Key Points

-

Reports the results of the first UK survey on the use of CAD/CAM aspects by dentists.

-

Indicates that most of the respondents did not use CAD/CAM technology in their workflow.

-

Suggests that dentists seem to agree that CAD/CAM will have a significant role to play in the future of dentistry but a significant number of CAD/CAM users felt that their training for its use was insufficient.

Abstract

Statement of the problem Digital workflows (CAD/CAM) have been introduced in dentistry during recent years. No published information exists on dentists' use and reporting of this technology.

Purpose The purpose of this survey was to identify the infiltration of CAD/CAM technology in UK dental practices and to investigate the relationship of various demographic factors to the answers regarding use or non-use of this technology.

Materials and methods One thousand and thirty-one online surveys were sent to a sample of UK dentists composing of both users and non-users of CAD/CAM. It aimed to reveal information regarding type of usage, materials, perceived benefits, barriers to access, and disadvantages of CAD/CAM dentistry. Statistical analysis was undertaken to test the influence of various demographic variables such as country of work, dentist experience, level of training and type of work (NHS or private).

Results The number of completed responses totalled 385. Most of the respondents did not use any part of a digital workflow, and the main barriers to CAD/CAM use were initial costs and a lack of perceived benefit over conventional methods. Dentists delivering mostly private work were most likely to have adopted CAD/CAM technology (P <0.001). Further training also correlated with a greater likelihood of CAD/CAM usage (P <0.001). Most users felt that the technology had led to a change in the use of dental materials, leading to increased use of, for example, zirconia and lithium disilicate. Most users were trained either by companies or self-trained, and a third felt that their training was insufficient. The majority of respondents (89%) felt that CAD/CAM had a big role to play in the future.

Conclusion Most of the respondents did not use any part of a digital workflow. However, the majority of surveyed dentists were interested in incorporating CAD/CAM into their workflow, while most believed that it will have a big role in the future. There are still some concerns from dentists about the quality of chairside CAD/CAM restorations while the costs are still in the main hugely prohibitive (especially for NHS dentistry).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The application of computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacture (CAD/CAM) technology has evolved rapidly to meet the needs of patients and simplify, as well as standardise the process of fabricating dental restorations. This change in the traditional workflow affects both clinicians and laboratory technicians.1 The demand for aesthetic and metal-free restorations has led to the development of high strength ceramics in dentistry,2,3 which may only be used in conjunction with CAD/CAM technology.4,5,6,7 The ability to provide same day chair-side restorations8,9 with these materials is also attractive to both patient and dentist. Following on from the success of CAD/CAM in the fabrication of crown and bridgework, CAD/CAM was incorporated into the production of implant abutments and frameworks in the 1990s10 and it has also shown to be reliable in constructing implant abutments, crowns and superstructures.11

Despite the aforementioned advances in technology and materials, there are currently no published studies regarding the actual use of CAD/CAM aspects by dentists. This holds true for both the UK and global markets. The only available data comes from sourcing of private market research companies. Millennium Research Group, a Canadian medical devices research provider, stated in a 2012 report that the global dental CAD/CAM market would grow strongly to reach more than $540 million by 2016 despite the economic slowdown.12 The same group updated this in 2014 to estimate total market worth of over $740 million in 2022 as the awareness of CAD/CAM increases.13 This report also estimated that the entry of new competitors would generate new market interest while intra-oral scanners would see particularly rapid adoption as dentists would increasingly use these devices to incorporate CAD/CAM technology into their surgeries rather than purchasing complete chairside systems.13 A report series by iData Research broadly came to similar conclusions and also predicted that all-ceramic restorations would approach the porcelain-fused-to-metal share by 2019.14

The aim of this survey was to identify the infiltration of CAD/CAM technology in UK dental practices and to investigate the relationship of various demographic factors to the answers regarding use or non-use of this technology.

Materials and methods

A short online survey of 20 questions (Box 1) was designed and piloted, in order to encourage participation and provide information on demographics and CAD/CAM use, which could be statistically analysed. An online rather than postal approach was decided in order to increase sample size, maximise response and decrease costs. The data being collected in a digital format would also be more readily collated and analysed.

Most questions were multiple-choice closed questions, but an option was offered for further comments at the end of relevant questions. The survey was distributed using a web-based survey tool administered by University College London, Opinio (ObjectPlanet Inc. Oslo. Norway) in May 2015. This software was able to send to all email addresses a covering letter explaining the use of the survey with a link to the survey embedded in this. The letter stated the purpose of the study and emphasised that anonymity would be preserved. Two databases were purchased from private marketing companies, List of Dentists (London UK), and Clarity Solutions (Norwich, UK), covering dentists' email contacts spread across the UK. Due to overlap between the databases, duplicates were deleted from the final list of email addresses to be used.

The survey was accessible for a 3-week period and the Opinio survey system was programmed to send out four reminders over this period to individuals who had not yet responded to the survey. Reminders were sent at different times of the day and on both weekdays and weekends to target as many dentists as possible.

The answers were collated through Opinio software as Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, USA) or SPSS (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) spreadsheets. Statistical analysis via chi-squared testing was used to examine potential associations between the survey responses and the four explanatory demographic variables: country of work, operator experience, level of training, and type of work carried out (NHS or private).

A significance level of 2.5% was used rather than a conventional 5% level to reduce the potential effects of multiple testing. This also meant that any conclusions made were as robust as possible within the limits of this project. Any P-values less than 0.025 were therefore regarded as statistically significant throughout the analyses.

Results

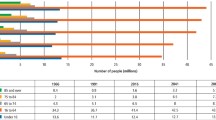

Following the exclusion of duplicates and invalid addresses, the survey was successfully distributed to 1,031 recipients. The total number of completed surveys was 385, which yielded a response rate of 19%. The majority of respondents worked in England (86%). Most had been qualified over 20 years (63%) and worked in private practice (56%). Over half of the respondents (59%) were general dental practitioners (GDPs) although a significant number of respondents (31%) had some further postgraduate training in prosthodontics or restorative dentistry. The survey, along with the results, is depicted in Box 1.

Most answers did not appear to have any significant statistical association when tested against the above demographics, but significant associations will be highlighted in the following section:

The majority of respondents (55.6%) did not use any component of CAD/CAM. The main barrier to CAD/CAM use was high cost, and GDPs were significantly more likely to quote this reason compared to dentists with restorative postgraduate degrees or specialists (P <0.001). The second most common reason reported for not using CAD/CAM was a lack of perceived advantages over conventional production methods, and this was highlighted more by dentists with further restorative postgraduate training and specialist prosthodontists (P = 0.009). Among the non-users, younger dentists were significantly more likely to be interested in incorporating CAD/CAM into their future workflow (P = 0.011). Conversely, dentists who had been qualified for more than 20 years were more likely to have answered that they were not technologically aware as a reason for not using CAD/CAM, but this was not statistically significant at the 2.5% level (P = 0.043).

From the respondents who used some aspect of CAD/CAM in their workflow, over 80% had started in the last 10 years. Further postgraduate training correlated with a greater likelihood of CAD/CAM usage (P = 0.001) while private dentists were also significantly more likely to use CAD/CAM (P <0.001). Most dentists reported adopting CAD/CAM in the hope of improving quality, and in order to use new materials that were not amenable to conventional production methods. Most CAD/CAM use revolved around the restoration of teeth or implants. However, there were other interesting non-restorative uses of CAD/CAM mentioned in the survey responses; these included use in orthodontics, use in order to reduce the storage of stone casts, and use in research and education.

A third of CAD/CAM users in the survey used a full chairside CAD/CAM system, but these were identified mostly as GDPs (P = 0.026) who were therefore more likely to use materials such as composite and lithium disilicate. Interestingly, no specialist prosthodontists used the chairside aspect of CAD/CAM and they were more likely to use only the CAM component in conjunction with metals through their dental technicians (P <0.022). Uses by specialists responding to the survey also included guided implant placement with CAD/CAM surgical stents and implant restorations – notably for metal frameworks and titanium milled bars.

Users of CAD/CAM were fairly evenly split when asked whether the availability of CAD/CAM affected their clinical decision-making. There were a number of common themes to the comments made on this theme; firstly, those who used full chairside CAD/CAM to restore teeth felt that they could prepare teeth more conservatively and the use of inlays, onlays, partial crowns and adhesive techniques were mentioned as reasons for this. Most of these users (71.4%) also felt that the technology had led to a change in their use of dental materials, leading to increased use of lithium disilicate and zirconia. Users of chairside CAD/CAM also commented on the time saving for both the dentist and patient. A third of CAD/CAM users felt that their training was insufficient. Regarding the possible shortfalls of CAD/CAM restorations, almost half of the users reported no issues, but 19% highlighted aesthetics as a weak point.

The majority (89%) of survey respondents felt that CAD/CAM had a big role to play in the future of dentistry. Private dentists were more likely than to NHS dentists to feel that it would have a big impact (P = 0.011), and the same held true for dentists with further restorative postgraduate training or specialists when compared to GDPs (P = 0.018).

A number of respondents took the opportunity to offer some comments at the end of the survey. The following is a small selection of some thought-provoking comments made:

-

'Laboratories need to embrace this technology. If they fail to understand that dentists are now able to produce high quality restorations in-house and work with the systems to provide more of the high-end work then they are going to fail in the long-run.'

-

'Unfortunately, it may result in some of the dental profession being made redundant and de-skilling may occur. The traditional dental team set-up may change considerably.'

-

'Too expensive to buy the machinery, therefore charges too high for patients and you feel obliged to use it.'

-

'CAD/CAM has a reputation based on some of the older restorations made which were let down by things like composite cement. It is a shame the image has been tarnished.'

-

'More university/independent courses (evidence based) and CPD on CAD/CAM would be helpful to replace the present self-taught or product-led training.'

-

'Constant upgrading and depreciation of equipment – today's latest intra-oral scanner might be out of date tomorrow and obsolete in a few years' time.'

Discussion

1) Survey design

An online rather than postal method of delivery was used for the survey even though lower response rates have been recorded with online surveys.15,16 This allowed for a larger sample size and decreased the costs of this project. However, based on the number of invalid addresses, the private databases were not as accurate as would be expected. The response rate of 19% found in this project was slightly lower, compared to other published surveys of dental professionals.17,18 A number of factors could have influenced the response rate: unused email addresses, or simply a lack of interest in completing the survey or in the subject matter. It would also be reasonable to assume that this survey would not be applicable to a number of dentists included in the database, for example, paediatric or special care dentists.

There are a number of methods of potentially improving response rate but it is unclear how much of an impact this would have. These include providing incentives or prize draws for respondents, sending more reminders, or extending the duration of the survey. An attempt could was made at recruiting the support of a dental organisation, such as the British Dental Association or the Faculty of General Dental Practitioners, but this was not possible within the bounds of this particularly study.

Although the response rate was not very high, the number of responses, the adjustment of the level of significance, and the fact that this was the first attempt of its kind, permit some meaningful conclusions, within the limitations of the external validity to the UK dentist population.

2) Demographics

The majority of dentists who completed the survey came from England, and the geographic distribution correlated well with the actual percentages found in the GDC's 'Facts and figures'.19 The vast majority of respondents were experienced practitioners who were qualified for over 11 years and performed predominantly private work. This might suggest that more experienced individuals, delivering mostly private dentistry were more likely to have filled out the survey but this might also be due to a skewed initial data set.

3) Responses from CAD/CAM users

Less than half of respondents used CAD/CAM technology as part of their workflow and nearly half of these dentists had only started using CAD/CAM in the last 5 years. This result highlights the fact that CAD/CAM is still a relatively new development in the dental world for most dentists. This is the first time that a statistic on CAD/CAM use by dentists has been reported in a peer-reviewed study, and the first of its kind for the UK. The lack of similar studies does not allow for meaningful comparisons of the results of the current study with the existing literature.

Dentists who had further restorative postgraduate training were significantly more likely to use CAD/CAM as part of their workflow. However, specialists were more likely to use the CAM aspect only, whereas GDPs were more likely to utilise a full chairside use. There are several potential explanations for this finding. Specialists tend to do more complex cases where occlusal control and choice of dental materials are both of paramount importance. Although some chairside CAD/CAM systems incorporate the use of a 'virtual articulator', there is still a lack of quantitative data with regards to the accuracy of occlusal contacts,20 and this technology is still in progress.21 In terms of dental materials, specialists may be more likely to require the use of precious alloys, especially in more complex cases, which are not amenable to CAD/CAM fabrication procedures. Gold crowns require the least tooth reduction, can be adhesively cemented to enamel,22 and remain the 'gold' standard in terms of longevity.23 Another explanation for specialist prosthodontists not using a chairside CAD/CAM system in this survey could lie in the fact that the majority (17 out of 22) had been qualified for over 20 years. It is possible these dentists were more likely to have used conventional methods for a longer period and had not seen the need to change.

Most CAD/CAM users had some form of training by companies or were self-taught but a significant percentage (33%) felt that this training was insufficient. This finding clearly highlights a gap in dental education and continuing professional development (CPD) courses. It may be time for universities to offer formal evidence-based teaching of CAD/CAM technology in CPD courses.

A significant number of CAD/CAM users reported that the technology had affected their clinical decision-making and choice of materials, mainly increasing the use of lithium disilicate and zirconia. It was interesting to observe that the respondents related CAD/CAM use to more conservative tooth preparations and adhesive dentistry, whereas this technology is not a pre-requisite for such clinical approaches. This may be the result of company-led training. From a material point of view, zirconia can only be processed through CAD/CAM technology. However, its clinical use is not without technical problems and long-term survival data is lacking.24,25 One respondent mentioned the potential for over-use of a chairside CAD/CAM system and materials to make up for the expense of the equipment itself. This comment highlights the possibility that dentists may use materials they would not otherwise have chosen to use if CAD/CAM had not been available.

Users of chairside CAD/CAM also commented on the time saved as there was no lab-turnaround time involved, and restorations could be fitted on the same day without the need for provisionalisation. This is in agreement with the literature26,27 showing that digital production methods may be more cost/time effective. Those who used CAD/CAM as part of their implant workflow felt that it allowed for accurate 3D planning and could possibly enable flapless implant placement. This aspect of CAD/CAM has been increasingly well documented and developed through the years.28,29,30

An interesting finding of the survey was that the aesthetic quality was highlighted as the major shortcoming of CAD/CAM restorations. Although there are no recently published studies on this issue,31 it is noteworthy that the industry has introduced polychromatic blocks of materials for CAD/CAM use during the last years, possibly in an attempt to improve aesthetics of monolithic restorations.

4) Responses from non-CAD/CAM users

The majority of respondents to the survey did not currently use CAD/CAM in their workflow. By far the most common reason for not using CAD/CAM was high initial costs, especially for GDPs. The second most common reason was the lack of perceived advantages over conventional fabrication routes, referred to more by dentists with further restorative postgraduate training and specialist prosthodontics. Indeed, with the exception of possible time and cost effectiveness,26,27 the current literature11,32,33,34 has shown that digital workflows can produce restorations which perform equally well compared to those fabricated through conventional workflows. However, more than half of non-users responded positively regarding the future incorporation of digital workflows, particularly younger dentists as would be expected.

The various interesting comments made by respondents clearly highlighted initial costs as the major obstacle for the incorporation of digital workflows, particularly in NHS settings. Based on the potential time/cost benefits offered by technology, the NHS should consider a cost/benefit analysis in future planning. This obstacle was further highlighted by the fact that, although the vast majority of respondents (89%) felt that CAD/CAM had a big future in dentistry, dentists who undertook predominantly private work were significantly more likely to answer positive.

Conclusion

Within the limits of this study, the following conclusions could be drawn:

-

Most of the respondents did not use CAD/CAM technology in their workflow. High initial costs and the lack of perceived advantages over conventional restorations were the main reasons reported for this

-

The vast majority of dentists seem to agree that CAD/CAM will have a significant role to play in the future of dentistry

-

A significant number of CAD/CAM users felt that their training for its use was insufficient.

References

Miyazaki T, Hotta Y, Kunii J, Kuriyama S, Tamaki Y . A review of dental CAD/CAM: current status and future perspectives from 20 years of experience. Dent Mater J 2009; 28: 44–56.

Raigrodski A J, Chiche G J . The safety and efficacy of anterior ceramic fixed partial dentures: A review of the literature. J Prosthet Dent 2001; 86: 520–525.

Raigrodski A J . Contemporary materials and technologies for all-ceramic fixed partial dentures: A review of the literature. J Prosthet Dent 2004; 92: 557–562.

Perng-Ru L . A Panorama of Dental CAD/CAM Restorative Systems. Compendium 2008; 29: 482–493.

Christensen G . Clinical status of eleven CAD/CAM materials after one to twelve years of service. In Mormann W H (ed) State of the art of CAD/ CAM restorations: 20 years of CEREC. Surrey: Quintessence Publishing, 2006.

Miyazaki T, Nakamura T, Matsumura H, Ban S, Kobayashi T . Current status of zirconia restoration. J Prosthodont Res. 2013; 57: 236–261.

Takaba M, Tanaka S, Ishiura Y, Baba K . Implant-supported fixed dental prostheses with CAD/CAM-fabricated porcelain crown and zirconia-based framework. J Prosthodont 2013; 22: 402–407.

Otto T, Dent M . Computer-aided direct ceramic restorations: A 10-year prospective clinical study of cerec CAD/CAM inlays and onlays. Int J Prosthodont 2002; 15: 122–129.

Fasbinder D J . Using Digital Technology to Enhance Restorative Dentisty. Compendium 2012; 33: 666–677.

Priest G . Virtual-designed and computer-milled implant abutments. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005; 63: 22–32.

Kapos T, Evans C . CAD/CAM technology for implant abutments, crowns, and superstructures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2014; 29: 117–136.

Millenium Research Group. Market analysts predict growth in 3D printing and dental CAD/CAM. 2012. Online information available at: http://www.dentalproductsreport.com/lab/article/market-analysts-predict-growth-3d-printing-and-dental-cadcam (accessed Nov 2016)

Millenium Research Group. Global Markets for Dental CAD/CAM systems. 2014. Online information available at: http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/the-global-dental-cadcam-system-market-will-see-strong-growth-to-reach-a-value-of-over-760-million-in-2022-264396261.html (accessed Nov 2016)

iData Research. European Markets for Dental Prosthetics and CAD/CAM devices. 2013. Online information available at: https://www.idataresearch.com/product/european-markets-for-dental-prosthetics-and-cadcam-devices-2013-medsuite/ (accessed Nov 2016)

Cook C, Heath F, Thompson R L . A meta-analysis of response rates in webor internet-based surveys. Educ Psychol Meas 2000; 60: 821–836.

Nulty D D . The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: what can be done? Assess Eval High Educ 2008; 33: 301–314.

Rath C, Sharpling B, Millar B J . Survey of the provision of crowns by dentists in Ireland. J Irish Dent Assoc 2010; 56: 178–185.

Berry J, Nesbit M, Saberi S, Petridis H . Communication methods and production techniques in fixed prosthesis fabrication: a UK based survey. Part 1: Communication methods. Br Dent J 2014; 217: E12.

General Dental Council. GDC registrant report October 2015. 2015. Online information available at http://www.gdc-uk.org/Newsandpublications/factsandfigures/Documents/Facts%20and%20Figures%20from%20the%20GDC%20register%20October%202015.pdf (accessed October 2016).

Fasbinder D J, Poticny D J . Accuracy of occlusal contacts for crowns with chairside CAD/CAM techniques. Int J Comput Dent 2010; 13: 303–316.

Sun Y, Li H, Yuan F, Zhao Y, Lu P, Wang Y et al. Evaluation of the accuracy of three-dimensional reconstruction of edentulous model jaw relation based on dental articulator positioning. Conference paper: Ieee International Conference on Imaging Systems and Techniques 2013; 10.1109/IST.2013.6729739.

Jamous I, Sidhu S, Walls A . An evaluation of the performance of cast gold bonded restorations in clinical practice, a retrospective study. J Dent 2007; 35: 130–136.

Manhart J, Chen H, Hamm G, Hickel R . Buonocore Memorial Lecture. Review of the clinical survival of direct and indirect restorations in posterior teeth of the permanent dentition. Oper Dent 2004; 29: 481–508.

Pjetursson B E, Sailer I, Malzarov N A, Zwahlen M, Thoma D S . All-ceramic or metal-ceramic tooth-supported fixed dental prostheses (FDPs)? A systematic review of the survival and complication rates. Part II: Multiple-unit FDPs. Dent Mater 2015; 31: 624–639.

Sailer I, Makarov N A, Thoma D S, Zwahlen M, Pjetursson B E . All-ceramic or metal-ceramic tooth-supported fixed dental prostheses (FDPs)? A systematic review of the survival and complication rates. Part I: single crowns (SCs). Dent Mater 2015; 31: 603–623.

Patzelt S B M, Lamprinos C, Stampf S, Att W . The time efficiency of intraoral scanners An in vitro comparative study. J Am Dent Assoc 2014; 145: 542–551.

Joda T, Brägger U . Digital vs. conventional implant prosthetic workflows: a cost/time analysis. Clin Oral Implant Res 2014; 26: 1430–1435.

Sarment D P, Sukovic P, Clinthorne N . Accuracy of implant placement with a stereolithographic surgical guide. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2003; 18: 571–577.

Ozan O, Turkyilmaz I, Ersoy A E, McGlumphy E A, Rosenstiel S F . Clinical accuracy of 3 different types of computed tomography-derived stereolithographic surgical guides in implant placement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009; 67: 394–401.

Marchack C B . CAD/CAM-guided implant surgery and fabrication of an immediately loaded prosthesis for a partially edentulous patient. J Prosthet Dent 2007; 97: 389–394.

Herrguth M, Wichmann M, Reich S . The aesthetics of all-ceramic veneered and monolithic CAD/CAM crowns. J Oral Rehabil 2005; 32: 747–752.

Güth JF, Keul C, Stimmelmayr M, Beuer F, Edelhoff D . Accuracy of digital models obtained by direct and indirect data capturing. Clin Oral Investig 2013; 17: 1201–1208.

Seelbach P, Brueckel C, Wöstmann B . Accuracy of digital and conventional impression techniques and workflow. Clin Oral Investig 2013; 17: 1759–1764.

Fasbinder D J . Clinical performance of chairside CAD/CAM restorations. J Am Dent Assoc 2006; 137 Suppl: 22S–31S.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge UCL for funding this project and David Boniface for his help in the statistical analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with respect to the submitted work.

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tran, D., Nesbit, M. & Petridis, H. Survey of UK dentists regarding the use of CAD/CAM technology. Br Dent J 221, 639–644 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.862

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.862

This article is cited by

-

Knowledge, awareness, and perception of digital dentistry among Egyptian dentists: a cross-sectional study

BMC Oral Health (2023)

-

Perceptions of orthodontic residents toward the implementation of dental technologies in postgraduate curriculum

BMC Oral Health (2023)

-

The precision of two alternative indirect workflows for digital model production: an illusion or a possibility?

Clinical Oral Investigations (2023)

-

Making an IMPACTT: A framework for developing a dentist's ability to provide comprehensive dental care

BDJ In Practice (2022)

-

Digital implant planning and guided implant surgery – workflow and reliability

British Dental Journal (2019)