Key Points

-

A step by step guide to micro-surgical endodontics in practice.

-

Supports procedures with reference to the current evidence base.

-

Provides clinical tips to help clinicians achieve optimal outcomes.

Abstract

Non-surgical endodontic retreatment is the treatment of choice for endodontically treated teeth with recurrent or residual disease in the majority of cases. In some cases, surgical endodontic treatment is indicated. Successful micro-surgical endodontic treatment depends on the accuracy of diagnosis, appropriate case selection, the quality of the surgical skills, and the application of the most appropriate haemostatic agents and biomaterials. This article describes the armamentarium and technical procedures involved in performing micro-surgical endodontics to a high standard.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-surgical endodontic treatment may fail for a number of reasons.1 However, it is important to appreciate that the majority of cases fail due to the persistence or re-entry of microorganisms into the root canal system.1

Many consider maintaining their natural dentition for life as an important priority. When a tooth is of strategic importance, all viable options for maintenance of that tooth in a disease free state should be considered. A tooth may be considered of strategic importance, for example, when it is an anterior tooth in a patient with a high lip line and thin soft tissues where implant success may be difficult to predict and achieve, or when the tooth is a terminal abutment where extraction would leave the patient with an unbounded saddle and implant therapy would be contra-indicated due to lack of bone or difficulty of access. There may also be financial limitations to replacing strategically important teeth, which may render extraction of the tooth unfavourable. Often such teeth are heavily restored and endodontically treated. However, as long as the tooth is restorable (with adjunctive crown lengthening surgery where appropriate), failure of the endodontic treatment should not result in the tooth being considered untreatable. It is important to appreciate that non-surgical endodontic retreatment, to eliminate residual microorganisms and establish an adequate coronal seal, preventing re-infection, is the treatment of choice for endodontically treated teeth with recurrent disease.2

Recently published success rates for non-surgical endodontic retreatment vary from 76% to 86% depending upon the criteria used to determine success.3,4 Survival is defined as the presence of the tooth in the mouth regardless of the presence or absence of infection. Four-year survival has been stated as 93-95% and eight to ten year survival as 87%.5,6 Success is determined by the absence of clinical signs and symptoms (such as pain, swelling, tenderness to percussion, sinus, mobility) and evidence of radiographic healing. When assessing radiographic healing, studies often differentiate between strict (presence of a normal periodontal ligament space) and loose (reduction in apical radiolucency) criteria. Ng et al. (2011) reported that the success rate of non-surgical endodontic retreatment was 85% using strict criteria and 86% using loose criteria at 2-4 years.4

Systematic reviews by Del Fabbro et al. (2008) and Torbinejad et al. (2009) have compared the success rates of non-surgical and surgical endodontic treatment. These results should be interpreted cautiously because they are influenced by case selection and study inclusion criteria. Surgically treated cases appear to show higher success rates after one year. However, after 2-4 years relative success rates appear equivalent or reversed.2,7 These findings have been attributed to the slow healing of non-surgical cases and the late failures of surgical cases resulting from the slow egress of intra-radicular microorganisms persisting within the main body of the root canal system. Therefore, non-surgical endodontic retreatment should be considered before surgical endodontic treatment. This has the added advantage of potentially preventing the patient from requiring a surgical procedure.

In situations where surgical endodontic treatment is necessary, evidence suggests a modern approach to the procedure produces better outcomes. A meta-analysis compared the outcomes of traditional root end surgery (TRS) with endodontic microsurgery (EMS).8 Weighted pooled success rates were 59% (95% CI 55-63%) for TRS compared to 94% (95% CI 89-98%) for EMS, which is a statistically significant difference (P <0.0005) with EMS 1.58 time more likely to succeed than TRS.8 The absence of pre-operative pain, a satisfactory root canal filling, a periapical radiolucency less than 5 mm in diameter and an experienced operator have been identified as positive prognostic factors.2,9 Previous procedural errors and a previous surgical endodontic procedure have been identified as negative prognostic factors.2

The American Association of Endodontists guidance on surgical endodontic treatment (AAE 2010)10 and the Royal College of Surgeons of England Guidelines for Surgical Endodontics (RCS 2012)11 favour microsurgical endodontic treatment. Surgical endodontics is an umbrella term that encompasses a variety of treatments including incision and drainage, biopsy, periradicular surgery, corrective surgery (perforations, root resection, hemisection), surgical retreatment, regeneration and decompression. This paper details the technique of modern micro-surgical endodontics and the term surgical endodontics will be used to describe periradicular surgery.

Aims of Surgical Endodontics

The aim of surgical endodontic treatment is to remove any associated extra-radicular infection and foreign bodies including the removal of soft tissue lesions such as persistent apical granulomas and cysts. The root canal system must then be sealed to block the escape of any persistent intra-radicular microbes and prevent the ingress of potential nutrients from the periapical tissues.

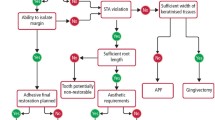

Indications for Surgical Endodontics

Decision-making should be based on best available evidence, clinical judgement and the patient's preferences.12 The available evidence indicates that surgical endodontic treatment should only be considered when the root canal system is not accessible non-surgically. Impaired or inadequate access to the apical third of the root canal system may be as a result of non-negotiable canal blockages (such as canal sclerosis, irretrievable fractured instruments in the apical third and non-negotiable ledges); internal resorption, where there is transportation of the canal to an extent that it cannot be corrected by non-surgical means; if extra-radicular microorganisms or a foreign body reaction is suspected; to repair perforations in the apical third; or if biopsy of the periapical region is required. Contrary to popular belief the presence of a post is not an absolute indication for surgical endodontic treatment as most posts (Fig. 1) can be removed safely without risk of root fracture.13 However, it is important to appreciate that there are situations where risks, costs and time considerations favour surgical root treatment even when non-surgical treatment may seem possible. For example a patient may choose not to have a large span bridge dismantled for non-surgical endodontic re-treatment of a single abutment tooth, because of the financial implications. It is important to emphasise that this approach of accepting the existing restoration is only reasonable if the tooth in question contains a satisfactory root filling and coronal seal.

Endodontic surgery is not advised for teeth with an unfavourable crown to root ratio, poor periodontal support, poor root canal obturations and inadequate coronal restorations. Additional considerations are access to the site, local anatomy and the general ability of the patient to undergo lengthy treatment. There are few absolute contraindications for surgical endodontics and the factors that merit consideration are listed in Table 1.

Pre-Operative Considerations

A good quality radiograph is required before commencing surgical endodontics. The radiograph should show all roots, the entire extent of any associated lesion, any foreign bodies, and local anatomical structures such as the inferior dental canal, mental foramen, incisive canal or maxillary sinus. Two radiographs at different angles may provide supplementary information. For large lesions where more than one tooth appears to be implicated, sensibility testing of adjacent teeth before surgery is essential. If it is necessary to carry out non-surgical endodontic treatment for adjacent non-vital teeth the need for endodontic surgery should be reconsidered after allowing time for signs of healing to become apparent. If the lesion persists with no signs of improvement surgical endodontics can be considered (Fig. 2).

Patients should be warned about the possibility of post-operative pain, swelling, bleeding, bruising, infection, sutures, gingival recession, scarring and possible treatment failure as part of the informed consent process.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) taken pre-operatively within 1-2 hours of surgery can enhance post-operative pain relief as inflammatory mediators peak at 2-4 hours post-surgery.14 The use of paracetamol and an NSAID has been shown to offer superior pain control than either drug alone. Therefore the authors recommend alternating between paracetamol and ibuprofen 4-6 hourly 'by the clock' to avoid over use of either analgesic.15 Rinsing pre-operatively with chlorhexidine gluconate (0.12%) is advocated to reduce the microbial load in the surgical field as it has been shown to eliminate 85% of bacterial flora and last four hours.16 However, there is little evidence that this reduces the incidence of post-operative infection. Antibiotics are not routinely prescribed either pre or post operatively as they are not efficacious for healthy patients.17

High success rates have been reported when surgical endodontic treatment is performed under magnification.8,18 However, it is not possible to quantify the benefits of magnification per se because it is used as part of a holistic micro-surgical approach.19 Nevertheless, magnification improves vision and it is the authors opinion that loupes, a surgical microscope or an endoscope should be used throughout the procedure. The American Association of Endodontists (AAE) and the Royal College of Surgeons on England (RCS) endorse this view.10,11

When using magnification, it is important to ensure the patient is comfortable and their neck well supported as any movement is magnified and repositioning can add to the surgical time. Mouth props and gauze can be used to aid in keeping the mandible stable for lengthy periods of time.

Peri-operative Considerations

Aseptic techniques are mandatory including surgical drapes, sterile barriers for light handles (such as autoclaved aluminium foil) and surgical gloves. Patient anxiety can be allayed by providing adequate information preoperatively, allowing sufficient time and maintaining adequate anaesthesia throughout.20

Local anaesthetic with a vasoconstrictor should be used to promote vasoconstriction in the submucosal tissues and improve visualisation of the surgical field. Care should be taken to avoid infiltration into skeletal muscle as this contains beta-2 adrenergic receptors, which cause vasodilatation in the presence of adrenaline.21 Ensuring that local anaesthesia is extended beyond the extent of the anticipated soft tissue access improves patient comfort and reduces surgical time.

Soft tissue access

A variety of soft tissue incisions have been described, the advantages and disadvantages of each are described in Table 2. A papilla preservation or papilla base flap incision is shown in Figure 3. The incision type should be selected following consideration of smile line, local anatomy (fraenal attachments, crown margins, bony eminences, width of attached gingivae), periodontal probing depths, marginal bone levels and the potential for recession following surgery. Table 3 describes the characteristic features exhibited by patients with thick and thin gingival biotypes.22 Patients with a thin gingival biotype are more susceptible to gingival recession than those with a thick gingival biotype and a submarginal incision (Fig. 4) is often most appropriate in these patients.23

A full thickness flap is required and this should be extended one or two teeth either side of the lesion(s) to allow adequate vision, atraumatic elevation and retraction. Relieving incisions should be vertical because the submucosal blood vessels run parallel to the long axis of the tooth.24 This reduces haemorrhage and maintains blood supply to the reflected flap enhancing healing. Care should be taken during tissue reflection so as not to crush the tissues, which can lead to more post operative swelling and bruising. Increasing the length of the crevicular or relieving incisions can reduce tension on the flap. The flap should be reflected using sharp elevators beginning from the vertical relieving incision at the junction of the submucosa and attached gingivae. Moving gently to dissect rather than tear reduces recession by not damaging the supracrestal root-attached fibres.25,26 Sinus tracts (Fig. 5) should be incised as close to the bone surface as possible. The tissues should be handled carefully to avoid crushing and the reflected flap should be periodically rehydrated with sterile saline to reduce flap shrinkage. If a through-and-through lesion is suspected, the reflection of palatal/lingual tissue should be avoided due to the limited visual and operative access.27 Tissue tags should be left on the bone surface, as these will aid healing. A groove prepared in the bone using a round surgical bur can allow positive location of retractor and reduce trauma to the flap.

Once access has been gained, the surgical site should be carefully examined to assess the residual bone volume and examine the root for any perforations or fracture lines. If a longitudinal root fracture is detected the tooth is unrestorable and should be extracted (Fig. 6). Careful record keeping of what was found during surgery is essential and may be beneficial for assessing reasons for failure if the surgical treatment is unsuccessful.

Hard tissue access

In many cases a bony dehiscence will be present over the root apex where granulation tissue has herniated through the labial cortical plate. In these cases access to the root end is straightforward. If this is not the case, a cavity must be prepared in the bone to access the root end. The position of the root apex should be estimated using local anatomy and the preoperative radiograph. Radiographic markers may be appropriate in some cases.

Sufficient bone must be removed to allow the surgical endodontic procedure to be completed and any thin edges of bone should be blunted to reduce the risk of sequestration. A minimum of two to three millimetres of healthy intact crestal bone should remain following cavity preparation to reduce the risk of recession and provide adequate periodontal support for the tooth (Fig. 7).21,28 Larger access cavities may be necessary for lingual or palatally curved roots, or when the buccal plate is thick to avoid a tunnel effect. Bone should be removed using either a straight surgical handpiece or a rear exhaust high speed handpiece. Air rotors are discouraged because of the potential risk of air embolism.29 Burs should be used with light pressure and adequate irrigation to reduce heat generation as this may lead to necrosis of bone.30

Once access to the root end has been achieved, the granulation tissue within the bony crypt should be removed with sharp curettes. Speedy removal of granulation tissue will reduce haemorrhage and assist vision. It is advisable to send the soft tissue removed for histopathological analysis. Sometimes there is a need to remove the root tip to gain access to the soft tissue mass or to remove the buccal root tip to gain access to the palatal root. If there is a natural fenestration of the buccal cortical plate because of root anatomy, apical root end preparation beyond this area can allow remodelling of the bone over the root (for example in the case of the buccal roots of upper first premolars).

Management of the root end

Root end resection

The apical 3 mm of the root is usually removed because 75% of teeth have canal abnormalities in the apical 3 mm of the root,31,32 canal ramifications are removed 98% of the time and accessory canals are eliminated 93% of the time.33 However, a greater length of root may be removed if there are anatomical variations, separated instruments, transposed canal apices or where access to a second, more palatally or lingually placed root is necessary. It could be argued that root end resection is unnecessary when the cause of non-healing is extraradicular, however it is only possible to determine this histologically therefore root end resection is always recommended. Methylene blue (1%) can be used to stain the periodontal ligament and apical anatomy to improve visualisation.

The root tip should be resected perpendicular to the long axis of the tooth giving a zero degree bevel. This allows for a 90 degree cavosurface margin for the root end filling and ensures that lingual anatomy is accessed. Bevelling of the root tip is not recommended, as this exposes more dentine tubules, which allow the passage of residual intra-radicular microorganisms and extra-radicular nutrients.30 If the tooth has undergone previous apical surgery, it may not be necessary or possible to remove 3 mm of the root end and still maintain a favourable crown to root ratio. Equally it may not always be possible to resect 3 mm of the root end beyond a post and still maintain adequate space for a root end filling. Following resection the root end should be smoothed as this allows better assessment of ramifications and infractions.

If the tooth has been obturated with a silver point, care should be taken to resect the root around the silver point, without cutting the silver point. This will simplify subsequent removal of the silver point.

Crypt management

Following resection of the root apex and curettage of soft tissue the bony crypt should be kept clean and dry to allow visualisation and management of the root end. Adequate haemostasis minimises surgical time, blood loss and post-operative haemorrhage and swelling.26 A local anaesthetic containing a vasoconstrictor should be used to promote haemostasis. However, when this is insufficient, a variety of adjunctive options are available. These are summarised in Table 4. Cautery/electrosurgery is not recommended because it can delay healing and cause necrosis, depending on the temperature and duration of application. Curetting the cavity and the bony walls to remove the remainder of any adhesive haemostatic agent used and causing bleeding of the bone, following placement of a root end filling, creates a blood clot which is the ideal for healing.34 An animal study assessed clinical and histological status of bone adjacent to bone wax, ferric sulphate (left for five minutess and left permanently), aluminium chloride (left for two minutes) and a combination of ferric sulphate (five minutes) and aluminium chloride (two minutess). The findings indicate a varying degree of inflammation occurs adjacent to all of the materials at 12 weeks post surgery.34 Choice of local haemostatic agents is a matter of operator preference. Biocompatibility, ease of use, efficacy, and ease of removal are likely to be the most important factors. The authors' preference is to use three cotton wool pledgets soaked in vasoconstrictor-containing local anaesthetic, applied with pressure one on top of the other and held with finger pressure for two minutes. One or two of the superficial cotton wool pledgets are then removed leaving the last one undisturbed until after root end filling. This is often adequate for timely completion of the procedure (Fig. 8).

Root end preparation

Following root end resection the apical 3 mm of the root canal system should be prepared to facilitate an adequate apical seal.35 The preparation must follow the anatomical canal space and develop adequate retention form. If there are two canals in a root, at the 4 mm level there will be a partial or complete isthmus 100% of the time.36,37 When there are two root canals within a root the isthmus between the canals should also be prepared to a depth of 3 mm as there are likely to be communications in this area.36,37 Therefore, a minimum of 6 mm of root length apical to a post is required for satisfactory root resection and cavity preparation.

Ultrasonic instruments are preferred for root end cavity preparation because they are small, easy to manoeuvre and allow deeper preparation of the root end than a round bur (Fig. 9). They permit cavity preparation perpendicular to the resected toot end. Ultrasonic tips are available in a variety of sizes and angulations (Fig. 10). A number of studies have shown higher success with ultrasonic preparation compared to preparation with burs.38,39,40 Some have suggested that the use of ultrasonics causes cracks within the root surface, however studies on cadavers showed no increase in cracks with the use of ultrasonics as the periodontal ligament is thought to absorb the stresses.41 Ultrasonic tips can be used without irrigation to improve visualisation. However, when irrigant is not used, the authors recommend that the tips be used intermittently on a low power setting to prevent the risk of overheating and extend the lifetime of these tips.

Root end conditioning

No evidence exists to support the assertion that smooth root ends promote better healing however a smooth surface allows better assessment of ramifications and cracks. Burs that produce a smooth end usually produce less vibration and may be more comfortable for the patient. Removing the smear layer by conditioning provides a surface that may be more conducive to mechanical adhesion as well as the cellular mechanisms for growth and attachment as it exposes the collagen matrix and retained biologically active components like growth factors.42 Agents such as ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), citric acid and tetracycline have been used in animal studies, however their benefit in humans has not been proven.30

A Stropko irrigator can be safely used with air only or air and sterile water to clear the retrograde cavity preparation (Fig. 11). A 25 gauge needle can be used, bent for better control of the spray. The air pressure should be reduced to 4-7 lbs/in2 and water pressure should similarly be reduced.21

Root end fillings

Once the root is resected and cavity prepared, the root end is ready to be sealed. A number of materials can be used as root end filling materials, their advantages and disadvantages are outlined in Table 5. Increasing the depth of the apical filling reduces leakage. The preparation depth needed for an adequate seal under ideal conditions increases with increasing bevel therefore the minimum depth needed for a 0° bevel is 1 mm, that for a 30° bevel is 2.1 mm and for a 45° bevel is 2.5 mm.43 An apical filling of 3 mm is recommended.

Torabinejad et al. (1995) determined the time needed for Staphylococcus epidermidis to penetrate a 3 mm thickness of amalgam, Super-EBA, Intermediate Restorative Material (IRM), or mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) as root-end filling materials using 56 single-rooted extracted human teeth. MTA leaked significantly less than other root-end filling materials maintained under test conditions for 90 days in this experiment.35 However, an randomised controlled trial by Chong et al. (2003) has suggested that MTA is not significantly superior to IRM.44 Gondim et al. (2003) investigated marginal adaptation of root end fillings and found that MTA adapted better to cavity margins with or without finishing procedures.45 MTA has been shown to support almost complete regeneration of the apical periodontal tissues with a new periodontal ligament.46 The placement of MTA is facilitated by adequate haemostasis and the use of an MTA carrier or a Lee block. Ultrasonic activation can be used to achieve a homogenous apical seal without voids (Fig. 12).

New bioactive materials such as Biodentine (Septodont, Saint-Maurdes Fosses, France) have recently been marketed as materials with dentine-like properties that can be used as root end filling materials. Purported advantages include biocompatibility, regenerative potential, antimicrobial properties, ease of use and long term sealing ability. Currently there are no published clinical outcome data on the effect of using Biodentine as root end filling materials in microsurgical endodontics.

Closure of surgical site:

Prior to closing the surgical site, a radiograph should be taken to ascertain the status of the root end filling and ensure all foreign objects have been removed. The crypt should be thoroughly irrigated with saline to remove any haemostatic agents and packing materials. The crypt should then be scraped with a sharp curette to encouraging bleeding and the formation of a blood clot.34 Bony crypts are usually filled with blood clots and natural bony infill, to varying degrees, occurs. Some have suggested the use of guided tissue regeneration for preventing soft tissue growth into the bony crypt by using a membrane for selective repopulation. This has mainly been for cases where there is a through-and-through perforation of the bone or where apical migration of the epithelium is a potential problem.47 No additional beneficial effect on healing is seen where there is a residual buccal cortical plate over the remainder of the root.48

The flap should be carefully replaced and sutured without tension as tension may lead to necrosis at the incision site with subsequent scarring or recession.21 Small diameter sutures (5/0 or smaller) are recommended as they have smaller needles, cause less trauma and lead to thread breaking rather than tissue tearing.49 Non-resorbable monofilament sutures are recommended, as they are less supportive of bacterial growth.50 Gentle compression of the flap for one-minute post closure ensures fibrin adhesion and may prevent haematoma development.30 Post-operative antibiotics are not routinely prescribed unless surgery has been extraordinarily long or the patient is immunocompromised.11 Removal of sutures at three days post operatively is recommended as epithelial bridging and collagen crosslinking is thought to happen within 21-28 hours.25

Post-operative Considerations

As with most oral surgical procedures, the patient should be advised to take simple analgesia, reduce the swelling and prevent further swelling by using ice packs for 24 to 48 hours, maintain good oral hygiene and use chlorhexidine gluconate (0.12%) mouthwash twice daily for a minimum of three days post operatively and warm saltwater mouth washes 4-5 times daily for seven days.

Review and assessing success of surgical endodontic treatment

Sutures should be removed at three days post surgery and if histopathological results are available the patient should be informed of the findings. If healing is uneventful at this stage, the patient can be reassessed at one-year following surgical treatment.51 Clinical and radiographic examination is necessary to determine the extent of healing. If the patient returns with signs of non-healing and frank infection, the cause of failure needs to be established. Repeated treatment without diagnosis of the cause of failure is unlikely to resolve the condition.

The options for failed surgical endodontic treatment are to consider non-surgical endodontic re-treatment, surgical re-treatment or extraction (± prosthetic replacement). The outcome of surgical re-treatment is lower with 36% being successful, 26% having uncertain healing and 38% having failed at one-year.52 Gagliani et al. (2005) have shown higher healing rates for re-surgery with 59% being successful, 17% having uncertain healing and 23% having failed at one to five years.53

Conclusion

Non-surgical endodontic retreatment is the treatment of choice for endodontically treated teeth with recurrent or residual disease, however, surgical endodontic treatment is appropriate in selected cases. Clinicians require a thorough understanding of this treatment procedure and should appreciate the importance and rationale of the different stages detailed above. Optimal outcomes for surgical endodontic treatment can only be achieved if the diagnosis is accurate, appropriate cases are selected and the procedure is completed to a high standard.

References

Nair P N . On the causes of persistent apical periodontitis: a review. Int Endod J 2006; 39: 249–281.

Torabinejad M, Corr R, Handysides R et al. Outcomes of non-surgical retreatment and endodontic surgery: a systematic review. J Endod 2009; 35: 930–937.

Ng YL, Mann V, Gulabivala K . Outcome of secondary root canal treatment: a systematic review of the literature. Int Endod J 2008; 41: 1026–1046.

Ng YL, Mann V, Gulabivala K . A prospective study of the factors affecting outcomes of non-surgical root canal treatment: part 1: periapical health. Int Endod J 2011a; 44: 583–609.

Ng YL, Mann V, Gulabivala K . Tooth survival following non-surgical root canal treatment: a systematic review of the literature. Int Endod J 2010; 43: 171–189.

Ng YL, Mann V, Gulabivala K . A prospective study of the factors affecting outcomes of non-surgical root canal treatment: part 2: Tooth survival. Int Endod J 2011b; 44: 610–625.

Del Fabbro M, Taschieri S, Testori T, Francetti L, Weinstein R L . Surgical vs non-surgical endodontic re-treatment for periradicular lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; 18: CD005511.

Setzer F C, Shah S B, Kohli M R, Karabucak B, Kim S . Outcome of endodontic surgery: a meta-analysis of the literature part 1: Comparison of traditional root-end surgery and endodontic microsurgery. J Endod 2010; 36: 1757–1765.

von Arx T, Penarrocha M, Jensen S . Prognostic factors in apical surgery with root-end filling: a meta analysis. J Endod 2010; 36: 957–973.

American Association of Endodontists. Endodontics Colleagues for Excellence: Contemporary endodontic microsurgery: procedural advancements and treatment planning considerations. 2010. Available at: www.aae.org/uploadedfiles/publications_and_research/endodontics_colleagues _for_excellence_newsletter/ecfefall2010final.pdf (accessed 15 November 2013).

Evans G E, Bishop K, Renton T . Royal College of Surgeons guidelines for surgical endodontics. 2012.

Haynes, R B, Devereaux P, Guyatt G H . Clinical Expertise in the Era of Evidence Based Medicine and Patient Choice. ACP Journal Club 2002; 136: A11A14.

Abbott P V . Incidence of root fractures and methods used for post removal. Int Endod J 2002; 35: 63–67.

Roszkowski M T, Swift J Q, Hargreaves K M . Effects of NSAID administration on tissue levels of Immunoreactive prostaglandin E2, leukotriene B4 and (s)-flurbiprofen following extraction of impacted third molars. Pain 1997; 73: 339–346.

Ong C K S, Seymour R A, Lirk P, Merry A F . Combining paracetamol (acetaminophen) with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a qualitative systematic review of analgesic efficacy for acute postoperative pain. Anesth Analg 2010; 110: 1170–1179.

Balbuena L, Stambaugh K I, Ramirez S G, Yeager C . Effects of topical oral antiseptic rinses on bacterial counts of saliva in healthy human subjects. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998; 118: 625–629.

Longman L P, Preston A J, Martin M V, Wilson N H F . Endodontics in the adult patient: the role of antibiotics. J Dent 2000; 28: 539–548.

Tsesis I, Faivishevsky V, Kfir A et al. Outcome of surgical endodontic treatment performed by a modern technique: a meta-analysis of literature. J Endod 2009; 35: 1505–1511.

Del Fabbro M, Taschieri S . Endodontic therapy using magnification devices: a systematic review. J Dent 2010; 38: 269–275.

Weiner R N, Forgione A G, Weiner L K . Survey examines patients' fear of dental anxiety treatment. J Mass Dent Soc 1998; 47: 16–21, 36.

Stropko J J . Vol III Chapter 34 Micro-surgical endodontics. In Castellucci A. Endodontics. pp 1076–1145. Florence, Italy, 2009.

Sclar A G . Strategies for management of single-tooth extraction sites in aesthetic implant therapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004; 62: 90–105.

von Arx T, Salvi G E, Janner S, Jensen S S . Gingival recession following apical surgery in the aesthetic zone: a clinical study with 70 cases. Eur J Esthet Dent. 2009; 4: 28–45.

Macphee T C, Cowley G . Essentials of periodontology and periodontics, 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific, 1981.

Harrison J W, Jurosky K A . Wound healing in the tissues of the periodontium following periradicular surgery. I. The incisional wound. J Endod 1991; 12: 425.

Gutmann J L, Harrison J W . Surgical endodontics. St Louis: Ishiyaku EuroAmerica, 1994.

Ingle J I, Bakland L K . Endodontics, 5th ed. London: BC Decker Inc, 2002.

Song M, Kim S G, Shin S-J, Kim H-C, Kim E . The influence of bone tissue deficiency on the outcome of endodontic microsurgery: a prospective study. J Endod 2013; 39: 1341–1345.

McKenzie W S, Rosenberg M . Iatrogenic subcutaneous emphysema of dental and surgical origin: a literature review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 67: 1265–1268.

Cohen S, Hargreaves K M . Pathways of the pulp, 10th ed. Mosby Elsevier, 2011.

De Deus Q D . Frequency, location and direction of the lateral, secondary and accessory canals. J Endod 1975; 1: 361–366.

Seltzer S, Soltanoff W, Bender I B, Ziontz M . Biologic aspects of endodontics. Part 1: histological observations of the anatomy and morphology of root apices and surroundings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1996; 22: 375.

Kim S, Pecora G, Rubenstein R, Dorscher-Kim J . Colour atlas of microsurgery in endodontics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2001.

von Arx T, Jensen S S, Hänni S, Schenk R K . Haemostatic agents used in periradicular surgery: an experimental study of their efficacy and tissue reactions. Int Endod J 2006; 39: 800–806.

Torabinejad M, Rastegar A F, Kettering J D, Pitt Ford T R . Bacterial leakage of mineral trioxide aggregate as a root-end filling material. J Endod 1995; 21: 109–112.

Teixeira F B, Sano C L, Gomez B P, Zara A A, Ferraz C C, Souza-Filho F J. A preliminary in vitro study of the incidence and position of the root canal isthmus in maxillary and mandibular first molars. Int Endod J 2003; 36: 276–280.

Weller R N, Niemczyk S P, Kim S . Incidence and position of the canal isthmus. Part 1: mesiobuccal root of the maxillary first molar. J Endod 1995; 21: 380–383.

Shearer J, McManners J . Comparison between the use of an ultrasonic tip and a microhead handpiece in periradicular surgery: a prospective randomised trial. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 47: 386–388.

De Lange J, Putters T, Baas E M et al. Ultrasonic root-end preparation in apical surgery: a prospective randomised study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007; 104: 841–845.

Vallecillo Capilla M, Muñoz Soto E, Reyes Botella C, Prados Sáchez E, Olmedo Gaya M V . Periapical surgery of 29 teeth. A comparison of conventional technique, microsaw and ultrasound. Med Oral 2002; 7: 49–49, 50–53.

Kim S, Kratchman S . Modern endodontic surgery concepts and practice: a review. J Endod 2006; 32: 601–623.

Galler K M, D'Souza R N, Federlin M et al. Dentine conditioning codetermines cell fate in regenerative endodontics. J Endod 2011; 37: 1536–1541.

Gilheany P A, Figdor D, Tyas M J . Apical dentine permeability and microleakage associated with root end resection and retrograde filling. J Endod 1994; 20: 22–26.

Chong B S, Pitt Ford T R, Hudson M B . A prospective clinical study of MTA and IRM when used as a root end filling material in endodontic surgery. Int Endod J 2003; 36: 520–526.

Gondim E Jr, Zaia A A, Gomes B P F A, Ferraz C C, Teixeira F B, Souza-Filho F J. Investigation of the marginal adaptation of root-end filling materials in root-end cavities prepared with ultrasonic tips. Int Endod J 2003; 36: 491–499.

Regan J D, Gutmann J L, Witherspoon D E . Comparison of Diaket and MTA when used as root-end filling materials to support regeneration of the periradicular tissues. Int Endod J 2002; 35: 840–847.

Dietrich T, Zunker P, Diertich D, Bernimoulin J P . Periapical and periodontal healing after osseous grafting and guided tissue regeneration treatment of apicomarginal defects in periradicular surgery; results after 12 months. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003; 95: 474–482.

Garrett K, Kerr M, Hartwell G, O'Sullivan S, Mayer P . The effect of a bioresorbable matrix barrier in endodontic surgery on the rate of periapical healing: an in vivo study. J Endod 2002; 28: 503–506.

Burkhardt R, Preiss A, Joss A, Lang N P . Influence of suture tension to the tearing characteristics of the soft tissues: an in vitro experiment. Clin Oral Implants Res 2008; 19: 314–319.

Banche G, Roana J, Mandras N et al. Microbial adherence on various intraoral suture materials in patients undergoing dental surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007; 65: 1503–1507.

European Society of Endodontology. Quality Guidelines for endodontic treatment: consensus report of the European Society of Endodontology. Int Endod J 2006; 39: 921–930.

Peterson J, Gutmann J L . The outcome of endodontic re-surgery: a systematic review. Int Endod J 2001; 34: 169–175.

Gagliani M M, Gorni, F G M, Strohmenger L . Periapical. Resurgery versus periapical surgery: a 5-year longitudinal comparison. Int Endod J 2005; 38: 320–327.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eliyas, S., Vere, J., Ali, Z. et al. Micro-surgical endodontics. Br Dent J 216, 169–177 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.142

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.142

This article is cited by

-

Surgical endodontics: are the guidelines being followed? A pilot survey

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

Pre- and postoperative management techniques. Part 3: Before and after — Endodontic surgery

British Dental Journal (2015)