Key Points

-

This study provides an insight into the career satisfaction and work-life balance of orthodontists in the UK/ROI.

-

The study identified those major factors which significantly affect career satisfaction and work-life balance.

-

Recommendations are made for measures which professional bodies could consider in order to enhance career satisfaction and work-life balance and also to continue to attract people into the profession.

Abstract

Objectives To investigate factors affecting career satisfaction and work-life balance in specialist orthodontists in the UK/ROI.

Design and setting Prospective questionnaire-based study.

Subjects and methods The questionnaire was sent to specialist orthodontists who were members of the British Orthodontic Society.

Results Orthodontists reported high levels of career satisfaction (median score 90/100). Career satisfaction was significantly higher in those who exhibited: i) satisfaction with working hours; ii) satisfaction with the level of control over their working day; iii) ability to manage unexpected home events; and iv) confidence in how readily they managed patient expectations. The work-life balance score was lower than the career satisfaction score but the median score was 75/100. Work-life balance scores were significantly affected by the same four factors, but additionally were higher in those who worked part-time.

Conclusions Orthodontists in this study were highly satisfied with their career and the majority responded that they would choose orthodontics again. Work-life balance scores were lower than career satisfaction scores but still relatively high. It is important for the profession to consider ways of maintaining, or improving, career satisfaction and work-life balance; including maintaining flexibility of working hours and ensuring that all clinicians have ready access to appropriate training courses throughout their careers (for example, management of patient expectations).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Career satisfaction and work-life balance are important aspects of any profession. Career satisfaction may be defined as the overall happiness, feeling of accomplishment and success with one's occupational choices,1,2,3 whereas work-life balance commonly means successful and equal involvement in both work and life/family roles, with a minimum of conflict.4 High levels of career satisfaction and good work-life balance have been correlated with increased income, motivation, performance, psychological and physical well-being, self-confidence and commitment.4,5,6,7

Previous studies in the field of dentistry have investigated potential factors affecting career satisfaction. The relationship between different working patterns/working environments and how these affect career development, job satisfaction and quality of life have been studied in the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand.8,9,10,11 Studies have generally agreed that an area of special interest in dentistry, holding a postgraduate qualification and specialisation were associated with higher levels of career satisfaction and personal accomplishment.10,11,12,13,14

Orthodontics is often seen as a speciality which is low in stress and offers flexible working patterns. However, studies have also identified challenges including time management, occupational stress, patient demands, patient expectations/attitudes towards treatment, difficulties taking career breaks and working patterns.15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 The current knowledge of career satisfaction and work-life balance in orthodontics is limited and hence further research is important.

Aim of the study

This study therefore aimed to investigate the factors affecting career satisfaction and work-life balance in specialist orthodontists in the United Kingdom (UK) and Republic of Ireland (ROI).

Materials and methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the UCL Research Ethics Committee. This was a prospective questionnaire-based study and the questionnaire was developed based on themes identified in a previous qualitative study using one-to-one interviews to investigate factors affecting work-life balance in orthodontists in the United Kingdom.22

The questionnaire was assessed for validity, readability and ease of completion and was piloted several times with orthodontists working both in primary and secondary care before final distribution. After each pilot, amendments were made and the questionnaire went through a number of iterations until a final version was reached. The final questionnaire consisted of five sections: i) Demographic information; ii) Career choices; iii) Work-related information; iv) Overall fulfilment in their working life; and v) Assessment of career satisfaction and work-life balance. In the final section, respondents were asked to indicate their level of career satisfaction on a scale from 0 to 100, (where 0 was 'not satisfied at all' and 100 was 'very satisfied') and to rate their work-life balance on an identical scale (where 0 was 'the worst work-life balance imaginable' and 100 was 'the best work-life balance imaginable').

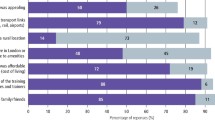

Table 1 illustrates the variables which could potentially affect career satisfaction or work-life balance and were included in the questionnaire. These variables were identified primarily from a previous qualitative study investigating this area22 but also from relevant dental and orthodontic publications. The majority of questions had either binary responses (for example yes/no or satisfied/not satisfied) or three potential options (for example management of unexpected home events could be classified as relatively easy, some difficulty or extremely difficult).

The questionnaire was distributed electronically via SurveyMonkey to specialist orthodontists in the UK/ROI who were members of the British Orthodontic Society (BOS) and currently working. Those working outside the UK/ROI, retired orthodontists, pre-CCST trainees and non-specialist members were excluded. The first email was sent in January 2016 and two subsequent reminders were sent at ten day intervals.

Statistical analysis was undertaken using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) and Stata (Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. StataCorp LP). Simple descriptive statistics were used to describe the demographics and work-related information and multiple regression analyses were used to investigate the potential impact of the various factors explored in the questionnaire on career satisfaction and work-life balance. All of the variables from Table 1 were entered into a series of univariable analyses to ascertain the effect on career satisfaction or work-life balance, this process determined the level of significance and aided in limiting the number of variables entered into the multivariable regression analysis. Any factors with P ≤0.1 were considered for inclusion in the multivariable analysis. Factors with P <0.05 in the multivariable analysis were then considered as having a significant effect on career satisfaction or work-life balance. The assumptions of the regression analyses were verified by a study of the residuals.

Results

The BOS sent 1,192 emails containing links to the SurveyMonkey questionnaire but there were a number of undelivered or rejected emails. Following three mailings, there were 321 usable responses and it was estimated that the response was approximately 32%.

Fifty-three percent of respondents were female and 47% were male. The mean age of respondents was 46.2 years (SD 9.3 years). Table 2 shows the geographical areas of main employment; almost 68% of respondents worked in an urban area, 27% in a semi-rural area and only 5% worked in a rural area. The majority of respondents were working full time (57%) and 59% were happy with their working hours.

The mean time since completion of orthodontic training was 15.2 years (SD 9.7), and the majority of respondents were working in either one or two places (31.8% and 36.8%, respectively). The main employment of the respondents was hospital consultant (38.3%), followed by practice owner/partner (27.1%) and non-partner/associate (20.9%). Much smaller numbers were university clinical academics or associate specialists/SDOs (less than 4%).

As described previously, all of the variables in Table 1 were included in the analyses, however only the significant findings will be discussed here.

Career satisfaction

The median career satisfaction score was 90 (Table 3). Multivariable regression analysis showed that four variables had a significant effect on the career satisfaction score, after accounting for all other variables in the model:

-

1

Satisfaction with working hours (P = 0.029): those who were satisfied with their working hours had scores which were, on average, 3.7 points higher than those who were not satisfied

-

2

Satisfaction with the level of control over the working day (P = 0.047): those who were satisfied with this element gave scores which were, on average, 4.4 points higher than those who were not

-

3

Management of unexpected home events/domestic issues (P = 0.043): those who found it relatively easy to manage these events scored, on average, 5.0 points more than those who found it to be extremely difficult

-

4

Management of patient expectations (P <0.001): those who felt they managed expectations well had higher career satisfaction scores by, on average, 8.9 points compared with those who found managing patient expectations increasingly difficult.

Work-life balance

The median work-life balance score was 75 (Table 4) and five of the variables entered into the multivariable regression had significant effects on work-life balance score, having accounted for all other variables in the model:

-

1

Working pattern (P = 0.052): this was of borderline significance but is included here due to the potential importance of this finding; those who worked part time had scores which were, on average, 4.3 points higher than those who worked full time

-

2

Satisfaction with working hours (P <0.001): those who were satisfied with their working hours had scores which were, on average, 12.7 points higher than those who were not

-

3

Satisfaction with the level of control over their working day (P = 0.032): those who were satisfied gave scores which were, on average, 5.6 points higher than those who were not

-

4

Management of unexpected home events/domestic issues: those who found it easy to manage these events scored, on average, 6.6 points higher compared with those who found it difficult (P = 0.013) and 12.0 points higher than those who found such situations extremely difficult to manage (P <0.001)

-

5

Management of patient expectations (P = 0.043). Those who felt they managed patient expectations well had work-life balance scores which were, on average, 5.5 points higher compared with those who found managing patient expectations increasingly difficult.

Respondents were also asked whether they would choose orthodontics again, or encourage a relative/friend to choose orthodontics as a career; 83% were certain that they would choose orthodontics again as a career, while 66% said that they would encourage a relative/friend to do so. A number of interesting free text comments were also made and some examples of these are included in Box 1.

Discussion

The overall response for this survey was 32% and the results must therefore be interpreted with some caution. There is clearly a risk that the respondents may not be representative, however, it did seem that responses were received both from people who were very happy with their career and others who were less happy. It should also be noted that this figure of 32% is very similar to the average response (34.6%) reported in a meta-analysis of online questionnaires by Cook et al.23

Whether the respondents were representative of the cohort the questionnaire was sent to must also be considered. The gender distribution of the respondents was 53% female and 47% male; this compares well with figures provided by the BOS for the cohort surveyed (50% female; 50% male). Of those who responded, 38.3% gave hospital consultant as their main employment. This is slightly higher than the percentage for the cohort surveyed and figures indicate that approximately 30% of those who received the questionnaire were consultant orthodontist group members. This difference should be considered when interpreting the findings.

The strength of this study was that the questionnaire was developed based on the findings of a qualitative study where in-depth interviews were undertaken with orthodontists to ascertain the key factors affecting career satisfaction and work-life balance and therefore these factors were based on the opinions of the profession and not just the research team.22

The majority of orthodontists stated that they would choose orthodontics again as a career (83%); this was in agreement with the findings of Roth et al.15 who found that 80% of Canadian orthodontists were satisfied with their choice of profession. In the current study, 66% said they would encourage a relative/friend to pursue orthodontics as a career compared with a higher figure of 84% in the Roth et al.15 study. Free text comments for this question suggested that this was affected by the challenges and difficulties encountered throughout the training pathway and the current levels of uncertainty within the NHS (for example, contracting issues in practice).

Orthodontists in the current study reported a high level of career satisfaction (median score 90; range 0–100). Four factors significantly affected career satisfaction: satisfaction with working hours; satisfaction with the level of control over the working day; ease of managing unexpected home events/domestic issues; and ease of managing patient expectations, with the largest effect on score related to managing patient expectations.

In comparison with other studies, the high level of job satisfaction in Canadian orthodontists was explained by respect, relationships with patients, staff and colleagues, income, and delivery of care. However, dissatisfaction was mainly related to insufficient personal time, practice management and threat of litigation.15

The median work-life balance score was 75 points (range 0–100). This median score was high, but lower than the career satisfaction score. This was consistent with the findings of Bateman et al.22 where respondents felt that the aspects of their job which gave them the most career satisfaction were sometimes the aspects which affected their work-life balance the most (for example, being involved in teaching/training in the hospital sector). The multivariable analysis for work-life balance showed that the scores were significantly affected by the same four variables as for career satisfaction and, additionally, working patterns (whether people were working full-time or part time) also showed borderline significance.

There is no actual 'cut-off' for those variables which would be considered clinically important but those variables with larger coefficients/effect sizes are more likely to have an impact on somebody's career satisfaction or work-life balance. The only way of knowing if something is truly clinically important is to consider the implications from a professional standpoint as made by experienced clinicians; this would be an interesting area to consider in future research.

A number of previous studies in the UK and New Zealand found that an area of special interest and holding a postgraduate degree or specialisation were associated with high levels of professional and career satisfaction, positive work experience, higher levels of personal accomplishment and work engagement, lower stress levels and reduced levels of emotional exhaustion.10,11,12,13 This was mainly explained by involvement in teaching, research and administrative duties and the variety in the working day. The current study adds support to these findings, with specialist orthodontists reporting high levels of career satisfaction.

Working patterns of respondents did not have a significant effect on career satisfaction, however, work-life balance scores were 4.3 points higher for those respondents working part time compared with those working full time and this was of borderline significance (P = 0.052). Other studies have reported that the number of hours worked per week was significantly related to the overall level of occupational stress and was considered a factor affecting work-life balance.16,21 A career in orthodontics is often seen as offering flexibility for those with families and female orthodontists have previously been reported as being more satisfied with their work-life balance.19,20,21

Career satisfaction and work-life balance scores were significantly affected by satisfaction with working hours. Respondents who were dissatisfied with their working hours had lower career satisfaction and lower work-life balance scores compared with those who were satisfied with their working hours (3.7 points and 12.7 points, respectively) and the majority of dissatisfied respondents indicated that they would reduce their hours worked if feasible. In medicine, studies have also shown that increased working hours are associated with higher levels of career dissatisfaction.24,25,26

The majority of respondents (72%) were satisfied with the level of the control over their working day but those respondents who were dissatisfied with this element of their work had reduced career satisfaction and work-life balance scores compared with the satisfied respondents (lower by 4.4 points and 5.6 points, respectively). More control may be associated with a greater sense of personal accomplishment and it might be that orthodontists have personalities where they like to 'be in control' and career satisfaction may therefore also be related to certain personality traits, such as perfectionism, and having a calm nature.21

Managing unexpected home events and domestic issues was also considered; 45.8% of the respondents said they found this quite difficult and 33% said it was extremely difficult. This resulted in lower career satisfaction scores by five points for those who found managing such events extremely difficult compared with those who found this easy (P = 0.043). Work-life balance scores were also significantly affected and respondents who managed unexpected home events with some difficulty or felt that it was extremely difficult had significantly lower work-life balance scores (by 6.6 points and 12 points, respectively) compared with those who found it relatively easy. This could be attributed to reduced flexibility in working patterns, especially in an orthodontic setting where appointments are routinely booked a number of weeks ahead. Current working patterns also mean that it is likely that both partners may be working, further causing an increase in the conflict between balancing work and family life.27

Managing patients' expectations continues to be a challenge for dentists and orthodontists,15,16,20,21,22 and this had a significant impact on both career satisfaction and work-life balance. The majority of respondents (86%) said they felt they managed patient expectations well, however those who said they found managing patient expectations increasingly difficult had significantly reduced career satisfaction scores (by 8.9 points), and reduced work-life balance scores (by 5.5 points) compared with those who felt they managed patient expectations well. Increasing demands for appointments outside normal working hours and managing unrealistic patient expectations were issues discussed by interviewees in previous studies in the UK, New Zealand and Canada.15,16,20,21,22 This highlights the importance of training dentists and orthodontists in managing patient expectations at undergraduate and postgraduate level and throughout an individual's career in order to reduce the impact of these issues on career satisfaction and work-life balance.

The impact of these findings for the profession must be considered in order to maintain, or preferably improve, career satisfaction and work-life balance and also to continue to attract people into the profession. These include ensuring continued flexibility of working hours in order to allow part-time working where people wish to do so and also to allow clinicians to manage unexpected home events without placing them under high levels of stress. Additionally, managing patient expectations was a factor which influenced career satisfaction and work-life balance. This highlights the importance of providing patient management training in both undergraduate and postgraduate curricula and through continuing professional development courses. Mentoring may also play a role in helping clinicians to manage stressors in their day-to-day practice.

Conclusions

Orthodontists were highly satisfied with their career and also reported relatively good levels of work-life balance.

Factors significantly affecting career satisfaction were satisfaction with working hours, satisfaction with the level of control over the working day, ability to manage unexpected home events and confidence in how readily the respondents managed patient expectations. Work-life balance scores were significantly affected by the same four factors, but additionally by working patterns.

The decision to pursue a career in orthodontics was looked upon positively by the majority of respondents, but the challenges and difficulties associated with the long training pathway, along with the obstacles, sacrifices and burdens were highlighted.

References

Zingeser L . Career satisfaction and job satisfaction: What ASHA surveys show. The ASHA Leader 2004; 9: 4–5.

Kaliski B S . Encyclopaedia of Business and Finance, Second edition. p 446. Detroit: Thompson Gale, 2007.

Robbins S P, Judge T A . Organizational behaviour, Fifteenth edition. Essex, England: Pearson, 2011.

Clark S C . Work/family border theory: A new theory of work/family balance. Human Relations 2000; 53: 747–770.

Korman A K, Mahler S R, Omran K A . Work ethics and satisfaction, alienation, and other reactions. In W B. Walsh and S H. Osipow (Eds.) Handbook of vocational psychology. Vol. 2. pp 181–206. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1983.

Friedman S D, Christensen P, DeGroot J . Work and life: The end of the zero-sum game. Harvard Business Review 1998; 76: 119–130.

Mullins J L . Management and organizational behaviour, Ninth edition. Pearson Education Limited: Essex, 317, 2010.

Newton J T, Thorogood N, Gibbons D E . The work patterns of male and female dental practitioners in the United Kingdom. Int Dent J 50: 61–68, 2000.

Luzzi L, Spencer A J, Jones K, Teusner D . Job satisfaction of registered dental practitioners. Aust Dent J 2005; 50: 179–185.

Ayers K M, Thomson W M, Newton J T, Rich A M . Job stressors of New Zealand dentists and their coping strategies. Occup Med 2008; 58: 275–281.

Ayers K M, Thomson W M, Rich A M, Newton J T . Gender differences in dentists' working practices and job satisfaction. J Dent 2008; 36: 343–350.

Gilmour J, Stewardson D A, Shugars D A, Burke F J T . An assessment of career satisfaction among a group of general dental practitioners in Staffordshire. Br Dent J 2005; 198: 701–704.

Denton D A, Newton J T, Bower E J . Occupational burnout and work engagement: a national survey of dentists in the United Kingdom. Br Dent J 2008; 205: E13.

Oweis Y, Hattar S, Eid R A, Sabra A . Dentistry a second time? Eur J Dent Educ 2012; 16: e10–e18.

Roth S F, Heo G, Varnhagen C, Glover K E, Major P W . Job satisfaction among Canadian orthodontists. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 2003; 123: 695–700.

Roth S F, Heo G, Varnhagen C, Glover K E, Major P W . Occupational stress among Canadian orthodontists. Angle Orthod 2003; 73: 43–50.

Collins J M, Cunningham S J, Moles D R, Galloway J, Hunt N P . Factors which influence working patterns of orthodontists in the United Kingdom. Br Dent J 2009; 207: E1.

Collins J M, Hunt N P, Moles D R, Galloway J, Cunningham S J . Changes in the gender and ethnic balance of the United Kingdom orthodontic workforce. Br Dent J 2008; 205: E12.

Davidson S, Major P W, Flores-Mir C, Amin M, Keenan L . Women in orthodontics and work-family balance: challenges and strategies. J Can Dent Assoc 2012; 78: c61.

Soma K J, Thomson W M, Morgaine K C, Harding W J . A qualitative investigation of specialist orthodontists in New Zealand: Part I. Orthodontists and orthodontic practice. Aust Orthod J 2012; 28: 2–16.

Soma K J, Thomson W M, Morgaine K C, Harding W J . A qualitative investigation of specialist orthodontists in New Zealand: part 2. Orthodontists' working lives and work-life balance. Aust Orthod J 2012; 28: 170–180.

Bateman L E, Collins J M, Cunningham S J . A qualitative study of work-life balance among specialist orthodontists in the United Kingdom. J Orthod 2016; 43: 288–299.

Cook C, Heath F, Thompson R L . A meta-analysis of response rates in web-or internet-based surveys. Educ Psychol Measurement 2000; 60: 821–836.

Leigh J P, Kravitz R L, Schembri M, Samuels S J, Mobley S . Physician career satisfaction across specialties. Arch Int Med 2002; 162: 1577–1584.

Leigh J P, Tancredi D J, Kravitz R L . Physician career satisfaction within specialties. BMC Health Serv Res 2009; 9: 166.

Van Ham I, Verhoeven A A, Groenier K H, Groothoff J W, De Haan J . Job satisfaction among general practitioners: a systematic literature review. Euro J Gen Pract 2006; 12: 174–180.

Scott J, Clery E . Gender roles: an incomplete revolution. British social attitudes: the 30th report. pp 115–128. London: NatCen Social Research, 2013.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all of the orthodontists who took the time to complete the questionnaire and without whom this study would not have been possible. We would also like to thank Dr Dirk Bister and Professor Tim Newton for their advice when developing the questionnaire and Ann Wright (BOS) for distribution of the questionnaire and for her assistance in dealing with our questions.

If any readers wish to have a copy of the questionnaire, please contact the authors directly.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Junaid, S., Hodges, S., Petrie, A. et al. Career satisfaction and work-life balance of specialist orthodontists within the UK/ROI. Br Dent J 223, 53–58 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.585

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.585

This article is cited by

-

Key determinants of health and wellbeing of dentists within the UK: a rapid review of over two decades of research

British Dental Journal (2019)