Abstract

ABO3 perovskites are oxide materials that are used for a variety of applications such as solid oxide fuel cells, piezo-, ferro-electricity and water splitting. Due to their remarkable stability with respect to cation substitution, new compounds for such applications potentially await discovery. In this work, we present an exhaustive dataset of formation energies of 5,329 cubic and distorted perovskites that were calculated using first-principles density functional theory. In addition to formation energies, several additional properties such as oxidation states, band gap, oxygen vacancy formation energy, and thermodynamic stability with respect to all phases in the Open Quantum Materials Database are also made publicly available. This large dataset for this ubiquitous crystal structure type contains 395 perovskites that are predicted to be thermodynamically stable, of which many have not yet been experimentally reported, and therefore represent theoretical predictions. The dataset thus opens avenues for future use, including materials discovery in many research-active areas.

Design Type(s) | database creation objective |

Measurement Type(s) | physicochemical characterization |

Technology Type(s) | computational modeling technique |

Factor Type(s) | compound by chemical composition |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data (ISA-Tab format)

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Due to their large tolerance to oxygen vacancy, ABO3 perovskites are widely used for a variety of applications such as solid oxide fuel cells, piezo-, ferro-electricity and thermochemical water splitting1–3. Furthermore, their remarkable structural stability with respect to their constituent elements suggests that potential new compounds remain to be discovered. As the number of possible ABO3 compounds is large, we use high-throughput density functional theory (HT-DFT) to compute the thermodynamical stability of 5,329 compositions in an exhaustive manner. In addition to the compounds stability, we also calculate the oxygen vacancy formation energies as it is a relevant quantity for many applications involving reduction of these compounds1–3. Due to their versatility, perovskites have been studied in several high-throughput works4–7. However, to our knowledge, those datasets are not publicly and/or easily available.

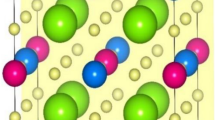

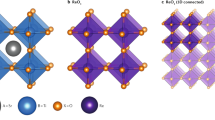

All the 5,329 compounds are created by substituting 73 metals and semi-metals of the periodic table of the elements (see Fig. 1) on the A and B sites (732=5,329) of the ABO3 perovskite crystal structure. The ideal ABO3 cubic perovskite crystal structure is composed of a B cation that is octahedrally 6-fold coordinated with oxygen atoms and an A cation that is 12-fold coordinated by oxygen atoms. Aside from the ideal cubic structure, many perovskites undergo a local distortion from this cubic structure, and these distorted perovskites can have a variety of symmetries, including the rhombohedral, tetragonal and orthorhombic distortions3 (see Fig. 2). In this work, all 5,329 compositions are calculated in the ideal cubic structure and a subset of those (see structural distortions paragraph in the Methods section) are calculated in the 3 aforementioned distortions.

(top left) We start with all the cubic structures and compute all their total energies using density functional theory (DFT). If the stability of the cubic perovskite (defined in Equation 2) is less than 0.5 eV per atom (i.e., the cubic phase is within 0.5 eV per atom of the ground state convex hull), we also compute 3 additional distortions (orthorhombic, tetragonal, rhombohedral). The geometric properties (lattice parameters, angles, and volume per atom) and electronic properties (band gap and magnetic moment) are readily available from the calculations. Formation energies are calculated using elemental chemical potentials and thermodynamic stability is calculated with respect to all the other A-B-O phases present in the OQMD. (top right) Defected perovskites, a 2×1×1 supercell with a missing oxygen atom, are calculated using DFT and their total energies, in conjunction with those of pristine cubic cells, are used to compute the oxygen vacancy formation energies.

The T=0 K, P=0 bar ground state stability of all ABO3 compounds was assessed with respect to all possible linear combinations of phases present in the A-B-O ternary phase diagram using a convex hull construction. All the phases that are used for the stability calculation are from the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD)8 and (as of July 2017) include ~40,000 phases from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD)9,10 and ~430,000 hypothetical compounds based on decoration of common structural prototypes. The oxygen vacancy formation energy was calculated by using an A2B2O5 structure, which corresponds to 2 perovskite unit cells with an oxygen atom removed. Additionally, other properties readily available from DFT calculations are reported, including the relaxed structure, band gap, and total magnetic moment. Figure 2 shows the workflow used to obtain all the quantities.

The present dataset was used in a study aiming at identifying suitable perovskites for thermochemical water-splitting applications using both the stability and oxygen vacancy formation energy as screening parameters11. This data is valuable more generally in guiding experimental synthesis of predicted new compounds, further screening for a large variety of applications (other than water splitting) or to train machine learning (ML) models. While machine learning on materials dataset is an area of active research12–14, the datasets used by various research groups are often vastly different from one another with no way to compare various ML models. Having a large, consistent materials dataset that can be used by a variety of research groups to train machine learning models will allow a more transparent comparison of various methods being used in the field.

Methods

Density functional theory calculations

All compounds were calculated by density functional theory using the Vienna Ab initio simulation package (VASP)15,16. The projector-augmented wave method (PAW)17 and GGA-PBE18, as an approximation to the exchange-correlation functional, were used throughout. 3d transition metals and most actinides were calculated using the DFT+U19,20 formalism (see Table 1 for U-values, U is applied on d-electrons for transition metals and f-electrons for actinides) and were spin-polarized with a ferromagnetic alignment of spin. Calculations were performed within the framework of the Open Quantum Materials Database8 which contains 470,000 different phases from experimental databases such as the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD)9,10 and hypothetical compounds based on common structural prototypes.

Calculation of formation energy

The formation energy of a compound, , is calculated according to Equation 1:

where E(ABO3) is the total energy of the perovskites and μA, μB and μO are the chemical potentials of A, B and oxygen, respectively. For most elements, chemical potentials are equal to the DFT total energies of their ground states. For some elements where the T=0 K DFT ground state is not an adequate reference state, we apply corrections to the chemical potentials: diatomic gases (O), room temperature liquid (Hg), several elements with structural phase transformations between 0 and 298 K (Na, Ti, Sn) and elements with DFT+U correction (see Table 1). For these elements, chemical potentials are fitted to experimental formation energies. Details of the experimental formation energies used and the resulting corrections are given in ref. 8.

Calculation of phase stability

Thermodynamic stability was assessed using an energy convex hull construction21,22. By definition, the convex hull consists of phases that have an energy lower than any other phase or linear combination of phases at the respective compositions. The stability, or convex hull distance is defined as

swhere is the formation energy of the perovskite, defined in Equation 1 and Hf is the convex hull energy at the ABO3 composition. For a given phase, P, the convex hull distance is positive if P is unstable and represents the energy difference between P and the convex hull at that composition. The convex hull distance is negative if P is stable and represents the energy difference between P and the (hypothetical) convex hull calculated without compound P. However, in this work, we wish to slightly loosen this restriction to account for nearly-stable compounds and possible uncertainties/errors associated with DFT. Hence, in this paper, we label compounds with a stability below 0.025 eV per atom (approximately kT at room temperature) as stable.

Structural distortions

After calculating all cubic perovskites, we investigated the effect of distortions on the stability of perovskites. To do so, we randomly selected one-third of the compositions (1,776) and computed their stability in the rhombohedral, tetragonal and orthorhombic distortion. We saw that distortions generally lower the energy of the ideal cubic structure but found no case where the distorted compound was lower in energy than the cubic phase by more than 0.5 eV per atom. Thus, we only calculated the distortion of compositions having a cubic stability lower than 0.5 eV per atom. This resulted in 2,162 (1,776+386) compositions where the four distortions (cubic rhombohedral, tetragonal and orthorhombic) where calculated.

Calculation of oxygen vacancy formation energy

Oxygen vacancy formation energies are calculated using a cubic undistorted A2B2O5 9-atom supercell and is given by

Where E(A2B2O5), E(ABO3) are the DFT total energies of the defect and pristine cell, respectively and μO is the chemical potential of oxygen. The choice of 9-atom supercell enables the high-throughput calculation of oxygen vacancy formation energy of all compounds.

Oxidation states and ionic size

Oxidation states for elements were computed using a bond valence method23. If a compound contains at least one element that does not have a BV parameter, the valence of that compound cannot be determined. With the oxidation numbers and coordination numbers (12, 6 and 2 for the A, B and O atoms, respectively) at hand, Shannon radii24,25 were used as a measure of the ionic size of every ion.

Experimental data on stable perovskites

To compare our stability predictions with experimental data, we collected data from the literature on experimentally known perovskites. Four review papers26–29 were aggregated and curated to identify 223 ABO3 perovskite compositions that have been experimentally synthesized. The curation was made by careful examination of source papers to ensure that the compounds were really synthesized and accurately characterized as a perovskite. In addition, compounds that were synthesized at high pressure (>1 GPa) were removed. We note that, for most of those compounds, the most stable distortion or oxidation states of the elements are not reported in the aggregated review papers.

Code availability

The automation of the high-throughput calculations and thermodynamic analysis were done using the qmpy python package available at (https://github.com/wolverton-research-group/qmpy) and is released under the MIT license. qmpy was also used to manage the high-throughput workflow and visualize the output from calculations. VASP, the DFT code used to generate the data in this work, is a proprietary software available at http://www.vasp.at.

Data Records

The list of 5,329 ABO3 perovskites can be found on figshare (Data Citation 1). All the calculations, along with all the 470,000 compounds used for the stability calculations are available for download or for direct consultation at www.oqmd.org. Kirklin et al.8 also contains detailed information about the calculation parameters.

File format

The data is stored in a CSV spreadsheet. Each row contains a different composition and each column is a property of that composition (described in Table 2). A calculation that did not converge to a final solution is indicated by a hyphen (‘−’) in the table for that composition. This lack of convergence can happen for variety of reasons, for instance an initial geometry that is very far from the final relaxed geometry, a chemistry consisting of elements for which electronic self-consistency is difficult to achieve, etc. These kinds of computational issues are commonplace in high-throughput methods where consistent settings have to be used for the calculation of all compounds in a reasonable amount of time.

Graphical representation of the data

The top part of Fig. 1 shows the number of stable perovskites as a function of the elements occurring on the A- and B-sites. Out of 73 elements, only boron does not appear in any stable perovskites. Lanthanides and alkaline earths are frequently on the A-site for stable perovskites whereas transition metals, specially the first row, are common on the B-site. These elemental preferences are consistent with what is experimentally reported in the literature1,26.

The bottom part of Fig. 1 shows the formation energy and band gap distribution for all the compounds calculated in this work. We see that most compounds have negative formation energies (only 276 are positive). The difference between negative formation energy and stability is apparent as the majority of materials have a negative formation energy but are not stable. As for the band gaps, the majority of them are 0 which is expected when using GGA-PBE (see band gap paragraph in the technical validation section).

Technical Validation

The open quantum materials database

The Open Quantum Materials Database uses density functional theory (DFT) to compute the total energies of every compound. DFT is widely used in solid states physics due to its accuracy and reproducibility30–32. In addition, previous studies have shown that formation energies calculated using DFT, when compared against those measured experimentally, have a similar accuracy as a comparison between experimental values from two different sources8.

Lattice parameter

For all the compounds that are predicted to be stable and have an entry in the ICSD, we compared the lattice parameters of the DFT relaxed structure with the lattice parameter of the experimental structure (Fig. 3). The mean error (ME), mean absolute error (MAE), mean relative error (MRE) and mean absolute relative error (MARE) across all lattice parameter for the 113 compounds are 0.011 Å, 0.048 Å, 0.20 and 0.82%, respectively. The magnitude and overestimation of the lattice parameters are consistent with other lattice parameters studies in the literature for DFT-PBE33.

(left) lattice parameter a, (center) lattice parameter b, and (right) lattice parameter c. In the top panels, the horizontal axes measure the difference between the computed and experimental lattice parameters while the vertical axes are the experimental lattice parameters. The lower plots correspond to a histogram of the difference in lattice parameters from DFT and experiment. The solid and dashed red lines indicate the average error, first and second standard deviations between DFT and experiment, respectively.

Supercell size for oxygen vacancy formation energy

We compared our oxygen vacancy formation energies calculated using 9-atom supercells with oxygen vacancy formation energy calculated using larger supercell sizes (79-atom)34. We see good agreement between our high-throughput approach and data from the literature (see Fig. 4). In addition, Curnan and Kitchin35 have showed that oxygen vacancy formation energy trend is largely unaffected by the supercell size for LaBO3 and SrBO3 (B=Sc-Cu).

Data for the 79-atom supercell are taken from Deml et al.34

Band gap

The band gaps were calculated with GGA-PBE, with U-values for some 3d-transition metals and actinides (see Table 1). GGA-PBE tends to underestimate the band gaps of semiconductors36,37 meaning that band gap values presented in this work have to be taken as lower bound and are useful to identify insulators. Different, much more expensive, calculations, such as hybrid functionals or quasiparticle calculations (G0W0, GW0 and GW), can be done to compute band gap values more accurately36.

Magnetism

Several perovskites are experimentally observed to have complex magnetic structures, e.g., antiferromagnetic order38. However, in order to save computational times as the magnetic ordering of an unknown structure cannot be known a priori, only ferromagnetic configurations are calculated in the present study. Stevanović et al.39 showed that the error associated with different magnetic ordering is of the order of 0.01 to 0.02 eV per atom by calculating ternary compounds with up to ten different spin orderings. To take this potential error into consideration, compounds with a hull distance below 0.025 eV per atom are labelled as stable in this study.

Comparison with experimentally observed perovskites

Of the 5,329 different compositions that were calculated, 395 are predicted to be thermodynamically stable by density functional theory. Out of those, 165 are reported in the literature. As a result, 230 new compounds are predicted to be DFT stable but not yet experimentally reported. This set of compounds represents a wide range of predictions amenable for materials synthesis.

The stability values of the 223 compounds that we found in 4 review papers26–29 are plotted in Fig. 5 (for clarity, all stable compounds are merged into the ‘0 hull distance bin’). The plot shows that a large number of these experimentally reported compounds are stable according to our DFT T=0 K calculations. However, the remainder of the phases are above the convex hull, and hence metastable (or unstable). The results of Fig. 5 shows the measure of metastability in terms of convex hull distance: there is rapid decay of the number of synthesized compounds as the convex hull distance increases, reaching almost 0 at a hull distance of 0.1 eV per atom. This 0.1 eV/atom metric for metastability is consistent with the results from another recent high-throughput study of metastabiity by Sun et al.40

Nine compounds reported in the literature are seen with a stability above 0.5 eV per atom. All these compounds contain rare earth elements, which are difficult to treat accurately with DFT because of the complexities associated with f-electron systems. In our high-throughput study, f-electrons are not included in the valence electrons of the pseudopotentials used, and therefore the DFT calculations of rare-earth-containing perovskites could have physical errors associated with the approximations made in the DFT calculations. For a more detailed discussion about f-electrons and frozen-core potentials, we refer the reader to Kirklin et al.8 Errors can also come from erroneous experimental characterization and/or classification.

Usage Notes

We suggest using the data as it is in the spreadsheet. If one chooses to access the data from OQMD via qmpy, we note that the OQMD is a constantly-growing database. Indeed, as a result of compounds being constantly calculated and added to the database, the stability of the already-present compounds can change: adding new stable compounds may change the predicted stability of a perovskite.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Emery, A. A. & Wolverton, C. High-throughput DFT calculations of formation energy, stability and oxygen vacancy formation energy of ABO3 perovskites. Sci. Data 4:170153 doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.153 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

References

Bhalla, A. S., Guo, R., Roy, R., Ruyan, A. S. B. & Rustum, G. The perovskite structure—a review of its role in ceramic science and technology. Mater. Res. Innov. 4, 3–26 (2000).

Chroneos, A., Vovk, R. V., Goulatis, I. & Goulatis, L. I. Oxygen transport in perovskite and related oxides: A brief review. J. Alloys Compd 494, 190–195 (2010).

Ishihara, T. . Perovskite Oxide for Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (Springer US, 2009). Available at http://www.springerlink.com/index/10.1007/978-0-387-77708-5.

Castelli, I. E. et al. New cubic perovskites for one- and two-photon water splitting using the computational materials repository. Energy Environ. Sci 5, 9034–9043 (2012).

Landis, D. D. et al. The Computational Materials Repository. Comput. Sci. Eng. 14, 51–57 (2012).

Kim, C., Pilania, G. & Ramprasad, R. Machine Learning Assisted Predictions of Intrinsic Dielectric Breakdown Strength of ABX3 Perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 14575–14580 (2016).

Castelli, I. E. & Jacobsen, K. W. Designing rules and probabilistic weighting for fast materials discovery in the Perovskite structure. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 22, 55007 (2014).

Kirklin, S. et al. The Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD): assessing the accuracy of DFT formation energies. npj Comput. Mater 1, 15010 (2015).

Bergerhoff, G., Hundt, R., Sievers, R. & Brown, I. D. The inorganic crystal structure data base. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 23, 66–69 (1983).

Belsky, A., Hellenbrandt, M., Karen, V. L. & Luksch, P. New developments in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD): accessibility in support of materials research and design. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci 58, 364–369 (2002).

Emery, A. A., Saal, J. E., Kirklin, S., Hegde, V. I. & Wolverton, C. High-Throughput Computational Screening of Perovskites for Thermochemical Water Splitting Applications. Chem. Mater. 28, 5621–5634 (2016).

Lookman, T., Alexander, F. J. & Bishop, A. R. Perspective: Codesign for materials science: An optimal learning approach. APL Mater 4, 053501 (2016).

Agrawal, A. & Choudhary, A. Perspective: Materials informatics and big data: Realization of the ‘fourth paradigm’ of science in materials science. APL Mater 4, 53208 (2016).

Rajan, K. Materials Informatics: The Materials ‘ Gene ’ and Big Data. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res 45, 153–169 (2015).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Dudarev, S. L., Botton, G. A., Savrasov, S. Y., Humphreys, C. J. & Sutton, A. P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505–1509 (1998).

Wang, L., Maxisch, T. & Ceder, G. Oxidation energies of transition metal oxides within the GGA+U framework. Phys. Rev. B 73, 195107 (2006).

Barber, C. B., Dobkin, D. P. & Huhdanpaa, H. The quickhull algorithm for convex hulls. ACM Trans. Math. Softw 22, 469–483 (1996).

Akbarzadeh, A. R., Ozolins, V. & Wolverton, C. First-Principles Determination of Multicomponent Hydride Phase Diagrams: Application to the Li-Mg-N-H System. Adv. Mater. 19, 3233–3239 (2007).

O’Keefe, M. & Brese, N. E. Atom sizes and bond lengths in molecules and crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, 3226–3229 (1991).

Shannon, R. D. & Prewitt, C. T. Effective ionic radii in oxides and fluorides. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem 25, 925–946 (1969).

Shannon, R. D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 32, 751–767 (1976).

Roth, R. S. Classification of perovskite and other ABO3-type compounds. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. (1934) 58, 75–88 (1957).

Giaquinta, D. M. & zur Loye, H.-C. Structural Predictions in the ABO3 Phase Diagram. Chem. Mater. 6, 365–372 (1994).

Li, C., Soh, K. C. K. & Wu, P. Formability of ABO3 perovskites. J. Alloys Compd 372, 40–48 (2004).

Zhang, H., Li, N., Li, K. & Xue, D. Structural stability and formability of ABO3 -type perovskite compounds. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci 63, 812–818 (2007).

Lejaeghere, K. et al. Reproducibility in density functional theory calculations of solids. Science (80−.) 351, aad3000 (2016).

Curtarolo, S., Morgan, D. & Ceder, G. Accuracy of ab initio methods in predicting the crystal structures of metals: A review of 80 binary alloys. Calphad Comput. Coupling Phase Diagrams Thermochem 29, 163–211 (2005).

Hautier, G., Ong, S. P., Jain, A., Moore, C. J. & Ceder, G. Accuracy of density functional theory in predicting formation energies of ternary oxides from binary oxides and its implication on phase stability. Phys. Rev. B 85, 155208 (2012).

Haas, P., Tran, F. & Blaha, P. Calculation of the lattice constant of solids with semilocal functionals. Phys. Rev. B—Condens. Matter Mater. Phys 79, 1–10 (2009).

Deml, A. M. et al. Tunable Oxygen Vacancy Formation Energetics in the Complex Perovskite Oxide Srx La1- x Mny Al1- y O3. Chem. Mater. 26, 6595–6602 (2014).

Curnan, M. T. & Kitchin, J. R. Effects of Concentration, Crystal Structure, Magnetism, and Electronic Structure Method on First-Principles Oxygen Vacancy Formation Energy Trends in Perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 28776–28790 (2014).

Shishkin, M. & Kresse, G. Self-consistent GW calculations for semiconductors and insulators. Phys. Rev. B 75, 235102 (2007).

Perdew, J. P. Density functional theory and the band gap problem. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 30, 451–451 (1986).

Lee, Y.-L., Kleis, J., Rossmeisl, J. & Morgan, D. Ab initio energetics of LaBO3 (001) (B=Mn, Fe, Co, and Ni) for solid oxide fuel cell cathodes. Phys. Rev. B 80, 224101 (2009).

Stevanović, V., Lany, S., Zhang, X. & Zunger, A. Correcting density functional theory for accurate predictions of compound enthalpies of formation: Fitted elemental-phase reference energies. Phys. Rev. B 85, 115104 (2012).

Sun, W. et al. The Thermodynamic Scale of Inorganic Crystalline Metastability. Sci. Adv 2, e1600225 (2016).

Data Citations

Emery, A. A., & Wolverton, C. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.5334142 (2017)

Acknowledgements

This work was also funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences under Grant DE-FG02-07ER46433. This research used computational resources provided by the Quest high-performance computing facility at Northwestern University which is jointly supported by the Office of the Provost, the Office for Research, and Northwestern University Information Technology as well as the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, a DOE Office of Science User Facility supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.E. ran the calculations and analyzed the data. C.W. conceived the overall research plan, provided advice for the work, and helped analyze the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

ISA-Tab metadata

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ applies to the metadata files made available in this article.

About this article

Cite this article

Emery, A., Wolverton, C. High-throughput DFT calculations of formation energy, stability and oxygen vacancy formation energy of ABO3 perovskites. Sci Data 4, 170153 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.153

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.153

This article is cited by

-

Material Property Prediction Using Graphs Based on Generically Complete Isometry Invariants

Integrating Materials and Manufacturing Innovation (2024)

-

A DFT Study of Bandgap Engineering and Tuning of Structural, Electronic, Optical, Mechanical and Transport Properties of Novel [Ba4Sb4Se11]: Sr3+ Selenoantimonate for Optoelectronic and Energy Exploitations

Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials (2024)

-

Methods and applications of machine learning in computational design of optoelectronic semiconductors

Science China Materials (2024)

-

Unveiling oxygen vacancy impact on lizardite thermo and mechanical properties

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Prediction of Van Hove singularity systems in ternary borides

npj Computational Materials (2023)