Key Points

-

Examines the survival of restorations in root filled and non-root filled teeth.

-

Suggests that teeth with root canal fillings have less time before re-intervention than teeth without root canal fillings.

-

Suggests that teeth restored with crowns during the same course of treatment as the root canal filling was placed have a longer time before re-intervention than those restored with plastic restorations.

Abstract

Aim To consider the survival of restorations in root filled and non-root filled teeth.

Methods A data set was established consisting of patients, 18 years or older. For each patient on the database with a tooth restored with a direct or indirect restoration with or without a root filling, the subsequent history of intervention on that tooth was consulted, and the next date of intervention, if any could be found in the data set, was obtained. Thus a data set was created of restored teeth and whether they have also received root fillings, with the dates of restoration and root filling placement and the dates, if any, of re-intervention. Modified Kaplan-Meier statistical analysis was used to quantify the distribution of time to intervention.

Results Data for over 80,000 different adult patients were analysed, of whom 46% were male and 54% female. A total of 538,967 restoration placements were obtained from the data over a period of 11 years, of which 30,073 were root fillings.

Conclusions Examination of the survival of restorations in teeth with and without root canal fillings indicated that those with root canal fillings have shorter intervals before re-intervention than teeth without root fillings. Restorations on root canal treated anterior teeth with post and cores had the lowest survival time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Root fillings in the general dental services

While direct placement restorations comprise the largest volume of restorations placed within the National Health Service General Dental Services (GDS) in England and Wales,1 there are, nevertheless, over a million teeth that receive root fillings in any given year within the GDS, at a cost of approximately £50 million between 2001 and 2004 (Table 1).1,2,3,4

It may be considered that the survival of restorations, including root fillings, is of interest not only to the patients who receive them, but also to third party funders, government, the clinician and his or her managers. The influence of a root treatment on the prognosis of a restored tooth may also be of interest.

Assessing outcome

The interval between successive interventions is a statistical proxy for the 'life' of a restoration, but it must be recognised that there are many other measures in use in the world of dental research. These vary from a variety of administrative rules, such as those developed by Robinson,5 to assessment by researchers using, for example, the USPHS criteria.6

In this study, the date of restoration and root canal filling placement was taken to be the last date recorded in the payment claim in respect of the course of treatment. In most cases this was the date of completion of treatment, when the dentist discharged the patient at the end of the course of treatment. The end of the life of a filling is conceptually more difficult, and it also strays into the issue of censoring, which has previously been discussed.7 Briefly, in this regard, censoring is important because, in most restorations, we are seeing only part of the life of the restoration and it is important to know how much of that life we are seeing. Kaplain-Meier analysis deals with records that have a known period of observation, either to completion or a time of censorship. The modification to Kaplan-Meier previously described and used by Lucarotti8 is to use Kaplan-Meier, but in some cases, the date of censoring has to be estimated. In this paper, the definition of the end of the life of a restoration was taken as the date of acceptance for the next course of treatment in which the tooth received an intervention.

Outcome of restorations placedin the general dental services

A previous study,9 which analysed time to re-intervention of restorations, demonstrated that out of direct-placement restorations, single surface amalgam restorations have the longest survival – 58% at ten years, and glass ionomer the shortest – at 38% at ten years.9 Large amalgam restorations, such as mesio-occlusal-distal, had shorter survival times before re-intervention than smaller (occlusal) amalgam restorations. Factors that were found to reduce restoration survival included involvement of the incisal angle in composite restorations – this resulted in a reduction in median survival of around two years - and the placement of pins in a restoration. Pin placement was found to be associated with shorter intervals to re-intervention9 and would generally be associated with a larger restoration possibly involving a cusp replacement. It may therefore be seen from the foregoing that larger restorations have a more limited longevity than smaller restorations.

Success rates of root canal fillings

Root canal treatment (RCT) is an alternative to tooth extraction when the pulp space has become infected with bacteria. RCT involves shaping and cleaning the canal space before the placement of a root filling and restoring the crown of the tooth: the clinician's skills, his/her knowledge of the prognosis and cost-effectiveness estimations will also influence the treatment decision.10 The survival of teeth which have received root canal fillings have been reported, over varying periods of time, to be between 62%11 ands 97%12. However, few papers have examined longevity of root canal fillings and/or survival of teeth when the treatment was carried out in general dental practice. In this regard, Salehrabi and Rotstein12 evaluated data from the database of the Delta Dental Insurance Data Centre located in Seattle, USA, this company being the provider of insurance for c. 14 million patients in 50 states across the USA, with the database having been maintained since 1993. Patients included in their study were those who were enrolled without a break in the dental plan from 1995 to 2002, providing a data set of 1,462,936 teeth, of which 21% were anterior teeth, 27% were premolar teeth and 52% molar teeth. At the end of the eight-year period, 97.1% of teeth were retained in the oral cavity. Most 'untoward events' were found to occur during the first three years. Lumley et al.13 showed that the survival of root filled teeth in the general dental services in England and Wales was 74% over a ten-year period before re-treatment, apical surgery or extraction.

Most recently, Ng et al.14 identified 11 prognostic factors influencing a successful outcome for root treated teeth. Success rate based on periapical health was 83% for primary RCT and 80% for re-treatment The presence of a satisfactory coronal restoration was found to be statistically a significant prognostic factor.

Ng and colleagues further reported15 that the four-year survival of root treated teeth was 95%, identifying 13 prognostic factors, including presence of a cast restoration as opposed to a temporary restoration, presence of a cast post and core restoration, proximal contact with neighbouring teeth and terminal location of the tooth.

Aim

The aim of this study was therefore to investigate teeth that received root canal fillings and subsequent direct or indirect restorations within GDS regulations in England and Wales. We examined the recorded interval to re-intervention on the crowns of teeth that had received a root canal filling and a direct or indirect restoration during the same course of treatment.

Methods

The data analysed in the present study were obtained from a large representative sample of patients treated in the GDS of England and Wales between 1991 and 2001, full details of which have already been published7 and consisted of items obtained from the payment claims submitted by GDS dentists to the Dental Practice Board (DPB) in Eastbourne, Sussex, UK.

The restoration records analysed in the study7 were further restricted to those that related to courses of treatment starting on or after the patient's eighteenth birthday in which one or more teeth were restored with a direct or indirect placement restoration and a root canal filling on the same course of treatment. A small number of teeth with tunnel restorations were excluded from the analysis. For all patients with at least one such tooth event recorded, the data were extended to include all treatment records on any of the payment schedules from January 1991 to March 2002. For each tooth treated with a restoration and root canal filling, the subsequent history of intervention on that tooth was consulted, and the next date of intervention ascertained, if any could be found in the extended data set. Thus, a data set was created of teeth that have received coronal restorations plus root fillings, with the dates of placement of the restorations and root canal fillings and the dates, if any, of re-intervention on the crown of the tooth. In the present paper, the definition of the end of the life of a restoration was taken as the date of acceptance for the next course of treatment in which the tooth received an intervention.

A technique for analysing incomplete survival data with individual dates of 'life' and 'death' was developed by Kaplan and Meier in 1958 (described in Collett, 1994).16 If it were known that all patients with restorations that had not yet received re-intervention were still attending their dentists on 1 January 2002 then Kaplan-Meier analysis could be applied directly, using 31 December 2002 as the censoring date. However, it is unrealistic to suppose that all the patients would re-attend, just as it is unrealistic to assume, as Elderton17 did, that none of them would. A technique was therefore devised by Lucarotti8 to modify Kaplan-Meier analysis to allow for the probability that a patient would eventually re-attend, dependent on the time interval from the last record of attendance by the patient to the end of the observation period (31 December 2001), together with the age of the patient. This modified Kaplan-Meier analysis has been used to quantify the distribution of survival times of teeth with restorations and root fillings.

The whole set of analyses was repeated on a second and non-overlapping random sample selected in the same way for the purpose of validating the findings from the original sample.

Results

Characteristics of the sample population

The characteristics of the sample population are as follows:

-

Just over 80,000 different adult patients were identified, of whom 46% were male and 54% female.

-

Between them they accounted for 719,009 claims for payment sent to the DPB.

-

Of the 491,404 teeth identified with direct restorations of the crown of the tooth, 22,434 teeth had root canal fillings.

-

Crowns were identified in 47,563 teeth, of which 7,639 had root canal fillings.

Directly-placed restorations

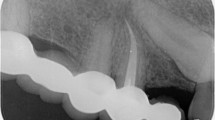

Figure 1 presents the overall data for survival of directly-placed restorations in non-root canal filled teeth and in teeth in which a root canal filling was placed in the same tooth in the same course of treatment.

Restorations in non-root canal treated teeth survived longer than those placed in root canal treated teeth on the same course of treatment regardless of tooth type (Table 2). All log-rank tests for the effect of root filling presence were significant (p <0.0001). The numbers of restorations that also had root canal fillings were as follows: incisors and canines had 5,557 out of 122,771; premolar teeth 7,965 out of 130,689; and molar teeth 8,912 out of 237,944.

Indirect restorations

Figure 2 presents the corresponding curves for survival of crowns, with the results indicating that 59% of crowns on anterior teeth, with no root filling, are present without re-intervention at ten years (Table 3). If a root canal filling is placed in the same course of treatment as the crown, survival to re-intervention at ten years is reduced to 42%. Again, all log-rank tests for the effect of presence of a root canal filling were significant (p <0.0001). The numbers of crowned teeth that also had root canal fillings were as follows: incisors and canines had 2,949 out of 19,666; premolar teeth 2,760 out of 14,197; and molar teeth 1,930 out of 13,700.

This effect is also apparent for premolar and molar teeth, although the reduction in survival time is less marked with these teeth than with incisor and canine teeth. Survival time of teeth with posts and cores was found to be less than of those teeth that had received crowns without a post and core (Fig. 3); with premolar, incisor and canine teeth having the lowest survival.

Discussion

The present study has used a large database, which was established primarily for the payment of dentists, to produce outcome data on dental restorations and to analyse the factors that influence their longevity. The data in this study were collected in such a way as to allow primarily the assessment of re-intervention on a restoration in the crown of the tooth, with the root canal filling as an additional risk factor. The study did not investigate the main determinant of success of root canal treatment, which is periapical health,14 as that information was not available to the investigators. Nevertheless the data permit comparison between teeth that received a root canal filling in the same course of treatment as a directly placed or indirect restoration and those that did not receive a canal root filling. Such re-interventions are highly relevant to outcome of treatment as leakage of bacteria into the crown of the tooth and tooth fracture can both contribute to failure.

Re-intervention on a previously restored tooth has been considered to be associated with the original restoration,5 but it is nevertheless possible that there is no causal connection – the re-intervention may have been required in response to a circumstance not related to the original restoration. The method of collection of the data does not allow recording of the reason why there was an intervention on the coronal restoration. However, it does permit comparison between teeth that have received a root canal filling and those which have not, and the influence of different restorative treatments.

Root canal fillings involve complex techniques and patient/dentist time, so they may be justified only when the benefits are assured. The results of the present study indicate that teeth with root fillings (placed during the same course of treatment as the restoration in the crown of the tooth) have less time before the next intervention than teeth that do not receive a root canal filling. This, however, should not necessarily be considered to indicate a lack of success of the root canal filling per se, although this could be the case, but is likely to be associated with other factors such as a heavily restored tooth, presence of a post, or potentially poorer aesthetics of a non-vital (discoloured) tooth. It could be argued the most likely reason for the subsequent intervention is that the dentist waited to confirm success of the RCT before the placement of a crown. The poorer outcome of restorations in teeth with root canal fillings also should not be interpreted as an indication for extraction rather than root canal filling, since the results of the present study indicate that restorations in teeth with root canal fillings all achieve a ten year rate of survival to re-intervention of 34%, and crowns on root filled teeth, while not performing as well as those on teeth with no root fillings, still provide reasonable service since 60% of crowned molar teeth with root fillings, 57% of crowned premolar teeth with root fillings and 42% of crowned incisor teeth with root fillings are still present, without any re-intervention, at ten years. Regarding the poorer survival to re-intervention of crowned anterior teeth with root canal fillings as compared with crowned posterior teeth that also receive root canal fillings, this may be considered surprising given the more amenable root canal system in these teeth and the easier access at the front of the mouth. However, it may be that it is the presence of a post, which is placed more frequently in anterior rather than posterior teeth where there is a lack of remaining tooth structure,1 which is implicated in the poorer survival of these restorations, as illustrated in Figure 3, a finding that is consistent with the work of Ng et al. published in 2011.15 Alternatively, it may be postulated that general dental practitioners elect to extract molar teeth rather than prescribing a root canal filling in situations where any difficulties are perceived with root canal morphology or accessing the tooth, and that the root canal fillings that are carried out in molar teeth are those where all the factors such as canal morphology are encouraging, thereby skewing the results. Patients may also be more reluctant to lose an anterior as opposed to a molar tooth.

No standardisation of the coronal restoration of the teeth in this study was possible, but it is likely that the majority of root canal filled teeth will also have received a coronal restoration of some sort, as part of a completed course of dental treatment. However, it is also likely that only a small proportion of the restorations, namely the resin composite restorations in anterior teeth, will have been adhesively placed. This may be, of course, of relevance, since coronal leakage has been implicated in failure of root canal fillings,18 but the overall effect of this is impossible to determine from the present data.

Few comparable data are available in the literature. Caplan and colleagues19 have recently compared survival times of root filled and non-root filled teeth in 202 patients (drawn from a large dental care programme in the Pacific Northwest in the USA), each of whom had one tooth root filled in 1987-1988 and a contralateral tooth treated but not root filled around the same time, with both teeth being followed to the end of 1994, that is, up to eight years follow-up. These workers found that root canal filled teeth had substantially worse survival than their non-root-filled counterparts. However, the overall survival of the root canal filled teeth, while poorer than the non-root-filled teeth, was greater than the outcome determined for the root canal filled teeth in the present study, with between 87% and 92% of root canal filled teeth in the US study having survived eight years. Unlike the present study, however, the subjects' teeth in the study by Caplan were mainly molar and premolar teeth, which makes the results of the two studies difficult to compare (notwithstanding the different follow-up periods). Nevertheless, it could be considered that teeth with root canal fillings placed within the GDS do not perform as well as similarly treated teeth in the study by Caplan. The factors influencing this are a matter for debate.

Ng and colleagues14 reported 83% success following root canal filling, but that refers to periapical health, which is a more rigorous criterion than tooth survival, which was the criterion used to evaluate longevity of root fillings in a study related to the present work.13 In the study by Lumley and co-workers the results indicated that 74% of root filled teeth survived for ten years. Tooth survival in the study by Ng14 was 95% at four years, which compares favourably with Salehrabi and Rotstein12 with 97.1% of teeth being retained at eight years.

In summary, there are more re-interventions on root canal treated teeth compared to non-root canal treated teeth. Approximately 35% of root canal filled anterior teeth that were restored with plastic restorations survived the ten year mark without re-intervention on the crown of the tooth, compared with 42% of crowned teeth. Fifty-seven percent of premolar teeth survived without re-intervention when restored with a crown as opposed to being restored by a plastic restoration, at 34%. Molars were similar to premolars with respect to re-intervention after root filling, and 60% with crowns did not require re-intervention at ten years as compared to 34% with plastic restorations. Therefore for all groups of root treated teeth, the placement of a crown during the same course of treatment as the placement of the root filling reduced the need for re-intervention over a ten-year period. Whether this is as a result of the cuspal coverage and the anticipated resistance to fracture that a crown may provide in a posterior tooth (albeit with more loss of tooth substance than a cuspal-coverage inlay), or whether this is due to better coronal seal of the root filling is a matter for discussion.

Conclusion

Within the limitations of this study, examination of the survival to re-intervention on the crown or the root of teeth with and without root canal fillings has indicated that teeth with root canal fillings have less time before re-intervention than teeth without root canal fillings. Teeth restored with crowns during the same course of treatment as the root canal filling was placed have a longer time before re-intervention than those restored with plastic restorations.

References

Dental Practice Board. Digest of statistics, 2004. Eastbourne: DPB, 2004.

Dental Practice Board. Digest of statistics, 2001. Eastbourne: DPB, 2001.

Dental Practice Board. Digest of statistics, 2002. Eastbourne: DPB, 2002.

Dental Practice Board. Digest of statistics, 2003. Eastbourne: DPB, 2003.

Robinson A D . The life of a filling. Br Dent J 1971; 130: 206–208.

Van Nieuwenhuysen J P, D'Hoore W, Carvalho J, Qvist V . Long-term evaluation of extensive restorations in permanent teeth. J Dent 2003; 31: 395–405.

Lucarotti P S K, Holder R L, Burke F J T . Analysis of an administrative database of half a million restorations over 11 years. J Dent 2005; 33: 791–803.

Lucarotti P S K . The life expectancy of dental restorations placed within the General Dental Services in England and Wales. University of Birmingham: PhD Thesis, 2004.

Lucarotti P S K, Holder R L, Burke F J T . Outcome of direct restorations placed within the general dental services in England and Wales (Part 1): Variation by type of restoration and re-intervention. J Dent 2005; 33: 805–815.

Reit C . Factors influencing endodontic retreatment. In Bergenholtz G, Horsted-Bindslev P, Reit C (eds) Textbook of endodontology. Oxford: Blackwell Munksgaard, 2002.

Sjogren U, Hagglund B, Sundqvist G, Wing K . Factors affecting the long-term results of endodontic treatment. J Endod 1990; 16: 498–503.

Salehrabi R, Rotstein I . Endodontic treatment outcomes in a large patient population in the USA: an epidemiological study. J Endod 2004; 30: 846–850.

Lumley P J, Lucarotti P S K, Burke F J T . Ten-year outcome of root fillings in the General Dental Services in England and Wales. Int Endod J 2008; 41: 577–585.

Ng Y L, Mann V, Gulabivala K A prospective study of the factors affecting outcome of non-surgical root canal treatment: part 1: periapical health. Int Endod J 2011; 44: 583–609.

Ng Y L, Mann V, Gulabivala K A prospective study of the factors affecting outcome of non-surgical root canal treatment: part 2: tooth survival. Int Endod J 2011; 44: 610–625.

Collett D . Modelling survival data in medical research. Chapman and Hall, 1994.

Elderton R J . The prevalence of failure of restorations: a literature review. J Dent 1976; 4: 207–210.

Saunders W P, Saunders E M . Coronal leakage as a cause of failure in root canal therapy: a review. Endod Dent Traumatol 1994; 10: 105–108.

Caplan D J, Cai J, Yin G, White A . Root canal filled versus non-root canal filled teeth: a retrospective comparison of survival times. J Public Health Dent 2005; 65: 90–96.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Dental Practice Board for the use of the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lucarotti, P., Lessani, M., Lumley, P. et al. Influence of root canal fillings on longevity of direct and indirect restorations placed within the General Dental Services in England and Wales. Br Dent J 216, E14 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.244

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.244