Key Points

-

Explores the clinical activity and views of hygienists and therapists regarding autonomous working.

-

Details how these practitioners are currently undertaking tasks relating to assessment and treatment planning with a considerable degree of autonomy.

-

All three groups possess a high level of confidence in their ability to conduct a wide range of clinical activities without direct referral from a dentist.

Abstract

Objectives To investigate autonomous working among singly and dually qualified dental hygienists and therapists in UK primary care. Earlier studies and policy papers suggest that greater autonomy for these groups may be a desirable workforce planning goal.

Methods UK-wide postal surveys of hygienists, hygienist-therapists and therapists. Respondents were asked whether they undertook 15 clinical activities on their own initiative, how comfortable they would feel undertaking such clinical activities if referral from a dentist were not required, and how they perceived dentists' reactions.

Results Overall response rate was 65% (n = 150 hygienists, 183 hygienist-therapists and 152 therapists). Over 80% of hygienists and hygienist-therapists reported undertaking BPEs, history-taking, pocket charting, mucosal examinations and recall interval planning autonomously. Similarly high proportions of hygienist-therapists and therapists reported giving local analgesia and choosing restorative materials autonomously. However, fewer than 50% of all three groups said they undertook dental charting, fissure sealing, resin restorations, taking radiographs, and tooth whitening autonomously. While confidence in undertaking such activities without a dentist's referral was generally high, it was lower in respect to mucosal examinations, identifying suspicious lesions, interpreting radiographs, tooth whitening, and (except for singly qualified dental therapists) diagnosing caries.

Conclusions Results suggest high levels of experience and confidence in their ability to work autonomously across a wide range of investigative activities, treatment decision-making and treatment planning. The exceptions to this pattern are appropriate to the different clinical remit of these groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Policy documents published in the last ten years have stressed the need to widen the contribution of members of the dental team to providing dental care. In Scotland, the 2005 Action plan for improving oral health and modernising NHS dental services in Scotland set the policy direction for dental services and included new investment in NHS workforce development in Scotland.1 The report saw the wide clinical remit of dental hygienists and therapists as one way of increasing the amount of dental care delivered, noting that a therapist can increase a dentist's output by 45% and a hygienist can increase daily output by 33%. The Action Plan promised to 'use to the full the flexibilities currently available for the use of (dental care professionals) and take advantage of the(ir) proposed extended role'. An earlier report on dental services in England adopted a similar policy aim of maximising the contribution of dental therapists and hygienists.2 However, neither document proposed changing the requirement for hygienists and therapists to work under the direction of a registered dentist. This situation is in contrast to developments in other fields of healthcare such as the availability of direct access to physiotherapists and practice nurses and nurse-led triage arrangements.

There is evidence that the UK has lagged behind in the move towards wider clinical autonomy within the dental team. Johnson, in an international longitudinal survey of national dental hygienists' associations conducted between 1987 and 2006, reports an increase in scope of practice and professional autonomy including, for many countries, a decline in mandatory work supervision and a slight increase in independent practice.3 A review by O'Neill et al. reports that dental hygienists in New Zealand favoured full professional status for dental hygiene through their support for self-regulation and autonomy. The authors conclude that the most prudent use of healthcare funds requires the full utilisation of all members of the dental team.4 New Zealand has subsequently introduced a high level of autonomous working among dental hygienists, including examinations and formulation of treatment plans. The potential cost savings of independent working have also been highlighted by recent work in the UK.5

However, the situation regarding the dental team in the UK may change in the near future. Following a public consultation in 2009, HM Government accepted the recommendation of the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency that dental hygienists and therapists be allowed to choose and administer local anaesthetics independently and to issue named medicines directly to patients. The relevant Statutory Instrument cites avoiding unnecessary delays to patient care and better use of dental skill mix as justification.6 Concurrently the General Dental Council (GDC) Standards Committee considered a proposal to remove the requirement for patients to be seen by a dentist before receiving treatment from a hygienist and/or therapist, thus enabling direct access to such dental care.7 The situation is complicated by the fact that in the UK there are three district groups of these dental care professionals: dental hygienists, numbering approximately 5,600 (according to the GDC Register of DCPs) and providing mainly periodontal and preventive care; dually qualified hygienist-therapists (approximately 1,100 in number), whose remit also includes a wide range of restorative work; and approximately 200 singly qualified therapists (whose training programme ceased some 20 years ago), who traditionally worked mainly in community clinics and with children. This paper deals with all three groups.

The present contradictory situation is summed up by the following description of the dental therapist's role: 'A registered dentist must examine the patient and indicate clearly in writing the course of treatment that the dental therapist needs to carry out'. 'As clinical decisions will ultimately be based on the needs of the individual patient, the dental therapist will have autonomy over the way that the treatment plan is undertaken. This will include the choice of instruments and materials to be used, which requires expert knowledge and skills'.8

There has also been some ambiguity over the clinical remit of dental hygienists and therapists. In June 2006 the GDC published new standards in their document Principles of Dental Team Working, which stated that DCPs could carry out any treatment that they were trained and competent to do.9 This absence of clinical remit was ended in 2009 when the GDC published Scope of Practice.10 This document defined the extent of and exclusions from each dental team member's clinical remit, including potential additions to that remit following specific training. The intention was to protect the best interests of patients by developing greater clarity regarding the skills expected of a newly qualified and registered professional, skills they can develop, and skills reserved for other groups.

Public opposition does not appear to be an obstacle to autonomous working. Over 20 years ago, a study of ten experimental independent dental hygiene practices in California, USA, found that they consistently attracted new patients and that their patients expressed high levels of satisfaction with care received. The study concluded that such practices might increase access to care without increasing the risk of inappropriate referral (or non-referral) of patients to dentists.11 In 2000 a Canadian telephone survey of 1,202 adults found public support for dental hygienists gaining independent practice, and that the public trusted the level of care provided by the dental hygiene profession.12 In a 2010 UK study, Sun et al. report that of 431 patients, those attending appointments with therapists were found to have a significantly higher level of overall satisfaction than those attending appointments with dentists.13

A recent large-scale survey examined the nature of clinical work undertaken by singly and dually qualified therapists in the UK and their attitudes towards teamwork.14,15 While 96% of therapists in that study agreed with the statement 'I feel part of the clinical team', 55% felt that they could do more extensive work if it was referred to them. Many felt this was due to dentists' lack of awareness or confidence in their abilities. Other studies have concluded that poor knowledge and negative attitudes held by dentists and dental students may restrict the development of the dental team.16,17,18 No UK studies have directly addressed the issue of how much professional autonomy is achieved, in which areas (assessment, treatment, treatment planning), whether level of autonomy is related to qualification, type of service or years in service, or how DCPs feel about greater autonomy.

The objective of this study was to survey representative samples of dental hygienists, therapists and dually qualified hygienist-therapists working in dental primary care in the UK in order to obtain information concerning their current level of autonomous working, factors which may be associated with such autonomy, and their attitudes towards greater autonomy in their clinical work. Professional autonomy may be defined as independence and self-direction, especially in making decisions, enabling professionals to exercise judgment as they see fit during the performance of their jobs.

Materials and methods

Separate random sample surveys of hygienists and hygienist-therapists were conducted. Because of their small number (227), 100% of singly qualified therapists were surveyed. The General Dental Council (GDC) register of dental care professionals was used as the sampling frame, being both up-to-date and comprehensive. Statistical advice indicated that samples of 300 hygienists and 300 hygienist-therapists would be sufficient to achieve an error rate of 5% at 90% confidence level, given an anticipated response rate of 66%. The three professional groups were identified by their self-reported qualification on the GDC register. A questionnaire was developed, piloted and distributed by post in April-May 2009, followed by two reminders and a second questionnaire in June 2009. Mailing procedure, questionnaire design, wording of questions, and content of cover letter and reminders followed recommended practice for health service-related surveys.19 This paper follows the recommendations of the STROBE statement on the reporting of observational studies.20

The questionnaire covered the following areas: qualifications held and institution attended; current employment and case load; the nature of referrals from dentists; clinical and treatment planning activities undertaken; nature and adequacy of training; soft tissue lesions; CPD activities; future changes to remit and referral; patient and dentist attitudes; job satisfaction; and amount of, and attitudes towards, autonomous working. Current autonomous working was investigated by asking respondents whether they undertook 15 clinical activities (see Figs 1,2,3) only when the dentist requested, when they themselves decided it was needed, in both circumstances, or not at all (not applicable). Responses 'When I decide it's needed' and 'A combination of both of these' were scored 1 and summed across the 15 items to produce a numerical measure of autonomous working. Scores for hygienists were adjusted to take account of the fact that two items (preventive restorative restorations and choosing restorative materials) were outside their remit. Scores for all three groups were standardised to a range of 0 to 100. Variables reflecting demographic and employment characteristics were entered as predictors of autonomy scores in separate multiple regression analyses for the three groups. These included a measure of dentists' recognition of their work (the sum of respondents' five-point ratings of dentists' recognition of DCPs' clinical remit, quality of work and qualification: range 3-15: Chronbach's alpha = 0.79). We also investigated whether greater autonomy was associated with a greater breadth of clinical activity, or conversely whether DCPs tended to work autonomously in a restricted range of activities. Attitudes towards greater autonomy were investigated by asking how comfortable respondents would feel undertaking 15 assessment, treatment and treatment planning activities if regulations permitted that referral from a dentist was not required. Data were analysed using SPPS version 17.

Results

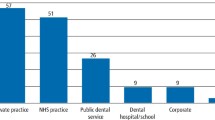

The overall response rate was 65% (533 of 826). Group response rates were 60% (181 of 300) for hygienists, 60% (180 of 300) for hygienist-therapists, and 76% (172 of 226) for singly qualified therapists. Five respondents sampled as hygienists reported also holding a therapy qualification, and two therapists reported having a hygiene qualification. These individuals were reclassified as dually qualified. Respondents not currently working in either the salaried or general dental services (a total of 48) are excluded from this paper, giving final figures of 150 hygienists, 183 hygienist-therapists and 152 singly qualified therapists. Table 1 summarises the background and employment characteristics of the three groups. Hygienists worked almost exclusively in general dental practice, mainly seeing adult, non-NHS patients. Dually qualified hygienist-therapists were on average younger, included a few more males, worked the longest hours and saw the most patients. Singly qualified therapists were often close to retirement age, working mainly in the salaried service treating NHS patients, including a high proportion of children.

Autonomous working

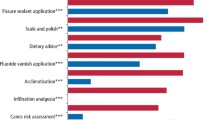

Figures 1,2,3 show proportions reporting autonomous working relating to assessment, treatment, and diagnosis and treatment planning. (Note: two restorative activities shown in Figure 2 do not apply to hygienists). For hygienists and hygienist-therapists, autonomous working was most common with regard to assessment (but not dental charting). Planning recall intervals, diagnosing periodontal disease and giving local analgesia was commonly undertaken autonomously in all three groups. For therapists and hygienist-therapists, choosing restorative materials was also commonly undertaken autonomously. Fewer than 50% of all three groups undertook dental charting, fissure sealing, resin restorations, taking radiographs, and tooth whitening autonomously.

Scores on the measure of autonomous working were 52.9 (SD 18.2, n = 150) for hygienists, 55.4 (SD 16.6, n = 183) for hygienist-therapists, and 47.3 (SD 23.5, n = 152) for therapists. Table 2 gives the results of the multiple regression analyses of predictors of greater autonomy. Statistically significant associations are shown in bold.

For singly qualified therapists, greater workload (number of patients seen per week) predicted greater autonomy. For dually qualified hygienist-therapists, working outside of England (that is, where GDPs work to a different contract) predicted greater autonomy.

The question of whether greater autonomous working was associated with a wider range of activities was investigated by correlating the number of activities undertaken with the mean level of autonomy across the activities concerned. For hygienists and hygienist-therapists, no association was found (r = 0.02, ns, n = 152 and r = -0.04, ns, n = 181 respectively), while a moderate positive association was found for therapists (r = 0.27, p = 0.001, n = 150), that is, therapists with a higher mean level of autonomy for each activity also tended to undertake a wider range of activities.

Attitudes towards working without dentist's referral

Figures 4,5,6 show the proportion in each group who said they would be comfortable undertaking each activity without referral from a dentist if regulations allowed such referrals. Note that the activities shown mirror those in Figures 1,2,3, but with some rewording to reflect clinical decision making rather than treatment. Confidence regarding their ability to undertake these activities without referral was generally high, particularly among dually qualified hygienist-therapists. Activities which were seen as more worrying without a dentist's referral were mucosal examinations, interpreting radiographs, tooth whitening, and, except for singly qualified therapists, diagnosing caries. The only activity which the majority of all three groups said they would feel uncomfortable undertaking autonomously was the identification of suspicious lesions. In a separate question respondents were asked what they would do if they found a soft tissue lesion that they suspected might be malignant. Between 95% and 98% said they would ask the dentist to examine immediately.

Respondents were asked what they thought would be the view of dentists they worked with if they were able to see patients directly without referral and treatment plan from a dentist. Table 3 shows their responses.

The responses suggest that the majority of all three groups of DCPs expected a favourable view of direct referral from at least some of the dentists they worked with, and 15% or fewer expected a generally unfavourable response. Asked to comment on the possibility of direct access, 223 (46%) did so. Figure 7 gives a number of representative examples of these comments.

Discussion

The use of the GDC register of DCPs as a sampling frame has the merit of including all individuals of interest, as all DCPs must maintain their registration on an annual basis in order to practise. However, it is likely that not all registrants are currently practising, as some may maintain their GDC registration during periods when they are not practising in order to avoid paying re-registration fees. In addition, changes of address in the 12 months post registration may not be notified until renewal each summer. In these circumstances, it is felt that the response rate of 65% is satisfactory. Respondents are representative of this workforce in terms of geographical distribution, gender, skill mix, age and employment status.21

The general pattern regarding autonomous clinical activity (Figs 1,2,3) is of singly qualified therapists undertaking less autonomous assessment and less treatment planning than either hygienists or hygienist-therapists, On the other hand, therapists more frequently report undertaking fissure sealing and preventive resin restorations autonomously, probably as a result of their greater number of child patients. Within each group the level of autonomous working defined in this way varied considerably. No significant predictors of greater autonomy were identified, with the exceptions of higher workload among singly qualified therapists, and working outside England for hygienist-therapists. For hygienists and hygienist-therapists there was no evidence that those who specialised in relatively few clinical activities achieved a higher level of autonomy in those activities. For therapists, a wider range of activities was associated with a higher level of autonomy within those activities.

The study also found that, in general, all three groups would feel comfortable undertaking clinical activities without a dentist's referral. This suggests a high level of confidence across a wide range of investigative activities, treatment decision-making and treatment planning. One exception to this was identification of suspicious lesions, where the vast majority said they would immediately seek the dentist's opinion. The issue of opportunistic screening in primary dental care has been the subject of considerable attention, with dentists' own ability to diagnose and refer effectively questioned.22 DCPs in the study expected relatively limited opposition from dentists in the event of direct access becoming legal. The nature of the financial structure of the General Dental Service, with dentistry largely operated as a business, may be one reason why dentistry lags behind medicine in its adoption of widening access to primary care team members.

The UK dental hygienist and therapist workforce is approaching 7,000, representing one for every five high street dentists and every 9,000 of the general population, making a growing contribution to primary dental care in the UK. A related paper has reported on the clinical activity of dually qualified hygienist therapists in this survey, and found a strong link between the widespread underuse of therapy skills and job satisfaction. The authors concluded that underuse of therapy skills in this highly trained group of practitioners raised the danger of deskilling, demoralisation and poor staff retention.23 The present study has confirmed that hygienist-therapists have a high level of experience and confidence in undertaking dental care in both the general dental and salaried service without the requirement for direction and formal supervision from dentists, and that these attributes are also shared by hygienists and singly qualified therapists. The NHS Workforce Review Team 2009 recommended expansion of the numbers of dually qualified hygienist-therapists as a means of increasing the level and amount of primary dental care.21 The British Dental Council Customer Advice and Information Team report frequent enquires from patients aggrieved that they have to see the dentist before seeing the hygienist.7 The 2003 Office of Fair Trading report The private dentistry market in the UK24 recommended ending restrictions on DCPs so that they were free to supply their services directly to consumers, as this would potentially expand the availability of dental services and offer greater choice to consumers and those working in the profession. Such developments, together with the possible support of the GDC Standards Committee for the ending of the requirement for patients to be referred by a dentist, suggest it may only be a matter of time before their potential for professional autonomy is more fully realised.

References

Scottish Executive Health Department. An action plan for improving oral health and modernising NHS dental services in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive, 2005.

Department of Health. Modernising NHS dentistry – implementing the NHS plan. London: Department of Health, 2000.

Johnson P M. International profiles of dental hygiene 1987 to 2006: a 21-nation comparative study. Int Dent J. 2009; 59: 63–77.

Gillis M V, Praker M E . The professional socialization of dental hygienists: from dental auxiliary to professional colleague. NDAJ 1996; 47: 7–13.

Williams S A, Bradley S, Godson J H, Csikar J I, Rowbotham J S . Dental therapy in the United Kingdom: part 3. Financial aspects of current working practices. Br Dent J 2009; 207: 477–483.

HM Government. The Medicines for Human Use (Miscellaneous Amendments) Order 2010. London: The Stationery Office, 2010.

General Dental Council. General Dental Council Standards Committee meeting 27 January 2010. http://www.gdc-uk.org/NR/rdonlyres/B5ADBE21-D5AF-45F2-A621-D06909DD021B/0/EnclosureDDirectAccess.doc. Accessed 7 July 2010.

NHS Careers. Dental therapist. http://www.nhscareers.nhs.uk/details/Default.aspx?Id=504. Accessed 17 February 2011.

General Dental Council. Principles of dental team working. London: General Dental Council, 2006.

General Dental Council. Scope of practice. London: General Dental Council, 2009.

Perry D A, Freed J R, Kushman J E . Characteristics of patients seeking care from independent dental hygienists practices. J Public Health Dent 1997; 57: 76–81.

Edgington E, Pimlott J . Public attitudes of independent dental hygiene practice. J Dent Hyg 2000; 74: 261–270.

Sun N, Burnside G, Harris R . Patient satisfaction with care by dental therapists. Br Dent J 2010; 208: E9.

Godson J H, Williams S A, Csikar J I, Bradley S, Rowbotham J S . Dental therapy in the United Kingdom: part 2. A survey of reported working practices. Br Dent J 2009; 207: 417–423.

Csikar J I, Bradley S, Williams S A, Godson J H, Rowbotham J S . Dental therapy in the United Kingdom: part 4. Teamwork – is it working for dental therapists? Br Dent J 2009; 207: 529–536.

Ross M K, Ibbetson R J, Turner S . The acceptability of dually-qualified dental hygienist-therapists to general dental practitioners in South-East Scotland. Br Dent J 2007; 202: E8.

Ross M K, Turner S, Ibbetson R J . The impact of teamworking on the knowledge and attitudes of final year dental students. Br Dent J 2009; 206: 163–167.

Sprod A, Boyles J . The workforce of professionals complementary to dentistry in the general dental services: a survey of general dental practices in the South West. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 389–397.

McColl E, Jacoby A, Thomas L et al. Design and use of questionnaires: a review of best practice applicable to surveys of health service staff and patients. Health Technol Assess 2001; 5: 1–256.

von Elm E, Altman D G, Egger M et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008 Apr; 61: 344–349.

NHS Workforce Review Team. Workforce summary – dental therapists and dental hygienists 2008 – England only. London: Centre for Workforce Intelligence, 2008.

Brocklehurst P R, Baker S R, Speight P M . Primary care clinicians and the detection and referral of potentially malignant disorders in the mouth: a summary of the current evidence. Prim Dent Care 2010; 17: 65–71.

Turner S, Ross M K, Ibbetson R J . Job satisfaction among dually qualified dental hygienist-therapists in UK primary care: a structural model. Br Dent J 2011; 210: E5

Office of Fair Trading. The private dentistry market in the UK. London: Office of Fair Trading, 2003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Turner, S., Ross, M. & Ibbetson, R. Dental hygienists and therapists: how much professional autonomy do they have? How much do they want? Results from a UK survey. Br Dent J 210, E16 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.387

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.387

This article is cited by

-

The perceptions and attitudes of qualified dental therapists towards a diagnostic role in the provision of paediatric dental care

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

Knowledge, opinions and practices of French general practitioners in the assessment of caries risk: results of a national survey

Clinical Oral Investigations (2017)

-

Direct access in the UK: what do dentists really think?

British Dental Journal (2015)

-

Oral cancer: Who best to detect oral cancer?

British Dental Journal (2015)

-

Dental skill mix: a cross-sectional analysis of delegation practices between dental and dental hygiene-therapy students involved in team training in the South of England

Human Resources for Health (2014)