Key Points

-

Provides a detailed description of the extent and nature of direct access care.

-

Demonstrates that advantages and disadvantages for both patients and clinicians are reported.

-

Describes limitations and barriers to direct access provision.

-

Discusses the impact on clinical skills and autonomy.

Abstract

Aim The aim of this study was to identify and survey dental hygienists and therapists working in direct access practices in the UK, obtain their views on its benefits and disadvantages, establish which treatments they provided, and what barriers they had encountered.

Method The study used a purposive sample of GDC-registered hygienists and therapists working in practices offering direct access, identified through a 'Google' search. An online survey was set up through the University of Edinburgh, and non-responses followed up by post.

Results The initial search identified 243 individuals working in direct access practices. Where a practice listed more than one hygienist/therapist, one was randomly selected. This gave a total of 179 potential respondents. Eighty-six responses were received, representing a response rate of 48%. A large majority of respondents (58, 73%) were favourable in their view of the GDC decision to allow direct access, and most thought advantages outnumbered disadvantages for patients, hygienists, therapists and dentists. There were no statistically significant differences in views between hygienists and therapists. Although direct access patients formed a small minority of their caseload for most respondents, it is estimated that on average respondents saw approximately 13 per month. Treatment was mainly restricted to periodontal work, irrespective of whether the respondent was singly or dually qualified. One third of respondents reported encountering barriers to successful practice, including issues relating to teamwork and dentists' unfavourable attitudes. However, almost two thirds (64%) felt that direct access had enhanced their job satisfaction, and 45% felt their clinical skills had increased.

Discussion Comments were mainly positive, but sometimes raised worrying issues, for example in respect to training, lack of dental nurse support and the limited availability of periodontal treatment under NHS regulations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is now approaching four years since the General Dental Council (GDC) abolished the requirement for a referral from a dentist before a patient could see a dental hygienist or therapist for treatment.1,2 However, there is evidence that many dentists remain concerned about certain aspects of direct access. A survey conducted in 2014 among a representative sample of dentists found that most held unfavourable views with regard to hygienists and dually qualified hygienist/therapists undertaking diagnosis and treatment planning, risk assessments, referral decisions and, for therapists, restorations, despite the fact that these activities were within their respective scope of practice.3 These findings mirror those of an earlier study which indicated that dentists were concerned about the education, competence and ability of hygienists and therapists to undertake treatments which had been previously viewed as only within the scope of practice of dentists.4 However, studies in the UK and elsewhere suggest that such fears may be ill-founded.5,6,7,8

There remains a lack of information on how widespread direct access has become in the UK, or how it is operating. The aim of this study was therefore to investigate how hygienists and therapists working in direct access practices were functioning within the new system, which treatments were involved, and what barriers they had encountered. For brevity the terms 'dental hygienists' and 'dental therapists' are used here, although the dental therapists of today are dually qualified in dental hygiene and dental therapy.

Method

The study used a purposive sample of hygienists and therapists working in practices offering direct access. Such practices were identified by conducting a 'Google' search using the terms 'dental direct access', 'dental hygienist direct access', 'dental hygiene direct access' and, 'dental therapist direct access'. The particulars of UK-based practices so identified were then noted, and the website of each practice was searched in order to obtain names of hygienists and therapists employed there. Although it would have been possible to email these practices requesting cooperation, it was felt to be preferable to use the individual hygienists' or therapists' email address when requesting participation. These addresses were obtained by referencing the UK GDC Register, to which the authors were given access under strict conditions of use and confidentiality. Where two or more hygienists and/or therapists were found to be working at the same practice address, one was selected using an online random number generator (https://www.random.org/). This search was supplemented by reference to the 'Hygienist Direct' website, which lists a number of stand-alone clinics or dentist-led practices offering direct access (http://www.hygienistdirect.co.uk/).

A questionnaire was developed and piloted. As the survey was targeted at all known hygienists and therapists offering direct patient access, it was not possible to draw a pilot sample without reducing the number of potential respondents. A number of colleagues at Edinburgh Dental Institute were therefore asked to access and complete the online survey. The design and content of the questionnaire was guided by previous surveys of general dental practitioners conducted by the authors.3,4 It used both closed and open-ended questions, and covered issues relating to direct patient access to hygienists and therapists within the context of their respective scope of practice, including periodontal and preventive treatment, oral health advice, referral for treatment by a dentist and, for therapists, restorative treatment. Opinion questions were investigated using five-point scales ('very favourable, quite favourable, neutral, quite unfavourable, very unfavourable'; or 'very much agree, somewhat agree, neither, somewhat disagree, very much disagree', plus 'can't say'. A validated measure of job satisfaction was included.9 The survey may be accessed through the link provided at the end of this article.

In November 2015 those hygienists and therapists identified as working in direct access practices were sent an email introducing the study which contained a hyperlink unique to that individual through which the online questionnaire could be accessed.10 An email reminder to non-respondents was followed by a mailed paper questionnaire sent two weeks after the original communication, and a final reminder/thank you email was sent in early January 2016 to all included in the original communication. Analysis was conducted using SPSS V22.11 Differences in views between hygienists and others were tested using the chi-square, the Mann-Whitney test or student's t test at the P = 0.05 level. Where none were found, results for both hygienists and therapists are reported together.

Results

The initial search identified 243 individuals working in practices offering direct access. While many practices appeared to be stand-alone businesses, a number were part of a corporate group of up to 50 practices all offering direct access dental hygiene services. Where a practice at a unique address listed more than one hygienist/therapist, one was randomly selected as described above. This gave a total of 179 potential respondents. Sixty online and 26 postal responses were received, representing a response rate of 48%.

The 86 respondents included 52 singly qualified dental hygienists (60%), 32 dually qualified hygienist/therapists (37%), and two singly qualified therapists (2%). This breakdown closely reflects the make-up of the GDC register, where singly qualified dental hygienists represent 68% of UKbased dental hygienists and therapists.

The majority of respondents, 74 (86%), worked in England, three (6%) in Scotland, and seven (8%) in Wales. Forty-three (50%) worked full time (including one who only ran an oral hygiene website), 42 (49%) worked part time (ie four days or less), and one (1%) was not currently working. Fifty-seven (66%) reported that they worked in all or mainly private practice, 23 (27%) worked in practices that were 50/50 private and NHS, and two (2%) worked in mainly or all NHS practices.

Views on direct access

A large majority of respondents (58, 73%) reported that they were very favourable in their view of the GDC decision to allow direct access (Fig. 1).

When asked whether they thought there were any advantages or disadvantages of direct access for patients, 83 (96%) said there were advantages, and 36 (42%) stated there were disadvantages (Fig. 2).

A large majority (70, 81%) also thought there were advantages for hygienists and therapists (Fig. 3).

Similarly, most (69, 80%) thought there were advantages for dentists (Fig. 4).

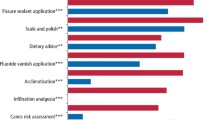

Respondents were then asked their views on the likely impact of direct access on eight aspects of dental care (Fig. 5).

Experience of direct access

Six (7%) of the respondents reported that they did not currently offer direct access care, although, all but one of these said they planned to do so in the next two years. The remaining 80 were asked a series of questions about their practice.

For the large majority (72 of 80, 90%), direct access patients formed a small minority of their caseload. Sixteen (21%) reported they saw fewer than one direct access patient per month, and another 42 (54%) estimated that they saw between one and nine per month. At the other extreme, 10% (8) stated they saw 40 or more direct access patients per month, with a maximum of 220 reported. The mean number seen by the 78 who were able to estimate the number of direct access patients they saw per month was 13.1. There is some evidence that numbers seen may have built up over time. The 31 who said they had been offering direct access for over two years reported seeing a mean of 18.0 patients per month, compared to a mean of 5.4 among the 46 who had started direct access more recently (t = 2.17, df 33.58, P = 0.04).

There is also evidence that direct access patients may include considerable numbers who were not previously registered with a practice. Of the respondents, 27 (34%) said that half or more of new direct access patients were not registered with a practice, and only 17 (21%) said that all or most of their new direct access patients were already registered with the practice where the hygienist or therapist was working.

Practising arrangements

Practising arrangements were unchanged for the majority of respondents (60 of 80 – 75%), while 11 (14%) had established a direct access list within their current dentist-owned practice, six (8%) had their own set of fees, and four (6%) were in independent practice. Nine (11%) described these arrangements (Table 1).

Participants were asked how patients were referred to a dentist for treatment outside their own scope of practice. Sixty one (86%) said they referred to a dentist within their practice, 55 (64%) advised the patient to attend their own practice without making a formal referral, and 11 (13%) had a formal arrangement with an outside dental practice. Eight (10%) made comments about their referral arrangements (see online supplementary material, Appendix 1a).

Treatment was mainly restricted to periodontal work, irrespective of whether the respondent was singly or dually qualified. Twenty one of 33 (64%) dually qualified hygienist-therapists and 37 of 53 (70%) singly qualified hygienists said their direct access work was only periodontal in nature.

Barriers

Twenty-six of the 80 (33%) respondents reported encountering barriers to successful practice (Fig. 6).

As these reports of barriers encountered may be particularly helpful in regard to the future development of direct access, Table 2 shows the comments in full under the four headings given in Figure 6.

Training and support needs

Eighteen (21%) felt their education and training had not prepared them sufficiently to see patients under direct access. Seven comments referred to training in diagnosis or screening skills, while 11 made more general points about training to improve the skills needed to work more independently (see online supplementary material, Appendix Table ii). However, there was no difference between the eight hygienists who felt unprepared for direct access by their training in terms of the number of years since they had qualified or the level of confidence they felt undertaking treatments without a dentist's prescription. However, the ten therapists who were critical of their training in this respect reported a significantly lower level of confidence undertaking ten specified treatments (diagnose and treatment plan – perio, apply fissure sealants, administer local analgesia, assign recall intervals, take radiographs, diagnose and treatment plan – restorative, restore primary teeth, restore permanent teeth, extract primary teeth and undertake risk assessments) without a dentist's prescription than those who were uncritical of their training (t = 2.69, df 31, p = 0.01).

Fifty-five (64%) felt that hygienists and therapists working under direct access arrangements needed additional support, and made 57 comments between them (Fig. 7 and online supplementary material, Appendix Table iii).

Patients' views

Respondents were asked what they felt their patients' views of direct access were, using a five point scale from very favourable to very unfavourable. Fifty two (65%) said their patients were very favourable, and another 21 (26%) said they were quite favourable. No unfavourable views were reported.

NHS List numbers

Asked their view on whether the current restriction on hygienists and therapists accessing an NHS List Number, 54 (63%) felt this restriction should be removed, five (6%) said it should not, and 26 (30%) were unsure or had no view.

Skills and job satisfaction

Asked if working under direct access arrangements had any impact on their clinical skills, 16 (20%) stated these had been enhanced considerably, 20 (25%) said they had been enhanced a little, and 42 (52%) said there had been no impact. Comments made are listed in Appendix Table iv (online only supplementary material). Twenty (25%) reported that direct access had enhanced their job satisfaction by a lot, 31 (39%) by a little, and 25 (31%) said it had no impact. Two (2%) felt it had decreased their job satisfaction a little.

On a 7-point scale, with one representing extreme dissatisfaction and seven extreme satisfaction with their job, 67 of 80 (84%) scored five or more. Across all respondents dental hygienists had a higher mean job satisfaction score than therapists (5.92, n = 50; 5.30, n = 33: p = 0.02). However this was not the case when the analysis was restricted to those 80 providing direct access (5.89, n = 47; 5.37, n = 30: p = 0.06).

Discussion

As far as is known, this study represents the first review of direct access in the UK since the GDC reform of 2013. Responses were qualitatively very rich. The main weaknesses to this study are the survey frame and the response rate. Use of a web search to identify direct access practices employing hygienists and therapists is likely to yield few false positives but may have led to an unknown number of false negatives if reference to direct access on practice websites was scant. Given that direct access appeared to be concentrated in private practice, with strong incentives to attract income from new patients, it is possible that the internet search method used may be less likely to miss eligible practices than if the same approach was adopted if and when direct access is extended to NHS dental services. It could also be argued that only including hygienists and therapists in the survey, and excluding dentists and patients, gives an incomplete picture of the impact of direct access. The authors hope to address this point in future work, which will build on the study of dentists' attitudes to direct access completed in 2014.3 The justification for focusing on hygienists and therapists exclusively at this point is that these are the clinicians most directly involved in the reform, and their experiences, will inform future work involving dentists and patients.

A response rate of 48% (86 of 179) to a mixed methods survey may be considered reasonably good compared with similar recent surveys and research findings on the subject.12,13,14,15,16It is possible that monetary incentives and/or telephone follow-up may have increased the response rate further, but these options were ruled out on resource grounds.17,18

The initial August 2015 search identified almost 250 individuals working in direct access practices. If the 80 direct access-active survey respondents are representative of this larger number, their experience suggests that by the end of 2015 at least 3,000 patients were being treated every month under direct access arrangements.

In a recent review, Brocklehurst et al. suggested that the purpose of direct access type reforms remained unclear: 'Is it to expand access, reduce inequalities in access, improve quality of care, improve population health, or reduce costs?'

Comments from respondents in this study refer to all these potential benefits. For example, responses reviewed in Figure 4 and Table 1 on attracting new patients to the practice suggests that direct access may indeed be able to stimulate the dental market, or change the consumer profile of service users by bringing new or reluctant patients into the surgery on a regular basis. However, a smaller number also referred to the possibility that some patients may be deterred from continued attendance if their treatment is poorly managed between team members (see online supplementary material, Appendix Table i).

Direct access to dental hygienists has been available in the US on a state by state basis since the 1980s.20 Similar arrangements are well established in New Zealand, the Netherlands and elsewhere. Northcott et al., in a qualitative study of direct access arrangements in the Netherlands, reported similar concerns regarding teamwork, public perceptions and referral arrangements etc as those voiced by the hygienists and therapists in the present study.21 In the example of how patients are referred by hygienists and therapists if required, the GDC has not issued prescriptive guidance but suggests individual practices establish their own procedures:

'Dental hygienists and dental therapists offering treatment via direct access need to have clear arrangements in place to refer patients on who need treatment which they cannot provide. In a multi-disciplinary practice where the dental team works together on one site, this should be straightforward. In a multi-site set-up where members of the dental team work in separate locations, there should be formal arrangements such as standard operating procedures in place for the transfer and updating of records, referrals and communication between the registrants.'1

Direct access is not currently possible within the terms of the NHS GDS contract without changes in either regulations (England and Wales) or primary legislation (Scotland and Northern Ireland),22 which require a full oral health assessment to be carried out by a dentist. A majority of the hygienists and therapists in this study felt this restriction should be revoked. For direct access to function in the NHS and to completely fulfil its original purpose, there is a need for hygienists and therapists to be allocated NHS list or provider numbers as a matter of urgency. Until this is addressed, direct access will only function in a limited way and deny professionals the autonomy they deserve, and patients the right to choose who carries out their treatment. Such a reform would permit a great expansion in the numbers of practitioners providing treatment under direct access, and greatly increase the gateway to dental services among many in the population, whether or not they are currently registered with a practice. Another fundamental barrier is the inability to prescribe medicines, particularly local analgesia and fluoride. This restriction dictates that hygienists and therapists will never have complete autonomy in terms of treatment provision although still working as part of a team, which was the purpose of direct access in the first instance. Under the current regulations, these clinicians will have to rely on individual prescriptions from dentists or patient group directives to administer these essential components of everyday patient treatment and care.

Individual comments made by respondents were enlightening and sometimes rather worrying. The lack of allocation of dental nurses to hygienists and therapists was highlighted, as was the unavailability of periodontal treatment under NHS regulations in some areas. A comment of concern was made in relation to the length of appointment times in order to write notes in enough detail and comply with GDC Regulations (Table 2). Anecdotally, ten to fifteen minute appointments are routine for many hygienists and therapists, and often nursing support is not available. It is clearly not in the best interest of either the patient or clinician to have to work under these circumstances. Conversely, many participants reported that they were satisfied with their employment arrangements, demonstrating that skill mix can be successful if utilised to its full extent. If the clinical abilities of hygienists and therapists were to be underused, there is a risk of them becoming deskilled, representing a huge waste in terms of resources, and a demoralising and frustrating situation for the individual. The survey found that much work with direct access patients was periodontal in nature, one result of which be the lower job satisfaction reported by dental therapists in this study

Conclusion

This survey revealed strongly positive views regarding direct access among hygienists and therapists practicing under the new arrangements, tempered by some frustration in respect to the level of referrals, the nature of the clinical work they had to undertake, and a certain lack of recognition of their contribution and potential by dental colleagues. Dangers of de-skilling and demoralisation are evident. However, the barriers they report are not insurmountable, given professional and political commitment. Direct access for patients may be the most radical reform to have ever taken place in dentistry in the UK, and it is clear that it requires time and support to become embedded on our healthcare system for the future benefit of the population. As one respondent to the survey commented: 'There are many patients who as a result of DA have better oral health and are also more likely to then go on to receive further treatment. Seems to be a win-win decision' (online supplementary material, Appendix: table v).

Link to survey: https://edinburgh.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/direct-patient-access-3

References

General Dental Council. Guidance on direct access. 2013. Available online at http://www.gdc-uk.org/Newsandpublications/factsandfigures/Documents/Direct%20Access%20guidance%20UD%20May%202014.pdf (accessed November 2015).

Quinlan K . GDC announces controversial decision on direct access. Br Dent J 2013; 214: 379.

Ross M, Turner S . Direct access in the UK: what do dentists really think? Br Dent J 2015; 218: 641–647.

Ross, M K, Ibbetson, R, Turner S . The acceptability of dually-qualified dental hygienist-therapists by General Dental Practitioners in South East Scotland. Br Dent J 2007; 202: 146–147.

Turner S, Tripathee S, Macgillivray S . Direct access to DCPs: what are the potential risks and benefits? Br Dent J 2013; 215: 577–582.

Macey R, Glenny A, Walsh T, Tickle M, Worthington H, Ashley J, Brocklehurst P . The efficacy of screening for common dental diseases by hygiene-therapists: a diagnostic test accuracy study. J Dent Res 2015; 94: 70S–708S.

Naughton D . Expanding oral care opportunities: Direct access provided by dental hygienists in the United States. J Evid Base Dent Pract 2014; 145: 171–182.

Laurant M, Reeves D, Hermens R, Braspenning J, Grol R, Sibbald B . Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; CD001271.

Warr P, Cook J, Wall T Scales for the measurement of some work attitudes and aspects of psychological well-being J Occ Psych 1979; 52: 129–148.

Bristol Online Surveys. Available online at http://www.survey.bris.ac.uk (accessed January 2017).

IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Hardigan P C, Succar C T, Fleisher J M . An analysis of response rate and economic costs between mail and web-based surveys among practicing dentists: a randomized trial J Community Health 2012; 37: 383–394.

Cook J V, Dickinson H O, Eccles M P . Response rates in postal surveys of healthcare professionals between 1996 and 2005: an observational study. BMC Health Serv Res 2009; 9: 160.

Shelly A M, Brunton P, Horner K . Questionnaire surveys of dentists on radiology. Dentomaxillofacial Radiology 2012; 41: 267–275.

Parashos P, Morgan M V, Messer H H . Response rate and nonresponse bias in a questionnaire survey of dentists. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2005; 33: 9–16.

Locker D . Response and nonresponse bias in oral health surveys. J Public Health Dent 2000; 60: 72–81.

Glidewell L, Thomas R, MacLennan G et al. Do incentives, reminders or reduced burden improve healthcare professional response rates in postal questionnaires? Two randomized controlled trials: BMC Health Services Research 2012; 12: 250.

Edwards PJ, Roberts I, Clarke M J et al. Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Systematic Rev 2009; MR000008.

Brocklehurst P, Jerkovic-Cosic K, Tickle M Direct access to midlevel dental providers: an evidence synthesis. J Pub Health Dent 2014; 74: 326–335.

Dyer T, Brocklehurst P, Glenny A M, Davies L, Tickle M, Issac A, Robinson PG Dental auxiliaries for dental care traditionally provided by dentists. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; 8: CD010076.

Northcott A, Brocklehurst P, Jerković-Ćosić K . Reinders J J, McDermott I, Tickle M Direct access: lessons learnt from the Netherlands Br Dent J 2013; 215: 607–610.

BDA. Direct access to Dental Care Professionals. 2015. Availble online at https://www.bda.org/dentists/policy-campaigns/research/bda-policy/briefings/PublishingImages/hot-topics/Hot%20Topic%20-%20Direct%20Access%202015.pdf (accessed January 2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

MR was involved in the lobby for direct access by the British Society of Dental Hygiene and Therapy. She is also a past President of the same Society.

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

supplementary material (PDF 121 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Turner, S., Ross, M. Direct access: how is it working?. Br Dent J 222, 191–197 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.123

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.123

This article is cited by

-

A survey of mental wellbeing and stress among dental therapists and hygienists in South West England

BDJ Team (2023)

-

A survey of mental wellbeing and stress among dental therapists and hygienists in South West England

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

Participation of paediatric patients in primary dental care before and after a dental general anaesthetic

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2021)

-

Are dental schools doing enough to prepare dental hygiene & therapy students for direct access?

BDJ Team (2020)

-

A whole-team approach to optimising general dental practice teamwork: development of the Skills Optimisation Self-Evaluation Toolkit (SOSET)

British Dental Journal (2020)