Key Points

-

Improves understanding of complexities of treating hypodontia patients with implants.

-

Provides an understanding of multidisciplinary service development.

-

Discusses achievable treatment outcomes for hypodontia implant patients.

Abstract

Background Implant treatment to replace congenitally missing teeth often involves multidisciplinary input in a secondary care environment. High quality patient care requires an in-depth knowledge of treatment requirements.

Aim This service review aimed to determine treatment needs, efficiency of service and outcomes achieved in hypodontia patients. It also aimed to determine any specific difficulties encountered in service provision, and suggest methods to overcome these.

Methods Hypodontia patients in the Unit of Periodontics of the Scottish referral centre under consideration, who had implant placement and fixed restoration, or review completed over a 31 month period, were included. A standardised data collection form was developed and completed with reference to the patient's clinical record. Information was collected with regard to: the indication for implant treatment and its extent; the need for, complexity and duration of orthodontic treatment; the need for bone grafting and the techniques employed and indicators of implant success.

Conclusion Implant survival and success rates were high for those patients reviewed. Incidence of biological complications compared very favourably with the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multidisciplinary care is well established in many clinical fields. With particular relevance to dentistry are the multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) working in head & neck cancer and cleft services. Since their inception these specialist teams of professionals have helped to ensure provision of the highest standards of care.1

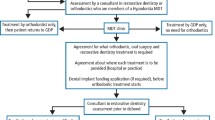

Patients who have developmentally missing teeth have complex needs that may benefit from a multidisciplinary approach. The successful implementation of multidisciplinary care requires effective organisation, informed by knowledge of typical (and atypical) patient pathways that, in themselves, will reflect the clinical needs of the patients and the resources and limitations of the particular healthcare provider. The multidisciplinary hypodontia clinics within the particular NHS referral centre reviewed in this article have been in existence for more than 15 years. This review seeks to uncover some of the issues present and assumes that the outcomes will be of interest to other providers of similar care. The use of implants in patients with hypodontia may offer significant advantages but can also present particular challenges; hence these patients are the focus of interest for this review. Patients who, after multidisciplinary input, opted for tooth replacement with bridgework were not included in this review.

Clinical outcome recording is key to measuring the success of any treatment approach. As Yap and Klindeberg found in 2009, literature examining implant outcomes in hypodontia patients is scarce. These authors were able to include only 12 articles in their critical review of the literature pertaining to implants in hypodontia and ectodermal dysplasia patients, none of which were case- or randomised-case controlled studies.2

Therefore, this review aimed to address the following questions:

-

What were the multidisciplinary treatment needs of hypodontia patients accepted for implant treatment?

-

How well did the organisation of this care function, in terms of facilitating the most efficient and evidence-based patient pathways?

-

What were the outcomes of treatment in terms of:

-

Implant survival

-

Implant success

-

Aesthetic acceptability.

Materials and methods

Hypodontia patients in the Unit of Periodontics of the Scottish referral centre under consideration, who had implant placement and fixed restoration, or review completed over a 31 month period, were included. A standardised data collection form was developed and completed with reference to the patient's clinical record. The only exclusion criterion was the absence of sufficient detail regarding date of implant surgery, implant position, type of implant (submerged vs. transmucosal), timing of second stage surgery, loading or final restoration placement.

Information was collected with regard to:

-

The indication for implant treatment and its extent

-

The need for, complexity and duration of orthodontic treatment, including the interface with other specialties

-

The need for bone grafting and the techniques employed

-

Indicators of implant success.

As the data pertaining to implant success was collected at subsequent review appointments, not all of the restored implants had this data present. These implants were still included in the review where other relevant data was available.

In order to assess bone loss around an implant a 'baseline' radiograph taken immediately post placement and one taken at follow-up review examination were required. All radiographs for bone level assessments were periapicals taken with Rinn holders and F Speed film. Bone levels were measured from baseline and follow-up radiographs. Implants were regarded as positive for bone loss if it was judged there had been >2 mm bone loss on the rough surface of the implant from time of initial placement.3 Radiographs were divided between two calibrated assessors, for evaluation, neither of whom had been involved in treatment of the patients.

The 'Pink Esthetic Score' (PES) system used to assess the appearance of the peri-implant soft tissues was that developed by Fürhauser et al. in 20054. This system is designed to be used in single tooth restorations only. As the authors were unable to identify a similar tool for the objective aesthetic assessment of implant supported bridgework, the PES system was also used to assess these restorations in the study. The allocation of a PES score was only possible where post-restoration photographs were available. Patients with photographs available were randomly divided between the two examiners for assessment following calibration. One of the limitations of any aesthetic assessment tool is the potential for bias. Although the authors acknowledge this potential, no members of the study team who undertook the aesthetic assessments had been involved in provision of implant treatment. Where PES score judgements were felt to be uncertain they were discussed and an outcome agreed.

Results

It was possible to collect data for 32 hypodontia patients; 77 implants were placed. Of these, review data was available for 24 of 32 patients receiving implant treatment. The remaining eight patients had either failed to attend their review appointments or had not yet been reviewed.

The minimum age at implant placement was 15 years, maximum age 52 years. Mean age at implant placement was 23 years. Fifty-six percent of patients treated were male, 44% female.

Forty-one percent of patients receiving treatment were missing only one tooth. The average number of missing teeth was three. The most commonly replaced tooth was the maxillary lateral incisor (36%, n = 28). The maxillary canine was the second most common tooth replacement site (21%, n = 16).

Adjunctive orthodontics

As demonstrated in Table 1, for the majority of patients there was a joint orthodontic-restorative assessment before the patient commencing treatment. Orthodontic treatment usually consisted of upper and lower fixed appliances. Orthodontic therapy was a mean of 31 months (minimum 9 months, maximum of 71 months).

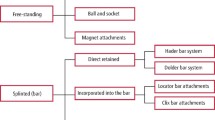

Adjunctive bone augmentation

The various approaches to bone augmentation employed are set out in Table 2. Bone grafting was required in 53% of patients, (n = 17). Three patients required pre-implant autogenous bone grafts harvested from the iliac crest. Forty-eight percent (n = 18) of implants that required grafting were placed in these three patients. Seven patients required block grafts harvested from intra-oral sites. Twenty-six percent of total implants placed (n = 10) were in these patients.

Where grafts were placed before implant placement, the mean time separating the two procedures was 27 weeks. However, there was a significant range. The minimum time between the grafting procedure and implant placement was 17 weeks.

Implant survival and success

As stated, review data was not available for all patients. Eight patients had either failed to attend their review appointments or had not yet been reviewed at the time this review was undertaken. Therefore, the success data (bone loss, periodontal probing depths and bleeding on probing) presented in Table 3 relates to 63 implants in 24 patients. The mean time from implant placement to the latest available review data was 2 years 7 months (min 5 months, max 9 years and 1 month).

Aesthetic analysis

Aesthetic analysis was possible for approximately 52% of implants (21 patients). For the remainder, no clinical photographs were available. The majority of implants (83%) (15 patients) were found to have aesthetically acceptable or favourable restorations (see Table 4). Six patients had unacceptable aesthetic outcomes.

Discussion

Orthodontics

Three quarters of patients required orthodontic treatment before the implant/restorative phase. Timing orthodontic treatment so that it is completed just as craniofacial growth has stopped represents the ideal; provided implant placement can proceed shortly thereafter. This minimises the risk of orthodontic relapse. Should relapse occur further orthodontic therapy before implant surgery may be necessary to correct malpositioned teeth, or more commonly roots, converging into the space for implant placement. The requirement for multiple courses of orthodontic therapy was found to have significantly lengthened the treatment process for a number of the patients studied. Adequate, where possible fixed, orthodontic retention is essential to prevent this relapse. Where fixed retention is not possible, retainer wear is critical if patients wish to have implant treatment in the future. Patients must be fully consented in this regard before commencing any orthodontic therapy. It is not current practice to refuse repeat orthodontics for hypodontia patients who have not fully cooperated with retainer wear before implant treatment; however this may change in the future. Hypodontia, and in particular appearance concerns, have been shown to have a significant effect on oral health related quality of life.5 This may necessitate commencing treatment earlier in these patients and accepting that further orthodontic therapy may be necessary at a later date.

A restorative assessment before orthodontic debond may minimise delays to implant treatment, or compromising implant results. Around one fifth of patients jointly assessed before debond were found to require additional orthodontic therapy. However, often restorative review was arranged by orthodontists, in the knowledge that treatment had not yet been completed, to confirm finer details of the treatment plan and patient consent to the restorative phase of treatment.

In one female patient implant placement had taken place at age 15. These implants were placed in mandibular canine regions and not definitively restored until 18 months following placement. From the Thilander growth studies, we know that growth in the anterior mandible from ages 16–31 has been shown to be minimal both in terms of bone height and arch width change.6 This placement did not appear to have had any negative outcome for the patient.

Bone grafting

Staged bone grafting was required in 53% of patients before implant placement. It is generally accepted that guided bone regeneration with deproteinised bovine bone matrix, or an alloplastic substitute, is likely to achieve a maximum increase in alveolar bone width of 4.5mm. (Buser et al.7). For patients in which the deficiency is greater, usually block bone grafting techniques are preferable.8 Patients with multiple missing teeth, replaced with fixed restorations aiming to achieve favourable gingival aesthetics, are more likely to require the larger amounts of bone. These volumes are generally harvested from the iliac crest. This was found to be the case in our severe hypodontia patients.

Timing of treatment

The mean time delay between bone grafting procedures and implant placement was approximately six months. For four patients (seven implants), implant placement occurred greater than six months after graft surgery. Most commonly it was availability of clinical appointments and correspondence between involved specialties which was responsible for the variation and longer averages in treatment time, rather than clinical decision making. Volumetric changes in grafts months after placement have been shown to be significant.9 The most notable volumetric width change has been found to occur in the 1–3 month post-operative period.10 The optimal time for implant placement post grafting is therefore generally regarded as between 3–6 months. This allows for integration and stabilisation of the graft, avoiding unnecessary volumetric decrease. Practice in this field is evolving, and is likely to have changed over the period studied.

Implant treatment can be a lengthy process involving multiple stages and multidisciplinary interaction from planning to surgical placement. The mean time patients took from initial implant assessment (formal) to implant placement was 12 months. Factors which increased the duration of time between initial planning and implant placement were need for cone beam CT, hospital appointment booking difficulties, need for further orthodontic treatment, bone grafting, and suboptimal oral hygiene or periodontal condition requiring Hygienist input. In addition to this, implant placement to final restoration was found to take a mean of 12 months. The long duration of implant treatment should clearly be explained to patients as part of the ongoing consent process.

Implant survival and success

Implant survival rates compare favourably to other literature on survival (96% implants). A review carried out by Berglundh et al. examining longitudinal studies of up to 5 years, observed an implant survival rate of 97.5% up to the second stage of surgery.11 However, the variable follow-up period and number of implants not reviewed makes comparison of survival rates difficult.

From the data available none of the implants studied exhibited pathological bone loss. This is favourable compared to a recent meta-analysis, which found the prevalence of bone loss to be around 22% of implants.12 The criteria used to determine bone loss and the length of follow up, are noted as variable in the literature. 2D assessment of bone loss on periapical radiographs, as most commonly described and used in this study, may be flawed. Labial onlay grafts are more likely to be subject to short-medium term labial bone resorption than the original recipient bone site. The 2D assessment of bone levels on a peri-apical radiograph would not demonstrate this loss of labial bone surface. Therefore, this type of bone loss would not be shown by this method of assessment.

The incidence of other biological complications in the reviewed cohort was also low. No standardised guidelines for clinical or radiographic review were in use at the time of this review. Recording of bone loss or other biological complications was variable, with this data frequently not recorded in the clinical notes. However, the most appropriate means of monitoring the health of the peri-implant tissues has been a controversial topic in the past and the findings in this review may represent evolving opinion and confusion in this area.13

Photographs were available for 52% of implants (n = 40) (21 patients). This meant implant restoration aesthetic analysis was not possible in every case. Given the importance of final aesthetics on implant success, it is important to document aesthetic outcomes. The suitability of PES scoring for determining aesthetic success for restorations has been confirmed in a number of studies.14,15,16,17,18 There are, however, limitations. In particular, the PES system is an implant-based analysis and does not take into account overall patient satisfaction, or smile line. This is a potential avenue for further study.

Conclusion

-

Implant survival and success rates were high for those patients reviewed. Incidence of biological complications compared very favourably with the literature

-

This review highlighted a number of challenges to high quality implant service provision for hypodontia patients. In particular:

-

Difficulty in ensuring effective communication between the specialties involved ensuring treatment is coordinated effectively

-

Importance of standardised review protocol to ensure implants are followed up and maintained as required.

Since this review was carried out a number of changes have been made to the design of the existing multidisciplinary hypodontia service to improve the coordination of multidisciplinary care and to standardise follow up of patients.

Implant dentistry is a rapidly evolving field. Review and modification of practice in keeping with current knowledge and best practice is critical to ensure a high standard of care for patients. Repeat review following these service changes will be essential to continue improvements to service.

Implant treatment in the examined cohort has been found to be a lengthy process involving attendance at multiple appointments, with involvement of a variety of specialties. In order for treatment to proceed as efficiently as possible patient cooperation with appointment attendance and treatment is essential. Patients must be encouraged to take ownership and responsibility for this throughout the treatment pathway.

The significant challenge in organising multidisciplinary treatment, so that each stage proceeds smoothly from the previous one, can be appreciated from some of the outcomes of this review. Such challenges are likely to apply in any large institution. Although clinicians are likely to be aware of the difficulties on a day to day basis, the review process helps to quantify the problem and provide evidence for change.

References

Epstein N E . Multidisciplinary in-hospital teams improve patient outcomes: A review. Surg Neurol Int 2014; 5: 295–303.

Yap A K, Klinegerg I . Dental implants in patients with ectodermal dysplasia and tooth agenesis: a critical review of the literature. Int J Prosthodont 2009; 22: 268–276.

Misch C E, Perel M L, Wang H L et al. Implant success, survival and failure: the International Congress of Oral Implantologists (ICOI) Pisa consensus conference. Implant Dent 2008; 17: 5–15.

Fürhauser R, Florescu D, Benesch T, Haas R, Mailath G, Watzek G . Evaluation of soft tissue around single-tooth implant crowns: the pink esthetic score. Clin Oral Impl Res 2005; 16: 639–644.

Anweigi L, Allen P F, Ziada H . The use of the Oral Health Impact Profile to measure the impact of mild, moderate and severe Hypodontia on oral health-related quality of life in young adults. J Oral Rehabil 2013; 40: 603–608.

Thilander B . Dentoalveolar development in subjects with normal occlusion. A longitudinal study between the ages of 5 and 31 years. Eur J Orthod 2009; 31: 109–120.

Buser D A, Bragger U, Lang N, Nyman S . Regeneration and enlargement of jaw bone using guided tissue regeneration. Clin Oral Implants Res 1990; 1: 22–32.

Schwarz F, Rothamel D, Herten M et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of guided bone regeneration at a dehiscence-type defect using different barrier membranes: an experimental study in dogs. Clin Oral Implants Res 2008; 19: 402–415.

Dasmah A, Thor A, Ekestubbe A, Sennerby L, Rasmusson L . Particulate vs. block bone grafts: Three-dimensional changes in graft volume after reconstruction of the atrophic maxilla, a 2-year radiographic follow-up. J Cranio Maxillofac Surg 2012; 40: 654–659.

Nyström E, Legrell P.E, Forssell A, Kahnberg K E . Combined use of bone grafts and implants in the severely resorbed maxilla. Postoperative evaluation by computed tomography. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1995; 24: 20–25.

Berglundh T, Persson L, Klinge B . A systematic review of the incidence of biological and technical complications in implant dentistry reported in prospective longitudinal studies of at least 5 years. J Clin Periodontol 2002; 29: 197–212.

Derks J, Tomasi C . Peri-implant health and disease. A systematic review of current epidemiology. J Clin Periodontol 2015; 42: 158–171.

Todescan S, Lavigne S, Kelekis-Cholakis A . Guidance for the maintenance care of dental implants: clinical review J Can Dent Assoc 2012; 78: 107.

Cosyn J, De Bruyn H, Cleymaet R . Soft tissue preservation and pink aesthetics around single immediate implant restorations: a 1-year prospective study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2013; 15: 847–857.

Dierens M, De Bruecker E, Vandeweghe S, Kisch J, de Bruyn H, Cosyn J . Alterations in soft tissue levels and aesthetics over a 16–22 year period following single implant treatment in periodontally-healthy patients: a retrospective case series. J Clin Periodontol 2013; 40: 311–318.

Gallucci G O, Grutter L, Nedir R, Bischof M, Belser U C . Esthetic outcomes with porcelain-fused-to-ceramic and all-ceramic single implant crowns: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Implants Res 2011; 22: 62–69.

Hof M, Pommer B, Strbac G D, Suto D, Watzek G, Zechner W . Esthetic evaluation of single-tooth implants in the anterior maxilla following autologous bone augmentation. Clin Oral Implants Res 2013; 24: 88–93.

Raes F, Cosyn J, De Bruyn H . Clinical, aesthetic, and patient-related outcome of immediately loaded single implants in the anterior maxilla: a prospective study in extraction sockets, healed ridges, and grafted sites. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2013; 15: 819–835.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burns, B., Grieg, V., Bissell, V. et al. A review of implant provision for hypodontia patients within a Scottish referral centre. Br Dent J 223, 96–99 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.623

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.623

This article is cited by

-

A cross sectional study of dental implant service provision in British and Irish dental hospitals

British Dental Journal (2019)