Key Points

-

Highlights that referrals to a specialist facial pain service come from both dental and medical practitioners.

-

Suggests a suitable pain history enables a differential diagnosis to be made resulting in correct triaging to appropriately qualified staff.

-

Notes that mental health issues are often omitted in referrals and yet they constitute significant co-morbidity in non-dental facial pain conditions.

Abstract

Aim To assess the quality of referral letters to a facial pain service and highlight the key requirements of such letters.

Method The source of all referral letters to the service for five years was established. For one year the information provided in 94 referrals was assessed. Using a predetermined checklist of essential information the referral letters were compared to these set criteria.

Results The service received 7,001 referrals and, on average, general dental practitioners (GDPs) referred 303 more patients per year than general medical practitioners (GMPs). Seventy-one percent of all referrals were from primary care practitioners, the rest were from specialists. Over 70% of GMP and 52% of GDP letters included a past medical history, with GMPs more likely to suggest a possible diagnosis and include previous secondary care referrals. The mean score for GMP referrals compared to the standard proforma (maximum of 12) was 5.6 and for GDP referrals 5.0. A relevant drug history was included by 75.6% GMP compared to 38.7% of GDPs. GMPs were more likely to include any relevant mental health history.

Conclusions The overall quality of referral letters is low which makes it difficult for the specialists to provide robust treatment plans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic facial pain is a long-term condition that is often extremely complex, and frequently requires input from the secondary care sector. Patients will frequently access both their GDP and GMP in their attempts to find a cure.1 It is therefore essential that all service providers communicate with each other effectively. However, it has been shown that this is often not the case, particularly due to the multidisciplinary nature of this condition.2,3

The initial main form of communication is the referral letter, which therefore needs to be of good quality. A medical history including past and present medications helps prevent polypharmacy and encourages safer prescribing, in addition to assisting the specialist in formulating a management plan without additional 'time-wasting' correspondence with the GDP or GMP. Referral letters continue to be inadequate, and even contain inaccurate information.4 One study found that only 58% of referral letters gave an accurate list of medications and drug doses used by their patients.5 Furthermore it has been shown that medical information provided by GDPs is of inferior quality compared to GMPs.6 GDPs referring to orthodontics make no mention of a medical history in 80% of instances7 and only 60% of letters requesting sedation for extractions contained sufficient medical history.8

Patients with chronic facial pain have considerable co-morbidities that require complex interventions.9 GDPs refer patients with non-dental facial pain and so, their subsequent management will often be shared between the specialist centres and the GMP, as GDPs are very restricted in the medications they can prescribe. On the other hand, GMPs referring patients to a facial pain service will probably have been unable to eliminate a dental cause for the pain, and in some instances should have suggested patients first see their GDPs.

This study aimed to determine who initially refers patients to a national facial pain service, assess the quality of referral letters with respect to the ability of hospital specialists to triage patients to appropriate pathways, and initiate a shared treatment plan, which includes prescribing. It aims to highlight the key contents of referral letters to a facial pain service.

Methods

The study took place in a London based secondary and tertiary referral centre specialising in the treatment of chronic, complex non-dental facial pain that does not include headaches or migraines. The service was significantly re-vamped in 2007 and is led by an oral physician/pain medicine specialist, together with a range of specialists: consultants in oral medicine, oral surgery, liaison psychiatry, clinical psychology, neurology, neurosurgery, and complementary and alternative medicine. Further support is provided by physiotherapists, clinical nurse specialists, and dental nurses, who are all supported by a service manager, in addition to dedicated secretaries. Annually the service sees 700 new patients and over 1,500 follow up patients from all parts of the UK.

All referral letters to the facial pain service are triaged by a senior clinician who maintains a database recording the source of the referral. If the primary care letter includes correspondence from a secondary care provider, or this is mentioned in the letter, then a separate note is made that the primary care referral is essentially a secondary or tertiary care referral. Based on all the details in the referral letter, patients are then allocated to varying clinicians dependant on the skills required. If there is insufficient detail provided, referrals are sent back to the referrer for clarifications. If medical histories are missing, GMPs are contacted irrespective of whether they referred the patient.

For the review of the source of referrals, all referral letters were considered from April 2007 to October 2012. Over a one year period all 94 referral letters that were received from primary care sources (50 GDP and 44 GMP) were reviewed for content. Each clinician keeps a database of all patients allocated to them, which includes the diagnosis. The commonest condition that was referred was temporomandibular disorders (TMD).

Outcome measures

A checklist of essential information required when referring a patient with chronic facial pain was developed based on standards set by several research publications, including Ryle10 and Zakrzewska,11 and the referral proforma used by UCLH available online (http://www.uclh.nhs.uk/OurServices/ServiceA-Z/EDH/MAXMED/FPAIN/Pages/refer.aspx). A gold standard was devised to which referral letters were compared. For the 12 items a score of 0 indicated not present/inadequate, 1 was present/adequate so the maximum score was 12. These criteria and further details are shown in Table 1.

Relevant past medical histories mentioned within the referral letter were noted and compared to the corresponding medical histories taken by the medical team in the service. Where there was no medical history it was classified as 'No', whereas where a relevant medical history was provided and was adequate, it was termed a 'Yes'. Where a medical history was present but not provided in the referral letter, it was classified as 'Inadequate'. Fourteen items of the medical history were considered important.

Power of the study

Previous reviews of papers dealing with referral letters used 100 letters.12,13 In order to obtain an equal number of simple and complex cases for analysis, letters were taken in an approximately equal proportion across all three databases (patients seen by the consultant, specialist registrar and foundation dentist). In total, 94 referral letters were obtained, 50 of which were GDP letters and 44 GMP referrals.

Results

Source of referrals

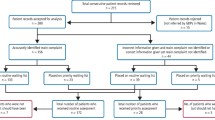

Over the five year period, a total of 7,001 referrals were received, on average, over 1,000 referrals were made to the service annually. Of those, 15% to 29% (an average of 299 referrals) were rejected each year as they did not conform to the criteria for referral, did not require secondary care input, or provided inadequate information. Of the rejected referrals, the highest proportion came from the GDPs, making up 84% of the total referrals not accepted by the service.

Of those patients accepted, between 25–30% (average of 241 referrals) either do not attend (DNA) or do not make an appointment when invited to do so. In the year 2009 to 2010, referrals came from 80 primary care trusts (at the time there were 95 PCTs), with one local PCT referring 90 patients, with other more local PCTs referring between 30 to 60, and overall 31 PCTs referred more than 10 new patients in a year.

More GDPs refer into the service than GMPs as shown in Figure 1, and this proportion is stable over the years. On average GDPs refer 303 more patients per year compared to GMPs (Fig. 1).

Twenty nine percent of accepted referrals are referred directly from specialists. However, on analysing the referral letters from GDPs and GMPs, it is evident that on average 44.3% of letters per year are actually already tertiary referrals as they either mention or provide letters from secondary care providers. This is an additional number of 175 referrals per year that are actually tertiary referrals.

Adequacy of referral letters

A total of 94 referral letters from the period of 2013 to 2014 was collected for analysis. Of these, 50 were GDP referrals and 44 from GMPs. The foundation dentists are not often allocated patients referred by GMPs. They saw 17 of the patients referred by the GDP, and 11 from the GMP. The specialist registrar saw 17 patients each from the two referrers, and the consultant 16.

The breakdown items of orofacial pain included in the referral letters are shown in Table 1. Characteristics of the pain mentioned by the practitioners are relatively equal. The most frequent category not included in GDP and GMP referral letters were social and family history, being present in only 12% and 22.7% of letters respectively. Over 70% of GMP letters and 52% of GDP letters included some past medical history. GMPs were much more likely to put forward a possible diagnosis and include information about secondary care referrals.

The mean score for GMP referrals out of 12 was 5.6 (standard deviation 2.6, range 1-12). Mean score for GDP referrals was 5.0 (standard deviation 2.2, range 1-9).

UCLH website has a recommended proforma, and this was used by ten GDPs and six GMPs, with average scores of 5.8 and 6 respectively.

Table 2 shows the medical history completeness in the referral letters. There was no relevant medical history in two patients, and these have been adjusted for in the table. Overall, GMPs letters were more complete.

Table 3 details contents of referral letters from the GMP, and Table 4 shows GDP contents of referral letters.

It was found that 41 patients referred from the GMP contained a relevant drug history. Of these, 75.6% of letters included this information but 24.4% did not. In comparison, only 38.7% of the 31 GDP referral letters included the relevant drug history, with 61.3% of the letters not giving it any mention at all. One referral quoted no medical history, and yet the patient had multiple medical problems and was on 12 prescribed medications.

Out of the 94 referrals, mental health history was present in 39 patients, but only 18 letters gave any mention of this. The GMP was more likely (66.7%) than the GDP (28.6%) to mention a mental health history. For example, one GDP made no mention that the patient had bulimia and Asperger's syndrome, as well as admission for an overdose.

Discussion

Referral letters to a secondary/tertiary facial pain service require specific information which may not be required for other referrals to specialist dental services. Mental health problems are often not mentioned especially by GDPs and yet were present in 41% of the patients in this cohort. Mental health problems are a significant co-morbidity for this group of patients. An orofacial pain clinic in Japan found half their patients (60) had mental health disorders.14

Although overall there was no significant improvement in the referral letter score with the proforma, and there was no significant difference in the quality of referrals from GMPs and GDPs when it was used, this could have been due to small sample size. Djemal et al.13 and Shaffie and Cheng15 both found referrals from GDPs improved when using a proforma. But on the other hand Denith et al.,8 although finding medical histories improved with use of proformas, found less general information was provided – something noted in this study. Some practitioners include a cover letter providing some of this data. A Cochrane review looking at interventions to improve referrals found structured proformas could help, but local educational interventions were equally important.16 Kripke17 suggests that guidelines are also useful and that the education should be delivered by specialist consultants. This needs re-enforcing as fall off is noticed after two years.18

A detailed past medical history and possible diagnosis is indispensable in enabling appropriate triaging to occur, in addition to allowing specialists to manage the patient in a holistic manner along appropriate care-pathways. A good referral letter helps cut down on the time needed to collect data, and allows specialists more time on information giving and management decisions. Inadequacy of GDP referrals could in part be due to general perception among the public that GDPs do not need to know their patients' medical history, and so some patients will not disclose information which may be of relevance.19

Medications cannot be prescribed without an adequate medical and drug history. Prescribers must check that lists provided by GMPs are accurate, as a study has shown that 37% of lists may be inaccurate and dosages were not accurate in 16% of referrals.5 It is also very helpful if details of previous drugs used for the condition are provided, as it can be determined whether adequate doses have been used for a sufficient length of time and how well tolerated they were. Any medications prescribed in the facial pain service will need to be continued and currently these can only be prescribed by GMPs.

GDPs are very effective at ruling out dental causes. Only 8% of referrals to the service are determined to have a primary dental cause. However, GDPs need to work more closely with GMPs to ensure that they have a full medical history.

Conclusions

Our study shows that the overall quality of the referral letter from primary care practitioners needs to be improved. Currently the average GDP and GMP referral letter does not include sufficient details to enable accurate triaging and treatment planning. Specialists need to put forward a comprehensive treatment plan, prescribe appropriate medication safely and share care with a primary care practitioner. To do this effectively it is essential that referral letters contain comprehensive details of the medical history which includes the drug and mental health history.

References

Feinmann C, Peatfield R . Orofacial neuralgia. Diagnosis and treatment guidelines. Drugs 1993; 46: 263–268.

Madland G, Newton-John T, Feinmann C . Chronic idiopathic orofacial pain: I: What is the evidence base? Br Dent J 2001; 191: 22–24.

Beecroft E V, Durham J, Thomson P . Retrospective examination of the healthcare 'journey' of chronic orofacial pain patients referred to oral and maxillofacial surgery. Br Dent J 2013; 214: E12.

Garasen H, Johnsen R . The quality of communication about older patients between hospital physicians and general practitioners: a panel study assessment. BMC Health Serv Res 2007; 7: 133.

Carney SL . Medication accuracy and general practitioner referral letters. Intern Med J 2006; 36: 132–134.

DeAngelis A F, Chambers I G, Hall G M . The accuracy of medical history information in referral letters. Aust Dent J 2010; 55: 188–192.

Izadi M, Gill D S, Naini FB . A study to assess the quality of information in referral letters to the orthodontic department at Kingston Hospital, Surrey. Prim Dent Care 2010; 17: 73–77.

Dentith G E, Wilson K E, Dorman M, Girdler N M . An audit of patient referrals to the sedation department of Newcastle Dental Hospital. Prim Dent Care 2010; 17: 85–91.

Zakrzewska JM . Multi-dimensionality of chronic pain of the oral cavity and face. J Headache Pain 2013; 14: 37.

Ryle JA . The natural history of disease. London: Oxford University Press, 1936.

Zakrzewska JM . Referral letters-how to improve them. Br Dent J 1995; 178: 180–182.

Moloney J, Stassen L F . An audit of the quality of referral letters received by the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Dublin Dental School and Hospital. J Ir Dent Assoc 2010; 56: 221–223.

Djemal S, Chia M, Ubaya-Narayange T . Quality improvement of referrals to a department of restorative dentistry following the use of a referral proforma by referring dental practitioners. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 85–88.

Ikawa M, Yamada K . Mental disorders diagnosed in half of outpatients in orofacial pain clinic. Psychosomatics 2006; 47: 179–180.

Shaffie N, Cheng L . Improving the quality of oral surgery referrals. Br Dent J 2012; 213: 411–413.

Akbari A, Mayhew A, Al-Alawi M A et al. Interventions to improve outpatient referrals from primary care to secondary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; 4: CD005471.

Kripke C . Improving outpatient referrals to secondary care. Am Fam Physician 2006; 73: 803–804.

Hill V A, Wong E, Hart C J . General practitioner referral guidelines for dermatology: do they improve the quality of referrals? Clin Exp Dermatol 2000; 25: 371–376.

Edwards J, Palmer G, Osbourne N, Scambler S . Why individuals with HIV or diabetes do not disclose their medical history to the dentist: a qualitative analysis. Br Dent J 2013; 215: E10.

Acknowledgements

JZ undertook this work at UCL/UCLHT, who received a proportion of funding from the Department of Health's NIHR Biomedical Research Centre funding. Academics organised the placement of the students.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lang, M., Selvadurai, T. & Zakrzewska, J. Referrals to a facial pain service. Br Dent J 220, 345–348 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.262

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.262