Key Points

-

Suggests previous halitosis classification systems omit some aetiologies, and their diagnoses hinged on single occasion halitometric and organoleptic findings, which are unreliable.

-

Proposes halitosis diagnosis should focus more on the declarations of the patient and his/her social environment.

-

Suggests the new classification completely covers all possible aetiologies of halitosis.

Abstract

Background There is no universally accepted, precise definition, nor standardisation in terminology and classification of halitosis.

Objective To propose a new definition, free from subjective descriptions (faecal, fish odour, etc), one-time sulphide detector readings and organoleptic estimation of odour levels, and excludes temporary exogenous odours (for example, from dietary sources). Some terms previously used in the literature are revised.

Results A new aetiologic classification is proposed, dividing pathologic halitosis into Type 1 (oral), Type 2 (airway), Type 3 (gastroesophageal), Type 4 (blood-borne) and Type 5 (subjective). In reality, any halitosis complaint is potentially the sum of these types in any combination, superimposed on the Type 0 (physiologic odour) present in health.

Conclusion This system allows for multiple diagnoses in the same patient, reflecting the multifactorial nature of the complaint. It represents the most accurate model to understand halitosis and forms an efficient and logical basis for clinical management of the complaint.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature review

Previous definitions

Halitosis is receiving increasing scientific interest, but still no accepted definition exists. In the literature, definitions include: 'the subjective perception after smelling someone's breath, if unpleasant',1 'noticeably unpleasant odours exhaled in breathing',2 'an oral health condition characterised by unpleasant odours emanating consistently from oral cavity',3 'general term to describe any disagreeable odour of breath, regardless of its origin',4 and 'an unpleasant odour emanating from oral cavity.'5

Many definitions are inadequate, ignoring the potential emanation of odours via the mouth and nose from the respiratory and gastroesophageal tracts, transfer of volatiles from blood to breath during alveolar gas exchange, and also self-perception of halitosis by the patient. To varying degrees the breath always has odorant volatiles, originating orally or elsewhere. None set a clear boundary between normal, physiologic breath odour and, pathologic halitosis. Negative identification of an odour requires qualification. Who determines this? The patient, the patient's social environment, or the clinician by sulphide detectors (halitometers)? Some refer to exogenous odorants (for example, garlic) as halitosis, yet this is not pathologic. To distinguish normality from disease, a more precise definition and classification is needed.

This paper reviews previous attempts at classification and definition of halitosis and forwards a new scheme. The diagnosis and treatment of halitosis according to this scheme are discussed in a separate publication.

Previous classifications

Miyazaki et al.6 suggest genuine halitosis, pseudo-halitosis and halitophobia (Fig. 1). Genuine halitosis is divided into physiological or pathological, then the latter is split into oral and extra-oral. This was adapted to North American society with regards to halitophobia, and appeared in publications a decade ago.7,8,9 This classification is inflexible since multiple diagnoses for one patient are not enabled. The broad category 'extra-oral, pathologic halitosis' does not aid referral choice or help the receiving clinician, and is also poor for researchers who need to precisely classify extra-oral halitosis according to aetiology. 'Morning breath' is not placed in the oral category, despite manifesting orally. Inappropriately, two out of three categories (pseudo-halitosis and halitophobia) have psychopathologic connotations and they are excluded from pathologic halitosis. Subjective halitosis can be caused by psychologic or neurologic factors, which are technically extra-oral processes, yet 'extra-oral halitosis' is again excluded from pathologic halitosis. After treatment, whether for genuine halitosis or pseudo-halitosis, if the patients continue to believe they have halitosis, reclassification to halitophobia occurs. This categorises cases according to treatment outcome, as halitophobia is diagnosed following a failed treatment. This scheme claims to provide treatment needs, but how can these be determined beforehand if they depend on results of treatment? Pseudo-halitosis is misleading when considered alongside other medical terms, for example, pseudo-Cushing's syndrome, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, pseudo-lymphoma or pseudo-Kaposi's sarcoma. These exist as physical entities that masquerade as their namesake. Pseudo-halitosis implies a genuine, physical condition mistaken for non-existent halitosis. Similarly, halitophobia suggests an irrational fear, but instead refers to where the patients believe their treatment unsuccessful.

Miyazaki et al. 1999 is generally the most widely used, but neither is universally accepted5

Tangerman and Winkel suggest intra- and extra-oral halitosis, the latter then divided into non-blood-borne and blood-borne.10 An earlier publication divides extra-oral halitosis into blood-borne, upper respiratory tract and lower respiratory tract.11 They list four aetiologic mechanisms of blood-borne halitosis: systemic diseases, metabolic disorders, food and medications.10 These authors use 'pseudo-halitosis/halitophobia' to describe no measurable halitosis, while retaining their own classification for measurable halitosis.12 In reality, this classification focuses on oral and blood-borne halitosis, with insufficient categorisation of physiologic, sinonasal, laryngopharyngeal, gastroesophageal or psychologic causes. The significance of blood-borne halitosis relative to other extra-oral mechanisms is unclear and a broad division into blood-borne and non-blood-borne may be inappropriate. Again, this system does not allow for multiple diagnoses, making accurate categorisation of some cases difficult, and there is no distinction between pathologic and physiologic halitosis.

Motta et al. suggest primary halitosis ('respiration exhaled by the lungs'), and secondary halitosis ('originates in mouth or upper airways').13 It is unclear if primary halitosis refers to blood-borne halitosis, odour from the lower respiratory tract itself, or both. This is seldom used, perhaps because the clinical utility is limited by not addressing subjective halitosis or gastroesophageal halitosis.

Previous terminology

In some cases, odour is not detected organoleptically and volatile sulphur compound (VSC) levels are normal. There is no local or systemic condition and no reliable, third party confidants confirming the complaint. This scenario is generally ascribed to psychologic factors, termed imaginary halitosis,14 delusional halitosis,15 pseudo-halitosis,7 non-genuine halitosis,16,17 chronic olfactory paranoid syndrome,18 anthropophobia (taijin kyofusho),19 halitophobia,20 olfactory reference syndrome (ORS),21,22 and social anxiety disorder.23 These terms may easily cause confusion.

The term psychosomatic halitosis is incorrectly used when referring to subjective halitosis complaints. Psychosomatic disorders are disorders in which psychologic factors play a significant role and there are physical symptoms that are detectable clinically. However, the term psychosomatic halitosis is used to describe an odour is that is clinically non-existent.

Terms that refer to odour character promote confusion for clinicians and patients, for example sulphurous/faecal, fruity, and ammoniacal/urine-like; respectively attributed to VSC, acetone, and ammonia with other amines.10 Sweet, musty or fishy are used to describe particular halitosis types. However, fish odour is non-specific for trimethylaminuria (TMAU),24 as is acetone for diabetes. All individuals have detectable breath acetone >400 ppb,25,26 especially when fasting. Fish odour can be perceived as musty and acetone as sweet. The sweet, musty aroma in liver failure has been termed fetor hepaticus.27 This is also described as faecal, 'the smell of dead mice' or 'the breath of the dead'.28

Other terms include 'denture odour',29 'uraemic fetor' in renal failure,30 and 'rotten egg' in poor oral hygiene. All these terms are subjective and open to misinterpretation. There is no standardisation in terminology, which has led to discrepancies developing where some authors use a term with one definition and others with different meaning.

-

Oral malodour, oral halitosis, tongue malodour, odontogenic halitosis, pathological halitosis, objective halitosis, genuine halitosis and intra-oral halitosis are used incorrectly as synonyms for halitosis.31 For example, oral malodour includes all odours originating orally, not just the tongue; but not all pathologic/objective halitosis originates orally

-

Pseudo-halitosis, psychosomatic halitosis, halitophobia, self-halitosis, imaginary halitosis non-genuine halitosis, delusional halitosis and phantom halitosis are also sometimes used interchangeably,32 but they not synonymous, for example, halitophobia describes a fear; self-halitosis describes clinically existent, self-producing odour; imaginary halitosis describes halitosis produced psychologically; and phantom halitosis is neurologic

-

Morning breath is sometimes used instead of physiologic halitosis, but these are also dissimilar. Not all 'morning breath' is physiologic.

New definition of halitosis

Objective halitosis has been defined as 'malodour with intensity beyond a socially acceptable level perceived'.7 This is independent from halitometric readings and subjective odour descriptions. This should be a basic definition of objective halitosis, but must be qualified with several important points:

-

A halitosis complaint may be objective, where there is an unpleasant odour endogenously produced anywhere in the body, emitted from the mouth and/or nose and detectable to others; or subjective, where there is no detectable odour to others but the patient complains of its presence

-

Anyone who complains of halitosis, objective or subjective, should be considered a 'halitosis patient'

-

Evidence of objective halitosis is a clinical picture built of (i) reliable reports from the patient's social environment for example, family members or close friends, (ii) patient's self declaration of halitosis, and to a lesser extent (iii) halitometric readings

-

A lack of complaints from the patient's social environment including family members, suggests that there is no objective halitosis. Furthermore, if there are no complaints from either the patient or his/her social environment, this usually implies that there is no need to diagnose halitosis or treat, even if halitometric measurements appear to indicate the presence of elevated VSC. As a rule, halitometers measure VSC, not halitosis

-

Halitosis is considered unpleasant by the patient and his/her social environment. If the odour is not perceived negatively, it is not halitosis

-

Halitosis is almost always chronic in nature, although it may be intermittent

-

Some diseases (tonsillitis, pharyngitis, etc) or transient oral flora or metabolic changes in the body may cause bad odour in the short term (<2 months), which disappears when the condition resolves. Such bad odours are called temporary halitosis

-

Some volatile foodstuffs possess specific odours (for example, garlic, onion) and may cause short term halitosis ('dietary odour'), as with certain medications or intoxications. All are called temporary halitosis, managed with reassurance and advice, and further diagnosis or treatment is unnecessary.

New classification of halitosis

Types 1-5 (Fig. 2) represent different odour mechanisms, which may be present in any combination at any time. Potentially, each type of pathologic halitosis (Type 1-5) is superimposed on physiologic odour (Type 0). At any given time, pathologic halitosis is the sum of the all these types sources, as well as their respective underlying physiologic contributions.

The relative contributions of these different physiologic and pathologic aetiologies is subject to interpersonal variation and may fluctuate even within hours in the same individual. Sometimes the level of one or more types may be so low as to give negligible contributions to the overall complaint, or there may be multiple contributing factors in the same patient. This can be recorded as Type 1 + 3, Type 2 + 4, Type 1 + 4 + 5 halitosis, etc. Previous classifications oversimplify halitosis, and this new classification is the most representative model proposed.

Type 0 halitosis: physiologic halitosis

Type 0 halitosis represents the sum of the physiologic contributions of oral, airway, gastroesophageal, blood-borne and subjective halitosis that are potentially present in every healthy person, in any combination. All healthy individuals have a certain level of bacterial activity in the mouth and on respiratory tract mucosae. In addition there is a potentially a negligible amount of gas leakage from the gastroesophageal tract, and blood gases are transferred to the exhaled breath during gas exchange in pulmonary alveoli. Therefore, minimal amounts of Types 1-5 potentially exist in health. The total level of odour and the relative contributions of these different sources of physiologic odour is subject to both interpersonal variation, and also variation in the same individual from one occasion to the next. One or multiple types may exist in any combination at any time, varying according to many different factors, including hydration, oral hygiene, microbiota, salivary flow rate, nature of last food consumption, biochemical, hormonal, mechanic activity of the body, fasting, sleep, digestive enzyme profile in gut, momentarily amino acid and electrolyte profile in serum etc. It is distinguished from oral halitosis (Table 1).

Type 1 halitosis: oral halitosis

The gases that contribute to Type 1 (oral) halitosis are (greatest to least): VSC, volatile organic compounds (VOC) and nitrogen containing gases (amines).33 The main VSC involved are hydrogen sulphide (H2S), methyl sulphide (CH3SH, or methyl mercaptan, MM), and dimethyl sulphide [(CH3)2S, DMS]. Nearly 700 different compounds have been detected orally,34 including indole, skatole, acetic acid and short chain acids (for example, butyric, valeric, isovaleric, lactic, caproic, propionic and succinic acids). In halitosis patients, the 30 most abundant VOC in mouth air are alkanes or alkane derivatives, and of these the most common are methyl benzene, tetramethyl butane, and ethanol.35 Alkanes are aromatic breakdown products from reactive oxygen species acting on inflamed tissues.35 Others report acetone, methenamine, isoprene, phenol, and D-limonene are the most abundant organic compounds in mouth air in oral halitosis patients. The organoleptic level of oral halitosis correlates with VSC,34 and amines (such as putrescine, cadaverine, and trimethylamine).36

The gases responsible for oral halitosis are by-products of protein and glycoprotein putrefaction by the oral microbiota. The dorso-posterior tongue is the most important halitogenic site, by virtue of having both the largest surface area and the highest bacterial load, within a densely populated biofilm.37,38,39 About 85% of oral halitosis cases are caused by poor oral hygiene, plaque stagnation areas, gingivitis, and tongue coating.31 However, a degree of oral bacterial action is continuously present in health, even with impeccable oral hygiene, and this constitutes the physiologic part of Type 1 halitosis.

Specific bacteria, especially anaerobes, are suggested to cause oral halitosis.40,41 In reality, most oral bacteria are potentially odorigenic, releasing VSC, VOC and/or amines. Depending upon the constituents of the gas produced by oral bacteria and ecologic factors in the mouth (for example, microbiota compositional fluctuations, available nutritional substrate, bacterial metabolism) momentarily determine the composition and level of odour. Therefore, the diagnostic value of the odour character at any one time is questionable. To consider some bacteria as odorigenic and others as non-odorigenic is oversimplification. In reality every bacterium is odorigenic, and there is a continuous spectrum from low to high degree of odour formation capability.33,42

Other possible origins of oral halitosis include: periodontal disease, acute necrotising ulcerative gingivitis, osteoradionecrosis, large carious cavities, blood/thrombi (for example, extraction sockets), ulceration, interdental food packing, oral prostheses (dentures, orthodontic appliances, bridges).

Type 2 halitosis: airway halitosis

Type 2 halitosis originates from the respiratory tract itself (rhinosinusitis, tonsillitis, pharyngitis, laryngitis, bronchitis, pneumonia), anywhere from nose to alveoli. Odorous gases produced by various respiratory pathoses are held in the exhaled breath and expressed via the nose or mouth. This should be distinguished from Type 4 (blood-borne) halitosis, where volatiles from the systemic circulation are transferred during gas exchange to the breath. Some studies report the proportion of halitosis cases that are due to upper respiratory tract pathology to be between 2.9 and 10%.31,43,44,45,46,47

Halitosis is considered a regional symptom of chronic rhinosinusitis, and some report as many as 50-70% will complain of halitosis.48,49 In paediatric patients, one of most frequent symptoms is halitosis together with cough, rhinorrhoea and sniffling,50 even when nasal obstruction, post-nasal exudate, pain, sneezing and secretion are clinically absent.51 Sinonasal anatomic variations (for example, agger nasi cells, pneumatisation of turbinates or septum; deviated nasal septum) are very commonly found together with mucosal pathoses including rhinosinusitis.52

Post nasal drip is where mucus drains onto the dorsal tongue via the nasopharynx.53 This is related to allergic rhinitis, however, the existence of post-nasal drip as a clinical entity is disputed as this occurs in health and there is no agreed definition or pathologic changes.54 Mucus stagnation provides a proteinaceous medium for more bacterial putrefaction, but the relationship between halitosis and post-nasal drip has not been formally investigated.

Obstructive nasal pathology causes mouthbreathing, possibly resulting in xerostomia and halitosis.13,55

Tonsillitis causes oedema and hypertrophy, which may obstruct orifices on tonsillar surface. This disrupts the cleansing flow of secretions, and desquamated epithelial and bacterial cells, extracellular matrix and food debris become trapped, leading to stagnation. Bacteria putrefy local substrate and release VOC and VSC, expressed on the breath as halitosis with a similar mechanism that operates on the tongue surface. Crypt debris may mineralise, similar to the transformation of dental plaque to dental calculus. These mineralised deposits are termed tonsilloliths (tonsil stones). The presence of tonsilloliths is strongly associated with abnormal VSC levels.46 They are asymptomatically present in up to 10% of the general population.56 Anaerobic bacteria detected in tonsilloliths include Eubacterium, Fusobacterium, Porphyromonas, Prevotella, Selenomonas and Tanerella spp., all associated with the production of VSCs.57

Odorous gases from the mouth or present in oronasal secretions can excite olfactory receptors and be perceived as halitosis,58 even if no halitosis can be detected halitometrically. This is retronasal olfaction and is usually misdiagnosed.

'Airway reflux' describes gaseous or liquid gastric contents refluxing to the pharynx, oral cavity, nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses or even the middle ear,59 and is sometimes said to be a cause of halitosis, however, there is little credible evidence for this mechanism.

Other respiratory tract causes of halitosis include: laryngitis, tracheitis, bronchitis, bronchiectasis, pneumonia, tuberculosis, nasal foreign bodies, rhinoliths, atrophic rhinitis (ozena), abscesses (peritonsillar, nasopharnygeal, lung), and carcinomas (nasal, sinuses, pharyngeal, lung).10,60,61,62,63,64,65

Type 3 halitosis: gastroesophageal halitosis

Type 3 halitosis is leakage of odorant volatiles from the stomach via the oesophagus to the mouth and nose. This should be distinguished from volatiles in the GI tract being absorbed into the systemic circulation and exhaled (Type 4, blood-borne halitosis). A degree of gastroesophageal reflux is considered normal, occurring in almost all individuals several times per day.66 In a study of 14 healthy individuals, 1.2 ml/10 min gas leakage from the stomach to the oesophagus while lying horizontal and 6.8 ml/10 min while sitting was demonstrated.67 If odorous, this constitutes the physiologic part of gastroesophageal halitosis.

Pathologic level of gastroesophageal halitosis is said to occur due to i) gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), ii) Helicobacter pylori related gastritis, or iii) other causes for example, gastrocolic fistulae, Zenker diverticulum and hypopharyngeal diverticulae.66 Falcao et al. argued that certain GI disorders can cause taste disturbance. Taste receptor cells are associated with lingual papillae, but also present on the palate, epiglottis and upper oesophagus. Low intensity acid reflux can cause phantom taste sensations, which may manifest as subjective halitosis.16

Evidence for GERD-related halitosis is contradictory. Some studies report self-reported/subjective halitosis complaints are associated with GERD.68,69,70,71 One study reported gastroesophageal pathology in less than 50% of patients complaining of halitosis,72 while others report that GI disorders may account for up to 5% of objective halitosis complaints.31 A systematic review investigated the relationship between GERD and halitosis (among other things). Three studies were included, and the authors concluded halitosis is a possible extra-oesophageal symptom of GERD,73 however, two of these studies utilised questionnaires (that is, subjective halitosis). Yoo et al. report H. pylori infection correlated with elevated VSC in mouth and mucosal erosions,74 posing halitosis as a potential biomarker to distinguish between erosive (200 ppb) and (75 ppb) non-erosive GERD.75 Gas chromatography on gastric juice and biopsies in these subjects found resolved 7.5 ppm significantly higher H2S and expression of VSC-releasing enzymatic activity in the erosive group, and 0.5 ppm in the non-erosive group.74 However, another study reported no significant difference in halitosis parameters when comparing erosive and nonerosive GERD.76 Others have suggested the stomach rarely causes halitosis10 and gastroscopy in halitosis patients is entirely unnecessary,12 as the findings do not correlate with halitosis.77 It has also been argued that there is no evidence that odorous substances are formed in the stomach.12 Another study reported no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of halitosis symptoms between children with GERD and those without.78

H. pylori infection also has a controversial role. H pylori possesses a strain-dependent ability to synthesise H2S and MM from combined cysteine-methionine substrate in vitro.79 Elevated levels of both hydrogen cyanide and hydrogen nitrate were detected on the breath of H. pylori infected patients compared to healthy controls;80 however, whether this represents Type 3 or Type 4 (blood-borne) halitosis is unknown.

Oral H. pylori colonisation without gastritis may cause Type 1 (oral) halitosis. PCR detected H. pylori in 6.4% (21/326) of saliva samples from non-dyspeptic individuals complaining of halitosis. H. pylori was associated with higher MM concentration.81

Improvements in halitosis (defined by various methodologies) following eradication therapy are reported.82,83,84,85,86,87 Positive correlation between H. pylori and halitosis is reported by some studies,88,89,90 however, some of these can be criticised for relying on self-reported halitosis rather than semi-objective breath analysis.91 Others report no statistically significant correlation.69,77,91,92,93

This mechanism is rarely responsible for halitosis, but cannot presently be dismissed due to several studies that support the idea that GI disease may cause halitosis.

Type 4 halitosis: blood-borne halitosis

Type 4 (blood-borne) halitosis is where volatile chemicals in the systemic circulation can transfer to exhaled breath during alveolar gas exchange and cause halitosis.94

Volatiles are endogenously produced, mostly by-products of biochemical metabolic processes.11 The concentration of volatiles on the exhaled breath reflects their respective arterial concentrations.24 Healthy subjects' breath contains 3,481 VOCs,95 constituting the phsyologic aspect of Type 4 halitosis (Table 2).

Methylated or low carbon containing alkanes, cyclic hydrocarbons, alcohols and aldehydes has an especially pungent odour when they exceed specific odour thresholds for the individual or his/her social environment, constituting pathologic Type 4 halitosis. The threshold concentration for any given chemical depends on the change in intensity (odour strength) with concentration and the odour character. There is also interpersonal variation in emotional reactions to detected odour; some may react positively and others negatively.108 A single volatile chemical can be perceived at lower concentrations than expected when it is combined in a mixture of thousands of VOC like the breath by interaction with other odorants and collective stimulation of olfactory receptors.

Artificial systems containing chemical sensor arrays for the detection of breath volatiles allow for profile readings of multiple compounds instead of single sensors for a single volatile.109 This is more favourable as breath odours are not limited to a single or a handful of gasses describable according to their individual threshold levels. Rather, breath odours are 'olfactory spectra' of breath. Every exhaled odorant gas should be suspected as potentially contributing, by varying degrees, to the overall perception of breath odour.

In pathologic Type 4 halitosis the concentrations and profile of exhaled gases is significantly different to those seen in health, depending on the pathology. Exhaled breath volatiles are reported in diabetes mellitus, sleep apnea, H. pylori infection, sickle cell disease, asthma, breast cancer, lung carcinoma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cystic fibrosis, liver diseases, cirrhosis, uraemia, kidney failure and TMAU.24,94

Breath alkanes have a pungent odour and are elevated in intestinal inflammation,110 for example, ulcerative colitis,111,112 Crohn's disease,112 in pulmonary tuberculosis,113 schizophrenia,114 pneumonia,115 asbestos-related disorders,116 stomach cancer,117 and angina pectoris.118 Pregnant females or pre-eclampsia patients have a specific breath gas profile, including undecane, 6-methyltridecane, 2-methylpentane, 5-methyltetradecane and 2-methylnonane.119 DMS, acetone, 2-butanone and 2-pentanone are reported in liver failure, including cirrhosis.27

The 'fetor hepaticus' of hepatic failure is largely caused by DMS, not ammonia.28 Elevated blood DMS ('dimethylsulphidemia'),28 was reported to be responsible for the majority of cases of blood borne halitosis.12

Body odour may accompany Type 4 halitosis as the same volatiles are also excreted during perspiration. This is sometimes termed blood-borne body odour and halitosis. An example is TMAU, a rare condition, classically characterised by fish odour in urine, sweat and breath.

When odorous chemical in blood circulation exceeds a critical level then it is secreted to breath, urine, tear, saliva and sweat. In such conditions body odour appears. In other circumstances, breath odour (Type 4 halitosis) is detected without body odour.

Another potential blood-borne mechanism may contribute to a halitosis complaint when blood-borne odorants stimulate olfactory receptors via their blood supply.16,120 Strong olfactory receptor responses can be triggered by intravascular injection of odorants in tracheotomised animals. Such odour perceptions are not occurring by the normal air-borne route, so there may not be measurable halitosis.

Type 5 halitosis: subjective halitosis

Subjective halitosis is a halitosis complaint without objective confirmation of halitosis by others or halitometer readings. Type 5 halitosis can be misdiagnosed if there are measurement errors or transient symptoms.

It can be considered normal for even mentally healthy individuals to worry occasionally about to be having halitosis.121 Such halitosis concern can be rationally dismissed by most healthy people who have a degree of psychological resilience that is capable of compensating for stressors. This normal level of concern for halitosis constitutes the 'physiologic' aspect of Type 5 halitosis.

Pathologic subjective halitosis can be categorised as psychologic or neurologic.

Psychologic causes

Psychologic factors can cause subjective halitosis. This is termed monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis,16 a type of obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorder,121 or olfactory reference syndrome (ORS). Seventy-five percent of ORS patients present with halitosis complaints,122 but obsession over other non-existent body odours, often in combination, are included. Others' behaviour (for example, opening windows, sniffing, touching noses etc) is misinterpreted as evidence of halitosis. Employment loss, divorce or suicidal ideation are reported.123 'Doctor shopping' to find clinicians to treat the non-existent odour may occur. However, some report that TMAU or other genuine odour symptoms can be misdiagnosed as ORS.124

It may be the case that the previously black and white thinking of objective halitosis on the one hand and psychologic halitosis on the other is an oversimplification. Instead, it might be more accurate to consider a spectrum, with entirely subjective halitosis at one extreme and entirely objective halitosis with no psychologic concern at the other. Most patients will fall somewhere between these two points.

When objective halitosis has not been treated it may cause the patient distress or social isolation and eventually over-concern about halitosis may develop. Even after the odour is reduced to physiologic levels, the negative psychosocial sequelae may persist, making these cases difficult to treat. Conversely, oversensitivity to physiologic odour may be the basis of a subjective halitosis with no history of objective halitosis.

Neurogenic causes

Traditionally, subjective halitosis complaints are attributed to psychologic factors, but at least some are neurologic. Nearly 200 disorders can cause chemosensory dysfunction (CSD).16 Dysosmia (disordered olfaction including parosmia and phantosmia) and dysgeusia (disordered gustation) present extensive differential diagnoses.

Olfaction and gustation are intimately interlinked at the neuronal level in the brain. The definition of subjective halitosis (pseudo-halitosis) has been broadened: 'the perception of an alteration in the quality of expired odour air, a symptom perceived only by the patient.'16 Many patients fail to distinguish between bad taste and bad odour. Gustatory stimuli may influence orthonasal and retronasal odorant perception.58

Side effects of medication, hypothyroidism, hyposalivation (another extensive differential), nutrient deficiency (zinc, copper, iron, and vitamins A and B12), trauma and tumours involving the olfactory centre in the brain, or nerve damage (glossopharyngeal, vagus, chorda tympani, olfactory), neurodegenerative diseases (Parkinson's, Alzheimer's and Huntington's disease), environmental pollutants (for example, smoking), drug abuse, certain oral hygiene products (for example, mouthwashes) and certain foodstuffs can all be potentially involved in subjective halitosis complaints by various mechanisms.16,125 As described previously, diabetes mellitus, GERD and blood-borne stimulation of taste and smell receptors via the blood circulation may also contribute to subjective halitosis.16,126

New terminology

Unhelpful terms no longer needed:

-

Many of the confusing array of synonyms used to describe a psychologic, subjective halitosis complaint (which would fall within Type 5 halitosis) are unneeded, including pseudo-halitosis, non-genuine halitosis, delusional halitosis, olfactory obsession, psico-olfactory sensitivity, olfactory depression, halitosis anxiety and imaginary halitosis

-

Subjective, descriptive terms such as sulphurous, ammoniacal, faecal, fishy or similar should be discontinued since they invite misunderstanding.

Useful terms that are retained:

-

Objective halitosis refers to any combination of Types 1-4, but should not refer to Type 1 (oral) halitosis exclusively

-

Morning breath is a temporarily increased physiologic halitosis during sleep and disappears soon after waking.127 Xerostomia is largely responsible,128 resulting from diminished salivary and respiratory secretion during sleep, especially when the mouth remains open. Proteinaceous substrates in saliva allows for microbial action, and release of VSC and other volatiles, thereby enhancing Type 1 and 2 halitosis. Increased breath ammonia, acetone,97,129 and isoprene,127 occur after overnight fasting. Intestinal gas builds up in the colon during sleep,130 possibly due to immobility and microbial fermentation of intestinal contents. More Type 4 halitosis might result, or possibly, more gas leakage from the gastroesophageal valve (that is, Type 3). All the above mechanisms may operate during sleep. The resultant halitosis upon waking can be termed morning breath, in reality an enhanced form of Type 0 halitosis

-

Psychosomatic halitosis should be retained, but the term should not be misused. Some hypothesise that anxiety enhances oral VSC production.131 This mechanism is correctly termed psychosomatic, since a physical symptom is being influenced by psychologic factors. This is the uniquely correct usage of the term 'psychosomatic halitosis', rather than previous meanings (see 'Previous terminology')

-

Self-halitosis has been used to describe a lack of objective halitosis even though the patient believes themselves to have halitosis,32 but it is better used to define endogenously produced, self-perceived odour, which is not a detectable odour to others. By true description, self-halitosis appears in three forms: retronasal olfaction, olfactory receptor responses triggered by blood-borne odorants, and phantom tastes/odours

-

Halitophobia should be retained with correct meaning. It refers to 'fear of having halitosis' but not 'untreated halitosis'.

New terms

-

Exogenous odour results from consumption of aromatic foodstuffs (for example, garlic, onion, spicy foods), beverages (for example, alcohol) or tobacco. Exogenous volatiles may be released transiently from residues of food or drink in the mouth, or released unchanged via the blood-borne mechanism after being absorbed. Such odours are distinguished from pathologic halitosis, for example, garlic smells like garlic. The terms garlic odour, spice odour, etc seem suitable. Dietary or temporary halitosis are also terms that could be argued to be useful

-

Halitosis is an endogenous odour because it is produced in the body.

Discussion

The new definition places less importance on organoleptic examination and single occasion halitometric reading, and instead places more emphasis on the declarations of the patient and his/her social environment. The reasoning for this follows.

Organoleptic examination

Organoleptic measurement is carried out by smelling the patient's breath then scoring the level of halitosis.7 However, the examiner does not smell a pure sample of mouth air, but rather a mixture of mouth air and alveolar air. The organoleptic examination does not distinguish between these, only subjectively assesses the overall odour level.

The perception of odorants depends upon several factors, including constant fluctuations in the clinician's individual threshold level for that specific odour, what was last smelled before the examination, the concentration and volatility of the molecules themselves, room temperature (gases are less volatile in lower temperatures), humidity of exhaled breath, how strongly the breath is blown into the examiner's nose (less forcefully expired breath will consist of less volume of air, and less odorant molecules will be carried to the examiner's olfactory epithelia), and lastly the examiner's concentration at that moment. All these parameters vary from one hour to the next and from one individual to the next, making this a subjective measure that does not reflect the actual level of odour. It can be suggested that self-applied organoleptic scoring (self-assessment) should be evaluated to monitorise prognosis.

Organoleptic examination is problematic,132 and objectionable to both dentists and to patients. Dislike or shame is experienced by 50% of patients with this examination (n = 283).133 Some use a privacy screen to prevent the patient from seeing the examiner during the examination.7 Examiners find it repulsive to smell a halitosis patient's breath.

Self-detection of halitosis correlated positively with actual halitosis only when subjects smelt their own saliva isolated from their mouth. Other methods did not correlate.134 Another study reported less correlation between self-detection of halitosis and clinical findings. The sensitivity and specificity of self-perceived oral malodour were 47.2% and 59.2%, respectively.135 The same author later compared 252 halitosis patients' self-estimation, organoleptic and halitometric results and found that self-estimated corresponded significantly with clinical oral malodour.136

Halitometers

Gas chromatography (GC), alone or combined with mass spectrometry (MS), is most frequently utilised for highly sensitive VSC detection (1-10 ppb). Nevertheless, routine application of these clinically is impractical given the expense and complexity, and the expertise required.94 More practical methods utilise colorimetric hydrogen sulphide sensors engineered both as an optical fibre, capable of measuring reflectance change of an immobilized reagent,137 and as thin reactive films of chromophores.138 A bio-electronic nose capable of detecting the oxygen consumption induced by an enzymatic reaction with methyl sulphide has also been developed.139 The Halimeter140 contains an electrochemical sensor for VSC. The semiconductor gas sensors Breathtron,141 constructed as a zinc oxide film with specificity to hydrogen sulphide and mercaptans.142 The GC-based OralChroma,143 is portable equipment capable of determining combined H2S, MM and DMS levels, with a 10 min response time and a detection limit of a few ppb. Twin Breasor,144 Diamond Probe/Perio 2000,145 Cyranose 320,146 and B/B Checker,147 are portable devices for detecting several gases including VSC and other odorous gases in mouth or breath air.148,149 Their accuracy is poor compared to GC and MS. They cannot distinguish one odour from another, and they have difficulty distinguishing individual compounds from the family of VSC.132

Almost all halitosis researchers and specialists use portable sulphide monitors (for example, Halimeter) to detect oral VSC.14 Good correlation exists between Halimeter readings and VSC concentration,35 and sulphur-producing bacteria levels.150 However, Halimeter readings are imprecise and misdiagnosis may result.151 The Halimeter has biexponential response to a constant concentration of VSC. Rapid (peak) and slow (plateau) responses differed. The total VSC in air samples was 2.7 times greater than at its peak concentration, but its plateau phase measurement is 25% greater than the actual concentration. A modified protocol measuring plateau instead of peak values is available, yielding more favorable correlation with the actual level of VSC.152

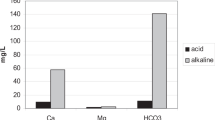

In order to investigate the Halimeter's ability to distinguish between VSC and other gases, having calibrated the Halimeter to ambient air, the aspirating tube was inserted into the headspace of some 250 ml commercial juice cartons immediately after opening. The Halimeter readings for apricot, apple, peach, cherry juices, buttermilk, soda, were 114, 352, 91, 48, 39, 47 ppb VSC respectively. In a similar experiment, the Halimeter reported VSC as if H2S is emitted from various flowers: daffodil, rose, jasmine were 255, 42, 73 ppb while 104 ppb was read near a sump, and 417 ppb near hand soap. When using another gas detector in the same conditions, all these flowers read with different percentages of VOC, not VSC.153 Such simple experiments show that the Halimeter seems to confuse VSC with other odorants, and may not be selective enough for halitosis. The OralChroma gives more comprehensive VSC level readings than the Halimeter,41 but it shares the VSC exclusivity limitation and therefore cannot fully determine the actual level of breath odour due to potential minor contributions from non-VSC gases.

New gas detectors capable of detecting sulphur and nitrogen containing gases, as well as VOCs should be developed for use in halitosis detection. There are industrial, portable gas detectors that are capable of detect more than four gas groups including VSC, NH3, or VOC that could potentially be utilised at one reading. A sensor system for monitoring the simple gases H2, CO, H2S, NH3, VOC and ethanol,154 and breath test kits including instruments to detect breath H2 and methane are available.155

Perturbation on threshold of halitosis

There is no consensus regarding what VSC reading corresponds to clinically present halitosis (Table 3).

Besides these data, some describe ranges of VSC readings, eg: 0-40, healthy; 41-60, physiologic; 61-80, slight; 81-110, moderate; 111-140, severe; over 141, very strong.162

VSC thresholds should be revisited to improve clinical utility.163 According to the new concepts described in this paper, there is no need to establish any precise VSC level that constitutes a halitosis diagnosis. Any patient complaining of halitosis is at least Type 5, even if objective halitosis is not diagnosed. Treatment should be targeted reducing pathologic halitosis to physiologic halitosis. Setting the goal at zero odour is unrealistic and arguably impossible.

There are three reasons to restrict the use of halitometers. Firstly, since baseline mouth air VSC concentrations fluctuate throughout day,151 halitometric reading at any particular time may not be representative. For this reason, multiple halitometric examinations carried out at different times throughout the day may be more representative compared to a single occasion in the dental clinic. Or cysteine challenge,164 should be applied to decide optimal VSC level of that individual.

Secondly, popular, portable halitometers are simply sulphide detectors, capable of detecting only VSC. However, nonsulphurous gases are also present in the mouth or breath, albeit in a lesser concentration than VSC. Halitometers are poor at distinguishing one odour from another. For example, in TMAU, the breath could be malodorous due to the presence of TMA and VSC levels may be under the normal range in such patients. Thus, examiners may misdiagnose some objective halitosis cases as if subjective halitosis by relying entirely on the specifity of halitometers.

Thirdly, there is no scientifically accepted quantitative threshold between physiologic odour and pathologic halitosis.

References

Quirynen M, Van den Velde S, Vandekerckhove B, Dadamio J . Oral Malodor. In Newman M G, Takei H H, Klokkevold P R, Carranza F A (eds) Carranza's clinical periodontology. 11th ed. pp 331–338. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier/Saunders, 2012.

Lindhe J, Lang N P, Karring T (eds) Clinical periodontology and implant dentistry. 5th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Munksgaard, 2008.

Cortelli J R, Barbosa M D, Westphal M A . Halitosis: a review of associated factors and therapeutic approach. Braz Oral Res 2008; 22(Suppl 1): 44–54.

Outhouse T L, Al-Alawi R, Fedorowicz Z, Keenan J V . Tongue scraping for treating halitosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; CD005519.

Fedorowicz Z, Aljufairi H, Nasser M, Outhouse T L, Pedrazzi V . Mouthrinses for the treatment of halitosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; CD006701.

Miyazaki H, Arao M, Okamura K, Kawaguchi Y, Toyofuku A, Hoshi K, Yaegaki K . Tentative classification of halitosis and its treatment needs. Niigata Dental Journal 1999; 32: 7–11.

Yaegaki K, Coil J M . Examination, classification, and treatment of halitosis; clinical perspectives. J Can Dent Assoc 2000; 66: 257–261.

Murata T, Yamaga T, Iida T, Miyazaki H, Yaegaki K . Classification and examination of halitosis. Int Dent J 2002; 52(Suppl 3): 181–186.

Yaegaki K, Coil J M . Genuine halitosis, pseudo-halitosis, and halitophobia: classification, diagnosis, and treatment. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2000; 21: 880–886, 888–889.

Tangerman A, Winkel E G . Extra-oral halitosis: an overview. J Breath Res 2010; 4: 017003.

Tangerman A . Halitosis in medicine: a review. Int Dent J 2002; 52(Suppl 3): 201–206.

Tangerman A, Winkel E G . Intra-and extra-oral halitosis: finding of a new form of extra-oral blood-borne halitosis caused by dimethyl sulphide. J Clin Periodontol 2007; 34: 748–755.

Motta L J, Bachiega J C, Guedes C C, Laranja L T, Bussadori S K . Association between halitosis and mouth breathing in children. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011; 66: 939–942.

Richter J L . Diagnosis and treatment of halitosis. Compend Contin Educ Dent 1996; 17: 370–372, 374–376.

Iwu C O, Akpata O . Delusional halitosis. Review of the literature and analysis of 32 cases. Br Dent J 1990; 168: 294–296.

Falcão D P, Vieira C N, Batista de Amorim R F . Breaking paradigms: a new definition for halitosis in the context of pseudo-halitosis and halitophobia. J Breath Res 2012; 6: 017105.

Seemann R, Bizhang M, Djamchidi C, Kage A, Nachnani S . The proportion of pseudo-halitosis patients in a multidisciplinary breath malodour consultation. Int Dent J 2006; 56: 77–81.

Videbech T . Chronic olfactory paranoid syndromes. A contribution to the psychopathology of the sense of smell. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1966; 42: 183–213.

Takahashi T . A social club spontaneously formed by ex-patients who had suffered from anthropophobia (Taijin kyofu (sho)). Int J Soc Psychiatry 1975; 21: 137–140.

Rosenberg M, Leib E . Introduction. In Rosenberg M (ed). Bad breath: research perspectives. 2nd ed. pp 9–13. Tel Aviv: Ramot Publishing, Tel Aviv University; 1997.

Lochner C, Stein D J . Olfactory reference syndrome: diagnostic criteria and differential diagnosis. J Postgrad Med 2003; 49: 328–331.

Phillips K A . How to help patients with olfactory reference syndrome. Delusion of body odour causes shame, social isolation. The Journal of Family Practice 2007; 6: 1.

Zaitsu T, Ueno M, Shinada K, Wright F A, Kawaguchi Y . Social anxiety disorder in genuine halitosis patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011; 9: 94.

Whittle C L, Fakharzadeh S, Eades J, Preti G . Human breath odours and their use in diagnosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007; 1098: 252–266.

Smith D, Turner C, Spaněl P . Volatile metabolites in the exhaled breath of healthy volunteers: their levels and distributions. J Breath Res 2007; 1: 014004.

Enderby B, Lenney W, Brady M, Emmett C, Spaněl P, Smith D . Concentrations of some metabolites in the breath of healthy children aged 7–18 years measured using selected ion flow tube mass spectrometry (SIFT-MS). J Breath Res 2009; 3: 036001.

Van den Velde S, Nevens F, Van Hee P, van Steenberghe D, Quirynen M . GC-MS analysis of breath odour compounds in liver patients. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2008; 875: 344–348.

Harvey-Woodworth C N . Dimethylsulphidemia: the significance of dimethyl sulphide in extra-oral, blood borne halitosis. Br Dent J 2013; 214: E20.

Coulthwaite L, Verran J . Development of an in vitro denture plaque biofilm to model denture malodour. J Breath Res 2008; 2: 017004.

Davies S, Spanel P, Smith D . Quantitative analysis of ammonia on the breath of patients in end-stage renal failure. Kidney Int 1997; 52: 223–228.

Bollen C M, Beikler T . Halitosis: the multidisciplinary approach. Int J Oral Sci 2012; 4: 55–63.

Yaegaki K, Coil J M . Clinical dilemmas posed by patients with psychosomatic halitosis. Quintessence Int 1999; 18: 328–333.

Aydin M . Halitosis. In Aydin M, Mısırlıgil A (eds). Oral microbiology. pp 97–104. Ankara: MN Medical & Nobel, 2012.

Van den Velde S, van Steenberghe D, Van Hee P, Quirynen M . Detection of odorous compounds in breath. J Dent Res 2009; 88: 285–289.

Phillips M, Cataneo R N, Greenberg J, Munawar M, Nachnani S, Samtani S . Pilot study of a breath test for volatile organic compounds associated with oral malodour: evidence for the role of oxidative stress. Oral Dis 2005; 11(Suppl 1): 32–34.

Dadamio J, Van Tornout M, Van den Velde S, Federico R, Dekeyser C, Quirynen M . A novel and visual test for oral malodour: first observations. J Breath Res 2011; 5: 046003.

Hartley M G, El-Maaytah M A, McKenzie C, Greenman J . The tongue microbiota of low odour and malodourous individuals Micro Ecol Health Dis 2009; 9: 215–223.

Hess J, Greenman J, Duffield J . Modelling oral malodour from a tongue biofilm. J Breath Res 2008; 2: 017003.

Aydin M . Anaerobic bacteria and anaerobism; Microbial biofilms and aerosols. In Cengiz T, Mısırlıgil A, Aydin M (eds) Microbiology in dentistry and medicine. pp 175–180; 569–576. Ankara: Güneş Medical, 2004.

Kozeowski Z, Mikeaszewska B B, Konopka T, Kawa Z D, Lewcyzk E . Using a Halitometer to verify the symptoms of halitosis. Adv Clin Exp Med 2007; 16: 411–416.

Salako N O, Philip L . Comparison of the use of the Halimeter and the Oral Chroma™ in the assessment of the ability of common cultivable oral anaerobic bacteria to produce malodorous volatile sulphur compounds from cysteine and methionine. Med Princ Pract 2011; 20: 75–79.

Aydin M . Odorigenic bacteria in halitosis. Istanbul: Nobel medikal, 2008.

Zürcher A, Filippi A . Findings, diagnoses and results of a halitosis clinic over a seven year period. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed 2012; 122: 205–216.

Delanghe G, Bollen C, Desloovere C . Halitosis-foetor ex ore. Laryngorhinootologie 1999; 78: 521–524.

Quirynen M, Dadamio J, Van den Velde S et al. Characteristics of 2000 patients who visited a halitosis clinic. J Clin Periodontol 2009; 36: 970–975.

Bollen C M, Rompen E H, Demanez JP . Halitosis: a multidisciplinary problem. Rev Med Liege 1999; 54: 32–36.

Fletcher S M, Blair P A . Chronic halitosis from tonsilloliths: a common aetiology. J La State Med Soc 1988; 140: 7–9.

Lanza D C . Diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl 2004; 193: 10–14.

Bunzen D L, Campos A, Leão F S, Morais A, Sperandio F, Caldas Neto S . Efficacy of functional endoscopic sinus surgery for symptoms in chronic rhinosinusitis with or without polyposis. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2006; 72: 242–246.

Tatli M M, San I, Karaoglanoglu M . Paranasal sinus computed tomographic findings of children with chronic cough. Int J Paediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2001; 60: 213–217.

Schlosser R J, Harvey R J . Diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis. In Thaler E R, Kennedy D W (eds) Rhinosinusitis. pp 43. New York: Springer LLC, 2008.

Yücel A, Dereköy F S, Yılmaz M D, Altuntaş A . Effects of sinonasal anatomical variations on paranasal sinus infections. The Medical Journal of Kocatepe 2004; 5: 43–47.

Amir E, Shimonov R, Rosenberg M . Halitosis in children. J Paediatr 1999; 134: 338–343.

Morice A H . Post-nasal drip syndrome-a symptom to be sniffed at? Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2004; 17: 343–345.

Ng D K, Chow P Y, Kwok K L . Halitosis and the nose. Hong Kong Med J 2005; 11: 71–72.

Stoodley P, Debeer D, Longwell M et al. Tonsillolith: not just a stone but a living biofilm. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009; 141: 316–321.

Tsuneishi M, Yamamoto T, Kokeguchi S, Tamaki N, Fukui K, Watanabe T . Composition of the bacterial flora in tonsilloliths. Microbes Infect 2006; 8: 2384–9.

Welge-Lüssen A, Husner A, Wolfensberger M, Hummel T . Influence of simultaneous gustatory stimuli on orthonasal and retronasal olfaction. Neurosci Lett 2009; 454: 124–128.

Koufman J A, Aviv J E, Casiano R R, Shaw G Y . Laryngopharyngeal reflux: position statement of the committee on speech, voice, and swallowing disorders of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002; 127: 32–35.

Brent A . Odour - unusual. In Fleisher G R, Ludwig S (eds) Textbook of paediatric emergency medicine 6th ed. pp 402–405. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.

Sethi S, Nanda R, Chakraborty T . Clinical application of volatile organic compound analysis for detecting infectious diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev 2013; 26: 462–475.

Shirasu M, Touhara K . The scent of disease: volatile organic compounds of the human body related to disease and disorder. J Biochem 2011; 150: 257–266.

Brehmer D, Riemann R . The rhinolith-a possible differential diagnosis of a unilateral nasal obstruction. Case Rep Med 2010; 2010: 845671.

de Shazo R D, Stringer S P . Atrophic rhinosinusitis: progress toward explanation of an unsolved medical mystery. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 11: 1–7.

Mishra A, Kawatra R, Gola M . Interventions for atrophic rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 2: CD008280.

Hirano I, Kahrilas P J, Pandolfino J E, Richter J E, Soll A H, Graham D Y . In Yamada T, Alpers D H (eds) Textbook of gastroenterology. 5th ed. pp. 732, 742, 772, 951. Chichester: Blackwell Publishingm 2009.

Wyman J B, Dent J, Heddle R, Dodds W J, Toouli J, Downton J . Control of belching by the lower oesophageal sphincter. Gut 1990; 31: 639–646.

Di Fede O, Di Liberto C, Occhipinti G et al. Oral manifestations in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a single-centre case-control study. J Oral Pathol Med 2008; 37: 336–340.

Struch F, Schwahn C, Wallaschofski H et al. Self-reported halitosis and gastro-esophageal reflux disease in the general population. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23: 260–266.

Moshkowitz M, Horowitz N, Leshno M, Halpern Z . Halitosis and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a possible association. Oral Dis 2007; 13: 581–585.

Saberi-Firoozi M, Khademolhosseini F, Yousefi M, Mehrabani D, Zare N, Heydari S T . Risk factors of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Shiraz, southern Iran. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13: 5, 486–491.

Kinberg S, Stein M, Zion N, Shaoul R . The gastrointestinal aspects of halitosis. Can J Gastroenterol 2010; 24: 552–556.

Marsicano J A, de Moura-Grec P G, Bonato R C, Sales-Peres Mde C, Sales-Peres A, Sales-Peres S H. Gastroesophageal reflux, dental erosion, and halitosis in epidemiological surveys: a systematic review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 25: 135–141.

Yoo S H, Jung H S, Sohn W S et al. Volatile sulphur compounds as a predictor for esophagogastroduodenal mucosal injury. Gut Liver 2008; 2: 113–118.

Kim J G, Kim Y J, Yoo S H et al. Halimeter ppb levels as the predictor of erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gut Liver 2010; 4: 320–325.

Kislig K, Wilder-Smith C H, Bornstein M M, Lussi A, Seemann R . Halitosis and tongue coating in patients with erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease versus nonerosive gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Oral Investig 2013; 17: 159–165.

Tas A, Köklü S, Yüksel I, Başar O, Akbal E, Cimbek A . No significant association between halitosis and upper gastrointestinal endoscopic findings: a prospective study. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011; 124: 3, 707–710.

Carr M M, Nguyen A, Nagy M, Poje C, Pizzuto M, Brodsky L . Clinical presentation as a guide to the identification of GERD in children. Int J Paediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2000; 54: 27–32.

Lee H, Kho H S, Chung J W, Chung S C, Kim Y K . Volatile sulphur compounds produced by Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Gastroenterol 2006; 40: 421–426.

Lechner M, Karlseder A, Niederseer D et al. H. pylori infection increases levels of exhaled nitrate. Helicobacter 2005; 10: 385–390.

Suzuki N, Yoneda M, Naito T et al. Detection of Helicobacter pylori DNA in the saliva of patients complaining of halitosis. J Med Microbiol 2008; 57: 1553–1559.

Katsinelos P, Tziomalos K, Chatzimavroudis G et al. Eradication therapy in Helicobacter pylori-positive patients with halitosis: long-term outcome. Med Princ Pract 2007; 16: 119–123.

Serin E, Gumurdulu Y, Kayaselcuk F, Ozer B, Yilmaz U, Boyacioglu S . Halitosis in patients with Helicobacter pylori-positive non-ulcer dyspepsia: an indication for eradication therapy? Eur J Intern Med 2003; 14: 45–48.

Shashidhar H, Peters J, Lin C H, Rabah R, Thomas R, Tolia V . A prospective trial of lansoprazole triple therapy for paediatric Helicobacter pylori infection. J Paediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000; 30: 276–282.

Gasbarrini A, Ojetti V, Pitocco D et al. Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus affects eradication rate of Helicobacter pylori infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999; 11: 713–716.

Ierardi E, Amoruso A, La Notte T et al. Halitosis and Helicobacter pylori: a possible relationship. Dig Dis Sci 1998; 43: 2733–2737.

Tiomny E, Arber N, Moshkowitz M, Peled Y, Gilat T . Halitosis and Helicobacter pylori. A possible link? J Clin Gastroenterol 1992; 15: 236–237.

Chen X, Tao D Y, Li Q, Feng X P . The relationship of halitosis and Helicobacter pylori. Shanghai Kou Qiang Yi Xue 2007; 16: 236–238.

Adler I, Denninghoff V C, Alvarez M I, Avagnina A, Yoshida R, Elsner B . Helicobacter pylori associated with glossitis and halitosis. Helicobacter 2005; 10: 312–317.

Li X B, Liu W Z, Ge Z Z et al. Analysis of clinical characteristics of dyspeptic symptoms in Shanghai patients. Chin J Dig Dis 2005; 6: 62–67.

Tangerman A, Winkel E G, de Laat L, van Oijen A H, de Boer W A . Halitosis and Helicobacter pylori infection. J Breath Res 2012; 6: 017102.

Dore M P, Fanciulli G, Tomasi P A et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms and Helicobacter pylori infection in school-age children residing in Porto Torres, Sardinia, Italy. Helicobacter 2012; 17: 369–373.

Imanzadeh F, Imanzadeh A, Sayyari A A, Yagenah M, Javaherizadeh H, Hatamian B . Helicobacter pylori infection; in cases with and without subjective halitosis. Professional Med J 2010; 17: 543–545.

Ciaffoni L, Peverall R, Ritchie G A . Laser spectroscopy on volatile sulphur compounds: possibilities for breath analysis. J Breath Res 2011; 5: 024002.

Phillips M, Herrera J, Krishnan S, Zain M, Greenberg J, Cataneo R N . Variation in volatile organic compounds in the breath of normal humans. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl 1999; 729: 75–88.

Diskin A M, Spanel P, Smith D . Time variation of ammonia, acetone, isoprene and ethanol in breath: a quantitative SIFT-MS study over 30 days. Physiol Meas 2003; 24: 107–119.

Schmidt F M, Vaittinen O, Metsälä M et al. Ammonia in breath and emitted from skin. J Breath Res 2013; 7: 017109.

Wang T, Pysanenko A, Dryahina K, Spaněl P, Smith D . Analysis of breath, exhaled via the mouth and nose, and the air in the oral cavity. J Breath Res 2008; 2: 037013.

Turner C, Spanel P, Smith D . A longitudinal study of methanol in the exhaled breath of 30 healthy volunteers using selected ion flow tube mass spectrometry, SIFT-MS. Physiol Meas 2006; 27: 637–648.

Turner C, Parekh B, Walton C, Spanel P, Smith D, Evans M . An exploratory comparative study of volatile compounds in exhaled breath and emitted by skin using selected ion flow tube mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 2008; 22: 526–532.

Turner C, Spanel P, Smith D . A longitudinal study of ethanol and acetaldehyde in the exhaled breath of healthy volunteers using selected-ion flow-tube mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 2006; 20: 61–68.

Kharitonov S A, Barnes P J . Biomarkers of some pulmonary diseases in exhaled breath. Biomarkers 2002; 7: 1–32.

Phillips M, Greenberg J, Cataneo R N . Effect of age on the profile of alkanes in normal human breath. Free Radic Res 2000; 33: 57–63.

Blom H J, Tangerman A . Methanethiol metabolism in whole blood. J Lab Clin Med 1988; 111: 606–610.

Hamilton L H . Breath tests and gastroeneterology. 2nd ed. Milwaukee: Quintron Co, 1998.

Probert C S, Ahmed I, Khalid T, Johnson E, Smith S, Ratcliffe N . Volatile organic compounds as diagnostic biomarkers in gastrointestinal and liver diseases. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2009; 18: 337–343.

Phillips M . Breath tests in medicine. Sci Am 1992; 267: 74–79.

Leonardos G, Kendall D, Barnard N . Odour threshold determinations of 53 odorant chemicals. Japca J Air Waste Ma 1969; 19.

Bofan M, Mores N, Baron M et al. Within-day and between-day repeatability of measurements with an electronic nose in patients with COPD. J Breath Res 2013; 7: 017103.

Kokoszka J, Nelson R L, Swedler W I, Skosey J, Abcarian H . Determination of inflammatory bowel disease activity by breath pentane analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 1993; 36: 597–601.

Sedghi S, Keshavarzian A, Klamut M, Eiznhamer D, Zarling E J . Elevated breath ethane levels in active ulcerative colitis: evidence for excessive lipid peroxidation. Am J Gastroenterol 1994; 89: 2217–2221.

Pelli M A, Trovarelli G, Capodicasa E, De Medio G E, Bassotti G . Breath alkanes determination in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum 1999; 42: 71–76.

Phillips M, Dalay V B, Bothamley G et al. Breath biomarkers of active pulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 2010; 90: 145–151.

Phillips M, Erickson G A, Sabas M, Smith J P, Greenberg J . Volatile organic compounda in breath of patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Pathol 1995; 48: 466–469.

Julak J, Stranska E, Rosova U, Geppert H, Spanel P, Smith D . Bronchoalveolar lavage examined by solid phase microextraction, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and selected ion flow tube mass spectrometry. J Microbiol Methods 2006; 65: 76–86.

Chapman E A, Thomas P S, Yates D H . Breath analysis in asbestos-related disorders: a review of the literature and potential future applications. J Breath Res 2010; 4: 034001.

Ligor T, Szeliga J, Jackowski M, Buszewski B . Preliminary study of volatile organic compounds from breath and stomach tissue by means of solid phase microextraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Breath Res 2007; 1: 016001.

Phillips M, Cataneo R N, Greenberg J . Grodman R, Salazar M . Breath markers of oxidative stress in patients with instable angina. Hearth Dis 2003; 5: 85–99.

Moretti M, Phillips M, Abouzeid A, Cataneo R N, Greenberg J . Increased breath markers of oxidative stress in normal pregnancy and in preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 190: 1184–1190.

Maruniak J A, Silver W L, Moulton D G . Olfactory receptors respond to blood-borne odorants. Brain Res 1983; 265: 312–316.

Stein D J, Le Roux L, Bouwer C, Van Heerden B . Is olfactory reference syndrome an obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorder?: two cases and a discussion. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 10: 96–99.

Phillips K A, Menard W . Olfactory reference syndrome: demographic and clinical features of imagined body odour. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2011; 33: 398–406.

Cruzado L, Cáceres-Taco E, Calizaya J R . Apropos of an olfactory reference syndrome case. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2012; 40: 234–238.

Wise P M, Eades J, Tjoa S, Fennessey P V, Preti G . Individuals reporting idiopathic malodour production: demographics and incidence of trimethylaminuria. Am J Med 2011; 124: 1058–1063.

Bromley S M . Smell and taste disorders: a primary care approach. Am Fam Physician 2000; 61: 427–436, 438.

Pacheco-Galván A, Hart S P, Morice A H . Relationship between gastro-oesophageal reflux and airway diseases: the airway reflux paradigm. Arch Bronconeumol 2011; 47: 195–203.

Cailleux A, Allain P . Isoprene and sleep. Life Sci 1989; 44: 1877–1880.

Nachnani S . The effects of oral rinse on halitosis. J Calif Dent Assoc 1997; 25: 145–150.

Schwarz K, Pizzini A, Arendacká B et al. Breath acetone-aspects of normal physiology related to age and gender as determined in a PTR-MS study. J Breath Res 2009; 3: 027003.

Tangerman A . Measurement and biological significance of the volatile sulphur compounds hydrogen sulphide, methanethiol and dimethyl sulphide in various biological matrices. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2009; 877: 3366–3377.

Calil C M, Klein F . Influence of anxiety on the production of oral volatile sulphur compounds. Life Sci 2006; 79: 660–664.

Oral malodor. ADA council on scientific affairs. J Am Dent Assoc 2003; 134: 209–214

Aydin M . Gas measurement protocols in halitosis patients. (Unpublished data)

Rosenberg M, Kozlovsky A, Gelernter I et al. Self-estimation of oral malodour. J Dent Res 1995; 74: 1577–1582.

Pham T A, Ueno M, Shinada K, Kawaguchi Y . Comparison between self-perceived and clinical oral malodour. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2012; 113: 70–80.

Pham T A . Comparison between self-estimated and clinical oral malodour. Acta Odontol Scand 2013; 71: 263–270.

Fernández J R, Pereiro R, Medel A S . Optical fibre sensor for hydrogen sulphide monitoring in mouth air. Analytica Chimica Acta 2002; 471: 13–23.

Wallace K J, Cordero S R, Tan C P, Lynch V M, Anslyn E V . A colorimetric response to hydrogen sulphide. Sens Actuat B Chem 2007; 120: 362–367.

Mitsubayashia K, Minamide T, Otsuka K, Kudo H, Saito A . Optical bio-sniffer for methyl mercaptan in halitosis. Analytica Chimica Acta 2006; 573–574, 575–580.

Halimeter® Interscan Corporation. Measure bad breath scientifically. Chatsworth, CA, USA: Halimeter®. Online information available at http://www.halimeter.com/the-halimeter-measure-bad-breath-scientifically/ (accessed March 2014).

New Cosmos Electric Co., Ltd. Breathtron® . Osaka, Japan: New Cosmos Electric Co., Ltd. Online information available at http://www.new-cosmos.co.jp/en/profile.html (accessed March 2014).

Tanda N, Washio J, Ikawa K, Suzuki K, Koseki T . Iwakura M. A new portable sulphide monitor with a zinc-oxide semiconductor sensor for daily use and field study. J Dent 2007; 35: 552–557.

Abimedical Corporation. OralChroma™ . Osaka, Japan: Abimedical Corporation. Online information available at http://www.abimedical.com/en/medical/product_01.html (accessed March 2014).

Yaegaki K, Brunette DM, Tangerman A, Choe YS, Winkel EG, Ito S, Kitano T, Ii H, Calenic B, Ishkitiev N, Ima T. Standardization of clinical protocols in oral malodor research. J Breath Res 2012; 6: 017101.

Diamond General Development Corp. Diamond Probe/Perio 2000. Online information available at http://www.e-dental.com/doc/periodontal-probe-0001 (accessed March 2014).

Intopsys. Cyranose® 320. Cyranose Electronic Nose. Online information available at http://www.sensigent.com/products/cyranose.html (accessed March 2014).

Tamaki N, Kasuyama K, Esaki M, Toshikawa T, Honda SI, Ekuni D, Tomofuji T, Morita M . A new portable monitor for measuring odorous compounds in oral, exhaled and nasal air. BMC Oral Health 2011; 11: 15.

Cheng Z J, Warwick G, Yates D H, Thomas P S . An electronic nose in the discrimination of breath from smokers and non-smokers: a model for toxin exposure. J Breath Res 2009; 3: 036003.

Tamaki N, Kasuyama K, Esaki M et al. A new portable monitor for measuring odorous compounds in oral, exhaled and nasal air. BMC Oral Health 2011; 11: 15.

Pratten J, Pasu M, Jackson G, Flanagan A, Wilson M . Modelling oral malodour in a longitudinal study. Arch Oral Biol. 2003; 48: 737–743.

Yaegaki K, Brunette D M, Tangerman A et al. Standardization of clinical protocols in oral malodour research. J Breath Res 2012; 6: 017101.

Furne J, Majerus G, Lenton P, Springfield J, Levitt D G, Levitt M D . Comparison of volatile sulphur compound concentrations measured with a sulphide detector vs. gas chromatography. J Dent Res 2002; 81: 140–143.

Aydın M . Treatment of halitosis. presented at: 6th international congres of the Istanbul University Dentistry Faculty 2013 Nov 21-23, Istanbul, Türkiye

Costello B P, Ewen R J, Ratcliffe N M . A sensor system for monitoring the simple gases hydrogen, carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulphide, ammonia and ethanol in exhaled breath. J Breath Res 2008; 2: 037011.

QuinTron. BreathTracker: breath hydrogen and methane anaylsis with sample correction feature. USA: QuinTron. Online ifnromation available at http://www.quintron-eu.com/catalog/11_QT02444_Catalog.pdf (accessed March 2014).

Rösing C K, Loesche W . Halitosis: an overview of epidemiology, aetiology and clinical management. Braz Oral Res 2011; 25: 466–471.

Lin M I, Flaitz C M, Moretti A J, Seybold S V, Chen J W . Evaluation of halitosis in children and mothers. Paediatr Dent 2003; 25: 553–558.

Suzuki N, Yoneda M, Naito T, Iwamoto T, Hirofuji T . Relationship between halitosis and psychologic status. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008; 106: 542–547.

Halimeter. Halimeter® simplified operating instructions. Online manual available at http://www.halimeter.com/operating-instructions/ (accessed March 2014).

Suzuki N, Yoneda M, Naito T et al. Association between oral malodour and psychological characteristics in subjects with neurotic tendencies complaining of halitosis. Int Dent J 2011; 61: 57–62.

Tanaka M, Anguri H, Nishida N, Ojima M, Nagata H, Shizukuishi S . Reliability of clinical parameters for predicting the outcome of oral malodour treatment. J Dent Res 2003; 82: 518–522.

Nachnani S . Efficacy of zinc chloride based mouth rinse (BreathRx™) compared to chlorine dioxide based mouth rinse (Oxyfresh™). UCLA School of Dentistry, 2000. Online article available at http://www.halitosis-research.com/Zinc_Chloride_Compared_to_Chlorine_Dioxide_Mouthrinse.html (accessed March 2014).

Vandekerckhove B, Van den Velde S, De Smit M et al. Clinical reliability of non-organoleptic oral malodour measurements. J Clin Periodontol 2009; 36: 964–969.

Kleinberg I, Codipilly D M . Cystein challenge testing: a powerful tool for examining oral malodour processes and treatments in vivo. Int Dent J 2002; 52: 221–228.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aydin, M., Harvey-Woodworth, C. Halitosis: a new definition and classification. Br Dent J 217, E1 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.552

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.552

This article is cited by

-

Olfactory reference disorder—a review

Middle East Current Psychiatry (2023)

-

Volatile sulfide compounds and oral microorganisms on the inner surface of masks in individuals with halitosis during COVID-19 pandemic

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Volatile sulphur compounds in people with chronic kidney disease and the impact on quality of life

Odontology (2021)

-

The OralChromaTM CHM-2: a comparison with the OralChromaTM CHM-1

Clinical Oral Investigations (2020)

-

The Halitosis Consequences Inventory: psychometric properties and relationship with social anxiety disorder

BDJ Open (2018)