Key Points

-

Highlights that people experiencing homelessness suffer a disproportionate burden of oral disease that can impact on their quality of life and may lead to the use of drugs or alcohol to manage their dental problems.

-

Notes that three quarters of the Crisis at Christmas service users did not access any other dental care throughout the year.

-

Shows that patient satisfaction with the Crisis at Christmas dental service has been consistently high with almost all guests satisfied with the dental treatment they received and willing to recommend the service to others.

Abstract

Background The UK charity Crisis originated in 1967 as a response to the increasing numbers of homeless people in London, and the first Crisis at Christmas event for rough sleepers was established in 1971. Since then, Crisis has provided numerous services over the Christmas period to the most vulnerable members of society. One of these is the Crisis at Christmas Dental Service (CCDS) which provides emergency and routine dental care from 23–29 of December each year. The charity is entirely dependent on voluntary staffing and industry donations including materials and facilities. This paper aims to assess the impact of the service over the last six years of clinical activity from 2011–2016.

Method Anonymised data were collected from the annual CCDS delivered over the last six consecutive years. Services included: dental consultations; oral hygiene instruction; scale and polishes; permanent fillings; extractions; and fluoride varnish applications. In addition, anonymised patient feedback was collected after each dental attendance.

Results On average, 80–85% of the patients were male and the majority were between 21 and 60 years of age. The most common nationality was British (46%). Over the six-year data collection period intervention treatments (restorations and extractions) remained fairly consistent, while the number of fluoride varnish applications and oral hygiene instruction have increased. The majority of patients reported positive satisfaction with their treatment and would have recommended the service to others. Approximately 75% of patients did not regularly attend a dentist outside of Crisis and a similar proportion were given information on where to access year round dental services for homeless people in London. The majority of dental volunteers felt that they enjoyed the experience and would consider volunteering again for Crisis in the future.

Conclusion The Crisis at Christmas Dental Service has emerged as a valuable asset to the portfolio of resources accessible to vulnerable, marginalised people over the Christmas period and exposes the high dental need of the homeless population of London.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Crisis at Christmas, the national charity for single homeless people, originated in 1967 as a response to the increasing numbers of homeless people for whom very limited support and services were available. Crisis at Christmas provides a range of volunteer-led services to the homeless and vulnerably housed population group over the Christmas period; dentistry is one of over 20 services available for people to access.

Each year the Crisis at Christmas Dental Service (CCDS) draws in vast numbers of GDC registered volunteers from around the UK: dentists; therapists; hygienists; and dental nurses, who wish to share their festive season with the homeless and vulnerably-housed population of the capital. The dental service has been operating since 1995 and has grown in capacity to accommodate over 400 patients each year. Dental patients are signposted to the service by volunteers at each of the ten Crisis at Christmas centres, five of which are residential centres for the most vulnerable people who have nowhere to sleep at night, the remaining five are day centres for hidden homeless people whom may be in temporary accommodation such as hostels, night shelters, bed and breakfasts, living in squats, or sofa-surfing with friends or relatives. The dental team currently operates every day from 23–29 of December from four fully equipped mobile dental units situated at two bases in North and South London. Every morning patients attending the North and South dental bases are seen by the dental team. At other centres, patients are triaged by the visiting dental volunteer team and subsequently transported from these centres to the North and South dental bases for afternoon treatment sessions. The treatments are limited to simple interventions which can feasibly be provided within the confines of a mobile dental unit. The aim is to treat the patient's presenting complaint, which generally ranges from a dental checkup and a scale and polish, to pain relief and extraction of teeth. The CCDS does not provide complex treatments that would require multiple visits or laboratory facilities, such as crowns, bridges, dentures or implants; this limitation is made clear to patients when registering to attend the dental service.

This service evaluation will review and summarise the patient contacts and treatments provided over a six-year period (2011–2016) and discuss the feedback collated from patients who have received dental care.

Homelessness and oral health

In the UK, homelessness has increased by 37% since 2010 and rough sleeping in England increased by 16% in 2016.1 People who experience homelessness include those who are visibly roofless such as rough sleepers, as well as those in temporary accommodation as described previously.2 More recently, this definition has been extended to include those seeking asylum as a result of political conflicts and persecution. People who are house-sharing in unreasonable circumstances, with insecure tenure or facing eviction, may also be deemed as 'being at risk' of becoming homeless.3

The majority of those accessing dental services for homeless people are males (87%) between 23 and 61 years of age and of caucasian origin (84%).4 The normative need for dental care has been found to be extensive in the homeless population. Daly et al. found in a survey of 102 homeless and vulnerably-housed people that 76% had broken teeth, 80% would have benefited from oral hygiene measures or periodontal treatment, and 38% had a prosthetic treatment need.5 The commonest oral health impact reported by the group was oral pain; 65% had 'aching' in the mouth and 62% had felt 'discomfort' when eating. Groundswell homeless charity interviewed 260 people experiencing homelessness in London and found that only 39% of participants had attended a dentist in the last year despite 56% having bleeding gums, 46% having holes in their teeth and 26% experiencing dental abscesses.6 In this population, 29% of people cleaned their teeth less than once per day. It is acknowledged that the homeless population have a greater number of missing and decayed teeth than the national average and this is due to a multifactorial aetiology.7 The major barriers to regular care include fear, embarrassment, financial difficulties, chaotic lifestyles, and challenges in accessing dental services.8 The disruptive lifestyle that accompanies homelessness means that oral health and healthy eating take a lower priority in day-to-day life. In addition, other lifestyle factors that are inherent in homelessness also impact on the maintenance of oral health. The Homeless Link survey reported that 36% of homeless people had taken drugs in the previous six months, two-thirds drank excessively or showed binge tendencies, 77% smoked, and 27% were deemed to be 'recovering' from an alcohol problem.9 Although the oral health needs experienced by the homeless population appear considerable, they are not necessarily complex from a clinical perspective. Often simple, straightforward dentistry is the most appropriate and effective way of addressing these needs, and Crisis at Christmas provides a unique opportunity for patients to access routine dental treatment in a safe environment. The following service review describes the provision of dental care by the CCDS over the last six years of clinical activity.

Method

Data regarding treatment provided, as well as patient feedback, were retrieved from clinical notes held for each patient that attended the dental service between 2011–2016. The numbers of dental examinations, oral hygiene instructions, scale and polishes, permanent fillings, extractions and fluoride varnish applications undertaken over the six-year period were inserted into an Excel spreadsheet.

Anonymised patient feedback questionnaires were issued after each dental treatment session and completed in the reception room located away from the clinical area. The reception staff were trained to aid patients in completing the forms where there were barriers due to language or literacy. The forms utilised a Likert-type scale to record responses. These were collected anonymously and no patient identifiable data were noted. As patient feedback collection began in 2012, the data presented includes the period 2012–2016.

Feedback was also obtained from volunteers in order to assess their opinions regarding the administration, organisation and quality of the service. It also captured their views on participating in charitable work, as well as basic demographic data including their age, gender and nationality.

Results

Patient demographic data

Each year at Crisis at Christmas, there are considerably more male than female attendees. This gender distribution is also reflected by the patients visiting the CCDS (Fig. 1). The majority of patients are aged between 22 and 60 years of age, peaking between the ages of 41 and 50 (Fig. 2). Demographic data for age and gender were collected for the 2013–2016 cohorts. The most common nationality was British which accounted for approximately 41% of those attending the service in 2016 (Fig. 3).

Patient treatment data

Over the past six years, 2,454 patient attendances have been recorded by the service. There has been a steady increase in the number receiving oral hygiene instruction as well as permanent restorations and fluoride varnish applications, while the number of extractions has changed little (Fig. 4).

Patient feedback data

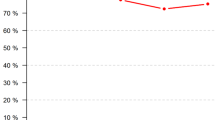

Patient feedback data have been collected since 2012. Consistently high levels of patient satisfaction of approximately 97% have been achieved across all years and those willing to recommend the service to others have also been very high at 97% (Fig. 5). Data have been collected on dental attendance since 2014 and have shown that those who do not regularly attend a dentist outside of CCDS have increased from 66% to 75% in 2016. It is not clear how many of these patients now use CCDS as their regular dentist rather than visiting other dental services either in a community or general practice setting.

Crisis at Christmas Dental Service volunteers

In 2014 the lead author began to survey the dental volunteers providing the service. The majority of respondents consistently reported that they enjoyed their time volunteering with the CCDS, most believed that they were able to make a difference by supporting the service and would volunteer again in the future (Fig. 6). The majority felt able to voice concerns to their shift leader and were satisfied with the materials and equipment provided.

Discussion

The CCDS has seen a steady increase in the number of patients attending for dental examination and treatment between 2011 and 2016. Not only has the service provided interventional dental treatment but it gives an opportunity for oral health promotional advice and fluoride varnish application to an at risk population group, 75% of whom do not routinely attend a dentist. In addition, the vast majority of responses to the treatment provided by the service were positive. There has been a drive towards implementation of preventative measures as described in Delivering Better Oral Health.10 Feedback from both patients and volunteers is essential in ensuring that the service continues to evolve within the NHS mandate, and is responsive to the needs of its end users.

The literature has consistently reported that people experiencing homelessness can have an apathetic view of their oral healthcare needs; it may only become a priority when conditions becomes acute and force them to seek immediate urgent care.11,12 Caton et al. suggest that 'a successful service needs to be informal, adapt to patient needs and accommodate chaotic lives.'8 This is also the recommendation of the Scottish oral health improvement homelessness programme, Smile4Life, suggesting that there must be a flexible three-tiered approach which involves: emergency dental services; one-off single-item treatments without a full course of treatment; and the option to receive routine dental care.9 Based on this evidence the CCDS has adapted services to be able to provide both emergency and single-item treatments without the need to complete a full course of treatment. However, the service always signposts patients to local community dental services where comprehensive dental treatment can be offered. The Scottish Government acknowledge that the 'voluntary sector also has a valuable role to play' in preventing oral diseases.7 The concept of running such a service is highly dependent on a trained and motivated workforce and the CCDS has achieved credibility that maintains a growing network of enthusiastic volunteers who repeatedly offer their services for free to support this population group every Christmas.

Conclusion

The Crisis at Christmas Dental Service has emerged as a valuable asset to the portfolio of resources accessible to vulnerable, marginalised people over the Christmas period and exposes the high dental need of the homeless population of London.

References

Butler P . Number of rough sleepers in England rises for sixth successive year. The Guardian 2017. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/jan/25/number-of-rough-sleepers-in-england-rises-for-sixth-successive-year (accessed February 2017).

Crisis. The homeless monitor. 2016. Available at http://www.crisis.org.uk/data/files/publications/Homelessness_Monitor_England_2016_FINAL_(V12).pdf (accessed February 2017).

National Statistics. Statutory homelessness: July to September quarter 2015. London: Department for communities and local government, 2015.

Hill K B, Rimmington D . Investigation of the oral health needs for homeless people in specialist units in London, Cardiff, Glasgow and Birmingham. Prim Healthcare Res Dev 2011; 12:135–144.

Daly B, Newton T, Bachelor P, Jones K . Oral health care needs and oral health-related quality of life (OHIP-14) in homeless people. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiology 2010; 38: 136–144.

Groundswell. Healthy Mouths. Executive Summary. London: Groundswell, 2017.

Smile4life. The oral health of homeless people across Scotland. Dundee: Scottish Government. Available at https://dentistry.dundee.ac.uk/sites/dentistry.dundee.ac.uk/files/smile4life_report2011.pdf (accessed February 2017).

Caton S, Greenhalgh F, Goodacre L . Evaluation of a community dental service for homeless and 'hard to reach' people. Br Dent J 2016; 220: 67–70.

Homeless Link. Homelessness and Health Research. London: Homeless Link, 2010. Available at http://www.homeless.org.uk/facts/our-research/homelessness-and-health-research (accessed November 2017).

Public Health England. Delivering better oral health. London: Public Health England, 2014.

Jago J D, Sternberg G . Oral health status of homeless men in Brisbane. Aus Dent J 1984; 29: 184–188.

De Palma P, Northareren P . The perceptions of homeless people in Stockholm concerning oral health and consequences of oral treatment: a qualitative study. Spec Care Dent 2005; 25: 289–295.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to provide their thanks to the countless volunteers who have made every Christmas service a special one, both for the patients they serve and for the others that have had the great fortune to work with them as well as Crisis for their immense support in helping the dental service to flourish. We also wish to thank Henry Schein, the BDIA and TePe for their continued generosity to the CCDS, Dental Protection Limited for providing professional indemnity for our GDC registered dental nurses to volunteer, and Community Dental Services, Kent Community Health Trust, and King's College Hospital Trust for the use of their mobile dental units over the past few years.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Doughty, J., Stagnell, S., Shah, N. et al. The Crisis at Christmas Dental Service: a review of an annual volunteer-led dental service for homeless and vulnerably housed people in London. Br Dent J 224, 43–47 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.1043

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.1043

This article is cited by

-

Models of dental care for people experiencing homelessness in the UK: a scoping review of the literature

British Dental Journal (2023)

-

Best practice models for dental care delivery for people experiencing homelessness

British Dental Journal (2023)

-

The role of mobile dental units in providing care to vulnerable communities

British Dental Journal (2023)

-

Access to healthcare for people experiencing homelessness in the UK and Ireland: a scoping review

BMC Health Services Research (2022)

-

A survey of dental services in England providing targeted care for people experiencing social exclusion: mapping and dimensions of access

British Dental Journal (2022)