Key Points

-

Highlights the importance of dental professionals being involved in smoking cessation activities and encourages them to do so.

-

Shows patients' willingness to follow dentists' advice in relation to giving up smoking.

-

Helps identify those patients who would benefit most from receiving information about the effects of smoking on their mouths.

Abstract

Background Smoking is correlated with a large number of oral conditions such as tooth staining and bad breath, periodontal diseases, impaired healing of wounds, precancer and oral cancer. These effects are often visible and in the early stages they are reversible after cessation of smoking. Dentists, as part of the health profession, are frequently in contact with the general population and there is evidence that they are as effective in providing smoking cessation counselling as any other healthcare group. Aims and methods Patients' knowledge of the effects of smoking and their attitudes towards the role of dentists in smoking cessation activities were analysed via a self-completing questionnaire and compared depending on their smoking status (smokers and non-smokers). Results The results show that patients hold very positive attitudes towards dentists' role in smoking cessation. The results also show that although patients have a good knowledge of the effects of smoking on general health, smokers are significantly less aware of the relationship between smoking and gum disease and on wound healing. Conclusions Dentists should inform their patients about the oral effects of smoking and strongly advise them not to smoke, especially in patients diagnosed with periodontal disease and requiring surgical procedures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Smoking is correlated with a large number of oral conditions such as tooth staining and bad breath, periodontal diseases, impaired healing of wounds and the life-threatening conditions precancer and oral cancer.1 These effects are often visible, and in the early stages they are reversible after cessation of smoking.2,3 In addition, dentists are one of the health professions more frequently in contact with the general population,2 and there is evidence that they are as effective in providing smoking cessation counselling as any other healthcare group.1

In this study patients' knowledge on the effects of smoking and their attitudes towards the role of dentists in smoking cessation activities were analysed and compared depending on their smoking status (smokers and non-smokers).

Study Design

This study was a cross sectional study via a self-completing questionnaire for patients. Comparison groups were smokers and non-smokers.

The objectives of the study were:

-

1

To assess the awareness of patients about the consequences of smoking on their general and oral health

-

2

To assess the attitudes of patients regarding the role of their dentists in smoking prevention, counselling and cessation

-

3

To analyse the willingness of smokers to follow dentists' advice.

Materials and Methods

The questionnaire

The questionnaire was a modification of those used previously by Humphris et al., Rikard-Bell et al., Bader et al., Lung et al. and Al-Shammari et al..4,5,6,7,8 The questions concerned socio-demographic characteristics, smoking status, knowledge about the effects of smoking on general and oral health, and patients' attitudes about the involvement of their dentists in smoking cessation activities.

Study population and recruitment

In June 2006, a batch of 20 questionnaires was sent to each of 27 dental practices from a total of 60 working within the Southern Health and Social Services Board in Northern Ireland (45% of the total). The practices were chosen to represent the area with regard to geographical area, practice size, rural/urban location and gender of dentist. Three months later, the letters were sent again to the practices that had not returned the questionnaires, and followed up by phone or a practice visit two and four weeks later to encourage participation.

The questionnaires were administered by the dentist and completed by the patient, and all patients received the same questionnaire. The patient inclusion criteria were:

-

Male or female over 16 years old

-

Smokers, non-smokers or ex-smokers

-

Able to read, understand and answer the questionnaire

-

Gave verbal consent to participate in the survey.

Data collection lasted six months. Questionnaires were forwarded by mail through a pre-paid envelope or collected by the research team personally from the dental practice.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses of the data were performed using the SPSS 14.0 for Windows statistical package.

Frequency counts were used to describe the answers. The associations between the different questions and the socio-demographic variables were analysed by cross-tabulation. The statistical significance of such relationships was determined mainly by Chi-square analysis (Pearson χ2 test and Fisher's Exact test) as variables were mainly categorical (nominal or ordinal). For the few continuous variables (age, years smoking), as they did not follow a normal distribution, non-parametric methods such us the Mann-Whitney U test were used.

For those questions concerning knowledge about the effects of smoking, a numerical transformation was performed to analyse the answers as a mean and thus rank them. For all the conditions known to be affected by smoking, the following values were given: yes = +1; don't know = 0; no = −1. For the only condition that is not affected by smoking (caries), the following values were given: no = +1; don't know = 0; yes = −1.

For those questions concerning patients' attitudes, a numerical transformation was also performed to obtain values on a scale from −2 (strongly disagree) to +2 (strongly agree), showing the mean opinion of the sample. The following values were given: strongly disagree = −2; disagree = −1; neither = 0; agree = +1; strongly agree = +2.

Results

Response rate

Seventeen dental practices (63%) took part in the study and returned 257 questionnaires (47.5%), from which two had to be excluded because they were incomplete.

Socio-demographics

Socio-demographic characteristics and smoking status of the sample can be observed in Table 1. More than half of the sample (57%) were non-smokers, 30% currently smoked and the remaining 12.5% were ex-smokers.

Knowledge about general and oral health

To the question 'How do you think smoking affects the oral health?' the responses most frequently given were teeth stain (86 responses), bad breath (66), gum disease (33) and cancer (28). The vast majority of respondents correctly answered that smoking affects lung cancer (98%), heart disease (92%), teeth staining (97%), halitosis (95%) and bad taste (92%) (Table 2).

Although most of the respondents correctly thought that tobacco affects gum disease (80%) and oral cancer (86%), a high number of patients said that they did not know if smoking affected these conditions (16% and 12% respectively). The association between smoking and impaired wound healing was acknowledged by 59% of the sample, but 33% of patients stated that they did not know if this relationship existed and 8% incorrectly stated that this association did not exist. Sixty percent of patients said that smoking was related to teeth decay, when this association has never been proved.2 Only 10.5% correctly answered that there is no such association (Table 2).

The influence of the current smoking status of subjects on their answers was analysed (Table 2). It can be observed that for all the conditions affected by smoking, a higher percentage of non-smokers answered 'Yes', ie they were more aware of the association than smokers.

Responses to the question 'Do you think smoking affects healing of wounds?' were strongly affected by the smoking status of respondents: significantly more smokers than non-smokers answered 'No' (14% vs 2.5%; p value 0.002).

Responses to the question 'Do you think smoking affects gum disease?' were also strongly influenced by the smoking status of respondents: significantly more smokers than non-smokers answered 'No' (8.5% vs 1%; p value 0.009).

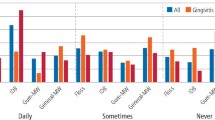

When the numerical transformation was performed (Fig. 1), it was observed that the patients sampled were correctly aware of the existing relationship between smoking and all the conditions with the exception for teeth decay. The association between smoking and oral medical conditions were the less well known by patients. Oral cancer, gum disease and impaired healing of wounds were ranked 6th, 7th and 8th, well after medical general conditions and after aesthetic and social oral conditions.

Attitude towards the dentist and smoking cessation counselling

A majority of patients from this survey showed a very positive attitude to the role of the dentist in smoking cessation and agreed with the statements 'I would expect my dentist to be interested in my smoking status' (81.5%), 'I would expect my dentist to explain the effects of smoking on the oral health' (86%), 'I would appreciate my dentist to provide smoking advice' (83%) and 'Dentists should be interested in the smoking status of their patients' (77%) (Table 3). The majority of patients from this survey disagreed with the statements 'I would change to another dentist if my dentist asked my smoking status this visit' (78.5%) and '...every visit' (73%), 'Dentists should provide oral care, nothing more' (55%), 'Dentists should not give smoking cessation advice' (60%) and 'Dentists do not know how to help patients to stop smoking' (53%) (Table 3).

The influence of current smoking status on patients' attitudes to the role of dentists in smoking cessation is shown in Table 3. It can be observed that both smokers and non-smokers held positive attitudes towards the involvement of dentists in smoking cessation activities. The mean opinion of the sample was studied after numerical transformation (Fig. 2). Overall, patients' top expectations were that dentists explained the effects of smoking on oral health, that they were interested in their patients' smoking statuses and that they provided smoking advice.

Smokers also showed positive attitudes towards counselling of dentists regarding smoking cessation (Table 4): 81% of smokers said that they would try to quit if their dentist showed them an effect of smoking on their mouth, with only a 4% saying that they would not. Sixty-nine percent stated that they would try to quit the habit if their dentist suggested so and 60% said they would go to a GP or a specialist for smoking cessation if their dentist suggested so.

Discussion

The percentage of smokers from this sample (30%) is a fairly good representation of the whole population (27% of adults in the UK are smokers1). It is also similar to that from other samples,5,7,8 summarised in Table 5.

The very positive opinions of the patients concerning the involvement of dentists in smoking cessation programmes are likely to be overstated, as responses from self-administered questionnaires tend to reflect what the respondents think that the person or organization conducting the survey expect. However, the results provide general and comparable information about what the population sampled think on this matter today, which can be used to track changes in attitudes over recent years as outlined in Table 5.

The effects of smoking were in general well acknowledged by people from this sample. However, its effects on oral medical conditions were on average less well known. Oral cancer, gum disease and impaired healing of wounds were ranked well below medical general conditions like lung cancer and heart disease. Furthermore, aesthetic and social effects like teeth staining, bad breath and bad taste were described more often as an effect of smoking than other more severe conditions like gum disease and oral cancer. Teeth staining, bad breath and bad taste can be evident to all and thus easily acknowledged, but there are still too many people who do not perceive oral cancer as a real danger, despite all the campaigns against mouth cancer performed by governments and health organisations.

The aesthetic effects of smoking should be highlighted and used as motivating factors by dentists when suggesting that their patients stop smoking. Nevertheless, dentists should be aware that the population are generally less concerned and knowledgeable about the real dangers of smoking to aspects of oral health and the profession should inform their patients about these. The rest of the dental team, especially dental hygienists, are in a privileged position as well and should be involved in smoking cessation activities.

Comparison between the results of this study and previous ones can be observed in Table 5. There was little change in patient knowledge between the study of Rikard-Bell in 20035 and the present study, with the exception of an improvement from 74% to 85.5% in relation to oral cancer and from 49% to 59% in associating poor wound healing with smoking. The present study shows some contrasts to that of Al-Shammari in 2006,8 with an increased awareness of the effect of smoking on oral cancer and wound healing in our study group. Although the populations differed with regard to geographical location and sample size, those changes are possibly showing a positive effect of oral health promotion.

It was observed in our study that for all the conditions affected by smoking, non-smokers were more aware of these effects than ex-smokers and smokers (Table 2). Differences between smokers' and non-smokers' knowledge reached statistical significance for impaired healing of wounds (p = 0.002) and gum disease (p = 0.009). This is an important finding, as it has clinical consequences. It is well known that smoking delays healing of wounds and increases gum disease.1,2,9 Dentists should be informed of this lack of awareness and strongly advise and inform smokers about these dangers, especially after surgical procedures such as extractions and periodontal therapy. In doing so, dentists can provide additional motivation and influence smokers' actions and help to increase the number of smokers who quit, thus diminishing the progression of their illness and improving the outcome of the therapy.

The vast majority of patients from this sample, including smokers, had very positive attitudes towards the role of dentists in smoking cessation activities (Table 3). They would welcome support from their dentist, especially when they were aware of an effect of smoking on their mouths. These findings show that dentists have a great potential to motivate people to stop smoking. Other effects of smoking are not as visible and tangible as the oral effects.3,10 Dentists should not hesitate to give smoking advice to their patients and grasp this opportunity to improve the oral and general health of the community.

Conclusions

Patients in this sample have a good general knowledge about the effects of smoking. Aesthetic and social effects are the ones that people perceive more and could be used as motivating factors for smoking cessation. The effects of smoking on oral health, such as gum disease, oral cancer or impaired healing of wounds, are less well known and require further education.

Smokers are significantly less aware than non-smokers of the relationships between smoking and gum disease and smoking and impaired wound healing. Dentists should inform their patients and strongly advise them not to smoke when they are diagnosed with periodontal disease or after surgical procedures such as extractions or periodontal therapy.

All patients, including smokers, have very positive attitudes and high expectations towards their dentists' involvement in smoking cessation activities. Smokers are willing to follow their dentists' suggestions and advice. Dentists should not hesitate to counsel their patients to stop smoking and to show them the visible effects of smoking as soon as they appear.

References

Beaglehole R, Watt R . Helping smokers stop: a guide for the dental team. London: Health Development Agency, 2004.

Johnson N W, Bain C A, the EU-Working Group on Tobacco and Oral Health. Tobacco and oral disease. Br Dent J 2000; 189: 200–206.

Watt R G, Daly B, Kay E J . Prevention. Part 1: smoking cessation advice within the general dental practice. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 665–668.

Humphris G M, Field E A . An oral cancer information leaflet for smokers in primary care: results from two randomised controlled trials Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2004; 32: 143–149.

Rikard-Bell G, Donnelly N, Ward J . Preventive dentistry: what do Australian patients endorse and recall of smoking cessation advice by their dentists? Br Dent J 2003; 194: 159–164.

Bader J D, Rozier R G, McFall W T et al. Association of dental health knowledge with periodontal conditions among regular patients. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1990; 18: 32–36.

Lung Z H S, Kelleher M G D, Porter R W J et al. Poor patient awareness of the relationship between smoking and periodontal disease. Br Dent J 2005; 199: 731–737.

Al-Shammari K F, Moussa M A, Al-Ansari J M et al. Dental patient awareness of smoking effects on oral health: comparison of smokers and non-smokers. J Dent 2006; 34: 173–178.

Ramseier C A, Tönnesen P, Bornstein M, Palmer R (2006). Tobacco use cessation and oral health management. Oral symposium at the International Association of Dental Research – Pan European Federation meeting, Dublin 13–16 September 2006.

Chestnutt I G, Binnie V I . Smoking cessation counselling – a role for the dental profession? Br Dent J 1995; 179: 411–415

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the support of the Southern Health and Social Services Board. We would like to thank all the dentists and patients who took part on this survey and without whom this study would not have been possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Terrades, M., Coulter, W., Clarke, H. et al. Patients' knowledge and views about the effects of smoking on their mouths and the involvement of their dentists in smoking cessation activities. Br Dent J 207, E22 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.1135

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.1135

This article is cited by

-

Patient awareness of oral cancer health advice in a dental access centre: a mixed methods study

British Dental Journal (2011)

-

Summary of: General dental practitioner views on providing alcohol related health advice; an exploratory study

British Dental Journal (2010)