Key Points

-

Investigates dental therapists' perspectives on teamwork within a range of clinical settings in the UK.

-

Describes dental therapists' feelings of inclusion within the dental team, whether dental colleagues referred patients to them and whether their skills were fully utilised in their work setting.

Abstract

Objectives To determine whether practising dental therapists, including dually qualified hygienist/therapists, considered themselves to be part of the clinical team and whether clinical work referred to them met with their expectations. Methods A postal survey enquired about work experiences of UK dental therapists, as previously described earlier in the series. Results While they certainly considered themselves to be part of the clinical team, the majority of respondents did not feel 'fully utilised'. Seventy percent of respondents felt that the dentist had more patients that could be referred and 55% thought that they could do more extensive work. There was concern that dentists lacked awareness of therapists' clinical potential, although some respondents highlighted very positive experiences in practice. Conclusions Dental therapists feel that they are part of the clinical team but consider that their skills are not fully utilised in many cases. There is scope for raising awareness among dentists regarding the therapists' clinical potential as well as sharing ideas for good working practice both within individual clinical settings and between different practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is widespread use of professionals complementary to medicine.1 Much routine care is now performed by individuals who are not medically qualified but who have received appropriate training and are permitted to perform specific procedures.2

In contrast, dentistry has been slower to develop. Yet the current difficulties in recruiting dentists in the UK have been seen as an opportunity for dental care professionals (DCPs), including therapists and dually qualified hygienist-therapists, to emerge as a group that could undertake much of routine dentistry,3 especially in areas of high need.4,5

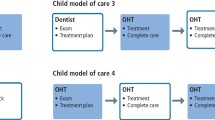

The concept of the dentist leading a flexible workforce offering an interchangeable mix of skills has been around for many years.6,7 As team leader, the dentist is responsible for providing a written prescription, together with the diagnosis, treatment planning and quality control of treatment provided.8 The General Dental Council (GDC) document Scope of practice9 provides clarity regarding the items of dental care that therapists can provide under the prescription of a dentist. While the care is under the dentist's supervision, it does not require the dentist to be present. The increasing numbers of therapists, their expanding remit and the changes in legislation to allow working in general dental practice is making this vision an increasing possibility.

It has been estimated that a very significant percentage of NHS general dental service (GDS) workloads could be completed by therapists, leaving dentists free to perform the more complex procedures and to see more patients.3,4 In the past, dentists in general dental practice have expressed concerns about the quality of therapists' clinical work due to inadequate training,10 but this issue has recently become less prominent.4,11,12,13 Dentists' lack of knowledge about what therapists do, coupled with their lack of approval, were also thought to be a barrier,4 together with patients' acceptance and satisfaction.4,10

Dental therapists have been working within the UK NHS salaried and hospital services for many years, mainly treating children and adults with special needs. Collaborative working with referring dentists has been long established, although even here things are changing, as dental therapists working in salaried settings have had the potential to offer a wider range of clinical treatments, subject to successfully completing the required competency training, since 2002. The GDC Scope of practice9 has also clarified the role of dental therapists (and other registered members of the dental team), detailing the items of treatment they can carry out and additional skills they may develop during their careers.

In general dental practice, working with dental therapists is a newer experience. The personal dental services (PDS) pilots in England provided a range of models to test alternative ways of delivering dental services and different ways of working.14,15,16 PDS practice profiles varied and compared with dentists working in the same practices, could involve therapists (a) treating a higher proportion of children, (b) treating a higher proportion of adults exempt from NHS payments, (c) performing more scales and polishes, (d) performing more dental health education, (e) performing more fissure sealants and (f) undertaking more preventive-based visits.14 Previous surveys of dentists have indicated that children and people with special needs were considered particularly suitable for referral,4,17 being time-consuming and demanding.18 Survey responses have also implied that some dentists perceive NHS rather than private practice as the appropriate working environment for therapists.4

It is against a background of evolving teamwork and contrasting views that the present aspect of the survey was undertaken. In particular, it was considered important to explore the perspective of all UK dental therapists who were currently working within various training backgrounds,19 across a range of clinical settings. The aim of this study was to enquire into whether practising dental therapists considered themselves to be part of the clinical team and whether the referral arrangements they experienced in clinical practice paralleled their expectations. A secondary aim was to identify characteristics associated with these responses and to collate the qualitative results obtained from semi-structured and open questions.

Materials and Methods

This analysis was restricted to those 470 respondents who stated in the previously described questionnaire that they were working as a therapist, either part-time or full-time.20 The quantitative analysis was based on three key questions in the semi-structured questionnaire relating to aspects of 'teamwork', regarding their level of agreement about whether they felt part of a clinical team, whether they thought that the dentist had more patients that could have been referred to them, and whether they could do more extensive work if the patients were referred to them.

Previous papers in the series have reported on the respondents' years of qualification, NHS commitments and clinical work,20 and remuneration arrangements.21 This information was cross-tabulated with the stated views about 'teamwork'. Data analysis included Chi square tests and binary logistic regression analysis (to allow for confounding factors) at the <5% level of probability.

The questionnaire included semi-structured and open questions which allowed respondents to supply additional information, either in relation to the questions asked in the schedule, or to address other related topics. Thematic analysis was undertaken in order to draw out key points to help clarify and illustrate issues arising from the quantitative data.

Results

The response rate from the questionnaire was 80.6%. Overall, 94% of respondents were located in England and Wales. Of the 470 who stated that at least some of their working time was spent on therapy duties, 192 had qualified separately as a therapist and as a hygienist, while 58 had completed more recent programmes offering dual qualifications. Of the 210 trained at New Cross19 (representing a larger proportion of older therapists), 201 had undertaken 'extended duties' training.

The responses to the three key questions and relevant inter-relationships were examined.

'I feel part of the clinical team'

The respondents were asked whether or not they agreed with the above statement. Ninety-six percent of respondents stated that they agreed or strongly agreed (Table 1).

Positive comments (n = 11) included:

'I am privileged to work in a practice that uses my skills to their full potential. I am definitely part of the team and they are keen for me to extend my skills further.'

'I am working as a therapist in all three practices and although it took some persuasion it now works very well in general practice and I carry out almost all duties. I am lucky to be working with forward thinking dentists who accept therapists and we now work very well together. Patients are always happy to be seen by a therapist if it is explained properly to them.'

However, there were some negative views (n = 11):

'I feel treated as an outsider and not part of a clinical team. I don't belong anywhere.'

'The dentist has more patients that could be referred to me'

Over two thirds (70%) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with this statement (Table 1). Those who thought that more could be referred:

-

Had been qualified in dental therapy most recently (2004-2006 – 78%)

-

Spent their time mainly in private practice (10-48% NHS: 86%)

-

Worked in a general practice setting (78%).

Those respondents whose work was limited to general dental practice are also included in Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 shows a clear gradient, with recently qualified therapists more likely to feel that 'more patients could be referred'. However, when those working exclusively in general dental practice were assessed, it is clear that the year of qualification makes less difference. Logistic regression was performed with agreement or disagreement with the statement 'the dentist has more patients that could be referred to me' as the dichotomous dependent variable. The significant dichotomous predictor variables in descending order of importance were 'being self-employed' and 'working in private general dental practice'.

Some respondents highlighted the relevant background issues:

'It is difficult to find work as a therapist as I don't think many dentists are confident or willing to refer work.'

'As a full-time self-employed dental therapist, I am trying to encourage the practices where I work to use my therapy skills, but at present to no avail.'

Others specifically mentioned that they were referred hygiene work, when they could perform restorative work:

'Dentists still do not use me to their fullest advantage by passing me the majority of their fillings patients. I find it frustrating as the majority of my clinical time is spent working on hygiene.'

'Dentists seem to have no problem with referring for hygiene work, or referring children, but ... still great reluctance to refer restorative work on adult patients.'

'I could do more extensive work if the patients were referred to me'

Over half (55%) of the sample agreed or strongly agreed with this statement (Table 1). Those who thought that they could do more extensive work:

-

Had been qualified in dental therapy between 1997-2003 (61%)

-

Spent their time mainly in private practice (10-48% NHS: 68%)

-

Worked in a general practice setting (60%).

Figures 3 and 4 illustrate these points.

Logistic regression addressed the statement that 'I could do more extensive work if the patients were referred to me' as the dichotomous dependent variable. The significant predictor variables in descending order of importance were 'being self-employed' and 'on performance-related pay'.

Of those responses providing more in-depth qualitative information, themes and sub-themes relevant to this analysis have been summarised in Table 2. The most frequent comments related to the therapists' belief that dentists were not aware of the scope of their work, or how they could be effectively used (n = 35). However, a smaller proportion felt that things were changing (n = 29). Some were not happy with aspects of their work, including the range of referrals received (n = 22). Concerns about their status as part of the team appeared to be mainly negative (n = 20).

Points of clarification provided by respondents included limited perceptions of therapists' competencies by dentists, the public and other members of the dental team (n = 77):

'Many dentists still think dental therapists can either only treat children, or adults as well but only for scale and polish and Class 1 cavities.'

'...the idea of 'simple' fillings for therapists means that dentists believe this refers to single surface cavities only. The word 'simple' still seems to be a barrier to passing patients on to the therapist for some dentists.'

'Please can the term 'simple fillings' be changed – I kept encountering dentists and nurses who think we can just pick up a drill like a proper dentist and do a quick buzz and do a tiny occlusal cavity/restoration. The restorations I was doing before were usually multi-surface, enormous ones.'

Some therapists felt that their situation might be changing in this respect:

'I have pointed out in the three practices in which I work that I could treat every adult that needs a hygiene appointment plus one or two fillings in an hour's appointment ... I still find these patients are being booked with me for the hygiene work and with the dentist for the fillings. I find this frustrating at times ... the underlying inference seems to be that dentists still don't believe we are capable of doing filling work on adults, using all materials... However in one of the practices I work, I am starting to see a few more adults, but it is very slow.'

Other semi-structured and open responses have been themed below.

Awareness of therapist duties within the dental team

This provided a series of recurring themes. Some respondents thought that dentists did not know what therapists can do, how to make appropriate use of their range of skills or were not confident in their abilities. As a result, it was hard to find work.

'I am amazed by the number of dentists I have met who still have no idea of the work that therapists can do.'

'Still many dentists don't know what a therapist can do and how to use them to maximise patient care and profitability.'

'It's difficult to persuade dentists that dental therapists could really help them to run a smoothly operating team.'

There were quite a number of respondents who felt that their clinical potential was limited by being only referred children, often with behaviour problems, or alternatively that they were only used for hygiene duties.

The lack of nursing assistance was also mentioned.

'Dentists think we mainly specialise in children and especially those that are non-compliant.'

'The cases which dentists find difficult [behaviourally] are referred to me. This, in turn, means that I only see difficult children.'

This topic provided a mix of responses. Some felt that their clinical work was limited to NHS or exempt adults only, while others had the opportunity to work across a range of settings.

'Therapists are very good at what they do and are capable as dentists in doing both NHS and private work. Patients love us!'

'While working at private/mixed practice I do a full range of therapy duties – only a few scale and polishes. I see a whole range of ages – tiny tots, teenagers, elderly. I do many preventive resin restorations ... I do many stainless steel crowns ... with great success ... fissure sealants, impressions. My main work is restorations which I enjoy and can use whatever materials I want.'

'I feel initially there was a reluctance to pass on private treatment for adults as the dentist thought dental therapy training was not to the same standard as for general dental practitioners. Once the dentist saw the standard of my work, he began to start referring more private patients.'

Working conditions

Some respondents explained specific situations that applied in their practices, a few of which are outlined below. Some provide additional insights into the ways that some therapists may be treated in practice.

'The dentists only give me restorations when my hygiene patients have not turned up so I do his work for him and he doesn't have to pay for an extra dental nurse.'

'If the dentist's equipment fails or nurses are not available I have been made to swap room with that dentist or go without a nurse as they are seen as being 'more important' members of the dental team.'

'We have a new associate dentist at my main private practice and so my therapist duties have been reduced in recent weeks. I'm carrying out more hygiene duties.'

'I will soon be doing more dental therapy time as one dentist is reducing his hours and so I will be working with children.'

Therapist status: negative comments

Therapists provided a mixed selection of responses regarding the way they felt that they were perceived in the practice setting.

'The therapist's position in the hierarchy of the team is not fully understood by some members of team,ie not a hygienist yet not quite a dentist.'

'Some of our dentists still refer to me as “the hygienist” ... despite the fact that I am not dually qualified and that I have been working here for 36 years!'

'The dentists I worked with in general dental practice had no experience of therapists and treated me as an extra dentist but with poor payment.'

Therapist status: positive comments

The comments provided also offered examples of successful practice. Some therapists felt that they were treated as equals, valued, supported and working to their full potential. There were appropriate referrals arrangements and patients were accepting of the arrangements.

'I am referred all kinds of treatment but under no pressure to do anything I am not trained to do. I am treated as an equal and paid accordingly.'

'I work in a practice under the new dental contract with four dentists. I see a big mix of patients doing a large variety of work, both adults and children. The practice appreciates me and I have made a real difference. I allow the dentists greater time for any complicated treatment plans. I also see emergency lost fillings. The dentist pops in first and provides a prescription for me to work from. This helps to keep patients happy and ensures they are seen much quicker. We have had a good response from patients – they have been asking to come back and see me.'

'The ones I work with love referring me all their routine treatment for people of all ages, their 'paedo' patients, their compromised patients, their phobic patients, etc etc – it leaves them free to do more specialised (and lucrative) work.'

Some additional responses provide a flavour of the degree of acceptance and support offered by some dentists as well as further evidence of patients' acceptance:

'Patients when initially referred are a little confused about my role in their treatment, but four years on, I have regular patients who “request” treatment from myself now, and are very appreciative of the care they receive from me.'

'I am very lucky to work in two forward thinking and supportive practices ... I am being encouraged to expand ... I am gaining confidence ... I really enjoy it.'

'My practice is at present mentoring me to develop my therapy skills so I will be doing more.'

Some therapists explained how they were trying to change the approach of the referring dentists within their current practices:

'I have now been working in one of my practices a year. I called a meeting to discuss the reason they initially employed me, explaining my love for the job yet not feeling completely fulfilled and wanting to do therapy work. As a result have now been referred some therapy patients. It takes time and determination yet one must persevere.'

Therapy and the future of the role

In view of the responses about the dentists' lack of awareness, some therapists addressed the possibilities for improving the situation. There was also the sense of frustration that an existing lack of awareness among dentists was stifling their job prospects.

'More needs to be done to let dentists know about how we work, the skills we have and how we are an asset to a practice.'

'I think the lack of therapy jobs and also possibly the lack of dentists' understanding of what therapists are all about and what we can do is making it difficult for us therapists to achieve our full potential.'

'It is time for a national campaign which fully educates dentists in what a therapist can do and how to use/employ them.'

'The government and university gave the impression that we were desperately needed to fill a niche in the dental environment ... as yet I am still waiting. General dental practitioners need educating about the advantages of a therapist. The NHS arrangements have constraints ... professionally and morally ... are my skills really going to be utilised?'

Discussion

The high response rate implies that these results are generalisable. However, respondents varied in the extent to which they provided additional details (in number and volume of information) in relation to the semi-structured and open questions which were posed. Ideally, the information gained here could inform a qualitative study design where issues around teamwork could be explored further in depth. The views of other members of the dental team could also be sought to provide a wider perspective and put their observations in context.

The overwhelming majority of respondents felt themselves to be 'part of a clinical team', although responses to subsequent questions suggest that this question lacked value judgements. A 1999 survey of dental therapists reported that two thirds of therapists felt like 'a valued member of staff' all or most of the time,22 implying that there could be room for improvement. That study was confined to therapists working in salaried services, before the introduction of 'extended duties' and expansion into general dental practice, factors which may have modified the response. However, this study found substantial signs of disquiet since over two thirds of respondents agreed that more patients could be referred to them. Similarly, over half the therapists agreed that they could do more extensive work, especially those who were self-employed and/or were on performance-related pay.

The present study indicates that therapists may resent dentists failing to recognise their range of skills and being restricted to undertaking a limited range of clinical duties, such as hygiene. A recent survey of dental practice principals found that 39% would expect more than 50% of therapists' working time to be spent on hygiene,23 while it was also accepted that some 'therapy-specific treatments' would be performed. A more recent study confirms that their restorative skills are being under-utilised.23 Previous surveys of dentists have found that children and people with special needs have been deemed as most suitable for treatment by therapists,4,17 and some general dental practitioners (GDPs) incorrectly believed that therapists are only allowed to undertake operative procedures on children.4,18 Limiting clinical work to children and especially 'difficult' children, with no opportunity to see adults, was also identified here as a potential source of resentment. Previous studies have indicated that 54% of GDPs in 2000 thought that adults were a suitable client group to be treated by therapists4 compared with 21% in 1990 in a study by Hay and Batchelor.17

This study offered a dichotomy of views over the NHS/private mix. A larger proportion of the therapists working in mainly private practices felt that more patients and more extensive work could be referred to them. Some qualitative responses indicated a potential reluctance to refer fee-paying adults, an issue mentioned elsewhere.4,23 Yet hygienists are mainly based in private practice. One study in the South West of England reported that only one fifth of sessions were NHS-funded and 75% of hygienists undertook no NHS sessions at all.24

The present study illustrated a range of positive ways of working that involved both private practice and fee-paying NHS adults. The underlying themes included patient acceptance, which has been linked to dentists' acceptance.25 Therapists' views about their perceived status were clearly part of this, illustrated by a range of positive reactions. In contrast, some dentists and the public are uncertain about what therapists do and who they are. There is a substantial need for practice-based initiatives to clarify the situation.

Dentists' lack of awareness has been reported previously4 and can have profound effects on acceptance of therapists by the dental profession and the public.23,26 This can range from not understanding the range of clinical competencies and therefore what to refer, through to not valuing/understanding the therapist's clinical expertise enough to help share the workload. For therapists to be effective and efficient members of the dental team, the dentist must delegate a range of appropriate tasks to them.27,28,29 One survey reported that the majority (59%) of GDPs thought (incorrectly) that therapists must work only under the direct supervision of a dentist,4 rather than to a written treatment plan. In the wider context, this misunderstanding will impact on the lack of job opportunities for recently qualified therapists.

This study has also highlighted a range of good working practices, where therapists feel valued, consulted and supported as full team members. In other situations, it is clear that therapists feel that the dentist is not listening! Previous experience with PDS pilots recorded that DCPs felt that they were not adequately consulted as part of managerial involvement.15 It has been suggested that dentists can feel frustrated with time spent on management.30 It can be stressful coping with conflicting demands of different roles. Dentists may lack confidence to work with therapists and to take charge to support team working.23

A culture shift is needed to share power.16 Mutual trust, understanding and clinical confidence are important components of good working relationships.16 Some responses identified in this survey reflect levels of stress that current working practices engender. It has been argued that the dentists' quality of life may benefit from a skill-mix, team-based approach,31 but the quality of life of all members of the team should be considered.

The need to improve dentists' knowledge and awareness about working with therapists has been clearly demonstrated in this and previous studies.4,23,26 Seward (1999) argued for imaginative employment of DCPs.32 But dentist education is required to fully explore the skill-mix being appropriately used.4,23,26,33

This is likely to require a two-pronged approach; firstly, to understand what therapists are trained to do and the level of supervision required. While referrals to therapists were often reported as too limited, there were a few others beyond their levels of competency. Dentists should only ask therapists to undertake a treatment if they are confident that they have been trained and are competent in that procedure.34 Good communication could help to resolve many of these issues. The required knowledge should be easy for future generations to achieve with undergraduate opportunities for joint teaching with parallel and integrated course and clinical work. For postgraduates, in addition to continuing professional development (CPD), it has been suggested that substantial central support will be required and that the GDC should take the initiative for disseminating appropriate information.23

Secondly, larger group practices are best placed to employ a therapist.4 Any supervising dentist leading the dental team needs appropriate management skills in order to work efficiently with a therapist.25 It is the duty of a dentist to create incentives and job satisfaction to encourage therapists to work to the upper limits of their abilities.35 For effective team working the supervising dentist must provide good leadership, ensuring that aims are clear, agreed and shared so that the team can work together to achieve them.34 The supervising dentist has a range of responsibilities to the team including encouraging them to work together effectively, while putting systems in place to review and monitor individual and team performance.34

Vocational training and CPD have been seen as possible conduits to increase the number of dentists able to head dental teams,10 but sharing good practice such as has been identified here can go some way to showing what is possible.

In conclusion, this study has found that while UK-based practising dental therapists considered themselves to be part of the clinical team, up to two thirds felt that the referral arrangements they experienced in clinical practice did not meet their expectations. Those who were most likely to be dissatisfied were more recently qualified and working in predominantly private practices. There is scope for raising awareness among dentists regarding therapists' clinical potential as well as sharing ideas for good working practice both within individual clinical settings and between different practices.

References

Department of Health. Modernising dentistry: implementing the NHS plan. London: The Stationery Office, 2000.

Ross M K. The increasing demand and necessity for a team approach. Br Dent J 2004; 196: 181.

Evans C, Chestnut I G, Chadwick B L . The potential for delegation of clinical care in general practice. Br Dent J 2007; 203: 695–699.

Gallagher J L, Wright D A . General dental practitioners' knowledge of and attitude towards the employment of dental therapists in general practice. Br Dent J 2002; 194: 37–41.

Harris R V, Haycox A . The role of team dentistry in improving access to dental care in the UK. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 353–356.

The Nuffield Institute. The education and training of personnel auxiliary to dentistry. London: The Nuffield Institute, 1993.

The Nuffield Institute. An inquiry into dental education. A report to the Nuffield Foundation. London: The Nuffield Institute: 1980.

General Dental Council. Developing the dental team. Curricula frameworks for registerable qualifications for professionals complementary to dentistry (PCDs). London: GDC, 2004.

General Dental Council. Scope of practice. London: GDC, 2009.

Woolgrove J, Boyles J . Operating dental auxiliaries in the United Kingdom - a review. Community Dent Health 1984; 1: 93–99.

General Dental Council. Final report on the experimental scheme for the training and employment of dental auxiliaries. London: GDC, 1966.

Allread H. A series of mongraphs on the assessment of the quality of dental care, experimental dental care programme. London: London Hospital Medical College, 1977.

Sisty N L, Henderson W G, Paule C L . Review of the training and evaluation studies in expanded functions for dental auxiliaries. J Am Dent Assoc 1979; 98: 233–248.

Harris R, Burnside G . The role of dental therapists working in four personal dental service pilots: type of patients seen, work undertaken and cost-effectiveness within the context of the dental practice. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 491–496.

Goodwin N, Morris A J M, Hill K B et al. National evaluation of personal dental services (PDS) pilots: main findings and policy implications. Br Dent J 2003; 195: 640–643.

Ward P. The changing skill mix - experiences on the introduction of the dental therapist into general dental practice. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 193–197.

Hay I S, Batchelor P A . The future role of dental therapists in the UK: a survey of district dental officers and general dental practitioners in England and Wales. Br Dent J 1993; 175: 61–65.

Ireland R S. Dental therapists: their future role in the dental team. Dent Update 1997; 24: 269.

Rowbotham J S, Godson J H, Williams S A, Csikar J I, Bradley S . Dental therapy in the United Kingdom: part 1. Developments in therapists' training and role. Br Dent J 2009; 207: 355–359.

Godson J H, Williams S A, Csikar J I, Bradley S, Rowbotham J S . Dental therapy in the United Kingdom: part 2. A survey of reported working practices. Br Dent J 2009; 207: 417–423.

Williams S A, Bradley S, Godson J H, Csikar J I, Rowbotham J S . Dental therapy in the United Kingdom: part 3. Financial aspects of current working practices. Br Dent J 2009; 207: 477–483.

Naidu R, Newton J T, Ayers K . A comparison of career satisfaction among dental healthcare professionals across three health care systems: comparison of data from the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Trinidad and Tobago. BMC Health Serv Res 2006; 6: 32.

Jones G, Devalia R, Hunter L . Attitudes of general dental practitioners in Wales towards employing dental hygienist-therapists. Br Dent J 2007; 203: E19.

Sprod A, Boyles J . The workforce of professionals complementary to dentistry in the general dental services: a survey of general dental practices in the South West. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 389–397.

Douglass C W, Lipscomb J . Expanded function dental auxiliaries: potential for the supply of dental services in a national dental program. J Dent Educ 1979; 43: 556–567.

Ross M K, Ibbetson R J, Turner S . The acceptability of dually qualified dental hygienist-therapists to general dental practitioners in South-East Scotland. Br Dent J 2007; 202: E8.

Douglass C W, Gillings D B, Moor S, Lindhal R L . Expanded duty dental assistants in solo private practice. J Am Coll Dent 1976; 144: 969–984.

Burman N. Attitudes to the training and utilisation of dental auxiliaries in Western Australia. Aust Dent J 1987; 32: 132–135.

Stephens C D, Keith O, Witt P et al. Orthodontic auxiliaries - a pilot project. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 181–187.

Newton J T, Gibbons D E . Stress in dental practice: a qualitative comparison of dentists working within the NHS and those working within an independent capitation scheme. Br Dent J 1996; 180: 329–334.

Gibbons D, Newton T . Personnel management. In Stress solutions for the overstretched. Chapter 8. pp 51–56. London: BDJ Books, 1998.

Seward M. PCD - what's in a name? Br Dent J 1999; 187: 1.

Steele J . Review of NHS dental services in England. London: Department of Health, 2009.

General Dental Council. Principles of dental team working. London: GDC, 2006.

Jones D E, Gibbons D E, Doughty J F . The worth of a therapist. Br Dent J 1981; 151: 127–128.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by NHS R&D in Primary Dental Care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Csikar, J., Bradley, S., Williams, S. et al. Dental therapy in the United Kingdom: part 4. Teamwork – is it working for dental therapists?. Br Dent J 207, 529–536 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.1104

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.1104

This article is cited by

-

What are the possible barriers and benefits to the use of dental therapists within the UK Military Dental Service?

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

The perceptions and attitudes of qualified dental therapists towards a diagnostic role in the provision of paediatric dental care

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

What are the possible barriers and benefits to the use of dental therapists within the UK Military Dental Service?

BDJ Team (2022)

-

A global review of the education and career pathways of dental therapists, dental hygienists and oral health therapists

BDJ Team (2021)

-

A global review of the education and career pathways of dental therapists, dental hygienists and oral health therapists

British Dental Journal (2021)