Key Points

-

Describes a model of decision-making style which is relevant to clinical decision-making.

-

Shows that common, anxiety-provoking clinical stressors affect dentists' clinical decision-making.

-

Finds that dentists appear to have a more effective style of decision-making than the general public.

-

Shows how, despite this, decision-making style is associated with burnout.

Abstract

Aims To develop a measure of dentists' anxiety in clinical situations; to establish if dentists' anxiety in clinical situations affected their self-reported clinical decision-making; to establish if occupational stress, as demonstrated by burnout, is associated with anxiety in clinical situations and clinical decision-making; and to explore the relationship between decision-making style and the clinical decisions which are influenced by anxiety.

Design Cross-sectional study.

Setting Primary Dental Care.

Subjects and methods A questionnaire battery [Maslach Burnout Inventory, measuring burnout; Melbourne Decision Making Questionnaire, measuring decision-making style; Dealing with Uncertainty Questionnaire (DUQ), measuring coping with diagnostic uncertainty; and a newly designed Dentists' Anxieties in Clinical Situations Scale, measuring dentists' anxiety (DACSS-R) and change of treatment (DACSS-C)] was distributed to dentists practicing in Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire. Demographic data were collected and dentists gave examples of anxiety-provoking situations and their responses to them.

Main outcome measure Respondents' self-reported anxiety in various clinical situations on a 11-point Likert Scale (DACSS-R) and self-reported changes in clinical procedures (Yes/No; DACSS-C). The DACSS was validated using multiple t-tests and a principal component analysis. Differences in DACSS-R ratings and burnout, decision-making and dealing with uncertainty were explored using Pearson correlations and multiple regression analysis. Qualitative data was subject to a thematic analysis.

Results The DACSS-R revealed a four-factor structure and had high internal reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.94). Those with higher DACSS-R scores of anxiety were more likely to report changes in clinical procedures (DACSS-C scores). DACSS-R scores were associated with decision-making self-esteem and style as measured by the MDMQ and all burnout subscales, though not with scores on the DUQ scale.

Conclusion Dentists' anxiety in clinical situations does affect the way that dentists work clinically, as assessed using the newly designed and validated DACSS. This anxiety is associated with measures of burnout and decision-making style with implications for training packages for dentists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There have been many studies exploring the levels of stress in dentists.1,2,3,4 By definition,5 a state of being stressed occurs when one encounters a threatening event which is perceived as being beyond one's ability to cope effectively. In the dental context, stress has been implicitly associated with anxiety and worry-type emotions. However, Chapman and colleagues6,7,8 reported that stress may be accompanied by a variety of negative emotions such as frustration and guilt.

Investigations1,3,9 into the emotional experiences/stress of dentists have previously focused on the significant levels of burnout (a response to the chronic emotional strain of dealing with people, particularly if they have problems10) which they experience. In 2007, te Brake11 reported that levels of burnout increased from 1997–2001, and Denton et al.1 reported that 8% of sample of dentists surveyed in the UK had burnout. There are multiple factors associated with the development of burnout including workload, control, monetary reward, social stressors (including from patients) and personal values.12

There are three aspects to burnout;13 emotional exhaustion (EE; feelings of being emotionally overwhelmed and exhausted by work), depersonalisation (DP; a cynical, detached feeling towards patients/clients), and a reduced sense of personal achievement (PA; one's sense of professional competence and success). There is some evidence from longitudinal studies14,15,16 that EE occurs first, followed by increasing levels of DP and finally a reduced sense of PA. There is some evidence for a vicious circle where EE predicts DP and also DP predicts EE and PA over time.16

Burnout appears to be related to deficits in executive functioning or cognitive control17 (working memory, reasoning, problem solving, planning and execution). Clinician burnout can affect the quality and safety of patient care including rates of medical errors,18,19 presumably mediated by effects on executive function. There appears to be a dose-response relationship between the factors.20 However, self-reported medical errors are associated with a subsequent worsening of all domains of burnout, suggesting that a vicious circle may be in action.19 The cognitive deficits associated with burnout appear to persist beyond apparent clinical recovery and return to work.21 This has profound implications for patient safety.

There is very limited experimental evidence22 of the effects of stress on intra-operative care. What there is suggests that stress affects performance in surgeons (in particular during highly stressful laparoscopic procedures), that experienced surgeons experience less stress and are consequently less impaired, and that stress impairs surgeons' nontechnical skills such as decision-making and communication skills.

There appear to be no studies, of which the authors are aware, of any potential association of stress, anxiety or burnout and either self-reported or experimental effects on clinical decision-making or clinical errors in dentists. However, a link has been established between working demands within the surgery and clinical accidents, such as dropping instruments.23

Janis and Mann24 developed a generic analysis of various styles of decision-making which individuals were prone to use under varying degrees of stress such as increased time pressure. Decisional or cognitive conflict (the simultaneous opposing tendency to accept and reject a particular course of action) results in hesitation, vacillation, feelings of uncertainty and emotional stress which become acute when the decision-maker is aware of the potential losses of a particular course of action.

Janis and Mann24 proposed that there was no such thing as a bad decision, just a bad decision-making process. Decisions are often motivated by the need to protect oneself from anxiety and to nurture one's decisional self-esteem (competence and reputation as a decision-maker). Threats to decisional self-esteem cause both psychological stress and attempts to avoid post-decisional regret and anticipated guilt or shame about the decisions made. They define four types of decision-making as described in Table 1.

There are more recent models of decision avoidance (see Anderson25 for review); however, the vigilant, hypervigilant, buck-passing and procrastination aspects of the Janis and Mann model are assessable using an internationally validated questionnaire; the Melbourne Decision-Making Questionnaire (MDMQ).26,27

Decisional conflict has been found to impact on health-related decisions in patients,24,28 physicians' clinical decisions,29 and to form a vicious circle of personal uncertainty in physician-patient interactions.30 In an exploration of the effect of burnout on child protection decisions by child protection officers, McGee31 found that burned out workers made more rapid decisions, typically based on one piece of information; that neglected children were not at risk. Their decisions were held with greater conviction and unwavering certainty. The authors interpreted this in the light of Janis and Mann's defence avoidance; burned out workers were avoiding involvement in the situation.

Errors in clinical decision-making in the fields of medicine and surgery have been widely discussed, particularly in relation to diagnostic errors. Croskerry32 has developed a model of the aetiology of diagnostic errors and this allows for the impact of 'affective states' (such as anxiety disorders) and mood disorders (such as depression on diagnosis). This model appears to have been the subject of very limited empirical evaluation. Poor decision-making processes have been found to lead to poor outcomes.33

Schneider et al.34 have developed a questionnaire (The Dealing with Uncertainty Questionnaire; DUQ) to evaluate how general medical practitioners deal with uncertainty in clinical practice. This has two subscales: (1) Diagnostic Action, which evaluates actions taken to clarify diagnostic decision-making, eg referral to a specialist or ordering more tests; and (2) Diagnostic Reasoning, which measures the use of intuition, delaying diagnosis and the influence of the patient's social background on diagnosis. Scores on the Diagnostic Action Scale were positively correlated with a measure of anxiety due to uncertainty in clinical situations.

This study aimed to:

-

1

To develop a measure of dentists' anxiety in clinical situations

-

2

To establish if dentists' anxiety in clinical situations affected their self-reported clinical decision-making

-

3

To establish if occupational stress, as demonstrated by burnout, is associated with anxiety in clinical situations and clinical decision-making; and

-

4

To explore the relationship between decision-making style and the clinical decisions which are influenced by anxiety.

The hypotheses were that:

-

1

Dentists' anxieties in clinical situations would affect their self-reported clinical decision-making

-

2

Occupational stress, as demonstrated by burnout, would be related to anxiety in clinical situations and changes in clinical decision-making, and

-

3

Dentists' decision-making style (in particular avoidant and hypervigilant decision-making) would be associated with and the clinical decisions which are influenced by anxiety.

Method

Questionnaires

Demographics

This was based on an existing questionnaire35 with minor modifications, for example to allow identification for dentists working in the salaried services.

The Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HS)13

This is the most commonly used measurement of burnout, which has been widely used with dentists.1,3 It has three subscales measuring:

-

1

Emotional exhaustion (EE); 9 items (I feel used up at the end of the workday.)

-

2

Depersonalisation (DP); 5 items (I've become more callous toward people since I took this job.)

-

3

Personal achievement (PA); 8 items reverse scored (I can easily create a relaxed atmosphere with my recipients.)

Items are scored on a 6-point Likert scale rating how often the feelings are experienced and anchored 'never; 0' to 'every day; 6.'

Melbourne Decision-Making Questionnaire (MDMQ)26,27

This is a well-validated questionnaire which assesses decision-making style as described by Janis and Mann. It has two parts. Part one (6 items) assesses decision-making self-esteem (eg, I feel confident about my ability to make decisions); Part 2 assesses styles of decision-making. There are four subscales measuring: vigilance, (6 items; I try to be clear about my objectives before choosing); hypervigilance, (5 items; Whenever I face a difficult decision I feel pessimistic about finding a good solution); procrastination, (5 items; Even after I have made a decision I delay acting upon it); and buck-passing (6 items; I do not like to take responsibility for making decisions). All items are scored on a 3-point scale (0–2), labelled 'true', 'sometimes true', 'not true... for me'.

Dealing with Uncertainty Questionnaire (DUQ)34

This was developed to measure the impact of uncertainty on the decision-making process of general medical practitioners. The original German text was obtained and translated into German by a native speaker and the text slightly modified to make it applicable to primary care dentists. It consists of two subscales:

-

1

A six-item diagnostic action scale (eg, I frequently refer patients to other doctors/dentists when I am uncertain of a diagnosis)

-

2

A six item diagnostic reasoning scale (eg, Intuition plays a role for me in making diagnostic decisions).

It is scored on a 6-point Likert scale anchored 'strongly agree' and 'strongly disagree.'

Dentists Anxieties in Clinical Situation Scale (DACSS)

A pool of 30 items was generated based on the stressors revealed by previous research.4,6,7,36 The subjective importance of the stressors to dentists, as revealed by a previous study,7 influenced the final choice of 20 items for inclusion, which was made by the three researchers in committee. For each of the 20 items, dentists were asked to rate their anxiety on an 11-point Likert scale anchored 0 (not at all) and 10 (the most intense emotion you can experience). For each item they were asked, 'Does the anxiety ever change something about the way you work?' and were asked to indicate yes or no (Y/N). This resulted in 2 subscales; the DACSS-R which rated anxiety and the DACSS-C which reported change in decision-making.

The questionnaire also asked dentists, 'If you have said that anxiety affects your decision-making in some circumstances, can you please describe up to 2 situations or the types of situations when this happened? Please describe the situation and the effect on your decision-making.'

Procedure

Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology, the University of Lincoln.

The research method was piloted with nine volunteer primary care dentists. These dentists were recruited from the volunteer pool of a previous study.7 They were sent, by post, a covering letter explaining the nature of the research, a consent form, a questionnaire pack and a prepaid return envelope. Once the forms were returned, HC contacted the dentists by telephone and asked for feedback on the research pack. Participants suggested moving the DACSS items on ethical conflict to the end of the questionnaire with instructions not to complete those items if the participants were salaried.

A total of 792 dentists whose names appeared on the General Dental Council register for postcodes in the Nottingham, Nottinghamshire, Hull, Lincoln, Lincolnshire and North Lincolnshire areas were contacted by post. This gave a cross-section of dentists working in inner city, suburban and rural areas. Dentists whose addresses specified orthodontic practices and maxillo-facial departments were excluded. Participants were offered a chance to win one of five £20 M&S vouchers. Six weeks after the first send, a second send was posted to 667 dentists. The returns (Table 2) resulted in a final sample of 187 dentists; an overall return rate of 34.1% and a usable form rate of 23.6%.

Numerical data was entered into SPSS (IBM Statistics, Version 22.0, Armonk, NY). Qualitative data elicited in response to the request for examples was manually transferred, verbatim, to a Microsoft Office 2010 Excel spreadsheet. One researcher (HC) immersed herself in the data by reading and re-reading the entries. It became apparent that they could be analysed using the same thematic framework established in a previous study.7 A sample analysis was reviewed by RB.

Results

One hundred and eighty-seven dentists returned completed questionnaires. Dentists from a range of practice types, working hours and number-of-years qualified took part (Table 3). Missing values from the DACSS-R (Rating of anxiety subscale), DUQ, MBI and MDMQ were replaced with that participants mean for that questionnaire, with the exception of R18, R19, R20 from the DACSS-R. The missing values were not replaced for these three items because it is likely that respondents deliberately did not complete these items as they felt they did not apply to them, and there was a large number of participants who did not complete these items. There were missing values across these items for 38 of the 187 respondents; 30 respondents did not complete R18, R19 and R20, 7 respondents did not complete R20 and 1 did not complete R18 and R20. Across all the other scales there was no pattern to the missing values, with the exception of the 'change in clinical behaviour subscale' of the DACSS (DACSS-C); for which missing values were not replaced as answers were categorical No (0) or Yes (1) and it was not clear if missing responses indicated 0 or failure to answer. There was a greater amount of missing data towards the end of this subscale.

What levels of anxiety do dentists experience in primary care dental practice?

Dentists in primary care dental practice reported experiencing high levels of anxiety from a number of regularly occurring clinical situations. Multiple t-tests revealed that the highest levels of anxiety were reported by those dentists who indicated that the anxiety causes them to change something about the way they work. Across all situations, those dentists who reported that their anxiety caused them to change the way they work reported experiencing more intense levels of anxiety than dentists who reported that anxiety did not change the way they work (Table 4).

What underlying components can explain the variance in levels of anxiety reported by dentists?

To identify underlying components which might explain the variance in levels of anxiety reported by dentists, a principal component analysis (PCA) with orthogonal rotation was conducted with data from 149 participants on the 20 items from the DACSS-R. Data from 38 participants was excluded as they had not completed items R18-R20. (NB An analysis on items 1-17 with 187 participants identified the same pattern of components, the only consequential difference being that item 12 loaded onto component 3 in that analysis, rather than component 2.) One item (Item R3) was identified as having low correlations (<0.3) with 45% of DACSS-R items and was therefore removed from further analysis. To eradicate multicollinearity two items with high correlations (>0.6) with 25% of DACSS-R items were removed from further analysis (items: R2, R4). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure verified the sampling adequacy for the analysis, KMO = 0.93 ('superb' according to Field, 200937), and all KMO values for individual items were >0.89, which is well above the acceptable limit of 0.5 (Field, 2009). Bartlett's test of sphericity (χ2 (136) = 1484.31, p <0.001), indicated that correlations between items were sufficiently large for a PCA. An initial analysis was run to obtain eigenvalues for each component in the data. Three components had eigenvalues over Kaiser's criterion of 1 and in combination explained 63.70% of the variance. However, examination of the communalities after extraction revealed that for 12 of the 17 items the value was <0.7, suggesting that Kaiser's rule may not be accurate. According to Jolliffe's criterion (retain components with eigenvalues greater than 0.7), four components should be retained. Examination of the scree plot showed inflexions that would justify retaining three or four components. Therefore, the analysis was rerun specifying the extraction of four components. With four components retained, 69.40% of the variance was explained, therefore the 4-component model was chosen. Items were selected for inclusion in a component where the factor loading was greater than 0.4, where items loaded onto more than one item at greater than 0.4 the greatest component loading was selected. To consider the fit of the model for the data, the reproduced correlation coefficients were examined and compared to the original correlation coefficients. These showed 27% of the residuals had absolute values greater than 0.05 indicating a good fit of the model. The rotated component matrix shows the component loadings after orthogonal rotation (Table 5). This suggests that component 1 represents uncertainties in clinical practice, component 2 represents threats to sense of control, component 3 represents challenging patients and component 4 represents ethical dilemmas. The DACSS-R had high reliability, Cronbach's α = 0.94. (See Table 5 for α values for subscales.)

The levels of reported anxiety from the different components were compared using repeated measures one-way ANOVA which revealed a significant main effect (F(2.65,392.41) = 54.18, p <0.001, partial eta squared = 0.27). Post-hoc t-tests revealed that dentists reported no significant difference between anxiety levels between component 1 and 2, and significantly less anxiety between all other pairwise comparisons (p <0.001). This reflected equally high anxiety for components 1 and 2, and reduced anxiety for component 3, with lowest levels of anxiety for component 4 (Table 6).

Are decision-making style and burnout associated with dentists' anxieties in clinical situations?

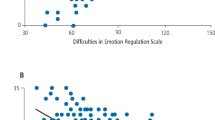

The relationship between decision-making style and anxiety was examined by performing a series of Pearson correlations on the average level of anxiety from the DACSS-R and the various subscales of the MDMQ, MBI and DUQ (Table 7). This showed that as decision self-esteem increases and personal accomplishment increases, the level of anxiety decreases, whereas buck-passing, procrastination, hypervigilance, emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation decrease as levels of anxiety decrease. Further investigation of the relationships between decision-making anxiety style and anxiety was carried out through regression analyses.

Can decision-making characteristics of primary care dentists be used to predict anxiety levels?

The average score of anxiety ratings on the post PCA DACSS-R (Table 8) was used as a dependent variable in a multiple regression; predictor variables were components of the Melbourne Decision-Making Questionnaire, Maslach Burnout Inventory and Dealing with Uncertainty Questionnaire. (Table 9) An initial enter method multiple regression revealed that hypervigilance (from the MDMQ), emotional exhaustion (from the MBI) and decision self-esteem (from the MDMQ) were significant predictors of anxiety. Therefore, a forward stepwise multiple regression was conducted to identify the explanatory contribution of each of these significant predictors. Thirty-one percent of the variance in anxiety was explained by hypervigilance, with an additional 9% explained by emotional exhaustion and an additional 2% by decision self-esteem.

Responses to request for examples

In response to the open-ended request for up to two examples of situations where anxiety affected their clinical decision-making, 124 participants provided a total of 172 examples, some of which contained examples of more than one stressor or coping strategy. The thematic system used7 consisted of 36 codes organised into 6 themes; 'emotions expressed by dentists', 'negative situations described by dentists', 'positive/challenging situations described by dentists', 'effects internal to the dentist', 'resultant coping strategies', 'not pertinent'. A summary of the described situations (stressors) appears in Table 10. Some of the examples were obviously prompted by questions on the DACSS, as the question text was referred to in the example, eg 'Q13 [You receive a solicitor's letter alleging negligence]' [Case 25].

The effects of anxiety on the dentists' self-reported decision-making (the coping strategies used) are described in Table 11. Again, these overlapped with the coping strategies described in an earlier study.8 Some dentists reported that stress was the sole outcome of the event, eg 'Stress, tension' [Case 586].

Thus it may be seen that these results confirmed the analysis of dentists' stressors and coping responses which were established in previous studies,6,7,8 indicating that the previous results were generalisable to a wider population and provide evidence of validity.

Discussion

This study reports the development of the Dentists' Anxiety in Clinical Situations Scale (DACSS); the first scale of which the authors are aware, to attempt to quantify the impact of self-reported clinical anxieties (DACSS-R) on clinical working (DACSS-C). This scale shows a high degree of reliability and therefore promise for future use in studies of dentists' anxiety and stress. Gorter et al.38 established that there were 49 separate stressors experienced by dentists and Humphris & Cooper identified still more.39 The items included in the DACSS-R were not simply designed to measure stress-evoking situations, but more specifically, anxiety-provoking situations which had been described as important in prompting changes in clinical decision-making by the participants of the previous studies.6,7,8 The constructs underlying the DACSS-R were found to explain nearly 70% of the variance in anxiety suggesting that this is a very useful measure in explaining the particular elements of anxiety which lead to overall feelings of anxiety in dentists.

The regression analysis revealed that the types of situations causing anxiety were summarised under components of: uncertainties in clinical practice, threats to sense of control, challenging patients, and ethical dilemmas. The highest levels of anxiety were reported to occur in response to uncertainties in clinical practice and threats to sense of control. These scales make intuitive sense within the clinical environment.

A close relationship was found between anxiety (DACSS-R), decision-making style and burnout. Decreased anxiety was associated with higher decisional self-esteem and sense of personal accomplishment; if one is confident in one's belief in one's decision-making effectiveness, one is likely to suffer less anxiety about the decisions taken and gain a greater sense of achievement from work. Increased anxiety (DACSS-R) was associated with the avoidant decision-making styles of buck-passing, procrastination, hypervigilance as predicted by the Janis and Mann model.24 DACSS-R scores were associated with the burnout characteristics of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation. Given that burnout is related to deficits in executive functioning (working memory, problem solving, reasoning, planning and execution17), it is not surprising that burnout scores were related to avoidant and hypervigilant decision-making styles, which are also associated with poor cognitive functioning.40 If DACSS-R is viewed as a proxy for state anxiety, this finding confirms previous research in other professional environments,41,42 that state anxiety is linked to burnout, though others have not found this link.43 Further research into the links between state anxiety, the DACSS and burnout is needed. If one is suffering from EE and DP it is easy to understand how being cut off from and cynical about one's patients could impact on one's anxiety about decisions taken and that anxiety about decisions taken could lead to increased levels of EE and DP, thus forming a vicious circle.

Qualitative examples of the effects on decision-making included modifying the treatment plan, referring on, effects on the treatment given, changes to procedures and interpersonal interactions, and effects on the style of decision-making thus confirming previous findings.8 It is important to note that this may well be different from the anxiety associated with clinical tasks such as the careful removal of caries in a very deep cavity where the risk of pulpal exposure is high; a situation which should usually provoke vigilant decision-making. This distinction needs to be clarified by further research.

Despite the links demonstrated between DACSS-R and decision-making, it is reassuring to note that, compared to the general population,27 the population means for the study were greater for decisional self-esteem and vigilance and lower for avoidant decision-making. This suggests that the clinical training dentists receive44 in making diagnostic and clinical decisions is effective and protects patients to a certain extent from the potential impact of dentists' anxieties when working.

The important impact of potential interpersonal disagreements with patients is reflected in the correlation of DACSS-R R4 (Something goes wrong on a patient who is 'difficult') with 25% of the other items and its consequent removal from the analysis. This might be interpreted as reflecting another layer of ubiquitous stress in addition to the stress of, say, 'A patient doesn't like the appearance of the crowns/bridgework you are about to fit, which are really very good' (R6) or 'Running late' (R7). Indeed, Schaufeli et al.45 found that, in primary care physicians, about 75% of burnout was stable over time and the remaining 25% was associated with the number of demanding patient visits to which physicians were exposed. Moreover, GPs who attempted to cope with their emotional exhaustion by distancing themselves emotionally from their patients, evoked demanding and threatening behaviour15 in what appears to function as a vicious circle. The rise of the 'consumerist' health service is particularly relevant to dentistry where most treatment is (at least partly) paid for46 and is likely to fuel this destructive cycle. Similarly, in experimental conditions, being under time pressure has been shown to be associated with a deterioration in executive functioning associated with decision-making.40 The same 'universality' argument might be made for 'You have to undertake a particularly difficult clinical procedure' (R2).

The weaker multicollinearity of question R3 ('A patient complains about the difficulty of getting appointments') may reflect the fact that, although it would compound many difficult situations, dentists are often buffered from this by reception and nursing staff.

On first consideration, 'You receive a solicitor's letter alleging negligence' (R 13) may appear to be out of place in the scale 'Uncertainties in clinical practice.' However, dentists report here (Table 1; Case 181) and elsewhere8 that receipt of such a letter makes them question their clinical practice and procedures. This suggests episodes of more chronic hypervigilance, usually as a result of complaints and litigation.

'I received a solicitor's letter following problems after an extraction on a new patient to the practice, who[m] I was aware had been unhappy with their previous GDP. It has made me cautious and more anxious at treating new patients, particularly those unhappy with their previous GDP and made me try to avoid treatment unless needed. Also reduced confidence in extractions and made me more likely to refer/ask for help at an early stage.' [Case: 729]

This level of chronic arousal is also provoked by being obliged to continue to treat patients who have complained.6,7 The hypervigilance provoked may be more akin to the hypervigilance for threat described in the clinical literature as associated with anxiety disorders and is accompanied by a selective attention to threat.47 It has been argued that these phenomena precipitate or maintain a feedforward loop which increases anxiety.48 This suggests that a speedy resolution to complaints, no matter where they are handled, is paramount.

The association of DACSS-R score with burnout suggests that burnout is associated with greater anxiety about clinical decisions. The positive association with the buck-passing, procrastination and hypervigilance subscales, and the negative association with the vigilant subscale of the MDMQ, suggests that dentists' anxiety is linked to poor (avoidant) decision-making. The weaker relationship with the DUQ diagnostic action scale suggests that dentists may not be fully aware of the impact anxiety is having on their reasoning processes. A previous study8 found that dentists would often deny that their emotions, including anxiety, affected their decision-making and then proceeded to describe how it actually changed their clinical approach. The weaker relationship of the DUQ may also reflect a lack of generalisability of the questionnaire from general medical practice. Further research would benefit from the development of a specific measure.

The positive correlation of EE and DP and the negative correlation with the level of, protective, personal achievement, with anxiety in clinical situations suggests that another vicious circle may be operating. Once a practitioner starts to burnout, they may become more anxious in clinical situations, they are then more likely to make avoidant decisions and this may feed forward to fuel anxiety. The results support the findings of McGee31 that burned out social workers took avoidant decisions.

The possible lack of awareness by dentists of the impact of anxiety on their decisions reinforces the impression given in a previous study7 in which dentists reported that anxiety did not change their decision-making but then went on to describe exactly how it did so. This leads to the possibility that making dentists more aware of decisional processes would facilitate reflection and improve dentists' decision-making and thus patient outcomes.

Threats to decisional self-esteem are a source of stress.24 This study showed that a robust decisional self-esteem was negatively associated with levels of clinical anxieties. It is possible to hypothesise that the ubiquitous stressor of the difficult patient, who is demanding and challenges one's clinical decisions, threatens the dentists' sense of decisional self-esteem.

Chambers has previously suggested that dentists have a 'core need for control' which is threatened by 'uncooperative patients, incompetent staff and government and insurance intrusions'.49 This theme was identified in previous research6,7 and is further validated by the emergence of the factor labelled 'threat to sense of control.' The inclusion of item R12 ('You have to speak to a dental nurse about changing her procedures in the dental surgery') may reflect that dentists work in idiosyncratic ways and good team work is essential to the efficient running of the surgery; lack of cooperation from the dental nurse would result in stress for the dentist. It may also reflect the pressure of managing staff in order to meet the rigours of contemporaneous standards and guidelines.

Treating anxious and phobic patients has long been noted as a significant stressor36,50 and research suggests that some dentists feel ill equipped to help these patients.50

The conflicts created by having to charge patients for healthcare, most of which is free at the point of delivery in the UK, are reflected in the scale 'ethical conflicts' and confirms previous findings.6,7 The dentists who work largely in NHS practice are more likely to be affected by these issues, though no analysis was undertaken to demonstrate this.

The study had a number of limitations. The return rate of 34.1%, which resulted in a usable form rate of 23.6%, was disappointing and may have impacted on the generalisability of the study. The large number of 'return to sender' items (some received up to 9 months after the deadline for the return of the second questionnaire) suggests that the GDC register is not accurate, resulting in a sampling error beyond the control of the research team.51,52 The forms sent to dentists who were retired or not working in primary care, who are largely unidentifiable via the register, resulted in another sampling error beyond the team's control. The offer of entry to a prize draw, for one of five £20 vouchers, may have been insufficient incentive to dentists to participate.51,52 The response rate may have been affected by the length of the questionnaire pack or the attitude of the dentists to the survey.51,52 One dentist emailed the researchers to state: 'Unfortunately I cannot complete this survey as the question[s] asked in too many cases show a lack of understanding of what actually happens in a dental surgery thus making the answers impossible to answer.'

This attitude may have been fostered by the fact that the questionnaire came from a team based in a university which does not have a track record in dental research and thus the project may have been viewed as of little value.51,52

Return rates could have been improved with a third send, but this was beyond the financial resources of the project.

Despite the low return rate, levels of burnout seen were typical of the population, suggesting the sample was representative.51 However, the study warrants replication with a further sample.

The pattern of missing data from the DACSS-C may be for at least two reasons; many participants endorsed 'Yes they did change what they did' to most items. It may have been that they felt that it was unnecessary to keep stating that this happened, or, more likely, the realisation that anxiety made them change how they worked in numerous situations may have been threatening and they felt vulnerable to being perceived as being incompetent because of this. This pattern might be reduced in future by changing the wording of the introduction to assure dentists that changing one's clinical treatment can be highly appropriate and isn't necessarily an indication of incompetence. It would be interesting to ask this question of a sample of dentists to establish if this is a possible outcome. Or, more simply, it may have been that, at 20 items, the questionnaire was too long and the participants experienced response fatigue.53

The exclusion from the final analysis of salaried dentists, as a result of questions DACSS-R18–R20, suggests that the study should be replicated with a large sample of this type of dentist as research has shown7 that they are subject to additional specific stressors such as working in isolation and being the end point for referral, rather than able to refer on in difficult cases. The decision to group questions R18–R20 at the end of the study was based on feedback from the dentists who completed the pilot version of the questionnaire, where the items were interspersed. It is suggested that, in subsequent use of the measure, the instructions for completion of these items is changed from, 'Questions 18–20: Only worked in salaried services? – please ignore,' to Questions 18–20: Never had to charge patients for treatment? – please ignore.' This should minimise the number of salaried dentists who do not complete these items; the caveat must remain as some dentists do not charge patients for care. To remove the items would be to remove questions about significant stressors for the majority of dentists.

The described examples of anxiety-provoking situations and consequences for decision-making revealed a range of situations including stressors related to patient characteristics, treatment, workload and communication, confirming the factors elicited and described in previous research.6,7,8,36

Conclusion

This study reports the development of a reliable measure of dentists' anxiety in clinical situations – the DACSS, which should prove useful in further research into absolute levels of anxiety and in monitoring change following clinical stress interventions for dentists.

The association of DACSS scores with burnout (positively with emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation and negatively associated with personal achievement) suggests that interventions to tackle anxiety may improve burnout and vice versa.

The association of dentists' anxiety with decision-making style (negatively with decision-making self-esteem and vigilant decision-making and positively with hypervigilant and avoidant decision-making) implies that improving dentists' abilities to cope with difficult situations may improve decision-making. The much weaker relationship with the decisional action scale of the Dealing with Uncertainty Scale, suggests that the impact of anxiety on dentists' decisions is, at least partly, out of awareness and opens the possibility for interventions to improve decisional awareness and thus patient outcomes.

References

Denton D A, Newton J T, Bower E J . Occupational burnout and work engagement: a national survey of dentists in the United Kingdom. Br Dent J 2008; 205, E13E13.

Cooper C L, Watts J, Baglioni A J, Kelly M . Occupational stress among general practice dentists. J Occup Organ Psychol 1988; 61: 163–174.

Osborne D, Croucher R . Levels of burnout in general dental practitioners in the south-east of England. Br. Dent J 1994; 177: 372–377.

Moller A T, Spangenberg J J . Stress and coping among South African dentists in private practice. J Dent Assoc S Afr 1996; 51: 347–357.

Lazarus R S, Folkman S . Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company, 1984.

Bretherton R, Chapman H R, Chipchase S . A study to explore specific stressors and coping strategies in primary dental care practice. Br Dent J 2016; 220: 471–478.

Chapman H R, Chipchase S Y, Bretherton R . Understanding emotionally relevant situations in primary care dental practice: 1. Clinical situations and emotional responses. Br Dent J 2015; 219: 401–409.

Chapman H R, Chipchase S Y, Bretherton R . Understanding emotionally relevant situations in primary dental practice. 2. Reported effects of emotionally charged situations. Br Dent J 2015; 219, E8.

Gorter R C, Albrecht, G, Hoogstraten J, Eijkman M A . Professional burnout among Dutch dentists. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1999; 27: 109–116.

Maslach C, Schaufeli W B, Leiter M P . Job Burnout. Annu Rev Psychol 2001; 52: 397–422.

te Brake J H, Bouman A M, Gorter R C, Hoogstraten J, Eijkman M A . Using the Maslach Burnout Inventory among dentists: burnout measurement and trends. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2008; 36: 69–75.

Leiter M P, Maslach C . Six areas of worklife: a model of the organizational context of burnout. J Health Hum Serv Adm 1999; 21: 472–489.

Maslach C, Jackson S, E, Leiter M et al. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Menlo Park, California: Mind Garden Inc, 1986.

te Brake H, Smits N, Wicherts J M, Gorter R C, Hoogstraten J . Burnout development among dentists: a longitudinal study. Eur J Oral Sci 2008; 116: 545–551.

Bakker A B, Schaufeli W B, Sixma H J, Bosveld W, van Dierendonck D . Patient demands, lack of reciprocity, and burnout: A five-year longitudinal study among general practitioners. J Organ Beh 2000; 21: 425–441.

Taris T W, Le Blanc P M, Schaufeli W B, Schreurs P J G . Are there causal relationships between the dimensions of the Maslach Burnout Inventory? A review and two longitudinal tests. Work & Stress 2005; 19: 238–255.

Deligkaris P, Panagopoulou E, Montgomery A J, Masoura E . Job burnout and cognitive functioning: A systematic review. Work & Stress 2014; 28: 107–123.

Shanafelt T D, Balch C M, Bechamps G et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg 2010; 251: 995–1000.

West C P, Huschka M M, Novotny P J et al. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy. JAMA 2006; 296: 1071–1078.

Balch C M, Freischlag J A, Shanafelt T D . Stress and burnout among surgeons: understanding and managing the syndrome and avoiding the adverse consequences. Arch Surg 2009; 144: 371–376.

Osterberg K, Skogsliden S, Karlson B . Neuropsychological sequelae of work-stress-related exhaustion. Stress 2014; 17: 59–69.

Arora S, Sevdalis N, Nestel D, Woloshynowych M, Darzi A, Kneebone R . The impact of stress on surgical performance: a systematic review of the literature. Surgery 2010; 147: 318–330, 330.

Tsutsumi A, Umehara K, Ono H, Kawakami N . Types of psychosocial job demands and adverse events due to dental mismanagement: a cross sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2007; 7: 3.

Janis I L, Mann L . Decision making: a psychological analysis of conflict, choice, and commitment. New York: The Free Press, 1977.

Anderson C J . The psychology of doing nothing: Forms of decision avoidance result from reason and emotion. Psychol Bull 2003; 129: 139–167.

Mann L, Burnett P, Radford M, Ford S . The Melbourne Decision Making Questionnaire: An instrument for measuring patterns for coping with decisional conflict. J Behav Decis Mak 1997; 10: 1–19.

Mann L, Radford M, Burnett P et al. Cross-cultural differences in self-reported decision-making style and confidence. Int J Psychol 1998; 33: 325–335.

O'Connor A M . Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Mak 1995; 15: 25–30.

Dolan J G . A method for evaluating health care providers' decision making: The provider decision process assessment instrument. Med Decis Mak 1991; 19: 38–41.

LeBlanc A, Kenny D A, O'Connor A M, Legare F . Decisional conflict in patients and their physicians: A dyadic approach to shared decision making. Med Decis Mak 2009; 29: 61–68.

McGee R A . Burnout and professional decision making: An analogue study. J Couns Psychol 1989; 36: 345–351.

Croskerry P, Abbass A A, Wu A W . How doctors feel: Affective issues in patients' safety. The Lancet 2008; 372: 1205–1206.

Croskerry P . Clinical cognition and diagnostic error: Applications of a dual process model of reasoning. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2009; 14: 27–35.

Schneider A, Löwe B, Barie S, Joos S, Engeser P, Szecsenyi J . How do primary care doctors deal with uncertainty in making diagnostic decisions? The development of the 'Dealing with Uncertainty Questionnaire' (DUQ). J Eval Clin Pract 2010; 16: 431–437.

Gilmour J, Stewardson D.A, Shugars D A, Burke F J . An assessment of career satisfaction among a group of general dental practitioners in Staffordshire. Br Dent J 2005; 198: 701–704, discussion.

Gorter R C . Stress and burnout in dentistry: a review of the literature. pp 13–44. University of Virginia, 2000. Thesis.

Field A . Discovering statistics using SPSS. London: Sage Publications Ltd, 2009.

Gorter R C, Albrecht G, Hoogstraten J, Eijkman M A . Measuring work stress among Dutch dentists. Int Dent J 1999; 49: 144–152.

Humphris G M, Cooper C L . New stressors for GDPs in the past ten years: a qualitative study. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 404–406.

Mann L, Tan C . The hassled decision maker: The effects of perceived time pressure on information processing in decision making. Aus J Management (University of New South Wales) 1993; 18: 197.

Turnipseed D L . Anxiety and burnout in the health care work environment. Psychol Rep 1998; 82: 627–642.

Organopoulou M, Tsironi M, Malliarou M, Alikari V, Zyga S . Investigation of anxiety and burn-out in medical and nursing staff of public hospitals of Peloponnese. Int J Caring Sci 2014; 7: 799–808.

Lee W, Veach P M, MacFarlane I M, LeRoy B S . Who is at risk for compassion fatigue? An investigation of genetic counselor demographics, anxiety, compassion satisfaction, and burnout. J Genet Counse 2015; 24: 358–370.

Khatami S, MacEntee M I, Pratt D D, Collins J B . Clinical reasoning in dentistry: a conceptual framework for dental education. J Dent Educ 2012; 76: 1116–1128.

Schaufeli W B, Maassen G H, Bakker A B, Sixma H J . Stability and change in burnout: A 10-year follow-up study among primary care physicians. J Occup Organ Psychol 2011; 84: 248–267.

Chapple H, Shah S, Caress A L, Kay E J . Exploring dental patients' preferred roles in treatment decision-making – a novel approach. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 321–327.

Richards H J, Benson V, Donnelly N, Hadwin J A . Exploring the function of selective attention and hypervigilance for threat in anxiety. Clin Psychol Rev 2014; 34: 1–13.

Kimble M, Boxwala M, Bean W et al. The impact of hypervigilance: Evidence for a forward feedback loop. J Anxiety Disord 2014; 28: 241–245.

Chambers D W . The role of dentists in dentistry. J Dent Educ 2001; 65: 1430–1440.

Moore R, Brodsgaard I . Dentists' perceived stress and its relation to perceptions about anxious patients. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2001; 29: 73–80.

Dillman D A . The design and administration of mail surveys. Ann Rev Sociol 1991; 17: 225–249.

Edwards P J, Roberts I, Clarke M J et al. Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; Mr000008.

Ben-Nun P . Respondent fatigue. In Encyclopaedia of survey research methods. Lavrakas P J (ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. 2008.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to the Shirley Glasstone Hughes Trust for funding this project and to the dentists who gave generously of their precious time. The authors would also like to acknowledge the advice of Professors Leon Mann, Pat Croskerry and Patricia Hollen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chipchase, S., Chapman, H. & Bretherton, R. A study to explore if dentists' anxiety affects their clinical decision-making. Br Dent J 222, 277–290 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.173

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.173

This article is cited by

-

Patient safety in dentistry - the bigger picture

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

Mental health and wellbeing interventions in the dental sector: a systematic review

Evidence-Based Dentistry (2022)

-

Does workplace social capital predict care quality through job satisfaction and stress at the clinic? A prospective study

BMC Public Health (2021)

-

Supporting dentists' health and wellbeing - a qualitative study of coping strategies in 'normal times'

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Entscheidungstendenzen als psychoemotionale Einflussfaktoren auf das selbsteingeschätzte unterrichtliche Planungsverhalten angehender Lehrkräfte

Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft (2021)