social media guidance. Our guidance on the use of socialmedia. 2016. Available at https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/guidance/social-media-guidance/ (accessed August 2017).

HMSO. Dentists Act 1984. Available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1984/24 (accessed August 2017).

Gallagher C, De Souza AI . A retrospective analysis of the GDC's performance against is newly-approved fitness to practise guidance. Br Dent J 2015; 219: 1–5.

General Dental Council. Fitness to Practise. Information online at https://www.gdc-uk.org/professionals/ftp-prof (accessed August 2016).

Singh P, Mizrahi E, Korb S . A five year review of cases appearing before the General Dental Council's Professional Conduct Committee. Br Dent J 2009; 206: 217–223.

Gallagher C, Greenland V A M, Hickman A C . Eram, ergo sum? A 1year retrospective study of General Pharmaceutical Council fitness to practise hearings. Int J Pharm Pract 2015; 23: 205–211.

Harris R, Slater K . Analysis of cases resulting in doctors being erased or suspended from the medical register: Report prepared for the General Medical Council. 2015. Available at http://www.gmc-uk.org/Analysis_of_cases_resulting_in_doctors_being_suspended_or_erased_from_the_medical_register_FINAL_REPORT_Oct_2015.pdf_63534317.pdf (accessed August 2017).

Bryman A . Social Research methods. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Case P . The good, the bad and the dishonest doctor: the General Medical Council and the 'redemption model' of fitness to practise. Leg Stud 2011; 31: 591–614.

Affleck P, Macnish K . Should 'fitness to practise' include safeguarding the reputation of the profession? Br Dent J 2016; 221: 545–546.

Holden A C L . Paradise Lost; the reputation of the dental profession and regulatory scope. Br Dent J 2017; 222: 239–241.

Chretien K C, Goldman E F, Beckman L, Kind T . It's Your Own Risk: Medical Students' Perspective on Online Professionalism. Acad Med 2010; 85: 568–571.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Neville, P. Social media and professionalism: a retrospective content analysis of Fitness to Practise cases heard by the GDC concerning social media complaints. Br Dent J 223, 353–357 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.765

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.765

This article is cited by

-

Preserving professional identities, behaviors, and values in digital professionalism using social networking sites; a systematic review

BMC Medical Education (2021)

-

Hashtag, like or tweet: a qualitative study on the use of social media among dentists in London

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Conflicting demands that dental professionals experience when using social media

BDJ Team (2020)

-

Perceptions of e-professionalism among dental students: a UK dental school study

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

How accessible are you? A hospital-wide audit of the accessibility and professionalism of Facebook profiles

British Dental Journal (2019)